8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

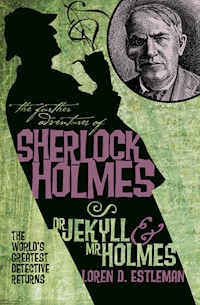

When Sir Danvers Carew is brutally murdered, the Queen herself calls on Sherlock Holmes to investigate. In the course of his enquiries, the esteemed detective is struck by the strange link between the highly respectable Dr Henry Jekyll and the immoral Edward Hyde. Can he work out what it is that connects the two men or is it mystery even beyond the skills of the great Sherlock Holmes?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

AVAILABLE NOW FROM TITAN BOOKS:

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES SERIES

THE ECTOPLASMIC MAN

Daniel Stashower

THE SCROLL OF THE DEAD

David Stuart Davies

THE STALWART COMPANIONS

H. Paul Jeffers

THE VEILED DETECTIVE

David Stuart Davies

THE WAR OF THE WORLDS

Manley Wade Wellman & Wade Wellman

THE MAN FROM HELL

Barrie Roberts

THE SEVENTH BULLET

Daniel D. Victor

THE WHITECHAPEL HORRORS

Edward B. Hanna

COMING SOON FROM TITAN BOOKS:

THE GIANT RAT OF SUMATRA

Richard L. Boyer

THE ANGEL OF THE OPERA

Sam Siciliano

The further adventures of

SHERLOCK HOLMES

DR. JEKYLL AND MR. HOLMES

LOREN D. ESTLEMAN

TITAN BOOKS

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES:

DR. JEKYLL AND MR. HOLMES

ePub ISBN: 9781848569201

Published by

Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark St

London

SE1 0UP

First edition: October 2010

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© 1979, 2010 Loren D. Estleman

Visit our website:

www.titanbooks.com

What did you think of this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at: [email protected], or write to us at the above address. To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive Titan offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website: www.titanbooks.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound in the USA.

To Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Robert Louis Stevenson

– one thrill in return for many

“When a doctor goes wrong, he is the first of criminals.”

– Sherlock Holmes, as quoted in

“The Adventure of the Speckled Band”

Contents

Foreword

Preface

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Acknowledgements

Dr. Jekyll’s “Case Of Identity”: A Word After By Loren D. Estleman

Also Available

Foreword

“You the guy that did the book about Sherlock Holmes?”

Ordinarily I make it a point to answer that kind of query with an appropriate wisecrack, but there was something about this particular visitor that warned me to keep a leash on my devastating wit. He had emerged from the back seat of a black limousine nearly as long as my driveway, flanked by a pair of healthy-looking young men with jaws like pigs’ knuckles and odd bulges beneath the armpits of their tailor-made suits. The fellow in the middle was short and built like a bouncer and had thick black hair in which the marks of his comb glistened beneath the illumination of my porch light. His face was evenly tanned, cleanshaven, and dominated by a pair of solid black wraparound sunglasses, although the sun had long since descended. He looked forty but turned out later to be closer to sixty. When he spoke, he had a Brooklyn accent that dared me to sneer at it. I didn’t.

“I edited The Adventure of the Sanguinary Count, if that’s what you mean,” said I. I was determined in spite of his formidable appearance to remain master of the situation. His visit had interrupted my writing and I was anxious to get back to it.

Without turning his head he held out a hand to the young man at his right, who immediately placed in it a package wrapped in brown paper, which he then thrust into my hands.

“Read it,” he ordered.

I opened my mouth to protest, but the eyes of his companions grew cold suddenly, and instead I stepped aside from the door to admit the trio. Once inside, the man in the middle took possession of my favorite easy chair while the others took up standing positions on either side of it, quiet and solid as andirons. I glanced longingly toward the telephone, but my chances of reaching it and dialing for help before one of them showed me what the lumps were in their jackets and pumped me full of lead were less than encouraging, and in any case if this was a robbery or a kidnapping, it was being handled in such a bizarre manner that as a writer I thought it might be worth my while to see it through. All three watched as I sat down on the sofa opposite them and opened the package.

I had all I could do to refrain from groaning when I read the title. Since the publication of Sherlock Holmes vs. Dracula: Or the Adventure of the Sanguinary Count, of which I was the editor, I had become the recipient of no fewer than three “genuine” Watsonian manuscripts sent to me from scattered corners of the world. I had not required an expert to tell me that none of them was worth the paper it had been forged upon. Nor had I use for another. Faced, however, with a most persuasive argument in the persons of the three strapping fellows in my living room, I read on.

A fresh glance at the handwriting caused my pulse to quicken. I had spent too much time decoding Watson’s earlier manuscript not to recognize his careless scrawl when I encountered it again. It was written on ancient vellum, with many corrections in the margins — signs of the Victorian perfectionist which were usually lost when A. Conan Doyle, his friend and literary agent, copied out his works for publication. I was immediately convinced of its authenticity. Quite forgetting my “guests,” I continued reading and finished the manuscript in that one sitting. When I set it aside some three hours later I was burning with curiosity, but I managed to appear casual as I asked the fellow in the dark glasses how the artifact had come into his possession. The story he told bears repeating.

In 1943, while serving a five-year penitentiary sentence for armed robbery, my visitor, who gave his name as Georgie Collins (a pseudonym; I was better off, he said, not knowing his real identity), was approached by the U.S. Army and offered the chance to shorten his term if he joined the service. He accepted, and a year later found himself in France during the post-D-Day Allied offensive.

One day he and a small patrol stormed a bombed-out chateau near Toulouse, “blew away” a nest of Germans hidden inside, and set to work searching the rubble for much-needed supplies. In a space between two walls Collins spotted a tattered sheaf of papers, covered with dust and bound with a faded black ribbon. After reading only a few lines he saw the discovery for what it was and, making sure that none of his colleagues was observing him, tucked the manuscript away inside his rucksack.

Surreptitiously questioning the locals, Collins learned that the chateau had been used for medical research by Doctor, later Sir, John H. Watson when he served as a civilian attached to the British Army during the First World War. The area had been heavily shelled even then; it seemed likely that during one of these bombardments the manuscript had been dislodged from the top of a table or bureau and had fallen through a hole in the wall and been left behind in the confusion of the final days of the war.

History repeated itself. Shortly after his return to the States, Georgie Collins married his childhood sweetheart and tossed the rucksack containing the manuscript into a utility closet in his home, where it lay forgotten among his other war mementos for more than three decades. If not for the popularity of the other lost work which I had edited, he said, it might still be there.

When I asked him why he had come to me, Collins smiled for the first time. He had very white teeth, very even — the work, no doubt, of an expensive cosmetic dentist.

“I got a sudden need for cash,” he said. “When I heard about this here Sherlock Holmes book you did, I remembered that thing I found in France and figured you might be willing to do whatever it is you do with these things and split the take with me. I don’t know nothing about editing. The only editor I ever knew got blew up in his car when he tried to publish a piece about an acquaintance of mine.”

I explained to him that profits are a long time coming in the publishing business and asked if he was prepared to wait several months for his share. The smile fled from his features.

“I ain’t got that kind of time. How much can you give me right now, tonight?”

“How much do you want?”

The figure he quoted had too many zeros. I countered with one of my own. His frown grew dangerous. Sensing his displeasure, the men beside his chair perked up like dogs anticipating the signal to attack.

“Chicken feed,” he snarled.

I summoned up my courage and shrugged. “It’s most of what I own. I need something to live on. You can consider it a down payment.”

He scratched his chin noisily. “All right, I’ll take it. In cash.”

“I don’t have that much on hand. Will you take a check?” I reached for my checkbook.

“I only deal in cash.”

“I’ll have to go to the bank, and it won’t be open again until Monday.”

He fidgeted in his chair, made faces. Finally: “Okay, I’ll take the check. Make it out to cash.”

I did so, and handed it to him. “It’s good,” I said as he studied it closely.

“I believe you.” He folded the check and put it away inside his coat. “You don’t look that dumb.”

My writer’s curiosity got the better of me and I asked him why he needed the money in such a hurry. To my surprise, he seemed unruffled by the question.

“Travel expenses. Some people are looking for me, and some others don’t want me found. So I’m taking a vacation. Every cent I got is tied up in the — in my business.” He got up and stood looking down at me. The lamplight glinted off the opaque lenses of his glasses. “Do a good job with it. You’ll be hearing from me again soon.”

He turned upon his heel and left, but not before one of the young men, slipping his hand inside his jacket, leaned out through the doorway, glanced to right and left, then straightened and nodded to his chief. The three went out together. A moment later I heard the engine of the limousine purr into life, then a crunch of gravel as it swept into the road and was gone. By that time I had already snatched up a pencil and set to work.

The prospect of editing this manuscript presented much the same difficulties as I had experienced with the first. I have established that Watson’s handwriting was abominable; worse, the existence of a surprising number of redundancies and mixed metaphors made it abundantly clear that this was a first draft and that much revising was necessary before it could be allowed to go to the typesetters — revising which, possibly because of the war and the subsequent misplacing of the manuscript, Watson was unable to accomplish. I have, therefore, taken it upon myself to provide those corrections which I am certain the good doctor would have supplied had not time and circumstances been working against him. I am prepared to take the consequences for this literary blasphemy, with the understanding that wherever possible I have left Watson’s prose untouched, and that where this was not possible I have endeavored to keep to his distinctive style. The book, then, is ninety per cent original.

The narrative provides two significant revelations which may or may not clear up a number of outstanding arguments among Sherlockians, depending upon how they are received. First, the appearance of Sherlock Holmes’s brother Mycroft in 1885 would indicate that Watson, writing of his first meeting with the elder Holmes in “The Greek Interpreter,” was guilty of literary license. Since this initial encounter would of necessity predate the events contained herein, it was impossible for Mycroft to have said, upon being introduced, “I hear of Sherlock everywhere since you became his chronicler.” As every student knows, the first of these chronicles, A Study in Scarlet, did not appear until December of 1887, more than two years after the events described in the present account. If Mycroft did indeed make that statement, he would have had to have done so on some later occasion. This is not so difficult to accept, as Watson was sometimes known to telescope conversations made on different occasions into one in order to make his account more complete. A case in point: Watson asserts, in “The Final Problem,” that he has “never” heard of the evil Professor Moriarty when in fact, as we are shown in The Valley of Fear, which predates that account, he is already fairly well informed upon the subject. Since “Problem” appeared first, the good doctor obviously chose to include Holmes’s introductory description of the wicked scholar from some earlier occasion in order not to confuse his readers, who were unaware of the professor’s existence. This same reasoning may account for Mycroft’s opening lines in “The Greek Interpreter,” a case which we now see had to have taken place prior to January of 1885.

Second, we are at last made aware of Watson’s alma mater, the University of Edinburgh, where he studied medicine before taking his degree at the University of London in 1878. The subject has long been a controversial one among erudite Sherlockians, who, knowing that the London facility of Watson’s day was not a teaching institution but merely a clearinghouse of diplomas, have spent many hours arguing over where Holmes’s Boswell attended classes. Perhaps it is there that he met Conan Doyle prior to the latter’s graduation from the same university in 1881 and sowed the seeds for the working relationship which was to make the name of Sherlock Holmes synonymous with the art of detection.

The following, with some slight interference of my own, is a chronicle in Watson’s own words of the period between October 1883 and March 1885 — hitherto a Sherlockian mystery — and of those events connected with the bizarre relationship of Henry Jekyll to Edward Hyde as viewed from a fresh angle. Whether or not, as in the case of their brush with Count Dracula in 1890, the part played by Holmes and Watson had any effect upon its outcome will likely remain a point of debate among scholars for some time to come. In my opinion it was the Baker Street sleuth’s bloodhound tenacity which forced Mr. Hyde to live up to his name.

As for Georgie Collins, I was to hear of him again sooner than either of us expected. Two days after our parting I read in the newspaper of the death of a reputed underworld chief who had been gunned down that morning along with his two bodyguards at Detroit Metropolitan Airport. He had been sought by a grand jury investigating the mysterious disappearance of a famed labor leader, and it was believed that he had been silenced by his gangland cronies. Found upon his person was a one-way ticket to Mexico and a substantial amount of cash worn in a money belt. A photograph identified as one taken of the victim two years before, during his trial for income tax evasion, showed my visitor of the other night handcuffed between two gray-looking federal agents. Although the name beneath the picture was different, there was no mistaking the hard white smile he was flashing. Only the sunglasses were missing.

Whatever his sins, and however base his motives, Georgie Collins is responsible for the present volume’s existence; because of this, his place among the great literary patrons of history is assured. I will therefore take the risk of official disapproval by dedicating this Foreword to his memory.

Loren D. Estleman

Dexter, Michigan

December 15, 1978

Preface

One might think, now that the world is falling down about our ears, that interest in a man whose entire career was with few exceptions dedicated to the eradication of domestic evils would naturally diminish in the face of danger from without. That, however, is not the case. My publishers have for some time been badgering me to dip once again into that battered tin dispatch-box in which I long ago packed away the last of my notes dealing with those singular problems which engaged the gifts of Mr. Sherlock Holmes, and to lay yet another of them before an eager public. For a long time I demurred — not because of any unwillingness upon my part but rather in deference to the wishes of my friend, who has since his retirement repeatedly enjoined me from taking any action to enhance fame which has of late proved cumbersome to him. The reader may imagine my reaction then, when, one day last week, I answered the telephone in my Kensington home and recognised Sherlock Holmes’s voice upon the line.

‘Good morning, Watson. I trust that you are well.’

‘Holmes!’

‘Whose call were you anticipating so anxiously, or does that fall under the heading of “most secret”?’

My surprise at being made contact with in this fashion by one for whom the telegraph remained the chief form of communication was heightened by this unexpected and accurate observation.

‘How did you know that I was expecting a telephone call?’ I asked incredulously.

‘Simplicity itself. You answered the infernal device before the first ring was completed.’

‘Wonderful! But what brings you to London? I thought that you had retired to the South Downs, this time for good.’

‘I am seeing a specialist about my rheumatism. I am afraid that the two years I spent trailing Von Bork did me no service. Have you still in your possession your notes regarding the affair in Soho in ‘84?’

I was caught off-guard by this seeming irrelevancy. ‘Indeed I do,’ I responded.

‘Excellent. I think that your readers may find some interest in the complete account. Mind you, be kind to Stevenson.’

‘The legal question —’

‘— is moot, I think, after all these years. Whitehall has far more important things to deal with at present than a thirty-year-old shooting, particularly one committed in self-defence.’

From there he steered the conversation into a discussion of the progress of the war, agreed with me that America’s entry into the conflict would spell doom for the Huns, and rang off after a talk of less than three minutes.

Since I have never pretended to any talents in detection, I shall not attempt to fathom his reason for dragging forth this long-buried memory, which would seem to hold little in common with the holocaust in which Europe finds itself at present. I had asked for and been denied permission to publish the facts of that case too many times to question this unexpected boon. To borrow a phrase from the Yanks, I am not inclined towards looking gift horses in the mouth; I shall, therefore, make haste to consult my notebook for the years 1883-85, set down the events as they occurred at the time, and concern myself with my friend’s state of mind upon some other occasion.

Holmes’s admonition to ‘be kind to Stevenson’ was unnecessary. Although it is true that Robert Louis Stevenson’s account of the singular circumstances surrounding the murder of Sir Danvers Carew contains numerous omissions, it is just as true that discretion, and not slovenliness, obliged him to withhold certain facts and to publish The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde under the guise of fiction. Victorian society simply would not have accepted it in any other form.

Now, after thirty-two years, the full story can at last be told. The pages which follow this preface represent variations upon the theme set forth in Stevenson’s largely accurate but incomplete account. As with any two differing points of view, some details, particularly those dealing with time, vary, although not significantly. This is due, no doubt, to the fact that my notes were made upon first-hand observation at the time the events were unfolding, whilst Stevenson’s were made upon hearsay at best, months and in some cases years after the fact. I leave the decision concerning whose version is correct to the reader.

As I write these words, it occurs to me that the story is in fact a timely one, in that it demonstrates the evils which a science left to itself may inflict upon an unsuspecting mankind. A culture which allows zeppelins to rain death and destruction upon the cities of men and heavy guns to pound civilisation back into the dust whence it came is a culture which has yet to learn from its mistakes. It is therefore hoped that the chronicle which follows will serve as a lesson to the world that the laws of nature are inviolate, and that the penalty for any attempt to circumvent them is swift and merciless. Assuming, that is, that there will still be a world when the present cataclysm has run its course

John H. Watson, M.D.

London, England

August 6th, 1917.

One

THE MYSTERIOUS BENEFICIARY

‘Holmes,’ said I, ‘I have a cab waiting.’

I was standing in the doorway of our lodgings at 221B Baker Street, hands in the pockets of my ulster and glad of its warmth now that the chill of late October had begun to invade the sitting-room in the absence of a fire in the grate. My fellow-lodger, however, appeared oblivious to the cold as he busied himself at the acid-stained deal table in the corner, his long, thin back concealing from me his specific operations. Nearby, studying the proceedings in baffled fascination, stood a broad-shouldered commissionaire in the trim uniform of his occupation.

‘One moment, Watson,’ said Sherlock Holmes, and executed a quarter-turn round upon his stool so that I might see what he was doing. With the aid of a glass pipette he drew a quantity of bluish liquid from a beaker boiling atop the flame of his Bunsen burner and expelled it into a test tube which he held in his left hand. Then he laid aside the pipette and took up a slip of paper upon which was heaped a small mound of white powder, curling it part way round his thumb so as not to spill any of its contents. His metallic grey eyes were bright with anticipation.

‘Purple is the fatal colour, Doctor,’ he informed me. ‘Should the liquid assume that hue once I have introduced this other substance — as I suspect it will — a murder has been committed and a woman will march to the gallows. Thus!’ He tipped the powder into the tube.

The commissionaire and I leant forward to stare at the contents. The powder formed curling patterns as it descended through the liquid, but long before it reached the bottom it dissolved. In its place, a stream of bright bubbles sped to the top and floated there. Holmes drummed the table with impatient fingers, awaiting the expected result.

The liquid retained its bluish tint.

I am not by nature an envious person, and yet, as moment followed upon moment with no change in the colour of the concoction in the tube, I confess that I had all I could do to maintain my countenance in the presence of Holmes’s undisguised bewilderment. He seemed so invariably right that I can scarcely describe the elation which I as a mere mortal felt to witness a rare moment of fallibility upon his part, proving that he, too, was subject to the frailties of the race. Fortunately for our relationship, my efforts to control my own mirth became unnecessary when he burst out laughing.