2,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Archibald Forbes

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

The British Military Service is fertile in curious contrasts. Among the officers who sailed from England for the East in the spring of 1854 were three veterans who had soldiered under the Great Duke in Portugal and Spain. The fighting career of each of those men began almost simultaneously; the senior of the three first confronted an enemy's fire in 1807, the two others in the following year.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

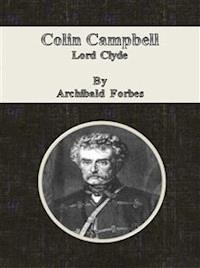

Colin Campbell

Lord Clyde

By

Archibald Forbes

Table of Contents

CHAPTER I. EARLY LIFE—THE PENINSULA

CHAPTER II. COLONIAL AND HOME SERVICE

CHAPTER III. CHINA AND INDIA

CHAPTER IV. THE CRIMEA

CHAPTER V. THE INDIAN MUTINY—ORGANISATION—RELIEF OF LUCKNOW—DEFEAT OF GWALIOR CONTINGENT

CHAPTER VI. THE STORMING OF LUCKNOW

CHAPTER VII. THE CAMPAIGN IN ROHILCUND

CHAPTER VIII. THE CAMPAIGN IN CENTRAL INDIA

CHAPTER IX. THE PACIFICATION OF OUDE—END OF THE MUTINY

CHAPTER X. FROM SIMLA TO WESTMINSTER ABBEY

FOOTNOTES:

SIR COLIN CAMPBELL, LORD CLYDEAfter the Picture by Sir Francis Grant, P.R.A.

CHAPTER I.EARLY LIFE—THE PENINSULA

The British Military Service is fertile in curious contrasts. Among the officers who sailed from England for the East in the spring of 1854 were three veterans who had soldiered under the Great Duke in Portugal and Spain. The fighting career of each of those men began almost simultaneously; the senior of the three first confronted an enemy's fire in 1807, the two others in the following year. In 1854 one of these officers, who was the son of a duke and who had himself been raised to the peerage, was the Commander-in-Chief of the expeditionary army. Lord Raglan was a lieutenant-colonel at the age of twenty-four, a colonel at twenty-seven, a major-general at thirty-seven. He had been colonel-in-chief of a regiment since 1830 and a lieutenant-general since 1838; and he was to become a field-marshal before the year was out. Another, who belonged, although irregularly, to an old and good family, whose father was a distinguished if unfortunate general, and who enjoyed the patronage and protection of one of our great houses, belonging though he did to an arm of the service in which promotion has always been exceptionally slow, was a lieutenant-colonel at thirty and a colonel at forty, and was now a lieutenant-general on the Staff and second in command of the expeditionary force. The third, who was the son of a Glasgow carpenter, sailed for the East, it is true, with the assurance of the command of a brigade; but, after a service of forty-six years, his army-rank then and for three months later, was still only that of colonel. Neither Lord Raglan nor Sir John Burgoyne had ever heard a shot fired in anger since the memorable year of Waterloo; but during the long peace both had been attaining step after step of promotion, and holding lucrative and not particularly arduous offices. Since the Peninsular days Colin Campbell had been soldiering his steadfast way round the world, taking campaigns and climates alike as they came to him in the way of duty,—now a brigade-major, now serving and conquering in the command of a division, now holding at the point of the bayonet the most dangerous frontier of British India against onslaught after onslaught of the turbulent hill-tribes beyond the border. He had fought not without honour, for his Sovereign had made him a Knight of the Bath and appointed him one of her own aides-de-camp. But there is a certain barrenness in honours when unaccompanied by promotion, and it had fallen to the lot of the son of the Glasgow carpenter to serve for eighteen years in the capacity of a field-officer commanding a regiment.

Yet even in the British military service the aphorism occasionally holds good, that everything comes to him who knows how to wait. Colin Campbell, the half-pay colonel of 1854, was a full general in 1858 and a peer of the realm in the same year; in 1862 he was gazetted a field-marshal. In less than nine years the half-pay colonel had attained the highest rank in the service,—a promotion of unique rapidity apart from that conferred on soldiers of royal blood. Along with Lord Clyde were gazetted field-marshals Sir Edward Blakeney and Lord Gough, both of whom were lieutenant-generals of some twenty years' standing when Colin Campbell was merely a colonel. Sir John Burgoyne, almost immeasurably his senior in 1854, did not become a field-marshal until 1868.

Colin Campbell was born in Glasgow on the 20th of October 1792, the eldest of the four children of John Macliver, the Glasgow carpenter, and his wife Agnes Campbell. How Colin Macliver came to bear the name of Colin Campbell will presently be told. The family had gone down in the world, but Colin Campbell came of good old stock on both sides of the house. His grandfather, Laird of Ardnave in the island of Islay, had been out in the Forty-five and so forfeited his estate. General Shadwell, the biographer of Colin Campbell, states that his mother was of a respectable family which had settled in Islay near two centuries ago with its chief, the ancestor of the existing Earls of Cawdor. But the Campbell who was the ancestor of the Cawdors was a son of the second Earl of Argyle who fell at Flodden in 1513, and he belonged to the first half of the sixteenth century; so that, since Colin Campbell's maternal family settled in Islay with its chief, it could reckon a longer existence than that ascribed to it by General Shadwell. Not a few of Colin Campbell's kinsmen had served in the army; and the uncle after whom he was christened had fallen as a subaltern in the war of the American Revolution.

His earliest schooling he received at the Glasgow High School, whence at the age of ten he was removed by his mother's brother, Colonel John Campbell, and placed by him in the Royal Military and Naval Academy at Gosport. Scarcely anything is on record regarding young Colin's school-days there. The first Lord Chelmsford was one of his schoolfellows; and there is a tradition that he spent his holidays with the worthy couple by whom the Academy was established, and by a descendant of whom it is still carried on. When barely fifteen and a half his uncle presented him to the Duke of York, then Commander-in-Chief, who promised him a commission; and supposing him to be, as he said, "another of the clan," put down his name as Colin Campbell, the name which he thenceforth bore. General Shadwell states that on leaving the Duke's presence with his uncle, young Colin made some comment on what he took to be a mistake on the Duke's part in regard to his surname, to which the shrewd uncle replied by telling him that "Campbell was a name which it would suit him, for professional reasons, to adopt." The youngster was wise in his generation, and does not appear to have had any compunction in dropping the not particularly euphonious surname of Macliver. On the 26th of May 1808 young Campbell received the commission of ensign in the Ninth Foot, now known as the Norfolk regiment; and within five weeks from the date of his first commission he was promoted to a lieutenancy in the same regiment.

He entered the service at an eventful moment. Napoleon had attained the zenith of his marvellous career. He was the virtual master of the whole of continental Europe. The royal family of Spain were in effect his prisoners, and his brother Joseph had been proclaimed King of Spain. The royal family of Portugal had departed to the New World lest worse things should befall it, and Junot was ruling in Lisbon in the name of his imperial master. But the Spaniards rose en masse in a national insurrection; and no sooner had they raised the standard of independence than they felt the necessity of applying to England for aid. Almost simultaneously the Portuguese rose, and no severity on Junot's part availed to crush the universal revolt. Almost on the very day on which young Campbell joined his regiment in the Isle of Wight, the British force of nine thousand men to the command of which Sir Arthur Wellesley was appointed, sailed from Cork for the Peninsula. Spencer's division joined Wellesley in Mondego Bay, and on the night of the 8th of August 1808 thirteen thousand British soldiers bivouacked on the beach—the advanced guard of an army which, after six years of many vicissitudes and much hard fighting, was to expel from the Peninsula the last French soldier and to contribute materially to the ruin of Napoleon.

Campbell was posted to the second battalion of the Ninth, commanded by Colonel Cameron, an officer of whom he always spoke with affectionate regard. The first battalion of the regiment had already sailed from Cork, and the second, which belonged to General Anstruther's brigade, took ship at Ramsgate for the Peninsula on July 20th. Reaching the open sandy beach at the mouth of the Maceira on the 19th of August, it was disembarked the same evening, and bivouacked on the beach. Campbell notes, "lay out that night for the first time in my life;" many a subsequent night did he lie out in divers regions! On the following day the battalion joined the army then encamped about the village of Vimiera. Wellesley had only landed on the 8th, but already he had been the victor in the skirmish of Obidos and the battle of Roleia; and now, on the 21st, he was again to defeat Junot on the heights of Vimiera.

Directly in front of the village of that name rose a rugged isolated height, with a flat summit commanding the ground in front and to the left. Here was posted Anstruther's brigade, its left resting on the village church and graveyard. Young Campbell was with the rear company of his battalion, which stood halted in open column of companies under the fierce fire of Laborde's artillery covering the impending assault of his infantry. The captain of Campbell's company, an officer inured to war, chose the occasion for leading the lad out to the front of the battalion and walking with him along the face of the leading company for several minutes, after which little piece of experience he sent him back to his company. In narrating the incident in after years Campbell was wont to add: "It was the greatest kindness that could have been shown to me at such a time, and through life I have been grateful for it." It is not unlikely that the gallant and considerate old soldier may have intended not alone to give to his young subaltern his baptism of fire, but also to brace the nerves of the men of a battalion which, although part of a regiment subsequently distinguished in many campaigns and battles, was now for the first time in its military life to confront an enemy and endure hostile fire.

The brigade was assailed at once in front and flank. The main French column, headed by Laborde in person and preceded by swarms of tirailleurs, mounted the face of the hill with great fury and loud shouts. So impetuous was the onset that the British skirmishers were driven in upon the lines, but steady volleys arrested the advance of the French, and they broke and fled without waiting for the impending bayonet charge. It would be interesting to know something of the impressions made on young Campbell by his first experience of actual war; but the curt entry in his memorandum is simply—"21st (August), was engaged at the battle of Vimiera."

At the end of the brief campaign Campbell was transferred to the first battalion of the Ninth, and had the good fortune to remain under the command of Colonel Cameron, who had also been transferred. In the beginning of October a despatch from England reached Lisbon, instructing Sir John Moore to take command of the British army intended to co-operate with the forces of Spain in an attempt to expel the French from the Peninsula. The disasters which befell the enterprise committed to Moore need not be recounted in detail because of the circumstance that a young lieutenant shared in them in common with the rest of the hapless force. The battalion in which Campbell was serving was among the earliest troops to be put in motion. It quitted its quarters at Quelus, near Lisbon on October 12th, and reached Salamanca on November 11th. When Moore's army was organised in divisions, the battalion formed part of Major-General Beresford's brigade belonging to the division commanded by Lieutenant-General Mackenzie Fraser. On reaching Salamanca Moore found that the Spanish armies which he had come to support were already destroyed, and that he himself was destitute alike of supplies and money. In this situation it was his original intention to retire into Portugal, which might have been his wisest course; but Moore was a man of a high and ardent nature. When on the point of taking the offensive in the hope of affording to the Spaniards breathing-time for organising a defence of the southern provinces, he became aware that French forces were converging on him from diverse points; and on the 24th of December began the memorable retreat, the disasters of which cannot be said to have been compensated for by the nominal victory of Coruña.

In the hardships and horrors of that midwinter retreat young Campbell bore his share. Little, if any fighting came in his way, since the division to which his battalion belonged was for the most part in front. During the retreat it experienced a loss of one hundred and fifty men; but they are all specified as having died on the march or having been taken prisoners by the enemy. Nor had it the good fortune to take part in the battle of Coruña, having been stationed in the town during the fighting. There fell to a fatigue party detailed from it the melancholy duty of digging on the rampart of Coruña the grave of Moore, wherein under the fire of the French guns he was laid in his "martial cloak" by his sorrowing Staff in the gray winter's dawn. Beresford's brigade, to which Campbell's battalion belonged, covered the embarkation and was the last to quit a shore of melancholy memory. General Shadwell writes that, "To give some idea of the discomforts of the retreat, Lord Clyde used to relate how for some time before reaching Coruña he had to march with bare feet, the soles of his boots being completely worn away. He had no means of replacing them, and when he got on board ship he was unable to remove them, as from constant wear and his inability to take them off the leather had adhered so closely to the flesh of the legs that he was obliged to steep them in water as hot as he could bear and have the leather cut away in strips—a painful operation, as in the process pieces of the skin were brought away with it."

After a stay in England of little more than six months Campbell's battalion was again sent on foreign service, an item of the fine army of forty thousand men under the command of the Earl of Chatham. The main object of the undertaking, which is known as the Walcheren Expedition, whose story occupies one of the darkest pages of our military history, was to reduce the fortress of Antwerp and destroy the French fleet lying under its shelter, in the hope of disconcerting Napoleon and creating a diversion in favour of Austria. But opportunities were lost, time was squandered, and the expedition ended in disastrous failure. Montresor's brigade, to which Campbell's battalion belonged, disembarked on the island of South Beveland in the beginning of August, to be the gradual prey of fever and ague in the pestilential marshes of the island. Nothing was achieved save the barren capture of the fortress of Flushing; and towards the end of September most of the land forces of the expedition, including Campbell's battalion, returned to England. Over one-sixth of the original army of forty thousand men had been buried in the swamps of Walcheren and South Beveland; the survivors carried home with them the seeds of the "Walcheren fever," which affected them more or less for the rest of their lives. Colin Campbell was an intermittent sufferer from it almost if not quite to the end of his life.

The second battalion of the Ninth had been in garrison at Gibraltar since July, 1809, and to it Colin Campbell was transferred some time in the course of the following year. In the beginning of 1811 the French Marshal Victor was blockading Cadiz, and General Graham (afterwards Lord Lynedoch) determined on an attempt in concert with a Spanish force to march on his rear and break the blockade. Landing at Tarifa he picked up a detachment, which included the flank companies of the Ninth in which Campbell was serving. Graham's division of British troops was now somewhat over four thousand strong, and the Spanish army of La Peña was at least thrice that strength. The allied force reached the heights of Barrosa on March 5th. Graham anxiously desired to hold that position, recognising its value; but he had ceded the command to La Peña, who gave him the order to quit it and move forward. In the conviction that La Peña himself would remain there, he obeyed, leaving on Barrosa as baggage-guard the flank companies of the Ninth and Eighty-Second regiments under Major Brown. Graham had not gone far when La Peña abandoned the Barrosa position with the mass of his force. Victor had been watching events under cover of a forest, his three divisions well in hand; and now he saw his opportunity. Villatte was to stand fast; Laval to intercept the return of the British division to the height; Ruffin to seize the height, sweep from it the allied rear-guard left there, and disperse the baggage and followers. Major Brown held together the flank companies he commanded, and withdrew slowly into the plain. Graham promptly faced about and made haste to attack. Brown had sent to Graham for orders, and was told that he was to fight; and the gallant Brown, unsupported as he was, charged headlong on Ruffin's front. Half his detachment went down under the enemy's first fire; but he maintained the fight staunchly until Dilke's division came up, when the whole, Dilke's people and Brown's stanch flank companies, "with little order indeed, but in a fierce mood," in Napier's words, rushed upwards to close quarters. The struggle lasted for an hour and a half and was "most violent and bloody"; only the unconquerable spirit of the British soldiers averted disaster and accomplished the victory. Many a fierce fight was Colin Campbell to take part in, but none more violent and bloody than this one on the heights of Barrosa. His record of his own share in it is characteristically brief and modest: "At the battle of Barrosa Lord Lynedoch was pleased to take favourable notice of my conduct when left in command of the two flank companies of my regiment, all the other officers being wounded."

Late in the same year Campbell saw some casual service while temporarily attached to the Spanish army commanded by Ballasteros in the south of Spain. In the disturbed state of the surrounding region many Spanish families of rank were glad to find quiet shelter within the fortress of Gibraltar, and their society was eagerly sought by young Campbell, who was anxious to take the opportunity of improving himself in the French and Spanish languages. When in December, 1811, a French force under Laval undertook what proved an abortive and final attempt to reduce the fortified town of Tarifa, he accompanied the light company of his battalion to take part in the vigorous and successful defence of the place, a result achieved by the courage and devotion of the British garrison sent to hold it by General Campbell, the wise and energetic governor of Gibraltar, and by the skill and resource of Sir Charles Smith the chief engineer.

At the close of 1812 Colin Campbell had just turned his twentieth year, and had been a soldier for four and a half years, during which time he had seen no small variety of service. Vimiera and Barrosa had been stiff fights, but neither belonged to the category of "big wars" which are said to "make ambition virtue." Young Campbell had virtue, and certainly did not lack honest ambition. In a sense he had as yet not been very fortunate. In a period when interest was almost everything, he had absolutely none. While he had been on a side track of the great war, his more fortunate comrades of the first battalion had fought at Busaco and Salamanca under the eye of the Great Captain himself. But the time had now come when he, too, was to belong to the army which Wellington was to lead to final and decisive victory. He accompanied a draft from the second battalion of his regiment which in January 1813 was sent to join the first battalion lying in its winter cantonments in the vicinity of Lamego on the lower Douro, and to his great joy found himself again under the command of his original chief, Colonel Cameron. In its winter quarters the allied army had recovered the cohesion and discipline so sadly impaired during the retreat from Burgos in the preceding autumn, and, strengthened by large reinforcements, was now in fine form and high heart. The advance began in the middle of May, when Wellington's army, seventy thousand strong, swept onward on a broad front, turning the positions of the French and driving them before it towards the Pyrenees. Of the three corps constituting that army Sir Thomas Graham's had the left, consisting of the first, third, and fifth divisions, to the second brigade of which, commanded by General Hay, belonged the first battalion of the Ninth, to the light company of which Colin Campbell was posted. The march of Graham's corps through the difficult mountainous region of Tras-os-Montes and onward to Vittoria was exceptionally arduous, but the obstacles were skilfully surmounted. Of the part taken by his battalion on this advance Colin Campbell kept a minute daily record, which has been preserved. He acted as orderly officer to Lieutenant-Colonel Crawford of his battalion, who commanded the flank companies of the third and fifth divisions in the operation of crossing the Esla at Almandra on May 31st. Continuing its march towards the north-east Graham's corps crossed the Ebro with some skirmishing, and on the morning of the 18th of June its advance debouched from the defile of Astri and marched on Osma, where the French General Reille with two divisions was unexpectedly met. Reille occupied the heights of Astalitz. The light companies of the first brigade were sent against the enemy, who were evincing an intent to retreat, and Campbell accompanied his company. He notes as follows:—"This being our first encounter of the campaign, the men were ardent and eager, and pressed the French most wickedly. When the enemy began their movement to the rear, they were constrained to hurry the pace of their columns, notwithstanding the cloud of skirmishers which covered their retreat. Lord Wellington came up about half-past three. We continued the pursuit until dusk, when we were relieved by the light troops of the fourth division. The ground on which we skirmished was so thickly wooded and so rugged and uneven, that when we were relieved by the fourth division, and the light companies were ordered to return to their respective regiments, I found myself incapable of further exertion from fatigue and exhaustion, occasioned by six hours of almost continuous skirmishing."

On the 20th Wellington's army moved down into the basin of Vittoria. King Joseph's dispositions for the battle of Vittoria, which was fought on June 21st, were distinctly bad. His right flank at Gamara Mayor was too distant to be supported by the main body of his army, yet the safe retreat of the latter in the event of defeat depended on the staunchness of this isolated wing. Graham, moving southward from Murguia by the Bilbao road, was to attack Reille who commanded the French right, and to attempt the passage of the Zadora at Gamara Mayor and Ariaga; should he succeed, the French would be turned, and in great part enclosed between the Puebla mountains on one side and the Zadora on the other by the corps of Hill and Wellington.

Graham approached the valley of the Zadora about noon. Before moving forward on the village of Abechuco, it became necessary to force across the river the enemy's troops holding the heights on the left and covering the bridges of Ariaza and Gamara Mayor. This was accomplished after a short but sharp fight in which Colin Campbell participated. Sarrut's French division retired across the stream, and the British troops occupied the ground from which the enemy had been driven. Campbell thus describes the sequel:—"While we were halted the enemy occupied Gamara Mayor in considerable force, placed two guns at the principal entrance into the village, threw a cloud of skirmishers in front among the cornfields, and occupied with six pieces of artillery the heights immediately behind the village on the left bank. About 5 P.M. an order arrived from Lord Wellington to press the enemy in our front. It was the extreme right of their line; and the lower road leading to France, by which alone they could retire their artillery and baggage, ran close to Gamara Mayor. The left brigade moved down in contiguous columns of companies, and our light companies were sent to cover the right flank of this attack. The regiments, exposed to a heavy fire of musketry and artillery, did not take a musket from the shoulder until they carried the village. The enemy brought forward his reserves, and made many desperate efforts to retake the bridge, but could not succeed. This was repeated until the bridge became so heaped with dead and wounded that they were rolled over the parapet into the river below. Our light companies were closed upon the Ninth, and brought into the village to support the second brigade. We were presently ordered to the left to cover that flank of the village, and we occupied the bank of the river, on the opposite side of which was the enemy. After three hours' hard fighting they retired, leaving their guns in our possession. Crossing the Zadora in pursuit, we followed them about a league, and encamped near Metanco." The French left and centre had been driven in, and Graham had closed to the enemy their retreat by the Bayonne road, so that there remained to them only the road leading towards Pampeluna, which was all but utterly blocked by vehicles and fugitives. In the words of one of themselves, the French at Vittoria lost all their equipages, all their guns, all their treasure, all their stores, all their papers, so that no man could prove even how much pay was due to him; generals and subordinate officers alike were reduced to the clothes on their backs, and most of them were barefooted.

After the battle of Vittoria Graham moved forward to the investment of San Sebastian. In itself before that battle the fortress was of little account, but since then the French General Rey had used great energy in restoring its powers of defence; and its garrison at the beginning of Graham's operations reached a total of about three thousand men. San Sebastian is situated on a peninsula jutting out into the sea, and is connected with the mainland by a narrow isthmus. The western side of the peninsula is washed by the sea, the eastern by the estuary of the river Urumea. At its northern extremity rose the steep height of Monte Urgullo, the summit of which was occupied by the castle of La Mota, a citadel of great strength, capable of being defended after the town should have fallen. The town, surrounded by a fortified enceinte, occupied the entire breadth of the peninsula. The high curtain protecting it on the southern or landward side had in front of it a large hornwork, with a ravelin enclosed by a covered way and glacis. The east and west defences were weak; along the eastern side the water of the Urumea estuary receded at low tide for some distance from the foot of the wall, leaving access thereto from the isthmus. At the neck of the peninsula, about half a mile in advance of the town defences, was the height of San Bartolomeo, near the eastern verge of which was the convent of the same name. This building the French had fortified and had thrown up a redoubt in connection with it, convent and redoubt forming the advanced post of the garrison.

Graham was in command of the operations, his force amounting to about ten thousand men. The obvious preliminary was the capture of the redoubt and convent of San Bartolomeo. An attack on this position, made on the 14th of July after an artillery preparation, had failed with heavy loss. A second attempt made on the 17th was more successful, three days of unintermitting artillery fire having reduced the convent to ruins and silenced the redoubt. The attack was made in two columns, the right one of which Colin Campbell accompanied with his own, the light company. The chief fighting of the day was done by his regiment, which stormed both convent and redoubt and after some hard fighting drove the French out of the adjacent suburb of San Martino and occupied what fire had spared of it. In this affair the Ninth lost upwards of seventy officers and soldiers. Campbell's laconic entry in his journal for this day is simply, "Convent taken." But he must have distinguished himself conspicuously, since in Graham's despatch to Lord Wellington, among "the officers whose gallantry was most conspicuous in leading on their men to overcome the variety of obstacles exposed to them" was mentioned "Lieutenant Colin Campbell of the Ninth Foot."

The Commander-in-Chief desired judicious speed, and the operations were hurried on unduly by men who were too impetuous to adhere to the scheme sanctioned by their chief. After a four days' bombardment of the place the assault was ordered for the early morning of the 25th. The storming-party consisted of a battalion of the Royals, with the task of carrying the great breach; of the Thirty-Eighth, told off to assail the lesser breach further to the right; and of the Ninth, to act in support of the Royals. Colin Campbell had a special position and a special duty, of a kind seldom entrusted to a subaltern and markedly indicative of the estimation which he had thus early earned. He was placed in the centre of the Royals with twenty men of his (the light) company, having the light company of the Royals as his immediate support and under his orders, and accompanied by a ladder-party under an engineer officer. His specific orders were on reaching the crest of the breach to gain the ramparts on the left, sweep the curtain to the high work in the centre of the main front, and there establish himself. The signal for an advance to the assault was given prematurely, while it was still dark, by the explosion of a mine, and the head of the storming-party moved out of the trenches promptly but in straggling order. The space between the exit from the parallel and the breach, some three hundred yards, was very rugged, broken by projecting rocks, pools, seaweed and other impediments. These difficulties, the darkness, and the withering fire from the ramparts, increased the tendency to disorder, and presently Campbell was not surprised to find an actual check. The halted mass had opened fire and there was no moving it forward. He pushed on past the halted body having there lost some men of his detachment; and reached the breach, the lower part of which he observed to be thickly strewn with killed and wounded. "There were," to quote from his journal, "a few individual officers spread on the face of the breach, but nothing more. These were cheering, and gallantly exposing themselves to the close and destructive fire directed on them from the round tower and other defences. In going up I passed Jones of the Engineers[1] who was wounded; and on gaining the top I was shot through the right hip and tumbled to the bottom. Finding on rising that I was not disabled from moving, and observing two officers of the Royals who were exerting themselves to lead some of their men from under the line-wall near to the breach, I went to assist their endeavours and again went up the breach with them, when I was shot through the inside part of the left thigh." In the language of the brilliant historian of the Peninsular War—"It was in vain that Lieutenant Campbell, breaking through the tumultuous crowd with the survivors of his chosen detachment, mounted the ruins—twice he ascended, twice he was wounded, and all around him died."

The assault failed; and the siege of San Sebastian was temporarily exchanged for a blockade. There was much angry discussion and recrimination as to the causes of the disastrous issue. It was remarked that no general or staff officer had quitted the trenches, and that what leading there was devolved entirely on the regimental officers. They, at least, had fought well and exposed themselves freely, and none had behaved himself more gallantly than Colin Campbell. This was heartily and handsomely acknowledged by Graham when he thus wrote in his despatch to Lord Wellington describing the assault:—"I beg to recommend to you Lieutenant Campbell of the Ninth, who led the forlorn hope, and who was severely wounded in the breach." Such a recognition, barren of immediate results though it was, Colin Campbell probably thought cheaply earned at the cost of a mere couple of bullet-holes. These, however, hindered him from participating in the desperate fighting of the final and successful assault on San Sebastian; and, indeed, when after the surrender of the place his division departed, he had to remain an invalid in the shattered town. He was now about to perpetrate the only breach of military discipline ever laid to his charge. Having heard of the early prospect of a battle, he and a brother officer who had also been wounded took the liberty of deserting from hospital for the purpose of joining their regiment. How long it took them to limp from San Sebastian to Oryarzun is not specified; but they reached the regiment on October 6th just in time to join the midnight march to the left bank of the Bidassoa opposite Andaya, and on the following morning to wade the river and enter France. The British cannonade awoke the French to find their country invaded by an enemy and hostile cannon-balls falling in their bivouacs.