Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

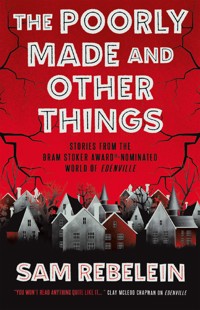

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

Goosebumps meets Stephen King at Edenville College, where an aspiring horror novelist takes a teaching job and soon finds a blood-soaked town history, a secret society in the library basement, alternate dimensions and people who might actually be spiders… When young horror writer Cam Marion is offered a teaching opportunity at a prestigious liberal arts college upstate, his long-time girlfriend Quinn is skeptical. She knows the college is located in Edenville, in infamous Renfield County. The county where people seem to go missing. The county where Quinn's high school best friend was mysteriously killed. Quinn figures the job opportunity is a trap somehow, so she follows Cam upstate to investigate some of the county's mysteries (including her own). She quickly discovers that there's an entire society dedicated to solving Renfield's many riddles. A society that puts on plays dedicated to Renfield's macabre, blood-soaked history. A society that meets in the library basement once a week. A society made up of people who might not be people at all....Meanwhile, Cam discovers that his newest story idea isn't an idea so much as it is a vision of another world. A world that the faculty at Edenville College need his help to access before it accesses them.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 524

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Map

Overture

The Gummerfolk

Act One

Chapter One The C.M. Box

Chapter Two The Red Yard

Chapter Three Sydney Kim

Chapter Four Reels You In

Chapter Five 1896 Netherwild Lane

Elsewhere

Act Two

Chapter Six Your Very Last Cigarette and A Trip to Pancake Planet

Chapter Seven The Library

Chapter Eight Sunflowers

Chapter Nine Cam Meets McCall

Chapter Ten The Edenville Players Present: No Longer Lawrence

Chapter Eleven A Tapestry of Gore

Elsewhere Deadman’s Well

Chapter Twelve Sundown

Chapter Thirteen Historical Society

Outside Lillian, March 1974

Act Three

Chapter Fourteen Auntie Ethel’s Eternity Trunk

Chapter Fifteen Shardsoap & Lady-Husks

Chapter Sixteen Wood Raid

Chapter Seventeen A Perfect Ecosystem

Chapter Eighteen SHE’s A Lady

Chapter Nineteen Gretamorphosis

Chapter Twenty Ichabod

Bent, April 2018

Act Four

Chapter Twenty-One The Old Biology Building

Chapter Twenty-Two “My Bedroom is Rotting”, By Benny Mccall (Clarity’s Story)

Chapter Twenty-Three Emergency Faculty Meeting

Chapter Twenty-Four The Mither Ruins

Chapter Twenty-Five Burn It To The Godforsaken Ground

Chapter Twenty-Six Fingers From The Other Side

Coda

A Road Outta Renfield

Acknowledgments

About the Author

“Edenville is pure cosmic gonzo... Thisjaw-dropping—apologies,jaw-ripping—novel earns its place amongst contemporary classics The Library at Mount Char and The Book of Accidents. You won’t read anything quite like it... not in our universe, anyway.”

CLAY MCLEOD CHAPMAN, author of Ghost Eaters

“There are many campus horror novels, but I think Edenville gets an A for AAAAAAIIIIIII! Sam Rebelein should be awarded a Masters Degree in SCARY. A major new talent!”

R.L. STINE, author of Goosebumps and Fear Street

“A mind-bending experience, Edenville is a transportive read that burrows down into the center of your mind and refuses to let go. There’s beauty and squick in these pages, and at its core, a whole lotta fun.”

KRISTI DEMEESTER, author of Such a Pretty Smile

“Nobody is writing the uncanny like Sam Rebelein. Edenville is an immersive, visceral, unsettling metafictional tale that lures you into the shadows, and then slowly expands your mind to the horrors that were always there. It’s Chuck Palahniuk mixed with Clive Barker and Stephen Graham Jones to create a funny, heartbreaking, original piece of fiction.”

RICHARD THOMAS, author of Spontaneous Human Combustion, a Bram Stoker® finalist

“In Edenville, there’s a captivating and equally irresistible kind of frenetic intensity pulsing from each and every page—the raw, powerful energy of a new, uninhibited talent in horror fiction. Sam Rebelein possesses the skillset of a venerated master and Edenville is a truly imaginative debut.”

ERIC LAROCCA, author of Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke

“Edenville is a delightfully gooey blend of gothic, cosmic, folk and body horror churned by a sharp-bladed critique of academia.”

LUCY A. SNYDER, Bram Stoker® Award-winning author of Sister, Maiden, Monster

“Edenville is a tour de force of horror writing. The eerie atmosphere and building intensity will have you on the edge of your seat, while the sharply drawn characters and nightmarish imagery will keep you hooked from start to finish. Fans of Clive Barker and Stephen King at the peak of their powers won’t want to miss this one.”

TIM WAGGONER, author of A Hunter Called Night

“Edenville reinvents the small-town scary story as an onslaught of comedy, horror, and grotesquerie. Great, blood-curdling fun.”

STEPHANIE FELDMAN, author of Saturnalia

“Edenville is brilliant. Edenville is hilarious. Its denizens are as charming as they are hideous. This is a thrilling horror story with glorious characters occupying a deliciously rendered world.”

CHRIS PANATIER, author of The Phlebotomist

“[D]ebut author Sam Rebelein satisfyingly combines scares with humor as a struggling author moves to the unsettling town of Edenville.”

LIBRARY JOURNAL

“The mundane horrors of rural and academic living collide with pure cosmic weirdness in Sam Rebelein’s Edenville. Not since Jason Pargin’s John Dies at the End have I been so horrified and grossed out by a book… I could say more, but honestly, the less you know about this book, the better. A fantastic debut.”

TODD KEISLING, Bram Stoker® Award-nominated author of Devil’s Creek and Cold, Black & Infinite

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Edenville

Print edition ISBN: 9781803364681

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803364698

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: October 2023

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Sam Rebelein 2023.

The right of Samuel Rebelein to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For all the amazing English teachers I’ve ever had:

Dan Jones, Sue Parise (a true angel), Ms. Roussin, Mr. Thell, Tracy, Kevin Lang, Kristine Jackson, Darcy Soi, Dan-the-Man Pitt!, Eric Buergers, Paul Russell, Jean Kane, Mark Amodio (who taught me to be tethered), David Means, Foster, David Tolley, Tyrone Simpson, Wendy Graham, Michael, Sherri!!, John (who embraced Renfield in its earliest form), and of course, a real hero: Darrah freakin Cloud.

Thank you all for helping me get here. None of you were monsters.

Affirmations help achieve a sense of safety and hope:I am a channel for God’s creativity, and my work comes to good.

JULIA CAMERON, The Artist’s Way

You can’t trust anybody in a goddam school.

HOLDEN CAULFIELD, in J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye

OVERTURE

THE GUMMERFOLK

He dreamt of an attic. Of course, it wasn’t a dream, per se. But Cam didn’t know that at the time.

The attic had a sharp-peaked roof, as if Cam were inside a perfectly triangular wooden prism. The point at the center of the ceiling ran from the stairs at one wall all the way to the small square window in the other. He wondered what the outside of the house looked like, if the roof was so sharp you could cut yourself along its edge.

The wood of the attic was unfinished, unsanded, splinterous, and rough. Nail ends jutted out all over. The room itself looked like a torture device. In its center was a faded pink sofa with wooden legs carved into human feet. The rest of the attic was bare.

Cam sat on the sofa’s middle cushion. He couldn’t move. Couldn’t blink. Across from him, about a foot off the floor, something was etched into the sloped wood of the wall. He managed to squint, and saw it was a man. Or . . . manlike. Minimalist, in thick, cakey yellow chalk. Two lines for legs, one down-swooping curve for each arm. And a ragged mass of spiked hair for the head. Someone had taken the chalk and scribbled it in an angry circle several times, digging in until the chalk cracked and caked in odd patterns. In the middle of this hair were two thick, slanted lines. Deep. Gouged hard into the wood.

The eyes hurt to look at. Like gazing into the sun.

Cam struggled to open his mouth, to speak, and as he did, the figure on the wall opened with him. The yellow chalk lines blurred. Beads of red popped like sweat from pores. Dark crimson fluid began to drain from the figure’s hair and eyes, to run across the floor in spidery tendrils, throbbing as they stretched in all directions. Fingers poked out between the boards of the attic wall. Dozens of black-clawed, gray-fleshed hands wrapped around the wood from the other side. Yellow eyes and puckered mouths, pressing up against the wall from within. Fingers yanking at the wood, trying to pull it apart, to pop loose all the boards upon which this figure was drawn.

The gummerfolk were coming through.

“Don’t,” Cam managed to say, the word molasses-ing out of him. “Dooon’t.”

But his voice was drowned by another. Someone he couldn’t see. Some booming, hell-thunder tone that read to him—the poem.

He’d remember it for the rest of his life, word for fuckin word:

The Shattered Man,with wild hair.You better run,avoid His stare.If you see Him,you are through.Cuz chances are?He alreadyhas seenyou.

On the final word, a board wrenched free with a snap. Fingers pulled it back into the darkness of the wall. And the gummerfolk began to slide into the attic.

If they had ever been human, they definitely weren’t now. Now they looked like someone had dug the bones out of regular people, held their skins to a flame, and watched them melt. Their shoulders oozed halfway down their sides. Arms bent out of their abdomens. Legs dribbled directly down from their ribs. Their heads rolled, sloshing against their chests. Their faces drooped and their waxy lips opened, closed, like fish on hooks, choking on air. Their clothes were all askew, simple T-shirts and denim jeans, on sidewise and janky. Their hair was tufts of brown wire plugged into the warm clay of their scalps. The gummerfolk, an abandoned project forgotten in the cellar of the universe, squeezed their way out of this bleeding hole, one at a time, and spread like multiplying cells, expanding through the attic. Wobbling and sloshing. Some poorly made cross between a man, a leech, and one of those slippery snake tube-toys you find at, like, Rainforest Cafe.

God gave up while making these.

“Doon’t,” said Cam, more strained this time, like shouting through mud.

So many of them pouring through the hole. Warbling and swaggering around the attic. Aimless—until their eyes landed on Cam.

The first oodled its way around the side of the sofa. Its arms dangled at its sides, one twisted to the front, the other wrenched behind its back. It opened its mouth and ran its bugged eyes (one falling far down its cheek) over the entire course of Cam’s body. He could feel the eyes like snakes upon his limbs, slithering up and down. Tasting him. The gummerthing made slobbery, licky noises. Wavering side to side.

Then fell on him.

It smacked its mouth against the side of Cam’s neck, the fleshy bit with lots of strings inside. And it began to chew. To gum, really, because it had no teeth. It gnawed at him, very slowly. And as it did, Cam realized its lips weren’t waxy, weak things at all. They had muscle behind them. They were strong. It’d take a while, yes, but this thing was going to gum him to death, no doubt about it. In a matter of maybe two or three agonizingly slow, gradually more painful hours, Cam was going to die at the hands of a toothless leech.

Another fell upon his ankle, splatting prostrate onto the floor. It moaned with pleasure, and its eyes rolled in opposite directions as it sucked at the side of Cam’s foot, just over the big knob of bone.

Another fell on Cam’s arm. Its mouth began to work at the flesh inside his elbow. Gums clenching, squeezing, releasing. He could feel tongues rolling over him. Warm, wet slobbering. Their jaws were strong, so strong. But he couldn’t move. Couldn’t fend them off.

Another gummerthing tripped over the one on the floor and fell into Cam’s lap. It made an audible, cartoonish amph! as it chomped down on Cam’s inner thigh. Another leapt over the back of the sofa, nuzzled Cam’s shirt off his belly, and latched on to his navel. He felt the gums working at his gut. Squeezing, releasing. Squeezing, sucking, releasing. Nudging around the organs inside.

Another fell on his bare toes.

Another swallowed his entire hand, knuckles grrrinding between its gums as its mouth squeeeezed . . .

At last, one of them waddled around behind him. He heard it crack open its mouth in a big, wet yawn. Drool dripped into his hair.

“Doon’t,” Cam moaned.

But the thing didn’t listen. Of course it didn’t. Why would it?

A great whoosh of air as it swooped down and took the crown of Cam’s head inside its jaw. It squeezed its gums around his skull and sucked. Some of Cam’s hair ripped loose, vacuumed away down its widening throat.

“Doon’t.” It slid its mouth lower. A snake shoving prey into itself. “Dooon’t.”

It worked its mouth down, lips wriggling over Cam’s eyes. He felt them squish back into his skull, the gums pressing, pressing. Everything went dark.

“Doooon’t.”

The mouth descended over his nostrils, practically breaking Cam’s nose up into his brain, grinding into the nape of his neck and his ears. All the while, more mouths fell on him, all over his body.

“Dooooon’t!” he cried as he sucked in air between his teeth. He took a big breath, and the thing swept its lip into his mouth, shoved his tongue back into his throat. It dug its own tongue into him, tasting him gag. It pulsed lower, mouth moving down over Cam’s chin, so that the suffocating, warm, wet flesh of its throat covered his entire face. He could taste its bile as it tasted him. Things in its jaw cracked as it widened, and prepared to take his shoulders.

Finally, the scream yawned from Cam’s chest in one big “DOOON’T!”

He was awake.

He lurched up in bed. The R train rumbled through Brooklyn’s underground, rattling the windows from far below. Lampposts poured a soft orange glow across the ceiling. Quinn snored gently at his side.

He was awake. And he was alive.

“Jesus,” he murmured. He took a shaky breath, rubbed at his eyes. Pain lashed through his skull. He grit his teeth, swore at the dim bedroom. He blinked hard, several times. He wasn’t crying. Something else was in his eyes. Something gluey? He held up his hand, pulled his fingers apart. Fluid separated between his knuckles in thick boogery strands. It was cold. Glacier-cold.

The fuck?

He blinked again, and the poem blared in his mind.

He scrabbled for his phone on the nightstand and typed it all out, though the screen was blurred, his fingers sticky, his eyes throbbing horribly.

He felt like if he didn’t write it down, he’d die.

The Shattered Man,with wild hair.You better run,avoid His stare.If you see Him,you are through.Cuz chances are?He alreadyhas seenyou.

* * *

“Ew, why would you have jizz in your eyes?” Quinn asked, brushing her teeth in the open doorway between their bedroom and the bathroom.

Cam, still in bed, stared at the ceiling with bloodshot eyes. “Well, it’s not snot. It’s . . . rubbery. And sort of white.”

“You save any of it?”

“God, no.”

Quinn grunted around her toothbrush.

“My hypothesis,” said Cam, in his I have an MFA, therefore am smart tone that Quinn used to love and now didn’t at all, “is that it was a wet dream in addition to being a nightmare. That happens, right? You get so spooked you . . . cream the bed? Somehow, I’ve spooked myself into ejaculating directly up the length of my body, into my eyes.” He cracked his knuckles, pleased with himself. “My aim must be pretty good.”

“Ha. It’s not.” Quinn spat toothpaste into the sink. “Besides, your briefs aren’t wet. Are they?”

“Hm. True. They are dry.” Cam picked at his beard, thinking, as Quinn smeared on deodorant.

“Maybe something dripped down from the third floor,” he said. “A leak or something?”

Quinn glanced at the ceiling. “Looks fine to me. You google it?”

“It’ll just tell me I have eye cancer or something.”

“And you don’t think you have eye cancer.”

“Well, I hope not.”

“Then you know the alternative.” Quinn cocked her head, let that dangle for a moment, like he was supposed to fill in the blank.

Cam held up his hands. “I . . . do have eye cancer?”

“Ahh. See, this is a perfect example of the rule.”

“What rule?”

“Our rule. If anything creepy happens in the apartment . . .”

Cam groaned and rolled his eyes, which stung. He squeezed them shut. “Of course. We call the super.”

Quinn had a Q-tip buried in her ear now. She nodded. “Because Diego said the building might be haunted. So if anything happens we can’t explain, we don’t be bullshit about it. Don’t say it’s the wind or some shit. Don’t say it’s an old building that leaks. It’s a fuckin ghost. If the question is, Is it a ghost? then it’s a goddamn ghost. We’ve both seen too many scary movies to be that kind of stupid.”

This was true. Ordering Indian food from the place down the block and watching bad horror movies was a favorite pastime of theirs. Cam claimed it was inspiration for his writing. But he’d left his laptop open the other day, and Quinn had snooped a little (how can you not?), and she’d discovered he hadn’t written anything new in months. He had been playing a lot of Skyrim, though. So that’s what he’d been doing while she was on the roof smoking cigarettes by herself, watching the traffic on the bridges to Manhattan, glittering in the murky night.

“So how are you applying the Diego Rule in this scenario?” Cam asked. “Did a ghost jerk off into my eyes?”

She sat on the edge of the bed, began to lace up her boots. “Who knows. Maybe you’re possessed. Maybe you came out of your own eyes. A braingasm!” She gasped, clutched his thigh. “New band name, I call it. Braingasm.” She went back to her boots. “Ya know, semen burns your eyes. Could be why they hurt.”

“Quinn, it’s not brain semen. How does that make more sense than—”

“It’s because your cornea’s made of the same cellular material eggs are made of? So the sperm just dig in there, thinking it’s—”

Cam buried his face in his hands. “Quinn, oh my god.”

She clapped her thighs, launched herself to her feet. “Look, I’m just sayin. If it smells creepy, it is creepy.”

“Well, just because the dude who sold us the apartment said it’s haunted doesn’t mean it is.”

A pang of betrayal needled up Quinn’s chest. “Cam, I’m ashamed of you, I really am. You’re mister big horror guy, and now you’re gonna say some dumb bull like, ‘Oh, the dude told us the apartment was haunted but I don’t believe him’?”

“But we’ve had no flickering lights, no . . . strangewhispers . . .”

“Baby, you’re a strange whisper.” She leaned over, kissed his forehead. Really dug her lips into him to blot her lipstick on his skin. When she released him, he had a bright red Fight Club–style mouth just over his third eye. He looked cute, all blear-eyed and snug in bed.

“I gotta go help Kenz with inventory,” she said. “I love you, have a good day, don’t get ghosted.”

And she was gone.

Cam washed his eyes in the sink for the third time that morning. But the water made the sting worse. He felt like he’d coated his eyes in some acidic plastic shell. When he rubbed at them, they seemed to shift around inside his skull.

He sat at the little desk in their bedroom, opened his laptop. He eyed the Skyrim icon. Last time he’d played, the game claimed he’d logged over a thousand hours. That . . . didn’t seem very healthy.

So he cracked his knuckles. Opened a fresh Word doc. Picked at his beard. Stared at the blinking cursor. Rubbed his eyes.

And began to write.

The words came easily, for once. He found himself writing about the house under the attic from his dream. The man who lived there, one Frank LaMorte, had annihilated his family with a box cutter. All four of his children, peeled like bananas. When he was done, he took great dripping handfuls of them and painted a stick figure on the attic wall. An act so cruel and bizarre, it changed those wooden boards forever, warping them into a doorway to a nightmare realm. When the boards were pulled apart, the house painted over and thrown back onto the market, that blood-figure man was scattered into pieces, the doorway from His realm to ours—broken once more. He became angry. He became the Shattered Man.

This was the best work Cam had ever done.

But as he wrote, the burn behind his eyes grew worse. He could barely see the screen, his vision was so bad. Fat drops of cold phlegm curdled out of his eyes and spattered onto the backs of his hands as he wrote, and wrote, and wrote. He followed the story as it twisted in new directions, moving of its own accord. He’d always heard stories do that, but he’d never seen it firsthand. It was strange. Something was curling out of him, stinging his eyes as it needled its way out of its nest in his brain.

Weeks of this.

Quinn asked if he wanted to see a doctor. No, a doctor might cure it, and curing it might dry up the words. Cam adamantly refused, blinking and bloodshot.

Four months later, he had himself a novel. And as suddenly as it’d begun, the burning in his eyes? Gone, without a trace.

See? No doctor necessary.

Cam had exactly three publishing credits to his name before The Shattered Man. Three stories in semi-pro magazines that he should’ve been proud of but wasn’t. But he felt, finally, that Shattered Man was something important. At last, he’d written something that mattered. An entire novel! He just knew it was going to change his life.

Ohh yes. It would change his life indeed.

* * *

That was three years ago. Back when Cam and Quinn had first gotten their together-apartment, in Park Slope. Quinn liked the place because it got morning sun, and their windows opened onto the building’s courtyard, full of actual trees. She loved that she could fall asleep to the sound of wind in leaves, instead of the trucks and drunks along 4th Ave. She could walk along the entire roof, too, all around the building. She could see the Statue of Liberty, the far-off shimmer of the Chrysler Building . . . Cam spent his evenings bolted to his desk, so Quinn got used to coming up on the roof by herself, with a cigarette and her father’s lighter, the Zippo with Marilyn Monroe etched in its side in Warhol colors. She’d put her Spotify on shuffle, stick in her earbuds, and watch the red and white lights tinkling in the polluted dark of the city.

Quinn was comfortable being alone.

Cam didn’t mind the sound of traffic at night. But he wasn’t born and raised upstate like Quinn. His parents worked at NYU. He didn’t know the music of peeper-frogs, trains howling at night through the woods. He’d gone north for his MFA at Branson College, in the mostly-nothing town of Furrowkill. There, he met Quinn (a junior and a theater major at the time). She’d clung to him because he talked about himself like he was important. Quinn felt like river debris at best, bobbing along through life without any direction except down. After they both graduated, he asked if she wanted to follow him back to the city.

“Cam, my hometown has only five thousand people,” she’d told him. “We used to have a bowling alley, and we used to have a Blockbuster. I’m from Leaden Hollow.” Grimacing like the name tasted how it sounded. “So yeah. I would love to move to Brooklyn with you. I could get involved in theater! Be in weird plays in black boxes downtown.” Which she never really ended up doing (the “weird plays” she auditioned for always seemed to require more nude monologuing and rolling around in milk than she was comfortable with), but it’d been a nice dream to cling to when she’d said goodbye to Leaden Hollow.

Quinn was done with Leaden Hollow anyway. Everywhere she went, she felt like she was kicking up a slow-growing layer of water and sediment. Like the place was gradually flooding itself with memory, as most small towns do. Cam was just an easy buoy to cling to as she floated away from home. She hated herself for those moments alone on the Brooklyn roof, when she yearned to go back.

Such a dirty fuckin trick hometowns play. You can’t wait to leave. Then they keep whispering your name on the wind.

They’d been dating for two years already when Cam had the attic nightmare. Quinn was so relieved. Cam had spent their first year in the city getting high and playing Witcher 3, sitting around saying “Roach!” in that white-haired dude’s gravelly voice. Picking at his beard on the couch, leaving coarse little hairs all over the floor. He’d smoke an entire joint, ramble at Quinn about how he could be the next Stephen King, then turn on the PlayStation. Again.

But the nightmare seemed to give him a new sense of purpose. Then he managed to sell the book to a small indie press—some bunch of nerds operating out of a refurbished cider mill in Vermont. Quinn had been stoked. Cam was invited to readings; he did interviews. It wasn’t a big splash, but it made him happy.

Except Happy Cam was somehow even more smug and irritating than Unhappy Cam. Happy Cam berated Quinn for her taste in food, her music. He was now officially better than her, a successful novelist. And it stung. Especially when she pulled back from theater altogether, and became just another Brooklyn bartender with an abandoned dream.

When the indie press tanked, dragging Shattered Man down with it, Unhappy Cam reemerged, and Quinn remembered she didn’t like him very much either. He was bitter and cynical. Had zero ideas for future books. He slumped around the city for his tutoring job that he hated, grumbling about the SATs and ungrateful high schoolers. Schlepping brick-size test-prep books from apartment to apartment, having all these one-on-one sessions with sixteen-year-olds who couldn’t give a fuck, then coming home and demanding Quinn rub his shoulders as he rolled a joint.

Rinse and repeat.

She watched him sink into an irrevocable bitterness. This thing he’d believed would change his life hadn’t changed anything at all. He was just as unimportant as he’d always been. He hadn’t even written a word since that last cold tear dried up on his keyboard.

Quinn felt she could relate. Turns out, she didn’t want to grind through audition after audition. Kicking herself, for example, for missing an open call just because someone threw themselves onto the tracks of the F train up ahead. Sitting there sweating in the piss-stink of the subway car, clutching her old headshot, picturing the corpse-cleaners a mile up the track. Fuckin horrible. And she finally had to admit to herself that theater had never been that fun anyway, even in college, without Celeste. Celeste was the one who’d gotten her into acting in the first place. Back in the day.

So then . . . whatdid Quinn wanna do?

Good question.

Over time, Unhappy Cam became somehow . . . comforting. At least rubbing his shoulders gave her something to do. Lines to recite.

“It’s okay, baby,” Quinn told him, time and again as she dug into his muscles, staring over his head at Witcher 3. “You’ll write something huge one day. I know you will. I know it . . .”

Hoping desperately that this was true.

ACT ONE

SHATTERED MAN, WITH WILD HAIR

When Caleb Wentley discovers a small stick figure drawn in chalk on his attic wall, he doesn’t think much about it. It’s just a yellow set of lines with a weird mess of hair and two diagonal slits for eyes. Creepy, but the previous tenants had kids, didn’t they? Kids draw on walls.

But when something starts to whisper to him through the chalk—digging its fingers between the wooden slats of the wall and pressing its mouth against the wood from the other side—Caleb knows something is wrong.

His investigation into the history of the house leads him to a cult-like organization called the Committee for the Reconstruction of the Shattered Man. The Committee tells Caleb that the figure in his attic is only a scale drawing of a much larger design. Thirty years ago, the Shattered Man, a god-like giant from another plane, was summoned in blood, across an entire wall of what is now Caleb’s attic. The boards He was splashed across have been scattered around the country (macabre keepsakes for true crime fans), but the Committee is almost done recollecting them. They just need Caleb’s help finding one last piece. Once that’s in place, and the Shattered Man is whole again, He will open a doorway to a world far more monstrous than our own . . .

In Campbell P. Marion’s debut horror novel, The Shattered Man, Caleb must race against time to stop the Committee from opening this door, before the creatures on the other side pry their way through. It isn’t long before Caleb learns the Committee’s ultimate plan for him, and the most important lesson about the Shattered Man: Once He’s whole, only fresh death can unlock His favor.

Jacket copy from the back cover ofThe Shattered Man

CHAPTER ONE

THE C.M. BOX

The lounge dedicated to the faculty of the Creative Writing department is not very large. But then again, neither is the Creative Writing department. Madeline Narrows was one of only ten professors.

She sat on the green leather couch facing the mantel in the lounge, her bare feet propped up on the coffee table before her. Madeline liked to be barefoot. It helped her feel the breath of the Earth, she thought.

She closed the book she’d been reading. Its spine crinkled gently in the silence of the lounge. She ran her hands over its surface. The Shattered Man bled across its cover in bold, chalky yellow letters. The stick figure with its spiky hair and eerie eyes stared up at her, made her shiver.

Madeline didn’t know this writer, this Campbell P. Marion. According to his bio on the book’s back cover, this was his first book. He was a young white man with a thick beard and round glasses. He had an MFA from Branson College, about an hour’s drive from where Madeline now sat. He wasn’t smiling in his black-and-white photo, which was credited to a Quinn Rose Carver-Dobson. What a nice name. It sounded like a law firm. Madeline wondered what their relationship was.

When she ran her fingers over the image of Campbell’s face, she felt that he was kind, but that he often chose not to be. She felt that he could be selfish and small, but that he was well-loved by at least one person who believed in him (Quinn?). She felt that he could say mean things very easily, and that his ideas could be dangerous.

Madeline took her fingers away from him. They felt oily and tingly as she rubbed them together, the way they always did when Madeline felt things about people.

She’d enjoyed The Shattered Man tremendously. She’d read it in one sitting, in fact. But of course, she’d been riveted because the book had partially been about her.

See, every other week for the past three months, the department’s student employee (the sophomore boy with the gauges and blue hair) delivered a box to the department’s office. This box contained an embarrassingly large assortment of work. Books, magazines, printouts of online publications, newspapers, literary journals . . . All of it dumped into a waterlogged HelloFresh box and delivered from the campus library (where the blue-haired boy spent countless hours poring over archives, digital and physical) to the Creative Writing department in Slitter Hall. The boy didn’t know what it was all for, and thankfully, he never asked. Madeline didn’t know how they’d explain it to him. Where would she even begin?

At the Alumni House dinner in February (almost three months ago now), Madeline’s boyfriend, the handsome and award-winning writer Benny McCall, had gathered all ten Writing professors in a side room of the Alumni House. He poured himself a drink, told them to make themselves comfortable. And he told them a story that only three of the ten people in the room had believed. These three took turns reading the boxes every month. Digging through everything they could find by authors who all shared the same initials. The other seven professors didn’t speak to them much anymore.

Madeline hadn’t been as surprised by Benny’s story as the others had been. They’d been dating for three years before he arrived at the college this semester. The concept of having a boyfriend at forty-five, with one divorce under her belt already, still made Madeline giddy. But he’d felt . . . different this last year. She’d felt him in his sleep. Wormy was the word that came to mind, though she didn’t know why. He’d just been acting so strange since he won that fancy literary award last spring. Since he met that woman Catherine Mason. He’d been so . . . aloof.

So actually, she’d been relieved when he gathered them all in that room in the Alumni House, and told them what he knew. See? she’d thought. I knew it. He isn’t himself. It’d given her hope that things might get better. And when he asked this sub-department (those three people who’d believed) to begin organizing and sifting through the boxes—when he asked them to build those machines in the basement—Madeline had readily agreed.

It’s difficult to cut things off, especially when your boyfriend is such a fine kisser, and such a wonderful writer.

But reading through the boxes was a laborious, horrible task, with very few exceptions. Because Madeline knew that if she found anything worthwhile, she’d have to report it. And if she did that, it . . . essentially meant death to whomever she’d just read.

Which was why she was sitting here with The Shattered Man in silence, not moving. She wasn’t sure Campbell P. Marion deserved to die.

She laid the book in her lap, front cover up so she didn’t have to feel Campbell’s eyes on her, staring out from his author photo on the back. She looked up at the wide portrait adorning the wall above the mantel. She picked at her cuticles.

“Damn you,” she told the portrait.

The portrait did not respond.

* * *

Matthew Slitter, subject of this portrait, was college president from 1971 until ’79. He was widely considered an ineffectual, limp-handshake, hippie kind of man. Absent-minded and unfocused. He had tanned, leathery skin, absolutely no hair except the thin crown of wispy long white around the base of his skull. He wore round, wireframe bottle-lenses and blinked constantly, his eyes often red during college functions. His manner of speaking was distracted and whispery. He even carried around a froofy wooden cane like some mock Wonka. And he had this unclean smell about him, like sex or musk or weed.

In other words, he seemed pretty much constantly stoned.

But in 1973, Slitter observed something gravely important: a large number of English Literature & Linguistics students were submitting creative projects for their senior theses. When he inquired around the department as to why this was, Slitter learned that many of these students had just come home from Vietnam. Many more had lost friends, brothers, fathers . . .

Slitter drafted a college-wide memo, dated November 1973: “The human heart is too finicky and fragile to contain horror for long. It has too many chambers, too many holes. Material willleak out eventually, one way or another. You must express and exorcise, for without an outlet, a tributary, your heart will simply pour out inside yourself, until you’re full to bursting. You can die that way. Slowly, over the course of decades.

“So, hell. Let the people write.”

Slitter split the English department in two. The Creative Writers remained in Boldiven Hall, which Slitter renamed after himself (why not?). And all the Literature & Linguistics folks moved into new offices in Von Eichmann, the building kitty-corner to now–Slitter Hall. That didn’t particularly please the History professors, who’d had Von Eichmann to themselves, but Slitter built a new wing off Von’s east end, and the History department grumbled itself into a contented silence.

Slitter Hall was now home to four Writing professors, as well as the entirety of the Philosophy department, upstairs. The building’s old auditorium was remodeled, and Slitter instituted biweekly coffeehouse evenings there, where students and teachers alike could come to read their work. For students, it was an opportunity to share the writing they’d kept sacred throughout high school, many of them reading in public for the first time, hoping to maybe get a pat on the back from a beloved professor. For the faculty, it was, honestly, a chance to steal ideas for their own writing. It wasn’t like all of these kids were going to publish their shit anyway, right?

Soon, students in other departments began to participate in the coffeehouse as well, both as audience members and as writers, sharing poems, stories, songs. It didn’t hurt that Slitter insisted there be a spread of coffee and treats each week, all organized by his wife, Belinda. Thanks to Belinda, there was always a glut of chocolate chip cookies, brownies, and oatmeal raisin balls that even the most steadfast oatmeal-haters agreed were quite good.

So it was that the Slitter Coffeehouse Reading Series became a well-appreciated tradition at Edenville College. It showed up on college pamphlets. Slitter Auditorium became a major stop on the college tour. By 1985, the Creative Writing faculty had more than doubled. It became a popular inside joke: “Your kid’s a writer? My condolences. Well, send em off to Edenville.”

But despite this well-appreciated addition to campus life, Slitter’s inevitable forced retirement began in late 1978, when he used the phrase “far out” in another college-wide memo. Alumni worried he might try to turn the college into a commune. It didn’t help that he also wasted a fair amount of the college’s endowment on “whimsical” projects (and that’s cited from a letter to Slitter strongly suggesting that “retirement would probably suit you significantly better than academic life . . . Don’t you think?” The last few words of which were heavily underlined.). Matthew Slitter had no defense to this, and quite honestly, he was ready to go himself. If the board had no taste for his “whimsical” endeavors—such as ensuring there were more sunflowers on campus (an act that had also admittedly carried to Edenville a slew of aphids, beetles, midges, and moths), or instating Turtle Tuesday once a semester, in celebration of the snapping turtles in the campus lake—then Slitter simply “didn’t want to play anymore,” as he wrote in his letter back to the board.

It was, suffice it to say, a seamless and amicable transition.

In 1990, Matthew Slitter famously vanished, at eighty years old. There were rumors he’d been killed, his body fertilizer for the vast seas of sunflowers now covering the entire western academic lawn (West Campus for short, West Camp for shorter). Slitter’s flowers surround the borders of the campus as well, blocking it from view from the road. According to some, Matthew and Belinda (who vanished alongside her husband) are buried somewhere under campus, wrapped up in all those flower roots. And even in this strange new grave-life, motionless in the dirt, roots growing from his eyes, Slitter holds his wooden cane tight to his chest . . .

The point is, it was Matthew Slitter’s fault there was a Creative Writing department at all. Which meant, through a long series of accidents and coincidences and just plain bad luck, it was his fault that Professor Madeline Narrows was sitting here today, in Slitter Lounge, holding a stranger’s life in her hands.

* * *

“Damn you,” she told his portrait. The old president stood with his chest puffed high, in a field of sunflowers with his ever-faithful eagle-headed cane. Storm clouds brewed above him, lightning frozen midflicker on his glasses. Yellow petals swirled about his feet. He looked very grand and autumnal.

Madeline looked down at The Shattered Man again and sighed. Maybe she could pretend she never saw it. Drop it in the donation slot at the Edenville Public Library downtown. Or even better, rip its spine in half and stick it in the shredder. Maybe Benny would never know.

No. He’d know.

She glanced out the door behind her, into the hall. The couch had its back to most of the lounge, including the bookshelves, the big wooden conference table with its green banker’s lamps, the bar cart, and the door.

Nothing moved.

But even if he wasn’t watching her right now, he’d know. And he’d be pissed.

Madeline slipped into her Birkenstocks, rose from the couch, and tucked the book under her arm. She walked out of the lounge, past the window to the administrative assistant’s desk. Angie was in her late sixties. She had thick white hair compared to Madeline’s mousy brown, and her skin was a rich near-onyx compared to Madeline’s clouded blue-vein quartz. Twelve penguin bobbleheads nodded uniformly on her desk. She pointed at the book under Madeline’s arm. “Find anything good?”

“Hope so,” said Madeline brightly.

“Ohh exciting. He told me y’all are close to finishing.”

“Yep,” said Madeline, a little less brightly. “We are indeed . . .”

As she walked down the windowless length of Slitter Hall, Madeline passed rooms full of students, all in their last week of classes before finals. Slitter is academically and literally a stuffy building, especially in this last week of April, so the doors to these rooms were open, letting in some slightly fresher air from the hall. She glanced in one room to see Syd teaching her class on short fiction. She paced the room like a caged cat as she croaked on about “Gardner’s idea of the fictive dream, which will be on the final.”

Madeline lifted her hand in greeting. Syd nodded coolly at her. Once, perfunctory. The way Syd always nodded. Then she pointed at the chalkboard with the one arm that ended abruptly above her wrist. “So let’s start with this paragraph here.”

Madeline passed another room where Chett, hunched and nasally, was asking “literally anyone” to give him their opinion on Woolf’s use of free indirect discourse.

“Is Mr. Ramsay thinking this,” he droned, “or the authorial narrator? See, that’s the beauty of Deleuzian narratology.” Clicking his pen. “We get to really dig into these questions . . .”

Chett wasn’t in the sub-department. He wasn’t a believer.

At the end of the hall, Madeline turned toward the stairs. She took them down from the first floor to the basement. Then one flight further, to a door she had to unlock with a special key. As she did, the sounds of muffled machinery rolled over her. Music, too. Tom Jones, wailing on and on about his Delilah, that cheating backstabber who’d laughed when he confronted her. A grinding, crunching song that made Madeline wince.

But Wes loved Tom Jones. The music meant he was here.

Good.

She adjusted her grip on the book as she walked down the dim, flickering hall of the under-basement. Hot down here. Metal hot. She could taste gear grease on her tongue. As she walked deeper, it grew hotter. “Delilah” grew louder. Jones cried why over and over, drawing Madeline helplessly toward the pounding of the machines.

When she came to the great vault door, she rang the buzzer. A pause, and the door began to crank and grind. She listened to its bolts and bars churn themselves out of the wall. The door screamed open in a hellish, rusted whine—and there stood Professor Wes Flannery, in an apron spattered with blood.

“What?” he said. Behind him, the room groaned with engines. They cranked and banged, and Wes had to shout over their steamy clangor, over the music he had playing on his Bluetooth speaker resting on the metal sink bolted to the wall.

“It’s the middle of the day,” he said. “There’s students around.” Benny and Wes had laboriously soundproofed the under-basement, but . . . Murphy’s Law and all.

“I think I have someone!” Madeline shouted. She held out the book.

He took it in one big leather-gloved hand. He turned it over, glanced at both covers.

Wes was a pirate captain of a man. Broad and burly, six and a half feet tall. Hairy arms, deeply tanned and thick. The book looked much smaller in his hands than in Madeline’s. He towered over her with his electric-white hair, his old barfight scars. The apron, covered in stains. He was her oldest friend in the department. She was not afraid of him. And when he worked down here, his sweaty musk was not altogether unpleasant.

He handed the book back to her. “What’s in it?”

“The giant. The tapestry. Us, sort of.” She held it to her chest. “Can I come in?”

He stood aside.

Calling it a “room” would be generous. It was a massive concrete block, barren except for the metal slab in the center, the sink, and the massive twin turbines along the back wall, rotating endlessly. Madeline kept her eyes on the floor, avoided looking at the turbines. It was Wes’s job to take care of them. He’d traded that for having to take a turn reading the box. Madeline wondered if he still thought it was worth it. She hadn’t worked up the courage to touch him, to see what he felt like these days.

“The shelves are full,” he told her, turning down the volume on Jones. “That girl was the last. We’d have to recycle.”

“We’re still getting boxes, though.”

“Then take it up with your boyfriend, Benny. We’re outta room. Tell him not to be greedy.”

Madeline sputtered. “I . . . I’m not telling him that.”

Wes hawked a glob of phlegm onto the floor, by a metal drain. “So what do you want me to do?”

“Well, I haven’t . . . found anyone before,” said Madeline. “And I’m . . .”

“You’re having doubts.”

She paused. “Maybe.”

“So what, you want me to help you hide this?” Nodding at the book. “From McCall?”

“No.” She felt a lurch of fear.

“Then what do you want me to do?” Wes asked gently.

“I don’t know,” she snapped. She glanced at the large, clanking machine. “I just . . . It just really struck me that . . . We’rehurting people, Wes. That doesn’t bother you? At all?”

He was about to answer when a large cough caught him by surprise. It cracked his body in half. He racked up several wet coughs in a row, then spat again onto the floor.

“Ya know,” he sniffed, “maybe one day it will? But this is borrowed time, Madeline. If there’s even a chance . . .”

“I get it,” she said, not looking at him. Looking instead at the thing he’d just coughed up. It was blue, and reeked of juniper. She swallowed a small lump of bile. “I just don’t want to . . . hurt anyone anymore. I feel . . . stuck, Wes.”

He sighed. “Here.” Held his hand out for the book. Examined it again. Then: “Okay, here’s an idea. Maybe we can just . . . bring him in. Keep an eye on him.”

Madeline brightened. “He has an MFA. We could hire him!”

Wes nodded, reading Campbell’s bio. “Yeah, he’s got some credits . . . Why not ask him to be the next writer in residence? Next semester.”

“What about that other woman? The, the . . . playwright lady.”

Wes shrugged. “Fuck her. A sudden shift in schedule. She can come in the spring.”

“What if he doesn’t accept our invitation?”

Wes scoffed, handed her back the book. “He’ll accept. Because we can offer him what all young writers want.”

“Strippers and coke?”

He laughed. “Right. No, we can offer the poor asshole a chance at being important. What writer doesn’t want that?”

Madeline nodded, thinking. “Okay. Sure. Yeah, I’ll ask Ben tonight. Thank you.”

“Just don’t tell him it was my idea.” Wes turned from her, ripped off his gloves, began to wash his hands at the sink.

Madeline watched the shelves of the turbines revolve. She wiped sweat from her forehead. It was hot in here, so hot. And the only relief? A barely noticeable breeze from the large dented metal fan whooshing slow overhead.

“Where’s the girl?” she asked.

Wes flicked water off his hands, jerked his chin at the lefthand turbine. He led Madeline to it, and waited until one shelf in particular rotated around the bottom of the machine. He pressed a button. The engine jerked to a halt. Steam hissed. The shelf hung at chest height.

The girl had short red hair. She wore a beige bra, a diaper, and nothing more.

Madeline ran her finger up her arm. The girl twitched. Madeline tasted her pain. The bottomless, rusted dark. And she took it. Not all, just . . . a little. Let it soak up through her fingers. Felt it settle into her tissue, her bones.

“There,” she whispered. “It’s alright. Shhh . . .”

As the hurt crawled into her body, sucking at her marrow, Madeline grew a little thinner, thinner, until Wes said, “That’s enough.” He slammed the button, the engine whirred back to life, and the girl’s shelf swung up away from Madeline’s grasp.

“You’ll kill yourself doing that,” said Wes. He coughed. “You know that.”

“Has she dreamt of any wood yet?” Madeline asked.

“My guess is no. But you’ll have to ask Benny. He drinks the stuff.” Nodding at the tanks behind the machine. “He’d know.”

Madeline didn’t want to ask Benny. She hugged The Shattered Man tight to her chest.

Far overhead, the large metal fan . . . whooshed . . .

A vulture, circling its dying prey.

CHAPTER TWO

THE RED YARD

The Red Yard was an old bar. It smelled like old bar. Stale beer, ancient sweat, rancid lemons. The booth benches were plywood, the tables some kind of soggy sticky oak, pockmarked with decades of carved names and initials and dicks. The kind of place that might catch you alone, whisper drunk into your ear, a totally sloshed wallpaper arm sloughing off the wall and slinging across your shoulders, Hey man, lemme tellyasomethin . . .

The Red Yard had seen some fucked-up shit.

It’d first been built as a home for one Simon Routhier, meatpacker and friend of the Rockefellers. A thank-you for something history seems to have neglected to record. The beer garden behind the Red Yard was once an actual garden, filled with flowers, koi, butterflies . . . About a hundred years ago, Simon Routhier had been found in that garden, butchered beyond belief. Steaming globs of him spread across the entire space, dangling off the trees, oozing into the fishpond. Like he’d sneezed and suddenly exploded, leaving behind a big red yard.

Simon’s fresh twenty-year-old wife, Florence, was arrested at a speakeasy in Manhattan. They asked her why, of course. Was he having an affair? Did he smack her around? Why did she kill successful meatpacker Simon Routhier, her husband of only seven months?

Florence laughed. According to the Times, she laughed all the way to the chair.

Whenever Quinn worked in the Red Yard (most weekday nights), she found herself scanning the small crowds, all the awkward Hinge dates, for telltale signs of something otherworldly and cool. Translucent skin, old pucker scars on the neck . . . It just felt like the kind of bar vampires might meet in. When she handed people their beer, she always grazed their fingertips with her own. So far, every hand Quinn had touched here had been disappointingly warm. But she held out hope for evidence of something . . . somethingnew.

Doesn’t everyone.

Cam had once pointed out, annoyingly, that real-life vampires (“Well, if they exist”) might not follow the same rules as their mythic counterparts. Besides, Quinn was fairly vampiric herself. The pale skin, the bright, hypnotic eyes. And her hands were often quite cold, all skeletal and reddish.

Celeste used to call them witch’s hands. From any other mouth, that would sound like an insult. But Celeste had a way of making it sound spooky and powerful. I can just see those fingers cackling over a boiling pot of green, Quinn remembered her saying, in that smoky voice of hers. And You just have such pretty hands, her voice even smokier than usual. Tangling her fingers in Quinn’s, that night after homecoming. That awkward night when they were almost more than friends. The night they never got the chance to talk about, before . . .

Well. She didn’t need to think about that.

Florence Routhier’s picture hung on the wall by the little stage in the corner of the Red Yard, across from the bar, and directly over the dark hall leading back to the bathrooms. The picture had been taken three weeks before Florence burst her husband. She glared out of it with dead sepia eyes, a pinched black-lipstick mouth.

This picture was one of the main reasons Quinn liked working at Red Yard. Florence watched over all. The bar’s guardian angel was a legit murderer. Which meant, if anyone tried to fuck with Quinn or the bar or anything at all, Florence could be trusted to intervene. Quinn could feel her lurking in the floorboards. Somewhere under that old bar smell, there still lingered a hint of meat upon the air.

Quinn found it comforting. She lifted a glass to Flo, saluted her, and drank a sip of cider.

She stood behind the bar, earbud jammed in one ear: Iron & Wine’s cover of “Such Great Heights.” Real sad-girl shit she couldn’t play over the speakers because it’d bum everyone out. She had both hands in the kangaroo pouch of her hoodie, fidgeting with her dad’s old Marilyn lighter. She’d found that the more solid she made herself, the less likely she was to be hit on. Black boots, loose torn jeans, her old autumn-hued Leaden Hollow High hoodie (go Crows). It was yellow, orange, and brown, the colors of fall leaves. A crow soared across the front. It always made Quinn think of the old fight song: Go Leaden Hollow Crows! We’ll peck you dead, everybody knows! She wore her sharp bangs low over her eyes, so they twitched whenever she blinked. She’d seen someone do that in a movie once when she was eight, and it’d stuck, the way movie-things will when you are eight.

It was mind-boggling how many men acted like they were somehow the first to ever hit on her, to tell her she had pretty eyes.

“Wow thank you,” she’d started saying. “I have literally never been complimented before.”

Then again, she did have nice eyes, if she said so herself. Gray and ringed, like an old tree. Cam called them oaken eyes—betrayers of an old soul. She liked that. It was better than a lot of what she got at the bar, and she clung to it, deep in her heart. Just as she clung to the hoodie, which had once been Celeste’s. Celeste was a size fourteen, and the folds of fabric hung loose about Quinn’s body. Like a blanket she could walk around in.

She watched as the Red Yard filled slowly with patrons, the rickety tables in the middle of the floor beginning to creak with bodies, all filing in for the Red Yard Reading Series, which started in about ten minutes. Quinn eyed them all with distaste. She tried to see if she could explode any of them with her mind, like Florence Routhier had maybe once done. She squinted at them. They refused to explode.

Bummer.

The Series hosted three fantasy/sci-fi/horror authors, who read twenty minutes apiece, every other week. It’d begun long before Quinn started working at the bar, and if she’d known about it when she’d started, she probably wouldn’t have accepted the job. Because of course, it wasn’t long before Cam pulled the ole, “Any chance you could ask if I could read?” And of course, the woman running the series had loved him so much (Cam could really turn on the schmooze when he wanted to) that he was now a regular. But Cam never read anything new because he never wrote anything new, so every few months, Quinn had to listen to him read the same stupid pages from Shattered Man again. At this point, she could almost recite the story word for word: Frankie LaMorte hears a man’s voice behind the wall of his attic. He boxcuts his family to bits on its behalf, then paints a sketch of the Man on the wall in their blood. These slats of bloodstained wood are now cursed! They mutate you whenever you touch them, they’re sooo evil. If you have just one piece of the Shattered Man in your possession, you’re always wondering if your actions are yours—or His. And if you put Him all back together again, look out! Monsters will claw through the wood from another world.

Whatever. She didn’t need to hear all that spoooky nonsense again. She liked the book, but not that much. Not that she would ever say that.

She eyed Cam across the bar. The two other authors reading that night sat at one booth, but Cam sat, unsocial, in the corner. He picked at his beard, muttering to himself over a beer, reading through his pages for that evening. So nervous and tight-wound.

She watched him.

He did not explode.

Nothing in Quinn’s life exploded when she asked it to.

She’d put five years into this relationship now. Most of her twenties. Her youth! She couldn’t just cold-turkey it. She couldn’t cold-turkey anything. How many packs of menthols had she crushed up halfway through, thrown into the trash, and stood over like a grizzled assassin above the grave of a nemesis? That’ll be the very last cigarette I ever smoke, she’d vow solemnly every time. And then she’d buy a new pack, just a few months later, do it all again. If she broke up with Cam, who’s to say she wouldn’t just . . . buy another pack? So to speak.

And Crows forbid she give her mom the satisfaction of knowing she was right. Yes, Quinn had hopelessly entangled herself with “yet another artist boy adult man,” as her mother had called him last Christmas, after about half a bottle of Barefoot rosé. Quinn had done the same thing with that music major her freshman year at Branson. And the same thing twice during her senior year of high school. She’d fall for the hairy, tired-looking artist type. She’d push to make the relationship function. And the guy wouldn’t even care. Scraps of validation, few and far between.

“You’re jjust gonna keep doin the saame asshole,” her mother slurred. “Ssmoking the ssame shit. Dead girl walkin! Usin a dead man’s lighter. Shoulda left it in his coffin like he asked.”

That’d sent a cold shiver down Quinn’s spine. To be fair, Dad had asked to be buried with his lighter. It’d been his