3,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Sandstone Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

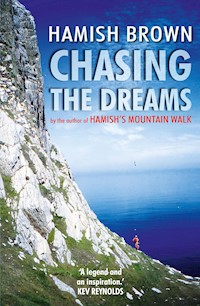

Hamish Brown, who occupies a special place as a Scottish writer and traveller, turns his wealth of experience into captivating narratives of fascinating people and places; sometimes serious, at times laugh aloud in this new volume. Chasing the Dreams is a companion to Walking the Song, with the same kaleidoscopic range and variety, telling of treks in Scotland, the Alps, Atlas and Himalaya, of ventures by canoe and sailing, ski-ing and cycling.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Hamish Brown has wandered the world and its mountains all his life. His early Hamish’s Mountain Walk is a classic, the story of the first continuous round of the Munros, but he has written extensively about Scotland, the Lowland canals, a trio walking the West Highland Way, and guides to the Fife Coast, Skye and Kintail. Besides editing the writings of Seton Gordon and Tom Weir, he has compiled the poetry anthologies Speak to the Hills and Poems of the Scottish Hills. The Mountains look on Marrakech (an end-to-end traverse of the Atlas) was short-listed for the Boardman-Tasker Prize for mountain literature. He has already published Walking the Song, another collection of travel writing over the years, to which Chasing the Dreams is a companion volume. His most recent book East of West, West of East tells of his family’s travels and escaping Malaya and Singapore in World War Two – a remarkable story based on Hamish’s mother’s letters, his own boyhood memories, and his father’s terse report of the horrors of escaping the Japanese advance.

In recognition of his services to literature, Hamish received an honorary D.Litt. from St Andrews University in 1997 and a D.Univ. from the Open University in 2007. He was made an MBE in 2001 and received the Scottish Award for Excellence in Mountain Culture in 2017.

Recent titles by Hamish Brown

Walking the Song

(writings from over the years)

East of West, West of East

(the family saga of escaping the Japanese in World War Two)

As editor: Tom Weir, an anthology

(a selection of published and unpublished writing:illustrated)

The Oldest Post Office in the World and Other Scottish Oddities

(over ninety extraordinary places described and illustrated)

The Mountains Look on Marrakech

(the story of a 1000 mile, 96 day traverse of the Atlas)

The Atlas Mountains

(superbly illustrated descriptions of the best treks and climbs)

Three Men on the Way Way

(the experiences of three Fifers walking the West Highland Way)

Canals Across Scotland

(everything about the Union and Forth & Clyde Canals; lavishly illustrated)

Republished, with new introductions and illustrations

Hamish’s Mountain Walk

(the first non-stop round of the Munros; a classic)

Hamish’s Groats End Walk

(covers the English, Welsh and Irish 3,000ers)

Climbing the Corbetts

(narrative of these mountains)

Published in Great Britain by

Sandstone Press Ltd

Suite One, Willow House

Stoneyfield Business Park

Inverness

IV2 7PA

Scotland

www.sandstonepress.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored

or transmitted in any form without the express written

permission of the publisher.

Copyright © Hamish Brown 2019

The moral right of Hamish Brown to be recognised as the

author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the

Copyright, Design and Patent Act, 1988.

The publisher acknowledges support from Creative Scotland

towards publication of this volume.

ISBN: 978-1-912240-78-4

ISBNe: 978-1-912240-79-1

Your young men shall see visions and your old men shall dream dreams.

Acts 2:17

Dreams are more potent than reason.

CONTENTS

Foreword

Tramping in Scotland

The First Munro on Ski

Easter: Mull Aflame

Across Sutherland and Caithness

With Boots to the Maiden

A Salting of Snow

By Any Method

The Great Glen by Canoe

A Sea Route to the Hills

Cycling the Four

The Ring of Tarf

Last Run, Coire na Ciste

Of Other Days

To Knoydart with Billy

The Ben Nevis Observatory

Crossing the Cairngorms, 1892

A Cuillin Pioneer

Wade and Caulfeild

Disturbing Hinds

Youthful Escapades

– The School –

Tackling the Cuillin

The Wild West of Jura

Snowed in at Glendoll

A Night Out on Beinn a’Bhuird

Along the Lines

No Choice

Further Afield

Misguided Sometimes

The Valley of a Thousand Hills

Return to Kilimanjaro

The Rishi Ganga

A Dream of Jerusalem

The Atlas Allure

– The Mountains –

To Ride a Log

The Glittering Summit

Happiness is a Hammam

Lalla Ariba!

Hell on Earth

Remembered Moments

Nomads Passing

Ragbag

The 1978 Blizzard

What’s in a Name

The Calendar Round

Too Dull a River

Taliban among the Trees

My Last Bivouac

Night Train

Just So; Stories

– About the Stories –

Sgurr Thuilm

Bothy Nights at Shenavall

Schiehallion

The Frog Prince of Lochnagar

Counting Sheep

Acknowledgements

FOREWORD

A previous collection, Walking the Song, I called a potpourri, a collection mainly of articles which had appeared in print over the length of an active life. Chasing the Dreams is very much in the same vein, describing more places and experiences that caught my imagination and have stayed clear in my ‘shaky edifice of memory’. Most mountaineers are curious about life in general, with many strands to the rope that belays them to the world. Pieces selected have largely been left as they appeared though I have added a few notes where helpful. Sections this time end with a poem, and the last section is different. Fortunately, I have always kept logs (diaries) so can check on facts but I just wish I’d taken more to heart Dr Johnson’s admonition to Boswell, ‘... when we travel again let us look better about us.’

As with Song, Dreams is set out in sections of related themes and interests, topical and geographical. There is considerable autobiographical content as, perforce, I’m describing the curious I’ve seen, enjoyed, or suffered. In my experience, the fabled city of dreams is always over the horizon, never just round the corner. Dreams have to be chased. It is the chasing that is life. As Robert Service sang, ‘... it isn’t the gold that I’m wanting, / So much as just finding the gold’.

In the longer Scottish-based accounts the Ordnance Survey Landranger map number is given at the start so, if wanted, readers can follow wanderings in detail; and I’ve a sketch map for one Atlas narrative. Heights and distances set a problem because of our half-baked attempt at going metric but generally British locations will have heights in either feet or metres and distances in miles while furth of Britain is all metric.

If there is less ‘straight’ mountaineering content in Dreams this is largely from responses to Song where many said it was the stories of people and places and various ‘happenings’ which were most interesting. (‘One climb described is very like any other climb described.’) There’s a touch of the nostalgic, remembering a more innocent world, a less-endangered, unpressurised existence and I was also fortunate in seeing many of the world’s great sites / sights (Victoria Falls, Taj Mahal, Machu Picchu) before the advent of Tourism, with a capital T. Tourism always wears such big boots. We have become an affluent society, in thrall to such trite interests, while our needy seas and landscapes face a general insensitivity, and the continuing rapacity of commercial interests. Two of my first realisations of this when younger were the unbelievable plan to dam the Nevis gorge to make more electricity (which roused Tom Weir to the conservation battle of his life) and the National Trust for Scotland surrendering St Kilda – now a double World Heritage Site – to the military. Today’s most blatant scam is seeing vast tracks of scenic landscape blighted with windfarms in so many, many wrong places.

All through my lifetime this duck-nibbling destruction of landscape quality has gone on; constant rear-guard actions no match for the big guns of moneyed self-interests. We know we need the rainforests yet continue to destroy them, we need the oceans but continue to misuse them, we are even filling the sky overhead with junk. What right have we to seek other worlds when we have miscarried on the one we have? Thirty years ago I suggested we were ‘a failed species on the way out’. Maybe the world will flourish again when we have gone.

At school I was once called ‘Curiosity Kid’ (one regular, much-enjoyed schools’ ‘Nature Question Time’ programme on the ‘wireless’ was entirely given over to answering the questions I’d sent in) and I am glad never to have lost an interest in this very fascinating and very beautiful world, however we, humankind, seek to destroy it and each other. I’ve walked songs and chased dreams. Norman McCaig wrote ‘There’s a Schiehallion wherever you go, / the thing is, to climb it.’ Dreams have to be chased. Beware, however, once you have the sniff of desert, mountain or sea air, you may be sneezing for the rest of your life.

Chasing the Dreams is the result of being fortunate enough to spend most of a lifetime roaming wilder places (mostly mountains), at home in Scotland and many far corners of the world, from Arctic to Mediterranean ranges, America, Africa and the East. Fortuitously, thirteen years, which is the total from fifty-three visits, have been to the Berber people’s world of the Atlas Mountains. There is something, beyond telling, in having another place in the world, another people and culture nobler than one’s own in which to find solace and escape the inconsequential pressures and hamster-wheel captivity of life in our Western world. It is desirable to have a well-filled past; it is all the future we eventually have to hold.

Happy the man, and happy he alone, He who can call today his own, He who, secure within, can say, Tomorrow, do thy worst for I have lived today.

John Dryden

TRAMPING IN SCOTLAND

The First Munro on Ski

I find exercise . . .unbearable. I much prefer to set off and suffer the first few weeks.

Wally Herbert

This piece was written over fifty years ago and I came on it only recently – and marvelled at my youthful enthusiasm. That first Munro, Stuc a’Chroin, was climbed with ordinary ski equipment: no touring bindings with heel uplift, no skins, nothing to help. There is nothing quite like ‘the first fine careless rapture’ of confident youth so I have left the text unaltered. A note of warning however: our teaching ourselves to ski was not a good idea. There are technical tricks we never discovered, and we picked up some bad habits. When I realised this I went on a course at Glenmore Lodge to be ‘sorted out’ (by instructor Clive Freshwater who would later open the Loch Insh Outdoor Centre). I would go on to gain my ski instructor’s certificate and enjoy ski-mountaineering in the Pyrenees, Alps and Atlas. So, if you’d like to learn to ski, do so under proper instructors!

Another matter that this piece, never intended for publication, almost flaunts, is the abundant availability of snow. Our recalling good snowy winters those decades ago is not just the gilding of memory – they happened. I kept a note of hills climbed on Christmas Day and New Year’s Day and they invariably tell of deep snow flounders in the far North West, of lochs frozen solid, of lower landscapes and roads burdened with snow. Once competent enough on skis I determined that skiing was the only way to ‘bag’ winter Munros. But after some years the number of such outings began to drop, for starting points became higher and higher as the snow base rose, and it became far too big a hassle to gain a reward. Struggling up through the heather carrying skis was not in the contract. Oh, but what glory days they were! When it was good it was purest bliss, as I tell in ‘The Ring of Tarf’ a little further on. You need to be mental to trump any denial of climate change by now.

From extensive reading at this time I knew of mountain skiing in the Alps or in Polar regions, but what about in Scotland? After a deep snow flounder over a summit above Drumochter I came on the sweeping curves of ski tracks on the slopes below me. Ah! – it was done in Scotland. Skiing could complete an enthusiast’s winter triptych: Munros, Climbing, Skiing.

A harsh winter promptly brought snow down to sea level in Fife (February 1963) and, after a first morning on a local golf course, we lugged our skis up Largo Law (just under 1000 feet). Icy, crusted conditions ensured plenty of thrills and spills, and a dramatic encounter with the top wires of a fence when heading down and suddenly realising that skis did not have brakes. We had a few encounters of a prickly kind when ending up in gorse bushes. Fit climbers as we thought ourselves, we suffered aches and pains and stiffness on a new level after that.

Our next outing was to the Ochils, where we camped at Paradise above Dollar, on a level with Castle Campbell. On good slopes there we learned kick-turns then, in the afternoon, headed up the 2000 foot White Wisp in conditions all too familiar to tourers: spindrift blasting across the snow and stinging our faces when we cowered in the stronger hits. On the bald summit we crouched for long minutes, gasping and blinded, stunned by the brutal assault of the storm. We edged down the lip of the corrie for shelter and noted the length of the burn below was choked with avalanche debris. Over half a mile of circling windslab snow had been detached; as we skied along we trembled at the possibility of setting off another lot. Vanishing in and out of clouds, we again zigzagged down and round the hill. This first taste of the heights was good, we felt, but being able to turn properly would be an asset. Kick-turns as our only option had limitations, and were apt to become sit-down turns on steeper, deeper snow.

We had another brilliant day just along from Buckhaven, the perfect powder snow lying six inches deep on the braes. We actually managed turns – of a sort. When we made a whole series down to the beach there was a glow of satisfaction. I recalled entries in Alpine hut books that told of exploits like Chamonix to Zermatt. Someday perhaps . . . Meanwhile, we’d had Largo Law, just under 1,000 feet, Whitewisp, just over 2,000 feet. Surely the next step was a Munro on skis.

In the meantime two of my pupils, together, and I, alone, set off to hitch north on a Friday for a rendezvous on the edge of Rannoch Moor. We had our eyes on a climb on Saturday, and on Sunday, when our local club’s hired bus arrived, we planned the historic Upper Couloir of Stob Ghabhar.

None of us managed further than Strathyre. I perforce spent a tentless night out in the forest near the village: an unforgettable bivouac, so still a night that a candle on a spruce frond lit up the scene in magical fashion. On a li-lo, and with two skimpy summer sleeping bags, I was cosy enough and lay reading awhile. (Somehow, to my embarrassment, the Sunday Post got hold of this incident and made a song and dance about it.)

In the morning, with no opening of roads ahead, I thumbed a lift southwards – all the way to Edinburgh in one go – and returned to Fife by train. A phone call confirmed that the Kirkcaldy Mountaineering Club bus would still set off on the Sunday and would simply stop when forced to and let us loose wherever. I could take my skis, I decided. (Later I heard the two lads supposedly meeting up with me the day before had spent the weekend camping and roaming the Ochils.)

The bus stuck at Lochearnhead; Glen Ogle was still blocked. A mass assault on the Ben Vorlich/Stuc a’Chroin pair was mooted and so, by chance, here was the opportunity for my first Munro on skis.

What climber does not revel in rhythm? Here it was then: on and on up Glenample, across the burn, gradually ascending and traversing the hillside. Only occasionally was a turn necessary, only occasionally a herring-bone pattern to break the long clean line. Hard work, but joyous, satisfying. Above Glenample shieling I heard the dogs barking and saw the dots of our bus group crossing to the cottages far below. Who had the laugh now? (Most regarded skis as very suspect).

The Allt a’Choire Fhuadaraich was crossed and for the steep climb up Creag Dubh (the Black Crag) I dismounted – and at once sank in to the knees. Those 500 feet are best forgotten. I had to rest continually with heart pounding furiously. Gradually I reached the stage of cursing skis and climbing and myself for ever putting on a pair of boots. On top of the shoulder I lay on some bare rocks with legs shaking uncontrollably and the sweat freezing my shirt tail into a board. I lay flat out, crunching sugary sweets until muscles and nerves slowly returned to normal. The others could catch up if they liked. To hell with it!

Skis on again for the continuing ascent. Several times I had to rest, twice I tried to walk only to find it even more strenuous. Gradually the height was gained, and spirits could do nothing but follow as Ben More and Stobinian rose over the intervening hills as great white pyramids.

The view from the hard-won summit was superlative: Lowlands and Highlands completely white-washed. I sat by the cairn eating and staring round, naming off range after range of peaks from Arran to Nevis to the Cairngorms – they were all there – all old friends, all climbed, and loved and longed for again. The Stuc had always been kind: this was the fifth perfect stay on its top in two years. I dozed off for half an hour until the cold woke me again. I fastened on the bindings and pushed off – and went flat on my back. Ice!

I felt a mixture of meanness and wickedness in a satisfying sort of way as I sped across Coire Chroisg to where the others were still plodding up. After a brief exchange I swung away across the corrie again – back and forwards – long runs and sweeping turns, all with exaggerated aplomb. Some turns were not exactly smooth but I managed not to fall and spoil it all. With the others on the top ridge I swung along to Creag Dubh again. Here the slope was steep and broken by crags and frozen waterfalls and burns. Its descent was highly exciting. At the foot, long slopes of soft snow gave endless swinging routes. The air rushed past with a roaring and popping in the ears. Rather frightening. Very wonderful. Then into the banked hollow of the burn: a mild Cresta run to twist and turn down for a mile. When it became too hectic it was simple to turn up the bank and lose momentum.

About the 1,500 ft contour I skirted round under Creagan nan Gabhar and the aim was changed to losing as little height as possible while running down Glenample. Apart from the crossing of the farm burns it was a continuous glide of one-and-a-half miles. In front lay Loch Earn and the creamy hills of Glen Ogle, behind the unwavering track from the crags and the white ridges lifting against an Alpine-blue sky: utter silence but for the soft swish of the skis; utter content; singing solitude; tired muscles relaxing. Yes, every agony was worthwhile. I laughed and sang and then turned for a last schuss down into the trees and over the burn for the path again. Lingering pauses were made beside snow-ringed pools. Only a solitary hare moved in the warm afternoon hush. I walked back to the bus in a dream. Tomorrow the agony!

Three hours later the others came back. Till then I sat in the hotel enjoying cup after cup of hot, sweet tea. The armchair was soft and relaxing. The view was across to the hills we had been on. Slowly they turned pink and the shadows rose with dusk over their slopes. The first star shone out above a lemon-washed crest. As Ben Johnson noted, ‘… in short measure life may perfect be.’

Easter: Mull Aflame

Of course there are dragons in the mountains. That is their attraction and their fear.

OSLR 48, 49

‘Where do you want off?’ the driver asked as we sped down Glen More in the Iona Ferry bus from Craignure. ‘At the bridge, please’ – but I should have said ‘right now,’ for framed in the glen was the bold, angular bulk of Ben More of Mull, sovereign Munro in all the isles – other than extravagant Skye. The hill lay sharp as if chiselled, a blaze of blue beyond; a picture of perfection.

We were dropped off at the Teanga Brideag bridge, after a wee chat, for on Mull bus drivers are friendly. He said the weather might last, even if Mull had ‘used up half the annual good days this one week.’ The bus had picked us up in eastern Glen More where we had left my campervan for our exit from the hills once Mull had given Colin his first Munro and I had climbed my penultimate Corbett. There had been frost on the van’s windscreen when we left Fishnish at 07.30. We left a note with the Craignure police in case someone began to worry about the van, parked for several days.

As the bus sped off for Loch Sgridain and the Ross of Mull to the Iona ferry, we were panting up the Brideag Burn, thankful to be going over only the first bosses of hill to pitch our camp near where I had first camped on the island a score of years before. That, too, had been during an Easter heatwave, with a school group, while now the sun smote down on a sturdy, fit young nephew, enthusiastic for any ploy on land or sea. The heat was tempered by mercy, however, as, despite the sun, a bitter wind blew. For walking this was an unusual perfection: no rain, no midges, no sweat. Storm, the dog, may have wished for a shorter coat; he was a Shetland Collie.

The slopes were deep-littered in tawny dry grass which we collected in armfuls to lay under our tent groundsheets. Boulders from the burn provided stools. We brewed, and with the tea we ate the last of a Christmas cake. Migrant wheatears flew past the site. A first wood anemone was in flower in a rocky nook above a deep pool of startling clarity.

I recounted to Colin how, on that first visit, everyone dived and splashed in the water and then wandered slowly upstream from tempting pool to delectable waterfall to better pool. My snooze by the tents had been broken an hour or two later by shouts and yells as down the hillside came what looked like a gang of naked savages. The slopes were just sprouting new growth after extensive burning and proved very sharp to bare feet, hence the war dances. They were also sending up clouds of black soot – a good excuse for another swim.

On that visit we also had an unforgettable close encounter of a midgy kind. The sweltering day had brought them to the boil and, as we were dependent on public transport and were camping, flight was impossible. We camped on a breezy knoll above the burn, saved largely by anabatic and katabatic winds. The cleft with the burn, entirely windless, held a seething stew of midges. One could reach an arm into the buzz and in seconds it would be covered in a black tactile skin of insects. Draw the arm out again and they fell off like blowing coal dust. It was a shivery fascination to do this, for at the back of one’s mind was the vision of doom if the kindly breezes should go. On that visit, however, the breezes sent for reinforcements, and a gale drove us to Tobermory youth hostel, a cosy eighteenth-century building on the seafront. At the storm’s climax we went to Calgary Bay to see immense rollers smashing ashore, spray flying inland for hundreds of yards, and the waterfalls standing on end. Today’s ascent with Colin would be quite different. We set off at 11.00 – the last time I checked my watch. When there’s plenty time, forget time.

Ben More is a big tent-shaped block from many angles, with the lower cone of A’Chioch lying to the east along a narrow ridge. The hill often appears to be smoking like a volcano (which it once was) or looks black and forbidding, for the rock is mainly basalt, rising from great skirts of scree. Not to be underestimated: Loch na Keal or Loch Scridain, the usual starting points, are sea lochs, so you climb all of Ben More’s 3,169 ft (966 m). The hard work is rewarded by hauling out to as fine a hill view as you’ll enjoy in Britain, ranging from Ireland in the south to the Torridons in the north, and with the Outer Hebrides down the western horizon. Cuillin, Rum, Ardgour, Nevis, Etive, Cruachan, Arran, Jura, all these and other mainland or island hills will be displayed on the days of gifted glory.

Ben More is the top favourite of all Munros that are kept for ‘the last’ by those who have been ticking off the list. The next favourite is the Inaccessible Pinnacle – perhaps from being ‘the hardest Munro’ – but Ben More is kept for the last for geographical reasons and, I’m sure, a touch of the romantic. Being on an island does mean a certain amount of extra organisation is required to reach Mull, so Ben More is often only given consideration well on in a walker’s Munroing, at which stage the thought is planted ‘This would be a splendid Munro to finish on’. Oddly, it was my first Munro when I set off to do all the Munros in a single expedition. That was a heatwave April as well, with the girls in bikinis – and regretting it by the time we got back to our camp by Loch Scridain. They were all too literally ‘in the pink’ by then.

I have just checked my record for weather in case I’m also conveying the idea that the weather in Mull is always sunny. I find notes of ascents with ‘traverse in thick mist,’ ‘severe gales,’ ‘thick, wet clag,’ so the weather is fairly average. But when it is good, it is very, very good.

Colin and I cut the corner a bit before the head of the valley as we wanted to follow up a side-stream descending from the pap of A’Chioch – water would be welcome up high with such thirsty walking. Hills began rising all around. Mull is surprisingly hilly and feels big enough that you can forget you are on an island.

I’m sure the majority of the people who climb Ben More simply walk up the NW slope from Dhiseig (Dhisig), a pity for the finest approach is undoubtedly along the eastern ridge from A’Chioch. I’d recommend our line from Glen More, or by Glen Clachaig from Loch Ba to the north-east. A’Chioch is a cone of ‘chaotic rubbish’ to quote one of my lads, but any contouring traverse to avoid the bump gives much harder work. Colin romped up its unstable slopes. Once on the connecting ridge to Ben More the going becomes ‘interesting’. We followed a white hare to begin with, Storm tracking it along the edge of nothing in a way we found rather nerve-wracking, on a sort of Carn Mor Dearg Arête type of ridge. Ben More’s steep north face was still deeply snow covered, scarred with fallen cornices, and the rocks crowning it were grey-bearded with overnight frost. By this approach Ben More feels like a real mountain.

Approaching the top, we could hear voices above us and Storm shot off to bark insults at the summit trespassers. For a ‘remoter’ Munro, Ben More was remarkably busy. A couple from Derbyshire and a lad from Edinburgh exchanged greetings and exclamations of delight. Storm rolled on the snow. Never a demonstrative lad, Colin just grinned, and dug out an Easter egg saved for the occasion of topping his first Munro. I wonder whether he could have any idea that he would later come to live and work out here in the West. In 2004, as part of the Boots Across Scotland event (described in a later section), he climbed Ben More again as his chosen hill. We stayed on the sunny summit for half an hour. By then, another man and dog and a cheery Croydon school party had arrived. A swirl of seagulls was speculating about our being a food source.

Those who have kept Ben More for their last Munro will be delighted at the choice if they enjoy such a fine day as we did; but they may not know of a bad-weather hazard shared with the Skye Munros: the summit rocks are magnetic and the compass erratic. This is quite amusing (or quite alarming) for we are so brainwashed into believing ‘the compass never lies’ that we are shocked when it does. A careful bearing off the summit of Ben More will take you down on a quite unscheduled line! The effect is bad only on the summit. Knowing this in advance, one just takes care: there are well-defined ridges and corrie edges which help with navigation. A trick I learnt for Skye conditions was to make tiny two-pebble cairns up the last clouded climb – so the way off was well-indicated, while the markers were easily enough kicked over in passing during the descent.

We scampered off, down to the A’Chioch col again, then turned down into Coir’ Odhar and across to follow ridge rather than valley back to the tents. We managed to stalk five hinds to about fifty yards, and shortly afterwards Storm set up two hares which careered off to panic another group of hinds. For a while the whole hillside seemed to be moving.

We came upon some big whalebacks of rough granite, but they were too easy-angled to be of scrambling interest. The basalt is useless, too, and the red granite outcrops of Fionnphort are too small, so Mull is not much of a rock-climber’s island. We arrived back at the tents ready for a brew and all too soon the shadows crept down. I kept moving up the hillside with my book to stay in the sun, while Colin started cooking, another fun part of the outdoor world he was into. The day grew bitterly cold, and after supper we soon burrowed into our sleeping bags, enjoying ‘the rush of the burn and hill bliss’ as my log noted.

Mull offers excellent trekking routes and the next day we had a good sample. We were heading for a bothy, so as we’d be motoring this way at the end of our sortie, we stashed the tents and other odds and ends beside the next burn up Glen More, hiding them with the plentiful dry grass. This Allt Ghillecaluim came down in many little falls and the old path up its banks was visible only occasionally as we sweated up Coir’ a’Mhaim (many old paths in Mull are no longer maintained). There was a long levelling-out with the burn slowly shrinking till it vanished and we emerged on to the fine col of Mam Breapadail (c.1,250 ft, 380 m) with its whisper of wind and sky-scraper cumulus above.

This was no gentle watershed crossing: the ground fell away before us into Coire Mor with Devil’s Beef Tub steepness and Glen Cannel seemed miles below, yet we soon zigzagged down to brew where several streams joined, each draining an equally fine corrie, an impressive heart to the mountains of Mull at the head of the flat-floored Glen Cannel. A purply haze crept over the ridges and only when we smelled it did we recognise it as moor-burning. The shepherds were busy using the dry spell.

A mile down the glen was a ruined farm, Gortenbuie, while across the valley lay long-abandoned burial grounds – the ‘dead centre of Mull’ Colin reckoned. There were no graves visible. People no longer live in these remote spots; the shepherds come in by Land Rover and return to comfy homes on the coast at night. The gain is sometimes ours as we acquire a bothy here and there. We headed off for one now, crossing the burn by the skeletal beams of a 1910 bridge.

On the way we passed a ‘bird-cone’ which had been much used by a buzzard (we’d put one up), for it was well whitewashed and surrounded by animal skulls, vertebrae, fluff and feathers. These cones seem to be a phenomenon peculiar to the islands. Usually they are coastal, but here they were central and in profusion. A slight knoll makes a perch, the birds’ droppings encourage growth, dust is caught by the growth and the process builds up a solid green cone. On Jura I have seen them five feet high.

We cut up and round, eastwards and then northwards, with birch wood [now, alas, a conifer plantation – Glen Forsa, too is now constipated with conifers from end to end] leading to a pass at just over 500 ft (151 m) and then down to neat Tomsleibhe bothy, where a squabble of crows rather grudgingly welcomed us. Glen Forsa was busy with men and dogs driving sheep out of danger, so after a lunchtime brew Colin, Storm and I headed south up Glen Lean behind the bothy for Beinn Talaidh (Talla). Some dead sheep lay in the burn: ‘Never mind, Colin; just extra protein’. We more or less kept to the stream itself – ‘burning up’ as I called it – till near the top the burn ran in a small gorge which might offer us some scrambling. Back, nearly at valley level, we had found some aluminium rods which I hoped might be parts of a meteorological balloon, but after finding some other bits and pieces we realised there had been a plane crash somewhere nearby. The pieces of wreckage became steadily more numerous as we boulder-hopped up the burn, with bits of complicated machinery appearing as well as mangled shards of the aircraft’s skin. A big strut lay on the bank. Then ahead we saw a pile of grey material, as if a lorry had tipped a load of rubbish into the gorge. The crash site was above, high on the hill, so the wreckage must have been pushed down into the gorge. There must have been mice living in the wreckage, for Storm was soon all but invisible – just his tail waving from a jagged hole. There was a propeller showing and one big and one small wheel. Colin thought we were seeing two engines, but it was all so broken up it was difficult to recognise anything. He found one ‘sliding part’ of stainless steel that glittered with surprising freshness, but much of the wreckage was thoroughly embedded in the rocky banks. What we saw was sickening, not just an impersonal TV report; this was real.

We climbed on in silence, but the gully walls had converged to a narrow gut down which shot the small but wetting stream. The escape was an ungardened Jericho Wall, and we scrambled up a loose-enough exit line, which certainly took our minds off the crashed aircraft. Storm rushed off and was soon tail flag-waving in another hole. It looked like a rabbit burrow, but this was 1,700 ft up and all we saw were hares in various stages of transition from winter to summer colouring. There are either high-level rabbits on Mull, or hares that burrow.

The east flank of Talaidh is steep with plenty of rock poking through so any distraction was welcome as we zigzagged on. Eventually we came up against the summit screes, but just as we were about to tackle them I noted a faint track going off at a slant to the right. Whether it was made by man, sheep or deer we did not debate. We used it thankfully, crossed a rim of snow, and were soon scurrying, Colin ahead, along the easy-angled final shaly stretch to the cylindrical concrete trig pillar of Beinn Talaidh. I’d ticked my Corbett [now, alas, reclassified as a Graham, only just failing to make 2,500 feet].

The glory had departed: steely greys and denim blues filled in the picture, like a poster done by a child with a limited range of felt-tip pens. As a viewpoint, Talaidh matched Ben More (‘stunning’ in the SMC guide). This is very often true of many Corbetts and lesser summits. They may not be so high, but often being more isolated, they can provide grandstand views. Indeed, Beinn Talaidh is possibly Gaelic for hill of the view.

Dun da Ghaoithe, Mull’s undisputed Corbett at 2,513 ft (766 m), stands across Glen Forsa in the eastern block of hills. This hill, fort of two winds, can be climbed in a pleasant circuit from Craignure or by taking the Iona bus round to Glen More and returning over the Corbett. I pointed out several other challenging hills south of the Glen More road, such as Ben Buie (one of my favourites), while perhaps as rewarding as any ascent, the coastal paths give a rich variety of walks. In some ways one wants a canoe or a boat for Mull as well. One of my friends actually kept Ben More as his last Munro simply so he could sail to the island for the celebratory completing.

For this Easter visit we had hired a caravan near Fishnish and Colin’s gran, my mother, was ensconced there during our sortie in the hills. (Travelling to and from Mull she had slept in the campervan while we two slept in tents.) After our return to Fishnish we all went to explore Duart Castle, walk the Carsaig coast, voyage out on the Iolaire from Fhionnphort to Staffa for Fingal’s Cave, and visit Mull’s Little Theatre for a reading of poems and prose plus a Chekhov skit; activities enjoyed alike by Colin, a busy 12-year-old, and mother, a lively 79.

For two or three years a wagtail chose to nest on the Fishnish-Lochaline ferry and successfully raised broods – and became quite a tourist attraction. Now Mull is busier than ever with the lure of nesting sea eagles which can be seen from viewing hides but may be encountered anywhere. An adult eagle on one occasion took off from the road verge and passed only feet from my van’s windscreen. They are impressively big. I braked hard!

Our chat on top of Talaidh was cut short by an inconsiderate flurry of snow. We scuttled off down the long easy north ridge, huge slopes to the west; westwards the whole of Glen Cannel seemed to be in flames with arcs of fire zipping up the hills and rolling great clouds of smoke into the air. Looked at from lower down, it seemed like the setting for some epic war film. Red deer pranced around in obvious distrust of this strange, fiery world. Thankfully our transverse glen had not been set alight.

Tomsleibhe bothy was once a small farmstead with signs of other ruined buildings around it. First mentioned in a 1494 charter, it survived the Clearances of Glen Forsa to become the home of a shepherd. A tight little stone cottage with a slate roof, there are three rooms inside, the walls are whitewashed, there’s an original fireplace (we lit a fire just to dry off sweaty garments), essential large table etc. Lying off popular routes, it seems to keep vandal-free. And full marks to the MBA enthusiasts who look after the bothy (it was re-roofed in 2016). Supper I recorded: a tin of chicken supreme, then a bolognese, apple flakes, and soup (in that order) and plenty more to drink. All that time we were aware of those fires in front and behind, flickering and dying and flaring up again. We had one of those gloamings ‘when birds are shapes on coloured sky/and beat their flights without a cry’. Even after dark the gold eyes of fire glanced along the slopes of Glen Forsa. We had stars after dark, a naming of stars, a touch of infinity. The Andromeda galaxy, our nearest, could just be seen by eye, yet the light we were seeing began its journey to us two and a half million years ago.

Frequent notes in the bothy book mentioned the crashed aircraft. (Most such sites are cleared.) One writer said he had turned down a lift on that very flight while stationed in Iceland. The crash date was 1st February 1945, the plane a Dakota on a Canada-Prestwick flight. When we went into the church hall in Salen two days later, a framed citation told us a few more details. Surprisingly, while three crew died, there had been five survivors; one managed to make his way off the hill in deep snow. Local rescuers set out in ‘the worst conditions in living memory’. Dr Flora MacDonald was given an MBE, there were three BEMs awarded and various other commendations for the rescuers. A piece of the Dakota’s cockpit hangs in the Tobermory museum. (A twisted propeller from the plane has now been set up in Glen Forsa as a monument to the tragedy.)

The bothy book also had many entries complaining about heat. ‘The guide says Mull is one of the wettest of islands. Rubbish!’ I wonder if that writer stayed on the island long enough to realise the guide’s veracity. I can only think most of the visitors came to Mull because the weather was good – at the time. Sadly, most entries also pointed out the brief nature of visits: the minimum required to grab Ben More – minimalist Munro-bagging. There had been couples there the previous two nights. Colin stuffed bags full of soft grass as padding on the bed-shelf.

When I looked out of the skylight in the morning, it was to discover that the meteorological fire brigade had arrived in the night and dampened down everything. We rose at our usual ‘06.30 up, 07.30 off’ to exit while the rain held off. Only as we were passing southwards under the eastern slopes of Beinn Bheag, Talaidh’s lesser neighbour, did we discover that both sides of Glen Forsa had been fired. Our boots were soon black and messy while the dog’s underparts were many times worse. At one stage he slipped and covered his face in clinging black soot.

We washed the dog once we ran out of the burnt area and made the campervan we’d left in Glen More just before the rain came on. No matter how many days of good weather you may have on Mull, it is still one of the wettest islands in the west. One day Colin will realise how lucky he was. (He knows. He and his wife now live in Appin, with Mull in their view.)

A buzzard flew up from a wayside telegraph pole. The island seems to have scores of the birds, and Colin wondered where they had perched before man erected these uprights. We drove up over the Glen More pass through boiling cloud. The rain eased. Then we saw where the early smoke of yesterday had come from. All the eastern flanks of Ben More were black. I groaned. Somewhere up there lay our cache of tents and other odds and ends. As we approached we could see some of the items peering through the black fur of burnt grass. The Ultimate Tramp tent was melted into a lump of green goo and the gas cartridges had no doubt added their contribution to the conflagration but, when ready to weep, under it all, unharmed, I found my cherished old Challis tent. I would have sacrificed a dozen others for it – my friend of the months of the Munros-in-one trip, of part of the Groat’s End Walk, of visits to Atlas and Arctic and to the Nanda Devi Sanctuary!

I’d been rather wondering why whole hillsides were being burned, a practice I’d not seen elsewhere. Selective burning of heather is common enough but here whole hillsides of grass were ablaze. Moorburn is, shall we say, a hot topic, its value open to question and its practice too often less careful than might be desired. Mull obviously has its own tradition – perhaps a practice unlikely to rage out of control, given the usual weather on the island.

As we were loading the van the Iona Ferry bus drew up. The driver asked if we had had a good trip. ‘Great, just great,’ we replied. He looked at the wall of rain sweeping up Loch Scridain. ‘You were lucky’. But that new storm was nothing to some I’ve met on Mull. I described my worst night ever in a campervan. Parked on the Ross of Mull, I had to hold my supper pan on the wobbling cooker (gimbals are not part of a camping car’s standard equipment) and I hardly slept as I feared the van was going to be blown over the cliff where I was perched. I was frightened enough to climb out of bed to drive on to find a less exposed spot, one not far from a place called Pottie – which I thought appropriate. If you must have it bad there is a certain satisfaction in having it memorably so.

But my memories of Mull are many and varied: finding a way on to Erraid island, the sunset bonfire by Loch Scridain at the start of my walk over all the Munros, Glen More echoing to the curdling cries of curlews, the Captain Scott’s anchor dragging in Tobermory Bay in the middle of the night, a ceilidh in the pub at Salen after we’d walked across the island, otter sightings at Dhiseig . . . To me, these are all part of the joys of being in the mountains, or on an island. On Mull you have the best of many worlds – and for this Easter visit, we added on a variant new memory: Mull aflame.

Across Sutherland and Caithness