10,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

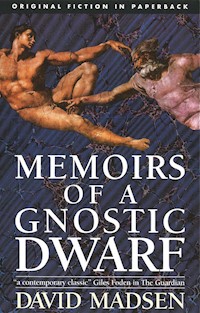

- Herausgeber: Dedalus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

A baroque restaurant novel which merges cannibalism with Platonism

Das E-Book wird angeboten von und wurde mit folgenden Begriffen kategorisiert:

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Dedalus Original Fiction in Paperback

CONFESSIONS OF A FLESH-EATER

David Madsen is the author of three highly acclaimed novels: Memoirs of a Gnostic Dwarf, Confessions of a Flesh-Eater, and A Box of Dreams. David Madsen’s novels have been translated into twelve languages so far.

He is also the author of Orlando Crispe’s Flesh-Eaters Cookbook, an alternative cookbook.

Contents

Title

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter IX

Chapter X

Chapter XI

Copyright

I

The Incarceration of One Unjustly Accused

I did not kill Trogville. No matter what they say, I did not kill him. I introduced a mild narcotic into his glass of whisky; I subsequently stripped him naked, laid him face down on the parquet floor and inserted a courgette into his creamy, quivering anus; but when I quitted his apartment in the Via di Orsoline, he was still very much alive. That was at approximately nine o’clock. At a quarter to midnight he was discovered sprawled out like a stringless puppet, his chest yawning bloodily open, his heart torn out and placed neatly in the palm of his left hand. Now they are saying that I did it. I despised Trogville, I hated and feared him, but I did not kill him.

Allow me to introduce myself: I am Orlando Crispe, otherwise known as Maestro Orlando, and I am a great artist. Indeed, I am an artist of international repute. I am a creator, a demiurge, the image of an aeon, and the primordial material out of which I give birth to the children of my ideation is food. I am in fact a chef. A cook. I am one of the finest cooks in existence; actually, I consider my only rival to be Louis de Beaubois of the Hotel Voltaire in Cairo. I have no time for false modesty – if one is blessed with an extraordinary talent, one should not hesitate to declare it; if I say that I am probably not the best cook in the world I make a liar of myself, and if I say that I am – well, I fall into the immodesty of pride. That is such a short fall; hardly Luciferian.

My culinary studio is a ristorante called Il Giardino di Piaceri, which is situated in a small street just off the Piazza Farnese here in Rome; it possesses a secluded roof garden which I reserve for my very special guests, and it was at a table on this roof garden that I first served my now justly celebrated farfal-line di fegato crudo con salsa di rughetta, burro nero e zenzaro. They told me that such a combination of flavours would never work, but they were all entirely wrong. It was served to Lady Teresa Fallows-Groyne, who married an American painter called Fleebakker, famous for mixing his colours with his own semen.

In my little cell here in Regina Caeli prison, they have provided me with writing materials, and I now pass the long hours of daylight composing these modest excerpta of the anfractuous history of my life; Helmut von Schneider – my dear friend Helmut, who shares my taste for flesh – has promised that he will arrange for private publication as soon as they are completed and edited.

I still blame that corpulent poseur Heinrich Hervé for precipitating the beginning of what was to be my downfall; he it was who tiresomely persisted in urging upon me the task of creating a unique culinary masterpiece, and it was because of him I eventually cooked my very special rissoles, HeinrichProvençale, Andouillettes Hervé and Navarin of Heinrich. Heinrich is (was, I should say) Danish by birth, but for many years lived in Germany, the country of his adoption, where he earned a modest living as a singer. He possessed a very powerful bass-baritone voice, yet one would not, I think, call it beautiful; Eiseneck of Paris Match once referred to him as an overgrown fauvette.

‘These Jews!’ Heinrich thundered, ‘What do they know of art?’ In Germany, force and power have always been preferred to subtlety and style.

Each night on the stroke of eight o’clock he would enter my restaurant, a grotesque fantocchio, and sing until the last diner had paid his bill and departed; he frequently begged, pleaded and commanded me (not necessarily in that order) to hire an accompanist, but this I refused to do – for one thing, my restaurant was not large enough to accommodate comfortably a grand piano. Then he would sit at his table near the kitchen doors – sometimes alone, sometimes with a companion, a young male prostitute picked up for the evening – and devour with gusto the meal I had prepared for him.

‘Bah! I have had Poussin à la Crème at the Chateau Lavise-Bleiberger; in Florence I very nearly died and went to paradise on account of Maestro Louvier’s exquisite sasaties; I have shared Rosettes d’Agneau Parmentier with le Duc d’Aujourdoi at Maison Philippe le Roi; where is your genius, Maestro Orlando? Where is the dish fit for angels that you keep promising me? Why have I not yet tasted the raison d’être of your culinary career?’

So I served him kangaroo steak, but – alas – this was not the ecstasy in flesh which he expected; next I tried grilled côtelettes of gerbil, then otter’s liver, camel’s heart, braised kidneys of polecat, even the testicles of an alsatian dog which – not knowing precisely what he was eating – he consumed with immense gusto but little appreciation; in the end, I became as nauseated by his passion for novelty as my customers were by his purgatorial nightly rendition of Old Man River.

However, I do not wish to anticipate my own story, and since the shadow of Heinrich did not darken the landscape of my life until some years after it had begun to blossom in the springtime of its own proper independence, I had better go back and begin – as they say – at the beginning.

II

The Object of My Desire

My first craving was for flesh. One morning I apparently attempted to bite off a chunk of my mother’s breast as she was feeding me, and she ended up badly ulcerated; after that they put me on the bottle. A psychiatrist here in the prison – an absolute blagueur who sprays me with garlic-flavoured spittle whilst propounding his grotesque theories as to the origins of what he insultingly calls my ‘mania’ – told me that I am obsessed with flesh because I was thus precipitately torn from my mother’s nipple, and that I am in some way trying to rediscover and connect myself to the ‘ultimate source of nourishment’; this is complete and total nonsense, and I think it is Dottore Balletti who is obsessed – with breasts and nipples. His face sometimes assumes a very peculiar expression as he speaks to me of this idée fixe of his. Next time he pays me a visit I must try and see whether he also experiences an erection. Dottore Balletti misses the most significant point and confuses cause with effect: since my trying to bite into my mother’s breast was the reason I was removed from it, it obviously precedes separation from the maternal nipple, and indicates that the craving for flesh is an a priori of my nature.

‘È una furia, quest’ amore per la carne,’ he says.

‘Like all respectable psychiatrists dottore,’ I reply, ‘your greatest talent is for pointing out the obvious. What is not obvious, you ignore, and when there is nothing obvious to point out, you invent it.’

‘Sì, that is my job.’

‘Meat’ (in Italian carne means both flesh and meat) is too particular a term to properly describe the object of my craving; it is flesh which obsesses me, even though in my early years the only kind I ever tasted had once walked on four legs or had wings. Meat is flesh and vice-versa, yet the word ‘flesh’ captures the true flavour, the concentrated extract of the passion which rules me, and I infinitely prefer it. Flesh is my love; meat is what it becomes after I have lavished my creative culinary skill upon it. However, you will find that in the course of my narrative, I use ‘flesh’ and ‘meat’ interchangeably; this is purely for the sake of convenience and variety.

It is the raw material of my creative genius. I chose it (or rather, it chose me) as a painter might choose to work in watercolours or oils, as a composer might choose to specialize in opera; it is a subtle and enigmatic thing, this marriage of man and element, and the most one can say is that it does not occur by means of any purely mortal consideration – rather, there is the operation of what one might call a Higher Will (I borrow this phrase from Schœpenhauer) involved from the very beginning. And who knows when the beginning was? Why was Palestrina enraptured by the human voice? Why was Michelangelo in love with the cool smoothness of marble? Why did Albert Einstein surrender himself to a torrid intellectual affair with the structure of the physical universe? These are unanswerable questions, and they are therefore pointless. My affaire du coeur with flesh is to be located within the same dimension: it serves the high metaphysic of an inscrutable dharma, some inexorable purpose of fate – as I have said, the workings of a Higher Will – which weaves the textures of our existence together into a single fabric. In spite of Balletti’s burblings about breasts and nipples.

My Father: A Harmless Idiot

As you shall soon hear, I was in my early teens when I discovered – in a rather dramatic way – that I did not want to be anything other than a chef, a true master in the culinary arts; indeed, their magic and mystery, their jealously-guarded secrets, their panoply of techniques and tools had intrigued and enchanted me even before I was tall enough to reach the handle on the pantry door. As a child – and without really knowing why – I used to spend hours pottering about in the kitchen: measuring, weighing, sniffing, tasting, concocting; my father, about whom the most charitable thing to be said is that he was a harmless idiot, expended a great deal of energy in trying to persuade me to adopt what he considered to be more congruous interests, such as clockwork trains or football. Only once do I remember him executing an act of genteel violence upon me – for some minor domestic transgression the nature of which now escapes my memory. He beat me on the bare buttocks with a cricket bat; the bat itself he had bought for my eleventh birthday in the vain hope that it might encourage me to take an interest in the game. He made me take down my trousers and undershorts, and lean across the arm of his favourite chair, my face buried in the plump, yielding seat. I still recall the smell of warm, worn leather, enriched by the pungent tang of years of his anal sweat.

He administered three hard thwacks, but I was not hurt. My mother stood behind him, her hands at her throat; she uttered a strange, eldritch shriek each time the bat descended on my naked buttocks. I found this weird ritual mysteriously exhilarating; now, I suppose I would say that it was an erotic experience. After putting aside the bat (and breathing rather heavily) my father then did a strange thing: he reached down underneath my backside and grasped my little scrotum in his hand, exploring it shamelessly, tenderly kneading it with his fingertips.

‘Oh yes, yes, that feels good,’ he murmured. ‘A beautiful pair! Never forget that God gave you balls, Orlando.’

The heat and softness of his hand was intensely pleasurable, as were the firm massaging motions he was making, and I was rather sorry when, after a moment or two, he stopped. That evening alone in my bedroom, I held myself between my legs just as he had held me, squeezing and rubbing gently. It occurs to me as I recall this delectable scena that my father must surely have found the whole experience as erotic as I did, even though neither of us would have been able (for different reasons) to classify it as such. In any case, it was never repeated.

‘Love is a sacred thing,’ he once remarked to me, coming unexpectedly into my room and delivering a preamble to what I supposed was to be a man-to-man chat about the so-called ‘facts of life.’ (Are they not, rather, merely possibilities?) ‘Never be ashamed of what a woman makes you feel inside, Orlando.’

‘Inside what?’

‘That’s how God meant it to be. Never be ashamed of it, and never abuse it; keep yourself clean and pure and manly, and you’ll appreciate the act of love all the more, when the time comes for you to do it.’

Needless to say, I found this bonne-bouche of homespun sexual education excruciatingly embarrassing.

‘I was a virgin on our wedding night,’ he went on, ‘so the joys of it came as a wonderful enlightenment to me. Oh, you’ll be tempted, as we all are – but have the guts to resist, Orlando! Don’t defile your body as some young men do; what could they ever know about the act of love? It’s love that counts, Orlando, not biological urges.’

Then, abruptly switching gear, from mawkish ethical romanticism to clinical dispassion, he continued:

‘The human penis is a marvel of power and precision, Orlando! When a man is fully erect –’

‘I’m rather busy,’ I said. ‘Could we continue this fascinating conversation another time?’

He went out of the room with an expression of crestfallen surprise on his pasty face.

My father left no impression on the malleable texture of my young psyche; today, I can hardly remember the sound of his voice – it was somewhat high-pitched and querulous, I think. Whenever he comes to mind (which is seldom, now) he is but a nebulous figure enmeshed in the windswept nexus of a dark vacuum. I can discern nothing of significance. If Herr Doktor Jung’s esoterically perspicacious observations on this condition are to be believed, the honour of having moulded and shaped me belongs entirely to my mother.

The Queen of My Highgate Childhood

I adored my mother. Psychologically-minded cynics will doubtless cluck and nod their theory-stuffed heads when I say that she was my one true companion and friend as well as my mother, but it is so; there existed between us, from the very beginning it would seem, an osmotic bond which enabled her to intuit and assimilate my every mood, every subtlety of feeling, each summer cloud and autumn shadow that crossed the landscape of my soul, and to respond instantly. Sometimes I did not even have to voice my inner condition – merely to glance at her was knowledge and understanding enough for her capacious, empathetic psyche. Herr Doktor Jung also says that such a mother’s son will turn out to be homosexual for her greater glory, but in my case the good physician’s prognosis is not entirely accurate, for my tastes run to both sexes; the euphuistic carritch of modern sexologists would doubtlessly categorize me as bisexual, but since I have always regarded myself as a subject of celebration rather than an object of psychological inquiry, I prefer not to use this term. Let us just say that ripely-endowed ladies and callipygous young men hold equal appeal for me; this latter may be, I suppose, ex consequenti of the buttock-thwacking administered by my idiot of a father. He cherished the hope that one day I would meet a ‘nice girl’ and want to settle down with her.

‘Don’t you fret Orlando,’ he would say with nauseating paternal confidentiality, ‘Miss Right will come along soon enough.’

I found this prophecy utterly risible; after all, what girl – however ‘nice’ – could possibly live up to the nobility and goodness of my mother? She alone was the only woman in my life. I have made love to a great number of exquisite creatures of both sexes, but I have loved none save my Highgate queen.

My mother herself was extremely beautiful, and I often had cause to wonder what had attracted her to my father; he was certainly not handsome, neither was he graced in character or ability. Once I tried to satisfy my natural curiosity by asking my mother outright, but she did not seem inclined to intimate revelations.

‘There must have been something,’ I said, my hands resting on her knees.

‘Oh yes, yes there was, Orlando.’

‘What?’

‘I hardly think, dear, that this is an appropriate occasion to engage in such a personal conversation. Neither your father nor I are the people we once were. We have changed, Orlando; everybody changes sooner or later, you know. I still love your father. I am not uncontent.’

‘But why do you love him?’ I persisted.

Mother smiled at me: a smile of infinite patience and compassion. She was never angry at me.

‘Oh, Orlando dear, one day I will explain everything to you, and then you will understand.’

But she never did, and so neither did I.

Many years later, under the influence of an extremely fine bottle of Chateau Neuf du Pâpe, I was indiscreet and foolish enough to speak of this to Heinrich Hervé.

‘Maybe he had a twelve-inch cock?’ he said, sneering lasciviously.

And there, dear unknown reader of these confessions, is the measure of the man. As a matter of fact I do not know what the size of his cock was, but if the rest of him was anything to go by, it must surely have been a pallid, uninspiring, wrinkled, nondescript little thing.

In her earlier years my mother had been a successful actress with a repertory company, touring the country with light romantic comedies such as Heartbreak Avenue and Quincey Cavanagh’s Fickle Passions, both of which were highly regarded in their time; however, after she had met my father and he – by some fantastic means the nature of which I could not even begin to guess at – had persuaded her that he was worthy of her love, she relinquished (sacrificed, I would say) her career and settled with him in the house in Highgate where I was conceived, born and grew up. Sometimes, in a nostalgic mood, she would sit me on her knee and speak to me of her golden years on the stage.

‘I was a queen Orlando, a queen! Men would come night after night to the same play, just to see me again. Oh, I was beautiful then.’

‘You still are beautiful!’

‘Alas, I am not as I once was; you must understand that. Then – well – I had my share of admirers, I can tell you. They were heady days. Even the Duke of Manchester … have I ever told you what the Duke said to me after the first night of Love Requited?’

‘Tell me!’

‘He came to the stage door after the performance, and when Marie (my retarded but faithful French dresser) showed him into my dressing-room, I was helpless, completely overcome. I could hardly utter a word! I was inexperienced and nervous, Orlando – what was I to think? The Duke of Manchester! I can still recall how wildly my heart beat in my breast. ‘Madame,’ he said to me, ‘Madame, tonight I have had the privilege and the pleasure to witness one of the finest performances on the northern stage – indeed, of any stage in this country! You will be a great star, Madame. I count myself blessed that I have witnessed your first waxing.’ Then he asked me whether I would do him the honour of dining with him at the Maison du Parc – (it was the most fashionable restaurant in the city at that time, and Sybil Thorndike had once received a proposal of marriage from the Comte de Beauchaise there) – but I had to refuse, for I knew that there was also a Duchess of Manchester, and the possibility of scandal was very real. Besides, I had my career to consider. Oh, Orlando, I refused him! Yes, I refused him, even though he pressed me, and every evening for a month thereafter I received a dozen red roses together with a little card which said: ‘From one who pines beneath the light of a new-born star.’ Oh, Orlando, can you imagine how giddy with pleasure that made me? I, a young and probably foolish girl –’

‘You, foolish?’ I would cry. ‘Oh, mother, I swear that you were born wise!’

Then she would pat me fondly on the head and laugh softly, and when my father came into the room – all five feet four inches of him, with the ridiculous little moustache that overhung his top lip – I would burst into uncontrolled sobbing.

Yes, my mother was a queen, and I have remained her most loyal subject. I must also make it clear, in order that her memory may remain pure and untainted, that there was never anything improper about the intensely intimate bond which bound us together; we understood each other perfectly, she and I – she by empathy and I by devotion – and I do not think that there could possibly have been two more precisely aligned souls than ours. Our love ran exceptionally deep, our relationship was remarkably complex and profound, yet I assure you (pace that sex-obsessed old Hebrew Freud) that it was ever chaste. You can well imagine therefore how unendurable it was for me to hear Heinrich Hervé impute grossness of sexual appetite to that noble, dignified, sensitive woman. Those afficionados of the Œdipus theory who wallow in their disgusting spermy daydreams of little boys murdering their fathers and having intercourse with their mothers could never begin to understand the beauty of the relationship which existed between my mother and me; their minds are too poisoned for that. It is certainly true that I frequently felt like murdering my father out of sheer pique, but neither an iota nor a jot of carnal intention ever shadowed the bright sunshine of love that shone in my heart for her. I find the very thought of such a thing utterly repellent.

The Incident in the Garden: A Mystical Marriage is Announced

At the back of our Highgate house we had a large garden which grew more-or-less wild, since my father only ever made desultory attempts to induce it to submit to some kind of suburban order, and heavy work with a spade or hoe was quite beyond the constitution of my mother, who was governed by that sensitivity and subtlety of temperament she had cultivated, de rigueur, as an actress; she who had once enchanted the Duke of Manchester with her exquisite portrayal of a woman torn apart by the conflict between love and duty, could hardly be expected to go wading about the convolvulus in wellington boots. On occasions I would wander among the cherry trees that grew close to the wall; beyond the wall was the garden of a funeral director called Jolly – an absurd name, which must surely have accounted for the final demise of his business, hinting incongruously as it does of flippancy and horseplay. No-one could be expected to entrust the final dispatch of their loved ones to a man called Jolly, and in the end no-one did.

On this particular afternoon – I still recall the shimmering heat, the vast expanse of blue sky, and the sound of quavering, grief-stricken voices raised in plangent lament coming from Jolly’s chapel-of-rest – I had gone into the garden to escape yet another paternal homily, when quite suddenly, there in the long grass, I saw the trembling, fluttering body of a small bird (perhaps it was a sparrow, but I can’t be certain), clearly in its death-throes. It had been badly mauled by a cat, as far as I could discern. Its globular black eyes (they were rather like the jet buttons on my mother’s best winter coat) were glazed and vacant; the torn wings flapped agitatedly but uselessly, and I could see the tiny thump-thump of its little heart still beating within its bloodied breast.

I was overcome with horror. I wished to put an end to its sufferings at once, but did not know how to do so; I could hardly just stamp on it, nor did there seem to be any implement to hand with which to carry out the task. There is no such thing as a special item of equipment designed for practising euthanasia on mortally wounded or terminally ill small animals and birds, and there never has been; bearing in mind the range of services we have developed for the benefit of the sick and suffering of our own species, I consider this a lamentable state of affairs. As it happened however, the poor creature itself relieved me of my distress by simply expiring. I picked up the mutilated body and cradled it tenderly in my hands. I brought it up to my lips to kiss it.

Then something very extrordinary happened: quite without warning, I was overwhelmed by the urge to suck its flesh. I could smell its still-warm body – a kind of tangy, sour-sweet, meaty odour rather like that of a wet dog. I was simultaneously comforted and excited by this. I didn’t want merely to smell it, I wanted to taste it too. Oh, how hard I had to fight against the desire to sink my teeth into its breast and insert my tongue into the rich, moist antrum, all darkly slick with blood! Strange images popped into my mind: small, blind creatures, new-born pups squashed tightly together in a deep, dank burrow beneath the surface of the ground … the pungent ripeness of animal haunches sweating after a swift run … the carious breath of a mother on the quivering snout of her whelp as fresh meat passes from the salivating jaws of one to the other … oh!

Shocked by this strange internal flux, yet certain that I had alighted upon some immensely significant and hitherto concealed item of self-knowledge, I threw the dead bird back in the long grass and ran into the house. In the privacy of my bedroom I stripped off all my clothes, lay on the bed, cradled my genitals between my cupped hands, and crooned softly to myself until I fell asleep.

That was the beginning of a recognition of what Dr Balletti calls my ‘mania.’ I myself do not accept it as anything of the kind, however; on the contrary, I believe it to be a true love affair – as true and as durable and as divinely preordained as Chopin’s infatuation with the pianoforte. That hot afternoon in our Highgate garden I encountered for the first time the workings of the Higher Will which was to govern the course of my life; moreover, without being able to identify or name the process, I knew deep in my heart that I had submitted to this Will without reservation. I had been introduced to the amniotic fluid in which I was hitherto to live and breathe.

I kept the secret of that recognition to myself; after all, I was not certain how sympathetically any self-revelation on my part would be received. Neither was I quite sure (indeed, how could I be, at that young age?) about the moral texture of it – I mean, was it laudable, or was it not? Did other people possess it? Now of course I know that they did – albeit that the elemental partner in their mystical marriage was other than mine: Michelangelo and his marble, Shakespeare and the English language, Herr Doktor Jung and the deep-sea waters of the human psyche. What are these if not perfect examples of his Mysterium Coniunctionis, the consummated nuptials of genius and medium? And to this list must surely be added the name of Orlando Crispe and his moist, yielding, blood-fragrant, tractable flesh.

My First Great Dish of the World

It was on my thirteenth birthday that I finally realized what my endless potterings in the kitchen and concocting of various little dishes had been leading to; I suddenly saw them – distinctly, aglow with the patina of retrojective significance and meaning – for what they were: a preparation, a training, an extended novitiate in the culinary arts. I knew then beyond any uncertainty that I was at last ready to be fully initiated into the beguiling secrets of the kitchen and to make my final vows to that Higher Will which had assembled the disparate fragments of my destiny into a coherent whole, before even my ridiculous father – panting and gasping and crooning glutinous inanities, no doubt – had first plunged his florid tool into the milky-white body of the woman it was my honour to call mother. In short, I was ready to dedicate my life to the vocation which divine grace had bestowed upon me. I would become a chef.

The manner of thus discerning my future path in life was in itself quite simple. My mother (with all her customary perspicacity) had brought me a little book called Great Dishes of the World Made Easy; my father’s birthday gift to me was an advanced chemistry set – his perspective was clearly that of the analyst whose essential task is that of decomposition, whose curiosity impells him to break things down into their disparate parts without having the slightest idea how to put them together again. My mother however, could not fail to understand that I had entered this world with the soul of an artist, born to create, to recompose, inspired by an intuitive visionary grasp of the whole – a vision as essentially divine as the analyst’s is demonic. As it happened, the first recipe upon which my eyes alighted as I riffled excitedly through the pages was for Boeuf Stroganoff; in that moment of magic and grace, I knew, beyond any doubt or uncertainty, oh! I knew that I had fallen irredeemably and irretrievably in love.

Boeuf Stroganoff

2 ounces (50g) of butter

2 large onions, coarsely chopped

4 ounces (100g) mushrooms, sliced

1/2 ounce (15g) plain flour

11/2lb (750g) fillet steak, cut into thick strips

1 tsp (5ml) mixed herbs

1 tbsp (15ml) tomato purée

2 tsp (10ml) French mustard

1/4 pint (150ml) soured cream

1/2 pint (300ml) beef stock

salt and black pepper to season

chopped parsley to serve

Melt half the quantity of butter in a pan on a low heat and brown the onions. Turn up the heat, add the mushrooms, and fry for several minutes. Then remove from the pan and keep warm in a dish. Season the flour with salt and black pepper and toss the strips of steak in the flour so that they are well covered. Melt the remaining butter in the pan and quickly fry the steak until browned. Add to the dish with the mushrooms and onions. Stir in the beef stock, herbs, tomato purée and mustard, return to the pan and bring to the boil, stirring thoroughly. Pour in the soured cream. Heat without boiling, stirring all the time. Serve sprinkled with parsley.

This was of course only a beginning, but it was a great success; my dear mother was generous enough to compliment me on the meal I served to the three of us – it was my father’s evening for his motor maintenance class, but out of sheer curiosity he had stayed at home, no doubt anticipating that my first attempt at one of the great dishes of the world would be a humiliating failure.

‘Well,’ he said, chewing on a sliver of beef, like a ruminating cow, ‘it’s all very well messing about in the kitchen for a hobby, if that’s what you like doing Orlando, but soon enough you’ll have to start thinking about the future.’

‘This is my future,’ I replied manfully.

My father shook his head slowly, a patient little smile appearing beneath his absurd, juice-smeared moustache.

‘You can’t make a living out of stew,’ he said.

‘It was Boeuf Stroganoff.’

‘It tasted like stew to me.’

‘I am going to be a great chef,’ I said.

To be perfectly fair, I have to say that he did not actually laugh in my face, but the expression of contempt and pity commingled that came over him was far worse than laughter. I never hated him more than at that moment. My mother, immutably self-possessed as always, sat in front of her empty plate without saying another word; however, as I got up to leave the table, she looked at me with perfect understanding shining in her lovely eyes.

I myself was utterly enraptured: the thought of how I had transmuted the flesh of a living beast – by some wondrous alchemical process, like lead into gold! – transported me into a higher, brighter dimension of reality; sweetened, spiced, enriched, the bouquet of its precious ichor lingered in my mouth like the aftertaste of a classic wine, the luxurious grace of a sacrament bestowed orally. More than this: it was flesh absorbed by my flesh, the two becoming one, a passionate act of giving, receiving and uniting far sweeter and more durable than the slippery jiggling of buttocks and groins in which I confess I have so often indulged. For me, it was a true exstasis.

The Light of My Life Untimely Expended

The dear, sweet, beloved queen of my heart passed from this earthly life shortly before the end of my schooling. Her constitution had never been robust; personally, I am inclined to believe that her early career on the stage had drained her of all vital energy. After all, the life of a successful actress is physically, emotionally and mentally demanding, requiring as it does total dedication of body and soul (all true art makes this demand upon the one who worships at its altar), and it is to be expected therefore, that suffering will inevitably accompany creative genius. I myself have been plagued by hæmorrhoids for years.

And yet, I was completely unprepared for her going. It was my father who first informed me that there was something seriously wrong with her.

‘You’d better sit down, Orlando old chap,’ he said, his face grave.

‘Why? What’s wrong? Is there something the matter?’

‘Yes. With your mother.’

I began to tingle all over with an electric current of apprehension.

‘Mother is ill? Where is she? If she’s ill, she will need me –’

‘No, Orlando, no. She’s upstairs, but Doctor Silvermann says she musn’t be disturbed.’

‘Why didn’t you tell me before?’ I cried, shaking an ineffectual little fist at my father. I couldn’t bear the thought that he had shared such a secret with my mother, excluding me from knowledge of her condition; indeed, I did not wish to contemplate the possibility that he knew anything about her that I didn’t.

‘We just didn’t realize,’ he replied, shrugging his shoulders helplessly. ‘You know what your mother’s like, never one to complain. She – well, she just left it too late, that’s all. The poor woman.’

‘My mother is not a woman,’ I screamed, ‘she is a lady!’

‘Don’t upset yourself, old chap. We’ll see what Doctor Silvermann has to say.’

It transpired that what Doctor Silvermann had to say was this: my mother was dying. I was never told what exactly she was dying of, but instead had to be satisfied with callously vague statements such as ‘completely exhausted,’ or ‘no resistance left,’ and ‘just wants to sleep.’ But who has ever died of sleep in the name of God, except (so I once read) undernourished natives in remote, swampy parts of the African hinterland, where all kinds of noxious vapours and horrible crawling things thrive? One did not die of sleep in Highgate, of that I was sure. My efforts to discover the truth were thwarted relentlessly and cruelly by my father, and every question I put to him was met by unsubtle evasion.

‘Why won’t you tell me?’

‘There’s nothing to tell old chap, believe me.’

‘How can there be nothing to tell? What’s wrong with her?’

‘She’s dying, Orlando.’

‘I know that already. What I want to know is why she’s dying.’

‘The poor woman. She’s no resistance left.’

Hearing that phrase yet again, I turned and fled from the room, my cheeks hot with unstoppable tears.

A week later, my mother was dead.

The Great Lie

It was the explanation my father finally gave me, barely a month after the funeral, that finally pushed me into the first major (and, in retrospect, one would have to say the most important) decision of my life. Even now, I have to make an effort to prevent myself from trembling with rage when I recall the magnitude of his wickedness! How he could for one moment have expected me to believe him, I simply do not know. I have since considered the possibility that grief had unhinged him, but it is more likely that being jealous of the deep bond between mother and me, he was attempting (vainly, I need not say) to slander and befoul the pure memory of that sweetest of women, which he knew I cherished as a sacred trust. This was precisely what I thought at the time, and I still think it now. I was of course surprised (not to say shocked) at the manner in which this attempt was made, but not that he was capable of it. Poor mother was blind as far as my father was concerned, for wifely duty and loyalty to her husband had always been an inviolate principle of her life; the irony is that if she had been a person of less exacting ethical standards, she might not have been obliged to spend the greater part of her cruelly short life saddled with such a nonentity as my father. Our sojourn in this world is chock-a-block with ‘ifs,’ so they say.

I was in the bath when he made his vile announcement; I do not know why he chose this particular moment, but I imagine that he thought my nakedness would render me more vulnerable, less capable of expressing outrage and disgust than I otherwise might have been. He was quite wrong. At the time, I was even prepared to get out of the bath and face him squarely, even though this would mean exposing my puckered genitals; in fact I actually did so, as you shall shortly learn.

‘I suppose it’s time you were told,’ he murmured, in a tone of voice which made it very clear that some dreadful information was about to be imparted.

‘Told what?’ I asked, making sure that there was plenty of foam between my legs; I still retained a disturbing (but far from unreservedly unpleasant) memory of the time he had lasciviously explored my scrotum.

‘About your mother.’

‘She died of sleep, didn’t she? That’s what you and Doctor Silvermann said.’

I did not attempt to hold back my bitterness.

‘I know how you must feel,’ replied my father, and to my horror he placed one hand on my back. Then it moved down a fraction.

‘You can’t possibly know,’ I said with great dignity.

‘Yes I can, and I do. Of course I do. Don’t you think I still grieve for her, Orlando? I’ve lost her too, haven’t I?’

Ominously, the hand slithered, a capriolated alien thing, round to my chest. I shuddered.

‘I’m trying to take a bath.’

‘And I’m trying to tell you about your mother, Orlando.’

‘It’s too late for that,’ I said.

He looked down at me and smiled. It was nauseating.

‘It’s never too late,’ he answered, like someone encouraging an octogenarian to take up driving lessons or evening classes in pottery.

‘Then what is it you have to say?’

‘Something that should have been said a long time ago, if she had allowed it.’

‘Allowed it? What do you mean?’

My father uttered a small, apologetic cough.

‘You and I – well – we never really had any man-to-man chats, did we? Never sat down together and really talked about things?’

‘No.’

‘Like father and sons ought to do, Orlando.’

‘Ought they?’

‘You were never interested in that, I dare say.’

‘You’re right – I wasn’t.’

He sighed, and the hand on my chest began to move in a slow, circular motion.

‘Don’t make it harder on me than it already is, Orlando, please. It’s just that – well – just that you wanted to know, and now I think you’re prepared for it. As God is my witness, I never wanted to keep it from you! But what could I do? We discussed it often, your mother and I, although she was always adamant that you were never to be told anything while she was alive. “He’s just a child,” she said. “How can you expect a child to understand?” So I let her have her way, and we said nothing. Besides, we often wondered whether or not you had a right to know. Even a mother is entitled to her own secrets, Orlando –’

‘There were no secrets between her and me!’ I cried, and the soap slipped out of my hands, plopping into the water through the foam I had piled up between my legs; I peered down into the hole and saw my wrinkled penis bobbing languorously below the surface.