2,73 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Delphi Classics

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Delphi Series Seven

- Sprache: Englisch

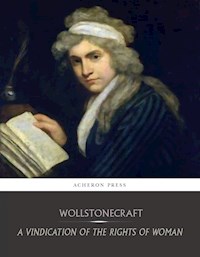

English writer, philosopher and pioneering advocate of women's rights, Mary Wollstonecraft wrote novels, treatises, a travel narrative, a history of the French Revolution and a children's book. In her landmark feminist text, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), Wollstonecraft argued that women are not naturally inferior to men, but appeared to be only because they lacked education. She called for men and women to be treated equally, paving the way for the emergence of the feminist movement at the turn of the twentieth century. This comprehensive eBook presents Wollstonecraft’s complete fictional works, with numerous illustrations, rare texts, informative introductions and the usual Delphi bonus material. (Version 1)

* Beautifully illustrated with images relating to Wollstonecraft’s life and works

* Concise introductions to the novels and other texts

* All the novels, with individual contents tables

* Images of how the books were first published, giving your eReader a taste of the original texts

* Excellent formatting of the texts

* Includes Wollstonecraft’s complete pamphlets

* ‘A Vindication of the Rights of Man’ in presented with an appendix of Burke’s ‘Reflections on the Revolution in France’

* Includes Wollstonecraft’s posthumously published Works

* Features three biographies, including the author’s husband’s controversial memoir - discover Wollstonecraft’s personal and literary life

* Scholarly ordering of texts into chronological order and literary genres

Please visit www.delphiclassics.com to browse through our range of exciting titles

CONTENTS:

The Fiction

MARY: A FICTION

MARIA; OR, THE WRONGS OF WOMAN

THE CAVE OF FANCY

The Children’s Book

ORIGINAL STORIES FROM REAL LIFE

The Non-Fiction

THOUGHTS ON THE EDUCATION OF DAUGHTERS

A VINDICATION OF THE RIGHTS OF MEN

A VINDICATION OF THE RIGHTS OF WOMAN

AN HISTORICAL AND MORAL VIEW OF THE FRENCH REVOLUTION; AND THE EFFECT IT HAS PRODUCED IN EUROPE

LETTERS WRITTEN DURING A SHORT RESIDENCE IN SWEDEN, NORWAY, AND DENMARK

ON POETRY, AND OUR RELISH FOR THE BEAUTIES OF NATURE

LETTER ON THE PRESENT CHARACTER OF THE FRENCH NATION

FRAGMENT OF LETTERS ON THE MANAGEMENT OF INFANTS

LETTERS TO MR. JOHNSON, BOOKSELLER, IN ST. PAUL’S CHURCH-YARD

LESSONS

HINTS

LETTERS

The Biographies

MEMOIRS OF THE AUTHOR OF A VINDICATION OF THE RIGHTS OF WOMAN by William Godwin

MARY WOLLSTONECRAFT by Elizabeth Robins Pennell

A BRIEF SKETCH OF THE LIFE OF MARY WOLLSTONECRAFT

Please visit www.delphiclassics.com to browse through our range of exciting titles or to purchase this eBook as a Parts Edition of individual eBooks

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 3277

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

The Complete Works of

MARY WOLLSTONECRAFT

(1759-1797)

Contents

The Fiction

MARY: A FICTION

MARIA; OR, THE WRONGS OF WOMAN

THE CAVE OF FANCY

The Children’s Book

ORIGINAL STORIES FROM REAL LIFE

The Non-Fiction

THOUGHTS ON THE EDUCATION OF DAUGHTERS

A VINDICATION OF THE RIGHTS OF MEN

A VINDICATION OF THE RIGHTS OF WOMAN

AN HISTORICAL AND MORAL VIEW OF THE FRENCH REVOLUTION; AND THE EFFECT IT HAS PRODUCED IN EUROPE

LETTERS WRITTEN DURING A SHORT RESIDENCE IN SWEDEN, NORWAY, AND DENMARK

ON POETRY, AND OUR RELISH FOR THE BEAUTIES OF NATURE

LETTER ON THE PRESENT CHARACTER OF THE FRENCH NATION

FRAGMENT OF LETTERS ON THE MANAGEMENT OF INFANTS

LETTERS TO MR. JOHNSON, BOOKSELLER, IN ST. PAUL’S CHURCH-YARD

LESSONS

HINTS

LETTERS

The Biographies

MEMOIRS OF THE AUTHOR OF A VINDICATION OF THE RIGHTS OF WOMAN by William Godwin

MARY WOLLSTONECRAFT by Elizabeth Robins Pennell

A BRIEF SKETCH OF THE LIFE OF MARY WOLLSTONECRAFT

The Delphi Classics Catalogue

© Delphi Classics 2016

Version 1

The Complete Works of

MARY WOLLSTONECRAFT

By Delphi Classics, 2016

COPYRIGHT

Complete Works of Mary Wollstonecraft

First published in the United Kingdom in 2016 by Delphi Classics.

© Delphi Classics, 2016.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

ISBN: 978 1 78656 045 2

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: [email protected]

www.delphiclassics.com

Parts Edition Now Available!

Love reading Mary Wollstonecraft?

Did you know you can now purchase the Delphi Classics Parts Edition of this author and enjoy all the novels, plays, non-fiction books and other works as individual eBooks? Now, you can select and read individual novels etc. and know precisely where you are in an eBook. You will also be able to manage space better on your eReading devices.

The Parts Edition is only available direct from the Delphi Classics website.

For more information about this exciting new format and to try free Parts Edition downloads, please visit this link.

The Fiction

Mary Wollstonecraft was born on 27 April 1759 in Spitalfields, London. She was the second of seven children of Edward John Wollstonecraft and Elizabeth Dixon.

MARY: A FICTION

The only complete novel by Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary was written while she was working as a governess in Ireland. It was published in 1788 shortly after her summary dismissal and her decision to embark on a writing career, a precarious and disreputable profession for women in eighteenth century Britain. Inspired by Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s idea that geniuses are self-taught, Wollstonecraft presents Mary, a self-taught genius, as the central character of her novel. Helping to redefine genius, Wollstonecraft describes Mary as independent and capable of defining femininity and marriage for herself. It is Mary’s “strong, original opinions” and her resistance to “conventional wisdom” that mark her as a genius. Through this heroine the author critiques marriage, contemporary sensibility and its damaging effects on women. Mary rewrites the traditional romance plot through its reimagination of gender relations and female sexuality. Yet, because Wollstonecraft employs the genre of sentimentalism to critique sentimentalism itself, the novel at times reflects the same flaws of sentimentalism that she attempts to expose.

Wollstonecraft would later repudiate the novel, writing that it was laughable. However, critics have since argued that, despite its faults, the representation of an energetic, unconventional, opinionated, rational, female genius (the first of its kind in English literature) within a new kind of romance is an important development in the history of the novel as it helped shape an emerging feminist discourse.

The novel opens with a description of the conventional and loveless marriage between the heroine’s mother and father. Eliza, Mary’s mother, is obsessed with novels, rarely considers anyone but herself, and favours Mary’s brother. She neglects her daughter, who educates herself using only books and the natural world. Neglected by her family, Mary devotes much of her time to charity. When her brother suddenly dies, leaving Mary heir to the family’s fortune, her mother finally takes an interest in her. She is taught ‘accomplishments’ such as dancing to attract suitors. However, Mary’s mother soon sickens and requests on her deathbed that her daughter should wed Charles, a wealthy man she has never met. Stunned and unable to refuse, Mary agrees. Immediately after the ceremony, Charles departs for the Continent. To escape a family that does not share her values, Mary befriends Ann, a local girl, who educates her still further. Mary becomes attached to Ann, who is in the grip of an unrequited love and does not reciprocate Mary’s feelings. Ann’s family falls into poverty and is on the brink of losing their home, but Mary is able to pay off their debts after her marriage to Charles, who allows her limited control over her money.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s philosophical treatise on education, Emile (1762), was a major literary influence for Wollstonecraft. A few months before starting the novel, she wrote to her sister Everina: “I am now reading Rousseau’s Emile, and love his paradoxes... however he rambles into that chimerical world in which I have too often wandered... He was a strange inconsistent unhappy clever creature — yet he possessed an uncommon portion of sensibility and penetration… Rousseau chuses a common capacity to educate — and gives as a reason, that a genius will educate itself”. When Mary was published, the title page included a quotation from Rousseau: “L’exercice des plus sublimes vertus éleve et nourrit le génie” (the exercise of the most sublime virtues raises and nourishes genius). Therefore, the novel is generally considered an early example of a bildungsroman, or novel of education.

Published by Joseph Johnson, Mary was moderately successful and sections of the text were included in several collections of sentimental extracts that were popular at the time, such as The Young Gentleman and Lady’s Instructor (1809). However, the publisher was still trying to sell copies in the 1790’s and consistently listed it in the advertisements for her other works. Mary was not reprinted until the 1970’s, when scholars became interested in Wollstonecraft and women’s writing more generally.

The first edition’s title page

CONTENTS

ADVERTISEMENT.

CHAP. I.

CHAP. II.

CHAP. III.

CHAP. IV.

CHAP. V.

CHAP. VI.

CHAP. VII.

CHAP. VIII.

CHAP. IX.

CHAP. X.

CHAP. XI.

CHAP. XII.

CHAP. XIII.

CHAP. XIV.

CHAP. XV.

CHAP. XVI.

CHAP. XVII.

CHAP. XVIII.

CHAP. XIX.

CHAP. XX.

CHAP. XXI.

CHAP. XXII.

CHAP. XXIII.

CHAP. XXIV.

CHAP. XXV.

CHAP. XXVI.

CHAP. XXVII.

CHAP. XXVIII.

CHAP. XXIX.

CHAP. XXX.

CHAP. XXXI.

Rousseau’s Julie, or the New Heloise (1761), from which Wollstonecraft drew the epigraph for ‘Mary’

ADVERTISEMENT.

In delineating the Heroine of this Fiction, the Author attempts to develop a character different from those generally portrayed. This woman is neither a Clarissa, a Lady G —— , nor a Sophie. — It would be vain to mention the various modifications of these models, as it would to remark, how widely artists wander from nature, when they copy the originals of great masters. They catch the gross parts; but the subtile spirit evaporates; and not having the just ties, affectation disgusts, when grace was expected to charm.

Those compositions only have power to delight, and carry us willing captives, where the soul of the author is exhibited, and animates the hidden springs. Lost in a pleasing enthusiasm, they live in the scenes they represent; and do not measure their steps in a beaten track, solicitous to gather expected flowers, and bind them in a wreath, according to the prescribed rules of art.

These chosen few, wish to speak for themselves, and not to be an echo — even of the sweetest sounds — or the reflector of the most sublime beams. The paradise they ramble in, must be of their own creating — or the prospect soon grows insipid, and not varied by a vivifying principle, fades and dies.

In an artless tale, without episodes, the mind of a woman, who has thinking powers is displayed. The female organs have been thought too weak for this arduous employment; and experience seems to justify the assertion. Without arguing physically about possibilities — in a fiction, such a being may be allowed to exist; whose grandeur is derived from the operations of its own faculties, not subjugated to opinion; but drawn by the individual from the original source.

CHAP. I.

Mary, the heroine of this fiction, was the daughter of Edward, who married Eliza, a gentle, fashionable girl, with a kind of indolence in her temper, which might be termed negative good-nature: her virtues, indeed, were all of that stamp. She carefully attended to the shews of things, and her opinions, I should have said prejudices, were such as the generality approved of. She was educated with the expectation of a large fortune, of course became a mere machine: the homage of her attendants made a great part of her puerile amusements, and she never imagined there were any relative duties for her to fulfil: notions of her own consequence, by these means, were interwoven in her mind, and the years of youth spent in acquiring a few superficial accomplishments, without having any taste for them. When she was first introduced into the polite circle, she danced with an officer, whom she faintly wished to be united to; but her father soon after recommending another in a more distinguished rank of life, she readily submitted to his will, and promised to love, honour, and obey, (a vicious fool,) as in duty bound.

While they resided in London, they lived in the usual fashionable style, and seldom saw each other; nor were they much more sociable when they wooed rural felicity for more than half the year, in a delightful country, where Nature, with lavish hand, had scattered beauties around; for the master, with brute, unconscious gaze, passed them by unobserved, and sought amusement in country sports. He hunted in the morning, and after eating an immoderate dinner, generally fell asleep: this seasonable rest enabled him to digest the cumbrous load; he would then visit some of his pretty tenants; and when he compared their ruddy glow of health with his wife’s countenance, which even rouge could not enliven, it is not necessary to say which a gourmand would give the preference to. Their vulgar dance of spirits were infinitely more agreeable to his fancy than her sickly, die-away languor. Her voice was but the shadow of a sound, and she had, to complete her delicacy, so relaxed her nerves, that she became a mere nothing.

Many such noughts are there in the female world! yet she had a good opinion of her own merit, — truly, she said long prayers, — and sometimes read her Week’s Preparation: she dreaded that horrid place vulgarly called hell, the regions below; but whether her’s was a mounting spirit, I cannot pretend to determine; or what sort of a planet would have been proper for her, when she left her material part in this world, let metaphysicians settle; I have nothing to say to her unclothed spirit.

As she was sometimes obliged to be alone, or only with her French waiting-maid, she sent to the metropolis for all the new publications, and while she was dressing her hair, and she could turn her eyes from the glass, she ran over those most delightful substitutes for bodily dissipation, novels. I say bodily, or the animal soul, for a rational one can find no employment in polite circles. The glare of lights, the studied inelegancies of dress, and the compliments offered up at the shrine of false beauty, are all equally addressed to the senses.

When she could not any longer indulge the caprices of fancy one way, she tried another. The Platonic Marriage, Eliza Warwick, and some other interesting tales were perused with eagerness. Nothing could be more natural than the developement of the passions, nor more striking than the views of the human heart. What delicate struggles! and uncommonly pretty turns of thought! The picture that was found on a bramble-bush, the new sensitive-plant, or tree, which caught the swain by the upper-garment, and presented to his ravished eyes a portrait. — Fatal image! — It planted a thorn in a till then insensible heart, and sent a new kind of a knight-errant into the world. But even this was nothing to the catastrophe, and the circumstance on which it hung, the hornet settling on the sleeping lover’s face. What a heart-rending accident! She planted, in imitation of those susceptible souls, a rose bush; but there was not a lover to weep in concert with her, when she watered it with her tears. — Alas! Alas!

If my readers would excuse the sportiveness of fancy, and give me credit for genius, I would go on and tell them such tales as would force the sweet tears of sensibility to flow in copious showers down beautiful cheeks, to the discomposure of rouge, &c. &c. Nay, I would make it so interesting, that the fair peruser should beg the hair-dresser to settle the curls himself, and not interrupt her.

She had besides another resource, two most beautiful dogs, who shared her bed, and reclined on cushions near her all the day. These she watched with the most assiduous care, and bestowed on them the warmest caresses. This fondness for animals was not that kind of attendrissement which makes a person take pleasure in providing for the subsistence and comfort of a living creature; but it proceeded from vanity, it gave her an opportunity of lisping out the prettiest French expressions of ecstatic fondness, in accents that had never been attuned by tenderness.

She was chaste, according to the vulgar acceptation of the word, that is, she did not make any actual faux pas; she feared the world, and was indolent; but then, to make amends for this seeming self-denial, she read all the sentimental novels, dwelt on the love-scenes, and, had she thought while she read, her mind would have been contaminated; as she accompanied the lovers to the lonely arbors, and would walk with them by the clear light of the moon. She wondered her husband did not stay at home. She was jealous — why did he not love her, sit by her side, squeeze her hand, and look unutterable things? Gentle reader, I will tell thee; they neither of them felt what they could not utter. I will not pretend to say that they always annexed an idea to a word; but they had none of those feelings which are not easily analyzed.

CHAP. II.

In due time she brought forth a son, a feeble babe; and the following year a daughter. After the mother’s throes she felt very few sentiments of maternal tenderness: the children were given to nurses, and she played with her dogs. Want of exercise prevented the least chance of her recovering strength; and two or three milk-fevers brought on a consumption, to which her constitution tended. Her children all died in their infancy, except the two first, and she began to grow fond of the son, as he was remarkably handsome. For years she divided her time between the sofa, and the card-table. She thought not of death, though on the borders of the grave; nor did any of the duties of her station occur to her as necessary. Her children were left in the nursery; and when Mary, the little blushing girl, appeared, she would send the awkward thing away. To own the truth, she was awkward enough, in a house without any play-mates; for her brother had been sent to school, and she scarcely knew how to employ herself; she would ramble about the garden, admire the flowers, and play with the dogs. An old house-keeper told her stories, read to her, and, at last, taught her to read. Her mother talked of enquiring for a governess when her health would permit; and, in the interim desired her own maid to teach her French. As she had learned to read, she perused with avidity every book that came in her way. Neglected in every respect, and left to the operations of her own mind, she considered every thing that came under her inspection, and learned to think. She had heard of a separate state, and that angels sometimes visited this earth. She would sit in a thick wood in the park, and talk to them; make little songs addressed to them, and sing them to tunes of her own composing; and her native wood notes wild were sweet and touching.

Her father always exclaimed against female acquirements, and was glad that his wife’s indolence and ill health made her not trouble herself about them. She had besides another reason, she did not wish to have a fine tall girl brought forward into notice as her daughter; she still expected to recover, and figure away in the gay world. Her husband was very tyrannical and passionate; indeed so very easily irritated when inebriated, that Mary was continually in dread lest he should frighten her mother to death; her sickness called forth all Mary’s tenderness, and exercised her compassion so continually, that it became more than a match for self-love, and was the governing propensity of her heart through life. She was violent in her temper; but she saw her father’s faults, and would weep when obliged to compare his temper with her own. — She did more; artless prayers rose to Heaven for pardon, when she was conscious of having erred; and her contrition was so exceedingly painful, that she watched diligently the first movements of anger and impatience, to save herself this cruel remorse.

Sublime ideas filled her young mind — always connected with devotional sentiments; extemporary effusions of gratitude, and rhapsodies of praise would burst often from her, when she listened to the birds, or pursued the deer. She would gaze on the moon, and ramble through the gloomy path, observing the various shapes the clouds assumed, and listen to the sea that was not far distant. The wandering spirits, which she imagined inhabited every part of nature, were her constant friends and confidants. She began to consider the Great First Cause, formed just notions of his attributes, and, in particular, dwelt on his wisdom and goodness. Could she have loved her father or mother, had they returned her affection, she would not so soon, perhaps, have sought out a new world.

Her sensibility prompted her to search for an object to love; on earth it was not to be found: her mother had often disappointed her, and the apparent partiality she shewed to her brother gave her exquisite pain — produced a kind of habitual melancholy, led her into a fondness for reading tales of woe, and made her almost realize the fictitious distress.

She had not any notion of death till a little chicken expired at her feet; and her father had a dog hung in a passion. She then concluded animals had souls, or they would not have been subjected to the caprice of man; but what was the soul of man or beast? In this style year after year rolled on, her mother still vegetating.

A little girl who attended in the nursery fell sick. Mary paid her great attention; contrary to her wish, she was sent out of the house to her mother, a poor woman, whom necessity obliged to leave her sick child while she earned her daily bread. The poor wretch, in a fit of delirium stabbed herself, and Mary saw her dead body, and heard the dismal account; and so strongly did it impress her imagination, that every night of her life the bleeding corpse presented itself to her when the first began to slumber. Tortured by it, she at last made a vow, that if she was ever mistress of a family she would herself watch over every part of it. The impression that this accident made was indelible.

As her mother grew imperceptibly worse and worse, her father, who did not understand such a lingering complaint, imagined his wife was only grown still more whimsical, and that if she could be prevailed on to exert herself, her health would soon be re-established. In general he treated her with indifference; but when her illness at all interfered with his pleasures, he expostulated in the most cruel manner, and visibly harassed the invalid. Mary would then assiduously try to turn his attention to something else; and when sent out of the room, would watch at the door, until the storm was over, for unless it was, she could not rest. Other causes also contributed to disturb her repose: her mother’s luke-warm manner of performing her religious duties, filled her with anguish; and when she observed her father’s vices, the unbidden tears would flow. She was miserable when beggars were driven from the gate without being relieved; if she could do it unperceived, she would give them her own breakfast, and feel gratified, when, in consequence of it, she was pinched by hunger.

She had once, or twice, told her little secrets to her mother; they were laughed at, and she determined never to do it again. In this manner was she left to reflect on her own feelings; and so strengthened were they by being meditated on, that her character early became singular and permanent. Her understanding was strong and clear, when not clouded by her feelings; but she was too much the creature of impulse, and the slave of compassion.

CHAP. III.

Near her father’s house lived a poor widow, who had been brought up in affluence, but reduced to great distress by the extravagance of her husband; he had destroyed his constitution while he spent his fortune; and dying, left his wife, and five small children, to live on a very scanty pittance. The eldest daughter was for some years educated by a distant relation, a Clergyman. While she was with him a young gentleman, son to a man of property in the neighbourhood, took particular notice of her. It is true, he never talked of love; but then they played and sung in concert; drew landscapes together, and while she worked he read to her, cultivated her taste, and stole imperceptibly her heart. Just at this juncture, when smiling, unanalyzed hope made every prospect bright, and gay expectation danced in her eyes, her benefactor died. She returned to her mother — the companion of her youth forgot her, they took no more sweet counsel together. This disappointment spread a sadness over her countenance, and made it interesting. She grew fond of solitude, and her character appeared similar to Mary’s, though her natural disposition was very different.

She was several years older than Mary, yet her refinement, her taste, caught her eye, and she eagerly sought her friendship: before her return she had assisted the family, which was almost reduced to the last ebb; and now she had another motive to actuate her.

As she had often occasion to send messages to Ann, her new friend, mistakes were frequently made; Ann proposed that in future they should be written ones, to obviate this difficulty, and render their intercourse more agreeable. Young people are mostly fond of scribbling; Mary had had very little instruction; but by copying her friend’s letters, whose hand she admired, she soon became a proficient; a little practice made her write with tolerable correctness, and her genius gave force to it. In conversation, and in writing, when she felt, she was pathetic, tender and persuasive; and she expressed contempt with such energy, that few could stand the flash of her eyes.

As she grew more intimate with Ann, her manners were softened, and she acquired a degree of equality in her behaviour: yet still her spirits were fluctuating, and her movements rapid. She felt less pain on account of her mother’s partiality to her brother, as she hoped now to experience the pleasure of being beloved; but this hope led her into new sorrows, and, as usual, paved the way for disappointment. Ann only felt gratitude; her heart was entirely engrossed by one object, and friendship could not serve as a substitute; memory officiously retraced past scenes, and unavailing wishes made time loiter.

Mary was often hurt by the involuntary indifference which these consequences produced. When her friend was all the world to her, she found she was not as necessary to her happiness; and her delicate mind could not bear to obtrude her affection, or receive love as an alms, the offspring of pity. Very frequently has she ran to her with delight, and not perceiving any thing of the same kind in Ann’s countenance, she has shrunk back; and, falling from one extreme into the other, instead of a warm greeting that was just slipping from her tongue, her expressions seemed to be dictated by the most chilling insensibility.

She would then imagine that she looked sickly or unhappy, and then all her tenderness would return like a torrent, and bear away all reflection. In this manner was her sensibility called forth, and exercised, by her mother’s illness, her friend’s misfortunes, and her own unsettled mind.

CHAP. IV.

Near to her father’s house was a range of mountains; some of them were, literally speaking, cloud-capt, for on them clouds continually rested, and gave grandeur to the prospect; and down many of their sides the little bubbling cascades ran till they swelled a beautiful river. Through the straggling trees and bushes the wind whistled, and on them the birds sung, particularly the robins; they also found shelter in the ivy of an old castle, a haunted one, as the story went; it was situated on the brow of one of the mountains, and commanded a view of the sea. This castle had been inhabited by some of her ancestors; and many tales had the old house-keeper told her of the worthies who had resided there.

When her mother frowned, and her friend looked cool, she would steal to this retirement, where human foot seldom trod — gaze on the sea, observe the grey clouds, or listen to the wind which struggled to free itself from the only thing that impeded its course. When more cheerful, she admired the various dispositions of light and shade, the beautiful tints the gleams of sunshine gave to the distant hills; then she rejoiced in existence, and darted into futurity.

One way home was through the cavity of a rock covered with a thin layer of earth, just sufficient to afford nourishment to a few stunted shrubs and wild plants, which grew on its sides, and nodded over the summit. A clear stream broke out of it, and ran amongst the pieces of rocks fallen into it. Here twilight always reigned — it seemed the Temple of Solitude; yet, paradoxical as the assertion may appear, when the foot sounded on the rock, it terrified the intruder, and inspired a strange feeling, as if the rightful sovereign was dislodged. In this retreat she read Thomson’s Seasons, Young’s Night-Thoughts, and Paradise Lost.

At a little distance from it were the huts of a few poor fishermen, who supported their numerous children by their precarious labour. In these little huts she frequently rested, and denied herself every childish gratification, in order to relieve the necessities of the inhabitants. Her heart yearned for them, and would dance with joy when she had relieved their wants, or afforded them pleasure.

In these pursuits she learned the luxury of doing good; and the sweet tears of benevolence frequently moistened her eyes, and gave them a sparkle which, exclusive of that, they had not; on the contrary, they were rather fixed, and would never have been observed if her soul had not animated them. They were not at all like those brilliant ones which look like polished diamonds, and dart from every superfice, giving more light to the beholders than they receive themselves.

Her benevolence, indeed, knew no bounds; the distress of others carried her out of herself; and she rested not till she had relieved or comforted them. The warmth of her compassion often made her so diligent, that many things occurred to her, which might have escaped a less interested observer.

In like manner, she entered with such spirit into whatever she read, and the emotions thereby raised were so strong, that it soon became a part of her mind.

Enthusiastic sentiments of devotion at this period actuated her; her Creator was almost apparent to her senses in his works; but they were mostly the grand or solemn features of Nature which she delighted to contemplate. She would stand and behold the waves rolling, and think of the voice that could still the tumultuous deep.

These propensities gave the colour to her mind, before the passions began to exercise their tyrannic sway, and particularly pointed out those which the soil would have a tendency to nurse.

Years after, when wandering through the same scenes, her imagination has strayed back, to trace the first placid sentiments they inspired, and she would earnestly desire to regain the same peaceful tranquillity.

Many nights she sat up, if I may be allowed the expression, conversing with the Author of Nature, making verses, and singing hymns of her own composing. She considered also, and tried to discern what end her various faculties were destined to pursue; and had a glimpse of a truth, which afterwards more fully unfolded itself.

She thought that only an infinite being could fill the human soul, and that when other objects were followed as a means of happiness, the delusion led to misery, the consequence of disappointment. Under the influence of ardent affections, how often has she forgot this conviction, and as often returned to it again, when it struck her with redoubled force. Often did she taste unmixed delight; her joys, her ecstacies arose from genius.

She was now fifteen, and she wished to receive the holy sacrament; and perusing the scriptures, and discussing some points of doctrine which puzzled her, she would sit up half the night, her favourite time for employing her mind; she too plainly perceived that she saw through a glass darkly; and that the bounds set to stop our intellectual researches, is one of the trials of a probationary state.

But her affections were roused by the display of divine mercy; and she eagerly desired to commemorate the dying love of her great benefactor. The night before the important day, when she was to take on herself her baptismal vow, she could not go to bed; the sun broke in on her meditations, and found her not exhausted by her watching.

The orient pearls were strewed around — she hailed the morn, and sung with wild delight, Glory to God on high, good will towards men. She was indeed so much affected when she joined in the prayer for her eternal preservation, that she could hardly conceal her violent emotions; and the recollection never failed to wake her dormant piety when earthly passions made it grow languid.

These various movements of her mind were not commented on, nor were the luxuriant shoots restrained by culture. The servants and the poor adored her.

In order to be enabled to gratify herself in the highest degree, she practiced the most rigid œconomy, and had such power over her appetites and whims, that without any great effort she conquered them so entirely, that when her understanding or affections had an object, she almost forgot she had a body which required nourishment.

This habit of thinking, this kind of absorption, gave strength to the passions.

We will now enter on the more active field of life.

CHAP. V.

A few months after Mary was turned of seventeen, her brother was attacked by a violent fever, and died before his father could reach the school.

She was now an heiress, and her mother began to think her of consequence, and did not call her the child. Proper masters were sent for; she was taught to dance, and an extraordinary master procured to perfect her in that most necessary of all accomplishments.

A part of the estate she was to inherit had been litigated, and the heir of the person who still carried on a Chancery suit, was only two years younger than our heroine. The fathers, spite of the dispute, frequently met, and, in order to settle it amicably, they one day, over a bottle, determined to quash it by a marriage, and, by uniting the two estates, to preclude all farther enquiries into the merits of their different claims.

While this important matter was settling, Mary was otherwise employed. Ann’s mother’s resources were failing; and the ghastly phantom, poverty, made hasty strides to catch them in his clutches. Ann had not fortitude enough to brave such accumulated misery; besides, the canker-worm was lodged in her heart, and preyed on her health. She denied herself every little comfort; things that would be no sacrifice when a person is well, are absolutely necessary to alleviate bodily pain, and support the animal functions.

There were many elegant amusements, that she had acquired a relish for, which might have taken her mind off from its most destructive bent; but these her indigence would not allow her to enjoy: forced then, by way of relaxation, to play the tunes her lover admired, and handle the pencil he taught her to hold, no wonder his image floated on her imagination, and that taste invigorated love.

Poverty, and all its inelegant attendants, were in her mother’s abode; and she, though a good sort of a woman, was not calculated to banish, by her trivial, uninteresting chat, the delirium in which her daughter was lost.

This ill-fated love had given a bewitching softness to her manners, a delicacy so truly feminine, that a man of any feeling could not behold her without wishing to chase her sorrows away. She was timid and irresolute, and rather fond of dissipation; grief only had power to make her reflect.

In every thing it was not the great, but the beautiful, or the pretty, that caught her attention. And in composition, the polish of style, and harmony of numbers, interested her much more than the flights of genius, or abstracted speculations.

She often wondered at the books Mary chose, who, though she had a lively imagination, would frequently study authors whose works were addressed to the understanding. This liking taught her to arrange her thoughts, and argue with herself, even when under the influence of the most violent passions.

Ann’s misfortunes and ill health were strong ties to bind Mary to her; she wished so continually to have a home to receive her in, that it drove every other desire out of her mind; and, dwelling on the tender schemes which compassion and friendship dictated, she longed most ardently to put them in practice.

Fondly as she loved her friend, she did not forget her mother, whose decline was so imperceptible, that they were not aware of her approaching dissolution. The physician, however, observing the most alarming symptoms; her husband was apprised of her immediate danger; and then first mentioned to her his designs with respect to his daughter.

She approved of them; Mary was sent for; she was not at home; she had rambled to visit Ann, and found her in an hysteric fit. The landlord of her little farm had sent his agent for the rent, which had long been due to him; and he threatened to seize the stock that still remained, and turn them out, if they did not very shortly discharge the arrears.

As this man made a private fortune by harassing the tenants of the person to whom he was deputy, little was to be expected from his forbearance.

All this was told to Mary — and the mother added, she had many other creditors who would, in all probability, take the alarm, and snatch from them all that had been saved out of the wreck. “I could bear all,” she cried; “but what will become of my children? Of this child,” pointing to the fainting Ann, “whose constitution is already undermined by care and grief — where will she go?” — Mary’s heart ceased to beat while she asked the question — She attempted to speak; but the inarticulate sounds died away. Before she had recovered herself, her father called himself to enquire for her; and desired her instantly to accompany him home.

Engrossed by the scene of misery she had been witness to, she walked silently by his side, when he roused her out of her reverie by telling her that in all likelihood her mother had not many hours to live; and before she could return him any answer, informed her that they had both determined to marry her to Charles, his friend’s son; he added, the ceremony was to be performed directly, that her mother might be witness of it; for such a desire she had expressed with childish eagerness.

Overwhelmed by this intelligence, Mary rolled her eyes about, then, with a vacant stare, fixed them on her father’s face; but they were no longer a sense; they conveyed no ideas to the brain. As she drew near the house, her wonted presence presence of mind returned: after this suspension of thought, a thousand darted into her mind, — her dying mother, — her friend’s miserable situation, — and an extreme horror at taking — at being forced to take, such a hasty step; but she did not feel the disgust, the reluctance, which arises from a prior attachment.

She loved Ann better than any one in the world — to snatch her from the very jaws of destruction — she would have encountered a lion. To have this friend constantly with her; to make her mind easy with respect to her family, would it not be superlative bliss?

Full of these thoughts she entered her mother’s chamber, but they then fled at the sight of a dying parent. She went to her, took her hand; it feebly pressed her’s. “My child,” said the languid mother: the words reached her heart; she had seldom heard them pronounced with accents denoting affection; “My child, I have not always treated you with kindness — God forgive me! do you?” — Mary’s tears strayed in a disregarded stream; on her bosom the big drops fell, but did not relieve the fluttering tenant. “I forgive you!” said she, in a tone of astonishment.

The clergyman came in to read the service for the sick, and afterwards the marriage ceremony was performed. Mary stood like a statue of Despair, and pronounced the awful vow without thinking of it; and then ran to support her mother, who expired the same night in her arms.

Her husband set off for the continent the same day, with a tutor, to finish his studies at one of the foreign universities.

Ann was sent for to console her, not on account of the departure of her new relation, a boy she seldom took any notice of, but to reconcile her to her fate; besides, it was necessary she should have a female companion, and there was not any maiden aunt in the family, or cousin of the same class.

CHAP. VI.

Mary was allowed to pay the rent which gave her so much uneasiness, and she exerted every nerve to prevail on her father effectually to succour the family; but the utmost she could obtain was a small sum very inadequate to the purpose, to enable the poor woman to carry into execution a little scheme of industry near the metropolis.

Her intention of leaving that part of the country, had much more weight with him, than Mary’s arguments, drawn from motives of philanthropy and friendship; this was a language he did not understand; expressive of occult qualities he never thought of, as they could not be seen or felt.

After the departure of her mother, Ann still continued to languish, though she had a nurse who was entirely engrossed by the desire of amusing her. Had her health been re-established, the time would have passed in a tranquil, improving manner.

During the year of mourning they lived in retirement; music, drawing, and reading, filled up the time; and Mary’s taste and judgment were both improved by contracting a habit of observation, and permitting the simple beauties of Nature to occupy her thoughts.

She had a wonderful quickness in discerning distinctions and combining ideas, that at the first glance did not appear to be similar. But these various pursuits did not banish all her cares, or carry off all her constitutional black bile. Before she enjoyed Ann’s society, she imagined it would have made her completely happy: she was disappointed, and yet knew not what to complain of.

As her friend could not accompany her in her walks, and wished to be alone, for a very obvious reason, she would return to her old haunts, retrace her anticipated pleasures — and wonder how they changed their colour in possession, and proved so futile.

She had not yet found the companion she looked for. Ann and she were not congenial minds, nor did she contribute to her comfort in the degree she expected. She shielded her from poverty; but this was only a negative blessing; when under the pressure it was very grievous, and still more so were the apprehensions; but when when exempt from them, she was not contented.

Such is human nature, its laws were not to be inverted to gratify our heroine, and stop the progress of her understanding, happiness only flourished in paradise — we cannot taste and live.

Another year passed away with increasing apprehensions. Ann had a hectic cough, and many unfavourable prognostics: Mary then forgot every thing but the fear of losing her, and even imagined that her recovery would have made her happy.

Her anxiety led her to study physic, and for some time she only read books of that cast; and this knowledge, literally speaking, ended in vanity and vexation of spirit, as it enabled her to foresee what she could not prevent.

As her mind expanded, her marriage appeared appeared a dreadful misfortune; she was sometimes reminded of the heavy yoke, and bitter was the recollection!

In one thing there seemed to be a sympathy between them, for she wrote formal answers to his as formal letters. An extreme dislike took root in her mind; the found of his name made her turn sick; but she forgot all, listening to Ann’s cough, and supporting her languid frame. She would then catch her to her bosom with convulsive eagerness, as if to save her from sinking into an opening grave.

CHAP. VII.

It was the will of Providence that Mary should experience almost every species of sorrow. Her father was thrown from his horse, when his blood was in a very inflammatory state, and the bruises were very dangerous; his recovery was not expected by the physical tribe.

Terrified at seeing him so near death, and yet so ill prepared for it, his daughter sat by his bed, oppressed by the keenest anguish, which her piety increased.

Her grief had nothing selfish in it; he was not a friend or protector; but he was her father, an unhappy wretch, going into eternity, depraved and thoughtless. Could a life of sensuality be a preparation for a peaceful death? Thus meditating, she passed the still midnight hour by his bedside.

The nurse fell asleep, nor did a violent thunder storm interrupt her repose, though it made the night appear still more terrific to Mary. Her father’s unequal breathing alarmed her, when she heard a long drawn breath, she feared it was his last, and watching for another, a dreadful peal of thunder struck her ears. Considering the separation of the soul and body, this night seemed sadly solemn, and the hours long.

Death is indeed a king of terrors when he attacks the vicious man! The compassionate heart finds not any comfort; but dreads an eternal separation. No transporting greetings are anticipated, when the survivors also shall have finished their their course; but all is black! — the grave may truly be said to receive the departed — this is the sting of death!

Night after night Mary watched, and this excessive fatigue impaired her own health, but had a worse effect on Ann; though she constantly went to bed, she could not rest; a number of uneasy thoughts obtruded themselves; and apprehensions about Mary, whom she loved as well as her exhausted heart could love, harassed her mind. After a sleepless, feverish night she had a violent fit of coughing, and burst a blood-vessel. The physician, who was in the house, was sent for, and when he left the patient, Mary, with an authoritative voice, insisted on knowing his real opinion. Reluctantly he gave it, that her friend was in a critical state; and if she passed the approaching winter in England, he imagined she would die in the spring; a season fatal to consumptive disorders. The spring! — Her husband was then expected. — Gracious Heaven, could she bear all this.

In a few days her father breathed his last. The horrid sensations his death occasioned were too poignant to be durable: and Ann’s danger, and her own situation, made Mary deliberate what mode of conduct she should pursue. She feared this event might hasten the return of her husband, and prevent her putting into execution a plan she had determined on. It was to accompany Ann to a more salubrious climate.

CHAP. VIII.

I mentioned before, that Mary had never had any particular attachment, to give rise to the disgust that daily gained ground. Her friendship for Ann occupied her heart, and resembled a passion. She had had, indeed, several transient likings; but they did not amount to love. The society of men of genius delighted her, and improved her faculties. With beings of this class she did not often meet; it is a rare genus; her first favourites were men past the meridian of life, and of a philosophic turn.

Determined on going to the South of France, or Lisbon; she wrote to the man she had promised to obey. The physicians had said change of air was necessary for her as well as her friend. She mentioned this, and added, “Her comfort, almost her existence, depended on the recovery of the invalid she wished to attend; and that should she neglect to follow the medical advice she had received, she should never forgive herself, or those who endeavoured to prevent her.” Full of her design, she wrote with more than usual freedom; and this letter was like most of her others, a transcript of her heart.

“This dear friend,” she exclaimed, “I love for her agreeable qualities, and substantial virtues. Continual attention to her health, and the tender office of a nurse, have created an affection very like a maternal one — I am her only support, she leans on me — could I forsake the forsaken, and break the bruised reed — No — I would die first! I must — I will go.”

She would have added, “you would very much oblige me by consenting;” but her heart revolted — and irresolutely she wrote something about wishing him happy.— “Do I not wish all the world well?” she cried, as she subscribed her name — It was blotted, the letter sealed in a hurry, and sent out of her sight; and she began to prepare for her journey.

By the return of the post she received an answer; it contained some common-place remarks on her romantic friendship, as he termed it; “But as the physicians advised change of air, he had no objection.”

CHAP. IX.

There was nothing now to retard their journey; and Mary chose Lisbon rather than France, on account of its being further removed from the only person she wished not to see.

They set off accordingly for Falmouth, in their way to that city. The journey was of use to Ann, and Mary’s spirits were raised by her recovered looks — She had been in despair — now she gave way to hope, and was intoxicated with it. On ship-board Ann always remained in the cabin; the sight of the water terrified her: on the contrary, Mary, after she was gone to bed, or when she fell asleep in the day, went on deck, conversed with the sailors, and surveyed the boundless expanse before her with delight. One instant she would regard the ocean, the next the beings who braved its fury. Their insensibility and want of fear, she could not name courage; their thoughtless mirth was quite of an animal kind, and their feelings as impetuous and uncertain as the element they plowed.

They had only been a week at sea when they hailed the rock of Lisbon, and the next morning anchored at the castle. After the customary visits, they were permitted to go on shore, about three miles from the city; and while one of the crew, who understood the language, went to procure them one of the ugly carriages peculiar to the country, they waited in the Irish convent, which is situated close to the Tagus.

Some of the people offered to conduct them into the church, where there was a fine organ playing; Mary followed them, but Ann preferred staying with a nun she had entered into conversation with.

One of the nuns, who had a sweet voice, was singing; Mary was struck with awe; her heart joined in the devotion; and tears of gratitude and tenderness flowed from her eyes. My Father, I thank thee! burst from her — words were inadequate to express her feelings. Silently, she surveyed the lofty dome; heard unaccustomed sounds; and saw faces, strange ones, that she could not yet greet with fraternal love.

In an unknown land, she considered that the Being she adored inhabited eternity, was ever present in unnumbered worlds. When she had not any one she loved near her, she was particularly sensible of the presence of her Almighty Friend.

The arrival of the carriage put a stop to her speculations; it was to conduct them to an hotel, fitted up for the reception of invalids. Unfortunately, before they could reach it there was a violent shower of rain; and as the wind was very high, it beat against the leather curtains, which they drew along the front of the vehicle, to shelter themselves from it; but it availed not, some of the rain forced its way, and Ann felt the effects of it, for she caught cold, spite of Mary’s precautions.

As is the custom, the rest of the invalids, or lodgers, sent to enquire after their health; and as soon as Ann left her chamber, in which her complaints seldom confined her the whole day, they came in person to pay their compliments. Three fashionable females, and two gentlemen; the one a brother of the eldest of the young ladies, and the other an invalid, who came, like themselves, for the benefit of the air. They entered into conversation immediately.

People who meet in a strange country, and are all together in a house, soon get acquainted, without the formalities which attend visiting in separate houses, where they are surrounded by domestic friends. Ann was particularly delighted at meeting with agreeable society; a little hectic fever generally made her low-spirited in the morning, and lively in the evening, when she wished for company. Mary, who only thought of her, determined to cultivate their acquaintance, as she knew, that if her mind could be diverted, her body might gain strength.

They were all musical, and proposed having little concerts. One of the gentlemen played on the violin, and the other on the german-flute. The instruments were brought in, with all the eagerness that attends putting a new scheme in execution.

Mary had not said much, for she was diffident; she seldom joined in general conversations; though her quickness of penetration enabled her soon to enter into the characters of those she conversed with; and her sensibility made her desirous of pleasing every human creature. Besides, if her mind was not occupied by any particular sorrow, or study, she caught reflected pleasure, and was glad to see others happy, though their mirth did not interest her.

This day she was continually thinking of Ann’s recovery, and encouraging the cheerful hopes, which though they dissipated the spirits that had been condensed by melancholy, yet made her wish to be silent. The music, more than the conversation, disturbed her reflections; but not at first. The gentleman who played on the german-flute, was a handsome, well-bred, sensible man; and his observations, if not original, were pertinent.

The other, who had not said much, began to touch the violin, and played a little Scotch ballad; he brought such a thrilling sound out of the instrument, that Mary started, and looking at him with more attention than she had done before, and saw, in a face rather ugly, strong lines of genius. His manners were awkward, that kind of awkwardness which is often found in literary men: he seemed a thinker, and delivered his opinions in elegant expressions, and musical tones of voice.

When the concert was over, they all retired to their apartments. Mary always slept with Ann, as she was subject to terrifying dreams; and frequently in the night was obliged to be supported, to avoid suffocation. They chatted about their new acquaintance in their own apartment, and, with respect to the gentlemen, differed in opinion.

CHAP. X.

Every day almost they saw their new acquaintance; and civility produced intimacy. Mary sometimes left her friend with them; while she indulged herself in viewing new modes of life, and searching out the causes which produced them. She had a metaphysical turn, which inclined her to reflect on every object that passed by her; and her mind was not like a mirror, which receives every floating image, but does not retain them: she had not any prejudices, for every opinion was examined before it was adopted.

The Roman Catholic ceremonies attracted her attention, and gave rise to conversations when they all met; and one of the gentlemen continually introduced deistical notions, when he ridiculed the pageantry they all were surprised at observing. Mary thought of both the subjects, the Romish tenets, and the deistical doubts; and though not a sceptic, thought it right to examine the evidence on which her faith was built. She read Butler’s Analogy, and some other authors: and these researches made her a christian from conviction, and she learned charity, particularly with respect to sectaries; saw that apparently good and solid arguments might take their rise from different points of view; and she rejoiced to find that those she should not concur with had some reason on their side.

CHAP. XI.

When I mentioned the three ladies, I said they were fashionable women; and it was all the praise, as a faithful historian, I could bestow on them; the only thing in which they were consistent. I forgot to mention that they were all of one family, a mother, her daughter, and niece. The daughter was sent by her physician, to avoid a northerly winter; the mother, her niece, and nephew, accompanied her.

They were people of rank; but unfortunately, though of an ancient family, the title had descended to a very remote branch — a branch they took care to be intimate with; and servilely copied the Countess’s airs. Their minds were shackled with a set of notions concerning propriety, the fitness of things for the world’s eye, trammels which always hamper weak people. What will the world say? was the first thing that was thought of, when they intended doing any thing they had not done before. Or what would the Countess do on such an occasion? And when this question was answered, the right or wrong was discovered without the trouble of their having any idea of the matter in their own heads. This same Countess was a fine planet, and the satellites observed a most harmonic dance around her.

After this account it is scarcely necessary to add, that their minds had received very little cultivation. They were taught French, Italian, and Spanish; English was their vulgar tongue. And what did they learn? Hamlet will tell you — words — words. But let me not forget that they squalled Italian songs in the true gusto. Without having any seeds sown in their understanding, or the affections of the heart set to work, they were brought out of their nursery, or the place they were secluded in, to prevent their faces being common; like blazing stars, to captivate Lords.

They were pretty, and hurrying from one party of pleasure to another, occasioned the disorder which required change of air. The mother, if we except her being near twenty years older, was just the same creature; and these additional years only served to make her more tenaciously adhere to her habits of folly, and decide with stupid gravity, some trivial points of ceremony, as a matter of the last importance; of which she was a competent judge, from having lived in the fashionable world so long: that world to which the ignorant look up as we do to the sun.

It appears to me that every creature has some notion — or rather relish, of the sublime. Riches, and the consequent state, are the sublime of weak minds: — These images fill, nay, are too big for their narrow souls.

One afternoon, which they had engaged to spend together, Ann was so ill, that Mary was obliged to send an apology for not attending the tea-table. The apology brought them on the carpet; and the mother, with a look of solemn importance, turned to the sick man, whose name was Henry, and said;

“Though people of the first fashion are frequently at places of this kind, intimate with they know not who; yet I do not choose that my daughter, whose family is so respectable, should be intimate with any one she would blush to know elsewhere. It is only on that account, for I never suffer her to be with any one but in my company,” added she, sitting more erect; and a smile of self-complacency dressed her countenance.

“I have enquired concerning these strangers, and find that the one who has the most dignity in her manners, is really a woman of fortune.” “Lord, mamma, how ill she dresses:” mamma went on; “She is a romantic creature, you must not copy her, miss; yet she is an heiress of the large fortune in —— shire, of which you may remember to have heard the Countess speak the night you had on the dancing-dress that was so much admired; but she is married.”

She then told them the whole story as she heard it from her maid, who picked it out of Mary’s servant. “She is a foolish creature, and this friend that she pays as much attention to as if she was a lady of quality, is a beggar.” “Well, how strange!” cried the girls.

“She is, however, a charming creature,” said her nephew. Henry sighed, and strode across the room once or twice; then took up his violin, and played the air which first struck Mary; he had often heard her praise it.