Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Children's Books

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

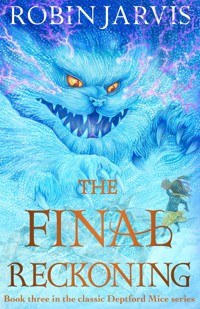

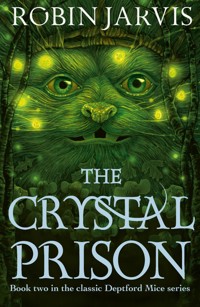

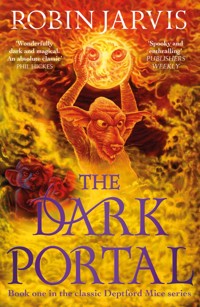

- Serie: The Deptford Mice

- Sprache: Englisch

The Deptford Mice live a comfortable life in the skirting boards of an abandoned London house, with no humans or cats to disturb them. But something is lurking deep beneath the city. Something that threatens to destroy their cosy existence for good. In the dank sewers under the house lives a mysterious being, worshipped by a horde of bloodthirsty rats who cower in its presence...When a mouse called Albert Brown unwisely ventures down into the sewers one day, he uncovers a terrifying plot to awaken an ancient evil. Soon Albert's family and friends find themselves in a desperate struggle for their lives. Summoning all their courage, they must confront treacherous enemies and foul sorcery in a battle to save London and the world from eternal darkness.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 346

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for The Deptford Mice series

‘The perfect stories for dark, cosy evenings. A once-read-never-forgotten series’

Phil Hickes, author of The Haunting of Aveline Jones

‘A grand-scale epic… Filled with high drama, suspense, and some genuine terror’

Lloyd Alexander, author of The Chronicles of Prydain

‘Spooky and enthralling animal fantasy just right for Redwall fans… [Jarvis] provides counterpoint to the heart-racing adventure with scenes of haunting beauty’

Publishers Weekly, Starred Review

‘Robin Jarvis joins the ranks of Kenneth Grahame, Richard Adams and Walter Wangerin in the creation of wonderfully anthropomorphic animals’

Madeleine de L’Engle, author of A Wrinkle in Time

‘In The Dark Portal Robin Jarvis delights the reader with not just one, but three unforgettable animal societies… He offers a strikingly original, totally absorbing fantasy world’

Philip Glassman, founder of the Books of Wonder bookstore

3

5For my parents6

Contents

The Mice

albert brown

A loving father and devoted husband. Albert is a commonsensical mouse, not usually given to rash actions.

arthur brown

Stocky and light-hearted, Arthur likes a scrap but always comes off worse.

audrey brown

Tends to dream. She likes to look her best and wears lace and ribbons. Audrey cannot hold her tongue in an argument, and often says more than she should.

10gwen brown

The gentle wife of Albert and caring mother of Arthur and Audrey. Her love for her family binds it together and keeps it strong.

arabel chitter

A silly old nosey nibbler, who gets on the nerves of everyone in the Skirtings.

oswald chitter

Arabel’s son, an albino runt. Oswald is overprotected by his mother and not allowed to join in some of the rougher games.

piccadilly

A cheeky young mouse from the city, Piccadilly has no parents and is very independent.

11thomas triton

A retired midshipmouse. Thomas is a heroic old salt – he does not suffer fools gladly.

william scuttle or ‘twit’

A fieldmouse visiting Arabel Chitter, his mother’s sister. Twit is an innocent and does not have a bad word to say about anyone.

eldritch and orfeo

Brothers, who as bats can see far into the future. Bat advice is a very dangerous thing to seek, for they tell you only fragments of what they know.

the green mouse

A mysterious figure in mouse mythology. He is the spirit of spring and of new life.

The Rats

madame akkikuyu

A fortune-telling ratwitch. She wanders around selling potions and charms to gullible customers.

finn

A sly old worker – one of his ears is missing, but he doesn’t miss much.

fletch

A dirty old rat with bad breath and spots on his nose.

13one-eyed jake

A popular rat who is threatening to oust Morgan from office.

jupiter

The great dark God of the Sewers. He lives in the dark portal and possesses awesome powers. All fear him.

leering macky

A rat with a terrible squint. He and Vinegar Pete are old cronies.

morgan

The Cornish piebald rat who is Jupiter’s lieutenant. Morgan trusts no one and does all Jupiter’s dirty work.

14skinner

A rat with a mouse-peeler strapped on to his stump of an arm.

smiler

A strong giant of a rat who works in the mine.

vinegar pete

This rat never smiles. His face is always sullen and he and Leering Macky mutter to themselves.

15

The Grille

When a mouse is born, they have to fight to survive. There are many enemies – owls, foxes and of course, cats; but mice suffer far more at our hands. I have heard of a whole family of kind, gentle mice, wiped out by eating poison – four generations gone and only the baby left because it was too small to eat solids.

Mice are all descended from rural families, and they remember their ancient traditions wherever they live. They honour the green spirits of the land, as humans once did and every spring they hold a celebration for 18the awakening year, calling to the Green Mouse to ripen the wheat and see them safe.

In a borough of London called Deptford there lived a community of mice. An old empty house was their home and in it they fashioned a comfortable life for themselves. People never disturbed them with traps, and because all the windows were boarded up, they never even saw a cat.

So they dwelt there quite happily. In the winter they would visit the building next to theirs where a blind old lady lived and eat from her pantry. She never minded; her nephews always brought cakes and chocolates so there was too much for her alone. The mice never took more than they needed anyway. There was also fruit and berries on the trees and brambles that hugged the house and some of the younger mice would venture outside to pick them. The only blight on their carefree existence was the sewers – or rather the rats that lived in them. Cut-throats and pirates the lot of them. Thin and ugly, a rat would smack his lips at the thought of mouse for dinner. He would kill, peel and, if he was a fussy eater, roast it. Not that the rats ever came out of the sewers – they had enough muck and slime down there to keep them happy. No, what worried the mice was the Grille.

This fine example of Victorian ironwork was in the cellar of the empty house. Beyond it lay a passage that led straight to the sewers. It nagged on the mind of every mouse. The Grille, with its scrolling leaf pattern of cast iron, was all that divided them from the bitter 19cruelty of the ratfolk and their dark gods. All the mice in the Skirtings knew of the Grille. It was the gateway to the underworld, the barrier between life and death. Only whispering voices could discuss the sewers, in case strange forces were awoken by their mention out loud. The mice knew that deep below ground, beyond the Grille, was a power, which even the rats feared. No one dared to name it in the Skirtings – it was enough to still any conversation and bring a sudden, sober halt to merrymaking.

And yet the Grille seemed to draw mice to it. Evil enchantments were woven about it and, in one corner, there was a rusted hole, which a mouse could squeeze through, if he was foolish enough to do so.

One such mouse was Albert Brown. He could never afterwards understand what had compelled him to do such a crazy thing, but through the Grille he had gone.

Albert had a wife called Gwen and two children, Arthur and Audrey, so you see he had everything to live for. He was happy and his family was content. There was just no reason and he kicked himself for it. With a shudder he remembered the warnings he had given his own children: ‘Beware of the Grille!’ He had never been brave or overly curious, so why did the Grille call to him that spring morning, and what was the urge to explore that gripped him so?20

1

The Altar of Jupiter

The sewers were dark, oppressive and worst of all, smelly: Albert had gone quite a way before he shook himself and, with a horrified jolt, suddenly became aware of his surroundings. Quickly he stifled the yell that gurgled up from his stomach and raced out of his mouth. Then he sat down and took in the situation.

He was on a narrow ledge, in a wide, high tunnel. Below him ran the dark sewer water. Albert cursed the madness that had gripped him and sent him running into danger.

22‘Yet here I am,’ he thought ruefully and wondered how far he had come. But he was unable even to recall how long since he had left the Skirtings. Alone, in the darkness, Albert sat on the brick ledge trying to quell the panic that was bubbling up inside him. He pressed his paws into his stomach and breathed as deeply as he could.

‘Got to get out! Got to get back!’ he said, but his voice came out all choked and squeaky and echoed eerily around the tunnel. This frightened him more than 23anything: the ferocious rats lived down here. Around the next corner a band of them could be waiting for him, listening to his funny cries of alarm and laughing at his panic. They might have knives and sticks. What if they were already appointing one of them to be the mouse peeler? What if…?

Albert breathed deeply again and wiped his forehead. The only thing to do was to remain calm: if he succumbed to fright then he would stay rooted to the spot and the rats would surely find him. He stood up and set his jaw in determination. ‘If I use my wits, all I have to do is retrace my footsteps and return to the Grille,’ he told himself.

It was many hours later when Albert sat down on yet another ledge and wept. All this time he had tried to find his way out, but he had been unable to recognize anything that could tell him he was on the right track. What hope had he of returning to his family? He groaned and wondered what time of day it was. Perhaps it was another day altogether? Then he remembered and hoped that it was not. The Great Spring Celebration was today, and he would miss it. He would miss the games, the dancing and the presentations. Albert hung his head. His own children, Arthur and Audrey, were to be presented this year; they had come of age and would receive their mousebrasses. Today was the most special day in their lives and he would miss it. Albert wept again.

In his sorrow he put a paw up to his own mousebrass hanging from a thread around his neck.

24It was a small circle of brass that fitted in the palm of his paw. In the centre of the golden, shining charm, three mouse tails met. It was a sign of life and an emblem of his family. Albert took new hope from tracing the design with his fingers – it reminded him that there were brighter places than this dark sewer and he resolved to continue searching until he found home – or death.

He resumed walking along the ledge, his pink feet scarcely making a sound. All too aware of the dangers, he made his way carefully, keeping close to the wall. Presently he heard a faint pit-a-pat from around the next corner. Something was approaching.

Albert turned quickly and looked for a place to hide, but there was nowhere and no escape. His heart beating hard, he pressed himself against the bricks and tried to merge into the shadows. Albert held his breath and waited apprehensively.

From around the corner came a shadow – it sprawled menacingly over the ledge and flew into the darkness of the tunnel. When the shadow’s owner finally emerged, Albert gasped in spite of himself. It was a mouse!

All his fears and worries melted, and he was flooded with such overwhelming relief that he hugged the stranger tightly.

‘Gerroff!’ protested the mouse, struggling to get free.

Albert stood back but continued to shake the other’s paw with gleeful vigour.

25‘Oh you’ve no idea how glad I am to see another mouse,’ Albert said.

The stranger was just as thankful. ‘Me too, though you gave me an ’orrid fright pouncing on me like that. Piccadilly’s the name. Wotcha, geezer!’ He took his paw from Albert’s and pushed back his fringe. ‘Who’re you then?’

‘Albert, Albert Brown. How did you get down here, in this horrible place?’

Piccadilly told him his story while Albert looked him over. He was young, a little older than Albert’s children because he already had his mousebrass. He was also grey, which was unusual in the Skirtings, and he had a cheeky way of speaking. Albert put that down to Piccadilly’s lack of parents: who he learnt had been killed by an Underground train some time ago.

Piccadilly had been involved in one of the food-foraging parties in the city when he had lost his comrades and, like Albert, strayed into the sewers.

‘And here I am,’ he concluded. ‘Mind you, where that is I’ve no flippin’ clue.’

Albert sighed. ‘Neither have I, unfortunately. We could be under Greenwich or Lewisham, or anywhere really…’ His voice trailed off and he looked thoughtful.

‘Anythin’ wrong, Alby? You got a face like a bottle of chunky milk.’

‘There’s plenty wrong, and less of that sauce, Dilly-o!’ Albert scratched an ear and looked sternly at the young mouse. ‘Apart from the fact that I shall miss my children’s mousebrass presentations, as yet I’ve seen neither hide nor 26whisker of any rats down here, so it’s only a matter of time before we run smack bang into them.’

Piccadilly laughed. ‘Rats! Slime-stuffers? Are you scared of them gutless snot-gobblers?’ He paused to hold his sides. ‘Why, I’ll handle them for you, grandpa. A few ripe bits of well-chosen chat from me, will get ’em runnin’ and wailin’ for their ugly mums.’

Albert shook his head. ‘Around here the rats are different. They’re not the cringing bacon rind-chewers that you have in the city. No, these are far, far worse. They have cruel yellow eyes and are driven by a burning hatred of all other creatures.’

‘I’ll drive ’em!’ Piccadilly scoffed. ‘Ain’t nowt different, Alby, rats is rats wherever!’

Albert narrowed his eyes and lowered his voice. ‘Jupiter,’ he whispered in dread. ‘They have him.’

The young mouse opened his mouth, but no cheek came out. ‘Crikey!’ he uttered. ‘In the city we’ve heard rumours of Jupiter, the awful God of the Rats, Lord of the Rotting Darkness… is he here, for real?’

‘Yes, and somewhere close,’ Albert replied unhappily.

‘Are the myths about him true then? Has he two great ugly heads, one with red eyes and the other with yellow?’

‘No mouse has seen him, but I don’t think the rats have either – I’ve heard he lives in a deep hole and doesn’t come out. I’ll wager Morgan has seen him though.’

‘Who’s he?’

‘Morgan is his chief henchrat, and slyer than a sack of lies. He does most of Jupiter’s dirty work.’

27Piccadilly looked around, nervously. The gloom seemed to press in on him now. ‘So the rats here aren’t frightened belly crawlers then?’

‘Savage and cruel,’ came the solemn reply. ‘If we’re caught, they’ll eat us. If we’re lucky, they’ll kill us first. So we really should get out of this place, just as soon as we can.’

‘We’d best find your gaff double quick then.’

They set off together, searching the tunnels, balancing along pipes, bridging the gurgling water and exploring deep into pitch-dark arches. Paw in paw, the two mice found comfort in each other’s company; but both were mortally afraid. All they could hear were steady drips and every so often a ‘sploosh!’ echoed weirdly through the passageways. Sometimes they had to turn back when the smells got too bad and made their whiskers itch. Then a tunnel would end abruptly, and they were forced to retrace their steps to the last turning.

The sewer ledges were treacherous. The shadows hid every kind of trap: holes, stones and slimy moss. Albert and Piccadilly made slow and wary progress.

Way above them, in the great wide world, the new moon of May climbed the night sky and only the brightest stars could be seen above the orange glare of the city lights.

‘Another dead end!’ muttered Albert in exasperation.

‘Do you think we’ll ever get out?’ Piccadilly asked quietly.

The older mouse could see, even in the murky darkness, that Piccadilly’s eyes were wet, and he was sniffling. Albert squeezed his paw gently.

28‘Let’s rest a little while,’ he said, sitting down. ‘Of course we’ll get out. Why, I’ve known mice in much worse pickles than this, and they’ve won through, tail and all. Take Twit – now there’s a fine example!’

‘Who’s Twit?’.

‘A young friend of my children – must be your age though – got his brass you see: an ear of wheat against a sickle moon.’

‘He’s one of the country folk then?’ said Piccadilly, brightening a little. Talk of the outside and the chance of a story cheered his spirits. Albert was quite clever and tactful.

‘Yes, Twit’s a fieldmouse, and the smallest fellow to wear the brass that I’ve ever seen. In the dead of winter, he came to the Skirtings to visit his cousin.’

‘In winter, with the snow an’ all?’

‘Snow and all,’ said Albert. ‘He had a terrible journey and many unexpected happenings on the way.’ He paused for effect.

‘Foxes, owls and stoats he met, and more besides. “Suave is Mr Fox”, Twit told us. “You have to be careful of him” – Old Brush Buttocks he calls him.’

Piccadilly laughed. ‘Twit’s an odd name,’ he mused.

‘Comes from having no cheese upstairs, if you under stand me.’

‘And hasn’t he? Is he a bit dim?’

‘That’s a tricky one: first sight yes, but then no.’ Albert sucked his teeth for a while. ‘If I had an opinion and the right to tell it, it would be that Twit is an 29innocent. He’s forever thinking of the good: he’s not dim or simple – no – or else he’d never have made it from his field. No, I think it’s something which other animals sense and they leave him alone. In the nicest possible way, Twit is… green, as green as a summer field, as green as…’

‘The Green Mouse,’ Piccadilly said.

‘Exactly! Now that’s a better thing to think of: The Green Mouse in His coat of leaves and fruit.’

Piccadilly shook his head. ‘I stopped believing in Him a long time back,’ he said. ‘But I’d like to meet this Twit, if we ever get out of here, that is.’

‘We will, and you can meet Oswald as well. They’re a funny pair.’

‘Oswald?’

‘Twit’s cousin.’

‘Tell me about him.’

‘Another time,’ said Albert, rising to his feet. They had lingered long enough. They were too vulnerable here and had to get moving.

‘We’d better get a scurry on – and let’s make this the last stretch, eh?’ His fears were mounting, but he did not want the younger mouse to sense it. He was beginning to feel very paternal towards this brash orphan from the city.

They started off again. Piccadilly ran his paw along the bricks. ‘I suppose it’s all a big adventure really,’ he told himself. ‘Ought to make the most of it, then if I ever get back to the city, I can tell the…’ He paused sharply.

30‘Alby! I’ve found something. Come see, there’s a small opening in the wall.’

Albert peered into the hole that Piccadilly had found. The air was still and strangely lacking in all smell. Mr Brown twitched his whiskers and tried to catch a scent that would give them a clue to what lay beyond. There was nothing.

The hole was darker than anywhere they had been so far.

‘Goes in a fair distance,’ Albert guessed shrewdly. ‘We’ll be blind as moles in there. Should we risk it and see where it comes out?’

‘We can always pop back if it’s another dead end,’ Piccadilly answered.

The opening was just wide enough for them to squeeze through. Once inside, they found they were able to stand quite comfortably, although the inky dark was unnerving and they often stumbled over unseen obstacles.

Strange thoughts came to Albert as he led the way, holding tightly to Piccadilly’s paw. He felt they were crossing an abyss, descending into a deep gulf of consuming shadow. He was unable to make out his own nose, and in the raven murk, his imagination conjured images before his straining eyes: visions of his wife Gwen, and Arthur and Audrey, forever beckoning yet always distant. Albert despaired and nursed his sorrow, in silence.

Following blindly, Piccadilly clung to Albert’s paw. He had never experienced a darkness like this before, not even in the tunnels of the Underground in the 31city. This was a total dumbfounding of the senses; he could see nothing, smell nothing, and even sound was muffled by the suffocating night. He tried not to think of the sense of taste, as he had not eaten for a very long time. The only thing left to him was touch and he was kept painfully aware of this every time his toes banged against stones and were grazed by rough brickwork. The dark seemed to have become an enemy in its own right, a being which had swallowed him. Even now he felt he could be staggering down its throat.

Albert’s paw was the only real thing. The floor and the passage walls were confused – vague contacts that made him giddy.

They had not spoken for a long time and Piccadilly wondered whether Albert had been secretly replaced by some monster that was leading him to an unknown horror. This thought grew and turned into a panic. The panic seized him fully and became icy terror. He began to struggle from the paw which now seemed to be an iron claw dragging him to his doom.

Then he was free of it and alone. All alone.

The initial relief rapidly turned to fright as the immeasurable unknown engulfed him, isolating him from all that was real. He could not contain his anxiety much longer. He closed his eyes but found there the same darkness, as if it had seeped into his mind.

‘Piccadilly?’ Albert’s gentle voice floated out of nowhere and at once the fear fell away. ‘Where’s your paw? Come on, lad, I think I see a hint of light ahead.’

32It was a faint orange glow, where the passage came to an end, and they made for it gladly.

‘Trust in the Green Mouse, Dilly-O. I knew we’d be all right.’

Cautiously, they peered out, blinking while their eyes adjusted. In front of them was a large chamber with numerous openings leading off into other tunnels. Along a ledge nearby, two stout candles were burning steadily.

Between them was a figure, crouched in an attitude of subservient grovelling. It was a rat.

He was a large, ugly, piebald creature with a ring through one ear and a permanent sneer on his sharp, chiselled face. He had small, beady eyes that flicked constantly from side to side.

The two mice pressed themselves further back inside the passage, their hearts pounding. The rat had a stump of a tail with a smelly old rag tied around the end. He swung it behind him with an ungainly, unbalanced motion. It was Morgan – the Cornish rat, Jupiter’s lieutenant.

Although Albert was dreadfully afraid, he was anxious to see what the rat was humbling himself before. Peering up, beyond the flickering candle flames, Albert could see an arched portal in the brick. There, blazing in the shadows, were two fiery red eyes, impossibly large and equally evil. Albert clamped a paw to his mouth, as the awful reality dawned. He and Piccadilly had blundered into the very heart of the rat empire. They were within whispering distance of the altar of Jupiter.

33Albert hoped no one would catch scent of Piccadilly and himself, yet he dared not move for fear of making a noise. He remembered that rats loved to peel mice and he shivered. Piccadilly did not need to question the identity of those burning eyes: the powerful malevolence that beat out from them was enough to tell him that this was the legendary God of the Rats.

Morgan raised his head and spoke into the shadows.

Albert cupped an ear to catch the words, but it was difficult. Jupiter’s answering voice was soft and menacing; it both soothed and repelled.

‘And why has the digging been delayed?’ he demanded from the dark.

Morgan bowed again. ‘Lord!’ he whimpered. ‘You know what the lads are like, “What for we doin’ this?” they do say, an’ “Gimme a mouse!”. Fact is – they’m bored, an’ right cheesed off. They want action – an’ now.’ The rat looked up and squinted in the glare of those blazing eyes. ‘One quickie like – grab’n’dash – with a bit of skirmishin’ in the middle.’ He licked his long yellow teeth.

‘My subjects must do all I ask of them,’ Jupiter said flatly. ‘Do they not love me?’

‘Oh in worshipful adoration, Your Lovely Darkness, more than they love themselves.’

‘Nevertheless, I have asked for one simple task to be undertaken and all I hear is incessant whining. I fear they have little affection for me.’ The voice rose and a sour tinge crept into it.

‘Never, Your Magnificence! Why else would they bring you their tributes: the Cheddar biscuits – nearly 34a whole half-packet last week; and that packet of rancid bacon! Fair tore their hearts to part with it, but they did. All for your love, Great One! For your greater glory, oh Voice in the Deep.’

Morgan wrung his claws together for the finishing touch and hung his head so low that his snout touched the floor, for extra emphasis.

‘Love!’ Jupiter spat with scorn. ‘They do these things from fear.’ The soft voice snapped, resounding around the large chamber. The eyes became slits but lost none of their fire.

‘I am Jupiter! I am the sinister threat which haunts their waking hours, I invade their vilest dreams and bring despair! I am the essence of night, the terror around the corner, the echo behind! They fear me!’

Morgan threw himself down. The candles flared and towering flames scorched the chamber’s arched ceiling.

Piccadilly shrank against the tunnel wall. This was their chance to escape but, fascinated by the scene before them, he and Albert remained frozen to the spot.

Jupiter continued. ‘You do well to prostrate yourself before me,’ he told Morgan. ‘Perhaps you forget my power and hope to beguile and cheat me with the honeyed words that ooze from your deceitful tongue. Remember your place as my servant!’ The soaring candle flames spluttered and turned an infernal red, so that Morgan appeared to be bathed in blood.

‘Oh Master, spare me!’ he squealed, burying his snout in his grimy claws. ‘They conspire and grumble, and I am caught in between. What can I do?’

35The candle flames dwindled and returned to their normal colour.

‘Send two or three of the troublemakers to me. They shall serve me here in the void, on this side of the candles. Tell the other conspirators that I hear their grumblings – my mind stands beside each one of my subjects.’

Morgan rose and waited for permission to leave.

Jupiter spoke again.

‘Better yet, bring them all before me. A demonstration of my unease should quell their mutinous hearts. I will give them the inspiration they crave for their work. Leave me.’

The rat bowed and scurried into one of the openings that led from the altar chamber. Above the candles, the two eyes retreated into the deep recess and disappeared. The voice, however, could still be heard faintly as Jupiter talked to himself and went over his plans.

Piccadilly tugged Albert’s elbow. ‘Let’s go now,’ he hissed, ‘while we can.’ But Albert was still looking at the portal, trying to pierce the shadows.

‘What’s he up to?’ he murmured softly.

‘I don’t care and you shouldn’t neither,’ whispered Piccadilly. ‘It’s rat stuff – nothing to do with us – some mucky scheme or other – sewer business.’

‘No, lad,’ said Albert, taking a step forward. ‘There’s some terrible evil here and it will affect us all – rats, mice and the big world outside.’ He looked at the young mouse yet did not see him, for his thoughts were far away. He felt an awful doom creeping closer which he 36knew he would have to bear. He turned quickly. ‘I must hear him. You stay here, safe.’

Piccadilly was horrified. The older mouse stole out into the altar chamber and passed the nearest candle until he was directly beneath the dark portal, eavesdropping on the unholy designs of Jupiter.

Piccadilly signalled frantically for Albert to hurry back. Was this mouse cracked? Any minute now a whole army of rats would come pouring into that altar chamber. He watched, helpless, as the expression on Mr Brown’s face switched from disbelief to shock. Whatever Jupiter was plotting, it was clearly horrific. Piccadilly couldn’t begin to guess what it could be and he spun around, staring back into the pitch-dark passageway. They had to run, right now. Determined to drag Albert away if he had to, the city mouse turned back to him.

A strangled squeak of fright sprang from his lips at what he saw. Morgan had returned! Piccadilly tried to yell a warning, but it was too late. Albert felt a terrible pain in his shoulders as they were seized in sharp claws.

Morgan had him and would not let go.

‘Ho, my Lord!’ cried the rat. ‘See what I, Morgan, have found – a spy!’

Piccadilly saw Albert swinging by his shoulders, where Morgan gripped him tightly.

‘Alby!’ he shouted, running from the tunnel.

37‘Another spy!’ Morgan snarled.

Albert wriggled in the rat’s clutches as hundreds more rushed into the chamber. He had no hope of escape. Morgan’s hot, foul breath was on his neck.

‘Piccadilly!’ he shouted. ‘Don’t even try. Run as fast as you can.’ Albert twisted and tore at the mousebrass around his neck. ‘For Gwennie!’ he cried and threw the charm to the stricken young mouse.

‘Don’t dither, lad!’ he yelled, then turned his attention to Morgan. ‘I bet you don’t know what His Nibs has got in store for you! You’re all for the chop!’

Hesitating, Piccadilly clung to the mousebrass. His heart was hammering in his chest and his feet were like dead weights.

The teeming force of rats rushed towards him.

‘Run!’ Albert shouted.

Piccadilly ran.

‘Don’t look back, Dilly-O. Tell Gwennie I love her!’

Jupiter’s voice suddenly boomed in the confusion. ‘Catch that grey mouse and bring him to me!’

Cries and whoops came from the rats enjoying the chase. ‘Now,’ Jupiter turned his sinister attention to Morgan, ‘deliver your spy – I shall peel him myself.’

Pelting blindly through the dark passage, Piccadilly heard, above the uproar of the pursuing enemies, Albert cry out once, then no more.

Sobbing as he fled, Piccadilly clenched the brass tightly.

2

Audrey

Audrey Brown ate a meagre breakfast; her appetite was small today. Idly she nibbled on a cracker and thought about the day ahead. It was to be a busy day in the Skirtings. The preparations for the Great Spring Festival were already being made. With her head resting on one paw, she sighed. Her brother, Arthur, had gulped down two helpings and hurried away to join in the making of the decorations. Audrey was not in the mood. Where was her father?

39It had been a whole day and night since Albert had disappeared – no one had seen him slip through the grating, so nobody knew where to start looking.

That morning, Gwen had woken the children as usual and tried to put a brave face on things. When Albert was mentioned, she would pause and explain that he was probably on a foraging jaunt and would bring them a wonderful present each. But Audrey had heard her mother weeping in the night: her heavy sobs had kept her awake and now she was tired and miserable.

‘Come on, Audrey,’ her mother said. ‘A big day for you, you must eat.’ Gwen Brown’s fur was a rich chestnut and her hair a curly auburn. Today, however, the usually bright hazel eyes seemed dim – her face looked worn and her shoulders seemed to droop.

‘I’m not hungry, Mother,’ Audrey said and pushed the food away. ‘When will Father come back?’

Gwen sat down next to her daughter and cradled her head in her arms. ‘He’s never been away this long,’ she admitted. ‘Perhaps you and I ought to prepare ourselves for grim news – or none at all.’ She stroked Audrey’s hair and held her tightly.

‘Today I get my brass.’ Audrey looked into her mother’s eyes. ‘I’ll be a grown mouse.’ She paused and fingered the brass that hung around Gwen’s neck. It was the respectable sign of the house mouse – a picture of cheese formed in the yellow metal. ‘Mother, do you know what my sign will be?’

40‘No, my love, no one knows – not even the Mouse in the Green who gives it to you. It is your destiny. Whatever you receive, it will be right for you.’

‘Then I hope it isn’t like yours,’ Audrey remarked. ‘I don’t want to settle down and be a house mouse forever.’

‘Well, that’s just what you are, my love,’ said Gwen. ‘Now go and help Arthur and the others decorate the hall while I clear away.’

Audrey left the table and wandered into her and Arthur’s room. Sitting on her bed, she took a pink ribbon from around one of the corner posts and tied it in her hair so that the top of her head looked as if it was sprouting.

She had delicate features – almost elfin. If you could imagine a fairy mouse that would be Audrey, although she would not have thanked you for remarking upon it. Her eyes were large and beautiful; her nose was long, and tapered into a small mouth fringed by long whiskers which she was careful to keep free of crumbs – unlike her brother, who always seemed so messy.

Audrey missed her father terribly: she was closer to him than to her brother.

‘Why aren’t you here?’ she cried violently. She felt angry at him for being away. It was a new feeling, and she was ashamed of it. But where was he? She had looked forward to this, her big day, for so long – but now, without her father, it meant nothing.

All the mice were in the hall outside the Skirtings, decorating busily. From the garden they had brought in bunches of hawthorn blossom and leafy branches – ‘White 41for the Lady and green for the land spirits,’ they cried as they weaved them into garlands. In one corner were the Chambers of Summer and Winter. Each year these were cleaned and dusted and decorated for the mousebrass ceremony. Today those with brasses were working in them, but no youngsters were allowed in.

Two elderly sisters were sewing brightly coloured favours on to the leafy effigies of the Oaken Boy and the Hawthorn Girl. Three stout, sweating husbands had heaved the maypole into the centre of the hall, and already ribbons had been attached to the top of it for the dancing.

Into the chambers strode Master Oldnose carrying a strange straw framework – he was quickly followed by Twit, greatly excited and struggling with a large bundle of leaves and blossom.

Arthur was having a grand time. He was in the middle of it all, hanging up boughs of flowering hawthorn. The scent of the blossom had always excited him, for its heady perfume signalled the end of the bleak months and heralded the beginning of summer.

Oswald Chitter was trying to help him but mostly he was just getting in the way.

‘Could you pass me that pin please, Oswald? Ooch!’ Arthur sucked a sore finger and the row of branches which he had just put up fell down.

‘Oh dear, I’m sorry.’

‘Never mind, Oswald,’ Arthur sighed.

42Oswald was an albino runt – which meant that there was no colour in him at all, except for his eyes which were pink. It also meant he was so weak that he often found it difficult to join in some of the rougher games. He was, however, very tall – perhaps too tall for a mouse. He was painfully conscious of this and was apt to stoop – much to his mother’s annoyance.

‘What sort of brass do you think you’ll get, Arthur?’ he asked.

‘I don’t know, probably nothing too exciting.’

‘You never know what the Green Mouse has in store,’ Oswald said eagerly. ‘I can’t wait for my turn and it’s still a whole year away.’

‘I don’t know about the Green Mouse,’ Arthur replied, ‘but I saw old Oldnose go in there with a bag of clinky things before.’

‘Ah, but that’s just him,’ the other protested. ‘He’s only standing in for the Green Mouse.’

‘He does make the brasses though.’

‘Does not!’

‘Oh yes he does! I’ve seen him in his workroom, hammering and polishing them.’

‘Maybe, but he doesn’t know who gets what! It’s just lucky dip and it always works; they always match the right mouse, so there must be something in it.’

Arthur finished pinning up the hawthorn. ‘Come on,’ he said. ‘Let’s try and find Twit.’

Oswald shook his head. ‘Cousin Twit went in with Master Oldnose – but here’s your mother and Audrey.’

‘Uh-oh,’ warned Arthur, ‘I spy your mother advancing.’

43Mrs Chitter had seen Gwen Brown arrive and made a beeline for her.

‘My dear,’ she breathed. ‘How you must be grieving.’

Audrey frowned. She did not like Mrs Chitter at the best of times.

‘Grieving for what?’ she asked stubbornly.

Oswald’s mother blundered on. ‘Why, your darling father of course – absent now for so long.’ She held out her paw to console Gwen.

Audrey looked at her mother. Her eyes were moist again. What was this silly busybody trying to do?

‘I’m sorry, Mrs Chitter, but Father has not been away for that long really, so there is no need for anyone to mourn – I’m certainly not going to,’ said Audrey fiercely.

‘As you say, dear, you know your own heart, I’m sure.’ Mrs Chitter twitched her whiskers, embarrassed for the moment, then Arthur and Oswald joined them. ‘Ah, boys, I was just saying—’

‘Oh, Mother,’ Oswald interrupted, ‘have you told Mrs Brown what you heard last night?’

Mrs Chitter brightened – a new field of tittle-tattle had been opened for her. ‘Why no! Gwen, you can’t have heard, can you? That travelling fortune-teller is back – you know that awful ratwitch with the shawl who visited last year.’

Arthur pulled Audrey away. ‘Good,’ he said. ‘She’ll gabble on about Madame Akkikuyu for ages – it might take Mother’s mind off things.’

‘She’s an insensitive, stupid nibbler!’ fumed Audrey. ‘Just listen to her twittering. How Mother stands it I 44can’t fathom. If it was me I’d shove her down a hole and jump on her silvery head. It’s all right – she can’t hear me. Just wait till Father gets back!’

Arthur looked at his sister. ‘Audrey, he’s been gone too long. I love him too, but he isn’t here, is he? Today of all days, he would be. You know he wouldn’t miss this for the world.’

‘He’ll be here,’ she said, ‘I know he will.’

Then everything was ready; the garlands were all in place, the maypole erected, and the Chambers of Summer and Winter were pronounced complete. Twit had organized a small trio of musicians with himself on the reed pipe, Algy Coltfoot on the whisker fiddle and Tom Cockle playing bark drum. Together they struck up a merry tune and, from out of one of the chambers, strode Master Oldnose. Normally he was tutor to the young ones but today he was the Mouse in the Green. He was inside a straw framework which he had covered in leaves and blossom, and here and there little bells had been hung, which tinkled as he danced. Acting as the Green Mouse, he masqueraded among the gathered mice and chased the littlest. Everyone clapped and sang. The celebrations had begun.

Gwen Brown was pulled into a corner by Oswald’s mother. ‘Well, she is gifted, you know,’ she continued. ‘She has a crystal in which she can see things, and she sells love philtres and all sorts of potions and medicines. Normally I would be the last mouse to go within smelling distance of a rat, 45but she isn’t one of the sewer kind, you know, she’s not from around here and those rats are different, aren’t they?

‘Anyway,’ she continued, ‘maybe you should consider going to see Madame Akkikuyu yourself, Gwen. Just think, she could tell you where your Albert has got to.’