Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Daphne Press

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

A gut-wrenching page-turner about rebellion and trans rage following a teen who survives attempted murder and the ghosts who seek vengeance in the Appalachian mountains. On the night Miles Abernathy—sixteen-year-old socialist and proud West Virginian—comes out as trans to his parents, he sneaks off to a party, carrying evidence that may finally turn the tide of the blood feud plaguing Twist Creek: Photos that prove the county's Sheriff Davies was responsible for the so-called "accident" that injured his dad, killed others, and crushed their grassroots efforts to unseat him. The feud began a hundred years ago when Miles's great-great-grandfather, Saint Abernathy, incited a miners' rebellion that ended with a public execution at the hands of law enforcement. Now, Miles becomes the feud's latest victim as the sheriff's son and his friends sniff out the evidence, follow him through the woods, and beat him nearly to death. In the hospital, the ghost of a soot-covered man hovers over Miles's bedside while Sheriff Davies threatens Miles into silence. But when Miles accidently kills one of the boys who hurt him, he learns of other folks in Twist Creek who want out from under the sheriff's heel. To free their families from this cycle of cruelty, they're willing to put everything on the line—is Miles?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 428

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Available from Andrew Joseph White and Daphne Press

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Letter from the Author

Twist Creek Calamity

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Available from Andrew Joseph Whiteand Daphne Press

Hell Followed with Us

The Spirit Bares Its Teeth

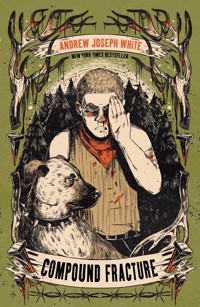

Compound Fracture

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

First published in the United States under the title COMPOUND FRACTURE by Andrew Joseph White.

First published in the UK in 2024 by Daphne Press.

www.daphnepress.com

Text Copyright © 2024 by Andrew Joseph White

Cover design by Jane Tibbetts

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Published in arrangement with Peachtree Publishing Company Inc.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher.

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-83784-075-5

eBook ISBN: 978-1-83784-076-2

1

For my family.This one is about you.

—A. J. W.

LETTER FROM THE AUTHOR

Hopefully, by the time this book goes to print, I’ll have scrapped this letter and written a new one.

I mean it. I’m desperate to write a different intro to this thing. If I do write a new one, I’ll write about how much I love West Virginia. I’ll write about family reunions in the mountains, and steep switchback roads, and venison in the freezer, and my half-remembered Appalachian drawl and and and.

Instead, I have to write about how tough it is to be trans in America right now. By the time Compound Fracture is released, I’ll be twenty-six years old, and I’ll have seen bathroom bills, state-sponsored attempts to remove trans kids from supportive parents, crackdowns on gender-related care, and so much more. And if you’re disabled on top of it? Christ.

I guess what I’m saying is, I’m sorry it’s so difficult. We shouldn’t have to fight so hard to exist. We deserve better.

But, of course, this is a book about fighting as hard as you can. So please note that we’re going to deal with some difficult topics: graphic violence including police violence, transphobia, opioid use and withdrawal, and disturbing images. This is a book about an autistic, queer trans kid who loves his family and all the people who love him back . . . as well as all the people who want him dead. Actually, this book is kind of like moonshine. It’s gonna burn like hell going down.

And, well, looks like this author’s note is still here.

If I promise you that this book has a happy ending, does that make it better? Does that make any of it easier to swallow?

Yours,

Andrew

TWIST CREEK CALAMITY

Part of the West Virginia coal wars

This article is about the 1917 strike. For the preceding mining accident, seeNorth Mountain Coal Company disaster of 1917.

DateMay 27 to June 4, 1917LocationTwist Creek County, West VirginiaResulted inLaw enforcement victory• 40–50 killed • 200 arrested• Execution of strike leader Saint AbernethyThe Twist Creek Calamity, or the McLachlan-Pearson labor riot of 1917, was a confrontation between striking coal miners and mine operators, the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency, and law enforcement. Though the strike unofficially began on May 24, after the North Mountain Coal Company disaster of 1917, the kidnapping of Joseph Davenport by striker Saint Abernethy marked the official start of the incident. It is also one of the only confrontations of the coal wars to occur in the northern coalfields of West Virginia as opposed to further south.

While one of the deadliest labor conflicts in American history, it is often overlooked due to a lack of reporting or firsthand accounts.

This article is a stub.

CHAPTER

1

When the sheriff of Twist Creek County—and all those other sons of bitches, the Baldwin-Felts agents and bloodthirsty strikebreakers—finally caught my great-great-grandfather and dragged his ass up from the mine to make a spectacle of his execution, they killed him by hammering a railroad spike through his mouth.

That’s what they did to labor strikers a hundred years ago—machine guns, spare World War I munitions, railroad spikes. And I don’t know if you’ve gone and picked up a railroad spike before, but they’re big. Big enough that my great-great-grandfather must have choked on it. He must have gagged waiting for the hammer to come down. One time I opened Dad’s toolbox and put a big rusty nail between my teeth and held it there, breathing around the metal, trying to imagine how it’d be to go and die like that.

Our family name is misspelled in the article, by the way. It’s Abernathy. Not Abernethy.

CHAPTER

2

Last week, I stole a fistful of old photos, made exactly three sets of copies at the school library, and put the originals safely back in Dad’s lockbox. The originals are blurry, and the scanner made it worse, but it’s enough. Twisted metal and out-of-focus fire, Mrs. O’Brien’s charred corpse almost visible if you squint. I have one of the sets now: all the photos on the same piece of cheap printer paper, folded twice and jammed in my pocket.

But before I sneak out to the graduation party and make a mess of things, I check on my parents.

My dog, Lady, trails behind me as I slip out of my room. “Shh,” I whisper, crinkling her ears. She huffs. “Don’t fuck me on this.”

Mom’s in bed for once. She sleeps all curled up, knee to her chest and wrists tucked under her chin. I get that from her. She has the fan going too, full blast even though summer rarely gets warm enough to justify it, with the corner of grandma’s quilt clutched tight in her hands. She deserves the rest. Nursing home’s been running her ragged. I leave her be.

Dad, though, is passed out at his computer. The light of the screensaver makes the living room look strange; it washes out the camo-print blanket and reflects in the glass eyes of the deer head over the TV. I step carefully, avoiding the spots of the old floor that creak, and lean over my father to inspect the tangle of emails and printouts.

Election results map. West Virginia municipal guide, the running for office version. A bunch of email drafts, all unfinished, most to recipients I recognize but some I don’t. Tylenol. Discarded cane under the desk. Lockbox of photos from the accident that I definitely didn’t find the key for last week.

I should probably be excited he’s gotten it in his head—seems like he’s gonna run for a county seat again, if I’m reading all this right—but I just feel sick. After what happened last time, it’s hard not to be scared.

But that’s why I’m helping, right?

Quiet as I can, I gather the printouts in a folder and ease them into a drawer. Close the emails and PDFs. Wipe the browser history, scrub the downloads folder, clear the “Recent Items” section of the File Explorer. Lady sniffs the couch and watches me sideways, asking why the hell I’m sneaking around. Dad snores a little. In the blue light from the screen, the scars on his leg are paper white.

And then I stop. Maybe I could—

I pull out my phone and open my own email draft, a finger hovering above send.

I don’t have to send this. Full honesty, I probably shouldn’t. Mom and Dad have enough to deal with right now, because being poor means there’s always something to deal with—endless medical bills, squirreling away cash to keep the heat on this winter, fronting house repairs because our landlord can’t be bothered—and I’ve been putting this off for so long that, really, what’s a few more weeks? Months?

But whatever. I’m already doing stupid shit tonight.

I hit send.

An email notification dings on the desktop. Subject line: Mom, Dad, I’m trans. Body text: I’d say there’s something I have to tell you, but the subject line is kind of a spoiler . . . etc. etc.

Dad should thank me. If I forgot to hide something, this should cause enough of a ruckus that Mom won’t notice.

Still, before I leave, I double-check the desk and pour Dad a glass of water, because he always wakes up thirsty. The photocopies are heavy as buckshot in my pocket. The email notification on the desktop makes me itch.

Bite the bullet, Miles. Do it.

Lady sits in the kitchen, head cocked but silent. She knows when not to bark. Good girl. “Love you,” I say over my shoulder to the quiet house.

* * *

Twist Creek County High throws a graduation party every year, right on the riverbank at the bottom of the valley, a straight shot down the mountain from my house. It’s a game, apparently, seeing what all you can sneak away for it. Red jugs of gasoline, coolers for the drinks, moonshine jars from the back of the freezer. Some parents have started staying up on the last day of school with flashlights, trying to bust it, but most roll their eyes and let it happen. Nothing else to be doing round here, and I figure they’d rather their kids do this than blow shit up with their dad’s hunting rifle for fun.

I’ve never been to one before. Even if Mom and Dad weren’t so paranoid about letting me out of their sight, and rightfully so, I don’t do parties. Simple as that. Deer don’t do hunting season, rats don’t do traps, and I don’t do parties. So I’m huddled behind the snack table, chewing on the shoelace I bought specifically for chewing on, scanning the party for trouble.

I don’t got anxiety or nothing. No more than I need to stay in one piece around here, at least. I just—

I don’t know. People are too much work, and I don’t like most of them.

Anyway, I swear the whole student body of Twist Creek County High is here, throwing homework into the bonfire and drinking cheap beer, though we’re a small school so that’s only, what, two hundred people? Jared Fink—graduating senior, class clown, etc.—has CONGRATS CLASS OF 2017!!! painted on his chest. A gaggle of sophomore girls wade into the shallow water, and Skeeter’s by the fire selling oxy at a markup only freshman are dumb enough to fall for. They’d get a better deal at the urgent care half an hour south. Doctor must be getting a nice kickback for all the scripts he shits out.

So of course, we’ve got everyone out on the riverbank except Cooper O’Brien, who is the only reason I’m here. Jesus Christ. It was risky as hell getting those photos to school. Putting them in the scanner and printing out the photocopies in public bordered on dangerous. I wouldn’t have done it if I had a choice, but I didn’t, because who the hell has a personal printer? Nobody we trust, that’s for sure.

And if Cooper don’t show, I’m gonna be pissed. He said he’d be here.

“Hey, Sadie!”

The name hits like an axe. Sadie. I yank the shoelace from my mouth and Kara Simmonds comes up to the table with an awkward smile like she’s trying her best to be friendly. I don’t know why she’s trying. It ain’t like I’m friendly back. But I spent a semester doing her homework in exchange for gas money, so she thinks we’re good. Guess being the smart kid overrides both my family reputation and the fact that I growled at people in elementary school.

“Breanna’s over there,” Kara says to me, crouching to inspect the dwindling selection of stolen drinks sweating in the cooler. “If you wanted to talk to her.”

I know. Breanna’s by the fallen tree with the rest of the school’s resident queers. Not that we got a ton, but still. A he/they lesbian, the girl that defected from the popular crowd when her ex outed her, some boy who has a crush on the football captain. The usual. I keep my distance from them, though. They have it hard enough without me.

“Why would I want to talk to Breanna,” I say.

Kara straightens up with a jar of strawberry moonshine in hand. “You ain’t into girls?”

“Kara.”

“Oh my god. You’re straight? Really?”

I know the short hair and cut-up John Brown Did Nothing Wrong t-shirt would set off even the shittiest gaydar, but Kara’s got no idea what she’s on about. “You seen Cooper?”

“I—you’re into guys? No way.”

“Where is he.”

She unscrews the jar of moonshine and takes a sip. I can smell the Sharpie smell of homebrewed corn liquor from here. “This tastes like ass. Anyway, I don’t know. Let’s find out.”

She takes a breath and hollers, “O’Brien!”

I recoil. Half the party turns to face us and I’m gonna break out into hives. Why would she do that? “Kara, what the fuck—”

But, from across the party, Cooper bellows, “What?”

Instantly my stomach uncurls from its knot. Thank Christ. He’s here.

Kara winks at me. Again, like we’re friendly. “Found him.” Then she raises the moonshine. “C’mere! Sadie Abernathy wants to talk to you! Did you know she’s straight?”

There’s a small crackle of laughter, and then attention on us dissipates—a joke at the Abernathys’ expense, fine, there’s better things to do—but Cooper cuts through the crowd, nursing a Bud Light and wearing his John Deere hat backwards.

“Hey now,” he says. “You don’t gotta be yelling that everywhere.”

Cooper O’Brien. Brand new graduate of Twist Creek High. Twice my size and three times as shiny, all torn-off sleeves and sanded jeans, finishing off the can and crunching it in his fist. His dad technically manages the Sunoco stations in Twist Creek, but after the accident, his dad got sick—that’s what we call it around here, sick—so now Cooper keeps them all running the best he can. Maybe it’ll get easier now that he don’t have school to worry about no more.

We were best friends before the accident. These days, we’re . . . something? We’re friendly, sure, but we don’t talk as much, not like we used to. Things got tough and we grew up quick and, well.

“You hear me, Kara?” Cooper says, flicking the can into the limp garbage bag between us. “That’s her business, not yours.”

Kara blushes. Cooper’s got that effect on people. “Thought you’d want to know. Just don’t drink everything before my brother gets here.” She shoots me a look I think is supposed to be conspiratorial, like she’s done me some grand favor. “Later, you two.”

And then it’s just us.

Cooper folds his arms at me with a snort. “You don’t do parties.”

To preface, it ain’t my fault I’m bad with people. Or more accurately, you can’t say I haven’t tried. I spent so many years trying. Mom taught me how to smile and make eye contact, or fake it if I had to. I watched my classmates and memorized how they talked to each other, even built a book of scripts in my head: express this emotion this way, that emotion that way, on and on. And sure, I figure everyone has to do all that, but Jesus, ain’t it exhausting? Ain’t it hard remembering to smile and say the right thing and look everyone in the eye?

These days, I save the effort for the people that matter. Like my teachers, or my boss. If it means I’m an antisocial asshole to everyone else, I’ll take it. At least I’m an antisocial asshole that don’t break down in tears every day after school.

Cooper, though? It’s not as hard with Cooper. I don’t have to try so hard with him.

I think I have a crush on him, but I’m not sure.

“Parties are loud,” I say, putting the shoelace back in my mouth. “And boring.”

“I mean,” Cooper says, “of course they’re gonna be boring when you don’t drink and also have no friends.”

“Fuck off.”

Cooper laughs. “Yeah, yeah, fuck off, I know. What’s the special occasion?”

I can’t say, I found photos of the accident that killed your mom, you know, the ones my dad lied about having, and we both know he lied for a good reason and I really shouldn’t have taken these out of the house but I found them, look, we have proof.

“I, um,” I manage, pulling out the paper. “Here.”

I press the folded sheet into his hand.

“Okay,” he says slowly. “This ain’t—”

I don’t wanna hear whatever he thinks this might be. No matter what he guesses, it’ll be worse than what’s really there. “Open it.”

He does.

He goes still.

“What is this?” he chokes. He slams the paper closed and glances nervously over his shoulder. “Jesus Christ, Sadie. What are you doing?”

“I found them last week,” I say, winding the shoelace around my fingers until it starts to cut off circulation. “Dad had them. He’s been hiding them from Sheriff Davies.”

“Of course he’s hiding them from Davies.” Cooper shoves the paper in his pocket and grabs me, pulls me out from behind the table, drags me towards him. I let him. I’m too shocked to do anything else. “We ain’t talking about this here. Come on.”

Cooper leads me through the mess of people, through classmates that pity me, don’t talk to me, try not to look in my direction. Cooper may have managed to salvage a reputation in Twist Creek, but I haven’t. Even if I had the social skills for it—I’m an Abernathy. That’s how it works. I keep my eyes down until we’re at the riverbank, outside the jurisdiction of the bonfire, until it’s just the rumble of the river and the distant mutter of the radio.

Here, Cooper takes a deep breath.

I can see why someone would have a crush on him, why I probably do. The moonlight catching the edge of his wavy hair, the scar on his cheek from a bike accident. And sure, maybe it’s because he’s the only person I’m capable of holding a conversation with these days, but that’s how it’s supposed to work, right? That’s how it goes?

Not that it matters. Because I’m a boy. I’m not out yet, but that changes tomorrow. So.

“I thought you might want it,” I say, so he can’t get a word in before me. My hands wind the shoelace around my wrist, unwind it, wind it up again. “Proof, I mean.”

“Proof of what?” Cooper says. “We have a death certificate and a gravestone. I don’t know what else you need.”

I grit my teeth. Yes, Mrs. O’Brien has been dead for years. Mr. O’Brien can’t leave his apartment half the time, Dad can’t walk right no more, and last I heard Dallas Foster had recovered from the burns—a miracle if you ask me—but now Dallas is in Charleston and lost our numbers and we don’t talk no more. But that’s not what this is about.

“Just,” I say, “look at the pictures.”

“I did.”

I pull the photocopies from his pocket—“Jesus!” Cooper says—and slap them into his hand. Ain’t enough light to see by, so I hold up my phone to use my lock screen as a lamp.

“There. Look.”

Cooper sucks in air through his teeth and takes the photocopies. He’s shaking.

Dad took these photos as the car burned, seconds after he’d pulled himself off the twisted crunch of metal that’d impaled him a dozen times from hip to calf. Bleeding out on a cliffside in the middle of the night, trying to save a child seconds from burning to death, holding back a friend whose wife had immolated in the back seat. In the second photo, there’s the edge of Mrs. O’Brien’s body, slumped over, swallowed by flames.

Dad took the pictures because Sheriff Davies was there. At the top of the cliff. By the wrecked guardrail.

Because Sheriff Davies ran them off the road.

And in these photos, in the firelight, you can see him.

“There he is,” I whisper. “We got photos. We got proof. That he did it.” Cooper’s throat bobs and his fingers dent the paper. “And—I don’t know. We could do something with this, right? If you want to give it to your dad? I think Dallas’s brother and sister-in-law came back to Pearson too, bought out some old building, and if…” I nod back through the trees, up to town. “If we want to give it to some grown-ups. See what they can do.”

“Sister-in-law?” Cooper asks, even though he’s barely there. Just staring at his mom in those pictures. “Ms. Amber?”

“Yeah.”

He breathes in shakily. “You think they could do something?”

I don’t say, I think Dad wants to run for county commission again, and maybe some blackmail is in order, to keep the sheriff away from him. I don’t say, I think it’d help your dad if he puts himself towards something again, if he wants to get involved too. I don’t say, I know this is dangerous, but we have to try.

“I think so,” I say. “We can’t recall the election, but we can make his life hell.”

Did you know that Sheriff Davies’s great-grandfather is the one that hammered the railroad spike into Saint Abernathy’s mouth?

Cooper slowly takes the photocopies. Folds them tight. Tries to breathe.

I lean forward, holding my shoelace tight.

What are you thinking, O’Brien?

And then feet crash through the underbrush and I jerk away from Cooper like he burns, because the sheriff’s son is standing on the riverbank with his friends and laughing, “Shit, sorry, didn’t mean to interrupt the lovebirds.”

CHAPTER

3

Freshman year, Noah Davies and his friends—Eddie Ruckle and Paul Miller—killed Nancy Adams’s dog because Noah asked her to homecoming and, wouldn’t you know it, the bitch said no.

Eddie filmed it the same way he filmed his little stepsister in the shower that one time: breathing hard, struggling to keep the subject in frame. Noah had a Milk-Bone in one hand and a hunting knife in the other. Paul held the dog down while it screamed. And the morning Nancy found the corpse on her front porch, you could hear her clear across the holler. I thought it was a cougar, or another car crash. For a moment, eating breakfast hunched over the kitchen sink, I could have been convinced the world was ending.

The video got posted wherever it’d do the most collateral damage. Facebook, forums, group chats. The kids in Twist Creek County have a fight-or-flight response to the sound of shoes squeaking on wet grass. As for Nancy, she left town the next week. Rumor says Noah cornered her in a bathroom, said he’d do the same to her if she didn’t shape up, and she decided running was a better option.

That’s how it goes around here. Eddie is a wet-rat-looking son of a bitch, a bestgore.com fanboy if I’ve ever seen one. Paul never says much, always hangs back, but his family runs a wild game processing business that’ll take any animal out of season as long as you pay the right price. Then Noah—well, Noah’s gonna be a cop when he graduates. Get elected sheriff when his dad can’t keep up the gig, because that’s how it works.

I remember, distantly, that Twist Creek County don’t got ambulances no more. You gotta call EMTs down from Maryland these days.

“For what it’s worth,” Noah says, stepping towards us and fully out of the distant light of the bonfire, “y’all make a cute couple.”

“We’re not—” I start.

Cooper interrupts. “What do you want?”

It ain’t biologically possible, but I swear Noah’s eyes catch the moonlight and shine like a coyote. He’s grinning and showing all this teeth. “Thought I heard something, so figured I’d check up on everybody.” Noah gestures at Cooper. Eddie and Paul follow his finger, two pairs of eyes snapping into place. “What’s that you got there?”

Cooper puts the photocopies in his pocket. “Some old homework. Was gonna burn it.” Good move. We can afford to lose one if it means avoiding suspicion. “Got distracted is all.”

For some reason, Eddie finds this hilarious. “By Abernathy? Really?” He lurches forward, peering over Noah’s shoulder. “Nothing much at if you ask me. Those ain’t tits, those are mosquito bites.”

“Shut the fuck up,” Cooper says.

I don’t like when Eddie looks at me. Like he’s trying to find the best place to split me open, like I’m that dog. Or at least, he’s looking for the best angle to watch from.

“All right boys, all right,” Noah says. “No need for this. Just doing my rounds, not trying to start fights.” Rounds, like he’s already a cop. He’s always done this; sticking his nose where it don’t belong, hissing like a snake in a burrow. Eddie groans. Paul says nothing. He ain’t even paying attention to us, instead looking into the woods, the sort of thing Mamaw and Papaw told me never to do around here. Noah continues: “Glad to hear you’re good, O’Brien. Abernathy? You good?”

Stop talking to me. “I’m good.”

Does he feel the weight of it every time we cross paths? A hundred years of bloodshed? Dad, left to bleed out on the side of the road. Papaw’s brother shot dead in his truck forty years ago and Papaw tracking down Davies’s uncle to do the same. My great-grandmother Lucille locking her daddy’s killer in the old post office and burning it down. The railroad spike through Saint Abernathy’s mouth.

Does he feel it too, or is this all some game to him?

“I was, uh,” I say, “about to head out.”

Noah says, “Wait. Before you do.” He clicks his tongue to make sure my attention is solidly on him, but how could it be anywhere else? “I heard Mr. Abernathy swung by town hall a few days ago. Asked some questions. Any clue why?”

I have the sudden urge to vomit, but what comes out is, “No idea. Tax bill, probably.”

Noah hums. “Shame y’all are so behind on those.”

“Yeah, well, the accident kinda put us out an income, so.” That’s only half a lie—Uncle Rodney has Dad working under the table at the garage, but it barely covers groceries. These days it’s mainly Mom at the nursing home and my dishwashing gig at Big Kelly’s. “Can only do so much.”

Noah nods as if in sympathy. “It’ll do that. Get on, then. And make it quick. Don’t want a little girl in the woods alone after dark.”

Little girl. It stings.

“Want me to come with you?” Cooper asks.

I glance between Cooper and the boys. I don’t want to be alone, but I also don’t want Noah to think we’re doing anything we shouldn’t. “I’ll be fine.”

“Be safe,” Eddie giggles, giving me a little wave.

Cooper swallows hard. He don’t like this. I don’t like it either, but I force a smile and tap my pocket. Think about the photos, O’Brien. Show your dad. It’s been five years since our parents tried to save Twist Creek County, I know, but five years is enough time to do it better this go-round.

Just let me get back home in one piece—and past my parents, because lord knows if they find out I ran into Noah Davies at a late-night party, I’m in deep shit.

I give them all a nod in goodbye, because maybe being polite will keep me a little safer, and slip past the tree line.

Navigating the woods ain’t too hard. All I have to do is keep going straight and I’ll hit the road eventually; that road will be McLachlan’s Main Street, and home’s right up the mountain from there. I can see a streetlight or two through the trees if I really try. Cooper, Dallas, and I used to play down here all the time.

Still. I can’t breathe until the boys are out of earshot. My mouth is dry and my skin is too tight. I swear to god, even the air around Noah and them is rotten. I unwind the shoelace from my wrist, where it’s left an indent in the skin, and jam it back in my mouth, teeth grinding against the one plastic aglet I haven’t ripped off already. Sure, it’s a little gross, but I wash it every few days, and it’s better than picking at my scalp. I do that when I’m stressed. Chew on stuff or tear up my skin until it bleeds. It’s a compulsion. It calms me down, I think.

The plastic gives way, cracking in my mouth. I grab a branch and haul myself up over a dirt ledge.

I pause here. Lean against a tree, squeeze my eyes shut and try to breathe. The shoelace dangles from my mouth. My chest hurts and my head might as well be stuffed with cotton, my stomach turning. Breathe, Miles. C’mon.

It messes with you, growing up like this. Knowing someone wants to hurt you for the hell of it. My parents tried to keep the feud from me because they’re good parents—like they tried to hide the money troubles, and the year Dad couldn’t get off OxyContin, and the gun hidden in the safe under the nightstand. But it’s harder to hide the rules. Don’t go nowhere without an adult, even if Cooper or Dallas are there. If we call the house, you better be there to pick up. Stay away from the Davieses. Stay away from Ruckle and Miller. Keep your eyes down, don’t cause trouble, and above all, don’t get in grown folks’ business, because grown folks’ business gets people hurt.

Only problem is, Mom and Dad raised a smart kid. I figured it out. I have pictures of our family going back a hundred years, copies of every birth certificate and land deed and newspaper clipping. I have Dad’s medical bills and the photos he thinks he locked up for good. I have the papers from when he and Mrs. O’Brien filed to run for county commission, when Ms. Amber ran for county assessor, when Mr. O’Brien ran for sheriff. I know every damn thing about this family and everyone that’s ever touched it.

And you think I stopped there? I printed out a copy of The Communist Manifesto five pages at a time on the school computers. I devoured Kropotkin and Engels, every preserved piece of John Brown’s work. Did you know West Virginia broke off from Virginia in refusal to join the Confederacy? Did you know socialists armed the miners of Twist Creek County?

That’s what I call myself. A socialist. Because my great-great-grandfather was, and he was a socialist for a damn reason.

I have to keep going. Get out of these trees, get home to Lady. Ugh, I really should’ve let her come with me. I’ll let her sleep in my bed tonight so I’m not alone, and then I just have to wait for morning. For my parents to find the email. We’ll see where we go from there.

But I pick up my head, and in front of me—

A light flicks on.

It’s so bright it hurts. I instinctively close my eyes against it, stopping in my tracks to hold up a hand. My first thought is almost nonsense: Is someone spotlighting deer? So close to town, so far out of season?

But then: “Hey, Sadie.”

My vision clears as I get used to the light, blinking desperately to make sense of what’s in front of me.

Eddie’s there. Between the trees. A flashlight in one hand and his phone in the other—horizontal, like he’s recording.

He’s recording.

I take one step back. Another. My heel hits the ledge I’d climbed over, dirt raining down. How did they get ahead of me? “Eddie. I don’t—” My voice cracks. Usually when I put emotion into my voice, I’m doing it on purpose, I’m actively putting it on to get a point across, but these words shatter before I can stop them. “Cooper and me, we weren’t doing nothing, I swear. We were talking about graduation. Turn that off. Please.”

Behind Eddie, something moves. I make out Noah’s face. Paul’s.

“Weren’t doing nothing,” Noah repeats slowly. He pulls a piece of paper from his pocket, unfolding it carefully. “You know, I was gonna ignore all that commie shit you were reading at school, because really, what’s a girl like you gonna do? But . . .”

He whistles and holds up a set of photocopies.

“Gotta admit,” he says, “these ain’t doing you any favors.”

Oh.

Where did he get those? There were three copies before I left the house, so he couldn’t have broken in and stolen one. Did he take it from Cooper? But Cooper didn’t text me, or yell for me, or anything like that. Was Noah in the library when I made them, sneaking in behind me to print out a copy for himself? Has he been following me?

“I’m not—” I stammer. “It’s—”

But there’s no way to deny what those photos are of.

“Poor thing,” Eddie giggles. His voice is wet and high. “If it makes you feel better, we’re giving you a head start. Ain’t no fun if it’s just a slaughter.”

My brain is almost calm as it sorts through everything I’m not gonna get to see tomorrow. Lady. Mom and Dad. Mamaw and Papaw. I left that coming-out email on the desktop, and now they’re going to have to read it without me. I shouldn’t have sent it. I’m not the child you thought I was, sorry I died in the woods at a party. At least I said I love you before I left the house? At least I signed the email with a heart emoji, so they know?

For the first time tonight, Paul speaks, and all he says is, “Run.”

There’s no time to argue. No time to plead or beg. A deer can’t negotiate with a bullet once it’s been fired.

I run.

CHAPTER

4

I don’t remember what they did.

CHAPTER

5

Only that there was a lot of blood, and all of it was mine.

CHAPTER

6

Then nothing.

CHAPTER

7

A moment later—or maybe it’s only a moment to me, god knows how long it’s really been, I don’t know I don’t know—I’m awake and screaming.

It hurts. My throat is swollen shut like there’s a railroad spike jammed in my mouth and I taste copper and there’s something in my arm. I want it out. I grab it. Rip it free. Blood spills out from a vein, sputters towards my wrist as I sit up, grab my face, find bandages and sharp spikes of pain. There’s a shrieking beep beep beep and it keeps getting faster. I can’t breathe. I can’t—

Hands grab my shoulders and push me against cheap sheets. Hold me down. I push back but they shove desperately, pleading. Please.

I stop. Drag down a single breath. Beg my lungs to work again.

Distantly, the working sounds of a hospital. Everything I memorized after the accident. An EKG. The rustling of notes and paper. Someone’s voice rising out in the hall. And the smell: disinfectant, bleach, alcohol. The overwhelming medical cleanliness that reminds me of visiting Mom at work, the nursing home scent clinging to her scrubs.

And wheezing. The wet, fleshy churn-sound of choking.

I force my eyes to focus. To make sense of the blurry mess in front of me. Because there’s a man—not a nurse, not Dad, a man in a stained shirt and red fabric around his neck—holding me down. Looming over my hospital bed. Lean and sharp-mouthed, almost cruel-looking. There’s dirty blond hair hanging over his eyes and coal dust in the lines of his face.

No, that’s not right. The mines haven’t operated in Twist Creek County for decades. But he’s here and he’s struggling to breathe just like me. Wheezing desperately.

I’m not scared, because I know him.

I want to say it. I know you. I know you from somewhere.

Who are you?

Before I manage to ask, a nurse bursts into the room. “Oh shit,” she says. She grabs my arm. I realize I ripped out my IV. The medical tape hangs limply in the crook of my elbow, the plastic tubing lying coiled in my bedsheets. I’m suddenly woozy. My own IV? I did that? “She’s awake!”

I try to point to him, ask why this man is here, who he is, but he’s gone.

CHAPTER

8

Mom and Dad hover by my bed—Mom sipping her coffee slow to give her hands something to do, Dad bracing himself on her chair because he refuses to use his cane—while the doctor does whatever doctors do after someone barely survives getting beaten to death. She’s in a rush, because of course she is. Southern Memorial Hospital is understaffed. There’s a scare piece in the local paper, Southern Memorial at Risk of Closing, every month at this point. I won’t believe it until I see the doors boarded up.

The doctor makes one last note and tucks the clipboard under her arm. “She’s fine. Be back in a bit. And get that IV back in, Christ.”

The nurse winces as the doctor leaves. “Sorry.”

“I can do the IV,” Mom says. “If you’re busy.”

“You will not.”

It takes a minute to recognize her, but my nurse is Amanda. She used to work with Mom at the nursing home before she got her degree. We like Amanda—she’s a tall, shrewd-faced woman who despises small talk and tells us things to our faces.

She picks up my (cleaned and bandaged) arm with a well-meaning glare.

“And you, missy,” she says, “are not going to rip this out again. You’re in bad enough shape as it is.”

She’s right. My entire head is swollen and thick; when I touch my face, it’s all bandages and splints. Several of my fingers are taped together and my arms are a scatterplot of bruises, scrapes, gauze. I think the nail of my pinkie finger is—is it gone? My chest hurts every time I breathe in. Everything hurts.

And I’m seeing things too. Maybe I have a concussion to boot, some kind of traumatic brain injury.

“I won’t,” I say, and Amanda laughs as she readies the replacement IV.

From the corner of my eye, I see Dad cringe at the needle. He never likes to look at people, but now he’s staring blatantly at the ground, fidgeting with the drawstring of his pants.

“Dad,” I say carefully. “You ain’t gotta be here for this.”

Dad slouches. “I’m fine.”

The accident changed him. When I compare him to the diagnostic criteria for PTSD in the DSM-5 which I’ve done at least twice, he hits all the beats. Not nearly as bad as he used to be, but bad enough: refusing to drive, struggling to sleep, flinching like a frightened rabbit if you burn something in the kitchen. This is the first time he’s been inside a hospital in five years and he’s clutching Mom’s shirt like a lifeline. He’s playing it off as his hip being bad, but I can tell the difference. It’s in how he distributes his weight.

It’s weird to call it an “accident,” but that’s what Davies calls it, so it’s the word we have to use.

“You’re not fine,” I say. Mom sighs. “Go outside. You’re about to puke.”

Amanda hesitates with the IV cannula in hand. Dad glances from Mom to me, then grabs my head in his big hand. He presses his mouth to my forehead carefully, to avoid whatever’s going on up there. Stitches? I don’t know. It’s clumsy, and he hits something that hurts, but I don’t care. I slump awkwardly against him. He smells like the same brand of aftershave he’s used since I was four.

And then, I remember: the email.

The coming-out email. The damn thing I left on the computer for them to find when I didn’t come home in the morning. They have to have read it, right? Or did they miss it in the confusion, when they learned something happened to me?

“Can’t get anything over on you, can I?” Dad says, wholly ignorant of the crisis I’m swallowing down. “Love you.”

“Love you,” I say. My voice is perfectly level. I have emotions, obviously, but sometimes it’s a bit of work to show them, and right now it’s best if I don’t.

Dad limps out of the hospital room. He thinks I can’t see it when he scrubs a hand over his face, looking as haggard as he did the day after the accident. I huddle against the flat pillow. I want my shoelace. Maybe I should ask for it back, if they have it. If I didn’t drop it on the forest floor. In the meantime, I fidget with the plastic bracelet around my wrist, the one with my legal (incorrect) name and identification barcode.

Amanda shoots Mom a glance over the hospital bed once Dad is out of earshot. “I’m gonna get him using that cane one way or another.”

“Good luck,” Mom says.

“His hip’s fucked.” Amanda offers me a flat smile. “Pardon my French.”

“I don’t give a shit,” I say. That gets Mom to laugh. “Can you do my IV already?”

Amanda says, “As you wish,” and takes my hand to put the IV in my wrist, since apparently I busted the vein in the crook of my arm. I wince as she pushes the needle in. “You gave us a hell of a scare, you know.”

With most people, that sort of statement means they’re trying to get an apology, but I’m not going to apologize for almost dying, and also I don’t think Amanda would be so indirect. I sniff and a shock of pain shoots up my face. “What’s the damage? Can I see my chart?”

Amanda gives me a look. “Honey—”

I realize I forgot to be polite. “Please.”

Amanda turns to Mom for direction. I know what the answer’s gonna be before she so much as moves. We’re the same kind of person. We need all the information, and we need it upfront.

Mom waves her consent.

“Right,” Amanda says, turning my electronic health record towards her. “The O’Brien boy brought you in”—Cooper?—“and you were real bad. In shock, losing more blood than I thought we could replace. Fractured ribs, internal hemorrhaging, broken orbital socket, broken nose, broken fingers. Thought you had a skull fracture too, but it was just a flesh wound, thank god.” Another flat smile. “Plus a hundred little contusions and more bruises than you can shake a stick at. What a way to start summer vacation.”

I run my tongue over my front teeth and find a piece of enamel missing, right at the front. I’d forgotten that the party was only hours after class let out for the summer. There’d been no signing yearbooks or hanging out in the gym for me. I’d spent my last day of junior year swiping cupcakes from my auto shop classroom and helping the librarian sort books.

“But I ain’t dying?” I say.

“You ain’t dying,” Amanda confirms. “Not anymore.”

Amanda does her job: checks my vitals, changes my bandages, shows me where I’ve been hurt. She says I’ve been in and out for a day or so, but it’s no surprise I can’t remember it. She lets me touch the stitches on the shaved part of my scalp and carefully pulls aside my hospital gown to show me where surgeons cut me open. Apparently one of my ribs punctured something, requiring an emergency operation. I try to imagine myself in the operating room, cracked open so they can yank a jagged piece of bone from my lung, or—what else would a rib hit? My liver? “Not much we can do for the bones themselves,” she admits. “We put them back in place with some nice pieces of metal, though. You’ll be setting off detectors for the rest of your life.”

All of that, I take fine. The boot-shaped bruises on my stomach and legs, fine. The medical bills I’m definitely racking up, fine. It’s fine. But a sick thought crawls up the back of my throat.

I glance up at Amanda. “Was I . . . ?”

I can’t say the words, but I don’t have to. Beside me, Mom makes a broken noise. I don’t know if—if something like that happened. No matter how much I try to recall, it’s like my head is stuffed full of gauze. Just dark leaves and the taste of metal in my mouth.

Amanda goes pale. “Did you remember something?”

“No,” I admit. “But . . .”

“We can run a kit if you want.”

Mom cuts in. “Those are so invasive.”

And they cost money. I think. I’m not sure.

“We don’t have to,” I say quickly. “It’s fine. Can I—can I talk to my mom?”

Amanda nods, changing the topic as deftly as a nurse is trained to. “Of course. Press this button if you need me. And here’s your painkillers. Don’t be a martyr about it, okay? If it hurts, take them.”

She places a single pill, which I immediately recognize as OxyContin, in a cup by the side of my bed, along with a glass of water. When she scans my ID barcode to add the cost of it to my patient record—at a 500 percent markup—she winces in apology, and then she’s gone.

I push the pill towards Mom. “It’s, um.”

Mom pulls a face. There are bags under her eyes, and her nose is bright red despite the stoic set to her mouth. You can use her hair as a barometer for how bad a situation’s gotten—it’s fallen out of its bun and she ain’t bothered to fix it, which hasn’t happened since Dad was in the hospital. She don’t look people in the eye, the same way I don’t, the same way Dad don’t. Mom has a trick, though. She watches people’s mouths when they speak, or a little spot at the corner of their eye. It’s close enough to eye contact that most people can’t tell the difference. Now that I know, I can tell when she’s doing it to me, but that’s fine because I’m doing the same.

Mom takes the cup, inspects the pill, hands it back. “I’ll keep an eye on you. We know what not to do this time.”

She’s technically right, but it seems optimistic. I swallow the painkiller anyway and show my tongue to prove it went down; a holdover from elementary school, when I’d spit out any medicine they tried to give me.

“Guess they couldn’t hook me up to a morphine drip,” I say.

“That’s for people who are dying,” Mom says, even though I don’t think that’s right. “I would ask how you’re doing, but that feels mean.”

“I’m as good as I can be, considering.”

She splutters a laugh. Despite the fact that she’s a mess, she’s doing her best to stay as poised as possible. That’s Mom for you. She ain’t from around here—she grew up in Maryland—but she’s as tough and strong as any mountain woman. She has to be, marrying an Abernathy the way she did.

“What happened?” Mom says.

I don’t answer. No response seems right. When I think about it for too long, I want to collapse into a heap of tears and panic, but my sense of decorum constantly outweighs what I actually want. The idea of losing it is embarrassing, so I simply don’t.

“Was it the sheriff?” Mom asks.

“No,” I say, and it’s the truth. It wasn’t him, technically. “And I don’t need Dad thinking it was. Okay? It wasn’t him.”

It don’t seem like she believes me, but she says, “Okay.”

I don’t want to talk about this anymore. I grasp for straws—How’s Lady? How’s Cooper, or Mamaw and Papaw? Have you seen a strange man who can’t talk?—and land on . . .

“Did you get the email?” I ask.

Mom makes a forcibly nonchalant noise. “Email?”

It’s clear she knows what I mean, but I play along with the feigned ignorance because it’s the expected thing to do. “The one I sent before.” My head wobbles vaguely, implying the obvious. “You know.”

Mom takes a deep breath.

She hesitates.

“That’s not,” she starts, then reconsiders. “I mean, yes. We got it.”

I can’t pinpoint her tone. “Oh.”

“And we read it. While you were in surgery.”

The email was a long one. A good one, if you ask me, with a curated list of hyperlinks and an extensive FAQ section. Yes, I know I’m a boy, I figured it out late last year; no, I’m not a masculine woman, I already tried that; yes, I’m nervous too. An email seemed like the easiest way to do things. I’ve always preferred writing things to saying them out loud. I wanted to head off every question, provide every detail ahead of time, in hopes that this would be as simple as possible.

“It’s a lot to take in,” Mom says.

“I know,” I say. “I said that. In the email. This is a lot, and you don’t gotta get it right away—”

“And I don’t think it’s a conversation we’re ready to have right now.”

My stomach drops. “Mom.”

“A lot of bad shit just happened, and it’s a lot to process. I’d rather us take it one thing at a time.” There’s no smile on her face, no softness at all. She’s approaching this like I’m an argumentative resident at the nursing home, like I’m Marie Jo insisting she don’t need a shower. “There’s a lot we’ll have to talk about.”

“There’s nothing to talk about,” I whisper. “I said everything already.”

I don’t talk back to my parents. They’re reasonable people, and we’re all the same kind of off