Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

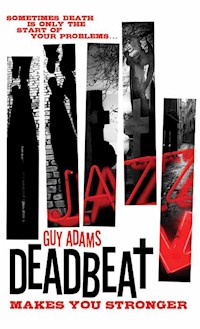

Max and Tom are old, old friends, who used to be actors. Tom now owns a jazz club called Deadbeat which, as well as being their source of income, is also something of an in-joke. In a dark suburban churchyard one night they see a group of men loading a coffin into the back of a van. But, why would you be taking a full coffin away from a graveyard and, more importantly, why is the occupant still breathing? Tom and Max are on the case. God help us...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 357

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by Guy Adams and available from Titan Books

Sherlock Holmes: The Breath of God

Sherlock Holmes: The Army of Dr Moreau

Coming soon

Deadbeat: Dogs of Waugh

MAKES YOU STRONGER

GUY ADAMS

TITANBOOKS

Deadbeat: Makes You Stronger

Print edition ISBN: 9781781162514

E-book edition ISBN: 9781781162521

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: June 2013

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Guy Adams asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Copyright © 2013 by Guy Adams. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at [email protected] or write to us at Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website:

www.titanbooks.com

Contents

Part One

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Part Two

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Part Three

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Part Four

Chapter 12

Part Five

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Excerpt Deadbeat: Dogs of Waugh

PART ONE

1

MAX

1.

There comes a time in everyone’s life when you become aware of a very real and urgent need to look at what you’ve become. That moment when you see yourself with agonising clarity and realise it might be time to make some changes.

Speaking personally, that moment had arrived. Typically, the timing wasn’t good. Hanging from a church bell-tower by my fingers, there seemed little I could do to act on it. I could open up to one of the many pigeons that shared the ledge, staring at me in their peculiar dead-eyed manner. Their counselling skills were no doubt limited, but preferable to the only other option. Call me churlish, but I wasn’t inclined to discuss matters with the bastard that threw me out here in the first place. Childish, perhaps, but he was in my bad books and I was determined to give him the silent treatment.

My left hand slipped in a slick spray of pigeon shit, and I gripped at the iron railing even tighter with my right. That was the pigeons off my Christmas card list as well.

Hanging there one-handed, doing my best to lodge my toes into the crack between bricks, a thought struck me. I could turn my mono-dextrous situation to my advantage if I was careful.

I rummaged in my jacket pocket with my free hand. It was entirely possible - if not expected given my current run of luck - that what I was hunting for was in the other pocket and out of reach. Still, you’ve got to catch a break occasionally and, as my fingers closed around the small packet, it seemed things were on the up. I fumbled open the packet and drew out the object I was after, holding it between my lips as I searched the pocket again. No. Empty. Somewhere in the distance God was heard to laugh.

What a bastard he is.

I was out of options. Time to swallow my pride and talk to my attacker. Straightening the cigarette in my mouth, I sighed and shouted up to him.

“Don’t suppose you’ve got a light?”

In hindsight I’m assuming he was one of those evangelical non-smokers. Otherwise, kicking at the one hand that was keeping me attached to this soot-stained tower when a simple “no” would have sufficed would have no justification at all.

I wondered on this sort of intolerance of others as I toppled backwards, if only to take my mind off the immutable facts of gravity.

2.

The air in the memorial garden was thick with black smoke, so I saw no problem adding more. “Smoking harms you and others around you” the pack assured me as I shoved it back into my jacket pocket. Without wanting to be presumptuous, the gravestone I was leaning on insisted that its occupant had been in the ground since ’74, so it was a safe bet that health issues were a low priority. He might chuckle if a few worms developed tumours though, so I puffed a cloud of smoke towards the earth and wished him well.

I loosened the black tie at my throat, letting some air in. It had been insufferably hot inside the church, the typical muggy air of a city summer hugging old stone. I’d sat at the back, feigning polite distance from the family and close friends but frankly just desperate for the draught from the open doors. Even in that slight breeze it had been sickeningly close; much hotter and I felt I’d be joining the deceased in their urns. The priest had been suffering too, wafting his surplice during the hymns, desperate for updraught. After the third or fourth time it occurred to me that he could have been naked underneath, and the thought disturbed me for the rest of the service. It seemed a touch sacrilegious somehow; surely trousers were a prerequisite when in the presence of the dead?

Little would surprise me as far as he was concerned: the thin red veins that spread across his cheeks and nose reminded me of a summer hiking with an Ordnance Survey map when I was still young enough to think it might be fun. Careful analysis of his face would probably lead to many hidden treasures; maybe that large eruption to the left of his mottled beak was the final resting place of the Grail? Or, more likely, his secret stash of appropriated altar wine. Judging by the accelerated speed of the service, he was clearly eager to get the body burned and return to his bottle. I egged him on.

We took our cue for the final hymn and, feeling I’d done my duty, I used the distraction to get out in the fresh air and sneak a fag.

Not that it was much cooler outside; a haze clung to the gravestones like syrup. The buzzing of a lawnmower that had hung under the words of the service had stopped, the gardener sitting down in the shade of a tree to pick at limp sandwiches from his plastic lunchbox.

Embers were floating from the mouth of the chimney above the crematorium, wafting their way towards civilisation. I wondered whether it was supposed to do that: a goodly quantity of her ashes were being spread whether she’d wanted it or not. Thinking about it, she would probably have been pleased. I’d barely known the woman, but had heard as many stories of her exploits as there were to be told. The “doyenne” of theatre had been self-proclaimed, as comfortable with the image of eccentric dame as she was skilled at portraying it. A faded folk icon to the glitter-and-camp brigade, destined to be remembered with trilled speeches and raised gin. Why they had chosen this dreary suburb to send her on her way was a mystery, but certainly she would have felt a touch of pride at being smeared across its dirty red brick and concrete. It was a streak of glamour on a mundane backcloth, scarlet lipstick on the mouth of a corpse.

People were beginning to appear at the chapel exit, black-clad mourners parading their grief in so overt and grotesque a manner that I fought the urge to applaud. One final drama to end them all.

“Bloody awful, isn’t it?”

Tom Harris’ ability to sneak up on me was one of his most redeeming features. Don’t get me wrong, it pisses me off something rotten, but it was undoubtedly the nicest of his bad qualities. The way he always managed to convince me to do something, for example, now that was really irritating.

“Come on, I’ll let you buy me a drink.”

“Yeah, all right.”

See? Infuriating.

I’d known Tom for more years than I care to count. One of the first theatre directors to put work my way - and indeed, keep offering it over the years - I felt I should class him as friend rather than employer. For his part we worked on a similar wavelength. He knew he could rely on me to do the job he was asking without the need for extensive direction - we just tended to look at characters in the same way. That and the fact I bought him wine when asked.

There’s a little more to it than that, but I don’t intend to get caught up in that story if at all possible. Suffice it to say we had considerable shared history.

We hit the pub a good round or so ahead of the other mourners, who had, no doubt, been delayed by a few days’ or so mutual backslapping. I bought Tom his preferred large glass of Cabernet and a pint of lager for myself - not that I don’t like wine, but I am very much the sort that feels a bit of a ponce ordering it in a pub. Pathetic? Certainly, but with the twenty or so years between us, Tom and I straddled that peculiar age barrier: he was just old enough to realise it was all nonsense, I still had sufficient youth to believe it important.

We hid away in a corner snug. While Tom and I could never quite resist attending events like this, we made a point of avoiding the company that inevitably came with them. We keep ourselves to ourselves.

“God, but I hate these old theatre bashes,” Tom sighed, scratching absently at the cropped beard he calls “silver” but a more uncharitable person might call grey.

“You love it, reminds you of ‘the old days’.”

“‘The old days’? Dear Lord... when did I get so bloody old that I possess eras?”

“Ages ago.”

“I suppose there’s a dreadful pleasure to be found in counting the empty seats around the tables, mentally ticking off those who’ve pegged it since the last get-together.”

“You’re a sick old bastard, you know that?”

Tom smiled.

“And you, Max, are a terrible hypocrite.”

Truth was, both of us liked hovering on the edges of the old circle; it was nostalgic. Tom and I did little theatre work these days, general circumstance having nudged us in a different direction. We both liked to keep a creative hand in now and then, writing the occasional review just to prove that we could. Generally though, we had other things on our minds.

First round sunk. Tom replaced it, and the cycle for the next few hours was set. By the time we left the pub it was dark and our rather self-conscious swagger had been replaced with a jaunty stumble that took out several of the coats hanging by the door and saw Tom nearly impale himself on a fibreglass guide dog that stood by the door hoping for charity donations.

“Down boy,” he said and we tumbled onto the pavement with limited physical injury but further wounding to our reputations.

Strolling along the street in the direction of the church and the hope of a taxi rank, we laughed at things without humour and tripped over absent stumbling blocks.

Just another patented Harris/Jackson skinful.

“It’s no good,” Tom muttered.

“What?” I replied, laughing inanely for some reason I can no longer recall.

“I’m going to have to pay a visit to a darkened corner.”

He scrabbled over the church wall, unzipping his jeans as he went, in that drunken sense of preparation, or perhaps just making sure he did so while he remembered it was necessary.

I sighed, chuckled again and attempted a nonchalant vault over the wall that resulted in nothing less than a grass-stained cheek and a bent cigarette. Getting quickly to my feet, I checked if Tom had noticed and was relieved to see that he had his back to me and was apologising to the deceased residents as he emptied his bladder.

I replaced my cigarette and strolled through the tombstones in his general direction, gazing up at the dark church building. It looked better at night, lit by spaced-out floodlights that gave it a fine dressing of gothic shadow but hid the dirt stains of years of traffic and industry. Once upon a time this would have been a focal building at the centre of a small village. Then suburbia came, ploughing through the countryside, subsuming all the smaller outposts it came to. One day the cities will eat everything.

A movement caught my eye by the church door. Darting behind the closest stone, I watched a group of people carrying a coffin. Tom was beginning to hum Miles Davis, something he has a habit of doing when he forgets not to.

I enjoyed a nice fruity curse and dashed towards him, trying my best to keep to the shadows of the far wall.

He was, thankfully, zipping himself up as I drew up behind him.

“What?” he said in a manner that was both indignant and too loud for my liking.

“Keep your mouth shut, we’ve got company,” I said, pointing towards the group of people a few hundred feet away.

They had a large Transit van. One of them was opening the doors as the others carried the coffin over.

“Hardly the most salubrious form of transport. Not to mention the wrong direction,” Tom whispered, and began tiptoeing towards them.

“Where do you think you’re going?” I asked, trying to keep up.

“I’m being nosey,” he replied, crouching rather unsteadily behind a gravestone no more than a healthy spit away from the front of the church.

I decided that giving him a good kicking was likely to draw attention so, pencilling it in for ten minutes’ time, I resigned myself to hiding behind the stone next door to his.

It wasn’t even as if they were up to anything particularly exciting. I mean, true, a Transit isn’t a preferred transport for coffins, not full ones anyway. That said, for all I knew, it happened all the time, leaving the hearse for more ceremonial occasions. What the family didn’t know was hardly likely to concern them. Then I realised what he’d meant about direction - why would you take a corpse away from a graveyard?

At that moment one of the men stumbled, twisting his ankle on a large stone that sat out of place on the gravel driveway. One of the others gave a panicked shout as the coffin slipped out of his grip, and I fought the instinctual urge to dash towards them as I watched the coffin drop to the ground.

The lid cracked open and a satin-wrapped body fell out. The men stared at the body for a moment, as if uncertain whether it might suddenly sit up and shout at them for being so clumsy. The man by the van, clearly the boss, marched over and clipped one of them across the shoulder.

“Pick her up, you clumsy bastards!”

The spell broke and, as one, they lifted her back into the coffin.

“Come on!” the boss said, shoving them towards the open back doors of the van.

They hoisted the coffin in, all concerns of gentility gone, shoving it towards the back with a clang of heavy wood against metal.

Two of the men jogged back to close the church doors while the boss walked around to the passenger door, climbing in as the driver started the engine.

Church closed, the others clambered into the back of the van, slamming the doors shut behind them as the driver reversed out and then drove off through the church gates. Both Tom and I ducked as the headlamps swept across the front of the stones we were hiding behind.

After a few moments we stood up.

“Well that was interesting,” Tom said.

“Worrying, certainly. You can’t get good staff these days, can you?”

Tom looked bemused.

“I think you’re missing something. What did you notice about the woman in the coffin?”

“Never seen her before in my life.”

“That’s not what I was asking, there was something particular about her.”

I leaned on the tombstone and lit a cigarette, to buy me a little time more than anything else.

“Other than the fact that she was being manhandled into the back of Transit van by the most thug-like undertakers operating in the Greater London area? Not much... She was in her thirties, blonde hair, about five and a half foot...” I took a drag of my cigarette while trying to think of something else. “Wrapped in a red satin sheet...”

Tom sighed.

“All true, but you’ve missed one rather obvious point.”

“Really?”

“Yes.” Tom put his hands in his pockets and strolled out onto the gravel drive. He was scanning the ground for something. “Aha!” he shouted and dropped to his haunches.

“What?” I was getting a touch impatient. Much more of this and I might have to call my secretary and have the Tom-kicking moved forward.

“A set of keys,” Tom replied, holding them up. “They came off that man’s belt when he fell over.”

“About the body, you infuriating git!”

“Oh.” Tom nodded, popping the keys in his pocket. “Well, you managed to describe what she looked like well enough, but there was one obvious feature you didn’t catch.”

He moved over to join me.

“She was breathing. Not a common habit among the dead.”

3.

After all the running around, hiding, and being generally weirded out, Tom and I were pretty much on our way towards sober (say somewhere in its suburbs following the “city centre” signs and keeping our eyes peeled for car parks), which seems ironic to me because any action or event capable of sobering me up at preternatural speed tends to be exactly the sort of thing where I need a stiff drink after. It’s good that Tom had the foresight to buy a nightclub a few years ago; it meant that - after a bit more stumbling around looking for a taxi - we had somewhere to go.

It wasn’t a big place: about thirty tables and a stage filled it to capacity. He could have fitted a few more punters in if he’d had a smaller bar, but Tom didn’t like to skimp on the important stuff. There was live music most nights, jazz and blues as a rule, although Tom could occasionally be caught unawares and end up with a little variety slipped onto the schedule behind his back. Generally though, if it didn’t have a horn section it wasn’t going to set foot on his stage. Tom was nothing if not a man of principle. His attitude had certainly paid off: the place was extremely popular and, as a result, he was hardly short of a shilling. Not that he had much hand in the day to day running of the place; he left that to Len Horowitz, his manager - a man with a wit so dry it would give a lizard cottonmouth. He was good at his job though, and the club’s reputation was strong enough to bear the occasional rude comment towards the clientele. I think most of them rather liked it. There is a universal rule among such establishments: get it right and the customers will do all the hard work, keep clear of fashionability and they’ll come to you. “Deadbeat” - something of an in-joke between Tom and I - was a place to go.

“Ah,” Len sighed, twitching his thick moustache in disgust as we leaned on the bar. “The only two regulars I haven’t the authority to bar. What’ll it be?”

“A brace of sturdy caipirinhas, I think. Don’t you, Max?”

“It would be exceedingly rude not to, Tom. Smash those limes, Len, show ’em who’s boss.”

“Oh they know, Mr Jackson. It’s Mr Harris here that sometimes get confused on that score.”

He went on the hunt for cachaça and we for a corner booth.

“So,” Tom said as we sat down out of the way of the few diehards that were still loitering near the stage, “that was all very intriguing wasn’t it?”

“One word for it.”

He pulled the keys he’d found out of his pocket and began to examine them.

“Fascinating... there’s so much you can tell from the objects people carry around with them every day, little clues to their lives and habits. Even with only a cursory examination, in far from perfect lighting, I can make a number of insightful assumptions about the owner of these keys. He has money.” He held up a car key. “The car that belongs to this doesn’t come cheap. He keeps himself fit and works in a job that requires a uniform: there are two locker keys, you see?”

I nodded, just to keep him happy.

“He’s either a drinker or extremely short-sighted: there are a number of scratches and dents that suggest repeated misaligning of key and lock.”

He held the keys up to his nose and sniffed, raised an eyebrow, then sniffed again.

“Very distinctive odour.” He put on his best “ruminating” face and then slammed the keys on the table. “Embalming fluid. He works in an undertakers.”

He’d timed it perfectly; Len placed the caipirinhas in front of us right on the full stop.

“Very impressive, Holmes,” I said, taking a sip of my drink, “to be able to tell all of that from just a ‘cursory examination’. I would be in awe of your deductive abilities, were it not for the fact that I too can read.” I held up the leather key fob with the name and address of an undertaking firm on it.

“Oh, you saw that, did you?”

“Yes, you theatrical old queen. That and the fact they were pissing about with coffins led me to believe they weren’t fishmongers. Where did you get the rest from?”

“Made it up, can’t see a thing in this light. How was my delivery though?”

“So ham it would unnerve Jewish people. Congratulations.”

“Thank you.” He performed a half bow.

We drank our cocktails for a few moments, Tom waiting for me to suggest we investigate further, me refusing to give him the satisfaction. I knew impatience would force him do it himself eventually.

“So,” he said, “you reckon we should look into it?”

“Why? Nothing to do with us.”

“Don’t tell me you’re not interested.”

“Not particularly.”

A blatant lie, but I was damned if I was going to roll over straight away.

“What else have we got to do? It would pass the time, if nothing else.”

Which was true. Both Tom and I had been in a considerable rut of late. Deadbeat ran itself; in fact whenever Tom tried to get too proactive he ended up getting in the way. I wasn’t working. The days were starting to get a little monotonous for both of us. “Why don’t they just go to the police?” you ask. Well... suffice it to say that we couldn’t. For personal reasons, talking to the police would be a Really Bad Idea.

I picked up the keys and made a show of sighing and rolling my eyes.

“All right then, we’ll have a little nose around.”

“Excellent!” Tom slapped the table with his palms and got to his feet.

“I’ll get us more drinks by way of celebration.”

Which, unsurprisingly, is exactly how all of our worst ideas start out.

4.

Start as you mean to go on. A couple of hours later and I had entered that state of mental shutdown that a night at the bar often brings, staring vacantly as a handful of ice cracked and melted in the tumbler in front of me, much like my brain.

As is always the way when I straddle that transient line between consciousness and utter oblivion, my mind started to fart images at me: always the water, that slap of ice to the face, the roar deep inside the eardrums, the splitting pain in my chest as the heart fights to keep beating, the distant bellow of horns. And at that point more drink will only make them clearer, not blot them out completely. Still, you refresh your glass, work through it, keep running in the only direction you know: towards darkness and a lack of responsibility.

Right now even telling this story is too much work for my liking. You don’t know who I am, not really. Sat there questioning my motivations and thoughts... wondering why... There’s so much I could tell you, things unsaid... perhaps I should just let it all come out. No more secrets. But then, while some things would be clearer, the rest would be worse... If you knew everything about me you wouldn’t still be here. You’d have started screaming long before now.

Christ, drink makes me waffle...

2

TOM

1.

Finley Peter Dunne, the American writer and humorist, was a fiercely wise chap. “Alcohol,” he said, “is necessary for a man so that he can have a good opinion of himself, undisturbed by the facts.” When the clock drags its heels towards the early hours of morning it’s a thought that often rolls around my head. Sat there on one of the barstools watching the last soldiers fall from the assault of grape and grain, limping wounded onto the no-man’s-land of Soho for a taxi to take them home, I wonder on the truth of his words. Do I drink to bolster low self-esteem? Do I drink to wear down the edges of memory? Is it a crutch that maintains my ability to walk through this life with some degree of efficacy?

The thoughts haunt me, so much so that I pound the hell out of them with a few stiff measures of brandy. Nobody needs that sort of depressing nonsense in their brain when they’re trying to have a good night. Takes all the fun out of it.

That night it wasn’t an issue. I had more than enough to occupy the scant few grey cells I had mercifully spared from the booze. It had been some considerable time since anything had provided so much as a buzz of mental interest. Life can become interminably dull if you allow it.

Max, as per usual, passed out across the table we’d been sitting at and I had the boys bundle him home. There will come a time when I will have to insist that he move in upstairs, if only to save petrol.

Watching the hustle and bustle of the staff clearing down, sweeping up and generally turning the club back to its previous state, as if it were a crime scene that we wished to disguise, I decided to shut myself in my office and leave them to it. I’m hopeless with a dustpan and I’d only get in the way. Besides, the office is where I keep most of my record collection and the speakers are wired up perfectly. It is the best place to lose myself in music that I know. I have been assured by Len that it would also be an ideal place for any clerical work involving the club, accounts and general paperwork, but I’ve seen no reason to prove that as yet. In my mind, offices lose some of their charm if you start working in them.

I slipped Oliver Nelson’s Swiss Suite onto the turntable and turned the volume up enough to dissuade anyone from knocking on the door and interfering with my mood. Thus assured of not losing my reputation by being observed, I brewed a cafetière of strong coffee and turned my little laptop on.

People assume I can’t operate a computer. I must have a Luddite air to me. It’s true enough that they baffle me frequently and many’s the time when I have had an extremely strong urge to hurl the thing across the room. But that’s technology for you, you take the rough with the smooth. I wouldn’t be without it and - keep it under your hat - I actually write a couple of music blogs (one on classical and one on jazz) under a pseudonym. It pays very little but then I don’t do it for the money, it’s just fun to waffle about one’s passions...

I checked my emails - offers of penis enlargement and cash-rich Nigerians for the most part; my correspondence is never less than scintillating - and then wandered aimlessly online while sipping my coffee. After a ten-minute stroll through the sites I usually frequent, by way of asserting to myself that what I was hunting for was most probably nothing of interest and therefore not worth rushing over, I tapped “Lloyd & Bryson Undertakers” into a search engine and glanced at the page of results. It assured me that the “and” had been unnecessary as it searched all phrases by default, which was all well and good if it could have shown me the fruit of such confidence by way of a useful link. As it was, there was a list of funeral homes in America, none of which could be of the slightest relevance.

I couldn’t help but think that I was letting the spirit of Philip Marlowe down.

Bringing up the phone directory page, I managed to pin the office of the undertakers to an address in Kentish Town. Not far from the church then. That was something - at least we now knew where it was.

I made a new search: Kentish Town undertakers... plenty of those - they’re dropping like flies in Camden. I hit upon a link to a message board where posters were sharing their grief in the cosy anonymity of the Internet. One woman’s message contained a list of agonies regarding her husband, who had clearly been struck fatally ill and had gone from fit as a fiddle to dead and buried within a matter of weeks. She made a reference to an undertaker that had been recommended to her via the health insurance company she had a policy with, but it could have been anyone. She had nothing but praise for them and made no reference to Transit vans or midnight flits.

This really was getting us nowhere.

To hell with the Internet, we needed to expend shoe leather.

I dialled Max’s number and left a message on his answer machine telling him to meet me at the church in the morning. I suggested a not-so-distant time that I knew he would deeply disapprove of. I also knew that the persistent beeping of his machine would ensure he woke up to meet the appointment. His answer machine takes no prisoners -I know, I bought it for him.

Poor Max, so easily led...

I should tell the story of how we first met, if only because I know it would irritate him hugely.

Max often tells people that he and I worked together in theatre, which is not entirely true. Well... it’s not true at all, actually, but I know why he says it. Certainly we both have a history as far as the stage is concerned, and that shared background added to the ease with which we hit it off and grew close. I was a child in Stratford-upon-Avon; I grew up on Shakespeare and sonnets (as well as Hemingway and pulp war novels - my literary upbringing was a field of highs and lows). I was there in the sixties when Peter Hall kicked The Bard up the arse and gave the Royal Shakespeare Company the birth it needed. Shakespeare was as cool as Miles Davis, and they were my poster idols as I surfed adolescence. I worked as a writer and director in theatre for many years, in between more lucrative employment. Max has the handicap of being younger than me, but nonetheless found himself on a similar path: a trained actor hacking out a living in profit-share theatre, the sort of shows that have larger casts than audiences, occasionally paying for food with the odd appearance on television.

By the time we crossed paths it was a lifestyle that had pretty much been squeezed out of both of us. I had recently bought the club and Max... Well, Max had been drifting.

He wasn’t always the well-adjusted gentleman you see today (yes, I’m being sarcastic). When I first clapped eyes on him he was a ragged and weary young man. He had all the confidence of a whipped dog, carrying himself as if he expected to be jumped upon and beaten at any moment. Nervous then, yes, but it was more than that. His awkwardness and perpetually twitching sense of imminent danger was not a temporary fixture, this was how he was. A man scared to exist in his own skin.

I was attending a fringe show in the dingy top room of a pub in Camden, all black painted walls and the fug of tobacco and old beer. I knew one of the cast, and out of a misguided sense of loyalty I had decided to turn up and show a little support.

After an hour or so of watching Romeo and Juliet restaged as a lesbian love tryst (with the nurse a jaded transsexual replete in goatee and Laura Ashley) I was losing the will to live, and determined to bail out of this creative death-pit the moment the lights went up for the interval. I spotted Max in the row just in front of mine. Like me he was loitering in the back seats, keeping his head down (in my case I had no wish to announce myself, even less now it was clear that I would be incapable of surviving the whole performance). His hair was a good deal longer than he favours these days, curly and spiked in a manner that suggested lack of treatment rather than the swirling fringe sculptures that seem popular today. He was wearing a long overcoat that he tugged around himself like a blanket, as if desperate to lose himself in one of its pockets. His attention to the stage was minimal. He glanced at it now and then in a rather dutiful manner but he wasn’t even giving it enough attention to loathe it. It was something that just happened to be going on in the same room. He spent more time looking around, ignoring the mangled verse and histrionics in favour of analysing the chipped plaster walls and the frayed set dressing. He was a man gripped by discomfort. There were a few momentary exceptions whenever one of the female cast entered. Then, and only then, his attention was total. I assumed he was there out of a sense of duty, much like me. That aside, his discomfort was so pronounced I couldn’t help but watch him closely.

When the interval finally raised its slovenly head and the house lights revealed the small gathering of bewildered audience - friends and mothers all, no doubt - I found myself following him down the stairs into the bar. I was intrigued by him and wanted to know more.

Rather than take a place at the bar as most of the audience did (hoping to drink enough to make the second half tolerable), he walked straight out onto the street. I did the same and put a little spurt on so as to draw level with him.

“Two theatre lovers, alike in dignity,” I said, mangling poor old Bill Shakespeare no more than the actors had. “I take it you hated it as much as me?”

He flinched, that sense of unease and fearfulness given full rein for just a moment before he snapped it back down and smiled. “I heard Shakespeare screaming in agony five minutes in.”

“Apparently they try and up the ante in the second half with a naked love scene. The papers were full of it.”

“Romeo could fire ping-pong balls into the crowd with all the skill of a Bangkok stripper and it still wouldn’t stop me from falling asleep.”

He didn’t stop walking - that would have meant embracing the conversation, which he was clearly still unwilling to do - but he was polite enough to slow down a little so that walking and talking were easier.

“I know one of the cast,” I said, eager to keep the conversation moving, “otherwise I wouldn’t have bothered chancing it.”

“Not one of the leads?” he asked.

“No, thank God, I wouldn’t have admitted it if I did. The nurse.”

He laughed. “He looks cracking in a frock.”

“Yes, one of the prouder lines on his CV I’m sure.” I had hoped he was going to admit knowing the woman he had been so drawn to. No such luck. Perhaps he needed lubricating. “Fancy a drink?”

I nodded towards a pub across the road. That worried look returned to his face; no doubt he thought I was trying to pull him, arrogant bugger. He need hardly have worried on that score.

“Er... no, thanks though, I need to be getting home really.”

He started walking a little quicker and I realised I needed to play dirty in order to keep him from vanishing. The thing is, I had a hunch what it was about him that had drawn my attention - beyond his bizarre mannerisms -and the only way I could think of to stop him was to trust my instincts and use it. There was something else the two of us shared beyond an appreciation of what made truly awful theatre and, if I was right, the realisation that it was a mutual affliction would be enough for him to stop for a second and hear me out.

Now, this is tricky. You see, there is indeed something unusual about Max, and I was right when I thought I sensed it in him on that first meeting. Still, it is hardly my place to announce it. You’ll just have to trust me when I say that there is a reason he drew my eye and that it would be of benefit to both of us to sit down over some finely chilled alcohol and discuss it. You will have to accept that, for now at least, you do not need to know what that is.

It’s enough to say that my gut instincts about him had been right and, after a panicked moment when I thought he might run anyway - so concerned was he that he had been so easily discovered - he relaxed and we headed over the road for a drink.

Secrets. My entire life is complicated by secrets.

We talked about lots of things. He told me about his theatrical past. He also admitted he’d been there to watch the young woman forced into Mercutio’s doublet and hose. I got the impression their relationship had been a little more than just having worked together, but he refused to be drawn on the details. What was clear was that he had no intention of being seen by her and would have done a runner in the interval whether the play had been good or not.

He talked about his background in Yorkshire, his childhood, how he had come to be in London... He talked about everything. It is always the way with someone so tensed up, someone who has become so nervously clenched as to be almost physically deformed by it: when they are given the chance to unwind they do so with such violence that one is advised to just sit back and allow it, adding more alcohol and the odd supportive nod or grunt as and when it seems required. We got heroically drunk. Drunk enough in fact that we decided the only way forward, after groaning at the depressive death-knell of the bell behind the bar, was to make our way to the club and drink some more.

I am only too aware, thinking back on the two of us stumbling through the streets, how the template was set for so many of our nights to come. We are creatures of habit, Max and I, and that was the night that formed it all.

Back at the club, I marvelled at how the terrified young man I had first spotted hours earlier had become transformed into this whirling dervish, dancing on his own to the sound of Dixieland. Fists raised in the air and face grimly set into a frown of deep concentration as he moved like Cab Calloway.

It goes without saying that Len had his reservations. It is an awkward conflict of interests for a bar manager when the one individual that could be defined as worthy of removal is there at the owner’s invitation, and therefore above the law.

“That bastard’s making eyes at me!” Max shouted at one point (though the band were between tunes and he didn’t need to raise his voice to be heard).

“Len is a man of infinite intolerance,” I assured him, “don’t let it bother you.”

Max grinned, necked the gin and tonic he had been working on and spiralled back onto the dance floor as the band picked up again. He came to a halt in the centre of the room - regressed to the showy little performer he had been so many years ago, before financial failure and perpetual joblessness had started to knock it out of him - held up his hands and prepared to make a speech. Before he could so much as utter a syllable though, his face drooped on its bones and a look of absolute confusion poured itself into his eyes. He spun around and, in an act of pure abandon that makes him cringe heartily whenever I mention it -which, of course, means I mention it frequently - he threw up into the bell of the bass saxophone behind him. The mortified saxophonist - a pale and timid man who had been muscling up to lead into “Sweet Georgia Brown” - gave a roar of disgust and dropped the slopping horn. Max caught it, face still pressed against the brass rim of its bell, and fell back on the floor. He sat, legs splayed, saxophone hugged to his belly as the now-silent club fixed its attention on him.

That’s how I first met Max Jackson.