Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The O'Brien Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: 16Lives

- Sprache: Englisch

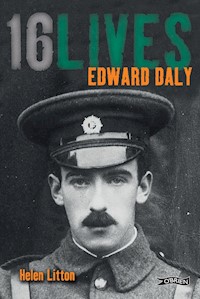

Born in Limerick in 1891, John Edward or 'Ned' Daly was the only son in a family of nine. Ned's father, Edward, an ardent Fenian, died before his son was born, but Ned's Uncle John, also a radical Fenian, was a formative influence. John Daly was prepared to use physical force to win Ireland's freedom and was imprisoned for twelve years for his activities. Ned's sister Kathleen married Tom Clarke, a key figure of the Easter Rising. Nationalism was in the Daly blood. Yet young Ned was seen as frivolous and unmotivated, interested only in his appearance and his social life. How Edward Daly became a professional Volunteer soldier, dedicated to freeing his country from foreign rule, forms the core of this biography. Drawing on family memories and archives, Edward Daly's grandniece Helen Litton uncovers the untold story of Edward Daly, providing an insight into one of the more enigmatic figures of the Easter Rising. As commandant during the Rising, Ned controlled the Four Courts area. On 4 May 1916, Commandant Edward Daly was executed for his part in the Easter Rising. Ned was twenty-five years old. His body was consigned to a mass grave.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 297

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The 16LIVES Series

JAMES CONNOLLYLorcan Collins

MICHAEL MALLINBrian Hughes

JOSEPH PLUNKETTHonor O Brolchain

EDWARD DALYHelen Litton

SEÁN HEUSTONJohn Gibney

ROGER CASEMENTAngus Mitchell

SEÁN MACDIARMADABrian Feeney

ÉAMONN CEANNTMary Gallagher

JOHN MACBRIDEWilliam Henry

WILLIE PEARSERoisín Ní Ghairbhí

THOMAS MACDONAGHT Ryle Dwyer

THOMAS CLARKEHelen Litton

THOMAS KENTMeda Ryan

CON COLBERTJohn O’Callaghan

MICHAEL O’HANRAHANConor Kostick

PATRICK PEARSERuán O’Donnell

DEDICATION

To all descendants of the Daly family, Limerick

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I hope this book will help to bring my grand-uncle Commandant Edward Daly out of relative obscurity, to a greater recognition of the part he played in the Easter Rising. I am very grateful to all at O’Brien Press for giving me this opportunity, particularly Michael O’Brien and my editor Susan Houlden; also series editors Lorcan Collins and Ruán O’Donnell: Lorcan was especially helpful.

I particularly wish to thank the following: Dr Anne Cameron, Archives Assistant, Andersonian Library, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow; Maira Canzonieri, Assistant Librarian, Royal College of Music, London; Linda Clayton, Association of Professional Genealogists in Ireland, for tracing Molly Keegan’s life; Maeve Conlan, daughter of Johnny O’Connor, who gave me transcripts of interviews given by her father; Bernie Hannigan, daughter of Patrick Kelly, who gave me a copy of her father’s memoir; Randel Hodkinson, Limerick; Lar Joye, National Museum of Ireland; Mary Monks, Vancouver; Paul O’Brien, for giving me a tour of the Four Courts battlefield; Professor Eunan O’Halpin, Trinity College, Dublin; Dr Terence O’Neill (Colonel, retd) for advice on military strategy; Joseph Scallan, Limerick, for tracking down archives; Deirdre Shortall, Dublin, for translating Irish texts.

I wish to thank the staff of the following institutions for their assistance: The Bureau of Military History, Cathal Brugha Barracks, Dublin; East Sussex Record Office, Lewes, East Sussex; The Frank McCourt Museum, Limerick; Ken Bergin and his staff, Glucksman Library, University of Limerick; Limerick City Archives; Limerick City Museum; Limerick County Museum; National Archives, Bishop Street, Dublin; National Archives, Kew, London; The National Library of Ireland; The National Museum of Ireland.

I thank my husband Frank for his unwavering love, support and patience, and all my family and friends for listening to my moans about ‘lack of material’. Above all, my grateful thanks are due to Edward Daly’s closest living relatives: his nephew and niece Edward and Laura Daly O’Sullivan of Limerick, his nieces Nóra and Mairéad de hÓir, also of Limerick, and their sister-in-law Siobháin de hÓir, of Dublin, who all gave generously of time, advice, anecdotes, photographs and documents. I must also thank my cousin Michael O’Nolan for help with documents and photographs, and all my relatives of the O’Nolan and O’Sullivan families. I happily dedicate this book to them, and to all the Daly descendants, however far-flung.

16LIVES Timeline

1845–51. The Great Hunger in Ireland. One million people die and over the next decades millions more emigrate.

1858, March 17. The Irish Republican Brotherhood, or Fenians, are formed with the express intention of overthrowing British rule in Ireland by whatever means necessary.

1867, February and March. Fenian Uprising.

1870, May. Home Rule movement founded by Isaac Butt, who had previously campaigned for amnesty for Fenian prisoners.

1879–81. The Land War. Violent agrarian agitation against English landlords.

1884, November 1. The Gaelic Athletic Association founded – immediately infiltrated by the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

1893, July 31. Gaelic League founded by Douglas Hyde and Eoin MacNeill. The Gaelic Revival, a period of Irish Nationalism, pride in the language, history, culture and sport.

1900, September. Cumann na nGaedheal (Irish Council) founded by Arthur Griffith.

1905–07.Cumann na nGaedheal, the Dungannon Clubs and the National Council are amalgamated to form Sinn Féin (We Ourselves).

1884, November 1. The Gaelic Athletic Association founded – immediately infiltrated by the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

1893, July 31. Gaelic League founded by Douglas Hyde and Eoin MacNeill. The Gaelic Revival, a period of Irish Nationalism, pride in the language, history, culture and sport.

1900, September.Cumann na nGaedheal (Irish Council) founded by Arthur Griffith.

1905–07.Cumann na nGaedheal, the Dungannon Clubs and the National Council are amalgamated to form Sinn Féin (We Ourselves).

1909, August. Countess Markievicz and Bulmer Hobson organise nationalist youths into Na Fianna Éireann (Warriors of Ireland) a kind of boy scout brigade.1909, August. Countess Markievicz and Bulmer Hobson organise nationalist youths into Na Fianna Éireann (Warriors of Ireland) a kind of boy scout brigade.

1912, April. Asquith introduces the Third Home Rule Bill to the British Parliament. Passed by the Commons and rejected by the Lords, the Bill would have to become law due to the Parliament Act. Home Rule expected to be introduced for Ireland by autumn 1914.

1913, January. Sir Edward Carson and James Craig set up Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) with the intention of defending Ulster against Home Rule.

1913. Jim Larkin, founder of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU) calls for a workers’ strike for better pay and conditions.

1913, August 31. Jim Larkin speaks at a banned rally on Sackville (O’Connell) Street; Bloody Sunday.

1913, November 23. James Connolly, Jack White and Jim Larkin establish the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) in order to protect strikers.

1913, November 25. The Irish Volunteers founded in Dublin to ‘secure the rights and liberties common to all the people of Ireland’.

1914, March 20. Resignations of British officers force British government not to use British army to enforce Home Rule, an event known as the ‘Curragh Mutiny’.

1914, April 2. In Dublin, Agnes O’Farrelly, Mary MacSwiney, Countess Markievicz and others establish Cumann na mBan as a women’s volunteer force dedicated to establishing Irish freedom and assisting the Irish Volunteers.

1914, April 24. A shipment of 35,000 rifles and five million rounds of ammunition is landed at Larne for the UVF.

1914, July 26. Irish Volunteers unload a shipment of 900 rifles and 45,000 rounds of ammunition shipped from Germany aboard Erskine Childers’ yacht, the Asgard. British troops fire on crowd on Bachelors Walk, Dublin. Three citizens are killed.

1914, August 4. Britain declares war on Germany. Home Rule for Ireland shelved for the duration of the First World War.

1914, September 9. Meeting held at Gaelic League headquarters between IRB and other extreme republicans. Initial decision made to stage an uprising while Britain is at war.

1914, September. 170,000 leave the Volunteers and form the National Volunteers or Redmondites. Only 11,000 remain as the Irish Volunteers under Eóin MacNeill.

1915, May–September. Military Council of the IRB is formed. 1915, August 1. Pearse gives fiery oration at the funeral of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa.

1916, January 19–22. James Connolly joins the IRB Military Council, thus ensuring that the ICA shall be involved in the Rising. Rising date confirmed for Easter.

1916, April 20, 4.15pm.The Aud arrives at Tralee Bay, laden with 20,000 German rifles for the Rising. Captain Karl Spindler waits in vain for a signal from shore.

1916, April 21, 2.15am. Roger Casement and his two companions go ashore from U-19 and land on Banna Strand. Casement is arrested at McKenna’s Fort.

6.30pm.The Aud is captured by the British navy and forced to sail towards Cork Harbour.

22 April, 9.30am.The Aud is scuttled by her captain off Daunt’s Rock.

10pm. Eóin MacNeill as chief-of-staff of the Irish Volunteers issues the countermanding order in Dublin to try to stop the Rising.

1916, April 23, 9am, Easter Sunday. The Military Council meets to discuss the situation, considering MacNeill has placed an advertisement in a Sunday newspaper halting all Volunteer operations. The Rising is put on hold for twenty-four hours. Hundreds of copies of The Proclamation of the Republic are printed in Liberty Hall.

1916, April 24, 12 noon, Easter Monday. The Rising begins in Dublin.

16LIVESMAP

16LIVES - Series Introduction

This book is part of a series called 16 LIVES, conceived with the objective of recording for posterity the lives of the sixteen men who were executed after the 1916 Easter Rising. Who were these people and what drove them to commit themselves to violent revolution?

The rank and file as well as the leadership were all from diverse backgrounds. Some were privileged and some had no material wealth. Some were highly educated writers, poets or teachers and others had little formal schooling. Their common desire, to set Ireland on the road to national freedom, united them under the one banner of the army of the Irish Republic. They occupied key buildings in Dublin and around Ireland for one week before they were forced to surrender. The leaders were singled out for harsh treatment and all sixteen men were executed for their role in the Rising.

Meticulously researched yet written in an accessible fashion, the 16 LIVES biographies can be read as individual volumes but together they make a highly collectible series.

Lorcan Collins & Dr Ruán O’Donnell,

16 Lives Series Editors

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Maps

Introduction

Prologue

1 The Dalys of Limerick

2 A Dream Realised

3 Preparations

4 The Clock Strikes

5 Journey’s End

6 Achievement?

Appendix 1 The Daly Sisters

Appendix 2 Edward Daly Letters

Appendix 3

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Plates

About the Author

Copyright

PROLOGUE

On 9 September 1890, the Limerick Reporter and Tipperary Vindicator reported sadly: ‘The death of Mr Edward Daly … which took place rather suddenly at his residence this day, is much regretted by his family and a large circle of friends.’ He was buried on Thursday 11 September, in Mount St Lawrence cemetery, after one of the largest funerals ever seen in Limerick. The cortège was accompanied by several thousand mourners, as bands played funeral airs and men took turns in shouldering the coffin along the shuttered, silent main streets.

The late Edward Daly was undoubtedly a respected man in Limerick’s nationalist circles, having at the age of seventeen spent time in prison for suspected participation in the Fenian movement, a physical-force republican organisation. His daughter Kathleen spoke of his funeral as ‘the biggest spontaneous tribute to a man that I have ever seen’.1 However, it is quite clear from the newspaper accounts that his funeral was deliberately used as the occasion for a massive nationalist protest against the imprisonment of his brother John.

The Munster News stated proudly:

Let no man libel or misrepresent the feelings of those four or five thousand mourners – there was not one amongst them who did not detest and condemn the crime with which John Daly stands charged, but … they met and marched … to show they believed with the dead man in his brother’s innocence.2

The Limerick Reporter averred:

No matter how estimable was Mr Edward Daly in all the relations of life, his funeral procession, which a magnate might envy, was principally indebted in its most imposing features to the fact that it was the funeral of the brother of the persecuted, the high-souled and unpurchasable John Daly, English felon and Irish patriot.3

John Daly was living out his life sentence of penal servitude, for treason and dynamite offences, in Chatham Prison in Kent, which was notorious for its treatment of Fenian prisoners. The Limerick Amnesty Committee, led by his brother Edward, worked tirelessly for his release. Indeed, Edward’s death at the age of forty-one, of heart disease, was partly blamed on the anxiety caused by his brother’s situation, and the exhaustion of the amnesty campaign.

Although Edward Daly might not have been a nationalist icon, as his brother was, his legacy to Irish nationalism was none the less important. Five months after his death, his widow Catharine bore a son, John Edward (Ned) Daly, who was to commit his life to Ireland’s cause at Easter, 1916.

NOTES

1 Kathleen Clarke, Revolutionary Woman (O’Brien Press, 1991), p18.

2Munster News, 13 September 1890.

3Limerick Reporter and Tipperary Vindicator, 16 September 1890.

Chapter One

1840s–1906

The Dalys of Limerick

Commandant Edward Daly was executed on 4 May 1916, aged twenty-five, having been court-martialled for rebellion. Born in Limerick, he was one of the youngest of those executed, and the youngest commandant in the Irish Volunteers. He was also the brother-in-law of Tom Clarke, the dedicated revolutionary who was one of the main movers of the Easter Rising. This biography tells of a lazy schoolboy, a bored office worker, an apparently vain and frivolous young man, who transformed himself into a brave and dedicated leader of the First Battalion of the Irish Volunteers.

His family background, of course, was the start of it. The Limerick family into which Ned Daly was born was reputedly descended from a ‘scribe’, John Daly, from County Galway, who may have been a member of the United Irishmen, the organisation responsible for the 1798 rebellion. The scribe’s son, also John, lived at Harvey’s Quay, Limerick, and worked as a foreman in James Harvey and Sons’ Timber Yard. An excellent singer, this John was a moderate in politics. He supported Daniel O’Connell’s Repeal movement, a non-violent pressure group seeking the repeal of the 1801 Act of Union. This Act had abolished Ireland’s separate parliament, and brought Ireland fully under British control.

Two of the foreman’s sons John (b1845) and Edward (b1848) espoused more radical politics, and in the 1860s they joined the Fenians, a republican group established in 1858 which advocated the use of physical force to win Ireland’s freedom. It was an extremely secretive organisation; when John had sworn the oath, he was astonished to find that his younger brother Edward was already a member, along with every other young man he knew. Although their father believed in peaceful politics, their mother Margaret was more supportive of the Fenian cause, as was their sister Laura (known as Lollie).

In late 1866, the two brothers were arrested after an informer revealed their membership of the Fenians. The magistrate urged Edward not to be influenced by his brother, who was clearly bent on a course of crime. Edward ‘answered him coolly by saying that if he had anything to say his brother would say it for him. How I longed,’ wrote John later, ‘for a chance to throw my arms around him,’ but the handcuffs prevented him. Edward spent two weeks in Limerick Jail. John was later released on bail, in time to take part in the failed Fenian rebellion of 1867, and subsequently made his way to the United States of America. Six years later, Edward married Catharine O’Mara of Ballingarry, County Limerick in January, 1873.1 For a while the couple lived with his parents, and did not start a family until they had a home of their own. Eileen was born in 1876, the first of their eight daughters.2 Edward worked as a lath-splitter, a skilled craft, at Spaight’s Timber Yard in Limerick, during the 1870s. Between 1882 and 1884 he was an attendant at St George’s Asylum, Burgess Hill, Sussex, but left that job on the arrest of his brother John.3 He then seems to have worked as a clerk, possibly back in Spaight’s. At the time of his death in 1890 he was a weighmaster for the Limerick Harbour Board, but had been in poor health for some time, suffering from a heart condition. When the LHB discussed his death at their next meeting, his job was referred to as a ‘sinecure’ (ie a position with little responsibility), and he was not replaced.4

Upon his death an article appeared in the Munster News, on 10 September 1890, emphasising the help he had been given:

For some time it was thought that he would last a few years yet, owing to the extreme kindness with which he was treated during a stay in St John’s Hospital, and the Harbour Board … by giving him lengthened leave, showed their appreciation of his faithfulness to duty, but all was of no avail.

The newspaper urged sympathisers to provide for his family:

By his early death he has left a large and helpless family almost totally unprovided for …. It is well known that the services of the Dalys have ever been given freely in the cause of fatherland.

It was indeed a large family, consisting of the widowed Catharine, her mother-in-law and sister-in-law, and her eight daughters: Eileen, Margaret (Madge), Kathleen, Agnes, Laura, Caroline (Carrie), Annie and Nora. The eldest of the girls was fourteen, and their mother was pregnant again.

A public meeting was held in the Town Hall on 17 September, and a sub-committee was established by nationalist councillors to collect subscriptions for the ‘Edward Daly Family Sustentation Fund’.5 It started with £5; by January it had reached around £130 (about £8,000 today). The amounts collected were published each week, and the collection continued until the following August. The final total reached is unclear, and subscriptions began falling away.

Edward’s brother John, serving his penitential sentence in England, was not told at the time by the family about his brother’s death, but he had known Edward was ill. Writing to his niece Eileen, in a letter published in the Munster News (11 March 1891), he said:

Tell him, that I felt somewhat put out at his not writing to me, but when I heard that he was or had been very sick, oh! Then my heart went out to him, and I could think of him only as the brother who had suffered with me, fought a good fight side by side with me and who would, I am sure, freely share my present sufferings if it were necessary.

John Edward Daly, always known as Ned or Eddie, was born on 25 February 1891 at 22 Frederick Street (now O’Curry Street), Limerick. The sudden death of their father six months earlier had ended the childhood of the three eldest girls, Eileen, Madge and Kathleen, as they took on heavy responsibilities. His mother was trying hard to cope with her new circumstances. Even though her last child was the longed-for son, she found it difficult to focus on him, as though it was all too much to bear. Her daughter Kathleen later wrote:

She seemed resentful that there was no father to whom she could present this little son. Then, gradually, she became absorbed in him. He was very frail, and perhaps this drew her to him more than a robust child would have done …

Two of his sisters walked five miles each day to a farm for milk which was guaranteed free of disease, and this level of anxious care would hover over his whole childhood.6

The Edward Daly Fund ultimately enabled the family to buy a public house in Shannon Street, and Mrs Daly put a hopeful advertisement in the Munster News (19 December 1891):

Mrs Edward Daly begs to announce to her numerous friends and the general public that she has just re-opened the Old Established Bar, No. 3 Shannon Street, where she hopes to be favoured with their patronage and support.

However, the family had no experience in running such a business, and it failed after a year or so. Nationalist sympathisers were very supportive in propping up the bar, but less active in paying off the ‘slates’ they had run up.

Mrs Daly and her sister-in-law Lollie had once run a thriving business as trained dressmakers, but the notoriety of John Daly’s arrest for Fenian activities had driven many respectable clients away. For the next couple of years, the two ladies presumably worked as they could in this profession. The older girls may have worked as shop assistants or sold craftwork, at which Carrie in particular was skilled. Madge, the second eldest, regarded as the brightest of the family, stayed on longer at school, as a pupil-teacher. The girls all attended the Presentation Convent in Sexton Street; their mother washed their pinafores every night, so they could present a good appearance.

At this low point in the family fortunes, a saviour arrived from overseas. James and Michael Daly, older brothers of Edward and John, had emigrated to Australia, one in the 1850s and the other in 1862. They had settled in the French island colony of New Caledonia, and prospered there as traders and sheep-farmers. Now James, whose own children had reached adulthood, decided to take care of his late brother’s family. (Michael, who married three times and is said to have run through three fortunes, never returned to Ireland.)7

Arriving in Limerick in 1894, James moved the whole family to ‘Clonlong’, a large two-storey house with extensive grounds on the Tipperary road. Two of his nieces became shop assistants in Cannock’s department store, and he apprenticed Kathleen to a dressmaker. She was interested in a musical career, but he refused to provide lessons for her because, he said, the money he had spent on his own daughter’s musical training had been thrown away.8

A photograph taken after James’s arrival, in 1894, shows the large family circle in which Ned Daly spent his childhood. His mother Catharine stands to the left, next to James and his sister Lollie, with their mother Margaret (née Hayes) sitting in the middle. The daughters range in age from Eileen, aged twenty, to Nora, aged six. Ned, aged three, can be seen in front in a sailor suit, holding a toy rifle.

The heavily-bearded young man to the right is Jim Jones, who had been informally adopted by the Dalys at three months old when his father Michael died. The family was grateful to Michael Jones, a naval engineer, for helping to smuggle John Daly to the USA in 1867. Jim’s mother (née Lahiff) emigrated to the USA when she was widowed, but never sent for her son as she had promised.

Young Jim, a tireless secretary of the Limerick Amnesty campaign for Fenian prisoners, and a ‘big brother’ to the Daly children, sadly died soon after this photograph was taken, in July 1894, aged twenty-six. He may have died of cholera, which spreads through infected water supplies and kills very rapidly.9 His death must have been a huge shock to them all, particularly Lollie Daly, who had treated him as her own child. Three-year-old Ned had lost the only man of the family, scarcely replaced by an elderly and unfamiliar ‘Uncle James’. Jim Jones was buried in the Daly grave in Mount St Lawrence cemetery, Limerick.

ERIN’S WELCOME TO JOHN DALY

Come close to my bosom my patriot peerless

My brightest, my sturdiest, bravest and best,

So loving and faithful, so fervent and fearless,

My high-hearted hero, come close to my breast …

Come, JOHN, come as swift as the flash of a cannon

To your dear native city, the banks and the bowers

Of your dearly loved river, the far-flashing Shannon,

Where in childhood you wandered amid the wild flowers.

He comes, see he comes! Let your banners flaunt gaily,

He comes! Let the whole nation thrill with his praise.

Let melody welcome untameable DALY,

Let rockets ascend, and let tarbarrels blaze.10

In 1896, when Ned was five years old, this crowded household was enlarged by one. His uncle John, aged fifty-one, Convict No. K562, was released from Portland Prison, where he had been moved from Chatham in 1891.

Having escaped to the USA in 1867, John had joined Clan na Gael, the American Fenian movement, and continued to work for Irish independence. He was sent back to Ireland in 1876 to work with the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), as the Irish Fenians were now known. He became an IRB Central Organiser, and worked for some time as an attendant at St George’s Asylum, Burgess Hill, as his brother was also to do.11 Clan na Gael began to plan a dynamiting campaign in Britain, and indeed later succeeded in 1885 in bombing Westminster and the Tower of London.12 John Daly, returning from the USA apparently as part of this campaign, arrived in Birmingham in April 1884, and was immediately arrested for dynamite offences and sentenced to life imprisonment for treason.

It was believed by his supporters that he had been framed; a statement by the Birmingham chief constable seems to have admitted this, saying that explosives had been obtained in America by an Irish police confederate, and delivered to Daly.13 However, a well-known ‘spycatcher-general’ was adamant that Daly had ordered the bombs himself, and intended to throw one of them from the Gallery of the House of Commons, sacrificing his own life if necessary.14 John himself protested at his trial at Warwick Assizes, in July 1884, that he abhorred physical violence, but he admitted having buried a canister of nitroglycerine in the garden where he was staying.

A man of strong physique and imposing presence, and a gifted orator, John defended himself at his trial, and declared himself willing to endure any sacrifice for his country:

Why, what was love? Was it not a divine inspiration – an inspiration given to man by God? A man without the feeling of love was not fit to live, was not a proper member of the community, and he thanked his God that he at least had love … If he was sent to a dungeon because of that love for his country, would it cure the offence? No, his love would still remain.15

The Limerick branch of the Amnesty Association had worked tirelessly for his release. The Daly home in Clonlong was the centre of this activity, under Jim Jones, who was secretary; the girls sent out appeals and correspondence and arranged public meetings. Kathleen recalled:

I watched everything he [Jim] did, and felt very proud when he allowed me to put the stamps on the letters he was sending out. Later he allowed me to fold the circulars for the post – I am sure I plagued him with my pleading to be allowed to help. In my imagination I was helping to free Uncle John and, of course, Ireland.16

As a result of a long and high-profile campaign, John was elected MP for Limerick in 1893, while still a prisoner. He was disqualified as a felon, of course, but in any case would have boycotted the parliament.

The child Ned would have been too young to participate in all this, but he must have been affected by the frenetic comings and goings, and the tension whenever a letter arrived from the English prisons where Daly was held. Twice, in 1886 and 1888, Edward and Lollie had been called urgently to England because their brother was seriously ill, and expected to die. The crisis in 1886 caused Edward to miss the birth of his daughter Annie; in 1888 John was poisoned by belladonna, having apparently been given the wrong medicine in error. Fortunately, he recovered each time, and his brother and sister would return exhausted by the stressful boat and train journeys.

Conditions for Fenian prisoners were notoriously harsh, and included solitary confinement, poor diet, broken sleep and back-breaking work. Visits were few and strictly controlled, and correspondence was heavily censored. Prisoners were forbidden to touch or speak to one another, and the environment was one of severe sensory deprivation. Many of the prisoners went mad under this treatment. John Daly kept up what correspondence he could with his family, and his flowery oratorical style expressed itself in exhortations to his brother Edward:

Take them [the children] into the country all you can, let them be amongst the fields and the wild flowers. Let them see the land and all the beauties of it. Have them on the Shannon, glorious Shannon, home of my heart’s love I will never see more …

Pour into their young minds all you know of our Country’s history! teach them how to love everything that is beautiful in Nature – how to love truth and honour, and how to hate everything that is wrong, that is mean, that is tyrannical and oppressive …

You must not take from this that I wish your daughters to become politicians, or to take to stumping the Country and ornamenting the gaols. Oh no, God forbid that, but I would have them fit to be Mothers, Spartan Mothers or Limerick Mothers such as our City could once boast of.17

John Daly was finally released because he went on hunger-strike, and his health was severely threatened. He was given amnesty on 15 July 1896 as a ‘ticket-of-leave’ man, which meant that he was released ‘under licence’, with strict conditions of behaviour and travel. His brother James, meeting him at the prison gate, took him to Paris, where some of James’s family were living, to regain his strength; they stayed at the Hotel de Florence.18 The first thing that struck Daly on his release was the sound of women’s voices – he had hardly heard a woman speak in twelve years, apart from the rare visits of his sister Lollie. Catching sight of himself in the railway station mirror, he was shocked at how old he looked. He was described as having a nervous and excitable manner, and appearing prematurely aged, unable to step out with confidence.19

Arriving in Dublin in September, he was greeted by a monster torchlight procession. In Limerick, his carriage was pulled by dozens of men through the streets, and the celebrations went on all night. The excitement when he went through the door to greet his mother was intense. John was now home to stay, a massively popular and heroic figure. He had no intention of abiding by his ‘ticket-of-leave’ conditions, and immediately began a series of propaganda lectures for the Amnesty Association all over Ireland, including Ulster, and in the larger British cities.

After four years as the family mainstay, James Daly decided that it was time for him to move on. It was apparently axiomatic in the family that two Daly men could not live for long in the same house, and the brothers had been quarrelling. James was a constitutional nationalist, and supported the Irish Parliamentary Party. The Fenian physical force tradition was anathema to him, and this created difficulties with his nieces’ political views, as well as those of his brother. He left Limerick in March 1898, and died in December 1900 in New Mayo, Australia.

When James decided to leave, his money went too. John realised that he was now responsible for the support of his mother, his sister, his sister-in-law, and the younger members of the family, but he had no means of employment. In this extremity, and building on the great success of his lectures so far, he contacted his old comrade John Devoy, of Clan na Gael. A fundraising tour of the USA was organised, beginning in New York in November 1897.

This was a huge financial and propaganda success, visiting cities with large Irish populations such as Boston, Detroit, Philadelphia and Baltimore. John, a gifted and passionate speaker, won Irish-American hearts with his emotional accounts of prison life, and his pleas for the remaining prisoners to be set free. The charismatic young beauty Maud Gonne, who had captivated Limerick with her campaigning when John was put up for parliament, accompanied him. They were greeted everywhere with massive demonstrations and patriotic banquets.20

In May 1898, John Daly arrived back in Limerick, financially secure at last. He had enough capital to start a business, and decided to open a bakery. An old friend, a foreman baker, taught him the business, and he set up a shop at 26 William Street, with a bakery behind, and storage space for the four or five horse-drawn delivery vans. Apparently the vanmen would look after the horses themselves at night; one of them, asked where he kept his horse, said, ‘Behind the piano.’

Several of his nieces worked in the shop, which also sold eggs, sweets and cakes, and they were paid a half-crown weekly (two shillings and six pence). Carrie specialised in confectionery. Kathleen, however, had a flourishing dress-making business by this time, and refused to work for her uncle.21 Agnes opened the shop every morning, walking in from Clonlong with eggs from their mother’s chickens. The family soon moved in from Clonlong, however, to the house in William Street.

The name Seágan Ua Dálaig (John Daly in Irish), painted over the shop doors and on the delivery vans, was a deliberate nationalist statement. On opening day, John hired a traditional singer to chant his praises outside the shop, and gave out a free loaf to every customer. The business prospered, and by 1912 John was able to expand into Sarsfield Street, taking over Carmody’s Bakery there and turning it into a confectioner’s shop.

Limerick at the end of the nineteenth century was a thriving port, exporting beef, oats and wheat to the USA and Britain and importing timber, coal and iron. It had a population of about 35,000, with a prosperous Protestant upper class and a growing Catholic middle class. It also had a very vigorous trade union movement. John Daly became a rallying point for Limerick nationalist politics, and fought hard to win a seat on the City Council, but efforts were made to disqualify him from standing, as he was a convicted felon.

He was blackballed when he attempted to join the Shannon Rowing Club. Immediately, Limerick’s nationalist working population opened a subscription list towards a rowing-boat for him. This was presented with much ceremony on the banks of the Shannon, following a torchlight procession accompanied by marching bands. At the head of the procession was a wagon carrying the boat, from which floated the Irish and American flags; the wagon was drawn by four horses with an outrider in green livery. The boat was christenedLua-Tagna (‘Swift to Avenge’).22

Daly raised his profile even further through involvement in the 1898 centenary commemoration of the United Irishmen. In early summer he welcomed Maud Gonne to Castlebar, County Mayo, where a famous battle had taken place in 1798, and presented her with an old French coin and a bullet from the period.23 He also spoke at pro-Boer meetings, which condemned Britain’s actions in the Boer War (1899−1902).

His political career was fortunate in its timing. A massive extension to the franchise in 1884 meant that most male heads of households now had a vote, and artisans and labourers provided the bulk of his support. He headed the local election poll in 1899, and was swept into office as Limerick’s first nationalist mayor. His first act was to order the removal of the Royal Arms from the front of Limerick City Hall. His link on the mayoral chain depicts two crossed pikes and a pair of handcuffs.

John Daly was mayor for three years, retiring in 1902, and was made a Freeman of Limerick in 1904. He turned the first sod for Limerick’s electrical supply in 1902, and is supposed to have been the first to suggest using the Shannon for electrical power – the idea was rejected as impractical. Interested in new technology, he was vilified by Limerick’s horse cabbies and carters when he voted for the introduction of electric trams.24 He presented the Freedom of Limerick to noted nationalists James F Egan (who had been tried and convicted with him in 1884) and Maud Gonne on 10 May 1900.25

This must all have been a most stimulating environment for any child – huge political meetings, torchlight processions, living in the home of Ireland’s most prominent ex-political prisoner, a hub of passionate political activity. But in his early years, Ned did not seem to promise well. A family anecdote has this spoilt lad throwing stones at the unfortunate maid who was bringing him to school, because he was embarrassed at having to walk with a countrywoman wearing an old-fashioned shawl. This must have been while he was attending the Presentation Convent in Sexton Street, until he was seven. He moved to the Christian Brothers in Sexton Street in 1899.

His school records list him as ‘John Edward Daly’, his baptismal name; his residence is given as William Street, and his parent (or guardian) as ‘shopkeeper’.26 He made his First Holy Communion in St Michael’s Church on 26 May 1901. He left school in 1906, aged fifteen, having shown