9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

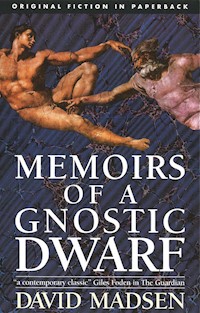

- Herausgeber: Dedalus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Included in The Guardian's one thousand novels to read before you die.It is a baroque masterpiece.

Das E-Book wird angeboten von und wurde mit folgenden Begriffen kategorisiert:

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Title

Epigraph

Foreword

Incipit Prima Pars

1518

1478 onwards

1496 onwards

1503 onwards

1509 onwards

Incipit Secunda Pars

1511 onwards

1513 onwards

1518 onwards

1520-1521

Epilogue

About the Author

Copyright

A Michele, Cuor’ Addorato Mio

Spirto ben nato, in cui si specchia e vede

Nelle tue membra oneste e care

Quante natura e’l ciel tra no’ può fare,

Quand’ a null’ altra suo bell’opra cede:

Spirto leggiadro, in cui si spera e crede

Dentro, come di fuor nel viso appare,

Amor, pietà, mercè cose sì rare. . . . .

Che ma’furn’ in beltà con tanta fede:

L’Amor mi prende, e la beltà mi lega;

la pietà, la mercè con dolci sguardi

Ferma speranz’ al cor par che ne doni.

Qual uso o qual governo al mondo niega

Qual crudeltà per tempo, o qual più tardi,

Cà sì bel viso morte non perdoni?

(Michelangelo: Sonetto XXIV)

FOREWORD

It is not necessary for me to relate precisely how these memoirs fell into my hands; suffice it to say that in addition to a sound academic reputation, I also have a private income.

What it most certainly is necessary to say however, is that the task of translation presented its own peculiar difficulties. I have tried to overcome these difficulties by maintaining throughout the text a fairly contemporary – and therefore accessible – idiom; many of the expressions which Peppe uses in his fifteenth and sixteenth century Italian for example are virtually untranslatable, and I have taken the liberty of replacing them with modern equivalents. This is particularly so in the case of vulgar expletives. When he uses puns or double entendres, I have applied the same rule of thumb: where it is translatable I have kept to the original, and where it is not I have substituted. It is in this way that I have attempted to preserve the esprit of the memoirs, which is, by and large, somewhat salacious.

There are several portions of the text (mainly songs, poems or quotations) which I have left untranslated – Peppe’s own song for example, Ulrich von Hutten’s bilious little political ditty, and snippets of private letters – because I considered it would be a great pity to lose the unique flavour of the original; even to one who does not speak Italian, the radiant beauty of Nel Mio Cuore will be obvious. In any case, as our little friend himself points out – all translations are to some degree or other interpretations.

The fragments of Gnostic liturgies were written down by Peppe in the Original Greek, but it seemed to me that they should be given in English in this edition of the memoirs, and this has been done; the reader need not be unduly concerned however, since they are for the most part incomprehensible in either (or any) language. There can be little doubt that Peppe’s adherence to Gnostic teaching was total and unreserved, yet even he admits in his apologia pro philosophia sua that much of its written expression (especially the invention of fantastic titles and grotesque honorifics) is but a prolix attempt to identify the Unidentifiable. To anyone who might be interested in learning more about the historical development of Gnostic rites and liturgies, I would wholeheartedly recommend Professor Tomasz Vinkary’s epoch-making tome, A Study of the Valentinian Sacramentary in the Light of Gnostic Creation Myths, which has recently been reissued by Verlag Otto Schneider of Berlin in co-operation with Schneider-Hakim Publications, London.

There are many individuals to whom I owe a debt of gratitude for their invaluable help in the preparation of these memoirs, but I feel I must make particular mention of the following:

Herr Heinrich Arvé, who supplied me with much invaluable information on the incidence of sexual perversion in Renaissance Italy; Monsignore Marcello Ciapplino, for his elucidation of those parts of the original text which deal with military and political history; and Dottoressa Patrizia Cezanno, who painted a portrait of Peppe using the description he himself gives in the memoirs, which now hangs in my private library.

The reader may care to know that Giuseppe Amadonelli died on 6th August 1523, the Feast of the Transfiguration, whilst attending Solemn Vespers in the church of Santa Maria in Trastevere, Rome. The precise cause of death remains unknown.

David Madsen

London, Copenhagen, Rome

INCIPIT PRIMA PARS

– 1518 –

Clementissime Domine, cuius inenarrabilis est virtus

This morning His Holiness summoned me to read to him from St Augustine, while the physician applied unguents and salves to his suppurating arse; one in particular, which was apparently concocted from virgin’s piss (where did they find a virgin in Rome?) and a rare herb from the private hortus siccus of Bonet de Lattes, the pope’s Jewish physician-in-chief, stank abominably. Still, it was no worse than the nauseating stench of the festering pustules and weeping ulcers adorning His Holiness’s cilicious posterior. (Everybody refers to these repulsive afflictions as a ‘fistula,’ but I am not constrained by the self-interest of tact.) With his alb pulled up over his hips, and his underdrawers down around his ankles, the most powerful man in the world lay sprawled on his bed like a catamite waiting to be well and truly buggered.

He has been buggered, plenty of times – hence the state of his arse. His Holiness prefers to play the womanly role, thrashing and squealing beneath some musclebound youth like a bride being penetrated for the first time. Not that I’ve any personal objection to such behaviour – Leo is the pope after all, and short of publicly declaring that God is a Mohammedan, he can do exactly as he pleases. Besides, I like to think of myself as a tolerant man. I find it easy to overlook weakness and vice in a field of human activity which holds no interest for me whatsoever. Even if it did, I imagine it would take someone with a very peculiar vice indeed to find anything sexually attractive about a crook-back dwarf. Which is what I am.

Hence the title of these reminiscences of mine: Memoirs of a Gnostic Dwarf. I think this is an excellent title, since it is utterly honest: I am a Gnostic dwarf, and these are my memoirs. It occurs to me that there are a great number of books and manuscripts offered for sale these days whose claims are entirely meretricious, such as Being a True Account of a Monk’s Secret Pleasure, or A Full and Satisfactory Explanation of the Practice of Greek Love – both of which I have seen in His Holiness’s personal library, and neither of which are in any way true, full or satisfactory; you shall not be likewise misled in these pages. It is painfully evident to everyone that I am a dwarf, but my Gnostic proclivities remain my little secret … and that of a certain private fraternity. Yes, there are more of us – Gnostics I mean, not dwarves. Later, I shall speak of the fraternity in detail.

His Holiness Leo X, Roman Pontiff, Vicar of Christ on Earth, Patriarch of the West, Successor to the Prince of the Apostles, Holder of the Keys of Peter and Servant of the Servants of God, does not usually call me to read to him while he is having his rump anointed with virgin’s piss and rare herbs; on the contrary, he likes to be alone with his physician, and one can well understand why. I was therefore a little surprised to receive the summons. However, reflection on the matter suggests that he is disquieted by the latest news from Germany, where a choleric friar called Luther has been stirring up trouble, ranting and raving about the corruption of the papal court, and it may be that he finds the misanthropic rhapsodies of the holy bishop of Carthage distract him. To speak personally, I find them tedious in the extreme. The papal court is corrupt, but what of that? Everyone expects it to be. It’s been corrupt for so long, no-one can remember a time when it wasn’t, nor conceive of it ever not being so. To speculate on the whys and wherefores, as this Luther seems to be doing, is like asking why the sun is hot or why water is wet, and trying to make them otherwise. Futile. Vanitas vanitatum. The trouble with people like our fractious friar is that they think they’re a cut above everyone else, and thus ideally qualified to put the world to rights; but the world never can and never will be put to rights, because it is hell. (Now there’s a snippet of Gnostic wisdom for you.) That doesn’t make me a misanthrope like our holy father St Augustine – on the contrary, if this world is hell, one can only have compassion for those who are obliged to live in it and breathe its poisonous air. And – above all! – to teach them that there is a way out.

“I think this may call for a papal bull, Peppe,” His Holiness said to me (for Peppe is my name).

“Lie still, Holiness,” admonished the physician, inserting a gnarled forefinger into the petrine rectum with mathematical care. He moved it around a bit, withdrew it, brought it up to his nose and sniffed cautiously.

“Not yet,” I answered, disgusted by the antics of this overpaid, underworked scryer of excreta, “let our scripture-happy friend stew a while in his own juice. Besides, he may mean no harm.”

“No harm?” Leo squeaked. “No harm? Have you heard what he’s calling me?”

“Well, one tries not to listen to the latest court chronique scandaleuse, Holiness …”

“This isn’t gossip, Peppe, it’s common knowledge. He makes no bones about it. He calls me a usurer, a nepotist, Sodom’s favourite catamite –”

“Well …”

“God’s blood and the Virgin’s milk, he’ll be attacking the Mass next!”

“Perhaps you ought to make him a cardinal, Holiness.”

“Are you trying to be funny?”

“Of course. That’s partly what you pay me for.”

Leo screamed just then – a long, wailing scream of genuine agony.

“Haven’t you finished yet, you witless whore’s cunny!” he roared to the unperturbed Bonet de Lattes; Leo’s colourful language was well known and hence no-one took any offence at it except the pious – of whom, fortunately, there are but few at court.

“Very nearly, Holiness.”

He seemed to be examining a minute piece of shit that was adhering to a fingertip. Examining it for what, I could not imagine.

“You think I ought to wait a little, do you, Peppe?”

“Precisely, Holiness. Let him walk on thorns a little longer, then let him have it. A real broadside.”

“Exsurge Domine. How does that sound?”

“An excellent title, Holiness. But save it for later.”

“Your Holiness may re-attire,” the physician said pompously (in my experience, physicians are invariably pompous), rinsing his hands in the bowl of rosewater that stood on Leo’s reading table.

“Well, what’s the verdict?”

“The affliction is improved, naturally –” (Note: read thanks to my skilful and therefore necessarily costly ministrations) “– but the medication will have to continue. And perhaps an increase in bleedings. I will call again next calendar month.”

“I will summon you to call,” Leo said snappishly. “Your fee is there. Now get out.”

“Thank you, Holiness. And – if I may suggest – you might for some period of time refrain from –”

Refrain from accommodating half the young stallions of Rome, I thought.

“– from all highly seasoned food. It would help. The blood must not become overheated.”

“Alright, alright. Now go.”

De Lattes walked backwards towards the door, bowing and fawning, clutching his little bag of money and his Asklepian caduceus tightly to his fur-draped chest.

Leo hauled himself into a sitting position and glanced around the room with rheumy, vengeful eyes, as if searching for something or someone to strike.

“If my blood is not to become overheated,” he said, “I must hear no more of this German friar.”

“Does Your Holiness wish me to continue reading from the saintly bishop of Carthage?”

“Luther’s an Augustinian, isn’t he?”

“So I believe, Holiness.”

“Then let Augustine go sodomize himself. I feel peckish after all that probing.”

Leo is a fairly tall, fattish (some, unkindly, might say bloated), swarthy man; he walks with a rapid waddle and rides side-saddle on account of his ulcerated arse; his face is full-fleshed, his eyes – always watchful and smouldering with suspicion – are heavily lidded, the caruncles thickly veined, and his lips sensuously ripe. Incongruously his speaking voice, although elegantly modulated, is somewhat high-pitched except when he is roused to anger (which is quite often, since he is of an irascible temperament), when it becomes a truly terrifying roar. I have already told you that he has a tendency to use somewhat flamboyant language. He is shortsighted, and when his vanity allows him to he makes use of a small magnifying glass whilst reading. And as you now know, he is a devotee of Ganymede. He likes to be taken from behind by young men. I do not think he is interested in women in the slightest. Oddly enough, there is no public scandal attached to this predilection; either people take it for granted, or they just don’t care. In any case, compared to the athletic antics of Leo’s unillustrious predecessor but one (well, one and a bit really, since Pius III only reigned for twenty-six days), the pox-riddled and impious Alexander VI Borgia, Leo is a temperate man. Indeed, he is genuinely pious, and always hears Mass before going off to the hunt. He loves hunting.

His Holiness is not at all an unamiable man; in fact, when the occasion calls for it, he is capable of exercising a pungent sense of humour. Once, when I was helping him to unvest after a solemn High Mass, he turned and looked at me with curious eyes, and out of the earshot of the deacons and acolytes who were mincing and prancing all over the place, he said to me:

“Tell me, Peppe … is it true what they say about dwarves?”

“Is what true, Holiness?” I said, pretending not to understand.

He put a pudgy, jewel-laden hand on my arm and drew me a little closer to the pontifical person.

“You know exactly what I’m talking about. Well, is it true or not?”

“See for yourself,” I said, and unfastening my hose and pulling down the linen-stuffed leather codpiece, I drew out my prick. All three inches of it.

Leo smiled and sighed.

“What a pity,” he said. Then he removed a ring from one of his fingers – a huge chrysoberyl bearing an Egyptian glyptic, encircled by tiny pearls and set in an intricate oval of gold filigree – and pressed it into the palm of my hand.

“Here,” he said. “With a cock as small as the rest of you, you deserve some consolation.”

A gesture, I may say, that moved me profoundly. It was only later, during an audience with the unctuous and gasconading Venetian ambassador, wondering why I had suddenly become the cynosure of surprised and outraged glances as I stood beside the papal throne, that I realised I’d left my cock hanging out. Leo must have noticed, but decided to say nothing. Much to my chagrin, the ambassador had enough self-righteousness to complain about this incident, but he got his come-uppance at the banquet held in his honour that same evening: one of the delightful specialities served up by His Holiness’s Neapolitan cook, consisted of larks’ tongues basted in wild honey and cassia, each wrapped in a folio of gold-leaf and served on a bed of baby pine-cones with crushed emeralds; not having enough common sense to realise that the cones and emeralds weren’t meant to be eaten, he shoved a great spoonful into his mouth and swallowed, before anyone could stop him. He spent the rest of the evening in one of the papal privies, retching up blood.

Leo almost laughed himself into a coma.

I have been His Holiness’s chamberlain for five years now, having come with him to Rome from Florence, upon his elevation to the Chair of Peter; before that, I had been retained in his household on rather ambiguous terms, as a sort of superior personal servant. I only came to be known as His Holiness’s chamberlain when I joined the papal court; the term ‘chamberlain’ is somewhat degrading, and certainly inadequate to describe properly the extent of my duties, since I am also his confidant, general factotum, spy, scribe, and constant companion. He has a confessor, naturally – a glacially pious young Benedictine, chosen by Leo because of his excessive handsomeness – but into my hairy little ear are poured all his fears, hopes, dreams and aspirations. I am there, in a sort of way, and insofar as a middle-aged dwarf can be described as ‘motherly,’ to mother and cosset and console His Holiness when the burdens of his high office afflict his soul with melancholy. I am also on occasions his pimp, although this rather distasteful duty has become less frequent since the trouble with his arse began.

“I think I may have a rather private and personal mission for you,” he would say.

“When, Holiness?”

“This evening.”

“Any particular preference?”

“Well-built, naturally.”

“Well-built, or well-endowed?”

“Both, of course.”

And off I’d go, loping about the stinking, tenebrous alleyways of the city. Once or twice the young men I approached formed the erroneous conclusion that I was soliciting on my own behalf. A particularly juicy-looking specimen with broad shoulders and sinewy (I nearly wrote ‘simian’) arms that suggested years of heavy daily labour, looked me up and down with contemptuous dark eyes and said:

“You’ve got to be joking, of course.”

“You’ll be well-paid.”

“I dare say, but I’m not that hard up. Holy Peter’s bones, the monster between my legs would tear your innards out, little runt that you are.”

“It isn’t for me, you idiot.”

“Oh? Who for, then?”

“As I said, you’ll be well-paid. Just follow me.”

“How well paid, exactly?”

“What about a plenary indulgence?” I said. “You look as though you could do with one.”

“Piss off, short-arse.”

“Is that the reply I am to give to the Successor to the Prince of the Apostles and Holder of the Keys of Peter? He’ll have that monster of yours sliced off at the root and stuffed down your impertinent throat. Well, are you coming or not?”

He came.

I am sure – indeed, I know – that Leo is genuinely fond of me; thanks to his generosity, I have managed to accumulate, to console me in my old age, a substantial nest-egg which is lodged with bankers in Florence. I also have quite a collection of rings, all of them consisting of precious stones set in gold or silver, but these are hidden in a private place in my chamber, which I will not describe here. I never wear them. It’s not that I don’t want to, but it has been my experience that for some reason people dislike seeing beautiful things adorning an ugly, misshapen body such as mine. I find this attitude incomprehensible, since no-one objects when a plain-looking woman directs attention away from her plainness by means of expensive clothes and exquisite jewellery – indeed, they seem to expect it; but glittering, glamorous dwarves are offensive, apparently.

I may say that it is precisely these multifarious duties of mine, and this comfortable intimacy I have with His Holiness, which prevent my life at the papal court from becoming nauseatingly tedious; I assure you – all you who dream of such things in your secret dreams – that endless banquets, interminable High Masses (especially the High Masses), innumerable audiences, receptions, and day after day every conceivable kind of glittering pomp, soon become unutterably wearisome. High Masses apart, I know you will object: “How easy that is for you to say, you who have enjoyed all such extravagances!” Well, let me tell you now that I would be happy to exchange my lot for yours, however lowly your calling may be, however revolting the hovel you are obliged to dwell in; but then, if we were to trade the beings we are, one for another, you and I, you’d have to reconcile yourself to living in the twisted, cumbersome body of a dwarf. Would you want that? And I – I would know, by an ontological miracle, the cleanness and purity of straight limbs, the dignity of a head that’s a reasonable distance from the feet, the sheer relief of being able to stand upright – oh yes, how I used to weep with longing for that. Not anymore. Later, you will learn how and why the weeping and the longing ceased, and in what manner I learned to accept myself as I am.

Speaking of High Masses, I might say that these were always somewhat problematic for poor Leo, since some of them dragged on endlessly (and still do, alas), and His Holiness would invariably be overcome by the need to relieve his aching bladder. It was painful to watch him wriggling and squirming on the papal throne, swathed in his heavy pontifical vestments, his face a mask of agony as the choir screeched on and on with some twaddlesome litany. I don’t think he ever actually pissed in his underdrawers, but he must have come pretty close to it. Happily, I was able to come up with a little device of my own invention, which solved the problem: I stitched together two pieces of soft leather lined with otter’s fur to make a kind of casing or sheath, which fitted snugly over His Holiness’s fat penis; from the tip of the sheath I ran a tube, also of leather, which was attached to a lined bag that I bound with silk to his right calf. The entire apparatus was worn beneath the underdrawers, and enabled Leo to pee freely, standing or sitting, in the middle of solemn High Mass (or indeed, in the middle of any protracted ceremony) without anyone knowing what he was up to. Only the blissful expression of sweet relief on his face would have given the game away, and then only to the acutely observant. His Holiness was absolutely delighted, and suggested that in the interests of east-west rapprochement, I might care to send one to the Patriarch of Constantinople, who was apparently obliged to endure even longer liturgies than our own; I did this, but received no reply. I didn’t get the apparatus back either. Sometimes I like to think of the curmudgeonly old renegade happily peeing his way through the most prolix and tedious of ceremonial marathons, thanks to my ingenuity; they say that the eastern schismatics are full of piss and wind, anyway. Actually, I later discovered that it wasn’t my own invention at all, and that such devices were quite common; I read that even the physicians of the ancient kingdoms of Egypt used them to ease the sufferings of those who were unable to urinate. Needless to say, I didn’t tell Leo this, and as a reward he gave me another ring – a truly stunning emerald set in scalloped gold, said to have once belonged to the holy Apostle John himself. However, I don’t believe that for a moment. Not unless it popped out of the ganoid belly of a gutted fish.

Leo’s cousin Giulio – a cardinal, needless to say – is continually creeping about the place, sucking up to Leo in the hopes of further benefices and endowments; secretly, he despises him. Ah, but if this contumely is secret, I hear you ask, how do I know of it? Well, it isn’t exactly the deepest and darkest of secrets (except to His Holiness himself) and furthermore, I overheard Giulio one night in a corridor in the papal apartments, discussing with Lorenzo, His Holiness’s nephew, how much it was going to cost to assure himself of the papacy when Leo went to meet his Lord with a lot of explaining to do, and how it was to be managed. I listened to them unseen – one of the advantages of being a dwarf is that you’re less obvious, especially in the dark; in the dark people tend to look straight ahead, not down. Their conversation left no doubt that Giulio and Lorenzo regarded Leo merely as a temporary source of income. They were quite explicit in articulating their disgust at his sexual inclinations and habits, and I shall not repeat their comments here, out of respect for His Holiness. Besides which, Giulio’s hypocrisy is quite breathtaking when one considers that His Eminence has been humping his way through the ladies of Rome’s patrician families for years and finding time to fit in (literally, as well as chronologically, if you catch my drift) the occasional good-looking young lad. The following morning there he was, sneaking into the papal bedroom again, even before Leo was up and about, oozing charm and dripping flattery. I despise him. His Holiness deserves better. However, I shall write at greater length of this manipulative creature a little later.

Please do not think that Leo is a gullible man simply because his cousin deceives him with false devotion – he is far from it; however, it is an obvious truth that the heart is more willing to be duped than the head. His Holiness is in all other respects an individual of profound acumen. I recall, for example, the affair of the miraculous icon. This was a religious painting, executed in tempera on wood and inlaid with gold, such as is very popular among the schismatics of the east, and it was brought to Leo by a Venetian merchant of apparently impeccable credentials who informed the papal court that he had acquired it for a fabulous sum from an Ottoman dealer, who had himself purchased it from a close relative of a certain Caliph, who … and so on. He told us that its history was long and thrilling, hallmarked by mysterious disappearances and reappearances, miraculous healings, clandestine bargaining, and even robbery and murder. He said that the icon, which was of the Theotokos orans, the Mother of God at prayer, was reputed to have been painted by blessed Luke the Evangelist himself. After all this preliminary salesman’s waffle, it did not take him long to get to the point: his asking price was three hundred ducats. Some of the assembled court gasped at this, even though (while nobody believed the rubbish about St Luke for a moment) it could not be denied that the icon was truly exquisite.

Leo sat back on his gilt chair, his feet almost touching the crimson velvet footstall, one plump hand under his several chins. He smiled a slow, secretive, contented smile.

“No,” he said.

The court gasped again, and the pale, supercilious-looking merchant frowned.

“Your Holiness is refusing such an ancient artifact? A representation of the Holy Mother of God, with such a lustrous pedigree that it is not beyond probability that the blessed Luke himself executed the work?”

“No,” Leo said again. “I am not refusing such a marvel. I am refusing what you offer me.”

“But Holiness – surely for the greater glory of the Holy Roman Church –”

“Take him away. Let him cool his enthusiasm for his wares in a cell. I don’t mean the monastic kind, either. Away!”

The merchant was led off, still protesting. I never saw him again; I doubt very much if anyone else did either, and the icon still reposes on Leo’s bedside table.

Later, when we were alone, I asked him:

“But why? It was a wonderful thing, surely?”

“Indeed it was,” the pope answered, “but worth no more than thirty ducats. It was probably done less than fifty years ago. Even if it is older, it’s certainly not the antique that avaricious little bastard made it out to be.”

“But Holiness, how do you know?”

Leo sighed, and placed a fat hand on my knotty shoulder; I hate anyone touching me anywhere near my hump, except him.

“Have you ever seen the Holy Shroud of the Lord?” he asked.

“The linen sheet in which the body of Jesus was wrapped, and which is impressed with his image?”

“Yes.”

“I’ve never seen it.”

“There is a bloodstain – a trickle – that seeps down from his hair, in the centre of his forehead. Blood, we suppose, from the thorns that pressed so deeply into his poor head. That miraculous image of the trickle of blood was mistaken by the icon painters of the east for a lock of hair, and you will see it in all the later representations of the Lord. The later representations in the eastern style. Did you see such a lock in the icon we were shown, and which we were asked to believe was so ancient?”

“Yes I did, Holiness.”

“Therefore?”

“Therefore it is not ancient –”

“At least not as ancient as our thieving friend would have had us believe. It is indeed a beautiful work, but many of the same kind are to be found all over the east.”

“Your Holiness astounds me!”

“My dear Peppe, I am perhaps not so much of an ox as I look.”

As a matter of fact, we were frequently plagued by all sorts of shifty, seedy-looking characters hawking relics of every kind: a phial of the Virgin’s milk, wood-shavings from the workshop of St Joseph, one of St Agatha’s breasts (in colour and texture this resembled a prune –“She must have been rather a small person,” His Holiness remarked, amused), an arrow that had pierced the flesh of St Sebastian, and most grotesque of all in my opinion, a pubic hair from the groin of the saintly English Cistercian, Aelred of Rievaulx – presumably plucked out by one of the many special friends he made during his life in the cloister. This latter intrigued Leo no end, for he was very fond of Aelred altogether, and had read De Spirituali Amicitia with intense pleasure, so he gave quite a sum for it. I do not know what became of it, but being so small and lightweight, it was presumably difficult to keep track of. Even Leo did not go so far as to have a pubic hair mounted on satin, encased in a gold reliquary, and hung on the wall of his chapel, where all the other pious flotsam and jetsam reposed.

“For purely private devotion I think,” he remarked coyly to me.

Some came with no wares to sell other than their alleged personal talents: “I shall transmute lead into gold, Holiness …” or: “I am accompanied at all times and in all places by an angel, Holiness, and for a small financial consideration, shall attempt to materialize him for you …” and even: “The futures of men are as an open book to me, my lord pope!”

To this last, Leo said:

“Can you read your own future, then?”

“Indeed I can.”

“And what do you read, pray?”

“Travel, Holiness; journeys across the sea, consultations with powerful men –”

“You’re wrong, I’m afraid.”

“Holiness?”

“Your future is in a damp, dark place somewhere in one of my prisons.”

I’ve told you already that Leo demonstrates a fine sense of humour when the occasion demands.

He wasn’t in the mood for humour, however, when a summary of Martin Luther’s attack on indulgences arrived for His Holiness’s perusal several days after the humiliating examination of his arse.

“What? How, by the scourging of sweet Jesus, does this idiot imagine I am to finance the reconstruction of St Peter’s? The work is already going too slowly for my liking. The preaching of indulgences is an absolute necessity.”

“The war with France hit the papal coffers hard, Holiness.”

“Don’t remind me of that poxy Mechelen League; thanks to that arrogant little tit-sucker Francis, I barely have enough funds to pay my cook. Peppe, this is too much. I think – what did I say I’d call it? –”

“Exsurge Domine, Holiness.”

“Exactly. It’s time for a papal pronouncement.”

“I would counsel patience, Your Holiness,” I said.

“Christ’s blood, I’ve been patient for too long already!”

“They say that Frederick of Saxony protects this German heretic …”

“I know, I know.”

“And Maximillian cannot last forever …”

“I know that too.”

Leo heaved a pitifully deep sigh.

“Besides which,” I said, suddenly and fortuitously inspired, “Master Rafael arrives this afternoon to work on your portrait. You need to be in a relaxed frame of mind for that. Forget the mad monk for a while.”

At the mention of Rafael’s name, the anger melted from Leo’s eyes, and they became dreamy, full of poignant yearning.

“Yes, Master Rafael,” he murmured.

As I am sure you must immediately have guessed, Rafael is a handsome fellow, thirty-five years old but looking twenty-five, slim and willowy of figure, all poise and grace and sweet sadness, bulging sumptuously between the legs – with either nature or artifice; rumour has it that it’s so long, he has to roll it up inside his codpiece. I don’t believe this; after all, would the God who was cruel enough to give me this twisted, stunted body, have the generosity to bless a man with the face of an angel and a ten inch cock? They say that women finger their private parts and swoon when Master Rafael passes; Leo almost does the same at the mere mention of his name.

“Rafael,” he repeated. And the mad monk was quite forgot.

Four years ago, against what I consider to be sound advice, Leo appointed Master Rafael as chief architect of the new St Peter’s, in succession to Bramante; I am sure that this was only because Leo had been so impressed by the stanze Rafael decorated (exquisitely, I admit) for Pope Julius. Yet why should we assume that a talented painter must also be a talented architect, any more than we would expect a skilled physician to be a skilled singer too? These days I doubt that anyone expects a physician to be skilled at all; in case you haven’t already guessed, I’ve got a raw nerve about physicians.

Rafael not only looks like an angel, he paints like one too. His elegant, effortless strokes are a joy to watch. He had Leo sitting dressed in simple morning attire at his reading table, a pious book of some kind open in front of him, his little crimson fur-edged camauro pushed down onto his rather ungainly head. On the damask-covered surface of the table there was also a beautifully chased bell, and in his pudgy left hand Leo held his magnifying glass. I think he was supposed to be examining the illuminations in the book. Giulio had somehow managed to worm his way into the picture, and his supercilious, badly-shaven face was beginning to emerge on the canvas; he was depicted with one hand resting ominously on Leo’s chair, the upper half of his body bent in a fawning, unctuous gesture. For some reason I could not quite fathom, Cardinal Luigi de Rossi, who had happened to walk into the room during a previous sitting, was now a permanent fixture in the portrait. I did ask if I could be in it too – an idea Leo approved of – but Master Rafael, casting his lovely doe’s eyes up and down my ugly little body, said quietly:

“Alas, it would be beyond my skill. I am able to paint only what is beautiful.”

There was clearly no malice whatsoever in this remark – it was merely a statement of fact – and so I did not take offence.

“Can’t you make me beautiful?” I asked. It was only a tiny glimmer of hope.

Rafael shook his head, and his gorgeous pennanular tresses moved like ripples of water in a caressing zephyr.

“I cannot undo nature,” he said sadly. “I can only imitate it.”

And with that, I had to be content.

“Are you beautiful then, Holiness?” I asked Leo later.

“No,” he said, “but my money is.” Then he farted, uttering a little squeal of pain as he did so.

In fact, His Holiness was a prodigious farter; he was famous for his farts. They came, with surprising frequency, in various degrees of duration and odour; sometimes it happened on the most inappropriate of occasions, such as an elevation to the cardinalate, or at dinner with an ambassador, and even during Solemn High Mass. That was one thing I couldn’t invent a device for. He once let rip with an absolute stinker whilst granting an audience to some curial prelate; writhing with embarrassment, and anxious to preserve His Holiness’s dignity at all costs, the silly little sycophant muttered:

“I beg Your Holiness’s pardon.”

“Why?” Leo said, all wide-eyed with innocence. “What have you done?”

The prelate knew that Leo knew that he knew who had been responsible for the fart, and found himself on the horns of an impossible dilemma. You could almost hear the fucus stirring in the stagnant pond of his mind. Red-faced with shame and confusion, he said:

“I think – quite possibly, I mean – that I may have involuntarily passed wind.”

From that moment until the day he died (which was soon afterwards, and of humiliation, I always insisted), the wretched idiot was known to the entire papal court as ‘the man who possibly farted’.

A papal toady once suggested that the expelled air should be bottled, or sealed in jars, and sold as objects of devotion. Leo was furious.

“Do you suggest that I go around with a jar strapped to my arse? Or am I to inform the entire household whenever I feel a fart coming on, that they may come running from the kitchens armed with phials and bottles?”

Short of money though he always was, even Leo wouldn’t stoop to hawking his own bottled farts.

Quite simply, Leo was continually out of funds because he was continually spending: rare manuscripts, exquisitely illuminated books, fabulous jewels, ancient artifacts from far-flung parts – whatever spoke to him of human skill and ingenuity, of the workings of the human mind and the march of human history, he bought. This is hardly surprising when one remembers that Marsilio Ficino and the enigmatic, esoterically-inclined Pico della Mirandola were his boyhood tutors. Leo’s father, Lorenzo the Magnificent, certainly knew what a sound education was all about. Mind you, they do say that it was none other than Giovanni Pico della Mirandola who first introduced Leo to the tender art of buggery at the equally tender age of eight, which was when – predestined for high ecclesiastical office by his shrewd, arrogant, overbearing, self-indulgent and, yes, truly magnificent father Lorenzo – he received the tonsure. Pico della Mirandola had his head stuffed with all this occult hermetic nonsense and tried to stuff Leo’s head with it as well, but did not succeed; he also tried to stuff his arse, and was only too successful, I gather. An inordinate fondness for books and buggery were Pico’s most enduring bequest to His Holiness; it’s the books that really damage the papal coffers.

Leonine Rome has been a lucrative haven for every peddler of verses, penner of plays both decent and indecent, artist, philosopher and littérateur; scholars and classicists, librarians, colporteurs and antiquaries thronged the court. Indeed, at the time of his election, it had been widely assumed that Leo would introduce a golden age for scholars, poets and artists, and the city was adorned with inscriptions which declared the arrival of the epoch of Pallas Athene. If Julius II had paid homage to the art of war, everyone looked to Leo to pay homage to the Muses; and indeed he did, rather profligately. Such devotion was not cheap.

Master Rafael dined with us in the evening. Much to my annoyance, the pope put him in my chair, close by himself, and I was consigned to the end of the table. I saw Leo glance at me with doleful eyes, as if to say: I know, I know, but I’m utterly smitten with him, so forgive me for once! Well for once I wasn’t in the mood to forgive, so halfway through the breast of chicken served with spiced colchicum sauce, I shamelessly introduced the subject of the mad monk, knowing only too well what an effect this would have on Leo.

“Did you say something?” he hissed at me, his eyes no longer doleful but smouldering.

“Yes. I asked Master Rafael what he thought of this German heretic, Luther.”

Rafael smiled, and with that smile, the cherubim and seraphim must surely have fallen into rapture. It was the kind of smile that shouldn’t be permitted on a human face. Zeus would have given Olympus for it; as it is, quite a few titled ladies have given their virtue for it, I gather.

“I’m afraid,” he said sweetly, “I am not a theologically-minded man.”

“It’s nothing to do with theology,” I replied. “It’s a political matter.”

“Oh?” Leo managed to say. “And what do you know about it, you pint-sized cunt?”

“As much as your Holiness does, I think. The German princes are disaffected because they resent the flow of cash making its way to Rome from the sale of indulgences –”

“The preaching of indulgences, you mean.”

“It’s all the same, as Your Holiness well knows. Ever since you came to that arrangement with Jacob Fucker –”

“Fugger! Jacob Fugger!” Leo shrieked, thumping his fist on the table and splattering colchicum sauce all over the place. Fugger was the banker who advanced the new Archbishop of Mayence’s installation and dispensation tax to Leo, and saw to it that half the proceeds from the sale of indulgences in his diocese went into the papal funds; with consummate Hebraic cunning, he persuaded Albert that ten percent of the other half properly belonged to himself, and took it.

“God knows what Albert of Brandenburg wanted with the archbishopric of Mayence anyway. Actually, on reflection, I think the whole thing is economic rather than political.”

Leo threw a half-eaten piece of chicken at me, just missing my right eye with a sharp bone.

“That wasn’t very polite,” I remarked. “You’re embarrassing Master Rafael.”

Merde! I’d been on the winning side, until I forgot myself and spoke that adored name.

“Rafael,” Leo said, moon-struck again. And again, Rafael smiled. He smiled directly at Leo this time, and I might as well have suggested that Luther be the next pope, for all the effect it would have had.

Later, in an expansive mood because Rafael had accepted the invitation to stay the night in the papal apartments, Leo chided me.

“You were very naughty, Peppe. I’ve a good mind to spank you.”

To my horror, I saw a curious speculation dawn in Leo’s eyes, as if he were privately weighing up the pros and cons of actually carrying out this threat.

“Don’t even dare to think of it,” I said.

This morning, I saw Rafael coming out of Leo’s study with a faraway, pondering look on his lovely face, and I thought: I wonder? Exactly what I wondered, was whether or not His Holiness had at last managed to pluck the forbidden fruit. I followed Rafael as he floated dreamily down the corridor like a living canephorus, trying to see if I could detect any tell-tale spots of blood on his hose; this was not too difficult for me, since his small, muscular buttocks were only a foot or so beneath the level of my eyes. After a moment or two however, he sensed my presence behind him, and turned to confront me.

“What do you think you’re doing?” he said.

“Ah. You have such an elegant way of walking, Master Rafael. I was just – well – I thought I might improve my own deportment by imitation.”

He said nothing, but he laid a pale, willowy hand upon my head for a brief moment, then he was gone.

I didn’t see any blood. I’m not surprised really, since everyone knows he keeps a very beautiful mistress. Leo must have slept alone with his futile yearnings.

*

The vignettes I have offered you so far have of course amounted to a portrait of His Holiness Leo X, Giovanni de’ Medici, Successor to the Prince of the Apostles and Holder of the Keys of Peter. I have tried to describe a man who is both a complicated and a simple individual: in his sexual exploits, his political machinations, his humanistic love of art, music and books, and in his mercurial disposition, he is complicated; in his piety, he is refreshingly simple. Somehow he manages to keep these two sides of himself separate, in watertight compartments. For example, he can (and does) spend hours poring over some desiccated old tome dedicated to the propagation of a hermetic doctrine whose heterodoxy makes Mohammed sound like a Dominican by comparison, then trot off happily to Mass; he can rise from his bed in the morning, sore with repeated penetrations by some young lad imported from a miasmal alleyway, then kneel at his prie-dieu in front of an image of the Mother of God, with genuine tears of devotion in his protuberant eyes. I’ve long ago given up trying to make too much sense of it; it’s the whole man, with all his contradictions and paradoxes, that I love. There: I’ve surprised myself by admitting it so explicitly. Yes, poor old Leo, I love him.

Not everyone feels as I do, however; in fact there are (perhaps I should say were, since most of them have been dealt with in typical Medici fashion) quite a few who hate him with a virulent hatred. Last year there was an attempt on his life by several disaffected cardinals, which – fortune be praised! – Leo survived. Actually, it was a rather clumsy effort at poisoning – the old-fashioned method of pest-control popularised by Alexander VI Borgia (now roasting in hell, we all fervently hope) and his murderous brood; you can always find some old hag in a shit-stinking hovel ready to mix a deadly brew for a price. The whole of Rome, they say, is a poisoner’s den, and I for one believe it. His Eminence Cardinal Alfonso Petrucci paid with his life for this abortive attempt to rid the world of Leo; he died, by all acounts, screaming and struggling, blue in the face, all control of his bowels lost, and everyone knew then that the heart which ceased to beat was not only treacherous, but also pusillanimous. His Eminence Cardinal Francesco Soderini (or ‘God’s Sod’ as we all knew him) was fined and imprisoned but later fled, along with Cardinal Adriano Castellesi. A chastened man, Leo introduced a bunch of his own cronies into the sacred College of Cardinals, and everything has been as sweet as roses ever since; of course, this may be due to the perfumed enemas which most of them are in the habit of taking. Cardinal Ridolfi apparently has his scented with lime-flowers.

However, I am mindful that these scribblings of mine do bear the title Memoirs of a Gnostic Dwarf, and hence should primarily be about me; it is therefore my intention to proceed with the story of my life, rather than Leo’s, even though he will inevitably figure prominently in this story. It would not be exaggerating the case to say that I owe everything to him – and I do mean everything. I owe him my daily bread, a roof over my head (and a palatial one at that), money in the bank, status and position, and – above all else – I owe him my dignity. It moves me deeply to write these words.

I will begin with an account of my childhood, and of the chthonic world in which I was obliged to survive; I will relate the adventures that I stumbled into in my older years, my initiation into the Gnostic Brotherhood, and my early life with Pope Leo X – then Giovanni, Cardinal de’ Medici. It never ceases to amaze me how, in such wondrous fashion, the threads of our two lives were drawn together by some invisible and fathomlessly benevolent Will; Leo was made a cardinal when he was a boy of thirteen; at the same age, I was earning a living (if you can call it that) by helping my mother to peddle cheap wine to the scum of Rome. Christ’s blood, how incongruous a marriage of fates can you get?

But I do not wish to anticipate my story; let us begin, as the holy Evangelist John does, in the beginning.

– 1478 onwards –

Deus, qui neminem in te sperantem nimium affligi permittis

In the beginning was not, for me, the Word, but the pain. In the beginning was the pain, and the pain was with me, and the pain was me. It constituted the entirety of my burgeoning consciousness. I knew almost nothing else but this. They told me that as a babe in arms I cried not for my mother’s milk, but for release from pain. This suffering was, I am inclined to think, twofold: at its heart it was both an experience of actual physical pain and also of psychic protest that my soul had been enclosed in such a twisted, malformed, recalcitrant body. My mother and the physician (whose quality of service was proportionate to her capacity to pay, and therefore indifferent), assumed that my suffering resided solely in the agony of crooked bones; they had no idea (and why should they?) that my spirit cried out also, in violent objection. Many years later, after I had been initiated into the Gnostic Brotherhood, I composed some verses to reflect my experience; I would like to share them with you now.

In the beginning was the pain:

the pain was with us, and the pain was in us –

the structure, the frame, the shape of the sound

that spilled from our mouths like blood from a wound,

the only way we knew we were.

In the beginning was vulnerability:

a reason for hiding, crawling away

back to the womb and the uninscribed stone,

to the deep-interred peace, before flesh and bone

knitted together in mute, blind form.

In the beginning was the hurt:

precisely etched on the warp of the heart,

a laid-bare sign, a tell-tale mark

signifying how we had abandoned the dark

and shuffled inexorably into the light.

In the beginning was the motion:

the perpetual rape by shape and form

of wayward spirit, wandering far,

to where the integuments of error are

insistently whispering of sibilant death.

In the beginning shall be a return

to a place where beginnings couple with fire

and, burnt-out, conceive the point

when socket by socket and joint by joint,

the knot of our birthing shall be undone.

Hardly a masterpiece, I know, but it did (and still does) express a little of the philosophy I have made my own, and which has faithfully succoured me as I cross this bridge of sighs we call earthly life. I am proud to say that the Master of our little fraternity has incorporated several of these verses, set to a canorous chant of his own composition, into our liturgy.

My mother once said to me (I suppose she had saved up this little gem of venom, nurturing it like a viper in her bosom, until I was old enough to understand what it meant) when I tried to climb up into her lap:

“God knows, I should have suffocated you at birth.”

There was a time when I would have wholeheartedly agreed with this; now, however, I am rather glad that she did not suffocate me at birth. Strange, isn’t it, how one can always learn to love oneself, however ghastly one is?

I was born in the year of Our Lord 1478, the sixth of the inglorious pontificate of the Franciscan pope, Sixtus IV – by all accounts a man most unlike the gentle founder of his Order, and a successor of Peter whose nepotism makes Leo’s shameless dishing out of favours to members of his family look like casual acts of dispassionate kindness. The house in which I was born was little more than a hovel, in the Trastevere area of Rome; they say that the Trasteverini are the devil’s own, and it’s a view I’m inclined to share: they’re pig-headed, coarse, fiercely independent, and they’re all jackals and rogues to a man. The shit that I leave behind every morning in the papal privy is cleaner and sweeter than some of the scum you come across in Trastevere’s stinking gutters. Certainly, they have no time for anything as sentimental as pity for a deformed child; at least that was my experience. Oh, believe me, I’m not excessively bitter about it – after all, surviving Trastevere life endowed me with the will and instinct to survive almost anything. I was kicked and pelted with rubbish, and abused and beaten up by every bully of a gamin and lazzarone daily. You might claim that this could well have happened anywhere, and you would be right; all I know however, is that it happened to me in Trastevere, and I’ll never forgive it for that. For years now I’ve been pestering Leo to have the whole area flattened and re-built, but he keeps telling me he doesn’t have the money. This is quite true, but it doesn’t stop me pestering him.

My mother had been widowed after just two weeks of marriage to a neighbour’s son, in the most grotesque of circumstances: the man who did not live long enough to become my father was sleeping in the hot afternoon sun outside Santa Maria in Trastevere, after a drunken binge with his cronies; he must have turned carelessly and grazed his ear or his cheek – at any rate, there was blood somewhere – and a pack of crazy stray dogs ate half his face away before someone managed to drive them off. He died of shock a day later. My mother said to everybody:

“He was gobbled up by his own kind.”

My mother sold wine, tramping the streets with a wooden cart loaded with demijohns of sour, vinegary gut-rot which she occasionally managed to mix with a little Frascati. God only knows who my biological father was. I later learned that I was conceived as the result of a brutal act of rape, so I suppose he could have been anyone who goes in for that sort of thing.

“I couldn’t fight him off,” my mother said, when she finally got round to telling me the unedifying story of my genesis.

“Why? If you’d beaten him off, I wouldn’t have been born.”

“He was too strong for me. Besides, I was pissed at the time.”

“Who was he? Would you know him again if you saw him?”

“Know him? I’d know him in the darkness of hell itself, which is where I hope he is now, the cockless bastard.”

If this description was in any way accurate, my unknown progenitor must have suffered his de-cocking subsequent to my conception, I presume; however, I suspect it was just wishful thinking on my mother’s part. She was much given to that sort of imaginative rhetoric. In fact, coming across a particularly belligerent or tight-fisted customer, she would often set her colourful little predications to song:

Don’t your balls hang low?

Did your cock never grow?

Oh, if all the ladies knew

Just what I know of you!

“Who was my father?” I persisted. “Who was he?”

“Mind your own sodding business.”

And that was that.

As soon as I was old enough – I was never really able, but I managed somehow – I accompanied my mother on her rounds, and relieved her by pushing the cart, which was wondrously heavy. I did it by placing my hump against the back of it, between the handles, and walking backwards. Sometimes my twisted, stunted legs buckled under me and I fell, and inevitably one of the demijohns (usually a full one) came sliding down onto my head. With equal inevitability, my mother would shriek: “Thank Christ it was only your sodding head!” and burst into peals of laughter which were all the more cruel because they were absolutely genuine. Once, when an empty demijohn actually shattered against my skull, she laughed so much she wet herself. There she stood in the middle of the street, her beefy hands on her hips, her legs apart, a stream of hot, steaming piss running down her shins onto the cobbles, her head thrown back as she shook with guffaws; and I thought: This is not my mother. It was as simple as that – an instant, conscious, sober decision, and from that moment until this (she may be dead, for all I know) she has been as alien to me as a straight spine. If I refer to her as my mother in the pages which follow, it is only for the sake of literary convenience, and to save myself the trouble of inventing an epithet more accurate, if less charitable.