9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The O'Brien Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

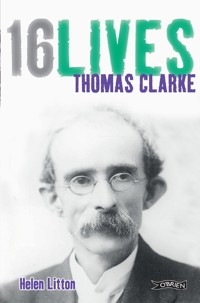

A fascinating examination of the life of Thomas Clarke, a member of the Fenians and a key leader of the Irish Republican Brotherhood in 1916. Clarke spent fifteen years in penal labour for his role in a bombing campaign in London between 1883 and 1898. He was a member of the Supreme Council of the IRB from 1915 and was one of the rebels who planned the 1916 Rising. He was the first signatory of the Proclamation of Independence and was with the group that occupied the GPO. He was executed on 3 May 1916. This accessible biography outlines Clarke's life, from joining the Republican Brotherhood as an eighteen year old, to his execution at the age of fifty-nine.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

The16LIVESSeries

JAMES CONNOLLY Lorcan Collins

MICHAEL MALLIN Brian Hughes

JOSEPH PLUNKETT Honor O Brolchain

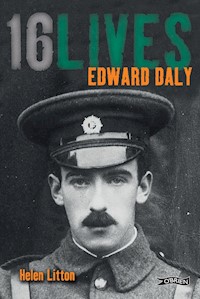

EDWARD DALY Helen Litton

SEÁN HEUSTON John Gibney

ROGER CASEMENT Angus Mitchell

SEÁN MACDIARMADA Brian Feeney

THOMAS CLARKE Helen Litton

ÉAMONN CEANNT Mary Gallagher

WILLIE PEARSE Roisín Ní Ghairbhí

THOMAS MACDONAGH Shane Kenna

JOHN MACBRIDE Donal Fallon

THOMAS KENT Meda Ryan

CON COLBERT John O’Callaghan

MICHAEL O’HANRAHAN Conor Kostick

PATRICK PEARSE Ruán O’Donnell

HELEN LITTON – AUTHOR OF 16LIVES: THOMAS CLARKE

Helen Litton, freelance indexer and editor, has written a series of illustrated histories and edited Kathleen Clarke: Revolutionary Woman, an autobiography (1991). Helen’s paternal grandmother was Laura Daly O’Sullivan of Limerick, sister of Kathleen Daly, the wife of Thomas Clarke and of Commandant Edward Daly, whose biography Helen has written in the 16 Lives series.

LORCAN COLLINS – SERIES EDITOR

Lorcan Collins was born and raised in Dublin. A lifelong interest in Irish history led to the foundation of his hugely-popular 1916 Walking Tour in 1996. He co-authored The Easter Rising: A Guide to Dublin in 1916 (O’Brien Press, 2000) with Conor Kostick. His biography of James Connolly was published in the 16 Lives series in 2012. He is also a regular contributor to radio, television and historical journals. 16 Lives is Lorcan’s concept and he is co-editor of the series.

DR RUÁN O’DONNELL – SERIES EDITOR

Dr Ruán O’Donnell is a senior lecturer at the University of Limerick. A graduate of University College Dublin and the Australian National University, O’Donnell has published extensively on Irish Republicanism. Titles include Robert Emmet and the Rising of 1803, The Impact of 1916 (editor), Special Category, The IRA in English prisons 1968–1978 and The O’Brien Pocket History of the Irish Famine. He is a director of the Irish Manuscripts Commission and a frequent contributor to the national and international media on the subject of Irish revolutionary history.

DEDICATION

For Frank

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful to The O’Brien Press for giving me the opportunity to write this contribution to the study of Tom Clarke, a relatively neglected leader of the Easter Rising. I particularly thank my editor, Mary Webb, for her patience, and the series editors, Lorcan Collins and Ruán O’Donnell.

Thanks are due to the following: Bill Hurley, archivist of the American Irish Historical Association, New York; The Bureau of Military History, Dublin; Siobháin de hÓir, of Dublin, who lent me her father-in-law Éamonn’s unpublished memoirs; the staff of the Brooklyn Public Library, New York; the staff of the John J Burns Library, Boston College; the staff of the Archives Department, University College Dublin; the staff of the National Library of Ireland. Thanks are also due to Linda Clayton, Association of Professional Genealogists in Ireland, for research into the Clarke family.

I am grateful to my husband Frank, Anthony and Kristen, Eleanor and Jim and our grandchildren Aoife and Aidan for all their help and support, and to all family and friends for listening to my moans about ‘too much material and not enough time’. Above all, I am deeply grateful to my uncle and aunt Edward and Laura Daly O’Sullivan, and my cousins Nóra and Mairéad de hÓir, all of Limerick, whose parents fought during the Easter Rising and who shared memories and anecdotes with me.

Finally, I pay tribute to my colleagues of ‘Concerned Relatives of Signatories to the Proclamation’ – Eamonn Ceannt, James Connolly Heron, Muriel McAuley, Pat MacDermott, Honor Ó Brolcháin, Lucille Redmond and Noel Scarlett. Along with other groups, we have been working to preserve the footprint of the retreat and surrender of the Easter Rising, all under threat of demolition. We are grateful that the National Monument of Nos 14-17 Moore Street has recently been reprieved by James Deenihan, Minister for Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, and we hope to see this whole ‘battlefield’ secured and preserved for the centenary of the Easter Rising in 2016.

16LIVES Timeline

1845–51. The Great Hunger in Ireland. One million people die and over the next decades millions more emigrate.

1858, March 17. The Irish Republican Brotherhood, or Fenians, are formed with the express intention of overthrowing British rule in Ireland by whatever means necessary.

1867, February and March. Fenian Uprising.

1870, May. Home Rule movement founded by Isaac Butt, who had previously campaigned for amnesty for Fenian prisoners.

1879–81. The Land War. Violent agrarian agitation against English landlords.

1884, November 1. The Gaelic Athletic Association founded – immediately infiltrated by the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

1893, July 31. Gaelic League founded by Douglas Hyde and Eoin MacNeill. The Gaelic Revival, a period of Irish Nationalism, pride in the language, history, culture and sport.

1900, September.Cumann na nGaedheal (Irish Council) founded by Arthur Griffith.

1905–07.Cumann na nGaedheal, the Dungannon Clubs and the National Council are amalgamated to form Sinn Féin (We Ourselves).

1909, August. Countess Markievicz and Bulmer Hobson organise nationalist youths into Na Fianna Éireann (Warriors of Ireland) a kind of boy scout brigade.

1912, April. Asquith introduces the Third Home Rule Bill to the British Parliament. Passed by the Commons and rejected by the Lords, the Bill would have to become law due to the Parliament Act. Home Rule expected to be introduced for Ireland by autumn 1914.

1913, January. Sir Edward Carson and James Craig set up Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) with the intention of defending Ulster against Home Rule.

1913. Jim Larkin, founder of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU) calls for a workers’ strike for better pay and conditions.

1913, August 31. Jim Larkin speaks at a banned rally on Sackville (O’Connell) Street; Bloody Sunday.

1913, November 23. James Connolly, Jack White and Jim Larkin establish the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) in order to protect strikers.

1913, November 25. The Irish Volunteers founded in Dublin to ‘secure the rights and liberties common to all the people of Ireland’.

1914, March 20. Resignations of British officers force British government not to use British army to enforce Home Rule, an event known as the ‘Curragh Mutiny’.

1914, April 2. In Dublin, Agnes O’Farrelly, Mary MacSwiney, Countess Markievicz and others establish Cumann na mBan as a women’s volunteer force dedicated to establishing Irish freedom and assisting the Irish Volunteers.

1914, April 24. A shipment of 35,000 rifles and five million rounds of ammunition is landed at Larne for the UVF.

1914, July 26. Irish Volunteers unload a shipment of 900 rifles and 45,000 rounds of ammunition shipped from Germany aboard Erskine Childers’ yacht, the Asgard. British troops fire on crowd on Bachelors Walk, Dublin. Three citizens are killed.

1914, August 4. Britain declares war on Germany. Home Rule for Ireland shelved for the duration of the First World War.

1914, September 9. Meeting held at Gaelic League headquarters between IRB and other extreme republicans. Initial decision made to stage an uprising while Britain is at war.

1914, September. 170,000 leave the Volunteers and form the National Volunteers or Redmondites. Only 11,000 remain as the Irish Volunteers under Eóin MacNeill.

1915, May–September. Military Council of the IRB is formed.

1915, August 1. Pearse gives fiery oration at the funeral of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa.

1916, January 19–22. James Connolly joins the IRB Military Council, thus ensuring that the ICA shall be involved in the Rising. Rising date confirmed for Easter.

1916, April 20, 4.15pm.The Aud arrives at Tralee Bay, laden with 20,000 German rifles for the Rising. Captain Karl Spindler waits in vain for a signal from shore.

1916, April 21, 2.15am. Roger Casement and his two companions go ashore from U-19 and land on Banna Strand. Casement is arrested at McKenna’s Fort.

6.30pm.The Aud is captured by the British navy and forced to sail towards Cork Harbour.

22 April, 9.30am.The Aud is scuttled by her captain off Daunt’s Rock.

10pm. Eóin MacNeill as chief-of-staff of the Irish Volunteers issues the countermanding order in Dublin to try to stop the Rising.

1916, April 23, 9am, Easter Sunday. The Military Council meets to discuss the situation, considering MacNeill has placed an advertisement in a Sunday newspaper halting all Volunteer operations. The Rising is put on hold for twenty-four hours. Hundreds of copies of The Proclamation of the Republic are printed in Liberty Hall.

1916, April 24, 12 noon, Easter Monday. The Rising begins in Dublin.

16LIVESMAP

16LIVES- Series Introduction

This book is part of a series called 16 LIVES, conceived with the objective of recording for posterity the lives of the sixteen men who were executed after the 1916 Easter Rising. Who were these people and what drove them to commit themselves to violent revolution?

The rank and file as well as the leadership were all from diverse backgrounds. Some were privileged and some had no material wealth. Some were highly educated writers, poets or teachers and others had little formal schooling. Their common desire, to set Ireland on the road to national freedom, united them under the one banner of the army of the Irish Republic. They occupied key buildings in Dublin and around Ireland for one week before they were forced to surrender. The leaders were singled out for harsh treatment and all sixteen men were executed for their role in the Rising.

Meticulously researched yet written in an accessible fashion, the 16 LIVES biographies can be read as individual volumes but together they make a highly collectible series.

Lorcan Collins & Dr Ruán O’Donnell, 16 Lives Series Editors

CONTENTS

Chapter One

• • • • • •

The Early Years1858-83

‘In a sense, Tom Clarke is a man of one small book, a few letters, and his signature in the 1916 Proclamation.’

This remark by historian Desmond Ryan (who had fought in the GPO) sums up the public image of Tom Clarke.1 A born conspirator, always behind the scenes, Clarke was overshadowed in Easter Rising legend by more charismatic and eloquent figures such as Patrick Pearse, James Connolly and Joseph Plunkett. In recent years new material has become available, and deeper research has begun to alter received ideas about this unassuming-looking man, and to emphasise his absolutely central role in the history of the Rising and the years leading up to it.

Tom Clarke had a somewhat unusual background for an Irish revolutionary, who was to become one of Ireland’s most celebrated rebel leaders. English-born, he had a father whose career was spent in the British Army, and who wanted his son to follow suit.

Tom’s father James, from Errew townland, Carrigallen, County Leitrim, was born in 1830 to James Clarke (or Clerkin), who shared a small farm with his brother Owen, although in his son’s marriage certificate James senior is described as a ‘labourer’. The family was Protestant. When James the younger left school, he worked as a groom, then enlisted as a cavalry soldier on 4 December 1847 in Ballyshannon, County Donegal. His age was given as 17 years and 11 months; he was just under proper age for the army – eighteen – so his first month of service was not counted towards the final total on his discharge.2 He had decided on an army career during the worst years of the Great Famine, when opportunities of employment were few, and a small farm would not have supported a family; his experience with horses made the cavalry a suitable choice for him.

James’s regiment was sent to join the Crimean War (1853-6), in which the English, French and Turks united to fight Russia. This war is mostly remembered now for the Charge of the Light Brigade, and the development of Florence Nightingale’s theories of nursing care. According to his military record, James saw action at the famous battles of Alma, Balaklava and Inkerman in 1854, and the year-long siege of Sebastopol (September 1854-September 1855). He received a medal for the Crimean War, with ‘clasps’ for the three battles and the siege.

He was later garrisoned in Clonmel, County Tipperary, probably on his return from the Crimean War. Here he met Mary Palmer, from Clogheen, and although she was a Catholic, they were married on 31 May 1857 at Shanrahan Church of Ireland parish church, County Tipperary. The marriage record describes her as ‘of full age’ (meaning over 21); her father was Michael Palmer, a labourer.3 Her mother’s maiden name was Kew, and she had obviously been very well-known in her community. According to some anonymous ‘notes’ for a life of Tom Clarke, Mrs Palmer’s funeral in the 1880s (in either Clonmel or Clogheen) was a big public occasion, and she was the first woman waked in the local Catholic church.4

Soon after the marriage James was transferred to Hurst Castle, Hampshire, England, and here their first child, Thomas James Clarke, was born, on 11 March 1858.5 He was baptised a Catholic; the couple obviously came to some agreement on this, or perhaps James was not too concerned about such matters. Catholics marrying Protestants were obliged to rear their children as Catholics.

James must have left the cavalry, because he was now promoted to Bombardier (the lowest rank of non-commissioned officer) in the Royal Artillery in October 1857. He was promoted further, to Corporal, in 1859, and transferred to the 12th Brigade of the Royal Regiment of Artillery. On 9 April 1859, he was sent to South Africa. According to Louis Le Roux, who wrote the first authorised biography of Tom Clarke, the little family ‘narrowly escaped drowning during the voyage when the ship on which they were travelling became involved in a serious collision’.6 A note among the Clarke Papers in the National Library of Ireland says that it was a collision with a coal boat.7

The family spent almost six years in South Africa, in various garrisons. The English and the Dutch South Africans (Boers) had been at loggerheads over the ownership of the province since the late 18th century, as it was an important stop on the trade-routes from Europe to India. The Clarke family was living in Natal when Tom’s sister, Maria Jane, was born on 23 December 1859, and young Tom began attending school there. Natal, annexed by the British from the Boers in 1845, had been separated from the colony in 1856, and granted its own autonomous institutions. It was later one of the four provinces of the Union of South Africa, established in 1910.

James was promoted to Battery Sergeant at the end of 1859, in the Cape of Good Hope. He then re-engaged himself for a period of nine years, starting on 21 March 1860. He and his family returned to Ireland in March 1865, and James was appointed Sergeant of the Ulster Militia. Its headquarters were in Charlemont Castle, County Tyrone. As the barracks accommodation was inadequate to house a growing family, the family moved into Anne Street in Dungannon, the nearby town.

A son, Michael, was born to James and Mary Clarke, in Clogheen, County Tipperary, Mary’s native place, on 9 May 1865. The birth was registered by Bridget Palmer. His father is described as a soldier, ‘resident in Portsmouth’. Mary, who must have travelled from South Africa while pregnant, had probably gone to stay with her family while James, temporarily based in England, arranged the move to Dungannon. Michael must not have lived very long, as he is not part of the family history, but no official record of his death can be found.

James and Mary’s second daughter, Hannah Palmer Clarke, was born in Dungannon on 24 August 1868, and on 26 December of that year James Clarke, Soldier No. 694, claimed his discharge from army service. The record states, ‘Discharge proposed in consequence of his having claimed it on termination of his second period of limited engagement’. James had served for 21 years and nine days, and his discharge was approved, and carried out at Gosport. On 12 January 1869, he was admitted as an out-pensioner of the Royal Hospital, Chelsea, London, aged 39, on a pension of one shilling and 11 pence per day. This was later increased to two shillings and eight pence per day.

He is described in his discharge papers as of swarthy complexion, with dark eyes and hair, with no marks or scars, and 5 feet 7 and a half inches in height. The papers note that his behaviour has been ‘Very Good’. He had two Good Conduct Badges before his first promotion to Bombardier; he had no entries in the regimental ‘Defaulters’ Book’, and had never been tried by court martial.8

The day after his discharge, 13 January, his records state that he was appointed a Sergeant on the permanent staff of the 6th Brigade, Northern Ireland Division, and the family remained in Dungannon.9 Here Alfred Edward was born, on 24 May 1870, in Anne Street. James is described as ‘Sergeant, Tyrone Artillery’. A further birth took place, that of Joseph George, on 16 November 1874; the family was now living in Northland Row. Sadly, Joseph George died on 22 November, having suffered convulsions. His death was registered by James Clarke.10

Tom Clarke was eight years old when his family came to Dungannon, and thus spent almost all of his formative years in the town. A bright boy, he attended St Patrick’s National School. His first teacher was Francis Daly, followed by Cornelius Collins, who employed Tom as an assistant teacher or ‘monitor’. Le Roux says this continued until the school closed in 1881, but Tom had left for the USA in 1880.11 Tom was restless and energetic, and it seemed unlikely that he would remain a schoolteacher for long. A later witness statement says that he failed to move higher than a monitor when he refused to teach Catechism on Sunday mornings. ‘He had no objection to teaching Catechism, but reckoned that Sunday was not included in a teacher’s working week.’12Tom’s best friend was William or Billy Kelly, who assisted Louis Le Roux with his biography of Tom, and also left his own memoir.13

Dungannon, a linen and brickmaking town with a population of about 4,000 in 1881, provided a microcosm of social conditions in Ulster.14 The industries were owned and run by Protestants, and employment for Catholics was limited. There was a clear demarcation between the prosperous homes of Protestants, and the areas where Catholics lived in dreadful conditions, in mud cabins outside the town or tenements within it, and where tuberculosis was rife. Riots between Catholics and Protestants were frequent, when one side would attack the other’s parades or religious processions.

The town had been a focus of reform activity in February 1782, when the Dungannon Convention took place. This gathering of delegates from Volunteer militia corps was looking for parliamentary reform, and drew up a list of demands for government, the ‘Dungannon Resolutions’. The delegates were mostly Protestant, but the thirteenth resolution welcomed a recent relaxation in the Penal Laws which had given more legal rights to Catholics. This movement ultimately led to the establishment, in April 1782, of an independent parliament for Ireland, known as ‘Grattan’s Parliament’. Dungannon’s contribution to legislative freedom made it a gathering-point for local nationalist activity during the nineteenth century. The Fenians or Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) were reorganising and recruiting after two abortive rebellions in 1865 and 1867, and Dungannon had its own District Circle of the IRB.

Tom Clarke, witnessing the inequality and discrimination around him, came to the conclusion that British rule was destroying Ireland, and must be cast off. He was drawn more and more to republicanism, and rejected his father’s plan that he should join the British Army. James Clarke, according to Le Roux, ‘regarded the British Army with superstitious awe, as an unconquerable force, and as the guardian of an unique civilization’. Another statement says that Tom’s father had told him he would be knocking against a stone wall if he tried to fight Britain. ‘Tom Clarke said he would knock away in the hope that some day the wall would give, and in that he forecast the life of poverty, endurance, hardship and singlemindedness that was to be his.’15

The Dungannon District Circle of the IRB met under cover of the Catholic and Total Abstinence Reading Rooms and Dramatic Club. Tom was an active member of this club, but not yet a member of the IRB, when in 1878, when Tom was twenty-one years old, Dungannon was visited by John Daly. Daly, from Limerick, had taken part in the Fenian rising of 1867, and subsequently escaped to America, returning to Ireland in 1869 as a full-time IRB organiser. The IRB was growing, and would soon be an important force within the Land League, the movement for land reform. It would also have some dealings with the Irish Parliamentary Party and its leader, Charles Stewart Parnell. By the mid-1880s it had almost 40,000 members, and 10,000 firearms.

Daly addressed the local IRB groups on Drumco Hill, outside the town. Tom was greatly impressed by him, and resolved to join the IRB. According to Louis Le Roux, he did so in 1882 when, his teaching career having ended, he travelled to Dublin with Billy Kelly and Louis McMullen, his closest friends. The O’Connell Monument, a massive statue to honour Daniel O’Connell, the nineteenth-century lawyer and politician who had espoused non-violent politics and achieved Catholic Emancipation, was to be unveiled in Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street) with great ceremony. On August 14, the day before the unveiling, says Le Roux, John Daly swore Tom Clarke, Billy Kelly and four others from Dungannon into the IRB.

This story cannot be correct; when the O’Connell Monument was unveiled in 1882, Tom and his friends had already been in America for two years. They probably travelled to Dublin in 1879 or 1880, and were sworn into the IRB at that time. Billy Kelly does describe them as travelling for the O’Connell Monument unveiling, but he gives the date of this trip as 1879, and says they met John Daly and Michael Davitt, an ex-IRB man who devoted himself to the cause of land reform.

They travelled to Dublin as members of the Reading Rooms and Dramatic Club, which had organised the excursion. Tom seems to have been quite active on the drama side of the club: ‘The fame of his performance as “Danny Boy” in Dion Boucicault’s “Colleen Bawn” reached Dublin, and Tom refused an invitation by Hubert O’Grady, then a famous actor-manager, to join his touring company’.16 But Tom’s interests lay elsewhere; he was appointed First District Secretary of the Dungannon IRB Circle soon after joining it. The Dramatic Club probably served as a good cover for his activities; his father would undoubtedly have disapproved of them, and might even have betrayed him. Tom later laughed over his efforts at acting; he never took it very seriously, but much of his later life required him to act the part of a harmless little shopkeeper, and he did it very successfully.17

John Daly, who travelled Ireland advising and encouraging IRB groups under cover of being a commercial traveller, visited Dungannon again, probably in 1879. He advised the Tyrone IRB on drilling, training and arming, so that they could defend themselves and others against the activities of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC).

A defining moment in Tom Clarke’s life took place in a sectarian context, when a Catholic ‘Lady Day’ parade, celebrating the Feast of the Assumption, took place on 15 August 1880. The parade was attacked by a crowd of Protestants, and stones were thrown at the RIC. The Riot Act was read, and the police then opened fire on the crowd with live ammunition. One man died and twenty-seven were injured; the police suffered one casualty.18 Louis Le Roux refers to this as the ‘buckshot riot’, as buckshot was fired into the crowd. He then says that one young man, who bore a resemblance to Clarke, was arrested on suspicion of having fired on the police during the riot. When this man was able to prove an alibi, the police began to focus on Clarke himself, who had to lie low for a while.

However, Billy Kelly’s memoir says that on the night following the ‘buckshot riot’, eleven RIC men were ambushed by members of the IRB, who included Clarke and Kelly. The police were fired on, and escaped into a public house in Anne Street. When reinforcements arrived, the attackers had to retreat. This was not reported in the press.19

One way or another, Clarke and his friends were being noticed, and would be better off elsewhere. The decision was made to emigrate to the United States, and on 29 August 1880 a farewell party was held for several young men who were to leave, among them Billy Kelly. Billy was the only one who knew that Clarke intended to travel with them; Tom had not told his parents. As the young men left for the train to Derry, from where they would sail, Tom went home with his family. That night, he slipped out when all were asleep, and made his own way to Derry.

Le Roux says that the boat on which the friends had been booked needed repairs, and they were stuck in Derry for two weeks, receiving two shillings a day detention money from the shipping company. ‘They had a jolly time, making occasional outings on a horse jaunting car, sometimes to Newtowncunningham, in the neighbouring county of Donegal, sometimes as far as Letterkenny.’20

It is perhaps odd that his parents did not catch up with him during this enforced holiday, but they must have had a fairly good idea where he had gone, and his father probably felt they were better off without this trouble-making son. Clarke was now twenty-three years of age, old enough to look after himself.

Clarke and his friends finally took ship on an old cattle boat, the Scandinavia, belonging to the Allen Line. One story says that there was a mutiny on board the boat during the journey, but they ultimately landed safely at Boston, and travelled on to New York by boat.21 Clarke and Kelly lodged in Chatham Street, at the house of Patrick O’Connor, who was from County Tyrone. They worked in his shoe store to begin with, and slept in a stone cellar.

After about two months in O’Connor’s store, Clarke began work as a night porter at the Mansion House Hotel, Brooklyn, ‘where his heaviest duty was to light fifty fires’. The owner, Mr Avery, was establishing a chain of hotels, and found Irish emigrants to be hard-working and honest. He also gave work to Billy Kelly, and promoted Clarke to foreman. However, Avery then sold out to a Dutchman, who sent Kelly to the Garden City Hotel, twenty miles away.

Both Clarke and Kelly had, of course, an introduction to Clan na Gael from the IRB. Clan na Gael had been founded in New York in 1867 by Jerome J. Collins, and it recognised the Supreme Council of the IRB as the government of the Irish Republic ‘virtually established’. Many IRB men who were forced out of Ireland or England joined the Clan on arrival in the USA.

Clarke and Kelly arrived at Clan na Gael’s Napper Tandy Club, or ‘Camp No. 1’, at 4 Union Street, introduced by Pat O’Connor, their first employer, and sworn in by Seumas Connolly, Senior Guardian. Tom proved himself keen and energetic, and was soon made Recording Secretary by the ‘bosses’, Alexander Sullivan, Timothy O’Riordan and Connolly. In 1924 John Kenny, who was president of the club at the time, remembered Tom Clarke as a ‘bright, earnest, wiry, alert young fellow’.22 According to Kelly, the purpose of the club was to instruct its members in the use of explosives, under the tutelage of Dr Thomas Gallagher. ‘Lessons’ included trips to Staten Island to experiment on rocks with nitroglycerine. When a call went out for ‘single men’ as volunteers for dangerous work for Ireland, Clarke and Kelly both volunteered, and joined Dr Gallagher’s classes.23 However, when he moved to Garden City, Kelly could no longer attend meetings, although he continued to send his subscriptions.24

John Devoy, who had been an organiser for the IRB until the rising of 1865, was also a member of this club. Arrested and imprisoned in 1866, he had been released in 1871 on condition of exile, and joined Clan na Gael in the US, building it up to a strong organisation.

During his time in New York, Clarke would no doubt have been an active participant at Clan na Gael’s annual events, such as their Annual Picnic and Gaelic Games each summer, at which dancing was kept up all night, and the celebration of Robert Emmet’s birthday on 4 March each year.25 The Emmet celebrations usually took the form of a mass meeting, at which vehement sentiments were uttered in relation to Britain. One particular meeting resolved ‘That British rule in Ireland is without moral or legal sanction, and does not bind in conscience upon Irishmen one moment longer than that which finds them prepared to cast it off’.26

In 1867 a technological breakthrough had taken place in the field of explosives. Alfred Nobel, a Swedish chemist, took out a patent for ‘dynamite’, an explosive which, it was noted, would ‘level the playing field for terrorists who wished to strike against the state’.27 A mixture of nitroglycerine and black powder, dynamite was developed as an industrial explosive, for mining and construction. However, the risks of premature explosion made it dangerous to use, and strict regulations and guidelines were established in every country where it was available.

Up to that time Fenians who had caused explosions, such as those in Manchester and Clerkenwell, London, in 1867, had used simple gunpowder. Johann Most, a German anarchist, saluted those Fenians, and spoke of ‘the unquenchable spirit of destruction and annihilation which is the perpetual spring of new life’.28 European and Russian anarchists seem to have been the first terrorists to use dynamite.

The two young emigrants had landed into Clan na Gael at a time of great difficulty, when the organisation was being pulled apart by the rivalry between Sullivan, an Irish-American who had little connection with Ireland, and Devoy. By 1881 Sullivan had become supreme ‘boss’, with Michael Boland and Denis Feeley, in a group known as the ‘Triangle’. They advocated a terrorist policy of dynamiting buildings in Britain, and Dr Gallagher directed training on their behalf. Le Roux remarks disapprovingly that Sullivan was a bad judge of men, allowing himself to be conned by an English spy, Henri Le Caron, who headed the British intelligence network active among the Irish-American community.29

The idea of a dynamiting campaign was strongly supported by Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa and Patrick Ford, editor of the Irish World. O’Donovan Rossa had been arrested after the 1863 Fenian uprising and sentenced to life imprisonment. An Amnesty Association, established in 1868 by IRB member John ‘Amnesty’ Nolan, was contacted by him through smuggled letters, and ran a campaign complaining about the harsh prison conditions suffered by IRB prisoners. O’Donovan Rossa was released in 1871, along with Devoy and others, on the condition of exile, and travelled with them to New York.

As irreconcilable as ever, O’Donovan Rossa began to raise money through Ford’s Irish World for a dynamite campaign in England. He hoped this would cause enraged English citizens to attack Irish people living there, and therefore increase Irish support for separatism. John Devoy made an incendiary speech supporting the idea, but in fact Clan na Gael was opposed to it. They were planning a dynamite campaign of their own, but intended it to be much more organised and controlled than O’Donovan Rossa’s ‘one-man terrorist directorate’.30 Devoy knew that the British population would be alienated from any sympathy for Ireland by such a campaign, and that it would encourage the British authorities to maintain a high alert in relation to Irish-American activities. This proved indeed to be the case.

O’Donovan Rossa broke with Clan na Gael in 1880, and between 1881 and 1883, under his direction, bombs were set off in Glasgow, Liverpool, London and Salford. There was one casualty, a young boy killed in Salford.31 Devoy did not gain full control of Clan na Gael until 1890, by which time Tom Clarke was suffering his own consequences from the dynamite campaign.