Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

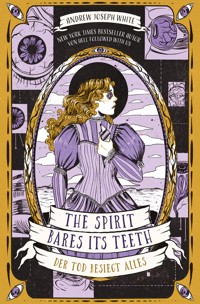

This instant New York Times bestseller is a visceral Victorian gothic horror of a young autistic trans boy who can commune with spirits, forced into a haunted sanitorium. Mors vincit omnia. Death conquers all. London, 1883. The Veil between the living and dead has thinned. Violet-eyed mediums commune with spirits under the watchful eye of the Royal Speaker Society, and sixteen-year-old Silas Bell would rather rip out his violet eyes than become an obedient Speaker wife. According to Mother, he'll be married by the end of the year. It doesn't matter that he's needed a decade of tutors to hide his autism; that he practices surgery on slaughtered pigs; that he is a boy, not the girl the world insists on seeing. After a failed attempt to escape an arranged marriage, Silas is diagnosed with Veil sickness—a mysterious disease sending violet-eyed women into madness—and shipped away to Braxton's Sanitorium and Finishing School. The facility is cold, the instructors merciless, and the students either bloom into eligible wives or disappear. So when the ghosts of missing students start begging Silas for help, he decides to reach into Braxton's innards and expose its rotten guts to the world—as long as the school doesn't break him first.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 465

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Letter from the Author

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

One Year Later

Note on Historical Accuracy and the Representation of Medical Experimentation

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Available from Andrew Joseph Whiteand Daphne Press

Hell Followed with Us

The Spirit Bares Its Teeth

Compound Fracture

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

First published in the UK in 2024 by Daphne Press

www.daphnepress.com

Copyright © 2023 by Andrew Joseph White

Cover artwork by Evangeline Gallagher © Peachtree Teen

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher.

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-83784-072-4

eBook ISBN: 978-1-83784-073-1

1

For the kids with open woundsthey’re still learning to stitch closed

—A. J. W.

LETTER FROM THE AUTHOR

One of the cruel injustices of the world is that survival hurts sometimes. Open-heart surgery, for example, looks a lot like murder. Amputation before the advent of proper anesthesia was just a bone saw and a rag to bite. On that note, I will make this clear: The Spirit Bares Its Teeth contains transphobia, ableism, graphic violence, sexual assault, discussions of forced pregnancy and miscarriage, mentions of suicidal ideation, and extensive medical gore.

But I will also make it clear that this book is not a necessary procedure. You don’t have to endure it. You can get off the operating table and walk away at any time. I won’t blame you.

For those still reading—do you have a rag to bite?—I want to make note of some context. Ghosts and mediums and alternate histories aside, The Spirit Bares Its Teeth was inspired by Victorian England’s sordid history of labeling certain people “ill” or “other” to justify cruelty against them. Threats of violence enforced strict social norms, often targeting women, queer and disabled people, and other marginalized folks. I have included another note about these realities at the end of the book, including some that this book does not cover. True history is often much more heartbreaking than any horror novel can depict.

So, if nothing else, I hope this story means something to you. I hope the scalpel is kind to you. I hope your sutures heal clean. You deserve that much; we all do.

Yours,

Andrew

CHAPTER

1

The last time I spoke to my brother was six months ago. I remember the date exactly: the twenty-second of April, 1883. How could I not? It’s burned into me like a cauterized wound, an artery seared shut to keep from bleeding out.

It was his wedding, and I was on the edge of hysterics.

I wasn’t being difficult on purpose. I wasn’t, I swear. I never mean to be, no matter what Mother and Father say. I’d even promised it would be a good day. I wouldn’t let the too-tight corset send me into a fit, I wouldn’t tap, I wouldn’t fidget, and I certainly wouldn’t wince at the church organ’s high notes. I would be so perfect that my parents wouldn’t have a reason to so much as look at me.

And why shouldn’t it have been a good day? It was my brother’s wedding. He’d just returned to London after a few months teaching surgery in Bristol, and all I wanted was to hang off his arm and chatter about articles in the latest Edinburgh Medical Journal. He would tell me about his new research and the grossest thing he’d seen after cutting someone open. He’d quiz me as he fixed his hair before the ceremony. “Name all the bones of the hand,” he’d say. “You have been studying your anatomy, haven’t you?”

It would be a good day. I’d promised.

But that was easy to promise in the safety of my room when the day had not yet started. It was another to walk into St. John’s after Mother and Father had spent the carriage ride informing me I’d be married by the new year.

“It’s time,” Mother said, taking my hand and squeezing—putting too much pressure on the metacarpals, the proximal phalanges. “Sixteen is the perfect age for a girl as pretty as you.”

What she meant was, “For a girl with eyes like yours.” Also, it wasn’t. The legal marriageable age was, and still is, twenty-one, but the laws of England and the Church have never stopped the Speakers from taking what they want. And it was clear what they wanted was me.

It was like the ceremony became a fatal allergen. While Father talked with a colleague between the pews and Mother cooed over her friends’ dresses, I dug my fingers into my neck to ensure my trachea hadn’t swollen. The organist hunched over the keys and played a single note that hit my eardrums like a needle. Too many people talked at once. Too loud, too crowded, too warm. The heel of my shoe clicked against the floor in a nervous skitter. Tap tap tap tap.

Father grabbed my arm, lowered his voice. “Stop that. The thing you’re doing with your foot, stop it.”

I stopped. “Sorry.”

On a good day, I could stomach big events like this. Parties, festivals, fancy dinners. Sometimes I even convinced myself I liked them, when George was there to protect me. But that’s only because a legion of expensive tutors had trained me to. They’d molded me from a strange, feral child into an obedient daughter who sat with her feet tucked daintily and never spoke out of turn. So, yes. Maybe, if it had been a good day, I could have done it. But good days had suddenly become impossible.

In the crowd, I slipped away.

Sometimes I pretend my fear is a little rabbit in my chest. It’s the sort of rabbit my brother’s school tests their techniques on, with grey fur and dark eyes, and it hides underneath my sternum beside the heart.

Mother and Father are going to do this to you, it reminded me. I pressed a hand against my chest as I searched the pews to no avail. The church was long, with stained glass stretching up like translucent membranes. And when they do, you’ll cut yourself open. You’ll pull out your insides. You promised.

I stepped out into the vestibule, and after all this time, there he was. My brother with his groomsmen, friends from university I’d never met. Stealing a drink from a flask. Swinging his arms, trying to get blood to his fingers. Bristol had changed him. Or maybe he’d just matured while I wasn’t there to see it, and it’d be better if I turned him inside out and sewed him up in reverse so I no longer had to watch him age. At least, now that he was back, he’d be serving the local hospitals and nearby villages, and he wouldn’t be so far away from me. Nothing all the way out at the coast, not anymore.

I said, barely loud enough to hear, “George?”

My brother met my eyes, and his first words to me in months were, “That’s the dress you picked?”

Right. I’d tried awfully hard to forget what I was wearing. The corset was specifically made to accentuate curves and the dress was gaudy, with a big rump of a bustle as was the fashion. Or Mother’s idea of the fashion. I’d studied diagrams from George’s notes of how tightlacing corsets could deform bones and internal organs, memorized them until I could draw them on the church floor with charcoal. Flesh and bone make more sense to me than the people they add up to.

“It was Mother’s idea,” I said plainly, resisting the urge to chew a hangnail. “May I speak to you? For just a second?”

George flashed a grin at his groomsmen. “Sorry, lads. The sister’s more important than you lot.”

So he broke away from the flock, even as his friends groused and jabbed their elbows into his ribs—and then he led me to a quiet corner in the back of the sanctuary. Away from the people and the noise.

Without Father to snap at me, I couldn’t stop fidgeting. My hands wrung awkwardly at my stomach, and I bit my cheek until I tasted blood.

It’s pathetic you ever thought you’d avoid this, the rabbit said.

George got my attention by putting a hand in front of my face. “In,” he said. I scrambled to follow his instructions, breathed in. “Out.” I breathed out. “There we go. It’s okay. I’m here.”

As soon as you were born with a womb, you were fucked.

I couldn’t take it anymore. The mask I’d built to be the perfect daughter cracked. The stitches popped. I began to cry.

George said, “Oh, Silas.” My name. My real name. It’d been so long since someone called me my real name. I clamped a hand to my lips to stifle an embarrassing gasp. “Use your words,” George said. “Tell me what’s wrong.”

I didn’t mean to do this at his wedding. I didn’t do it on purpose. I didn’t, I swear.

I said, “I need to get out of that house. It’s happening. Soon.” I started to rock back and forth. George put a hand on my shoulder to hold me still, but I pushed him away. I had to move. I’d scream if I couldn’t move. “No. Don’t. Please don’t. I just—I don’t know, I don’t know what to do.”

“Silas,” George said.

“If I get away from them, I could buy a little more time.” Could I, though? Or was I just desperate? “Don’t leave me alone with them, please—”

“Silas.”

I forced myself to look at him. My chest hitched. “What?”

Then, one of the groomsmen, leaning out to the pews, bellowed: “The bride has arrived!”

“Shit,” George said. “Already?”

“Wait.” I grabbed for his sleeve. No, he couldn’t walk away now, he couldn’t. “George, please.”

But he was backing up, peeling me from his arm. When I remember this moment months later, I recall his pained expression, the worry wrinkling his face, but I don’t know if it was actually there. I cannot convince myself I hadn’t created it in the weeks that followed.

“We can talk about this later,” George said. “Okay? Sit, before someone comes looking for you.” Nausea climbed up my throat and threatened to spill onto my tongue. “Afterwards. I swear.”

He walked away.

I stared after him. Still shivering. Still struggling for air.

What else was I to do except what I was told? I never learned how to do anything else.

I scrubbed my eyes dry and found my place with our parents. Mother smiled, holding me by the shoulder the way surgeons used to hold down patients before anesthesia. “How is George doing?” she asked me, and I said, “He’s well.” The organist ambled into a slow, lovely song, and the sun shone through stained glass in a beam of rainbows. George stood at the end of the aisle. He met my gaze and smiled. I smiled back. It wavered.

The bride herself, when she walked in on her father’s arm, was tall, with honey-colored hair. She was not the most beautiful woman in the empire, but she didn’t have to be. She radiated such kindness that it was as if she were made of gold.

But.

She had violet eyes.

And a silver Speaker ring on her little finger.

The rabbit said, Soon, that will be you.

When I was younger—ten, I think, or maybe eleven—I dreamed of amputating my eyes. It seemed easy. Stick your thumb in the socket, work it behind the eyeball, and take it out, pop, like the cork in a bottle of wine. If they were gone, I reasoned, the Royal Speaker Society would leave me be. They came over every Sunday to savor cups of Mother’s tea, talk with Father about ghosts and spirit-work and economic ventures in India, and calculate the likelihood of their children having violet eyes if they had those children with me. “You’ve never played with a ghost, have you?” a Speaker said once, teasing my sleeve. “Because you know what happens to little girls who play with ghosts.”

And it has never stopped. It has only gotten worse, louder and louder as I grew into my chest and hips. Now they kiss my knuckles and run their hands through my hair. They wonder about boys I’ve been with and offer ungodly sums of money for my hand in marriage.

“Is she lilac, heather, or mauve?” they would ask my mother, holding my jaw to keep my head still. Sometimes they gave me their silver Speaker ring to wear, just to see how I’d look with it one day. “Oh, Mrs. Bell, when will you let her marry?”

Mother would just smile. “Soon.”

I’d grown out of the juvenile fantasy quickly enough. The eyes were a symptom, not the disease. If I wanted to resort to surgery, I’d have to go to the root: a hysterectomy, a total removal of the womb. Until my ability to continue a bloodline is destroyed, these men don’t care how many pieces of myself I hack off—but that doesn’t mean I haven’t popped the eyes out of a slaughtered pig just to feel it.

George’s wife had violet eyes like mine.

He was doing to a girl everything that would be done to me.

I got up from the pew. Mother hissed and reached for me, but I stumbled into the aisle, clamping a hand over my mouth. I slammed out the front doors and collapsed onto the stairs.

I spat stomach acid once, twice, before I vomited.

Father came out behind me, dragging me onto my feet. “What are you doing?” he snarled. “What is wrong with you?”

It will hurt, the rabbit said. It will hurt it will hurt it will hurt.

* * *

George has not been able to face me since.

He knows what he did.