Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

Dreamtime is a visionary work of myth, memory, and spiritual excavation by one of Ireland's most original thinkers. In this profound journey of the soul, John Moriarty draws from global mythologies, literature, and personal experience to uncover the shared stories that shape human consciousness and the natural world. Woven through with richly poetic language and startling philosophical insight, Moriarty reconnects Western culture with the sacred imagination it has long forsaken. From Aboriginal Dreamtime to Homer, from Celtic folklore to Christian mysticism, Moriarty travels widely and fearlessly through the symbolic landscapes that have animated human life for millennia. The task of the poet-philosopher, Moriarty suggests, is to enlarge our capacity for symbolic understanding, while keeping the path to Connla's Well open and inviting us to inhabit a shared Dreamtime Dreamtime is not just a book—it is a re-enchantment, a call to awaken the mythic soul and to live in harmony with the Earth and its ancient wisdoms. A Book of Revelations grounded in sense as in spirit, Dreamtime refuses known categories, invites fresh modes of understanding and contains multitudes, introducing the reader to 'the splendour and terror and danger and wonder of a world everywhere and in everything eruptively Divine'. This is a powerful work of literature by a masterspirit of modern times.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 573

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

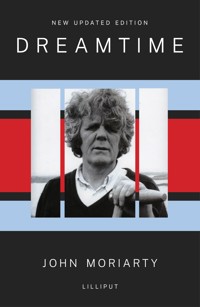

DREAMTIME

OVERLEAF : The Paps of Danu, Sliabh Luachra, Co. Kerry (Courtesy Rex Roberts ABIPP)

DREAMTIME

John Moriarty

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

Copyright © Estate of John Moriarty, 1994, 1999, 2009, 2020,2025 Afterword © Conor Farnan, 2025

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior permisson of the publisher.

First published in 1994.

This revised, expanded edition published in 1999,

reissued in 2009, amended 2020 and 2025 by

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

62-63 Sitric Road, Arbour Hill,

Dublin 7, Ireland

www.lilliputpress.ie

A CIP record for this title is available from The British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84351 965 2

eISBN 978 1 84351 293 6

Set in 11 on 13 point Garamond 3

Printed in Czechia by Finidr

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Ces Noidhen

Humanity at Bay

A Shudder in the Loins

Ollamh Fódhla

Fintan Mac Bóchra

Adventure

Challenge

The Naked Shingles of the World

Triduum Sacrum

Job and Jonah

Crossing the Kedron-Colorado

A Tenebrae Temple

The Wandering Christian

Altjeringa Rock

The Sword in the Stone

The Dolorous Stroke

Stone Boat

The Third Battle of Magh Tuired

Ata Dien Cecbt Do Liaigh Lenn

Inis Fáil

Hawk over My Head, Horse at My Door

Aisling

Mórdháil Uisnig

Europe’s Year One Reed

Ulropeans

Mona, Our Moses

Ragnarok and Ginnungagap

The Therianthropic

Kathodos

A Songline of the Greek Dreamtime

A Songline of the Hebrew Dreamtime

Ancient Sleep

Rift Man

Crossing the Kedron

Watching with Jesus

The New Heroism

Passover

Redeeming Our Heroes in the Light of the Triduum Sacrum

Healing the City

Holy City

Ragnarok

Bastille Day

Immram Eva

Sila Ersinarsinivdluge

Shaman

Prothalamion

Connla’s Well

The Realm of Logres

Morgan Le Fay, Our Mayashakti

The Mind Altering Alters All, Even the Past

Missa in Nocte

Partholon

Coming Forth by Day

Sumer Is Ycumen In

Before Sheela-na-Gig Was, Danu Is

Mandukya Dawn over Danu’s Ireland

Second Coming Christianity

A Ceiling of Sibylline Visions for the Ruined Cathedral of Clonmacnoise

Imagine

The New Gae Bolga

Enflaith the Bird Reign of the Once and Future King

Epilogue: The Last Eureka

GLOSSARY

SOURCES

AFTERWORD The Humours of Moriarty

INTRODUCTION

The first and obvious question: why the title, why ‘Dreamtime’?

‘Altjeringa’ is a very beautiful Australian Aboriginal word. To me, at any rate, it is very beautiful. It means the Dreamtime, or the Dreaming, that was in the beginning. As Aborigines imagine it, the earth in the beginning was a featureless waste, but beings called the Altjeringa Mitjina, the Eternal Ones of the Dream, emerged, and they went walkabout, each in his or her own way, across this featurelessness; and as they did so, they dreamed with the dreaming earth, dreaming now of a river, now of a mountain, now of trees; and the rivers, the mountains, the trees, the vast variety of things they dreamed of, came to exist objectively and independently of the Altjeringa Mitjina who dreamed them. And so it was that the earth as we now know it came to be. And so it was also that the culture came to be, culture having its origin in things said and done in the beginning. It is this latter aspect of the Dreamtime that I had in mind when I chose the title.

How, structurally and thematically, does this concept of Dreamtime have a bearing on this book? In what way or ways did it help to generate it, motivate it, shape it?

We live in what Hölderlin and Heidegger would call a destitute time. And both Hölderlin and Heidegger ask, What are poets for in a destitute time? The answer implied but not overtly stated in this book is that poets must be healers—healers who, healed themselves, heal us culturally, heal us, or help to heal us, in the visions and myths and rituals by which we live, and to do this effectively they must in some sense be Altjeringa Mitjina, temporary ones, not eternal ones, of the Dream.

Do you see a part of the purpose of the book as enacting and integrating that healing?

Yes, I suppose so. The hope is that, however ethnically various it might be, there is a European Dreamtime. The hope is that Dreamtime always is, is everywhere, is now, and that there are people who have access to it. It is sometimes the case, isn’t it, that individuals are healed as they are at present only as a consequence of having been healed as they were in their past?

As with individuals, so, sometimes, with a whole people. Healing in our cultural present will come as a consequence of healing in our cultural past. Out of a healed past a healed present will grow. Out of a re-realized past a re-realized present will emerge. It is as necessary that we realize a past out of which to grow as it is to realize a present and future into which to grow. Our past we have always with us. Our past we must always re-realize. And to do this we need people who can live in our cultural Dreamtime, people who go walkabout, creatively, within the old myths, people who go walk-about into the unknown. It isn’t wise, I believe, to do what the originators and executors of the French Revolution did or sought to do. Seized by revolutionary fervour, they would have wiped the slate clean. Intending to hang the last king in the entrails of the last priest, they installed a statue of reason in Notre Dame. But it might be no harm to remember that just as there is an irrational misuse of the irrational, so also is there an irrational misuse of the rational, and that this latter misuse is often as terrible in its consequences as is the former.

Could you locate the book in the context of other writings in the Western tradition?

If you pull back far enough from it, I think you will see that it is an aisling. The word aisling is a Gaelic word that means vision, or, better perhaps, dream-vision, and in Ireland, from the eighteenth century on, it gave its name to a kind of poem that was popular among people who, religiously, politically and economically, had been dispossessed. In the typical aisling, the poet wanders in a lonely place, or falls asleep in a lonely place, and in a dream-vision he sees a beautiful woman. Invariably, the poem goes on to enumerate and lavishly describe her beauties of feature and form. Then the poet asks her who she is and she, calling herself by one or another other poetic names, reveals that she is Ireland, adding that she is in deepest sorrow and distress because she has been ousted from her rightful inheritance. Heroically, then, the poet declares that he will fight, unto death if necessary, in her cause, and the poem ends with a vision of the old order restored, of Ireland restored to her ancient inheritance, of Ireland once again having the walk of a queen.

That, briefly, is what a typical aisling might read like. In Dreamtime, however, it isn’t only Eire who is in trouble. Europa is in trouble. Ecclesia is in trouble. Eire, Europa and Ecclesia are, as it were, three women at a Hawk’s Well. Sitting there in deepest gloom, like Dürer’s ‘Melencolia’, they are waiting for the healing waters to flow. Waters that will heal them of their Medusa mindset. Waters that will release them back into their Dreamtime.

But surely anyone who is aware of recent Irish history couldn’t, in good conscience, write an eighteenth-century aisling? To do so would be to give further voracious life to the old sow that devours her farrow.

That’s true. But, while I think of what I’ve written as in some sense an aisling, I do hope that it doesn’t read like an eighteenth-century aisling. For one thing, it doesn’t stand on sectarian ground, or on racial ground, or on socio-economic class ground. Twice or three times it crosses the Kedron with Jesus and stands Grand-Canyon deep in the world’s karma. And, although in many pieces there is an attempt to bring together the two extremities of the Indo-European expansion, when they do come together, when they come together creatively, they do so at the heart of the Triduum Sacrum, which is Semitic. The Triduum Sacrum is the athanor of their chymical wedding.

Where does this leave Dreamtime? If it isn’t an eighteenth-century Irish aisling, what is it?

I don’t know, in any simple formula, what it is, I only know that it isn’t a thesis. It resists being a thesis. It resists linearity. It is a tapestry of themes and styles, and the hope is that when we come to the end and stand back, we will see that a unified picture does indeed suggest itself. Order will be seen to emerge from chaos. And there is, in any case, an aesthetics of emergent order, just as there is an aesthetics of achieved order. And it might indeed be that in our quest for a vision by which to live, we will sometimes have to be content with an aesthetics of chaos. Waddington, who was a fine scientist, has said nature doesn’t aim, it plays. And we aren’t perturbed when, reading a book of poems, we find that they differ one from another in theme and form. In spite of its inner variety, such a book might yet come across as a single, if complex, vision of reality.

So, in your own experience of your own book, does it, do you think, have an architecture, a structure, an order?

I think it does. To give you a sense of what it is I will quote a passage from Apocalypse by D.H. Lawrence: ‘To get at the Apocalypse’, he says,

we have to appreciate the mental working of the pagan thinker or poet—pagan thinkers were necessarily poets—who starts with an image, sets the image in motion, allows it to achieve a certain course or circuit of its own, and then takes up another image. The old Greeks were very fine image-makers, as the myths prove. Their images were wonderfully natural and harmonious. They followed the logic of action rather than reason, and they had no moral axe to grind. But still they were nearer to us than the orientals, whose image-thinking often followed no plan whatsoever, not even the sequence of action. We can see it in some of the Psalms, the flitting from image to image with no essential connection at all, but just the curious image-association. The oriental loved that.

To appreciate the pagan manner of thought, we have to drop our own manner of on-and-on-and-on, from a start to a finish, and allow the mind to move in cycles, or to flit here and there over a cluster of images. Our idea of time as a continuity in an eternal straight line has crippled our consciousness cruelly. The pagan conception of time as moving in cycles is much freer, it allows movement upwards and downwards, and allows for a complete change of the state of mind, at any moment. One cycle finished, we can drop or rise to another level, and be in a new world at once. But by our time-continuum method we have to trail wearily on over another bridge ...

That I think describes the aesthetics of Dreamtime. It is image-thinking, and it moves in cycles. It is a kind of music, and pieces that read like repetitions are leitmotifs. One of these leitmotifs constitutes a kind of loosely structuring plot. I am thinking of the king motif. The book opens with a story from the Mabinogion which is re-told. In this re-telling of it, it becomes a story of a king in trouble. There is an idea, some would call it a primitive idea, that if a king is in trouble, then a people is in trouble, and the land they inhabit is in trouble.

Somewhere towards the centre of the book there are two stories, the theme of which is the healing of the Fisher King and his realm, now, as a consequence of his wound, a tière gaste, a wasteland. You will remember, maybe, that, according to the prose Perceval, the Fisher King lives in Ireland. He is the Maymed Kynge that we meet in Malory’s ‘The Tale of the Sankgreal’. He is our Riche Roi Méhaigné.

In the final story of the book a man emerges from a pre-Celtic tumulus tomb like Newgrange and walks naked towards Tara, carrying the sun-spear in his hand. He is both Pwyll and Arawn of the first story. He is king of both worlds, this world and the Otherworld. He is, very obviously of course, a type of the risen Christ, whose father also, if only iconographically, was a bird. The sun-spear he carries isn’t a warrior’s spear, it isn’t an tsleg boi ac Lugh. Neither is it Cuchulainn’s Gae Bolga. It is the spear of light that enters Newgrange at the winter solstice. Carrying that spear, a spear by which he was himself transformatively killed, he will re-establish his ancient Bird reign in Ireland. To begin with in Ireland.

As Nemglan, the Birdman in the waves, had said to him:

Bid saineamail ind énflaith.

Your Bird reign shall be distinguished.

During his Bird reign the waters of Connla’s Well will flow again, the healing waters of the Hawk’s Well will flow again, and Eriu, Europa and Ecclesia will come home bearing brimming water-jars on their heads.

So your book, after all, is an aisling of a kind?

Perhaps you can call it an Altjeringa aisling. It goes back to and comes forward from the Celtic, Judaeo-Christian and European Dreamtimes. As I was writing it, I had a sense that I was attempting to write a Blakean Prophecy. I am thinking of the Blake who would awaken Albion. Speaking of Blake, Kathleen Raine remarks that the myth of the king who sleeps but will one day awaken is the great and perennial British myth. She tells a lovely story: one day, taking time off from tending his flock, a shepherd was knitting a scarf. Moving himself to ease an ache in his back, his ball of thread slipped from his lap and rolled a little way down the hillside, disappearing through a cleft in the rock. Entering through the cleft, the shepherd found himself going down into a cave. There he saw a sleeping king and on a table beside him a sword and a horn. The shepherd took this sword and struck the table. The king opened his eyes and raising himself said: You should have blown the horn. Reclining again, he went back to sleep.

That’s it, I suppose. Dreamtime attempts to blow the horn.

Conaire has awakened.

Conaire, whose Bird reign will be distinguished, is walking naked to Tara. And, corresponding to the claidheamh solais of the Celtic Dreamtime, the spear he is carrying is a tsleg solais, for Conaire isn’t only a type of Christ coming forth from the tomb—he is also Plato’s Philosopher King coming forth from the cave.

Walk on Conaire.

Bid sameamail ind énflaith.

It is time to sing,

Tá na bráithre ag teacht thar sáile’s iad ag triall ar muir.

The friars are coming over the brine and journeying on the sea.

They are bringing Second Coming Christianity. They are bringing Upanishads and Sutras and the Tao Te Ching. They are bringing the Mandukya Om.

Our Carraig Choitrigi is our new Carraig Donn, our new Carraig Om.

We have a centre that will hold.

DREAMTIME

Animum debes mutare, non caelum

CES NOIDHEN

Towards the end of the last century, Yeats and Lady Gregory spent many days together collecting folklore in the countryside around Coole in the west of Ireland. In the course of their work they discovered that

When we passed the door of some peasant’s cottage we passed out of Europe as that word is understood.

The Europe they here have in mind is of course official Europe, the Europe that continues to have its cultural origins in Hebrew prophecy, Greek philosophy and science, and Roman law.

And now at last a door, and we lift the latch, and the voice that says come in could be the voice of Fintan Mac Bóchra. It could be the voice of Merlin or Taliesin. It could be the voice of Morgan le Fay.

And how strange it is to stumble on the path that takes us to that door. And how strange it is to lift that latch. And how strange it is to hear that voice. And how strange it is to discover we were always so near home.

Coming again the next day, that path might not be there.

There, but not there for us.

Not there for us because now again we have no eyes for it.

Our eyes are for seeing hard facts.

Hadrian’s Wall is a hard fact.

First, it fenced us into a world of hard facts.

Now, stronger than ever, it fences us into a world of manufactured hard facts, it fences us into official Europe. And we don’t even wail at it. Nor do we take a sledge to it. It is within a great prison we are unconscious of that we celebrate our Bastille Day.

Almost from the beginning, the wall that Hadrian had built across the north of England became an inner wall. A defensive wall, it has served its sundering purpose only too well, and we, its prisoners, we have gone on building it, deepening it, widening it, filling up cracks in it. Fortunately no crack was wide enough, not even the crack we call Romanticism was wide enough, to let Merlin walk through.

From before a foundation stone of it was laid, Aristotle had a hand in it. More recently, Descartes had a hand in it. On a morning when he celebrated Christ’s nativity, Milton had a hand in it, forced his Saviour, infant though he was, to have a dreded hand in it. Locke had a hand in it. Indeed, all rationalist and empirical philosophers had a hand in it. Hardly an eighteenth- or nineteenth-century scientist but had a hand in it.

We have gone on building your wall for you, Hadrian. Building it inwardly and outwardly against shamanic Eurasia. Building it inwardly and outwardly against Faerie. Building it inwardly and outwardly against our Dreamtime.

Against Merlin, Taliesin and Morgan le Fay.

Against Boann, Badb and Cailleach Beara.

Against Ollamh Fódhla.

Against Fintan Mac Bóchra.

Against Pwyll, Prince of Dyfed.

It wasn’t by sitting at home, waiting for a turn in the weather, that Pwyll came to know where a stag hunt might lead if it led to Glen Cuch.

It wasn’t by sitting at home, waiting for the spring run of salmon in the river, that Pwyll found the crone and the crone found the well where he slept for nine nights, on nine hazel wattles, seeking a vision his people could live by.

It wasn’t by sitting at home, waiting till his minstrel had come to the end of his winter cycle of stories, that Pwyll rode back one day, his banner of lordship in the Otherworld streaming behind him.

Pwyll in our world meant the heraldry of the Otherworld in our world. Streaming from tower and outer wall, they would brighten a sad day in Dyfed.

It was the time of year when Pwyll and his men-at-arms rode to his court in Arberth. The sun picking out great braveries of armour and ornament, they rode four abreast and, to a man, they had the look of men who lived in hill-forts and worshipped in henges.

Theirs was a world that had genius in every stone and bush of it, and it wasn’t by incantation that a bush would enchant you, leaving you helpless, your hand halt, and your sword hanging idle at your thigh. Rough men though they were, and intent on adventure, not one of them but knew when to rein in his horse. Riding together or alone, riding at nightfall in desolate places, not one of them but knew when to rein in his instincts.

It was that kind of world. A man who had won everlasting renown in a long war might die coming home when a hare who wasn’t a hare of this world put an eye that wasn’t an eye of this world upon him. Upon him and his horse.

To die in circumstances such as these was, more often than not, to be called away to a glorious life in a glorious elsewhere.

Of such a man his companions and neighbours would say that he had been swept. By whom they would, in awful reverence, rarely say. Any yet everyone knew that it was the Aes Shidhe.

The world he had gone into wasn’t far away. Nights there would be when people would hear overhead the hosts of the air go riding by and someone who had second sight would recognize the dead man, glorious now on a glorious steed, riding among them. And it was well known that a woman who loved a swept man could, in a ritual performed at a crossroads, induce him or even compel him to come back.

It was that kind of world.

It was a world of worlds, all of them one world, all of them a world in which there was coming and going between worlds. As often as not, Pwyll Prince of Dyfed was called Pwyll Pen Annwn, Pwyll who was Head of the Otherworld.

Like all of us, although in our case at an unknown or unrecognized depth of ourselves, Pwyll was a Lord in two worlds. Had the banners of two worlds flying from his towers.

Every year, at leaf-fall, Pwyll and his men rode to Arberth. Riding through a valley five valleys from home they were like an old story Taliesin would tell. And they had it in them to go with the story. They had it in them, living now, riding now to Arberth, to be a tale told by a fireside in the far past, to be a tale told by a fireside in the far future. And they would say, would sometimes say, that their only reason for being in the world was to give the world a chance to live out its own strangeness, its own danger, and its own wonder in them. And this year, reaching Arberth, that’s what they looked like. They looked like men who had survived. They looked like men who had come through a dream that Ceridwen, having drunk a new brew from her cauldron, had of them.

After meat and good cheer in his hall the next day, Pwyll announced, as though something had come over him, that he would now go out and sit on the throne mound. At his bidding, a score of men, and they the bravest, accompanied him.

Famous in all worlds, even in worlds we rarely cross into, the throne mound in Dyfed was called Gorsedd Arberth. A thing of crags and swards, of furze and whitethorns, it was lair to a man’s own fear of it. It was lair to his fear of himself. In some of its moods, horses, in screeching refusal, would rear at it. And so, it wasn’t in ignorance of its perils that Pwyll climbed it. Today, sitting there, he knew that one or another of two adventures would befall him: either he would endure wounds and blows or he would see a wonder.

It was Teyrnon Twyrf Liant, Lord of Gwent Is Coed, who first saw it: in fields all about them not a horse but had stopped grazing and was looking intently, as if in a trance, towards the wood.

Pwyll was of the impression that they were looking into a depth of themselves and into a depth of the world that only the most privileged of us have ever walked in.

Persons so privileged, Pwyll was aware, had rarely come back.

Although he could never afterwards say how or why, Pwyll had come back, a pennant and banner of the Otherworld streaming above him in the January wind.

And as he once came home having slept for nine nights on the nine hazel wattles, so now he came home with a boon for his people. He had news for his people: the Otherworld is a way of seeing this world, it is a way of being in this world.

And still the horses were entranced.

And sure by now that it wouldn’t be blows and wounds, Pwyll expected a wonder.

And a wonder, yes, a wonder she was.

She was riding a roan horse.

The roan horse she was riding had red ears.

As soon as she had fully emerged from the wood, the horses of this world neighed.

And the horse the high woman was riding, the horse with red ears, she neighed.

And then it happened.

Not a man on the mound but was utterly helpless, utterly struck down. It was with each one of them as it is with a woman in labour.

And it went on.

And it went on.

And it went on.

They had come to defend Pwyll. But not a hand let alone a sword could any one warrior lift.

And it went on.

And it went on.

And then as mysteriously as they were afflicted they were released.

When at last they could come to their feet and had vision for things outside themselves, they looked and saw that she was gone. And strangest of all was how utterly like its old self the world was. As if nothing had happened, a robin was singing.

As if nothing had happened, the horses were grazing.

On each of the three following days things fell out as they had on the first.

Pwyll and his men went to the mound.

In fields all about them the horses stopped grazing and, standing there in a trance of vision, they looked towards the wood.

The woman emerged.

Two worlds, one of them our world, neighed to each other.

And then, more frightful every day, more frightful because more intense, the labour pains of Pwyll and his warriors.

In a vision they would have of it, in their moment of deepest affliction, the throne mound in Dyfed was a red mound. It suffered as they suffered. In the way that Pwyll suffered the crags suffered, the furze suffered, the thorns suffered. For as long as it lasted, this suffering was the ground of their oneness with each other. For as long as it lasted, Pwyll might as well have been a thorn, red with haws, on the side of a hill.

It was strange.

A power against which spear and shield and sword were useless had emerged among them. And what, as warriors, they would most instinctively resist, that was happening to them.

Being warriors though, they would see it through to the end. They would go everyday to the mound. And even if it meant that he would indeed end up as a bush, too haunted and too dangerous for anyone to approach, too haunted and too dangerous for anyone to pick haws from— even if by doing so that is what would happen to him, Pwyll would nonetheless go everyday to Gorsedd Arberth. He would sit where all previous kings of Dyfed had sat. He would sit in the chair, called the Dragon’s Lair, between the crags. It was only in the engulfing danger of this chair that he could do what he was born to do. It was only in a willing self-sacrifice of all that he was in all worlds that he, Pwyll Pen Annwn, could mediate between them.

The burden of Pwyll’s destiny was simple, and dreadful: a world that is cut off from other worlds will soon die.

Come what may, therefore, Pwyll must go to Gorsedd Arberth.

It was late on the sixth day when Pwyll and his men recovered their eyesight for things outside themselves. Wondering what it might portend, they saw that instead of turning her horse and riding back into the wood she had slackened rein and was coming along the road that passed beneath them.

At Pwyll’s request, Teyrnon Twryf Liant rode, as courteously as he could manage it, to meet her.

But how can this be, he thought reaching the road, how can it be that she who rides so slowly and at such an even pace has already gone past?

Putting spurs to his horse, he gave chase.

In a short while he was riding at full stretch, and yet, even though she continued in her unhurried, slow pace, the distance between them continued to lengthen.

Soon she was out of reach and, discomfited in the way we sometimes are in our dreams, Teyrnon gave up and rode back to the mound.

Pwyll and his men, their arms at ease, returned to the court.

Again the next day, after meat and carouse, they went to the mound.

It was as they expected. In fields near and far there was not a horse but had stopped grazing. As in previous days they were looking enraptured at the wood.

Anticipating what would happen, Pwyll had asked his best rider to fetch the bay, his best horse, from his stables. He was on the mound, mounted and waiting, when she emerged. He rode to meet her.

Great was his wonder when, reaching the road, he saw that she had gone past.

He gave chase.

In a while he was riding at five times, six times, seven times her pace, and yet, she never changing demeanour or motion, the distance between them continued to grow.

On the day following, Pwyll was alone on the mound. Mounted and waiting, he showed spurs to his horse as soon as he saw her.

But no!

When he reached the road she had gone past.

He gave chase.

Never did a horse know so well what was expected of her.

Never had a horse such heart for hard riding.

Never did a horse yield so at length to her rider’s desire.

But no! No!

It was all in vain.

The echoing hills carried his call

Stay for me

Stay for me

In the name of him you best love, stay for me.

On a crag, looking down at him, she waited.

Who are you, he asked? Who are you and what is your errand?

My names are many, she replied. There are those who call me Epona, those who call me Macha, those who call me Rhiannon. But by whichever name they know me, they know me only as a woman who rides a roan horse. A horse with red ears. You, however, you have seen the enraptured horses.

You have seen my demeanour and motion. So you know who I am. I am who you feared, yet hoped, I might be.

And your errand? Pwyll asked.

You’ve already suffered it, you and your men.

And must we continue to suffer it?

That is for you to choose. It’s by choice from now on.

Turning her horse, she rode away, and soon she was out of sight, gone into another way of being in our world.

And that’s how it happened.

That’s how, after long ages, the Horse Goddess came to us, bringing us the terrible yet perfect gift of suffering her labour pains with her.

She foals on May Eve. But for anyone who at anytime chooses to endure them, her labour pains are a door between ways of being in the world.

Will you walk through it Hadrian?

And you Europa, will you walk through the labour pains of the Horse Goddess into our Dreamtime?

HUMANITY AT BAY

One morning, not enchanted, no spell at work in me, no recurring dream having forced my hand, I was rowing a first boatload of saplings across a clear lake. Looking at the mirrored mountains I marvelled at the lake’s hospitality to things as they are. Such sight, unfalsifying and unafraid, is the only second sight I would ever ask for. I didn’t ever ask for it, because ancient life in me has ancient needs, has ancient ways of seeing things.

Some nights an old story would be my element. Living in it, letting it live in me, I’d draw big waking and big dreaming from it. I drew big dreaming and big waking from this old story, one of the many stories a mabinog, an apprentice bard, must know:

Pwyll, prince of Dyfed, was minded one day to go hunting. There was more to the world in those days than there is now. In those days the world had many marvellous elsewheres in it. Suddenly, the hunt at full stretch maybe, a horse would rear, and rear, and rear again, wouldn’t be mastered, would refuse most savagely to go forward. Sooner than his rider sometimes a horse would sense entry into another world.

It was into this world of many worlds, his hounds, like himself, scenting sirloin, that Pwyll, prince of Dyfed, rode one day.

The chase and the dangers of the chase, wherever it would be, lured him on. Five rivers from home the world was darker and wilder than he had ever known it to be.

Some valleys he rode through were an exasperation of crags and woods and waterfalls.

In the narrowest valley of all, overhung by great draperies of mist and light, the world kept its craggy, mountainous mind to itself.

He had heard about such places. He had heard about rock walls that wouldn’t even send back an echo.

Today, Pwyll had ridden farther into the world than was his wont.

In Glyn Dhu he saw only a stooping hawk.

In Glyn Cree he saw cast antlers.

In Glyn Cuch he heard howling. He heard baying coming closer. Coming suddenly into view, then suddenly turning, a stag stood at bay in a clearing below him. Hounds that snapped at him were like none he had ever seen. In colour they were white with red ears.

Riding down to them, mastering his horse in tighter and tighter circles among them, he drove them off.

Baiting his own pack he was when someone, in person and poise most kingly, came riding towards him.

You do me great discourtesy, the kingly stranger said.

How so? asked Pwyll, fronting him, not aggressively, but inquiringly, with his horse.

You are baiting your hounds on a stag my hounds have pursued since noon.

Pwyll was abashed. You will favour me greatly, he said, if you will let me know in what way or ways I can make amends.

Arawn is my name, the stranger said. I am king of Annwn. And Annwn, as you know, is the farthest yet also some days the nearest of otherworlds. Like this world, it is sometimes in some places other than itself. In some places, sometimes, it is its own otherworld.

And yes, he said, yes, there is for you a way to make amends. In Annwn, were it not for Hafgan, there would be peace and plenty. Hafgan is most cruel. He comes every night from beyond a deep river raiding our country with fire and sword. You would make amends and you would furthermore win our friendship forever were you, by killing him, to bring to an end the hurt and the terror we suffer at his hand.

Gladly will I assay the killing of him, Pwyll replied. But how best may I encompass it?

To that great end will I instruct and assist you, Arawn said.

I will in this regard, submit most happily to your good counsel, Pwyll averred.

So be it. In this wise, with your consent, shall we proceed. First and foremost, you and I must be friends. From faithful and strong friendship between us much good will follow. As for the rest, with regard, I mean, to the task you are willing to undertake, this is what I propose: leaving here you will go to Annwn in my stead. You will go not in your own appearance and shape but in mine, which I have power to make manifest in you. Assuming your appearance and shape I will go to Dyfed. Arrived there, I will be as you would be, I will do as you would do. In Annwn, when you come there, you will do as I would, you will hunt, you will feast, you will preside, moving in a royal progress from one to another, in my many duns and castles and courts, you will play chess with the chief seneschal, you will listen to wandering minstrels and resident royal bards, you will sleep every night in our bed with my wife who, I am bold to say, is fairer in looks, in her ways and walk, than any woman you have so far seen. A year from today you must ride out to joust with Hafgan at the ford. If it be in your power to do so, and I am sure that it is, see to it that you wound him mortally and unseat him in the first violent charge. In a show of most woeful pain, he will plead with you to end his life, but do not strike him. A second blow to Hafgan revives him, and be in no doubt about it, Hafgan revived is an altogether more awful opponent. Hafgan revived will win the day.

And so, good friendship between them avowed, they parted, Pwyll in the image and likeness of Arawn, its king, going home to Annwn, Arawn in the image and likeness of Pwyll riding home with his hounds from the hunt to Dyfed.

Great was the welcome for both, but great above all was the welcome for Pwyll when he arrived in the Otherworld.

Everything was as it would be were it Arawn himself who had come home.

From the moment, however, that he crossed its borders coming into Annwn, he had to cope with huge surprise. Like leaves that fall from a tree in autumn, his beliefs about Annwn fell from Pwyll, prince till today in Dyfed, leaving him bare.

The secret of Annwn, whatever it was, that he never revealed. His eyes opening as he crossed into it, he saw maybe that life in Dyfed was a forgetting.

It is only, maybe, when the forgetting of Dyfed falls from our eyes that we come into Annwn.

In Annwn we are awake to the Great Life. In Annwn we see.

Awake and with eyes to see in Annwn, Pwyll lived as Arawn would have lived. In only one thing did he not live like him. In bed every night he offered no tenderness or caressings of love to Arawn’s wife. However cold towards her it must have seemed, he would always lie on his right side facing the wall.

Images of himself he saw on that wall.

Images of himself as a wounded Bull, a wounded Birdman.

And so it was one autumn morning that his days and nights in Annwn were almost at an end.

There remained only one thing to do. And that he did. Riding to the ford, he encountered and killed Hafgan.

But the Hafgan within himself, the Hafgan impulses he would sometimes see, lying awake, on the wall—that was another story, and he rode out of Annwn one day not knowing the beginning or the end of it.

Riding in Glyn Cuch to his tryst with Arawn, he heard his own hounds, the hunt coming towards him. Out of a wood it burst, the stag suddenly turning, standing at bay. Riding into it he dispersed the pack.

Baiting the Otherworld hounds he had hunted all year with he was, when someone who looked like Pwyll, prince of Dyfed, approached. He was seeing himself for the first time. He was seeing himself with wide, Annwn eyes and that first humbling but healing vision of himself, he would never forget.

And there was worse: it was clear to him now, looking at himself outside himself, that during the year and a day he had spent in Annwn his appearance, borrowed though it was, had become his identity. His disguise had become his deepest guise. His disguise had become his destiny.

He dismounted.

Standing there. Stripped of disguise and guise, Arawn looking down at him from his high horse, he experienced his own nothingness.

So that was it. He saw it now. Pwyll, prince of Dyfed, had ridden out with his hounds to hunt in Glyn Cuch. Himself he alarmed. Himself he pursued. Himself he ran down. And turning at last, and facing his hounds, Pwyll, prince of Annwn, prince of Dyfed, stood at bay.

That’s an old story.

It is one of the many stories a mabinog must know.

I often listen to it.

Every time I listen to it, it runs me down.

Every time I listen to it I stand, like Pwyll, at bay.

But standing at bay, like Pwyll in Glyn Cuch, isn’t the end of the story. The story moves on. Or it will move on, beyond Annwn and Dyfed. And that’s why, every morning for months, I rowed a boatload of saplings across the clear lake. That’s why I planted a forest. The story might one day move into it. It moved into it in India and it emerged as Upanishads. It emerged as the Mandukya Upanishad, a classic text of Advaitavendata. Imagine it, the Mandukya Om chanted in a forest by the Bay of Bengal, chanted in a forest by Galway Bay.

Imagine it: the Mandukya Om chanted at the two extremities of the Indo-European expansion.

Hari Om.

A SHUDDER IN THE LOINS

Had he, under tutelage, disciplined the savagery that was in him, and the generosity that was in him, Crunncu might have been a great warrior. As it turned out, he ended up alone, discovering once to his cost that he hadn’t, like his cattle, lost his wildness.

Afterwards, as much as he could, he avoided fairs. And assemblies of his people at Bealtaine and Samhain, and assemblies in honour of Crom Dubh, them also he stayed away from.

His four unbroken horses coming down the hillside after her, she came.

His door was open.

I’ll be a woman to you, she said, going to the fire and putting fresh logs on it.

Wild though she was, one of the horses put her head through the door.

Not wishing to give the impression that his house was a stable, or that he lived with his animals, Crunncu went towards her, threatening her.

She didn’t move.

The horse and the woman looked at each other.

They looked a long time at each other.

At exactly the same moment, nothing overtly happening between them, the woman turned to her work, the horse backed away, and realizing he was out of his depth, Crunncu asked no questions.

Unsure of himself, he went out.

He stayed out all day, gathering his dry cattle and herding them to higher grazing ground.

The higher view didn’t help him.

Heights today didn’t mean elevation of thought or of feeling. Being higher than the highest wild goat, being higher than a peregrine falcon bringing wool to her nest, to Crunncu up there looking down on his life’s work that meant, not delight, but defeat. Bracken and furze had all but taken over his world. Yet, even now, when last year’s bracken was tinder dry, he wouldn’t fire it. The fired bracken would fire the furze, but he thought of all that wildness going up in smoke, that was a price he wouldn’t pay. Wild nature outside him, letting it be, that was his sacrifice of appeasement to wild nature inside him. Religiously, in ways such as this, Crunncu coped.

Shoulder deep in furze, flowering now, he walked back to his house.

A changed house it was.

Nothing had been altered, nothing disturbed, not even the five cobwebs in the five hanging bridles had been molested. And that reassured him. In firelight, now as always, they looked like death masks. Masks of something dead in himself, he sometimes thought.

No, in outward appearance nothing had changed. And yet, particularly at threshold and hearth, it was as if the house had undergone rededication. But to what he didn’t know.

Who is she? he wondered, watching her skimming the evenings milk.

Had she come bringing last year’s last sheaf of corn, he’d have thought she was the Corn Caillech.

Had she come, walking tall and naked, and holding a spear, he’d have thought she was Scáthach.

Had she come, a lone scaldcrow calling above her, he’d have thought she was Badb Catha.

Had she, having come, opened her thighs and showed her vast vulva he’d have thought she was Sheela-na-Gig.

Awake, he wondered.

Asleep, he wondered.

Who is she? he wondered, watching her rear like a horse in his dreams.

And the horse that so regularly came to stand in their door? Shoulder deep in the morning, eyes deep in the evening, what did that portend?

There was, he sensed, something he knew about her. But he knew it only where it was safe to know it, in dreamless sleep.

And he wasn’t a man to her yet. And in the way that a woman is sometimes a woman to a man, she had so far showed no sign that she wanted to be a woman to him in that welcome way.

And how could any man be a man to a woman like her? How, he looking at her, and she looking at him, could he lay a desiring hand upon her? Would she, showing her teeth, rear like a horse as she did in his dreams?

Sitting across from her by the fire one evening, something dawned on him: Until she came his house had sheltered him, but only as a shed might shelter a cow. Like a religion now, it sheltered him inwardly. Like a religion that was there from the beginning, like a religion that had grown with the growing world, it sheltered him in his difficult depths.

It was strange.

A horse, and she not broken, standing shoulder deep

In his door every morning

A horse, and she not broken, standing hip deep

In his door every evening.

From hip deep in his nature the dream came: walking high moors he was when he came upon it, the tall standing stone. Taller than a man, it was a man’s member, or a god’s member, and it was suffering. As a woman in labour suffers, it was suffering. And then, up from the roots a shuddering came, upwards it shuddered, upwards it surged into a long releasing scream that awakened Crunncu, and lying there he knew that in some strange way he had been a man to the woman who was lying beside him.

Welcome to the great world, she said.

Terror of what had happened was shaking Crunncu.

Till dawn it continued, shaking the shaken foundations of old established mind in him, of old established mood in him.

I’m ruined, he said.

Walk through the ruins, she said.

Walk through the ruins you’ve already walked through.

Walk in the great world you’ve already walked into.

It’s a nothing, a nowhere, I’ve walked into, he said.

No more marvellous place than that nothing, that nowhere, she said. It’s God, she said. It’s the Divine behind God, behind all gods, she said. It’s the Divine out of which the gods and the stars are born, she said.

My name is Macha, she said.

For the first time since waking Crunncu opened his eyes, opened them in anger, in dangerous, frightened anger.

We should never call anyone Macha but Macha, he blazed.

Do you hear me? We should never call anyone Macha but Macha. Macha’s name is a holy name. It belongs to no one but Macha. To no one, no one. To no one but Macha.

His anger became religious indignation, he fixed her in a cold stare: your name isn’t Macha! In this house it isn’t Macha. I keep horses for Macha. In honour of Macha, in praise of Macha, in thanksgiving to Macha, I never, not even in a moment of greed, I never attempt to bridle them, I never attempt to break them in. Wild on the hills, neighing on the hills, their manes and their tails streaming in the hills, they are the glory of Macha. They are the nearest we can ever come, safely come, to a vision of Macha.

In her nature Macha

In her name Macha

Sharing neither nature nor name with anyone, that is Macha.

Taking Macha’s name you have sinned against Macha. Taking Macha’s name you aren’t safe to sit with, you aren’t safe to eat with, you aren’t safe to live with, to lie with. What I cannot understand is why our cow hasn’t run dry, is why our well hasn’t run dry. In my house, no! In my house your name is not Macha.

By what name then shall I be known?

By the name of my neighbour’s nag.

What’s her name?

She has no name. Nag is her name. And it’s your name. Until you find favour with Macha, it is your name. Nag is your name! Nag!

And how might that be? How might I find favour with Macha?

That’s for Macha to decide. She might never decide. Macha’s heart can be hoof hard. And her head! No! Macha’s holy head has never been bridled. Cobwebs blind the bridles we would bridle Macha with. The bridles we would bridle Macha with are masks of our own terror. Attempt to bridle Macha as you’d attempt to bridle an ordinary horse, attempt it, just that, and your face will fall in, into nothingness, into emptiness, into your own empty skull looking back at you as the bridle you’d have bridled her with.

Macha is lovely

Macha is ugly

Macha is gentle

Macha is vicious

Macha has arms

Macha has hooves

The most beautiful of women is Macha: she opens her thighs and you see a mare’s mouth.

Macha is Life

Macha is Death

Bigger life than the life we live is Macha

Bigger death than the death we die is Macha

With no ritual have we bridled Macha.

With no religion have we broken her in.

In no temple to Macha have we stabled Macha.

Everything in the world that we aren’t able for, that’s Macha.

Everything in ourselves that we aren’t able for, that’s Macha.

Everything religion isn’t able for, everything culture isn’t able for,

That’s Macha.

Stories we have that can cope with Crom Dubh.

No story we have or ever will have can cope with Macha.

Search our stories, our Tains and Toraiochts, and in them you’ll find not a hoof-mark of Macha, in them you’ll find not a shake of her tail.

No! No! Neither Tain nor Toraiocht has covered Macha. Rising on its hind legs like a stallion, our Aill at Uisnech hasn’t covered Macha.

Living in a world as wild as this one is, the only goddess or god I leave a door open for, and leave a fire on for, is a goddess or god who hasn’t submitted to our sanctimonies and sacraments, who hasn’t submitted to religion. And that’s Macha.

For Macha I leave my door open.

For Macha I leave my fire lighting at night.

Macha hasn’t been covered by culture.

Macha hasn’t been covered by religion.

Who or what could cover Macha? he asked.

You have covered Macha, she replied.

Outraged and afraid, he was on the floor pulling on his clothes and his boots.

Hearing her walk away, he looked up.

Hearing hooves on the yard, he went to the door.

It was May morning and Crunncu knew, too late he knew, that it wasn’t his neighbour’s nag who neighed from the hills.

OLLAMH FÓDHLA

As is the case with all other rivers, our river has its source in Nectan’s Well. And that is why we learn to speak. To learn to speak is to learn to say:

Our river has its source in an Otherworld well

and anything we say about the hills and anything we say about the stars is a way of saying.

A hazel grows over the Otherworld well our river has its source in.

Our time being so other than Otherworld time, it isn’t often, in our time, that a hazel nut falls into Nectan’s Well, but when it does it is carried downstream and if, passing from current to current, it is brought to your feet and you eat it, then though in no way altered, sight in you will be pure wonder. Then, seeing ordinary things in the ordinary way you had always seen them, sight in you will be more visionary than vision.

To know, and to continue to know, that any well we dip our buckets into is Nectan’s Well is why we are a people.

We are a river people.

Exile for us is to live in a house that isn’t river-mirrored.

Our river isn’t only a river. It is also the moon-white cow who will sometimes walk towards us, but not all the way towards us, on one or another of its banks.

The river and the cow we call by the same name. We call them Boann.

Boann, the moon-white cow.

Boann, the gleaming river.

In dreams I know it as cow.

Awake I know it as river.

And my house isn’t only river-mirrored. It is mirrored in Linn Feic, its most sacred pool. And this is so because, by difficult and resisted destiny, I am ollamh to my people. They call me Ollamh Fódhla. In their views of me, Boann, the gleaming river, has carried a hazel nut to my feet.

As these things often do, it began in sleep, in dreams in the night: standing in my door I’d be tempted to think he was only a short morning’s walk away, and yet it would often be nightfall before I’d at last turn back, not having made it. A sense I had is that the man I was seeking to reach was myself as I one day would be. In the most frightening of all the dreams I dreamed at that time a man who had no face came towards me and said, you are worlds away from him. When he next came towards me he had a face and he said, you are as far away from him as waking is from dreaming. In the end it was my own voice, more anguished than angry, that I heard: it isn’t distance, measurable in hours or days of walking, that separates you from what you would be. It is states of mind, yours more than his.

Defeated, I settled back into my old ways. At this time of year that meant that one morning I’d pull my door shut behind me and drive my cattle to the high grazing ground between the Paps of Morrigu.

My father who quoted his father had always assured me that there was no sacrilege in this. According to the oldest ancestor we had hearsay of, it was in no sense a right that we claimed. Fearfully, it was a seasonal rite we were called upon to undergo. This I took on trust, allowing that there was something more than good husbandry at stake.

Up here, summer after summer since I was a boy, we shook off the vexations and the weariness of winter enclosure.

Up here the gods were not fenced in.

Up here, when we heard him neighing, we knew that the horse god couldn’t be cut down to cult size, couldn’t be made to serve religious need. Up here there is a rock. It so challenges our sane sense of things that I long ago capitulated to the embarrassment of crediting what my father and his father before him used to say about it, that every seven years, at Samhain, it turns into an old woman driving a cow.

Sensing my difficulties, my father was blunt: if in the eyes of the world you aren’t embarrassed by your beliefs about the world then you may conclude that the wonder-eye which is in all of us hasn’t yet opened in you.

That’s how it was with me in those days. No sooner had I learned the world and learned my way in it than, standing in front of a rock or a tree, I’d have to unlearn it. I’d hear a story and think that’s it, that’s how the world is, that story will house me, but then there she’d be, the old woman driving her cow in through my front door and out through my back door, leaving me homeless yet again.

And it wasn’t just anywhere I was homeless. I was homeless on the high grazing ground between the Paps of Morrigu, and it wasn’t by hearsay that, however red-mouthed she was, Morrigu was divine, all the more divine in my eyes because, like the horse god who neighed only at night, she would never submit to religious servility. Though a people prayed to her she wouldn’t send rain in a time of drought or stand in battle with them against an invader.

Worship of Morrigu, of red-mouthed Morrigu, had to be pure.

And that’s what I did up here.

Up here every summer I lived between the breasts of a goddess who, in her form as scald crow, called above me everyday, circled and called, searching for afterbirths, searching for corpses, searching for carrion.

The contradiction ploughed me. It ploughed me and harrowed me. ’Twas as if the breasts of the mother goddess had become the Paps of the battle goddess. And to live between the Paps was to live in trepidation of the divine embrace.

Sometimes hearing her call as a scald crow calls I would hear a demand: you must be religious but in being religious you must have no recourse to religion.

So that is it, I thought. That is the seasonal rite. To be religious up here is to fast from religion.

These were heights I wasn’t continuously able for. Always by summer’s end I’d have lost my nerve, and now again I would pull a door shut behind me and I would go down, me and my cattle, my cattle going down to the shelter of the woods and swards along the river, and I going down to the shelter of traditional religion and story.

Here, as well as being a moon-white cow, the goddess is Boann, the gleaming river.

Down here, we are river-mirrored. And since it is the same sacred river that mirrors us, we are a people.

My house is mirrored in Linn Feic.

In a sense therefore I sleep in Linn Feic, I dream in Linn Feic.

At a sleeping depth of me that I’m not aware of, maybe I am a salmon in Linn Feic, and maybe I swim upstream every night, all the way up into the Otherworld, all the way up into Nectan’s Well. At that depth of myself, maybe the shadows of the Otherworld hazel are always upon me. Are always upon all of us, letting wisdom and wonder drop down into us.

Could it be that we are safer in our depths than we are in our heights? Or, could it be that we will only be safe in the heights when we already know that we are safe in our depths?

This time the old woman didn’t drive her cow through the conclusion I came to. This time, bringing a six years’ solitude in the Loughcrew hills to a sudden end, it was like a stroke, it was like waking up from waking. During an endless instant, all heights and depths had disappeared, leaving only a void, or what seemed like a void.

Twenty-six years later, sitting in my house by Linn Feic, I was able say, it is in Divine Ground behind all depths and heights that we are safe.