19,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Ventil Verlag

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Deutsch

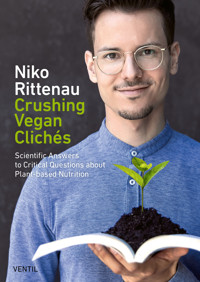

"Crushing Vegan Clichés" dispels the most common myths about vegan diets. Based on scientific research, but written in an easily understandable way, the book answers important questions about the supply of essential nutrients such as protein, iron, calcium, B12, omega-3 and others. With the right choice and preparation of foods, a vegan diet can be healthy and effective in preventing chronic degenerative diseases – and this guide shows what is important. It explains why some nutrition societies recommend a vegan diet for all age groups, while others advise against it. The book's practical approach shows how to meet daily nutritional needs with a vegan diet based on a wide range of plant-based foods. It objectively examines the truth behind common stereotypes and refutes them when necessary. Does soy really contain estrogen, which "feminizes" men and promotes breast cancer in women? Is too much fructose from fruit bad for you, and do high-calorie nuts make you fat? Is gluten in cereals harmful and what is the truth about the alleged toxic anti-nutrients in legumes? All these and many more myths are explained objectively and non-dogmatically. "Crushing Vegan Clichés" demystifies many of the assumptions about vegan diets, but also offers new insights for people who live vegan. Translated into English by Justin P. Moore & Sarah Pybus

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 993

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Webwww.nikorittenau.com

Youtubewww.youtube.com/nikorittenau

Instagramwww.instagram.com/niko_rittenau

Facebookwww.facebook.com/niko.rittenau

Berlin-based Niko Rittenau is a nutrition expert focused on plant-based nutrition. He combines his culinary skills and solid knowledge of nutritional science from his academic studies to innovate and inspire, bringing together great taste, health awareness, and sustainability.

In lectures and seminars he illuminates his vision of responsible dietary choices with a focus on wholesome foods to appropriately nourish a rapidly-growing world population. Niko has a bachelor’s degree in Nutritional Sciences and a master’s degree in Micronutrient Therapy and Holistic Medicine.

Niko Rittenau

Crushing Vegan Clichés

Scientific Answers to Critical Questions about Plant-based Nutrition

Parts of this book refer to the results of studies involving animal experiments. The author and publisher wish to emphasize that this is in no way an endorsement of animal testing. For more information concerning cruelty-free research methods, please consult Doctors against Animal Experiments (Ärzte gegen Tierversuche e.V.)

From a legal perspective, it must be noted that the information in this book is in no way intended as a substitute for medical advice or medical treatment. All statements in this book have been extensively researched and chosen with the best of knowledge and intention to provide an objective, accurate representation of current scientific understandings. Because nutritional scientific findings are constantly being revised and improved, despite every effort to keep the information of this book up-to-date, no absolute guarantee can be issued. Corrections and current updates concerning the content of this book can be found at: www.nikorittenau.com/vka-update

The information in this book is based on the scientific findings of many pioneers of nutritional science and nutritional medicine and is offered with extreme gratitude for these individuals and respect for their work. At the end of the book is a list of those who most influenced this book and to whom the author wishes to express thanks.

1st English edition 2024

Translated into English by Justin P. Moore & Sarah Pybus

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form, by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical—without prior written permission of the publisher and author, except by a reviewer, who may use brief excerpts in a review.

Original Title: Vegan-Klischee Ade—Wissenschaftliche Antworten auf kritische Fragen zu veganer Ernährung

© Ventil Verlag UG (haftungsbeschränkt) & Co. KG, Mainz 2018

Edition Kochen ohne Knochen

eISBN 978-3-95575-638-3

Design & Layout: Oliver Schmitt

Cover photograph by Claudia Weingart

(Image editing: Moritz Thau)

Ventil Verlag, Boppstr. 25, D-55118 Mainz

www.ventil-verlag.de

Contents

Foreword by Dr. Melanie Joy

Introduction

What do dietary and health organizations say about vegan diets?

Vegan diets during pregnancy and lactation

Why doesn’t the German Nutrition Society (DGE) recommend a vegan diet?

Not all vegan diets are complete and nutritious

Optimum vegan nutrition

Protein

The basics of protein

Determining protein requirements

Do vegans get enough protein?

Plant-based protein sources

Plant-based protein vs. animal protein

Protein deficiency and calorie deficiency

Optimizing protein intake

Ranking Proteins

Combining Proteins

Protein recommendations for vegans

Minimum and maximum protein intakes

Summary

Omega-3 fatty Acids

Further down the food chain

Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids for heart and brain health

The correct dosage of omega-3 fatty acids

The interaction of Omega-3 and Omega-6 fatty acids

Optimizing the body’s synthesis of long-chain Omega-3 fatty acids

Summary

Vitamin B12

Staying true to nature

The basics of B12

Recommended daily B12 intakes

A brief exploration of human anatomy

The history of vitamin B12

B12 and self-sufficiency

Fortifying plants with vitamin B12

At risk of deficiency

Staying safe: The right test

Dietary supplementation: Which supplement and how much?

Different forms of B12

Determining daily B12 intakes

Does vitamin B12 contribute to skin trouble?

Does too much vitamin B12 cause cancer?

Summary

Vitamin B2 (Riboflavin)

The body’s vitamin B2 requirements

Plant-based foods containing vitamin B2

Summary

Vitamin D

The body’s synthesis of vitamin D

Optimizing vitamin D intake

Supplementing insufficient production

Correcting vitamin D deficiencies

Minimum and maximum intakes

Vitamin D3 or Vitamin D2?

Vitamin D3 and Vitamin K2: An optimal combination?

Summary

Iron

The body’s iron requirements

Recommended iron intakes for vegans

Plant-based sources of iron

Optimizing iron absorption

Too much of a good thing?

Summary

Calcium

Calcium and other nutrients for bone health

The body’s calcium requirements

Minimum and maximum calcium intakes

Recommended calcium intakes for vegans

Plant-based sources of calcium

Optimizing calcium absorption

Summary

Zinc

The body’s zinc requirements

Recommended zinc intakes for vegans

Plant-based sources of zinc

Optimizing zinc absorption

Summary

Selenium

Selenium and health

The body’s selenium requirements

Minimum and maximum selenium intakes

Recommended selenium intakes for vegans

Plant-based sources of selenium

Summary

Iodine

Iodine and thyroid health

The body’s iodine requirements

Minimum and maximum iodine intakes

Plant-based sources of iodine

Iodized salt

Recommended iodine intake for vegans

Too much of a good thing?

Summary

The five most important food groups for vegan nutrition

Whole Grains

Agriculture—Off to a rough start

Grains for brains

Stone-age genetics and modern nutrition

Shrunken by grains?

Do carbs cause obesity and diabetes?

Is gluten hazardous to health?

Gluten sensitivity and wheat allergies

Inflammatory reactions to wheat among healthy individuals

Summary

Legumes

The second-meal effect

Anti-nutrients—friend or foe?

Bypass the gas

How to cook legumes

Summary

Vegetables

Not all vegetables are equal

Vegetables and how to cook them

Raw food and human evolution

How to cook cruciferous vegetables and bulbous plants

Cruciferous vegetables and thyroid health

Summary

Fruit

Fructose and weight gain

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Fructose malabsorption

Smoothie, juice, or whole fruit?

Summary

Nuts and Seeds

Do nuts make us fat?

The mechanisms behind disappearing calories

Nuts: A superfood

Flaxseeds: Little seeds that pack a punch

Do nuts and seeds need to be soaked?

Nuts and aflatoxins

Summary

The Soy Controversy

Soy

Soy and the destruction of the rainforest

Genetic engineering in soy cultivation

Who should avoid soy?

Misconceptions about soy

Claim: “Soy causes breast cancer.”

Claim: “Soy feminizes men.”

Claim: “Soy disrupts thyroid function.”

Claim: “Soy impairs children’s development and sexual maturity.”

Claim: “Soy promotes the development of Alzheimer’s.”

Summary

Everyday advice for vegan nutrition

Adapting the DGE guidelines to a vegan diet

DGE nutritional circle and food pyramid for vegans

Meeting essential nutrient requirements

Why some vegans should take vitamin A supplements

Vegan diets are easy—an example

Summary

Afterword by Dr. Markus Keller

Appendix

Index of illustrations and tables

References

Image Credits

Foreword by Dr. Melanie Joy

It is with pleasure that I write this foreword for CrushinG Vegan Clichés. This book provides essential information for taking the vegan movement to the next level. It gives both vegans and non-vegans the tools to transform the way they think about nutrition and thus the way they eat. It empowers vegans to eat more healthfully and to therefore be more effective ambassadors for the cause, and it invites non-vegans, who may have distrusted the nutritional soundness of a vegan diet, to reconsider their assumptions and to move toward a more vegan way of life.

Crushing Vegan Clichés is a much-needed addition to the nutritional literature. Most existing books on nutrition are written by those who, albeit unwittingly, studied their science in institutions that are influenced by an invisible bias. This bias distorts perceptions of nutrition in general and makes full understanding and appreciation of vegan nutrition impossible. Niko Rittenau is one of the few nutritional scientists who is not only aware of this bias, but who has undertaken his studies specifically to highlight and challenge it.

The bias I write of comes from carnism. Carnism is the invisible belief system that conditions people to eat certain animals. It is essentially the opposite of veganism. Most of us assume that only vegans (and vegetarians) follow a belief system when it comes to eating animals. But the only reason we learn to believe it’s okay to eat pigs but not dogs, for example, is because we do follow a belief system when it comes to eating animals. When eating animals is not a necessity, which is the case for many people in the world today, then it is a choice. And choices always stem from beliefs.

We don’t recognize carnism for what it is because the system is structured to maintain its invisibility and to prevent us from questioning why we eat certain animals but not others—or why we eat any animals at all. Carnism is a violent system, meaning it’s organized around violence. Most people would never willingly support intensive, extensive, and utterly unnecessary violence toward animals, and so they need to be coerced into participating in such a system. Carnism provides us with the tools to do just that, in large part by providing us with a host of myths that teach us to believe that eating animals is the right thing to do—that eating animals is normal, natural, and necessary. Carnism also provides us with myths that teach us to believe that not eating animals is the wrong thing to do—that veganism (and by extension vegans) is abnormal, unnatural, and unnecessary.

The myths of carnism are institutionalized: they are embraced and maintained by all major social institutions, such as psychology, education, and, yes, nutrition. So when people study nutrition, they actually study carnistic nutrition. (The reason vegans are often accused of being biased when discussing nutrition is simply because the dominant, carnistic bias remains invisible.)

What Niko Rittenau has done with Crushing Vegan Clichés is to expose and challenge some of the nutritional myths of carnism that prevent vegans and non-vegans alike from obtaining solid, scientific nutritional information. For vegans, this means they now have a guide to help them eat more healthfully, so that they can treat their bodies and the bodies of those they feed with the same respect with which they may ask others to treat animals. For non-vegans, this means they can open their minds to vegan philosophy without worrying that if they decide to become vegan, or to move toward veganism, they won’t be healthy.

Thankfully for all of us, Niko Rittenau has spent years studying the scientific literature, and practicing what he’s learned, to put together this comprehensive guide on vegan nutrition. I’m grateful that this book exists, and optimistic that the new editions will continue to fly off the shelves. And I’m hopeful for the potential of this book to help bring about a widespread shift in how we all think about vegan nutrition.

Melanie Joy, PhD

Author of Why We Love Dogs, Eat Pigs, and Wear Cows

Introduction

Although an abundance of scientific publications and a succession of advisory statements from dietary and health organizations worldwide have in recent years shown that a well-planned vegan diet is adequate for all stages of the life cycle, a multitude of clichés and myths persist regarding the healthfulness of an entirely plant-based diet. A vegan diet is not a solution to all of the world’s problems, nor is it the miracle cure it’s often proclaimed to be. It is, however, a simple and efficient way to combine environmental and animal welfare concerns with healthful eating habits. This book does not seek to demonstrate that a vegan diet is ultimately ideal from every conceivable nutritional and physiological standpoint. Rather, it intends to dispel critical concerns regarding a vegan diet with evidence-based research and to address an assortment of established misperceptions within the vegan community which pose a threat to the health of those following a vegan diet.

This book relies on current scientific literature to show that an entirely plant-based diet is adequate and healthful. We’ll go a step further and investigate the criticisms of vegan diets and clarify how misinterpretations of the dietary scientific data have led these myths to arise. This book was written with the intention of providing a handbook with which individuals following a vegan diet are assisted in making the best possible dietary choices for themselves and their families. The book is also meant for anyone interested in understanding the essentials of dietary scientific findings pertaining to the many aspects of plant-based diets. Additionally, it is intended for those who still find themselves skeptical of vegan diets, and it aspires to respond to and resolve remaining doubts.

The first part of the book examines critical nutrients of a vegan diet and explores how to optimally meet dietary requirements with a plant-based diet. The second part of the book is dedicated to the five main food groups which comprise a wholesome, nutritious vegan diet. Numerous concerns about these foods will be addressed and their validity checked. We’ll also deal with the soy controversy, discuss the origins of many myths regarding soy, and consider recent studies and current medical positions of leading dietary, health, and cancer associations to counter and correct these misconceptions.

What do dietary and health organizations say about vegan diets?

Even though there are still many dietary and health organizations that have yet to take a definitive position on vegan nutrition, in the last few years there have been a considerable number of publications from around the world which address the topic and report positively about vegan diets in all stages of the life cycle. However, in 2016 the German Nutrition Society (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ernährung—DGE) announced a position challenging the nutritional and physiological validity of plant-based diets:

“With an exclusively plant-based diet it is difficult or impossible to attain an adequate supply of some nutrients. The most critical nutrient is vitamin B12. Other potentially critical nutrients for a vegan diet include protein (specifically, essential amino acids and long-chain omega-3 fatty acids) as well as other vitamins (riboflavin, vitamin D) and minerals (calcium, iron, iodine, zinc, and selenium). The DGE does not recommend a vegan diet for pregnant women, lactating women, infants, children, or adolescents.”1

The Swiss Nutrition Society (Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Ernährung) issued a press release stating they do not recommend a vegan diet for the general public and that above all children and pregnant and lactating women must pay close attention to meeting nutritional requirements.2 The Austrian Nutrition Society’s statements regarding vegan diets have reflected the criticisms of the DGE as well as the overwhelmingly positive position stated by the American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND). They have maintained a relatively neutral view on vegan diets, mentioning potential health advantages along with disadvantages.

Because in the course of informing themselves people often just read the summaries of published statements such as those from the DGE, it is hardly surprising they interpret the viewpoint as critical and in opposition to a vegan diet. At the same time, individuals actively following a plant-based diet may read these statements and feel justified to entirely dismiss the work of the DGE. It would actually be wise for both sides to read the publications in full, as they would probably be surprised by the entirety of the information. Despite the rather unfortunate formulation of the summary, the article’s authors actually did a very decent job overall and provide a comprehensive review of vegan dietary research which is certainly more positive than the summary suggests.3

From the DGE: “It can be assumed that a plant-centered diet (mostly or entirely excluding meat) is associated with a lower risk for diet-related diseases when compared to the current, typical German diet.”4 Additionally, they state “…with intentional food choices and proper planning it is possible to structure a vegan diet in which no nutrient deficiencies develop.”5 The authors write that any diet which does not adequately provide critical nutrients and energy can negatively affect health, and followers of such diets must intentionally plan food choices accordingly. According to the DGE’s published statement, for a vegan diet to be nutritionally adequate there are three key requirements, each of which are manageable for most vegans:

•regular and consistent use of a B12 supplement and routine medical evaluation of B12 levels

•intentional selection of nutrient-dense and fortified foods to prevent deficiencies of critical nutrients

•an individualized consultation with a qualified nutritional professional to understand the basics of the diet

In their statement, the DGE references studies which mention the possibility that vitamin B12 can be found in certain types of algae and in products fermented with the correct bacteria. However, they strictly advise against trusting these unreliable sources for meeting dietary requirements. This agrees with the guidelines of other organizations and health professionals who likewise explicitly advise the use of B12 supplements and fortified foods, as we will explore in detail in the chapter on vitamin B12. This recommendation is not only meant for vegans; The National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the USA advise supplementation for all individuals over the age of 50, regardless of their dietary choices, to compensate for decreased B12 absorption from food sources as age increases.6 The DGE’s second requirement, intentional nutrient-dense food selection assisted by moderate supplementation, is beneficial for followers of many diets—including vegans—in their quest for everyday proper nutrition. In addition to an adequate supply of micronutrients, providing sufficient calories should also be a focus.

The DGE’s third requirement for an adequate vegan diet is for proper, specific advice from a professional. The need for this information was one of the guiding reasons for writing this book and also inspired the creation of my nutritional seminars, which several times a year provide the necessary know-how for adequate plant-based nutrition during all stages of the life cycle.

We can see that the DGE’s objections to a vegan diet for adults are actually relatively minor. This isn’t surprising, given that a wholesome vegan diet provides similarly adequate coverage of the DGE’s recommendations. Figure 1 shows the percentage breakdown of various foods of the DGE standard nutrition guide compared to that of a vegan diet, showing a high degree of overlap between both diets.

Figure 1: Comparison of the DGE Food Guide and Vegan Plate7,8

The vegan plate is nearly 75 % identical to the standard food guide. Meat, fish, eggs, and dairy are replaced with legumes, nuts, and seeds—and a vitamin B12 supplement is included.

As evidenced in Figure 1, the DGE advocates a diet which is about 75 % plant-based. Their article, Nutritious Eating and Drinking—10 Rules of the DGE refers to the amount of animal and plant foods included in an ideal diet: “Choose predominantly plant-based foods.”9 Quantitatively, the DGE food guide recommends about 30 % whole grains, 26 % vegetables, 17 % fruit, and 2 % additional fats and oils.10 According to the DGE, the fats and oils can be of either animal or plant origin, but the recommendation is clear: “Choose predominantly vegetable oils such as canola oil and margarines made from such.”11 Still remaining is 7 % meat, fish, and eggs, as well as 18 % dairy products.12 The DGE addresses the similarity between their official recommendations and those of a vegan diet: “A comparison of a nutritious diet as recommended by the DGE and the recommendations for a vegan diet according to the Gießener Vegetarian Food Pyramid reveals that the basis between each is equal and the food-specific recommendations are very similar.”13

The authors of the article state that this 25 % of animal products can be replaced by plant-based foods as long as the vegan alternatives are equally capable of providing the critical nutrients which otherwise would be supplied by the animal foods.

Vegan diets during pregnancy and lactation

The concerns of the DGE relating to vegan diets are not especially directed at the general population, but instead concentrate primarily on specific groups of individuals with increased nutritional needs, such as pregnant and lactating women and children. The ultimate conclusion of the authors is justified in part by incomplete research and information pertaining to the segments of the population. Despite limited findings, a systematic overview study from 2015 determines that a properly planned vegan diet during pregnancy can be viewed as safe and adequate.14

Differing stages of life have differing nutritional needs. Especially during pregnancy and lactation, a strong focus on appropriate and adequate nutrition is necessary. Figure 2 shows the nutrients critical in vegan diets along with the increased needs during pregnancy and lactation.

As we see in the diagram, requirements for varying nutrients during pregnancy and/or lactation are increased. These increased needs must be met with nutrient-dense foods. Specifically, folate is a critical nutrient in conventional western diets which can be supplied significantly better with a wholesome, plant-based diet.

Figure 2: Nutritional requirements for women during pregnancy and lactation15,16

Because of folate’s crucial importance during pregnancy, it has been included in Figure 2. The other nutrients shown refer specifically to a vegan diet—although iodine, for example, can often also be deficient on an omnivore diet.

Regarding infants, breast milk is the ideal food for the first half year, so the question of dietary choice isn’t generally relevant.17 Breastfeeding is the optimal source of nutrition during infancy. A mother with balanced nutrition fully provides the nutritional needs of a healthy infant in the first six months of life.18 To ensure adequate and ideal nutrition for an infant following a vegan diet, the Portuguese nutrition organization Direcção-Geral de Saúde (DGS) recommends that beyond an initial six months of exclusively breastfeeding, breast milk should continue as a complementary source of nutrition for vegan babies along with introduced foods until two years of age.19 Although the DGE still (current as of September 2020) does not recommend a vegan diet for pregnant and lactating women or adolescent children, there is a number of international health and nutrition organizations which have examined the available scientific dietary findings and determined that a vegan diet—if properly planned and balanced—is adequate for all stages of life. Figure 3 summarizes the positions of nutrition agencies in the USA, Canada, Australia, Great Britain, and Portugal.

The statements of the dietary organizations clearly state that a vegan diet at any stage of life can meet all nutritional requirements—as long as parents observe several nutritional guidelines regarding children’s diets, all of which we will discuss in detail in the course of this book. In late 2017, the British Dietetic Association went a step further and announced a partnership with the Vegan Society of England to “show that it is possible to follow a well-planned, plant-based diet that supports healthy living in people of all ages, and during pregnancy.”20 The cooperation between a recognized dietary organization and a vegan association and the resulting conclusions emphasize that the scientific facts indicate that a well-planned vegan diet can indeed fulfill all bodily nutritional requirements. In their position paper, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND) express their agreement with other organizations that properly planned vegan diets are not only safe and adequate for all stages of life; by means of the increased intake of fruit, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds they also reduce the risk of chronic, degenerative diseases.21

Figure 3: International Dietary and Health Organizations and their position on vegan diets22,23,24,25,26

Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND), USA 2016

“It is the position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics that appropriately planned vegetarian, including vegan, diets are healthful, nutritionally adequate, and may provide health benefits for the prevention and treatment of certain diseases. These diets are appropriate for all stages of the life cycle, including pregnancy, lactation, infancy, childhood, adolescence, older adulthood, and for athletes.”

Direcção-Geral de Saúde (DGS), Portugal 2015

“When appropriately planned, vegetarian diets, including lacto-ovo vegetarian or vegan, are healthy and nutritionally adequate for all cycles of life, and they can be useful in prevention and treatment of some chronic diseases.”

Dietitians of Canada (DC), Canada 2014

“A healthy vegan diet has many health benefits including lower rates of obesity, heart disease, high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol, type 2 diabetes and certain types of cancer. […]A healthy vegan diet can meet all your nutrient needs at any stage of life including when you are pregnant, breastfeeding or for older adults.”

National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC), Commonwealth of Australia 2013

“Appropriately planned vegetarian diets, including total vegetarian or vegan diets, are healthy and nutritionally adequate. Well-planned vegetarian diets are appropriate for individuals during all stages of the life cycle. Those following a strict vegetarian or vegan diet can meet nutrient requirements as long as energy needs are met and an appropriate variety of plant foods are eaten throughout the day.”

British Nutrition Foundation (BNF), UK 2005

“A well-planned, balanced vegetarian or vegan diet can be nutritionally adequate […]. Studies of UK vegetarian and vegan children have revealed that their growth and development are within the normal range.”

Why doesn’t the German Nutrition Society (DGE) recommend a vegan diet?

When we consider that all dietary organizations have access to the same nutritional literature and scientific studies, it’s somewhat surprising that various international institutions have come to conflicting conclusions. The reason for this is certainly not disagreement among dietary professionals nor insufficient data. The cautionary recommendations in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland—in contrast to countries such as the United States, Canada, and Great Britain—are in part due to varying availability of foods fortified with critical required nutrients, as well as varying mineral content in the soil of each country. Consequently, fruit and vegetables in Germany have quite different vitamin and mineral content than North American produce.

It is much more common in the United States to fortify foods with the vitamins which are often deficient on a vegan diet. As a result, vegans in the United States consuming enriched plant-based milks and yogurts, and other fortified plant-based products are supplied daily with adequate vitamin B12, for example, without relying on supplementary sources. This makes a critical difference. In Germany, if you don’t make an active effort to obtain B12, there are unfortunately few sources which provide it to you.

According to EU regulations, the fortification of organic products with additional vitamins is expressly prohibited.27 Consequently, it’s not really possible in Germany and Austria to find organic plant-based milks and yogurts which are enriched with B12. In contrast to the United States, in Germany it is therefore necessary to actively source vitamin B12 from nutritional supplements. Regulatory exceptions are worth considering for fortifying plant-based milk and yogurt alternatives to enable vegans to obtain adequate B12 from consuming organic products. The selection of enriched conventional (non-organic) products is also comparatively poor. This is one of many important factors in understanding the conflicting recommendations between countries.

The second reason for differing recommendations regarding vegan diets bring us back to the considerable differences in soil mineral content of varying regions. In Germany, Austria, and several other European countries, soil contains significantly less selenium, for example, than in the United States and Canada.28 Due to selenium-rich soil, North American whole grain products and legumes are decent sources of selenium. In Germany, these products usually contain an insignificant amount of selenium. Grains analyzed in the United States contain up to 100 micrograms (µg) of selenium per 100 grams, whereas grains in Germany have been determined to average less than 5 micrograms (µg).29 Selenium is a critical nutrient for vegans in Germany, because of the mineral’s scarcity in German soil.30

Omnivores in Germany also have an advantage—A selenium-rich mineral compound is used with livestock feed to guarantee a constant level of selenium in meat, eggs, and dairy products. In the European Union, it is permitted for animal feed to be fortified with up to 500 micrograms (µg) per kilogram.31

There is a definite distinction regarding how vitamins, especially as with vitamin B12, and minerals such as selenium, are provided, which explains several of the differences in the recommendations. Regions with low selenium levels would be extremely wise to follow Finland’s example and ensure that soil is appropriately enriched with mineral fertilizers containing selenium instead of fortifying livestock feed. Starting in 1984, Finland began to methodically enrich the soil with selenium, and remains to this day the only European country which follows this strategy.32 Systematic fortification has increased selenium levels of wheat in Finland by a factor of ten. The amount of selenium in several vegetables such as onions, garlic, and broccoli have been elevated more than a hundred fold.33 Germany would certainly benefit from adopting similar measures.

Looking over the collection of position papers and published findings in dietary literature, the majority show that a well-planned vegan diet is nutritionally adequate for all stages of life and brings with it numerous health advantages over a conventional western diet.34 The main reason why a vegan diet is not universally recommended for all segments of the population in every country has little to do with impracticality. The concerns of several organizations have far more to do with limited dietary understanding of the general public due to a lack of teaching nutrition in schools and a lack of responsible, quality reporting about nutrition in the media. Many people are more interested in their car than their body and usually devote more time and attention to their car. But the fact that the average German typically knows more about their mobile phone than their nutritional needs does not necessarily imply the same is true for individuals following a vegan diet. According to a survey from the Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (Bundesinstitut für Risikobewertung—BfR), vegans typically have a well-above average understanding of nutrition.35 The BfR emphasizes that followers of most forms of plant-based diets make a considerable effort to best inform themselves about nutrition. The vast majority of vegans are aware of the need for a reliable source of vitamin B12, which nutrients are potentially lacking in a plant-based diet, and many other diet-related matters.

Not all vegan diets are complete and nutritious

Although dietary organizations generally agree that we should be eating a lot more plants and far less animal products, the collection of scientific findings about plant-based diets is somewhat varied. Vegans don’t always come out better than omnivores in all studies. In order to arrive at valid, scientific conclusions, it would be ideal to rely on an extensive range of intervention studies conducted involving control groups, precisely set meal plans, and a study design which eliminates any speculation about participants’ dietary and lifestyle habits. Unfortunately, such dietary studies are difficult to conduct because extended time periods of observation are inevitably required to determine medium and long-range effects and because so many factors influence long-term health. Attempts to evaluate the health effects of just a single nutrient or particular type of food can result in contradictory findings. Errors and inaccuracies are even more common when comparing entire diets from different groups. For research purposes, a concise definition of a vegan diet is problematic as the only mandatory criterium for a vegan diet is that it excludes animal products. This of course includes a diverse range of eating habits. The diets themselves may be very healthy, or conversely, unhealthy. In today’s world we have access to all sorts of unhealthful fast food, junk food, sweets, and beverages—for most of which vegan versions are available. This makes it easy to mimic conventional western diets with entirely plant-based foods which aren’t any more healthful than their non-vegan counterparts. Just as important as the definition of what a vegan diet excludes would be a concise definition of what a healthy plant-based diet includes, and which products may well be vegan, but also detrimental to health.

Many people decide to become vegan primarily for ethical reasons and might not be focused on having a complete and nutritious diet. Such a vegan diet may include highly processed products, white flour, sugar, excessive amounts of salt, and trans fats. Conversely, other individuals choosing a vegan diet are predominantly motivated by its health advantages and consume whole grains, legumes, fruit, vegetables, and nuts, and are mindful of critical nutrients.

Both groups of vegans are lumped together in studies although their eating habits and lifestyles are completely different.36 This inevitably leads to the negative impacts of a junk food vegan diet being moderated by the health-conscious vegans of the group, and the health benefits of a proper plant-based diet are likewise negated by the group’s junk food vegans. Future studies should not only distinguish between vegan, vegetarian, and omnivore diets, but also between the nutritional qualities of the diets followed by participants.37

This is why it’s not surprising that a vegan diet doesn’t always perform as well in studies as would be expected. For example, if we compare the eating habits of the vegans participating in the Adventist Health Study (AHS-2) with those of the EPIC Oxford Study we clearly see that the latter group had on average considerably lower intakes of dietary fiber and vitamin C caused by including fewer fiber-rich whole grains and legumes, and less fruit and vegetables high in vitamin C.38 The phenomena of motivations dictating eating habits is also reflected in vegetarian diets. This also explains why the more health-conscious vegetarian Adventists evidenced longer life expectancies and lower rates of colon cancer when compared to the omnivores, which couldn’t be reflected in British vegetarians of the EPIC Oxford study.39

It’s also important to note that many people have unhealthy eating habits for decades before becoming more health-conscious. Chronic diseases develop over the course of years or decades and can arise well after a healthier diet has been adopted. On the other hand, a disease often causes an individual to reflect on their diet and lifestyle and improve both. Such limitations need to be considered when evaluating findings on vegan diets.

To describe a healthy diet which is nutritious in addition to being vegan we can use the term “whole-food plant-based diet”.40 Even among whole-food plant-based diets we can make further distinctions as a whole-food plant-based diet is not always abundant in nutrients. Dr. Joel Fuhrman’s nutritarian diet is an example of a whole-food plant-based diet which puts special emphasis on foods with a decent ratio of calories to nutrients.41

Whatever words we choose, the bottom line is that every healthy, purely plant-based diet is a vegan one, but not every vegan diet is complete, healthy, and nutritious. Our goal should be to not only protect animals and the environment with our food choices, but our own health as well. This objective isn’t possible with a diet which simply imitates unhealthy conventional, western eating habits with vegan foods. We need a wholesome vegan diet which completely rethinks our meals: more whole grains instead of white flour, fruit rather than refined sweeteners, protein-packed lentils and beans instead of protein isolates, fewer isolated fats and more healthy fats from nuts, seeds and other nutritious foods.

Optimum vegan nutrition

Even though publications including that of the German Nutrition Society (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ernährung — DGE) speak of “critical nutrients” of a vegan diet, these nutrients are not always critical in every vegan diet. It just means that these nutrients can potentially be deficient with the typical food choices of many followers of vegan diets. There is actually a whole range of plant foods that reliably provide the required amount of each of these nutrients.

Figure 4: Critical nutrients of a vegan diet rated by severity1

The DGE’s position paper lists potentially critical nutrients of a vegan diet. However, these nutrients are not equally critical. Figure 4 addresses the differences and depicts how comparatively difficult it is to obtain each of these nutrients on a plant-based diet.

Starting with vitamin B12 (the most critical nutrient) at the center and moving outwards, the diagram shows the increasing ease of meeting each nutrients’ requirements on a vegan diet. The further out, the easier to meet, and the less critical the nutrient. All other nutrients not depicted in this diagram are considered by the DGE and other dietary organizations to be adequately and reliably provided by a well-balanced vegan diet of sufficient calories. In the course of this book, I’ll also show how all of these critical nutrients can be entirely supplied by our food intake. In practice however, it’s safer and more practical to get critical nutrients—such as vitamin B12—with nutritional supplements, because plant-based food sources either haven’t been researched adequately, or aren’t as readily available to everyone.

Each of the nutrients listed in Figure 4 will be presented and explored in detail in this book. We’ll look at why they are critical, which plant foods are the best sources, and other points of consideration. Notwithstanding the importance of a well-planned vegan diet, we should be able to follow a diet that is enjoyable, practical for every day, and enriches our lives—without making it all too complicated and taking away from the joy of eating.

Although dozens of vegan athletes around the world are breaking records in a variety of sports, some publications still mistakenly associate vegan diets with decreased strength, endurance, and performance as well as insufficient protein. However, successful athletes have proven that even after years of following entirely plant-based diets, physical strength isn’t compromised. Vegan strongman Patrik Baboumian, as an excellent example, set the world record in 2013 for the Yoke Walk by carrying 555 kg for over ten meters.1 There’s also Ultramarathon runner Scott Jurek, who has followed a vegan diet since 1999. Jurek has broken many records, including winning the Western States Endurance Run (160 km) seven times in a row.2

Obviously these isolated examples are not evidence-based proof of the benefits of a vegan diet, but they definitely add another dimension to discussions within scientific literature regarding protein requirements of vegan athletes. Hundreds of other athletes also demonstrate that it works not only in theory, but also in practice. Since the DGE lists protein as a critical nutrient for vegan diets,3 we’ll explore in detail how a vegan diet can provide adequate, quality protein. We’ll also see in which circumstances an entirely plant-based diet could indeed be deficient in protein.

The basics of protein

The word protein comes from the Greek word proteios which means “first” or “primary”. The origin and naming of the word gives us insight into how nutritional science has viewed protein since its discovery. The most important function of protein is building tissue in the body, but it’s also used by the body for many other tasks. Dietary protein in the human body is made of about twenty amino acids, only eight of which cannot be made by the body itself. These eight amino acids are therefore “essential” (to survival) and must come from dietary sources.4 There are a few other amino acids that in certain circumstances are essential and are therefore termed “conditionally essential” or “semi-essential”. The amino acid histidine, for example, is listed as a ninth essential amino acid in some publications and only as semi-essential in others. It’s not essential for adults, but is for infants. All of the other twenty relevant amino acids are not essential as they can be made by the body, provided that all materials needed are supplied by the diet. Ultimately, it’s actually not protein itself which is important to the body, but just certain amino acids.5 Since these are generally consumed as dietary protein and not in isolated form, we’ll be talking about protein requirements.

The eight essential amino acids are phenylalanine, isoleucine, lysine, valine, methionine, leucine, threonine, and tryptophan. In order to ensure an adequate supply of all of these amino acids, there are officially established recommended intakes for each. However, the suggestions in this chapter for meeting dietary protein requirements with the right plant foods will allow us to focus on overall protein intake without needing to concern with individual, separate recommended intakes.

Determining protein requirements

According to the DGE, the official recommended daily intake of protein is 0.8 grams per kilogram of ideal body weight.6 This agrees with the recommendations of many other dietary and health organizations, including that of the World Health Organization (WHO), which suggests a daily intake of 0.83 grams of well-digestible protein per kilogram of body weight.7 Overweight individuals should calculate their daily protein requirements based on their ideal, healthy body weight, not their actual weight, in order to avoid overestimating protein requirements. Ideal weight is determined with a variety of methods including the Broca index or Hamwi formula, or by using standardized gender-specific charts.8 The official recommendation of 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight has a safety margin calculated into it to account for individual variations. Accordingly, these values should be accepted as optimal intakes rather than absolute minimums. The actual necessary daily amount of protein according to the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) is only 0.66 grams per kilogram of body weight, given that the protein consumed is well-digestible and of high-quality.9

Based on the DGE’s recommended 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight, a healthy 60 kg woman’s daily protein intake would be 48 grams. Using an average caloric value of 4.1 calories (kcal) for each gram of protein, this corresponds to a daily intake of about 197 calories (kcal) from protein per day. With average energy requirements of about 1800 to 2100 calories (kcal) per day10 (depending on activity levels), this is about 10 % of total food energy (e. g. calories). As we’ll discuss in detail later, several sources recommend a slightly higher daily protein intake of 0.9 grams per kilogram of ideal body weight for exclusively plant-based diets. We’ll use this value moving on.

Athletes have increased protein intake requirements, but also need more calories in total. A higher caloric intake is matched by a sufficiently higher protein intake corresponding to the Protein-Energy Ratio, the percentage of calories from protein in relation to total calories consumed. This is enough as long as the ratio is 10 % or more, even with lesser quality protein sources.11

Do vegans get enough protein?

The answer to the question if an exclusively plant-based diet can satisfy the protein requirements of the body was provided in a publication by American nutrition expert Dr. David Mark Hegsted in 1946.12 He emphasized that that a grain-oriented, entirely vegan diet of sufficient calories can meet protein intake requirements. The report relies on the result of a study including 26 participants on a completely vegan diet which were able to achieve a positive nitrogen balance with a protein intake of 0.5 grams per kilogram of body weight. A positive nitrogen balance is a relevant factor in determining if an individual is getting adequate protein. The scientists Dr. Vernon Young and Dr. Peter Pellett also confirmed the ability to meet protein requirements on a vegan diet in a study published in 1994 on the role of protein in nutrition. This publication also showed that on a well-balanced completely plant-based diet with sufficient caloric intake a shortage of protein is not a concern.13 Additionally, both were already aware that relying on conventional animal experiments with rats to attempt to assess protein quality runs the risk of potentially underestimating the role of plant protein in human diets. Early experiments were usually conducted by feeding rodents different types of protein and observing their growth to draw conclusions about the quality of the protein. However, protein from plants often has less of the amino acids that meet requirements for rats, which are higher than for humans. As a result, feeding trials with rats can underestimate the value of plant protein sources for humans.14 At the conclusion of their paper, the authors provide a concise listing of common myths about protein and determine if the statements are grounded in reality. Inspired by this approach, I’ll also list and address the most common myths related to each topic at the end of each chapter of this book.

A number of studies from Great Britain15, Sweden16, Germany17, Switzerland18, and the USA19 likewise reinforce that vegans typically obtain more than 10 % of their calories from protein, thus satisfying official daily protein intakes if their caloric requirements are met. The ground-breaking position paper of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND), formerly the American Dietetic Association (ADA), first published in 2003, officially acknowledged that an appropriately planned diet can ensure adequate protein at any stage of the life cycle.20 This paper was updated in 2009,21 and again in 2016,22 continuing its endorsement a vegan diet for anyone, any type of athletic activity, at any stage of life. Other health organizations, such as the British Dietetic Association (BDA), are also confident a well-planned vegan diet can supply adequate protein for all life stages.23 The statement of the Dietitians Association of Australia (DAA) on the subject of plant-based diets doesn’t even mention protein deficiency, instead emphasizing the importance of getting enough iron, calcium, vitamin B12, and omega-3 fatty acids.24

The American Heart Association (AHA) also assures us that it’s not necessary for anyone to eat animal products to meet their nutritional needs, and that plant protein provides adequate essential amino acids on a well-rounded diet with enough calories.25

Plant-based protein sources

It’s easy to check and see for yourself if you’re getting enough protein to meet daily requirements. With an online nutrition calculator or calorie tracking app, such as Cronometer (www.cronometer.com) just enter the amounts of your choice of legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seeds. You’ll notice that well before reaching the minimum calorie requirements, your protein intake is already enough. You can source remaining calories from an abundance of healthy fruits and vegetables, which may not be packed with protein, but ultimately round out an adequate, nutritious diet. Protein amounts in processed foods, like tofu vary considerably from one manufacturer to the next. For this reason, it’s important to take a look at the nutritional information on packages for more reliable values. Keep in mind that dried products, such as lentils and pasta, increase significantly in weight when cooked, so pay attention to the difference between uncooked (dry) weights and cooked weights when determining protein amounts. This confusion has often led to online graphics comparing protein amounts in legumes and meat in which black beans appear to contain nearly twice as much protein as beef. In such cases, dried beans have been compared with raw beef, misrepresenting beans, because when they’re cooked beans increase in weight significantly more than meat. We’ve got to remember to compare cooked legumes with cooked meat. Cooked legumes still do provide adequate protein and other nutrients, so we shouldn’t really worry how they compare with animal proteins. Figure 5 shows how dried products such as legumes, pasta, grains, and other foods increase in weight when cooked.

To use the factors from the diagram to determine how much protein is in each food when cooked, you’ll first need to find the protein figures from the nutrition labels on the dried products. Next, using the factors and formulas, calculate how much protein is in the cooked product relative to the amount the dried product contains. For example, red lentils labeled with 24 grams of protein per 100 grams of dry weight are multiplied according to the diagram by a factor of 2.25x to estimate the average cooked weight. 100 grams of dried lentils yields on average 225 grams of cooked lentils, which contains 24 grams of protein. Those 24 grams now correspond to 225 grams of cooked weight, not the original 100 grams of dry weight, as the lentils have increased in weight by absorbing water during cooking.

Figure 5: General guidelines for determining cooked weights of dried foods26

Rounded off, the cooked lentils now contain about 10 grams of protein per 100 grams. The exact amount of weight increase will vary between types of lentils and depends on the duration of soaking and cooking times as well as the amount of water used, and serves as an approximate value. The values shown are averages. For example, depending on soaking and cooking times, the same quinoa can increase in weight by a factor or 2.75x, 3x, or even up to 3.25x, if cooked very soft after being soaked first. We see similar variations with other dried products. If you want to know the amount of the weight gain based on preferred cooking methods more precisely, it’s worth testing in your own kitchen to be able to make better calculations.

Figure 6 displays the amount of protein in several good sources of plant protein. Protein amounts for common dried products like legumes and grains have already been converted to reflect cooked weights. This provides our first decent overview of plant-based foods that are especially suitable for meeting daily protein requirements on a completely vegan diet.

The diagram makes it apparent that many plant foods contain significant amounts of protein. The frontrunners among sources of plant protein, including pumpkin seeds, hemp seeds, peanuts, and so on, supply large amounts of protein, but also contain a lot of fat and calories. For that reason, they shouldn’t be the primary sources of protein on a vegan diet, but do complement other sources excellently. Legumes and grains, as well as products made from them, should be the main plant-based food sources of protein. These do contain somewhat less protein per 100 grams, but have considerably less calories because of their lower fat content, making them comparatively better sources of protein.

Figure 6: Protein content of selected plant-based foods27,28,29

The following example shows how easy it is to meet protein requirements on a vegan diet by complementing legumes and whole grains with nuts and seeds: An individual who weighs 60 kg has scrambled tofu for breakfast with 120 g tofu (15 g protein), 100 g mushrooms (3 g protein), 10 g pumpkin seeds (3.5 g protein), and 2 slices of whole grain bread (5 g protein). For lunch, they cook 180 g lentil pasta (dry weight 80 g, 22 g protein) with 200 g tomato sauce (3 g protein) and 20 g cashews (4 g protein). After a quick calculation, we see they’ve already consumed 55 grams of protein. They’ve already more than completely met their protein requirements in the first half of the day! We could also just as easily propose a protein-rich start to the day with whole wheat bread, hummus (with tahini), and peppers, or oats with soy milk, nuts, ground flaxseeds, and fruit for breakfast. Lunch could be a quick quinoa salad with spinach, peas, and a peanut dressing or lentil soup with brown rice and roasted almonds. Dinner might be a creamy chickpea and vegetable curry with some almond paste and millet on the side, or stir-fried vegetables with tempeh, quinoa, and roasted sunflower seeds. Whatever they decide to eat, as long as their daily meals consist of mostly whole grains and legumes and are complemented by nuts and seeds, their diet is doing an excellent job of supplying protein. Even with the justifiable focus on protein, we shouldn’t neglect to get enough fruit and vegetables, too. Both food groups don’t really provide a lot of protein, but they’re abundant in all kinds of vitamins and phytonutrients and should play an important part in any vegan diet.

Plant-based protein vs. animal protein

In the frequently one-sided discussion about whether animal or plant-based foods are the best source of protein, we tend to lose sight of the fact that we don’t eat food just to get protein. Walnuts, for example, are important not only for their protein, but also because they are rich in omega-3 fatty acids and vitamin E. Similarly, when we talk about tempeh, we should appreciate the fiber, phytonutrients, and broad spectrum of fatty acids they provide in addition to protein. Foods are packages of nutrients, and should always be seen as a package deal. This is why it’s not always helpful to compare types of foods on the primary basis of which contain the most protein. At this point we should look at two different ways of evaluating and ranking protein-rich foods. The first method concentrates on the absolute amount of protein listed with the nutritional information found on the package of the food. If you’re buying unpacked produce, or for some reason the protein content isn’t labeled on the package, you’ll just need to take a look at a nutritional chart available from a number of sources. The other, equally useful method focuses on the amount of protein in relation to the total number of calories in the food. Since animal products don’t contain fiber, their caloric content is usually more densely concentrated than that of plant-based foods. Because daily nutritional requirements are almost always measured in calories, this assessment is particularly meaningful, as is the actual ratio of calories from fat to protein and carbohydrates. Of course, a gram of fat weighs the same as a gram of protein or carbohydrates, but the gram of fat has twice as many calories as either of the other two. Figure 7 uses the example of cooked lentils and cooked eggs to illustrate the difference in protein content with relation to weight and calories.

Figure 7: Protein content of cooked lentils and eggs compared by weight and calories

An egg contains a lot of protein, but considerably more calories from fat than from protein

Figure 7 shows that 100 g cooked eggs (edible portion, not including shells) contain about 12.6 g protein, 10.6 g fat, and just 1.1 g carbohydrates.30 In relation to the amount of protein, fat, and carbohydrates in grams, eggs contain a ratio of 51.9 % protein, 43.6 % fat, 4.5 % carbohydrates, and 0 % fiber. We conclude that eggs are just over a half protein. In looking at the weight of the macronutrients, we see that’s actually the case. Yet, fat provides on average 9.3 calories per gram, which is more than twice as many calories as protein or carbohydrates (each about 4.1 kcal/g). The ratio looks different now relative to the total calories, with protein providing about one third of the calories in eggs. Focusing on the caloric content of eggs, 33.4 % of calories come from protein (51.7 kcal), 63.7 % from fat (98.6 kcal), 2.9 % from carbohydrates, and 0 % (0 kcal) from fiber. From this perspective, eggs do contain a lot of protein, but ultimately most of the calories come from fat, not protein.

100 g of cooked lentils contain 10.4 g protein, 0.7 g fat, 18 g carbohydrates, and 7.6 g of fiber.31 Looking at the amount of secondary nutrients, we see a ratio of 28.3 % protein, 1.9 % fat, 49.1 % carbohydrates, and 20.7 % fiber. Fibers are also carbohydrates, but because the body can only use them for producing a small amount of energy, nutritional tables usually list them as providing 2 kcal instead of 4.1 kcal/g. Looking at the proportional breakdown of the macronutrients in relation to the total number of calories each provide, lentils contain 30.9 % protein (42.6 kcal), 4.7 % fat (6.5 kcal), 53.4 % carbohydrates (73.8 kcal), and 11 % fiber (15.2 kcal). In Figure 7 we see there’s a significant difference in the percentages of protein content of eggs between the two approaches: 51.9 % vs. 33.4 % protein. This is due to the larger amount of calorie-dense fat in the egg yolk compared to the minimal fat content of lentils. Proportionally speaking, lentils consist of nearly a third protein and therefore boast almost the same amount of protein as eggs. The numbers get even closer if we go a step further and calculate how much more lentils we can eat thanks to their rather low caloric density to arrive at the same amount of calories we’d get eating eggs.

Cooked eggs have on average 155 kcal/100 g of edible egg (without shell).32 Freshly cooked red lentils have about 138 kcal/100 g.33 Theoretically, you could eat about 112 g of lentils to get the same number of calories as in eggs (155 kcal), and get 11.6 g protein in the process, which is now just 1 g less than in eggs.

Protein deficiency and calorie deficiency

Protein deficiencies are usually linked to not getting enough calories and are not common on well-balanced plant-based diets. The German Vegan Study (Deutsche Vegan-Studie—DVS) showed however, this isn’t always the case. The vegans participating in the study consumed on average over 10 % of their dietary energy in the form of protein, but around a quarter of the participants weren’t satisfying the recommended daily intake for protein.34 This simply comes down to those subjects not consuming enough calories. In relative terms, they actually were getting enough protein from their food choices, and would’ve met daily protein needs if they’d just eaten enough of these foods to meet their caloric requirements. Put simply, a protein deficiency on a vegan diet usually means a calorie deficiency. Both can be safely avoided by obtaining sufficient calories from a balanced assortment of nutritious plant foods.

The only exceptions to this generalization tend to be a few very restrictive types of vegan diet. These include extremely limiting forms of raw diets which mostly or entirely avoid whole grains and legumes. According to the findings of the Gießner raw food study, both protein and energy were in fact lacking in several of the participants following exclusively raw food diets35 Strict fruitarians, who follow the extremely restrictive guidelines of dietary models like the 80/10/10 diet by Dr. Douglas Graham, run the risk of not getting enough protein and other essential nutrients. 80/10/10 stands for the percentage ratio of the macronutrients carbohydrates, fat, and protein. Although the diet aims for 10 % protein, a number of the diet’s adherents fall short on protein, due to the diet’s abundance of fruits, scarcity of leafy vegetables, nuts, and seeds, and complete absence of whole grains and legumes. Several claims of the 80/10/10 diet, such as “fruits are replete with the nutrients our bodies require, in the proportions that we need them” are simply false, and they misrepresent what a nutritionally adequate plant-based diet entails.36 Even when combined with an abundance of green, leafy vegetables it’s just mathematically challenging to always get enough protein and a few other essential nutrients while following a calorie-sufficient 80/10/10 diet. You could meet the recommended protein intake by just eating a lot of nuts and seeds, but then you’d undoubtedly far exceed the 10 % fat limit the diet imposes.

It’s easy to verify this yourself by arranging a combination of fruits, vegetables, and small amounts of nuts which meet your individual caloric needs and inputting it on www.cronometer.com to determine the intake of protein, amino acids, and other nutrients. Adverse claims such as those made by publications denouncing legumes and grains are not supported by current scientific understandings, as we will see in the upcoming chapters. In the meantime, it’s important to understand that there’s no reason to eliminate either of these healthy and important food groups from your vegan meals. When talking about vegan diets in this book, this does not imply any forms of specialized, highly-restrictive plant-based diets, but rather a balanced, nutritious plant-based diet with abundant whole grains, legumes, fruit, nuts, and seeds.

Optimizing protein intake

Although it’s mathematically improbable to fall short of minimum protein needs when following a nutritious vegan diet which gets enough calories, the goal shouldn’t be just an adequate protein intake, but rather an optimal protein intake. It’s actually not difficult at all to achieve entirely plant-based and just requires observing a few things. In addition to sticking to calorie requirements, another major obstacle for vegans striving to optimize their protein intake is not consuming enough legumes. Legumes are nutritionally valuable in many regards, but for now let’s concentrate on the importance of the relatively high amounts of the essential amino acid lysine.37