9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

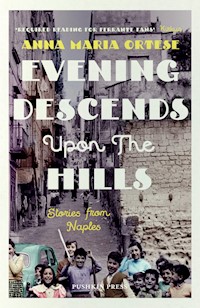

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Classic stories and reportage set in Naples in the 1940s and 50s that inspired Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan Novels A highly evocative classic set in Italy's most vibrant and turbulent metropolis in the immediate aftermath of World War Two. Anna Maria Ortese was one of the most celebrated and original Italian writers of the Twentieth Century. Her stories and reportage, collected in this volume, form a powerful portrait of ordinary lives, both high and low, family dramas, love affairs, and struggles to pay the rent, set against the crumbling courtyards of the city itself, and the dramatic landscape of Naples Bay.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

PUSHKIN PRESS

Evening Descends Upon the Hills

“Anna Maria Ortese is a writer of exceptional prowess and force. The stories collected in this volume, which reverberate with Chekhovian energy and melancholy, are revered in Italy by writers and readers alike. Ann Goldstein and Jenny McPhee reward us with a fresh and scrupulous translation.”

—JHUMPA LAHIRI, author of The Lowland and In Other Words

“As for Naples, today I feel drawn above all by Anna Maria Ortese … If I managed again to write about this city, I would try to craft a text that explores the direction indicated there.”

—ELENA FERRANTE in Frantumaglia: A Writer’s Journey

“This remarkable city portrait, both phantasmagorical and harshly realistic, conveys Naples in all its shabbiness and splendor. Naples appears as both a monster and an immense waiting room, whose inhabitants are caught between resignation and unquenchable resilience. Beautifully translated, this lyrical gem has been rescued from the vast storehouse of superior foreign literature previously ignored.”

—PHILLIP LOPATE, author of Bachelorhood and Waterfront: A Walk Around Manhattan

“This beautiful book is a landmark in Italian literature and a major influence on Elena Ferrante—both as a way of writing about Naples and because Anna Maria Ortese may have been the model for the narrator of Ferrante’s quartet of novels set there. Ann Goldstein and Jenny McPhee have rendered Ortese’s lively, Neapolitan-inflected Italian in vivid, highly engaging English prose.”

—ALEXANDER STILLE, author of The Sack of Rome and Benevolence and Betrayal

EVENING DESCENDS UPON THE HILLS

Stories from Naples

ANNA MARIA ORTESE

Translated by ANN GOLDSTEINand JENNY McPHEE

PUSHKIN PRESS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TRANSLATORS’ INTRODUCTION

In January, 1933, Anna Maria Ortese’s brother Emanuele Carlo, a sailor in the Italian Navy, died during a maneuver off the island of Martinique. “The effect of this news on the household was at first a kind of inferno, but then a strange silence,” Ortese wrote many years later. “It’s like an amputation: a part of the soul is gone forever. And the soul reacts by ceasing to listen to any noise or sound or voice of the surrounding nature or of its own life … That silence, at least for me, who was always alone … lasted several months, and I couldn’t see any way out. Finally, one day—rather, one morning—I suddenly thought that, since I was dying from it, I could at least describe it.” The result was a poem, “Manuele,” published in the review L’Italia Letteraria, in September of the same year. Ortese went on to say, “My life, from that day, changed radically, because now I had a means through which to express myself.” The editor of the review, Corrado Pavolini, continued to publish her poems, among those of such writers as Salvatore Quasimodo, Giuseppe Ungaretti, and Umberto Saba, and suggested that she also try writing stories.

Ortese was born in Rome in 1914, one of six children, into a peripatetic and economically struggling family. Her father was a government employee and was often transferred; the family lived all over Italy and also, for three years, in Libya. In 1928 they settled in Naples, her mother’s native city. Ortese had little formal education, but, with Pavolini’s encouragement, she continued to write stories, publishing them in L’Italia Letteraria and other reviews, many of them under the pseudonym Franca Nicosi, in order to avoid her family’s disapproval. The new editor of L’Italia Letteraria, Massimo Bontempelli, brought her work to the attention of the publisher Valentino Bompiani, and, in 1937, he brought out a collection of her stories, Angelici Dolori (The Sorrows of Angels). When the war came, the family was displaced many times, but in 1945 returned, finally, to Naples. Ortese had begun working as a journalist, while continuing to write stories; in 1950 she published a second collection of stories, and in 1953 Il mare non bagna Napoli, a book that includes both fiction and journalism and published now in English as Evening Descends Upon the Hills.

Evening Descends Upon the Hills presented a Naples “shattered by war,” in which suffering and corruption were widespread and very real. Ortese’s bleak picture takes in not only the struggling masses of the poor but bourgeois, aristocratic, and intellectual Naples as well. Of the five chapters, three are fiction and two are journalistic accounts arising from intensive research and, at times, intrepid reportage. The first story, “A Pair of Eyeglasses,” set mainly among the residents surrounding a squalid courtyard in one of the city’s densely packed neighborhoods, is told essentially from the point of view of a child who is nearly blind, and contrasts the child’s blurred view of her surroundings, and her desire to see clearly, with the brutal, ugly world she will see when she gets her glasses. Vision—seeing, observing, taking in—is both a reality and a stark metaphor for Ortese throughout Evening Descends Upon the Hills. In “Family Interior,” Anastasia, a hardworking shop owner who has been supporting her mother and siblings for years for the first time in her life allows herself to see the grasping, selfish nature of her family, and to imagine something different from her life of “house and shop, shop and house,” but it’s a vision that can’t be sustained: when her mother calls, she can only say “I’m coming.” “The Gold of Forcella” returns to the crowded, destitute Naples of “A Pair of Eyeglasses,” and the desperation of the women who have come to the charity pawnshop of the Bank of Naples to try to get a few thousand lire for some small, precious possession.

“The Involuntary City” is a portrait of the inhabitants of Granili III and IV, a notorious eighteenth-century building intended to be temporary housing for the homeless and the displaced after the war. The essay was first published in the review Il Mondo, in two parts, the second of which was titled “The Horror of Living.” The narrator tries to convey the horror first by a recitation of data about the “structure and population” of the place, but immediately realizes that this is insufficient and goes on to describe entering the “almost absolute” darkness of the groundfloor corridor, making her way through the entire building in order to record the grim human details of life there. Elena Ferrante, long before the publication of The Neapolitan Novels, said of “The Involuntary City” that if she were to write about Naples she would want to explore the direction indicated by Ortese’s account: a story of “small, wretched acts of violence, an abyss of voices and events, tiny terrible gestures.”

The last chapter, the long chronicle “The Silence of Reason,” describes a journey to postwar Naples in which Ortese visits several of the writers and editors who had been her colleagues at the avant-garde literary and cultural magazine Sud, published between 1945 and 1947. In this account, she wanders around Naples, both seeing and recalling people and places, and finds that her former colleagues have, essentially, betrayed their youthful ideals, becoming complacent and bourgeois.

The book brought Ortese attention (“I suddenly found myself almost famous”) and won the Premio Viareggio, an important literary prize, but its reception was mixed. On the one hand, its depiction of a harsh, ugly, impoverished, and corrupt postwar Naples (and postwar Italy) was seen as something new and necessary; on the other the book was viewed as “anti-Naples,” an indictment of the city, particularly by the young intellectuals described in the final chapter as having compromised their beliefs, who saw it as both a personal betrayal and a betrayal of the city. As a result of the book’s “condemnation,” she writes, she “said goodbye to my city—a decision that subsequently became permanent.” Indeed, in the fifty years following the book’s publication, she returned to Naples only once.

Evening Descends Upon the Hills sold well, but Ortese complained that she got nothing from it, having already used up her advance: and this was to be her situation for most of her life. Although she worked constantly, publishing journalism, stories, and eleven novels, she always struggled to have enough money to live, and sometimes had to rely on the financial help of friends. In 1986, the publishing house Adelphi, headed by Roberto Calasso, began reprinting Ortese’s earlier works and publishing her new ones. It was a fortunate development—“They believed in my books [and] published them with respect”—which, finally, brought her acclaim in Italy. She had rarely stayed long in one place, living variously in Milan, Rome, Venice, and Florence, but this, too, changed in her final years, when, with a pension from the government, she was able to settle with her sister in Rapallo. She died there in 1998.

In both her fiction and her reporting, Ortese’s style is an arresting mixture of realist detail and an almost surreal tone, with a strong underlying moral and social sensibility. In a preface to a new edition of Evening Descends Upon the Hills, brought out by Adelphi in 1994, Ortese said of the writing that it “tends toward the high-pitched, encroaches on the hallucinatory, and at almost every point on the page displays, even in its precision, something of the ‘too much.’” This may be particularly true in “The Involuntary City,” in which the smells, sounds, and sights of the place possess these very qualities. Near a mattress on the floor in one room, the narrator says, “there were some crusts of bread, and amid these, barely moving, like dust balls, three long sewer rats were gnawing on the bread.” The voice of the woman who lives in the room “was so normal, in its weary disgust, and the scene so tranquil, and those three animals appeared so sure of being able to gnaw on those crusts of bread, that I had the impression that I was dreaming.”

Similarly in a talk (never delivered) written in 1980 she says: “If I had to define everything that surrounds me: things, in their infinity, or my feeling about things, and this for half a century, I could not use any other word than this: strangeness. And the desire—rather, the painful urgency—to render, in my writing, the feeling of strangeness.” In all the stories of Evening Descends Upon the Hills, people and places that should be familiar are not; in the 1994 preface she talks about her own “disorientation” from reality. This disorientation is literal in “A Pair of Eyeglasses,” when the nearly blind Eugenia finally puts on her eyeglasses: “Her legs were trembling, her head was spinning, and she no longer felt any joy … Suddenly the balconies began to multiply, two thousand, a hundred thousand; the carts piled with vegetables were falling on her; the voices filling the air, the cries, the lashes, struck her head as if she were ill.” And strangeness, or estrangement, is precisely one of the themes of “The Silence of Reason,” in which the narrator arrives at the house of one of her former colleagues and, when no one answers the bell, stands staring through the glass panes of a door into a dark room whose features only gradually, and painstakingly, come into focus, recognizable but different and, ultimately, alienating.

Although no writer can be said to be “easy” to translate, Ortese’s style presents some particular difficulties. Her sentences can be convoluted and complex. The language can sometimes seem repetitive and, as she says, “high-pitched” and “feverish,” qualities that can be off-putting. The metaphors are sometimes bewildering. There are many topographical references to the city of Naples that we didn’t try to explain, but we have provided some basic information about the writers mentioned in the final chapter.

Evening Descends Upon the Hills was first published by Einaudi, in the Gettoni series,* and was originally titled Il mare non bagna Napoli, or Naples Is Not Bathed by the Sea. That title, chosen by Ortese’s editors at Einaudi, Italo Calvino and Elio Vittorini, comes from a line in the story “The Gold of Forcella,” and was intended to signify that although the sea is one of the most beautiful and animating features of Naples, it offers the suffering city no solace or relief. The text of Evening Descends Upon the Hills is based on the 1994 Adelphi edition, and includes the preface and an afterword that was also part of that edition.

For both of us, this was the first experience of co-translating a work of literature. Rather than each being responsible for a number of stories, we divided them, arbitrarily, for a first draft, and then traded. We continued sending the stories back and forth, with discussions in notes, and sometimes in person, until the manuscript was ready.

The role of the translator in a work of literature is much discussed and debated. Some believe that at best the translator is invisible; others say that he or she is, inevitably, a traitor to the original text. Still others claim that the translator is the creator of an entirely new work of literature. As for us, individually, we fall respectively at different places along that continuum.

Whatever the role of the translator, the work of the translator, like the work of the writer, is apparently a solitary endeavor. Yet translating and writing are profoundly collaborative acts across time and texts, involving an ongoing, cacophonous conversation among writers and translators.

We have not only been part of this greater conversation; we have also carried on a conversation with each other for more than twenty years. The decision to challenge and explore our own process as translators by collaborating on a text in this way and seeing what came of it was interesting, informative, surprising, and above all, delightful. Having another person’s ideas and point of view during the practice of translating was both intriguing and invaluable. By the end of our project, we could not have said who had written a given sentence or come up with a particular word. We had in essence merged into yet another translator, who was at once invisible, and at the same time, had a style all her own.

Ann Goldstein and Jenny McPhee

* The Gettoni series, initiated by Elio Vittorini, came out between 1951 and 1958, and included fifty-eight titles, eight by non-Italians. Gettone means “token” in Italian, and up until 2001 a metal token was commonly used in Italy for public telephones, and also for arcade games. The idea was that the books in the series would be affordable and would increase communication and a sense of playfulness through literature by reaching a wide and younger audience. Among the authors published in the Gettoni series were, besides Ortese, Italo Calvino, Lalla Romano, Marguerite Duras, Beppe Fenoglio, Nelson Algren, Leonardo Sciascia, Dylan Thomas, Mario Rigoni Stern, and Jorge Luis Borges.

PREFACE

The “Sea” as Disorientation

Evening Descends Upon the Hills first appeared in Einaudi’s Gettoni series, with an introduction by Elio Vittorini. It was 1953. Italy had come out of the war full of hope, and everything was up for discussion. Owing to its subject matter, my book was also part of the discussion: unfortunately, it was judged to be “anti-Naples.” As a result of this condemnation, I said goodbye to my city—a decision that subsequently became permanent. In the nearly forty years that have passed since then, I have returned to Naples only once, fleetingly, for just a few hours.

At a distance of four decades, and on the occasion of a new edition of the book, I now wonder if Evening really was “anti-Naples,” and what, if anything, I did wrong in the writing of it, and how the book should be read today.

The writing seems to me to be the best place to start, although many may find it difficult to understand how writing can be the unique key to the reading of a text, and provide hints about its possible truth.

Well, the writing in Evening has something of the exalted and the feverish; it tends toward the high-pitched, encroaches on the hallucinatory, and at almost every point on the page displays, even in its precision, something of the too much. Evident in it are all the signs of an authentic neurosis.

That neurosis was mine. It would take too long and would be impossible to say where its origin is; but since it is right to point out an origin, even if confused, I will point out the one that is most incredible and also least suited to the indulgence of the political types (who were, I believe, my only critics and detractors). That origin, and the source of my neurosis, had a single name: metaphysics.

For a very long time, I hated with all my might, almost without knowing it, so-called reality: that mechanism of things that arise in time and are destroyed by time. This reality for me was incomprehensible and ghastly.

Rejection of that reality was the secret of my first book, published in 1937 by Bompiani, and mocked by the champions of the “real” at the time.

I would add that my personal experience of the war (terror everywhere and four years of flight) had brought my irritation with the real to the limit. And the disorientation I suffered from was by now so acute—and was also nearly unmentionable, since it had no validation in the common experience—that it required an extraordinary occasion in order to reveal itself.

That occasion was my encounter with postwar Naples.

Seeing Naples again and grieving for it was not enough. Someone had written that this Naples reflected a universal condition of being torn apart. I agreed, but not to the (implicit) acceptance of this wretched state of affairs. And if the lacerated condition originated in the infinite blindness of life, then it was this life, and its obscure nature, that I invoked.

I myself was shut up in that dark seed of life, and thus—through my neurosis—I was crying out. That is, I cried out.

Naples was shattered by the war, and the suffering and the corruption were very real. But Naples was a limitless city, and it also enjoyed the infinite resources of its natural beauty, the vitality of its roots. I, instead, had no roots, or was about to lose the ones that were left, and I attributed to this beautiful city the disorientation that was primarily mine. The horror that I attributed to the city was my own weakness.

I have long regretted it, and have tried many times to clarify how well I understand the discomfort of a typical Italian reader who wasn’t told—nor did I myself know, nor could I say it—that Evening was only a screen, though not entirely illusory, on which to project the painful disorientation, the “dark suffering of life,” as it came to be called, of the person who had written the book.

The rather sad (or only unusual?) fact remains that the Naples that was offended (was it really offended or only a little indifferent?) and the person accused of having invented a terrible neurosis for the city were never to meet again: almost as if nothing had happened.

And for me, it wasn’t like that.

April 1994

A PAIR OF EYEGLASSES

“As long as there’s the sun … the sun!” the voice of Don Peppino Quaglia crooned softly near the door way of the low, dark, basement apartment. “Leave it to God,” answered the humble and faintly cheerful voice of his wife, Rosa, from inside; she was in bed, moaning in pain from arthritis, complicated by heart disease, and, addressing her sister-in-law, who was in the bathroom, she added: “You know what I’ll do, Nunziata? Later I’ll get up and take the clothes out of the water.”

“Do as you like, to me it seems real madness,” replied the curt, sad voice of Nunziata from that den. “With the pain you have, one more day in bed wouldn’t hurt you!” A silence. “We’ve got to put out some more poison, I found a cockroach in my sleeve this morning.”

From the cot at the back of the room, which was really a cave, with a low vault of dangling spiderwebs, rose the small, calm voice of Eugenia:

“Mamma, today I’m putting on the eyeglasses.”

There was a kind of secret joy in the modest voice of the child, Don Peppino’s third-born. (The first two, Carmela and Luisella, were with the nuns, and would soon take the veil, having been persuaded that this life is a punishment; and the two little ones, Pasqualino and Teresella, were still snoring, as they slept feet to head, in their mother’s bed.)

“Yes, and no doubt you’ll break them right away,” the voice of her aunt, still irritated, insisted, from behind the door of the little room. She made everyone suffer for the disappointments of her life, first among them that she wasn’t married and had to be subject, as she told it, to the charity of her sister-in-law, although she didn’t fail to add that she dedicated this humiliation to God. She had something of her own set aside, however, and wasn’t a bad person, since she had offered to have glasses made for Eugenia when at home they had realized that the child couldn’t see. “With what they cost! A grand total of a good eight thousand lire!” she added. Then they heard the water running in the basin. She was washing her face, squeezing her eyes, which were full of soap, and Eugenia gave up answering.

Besides, she was too, too pleased.

A week earlier, she had gone with her aunt to an optician on Via Roma. There, in that elegant shop, full of polished tables and with a marvelous green reflection pouring in through a blind, the doctor had measured her sight, making her read many times, through certain lenses that he kept changing, entire columns of letters of the alphabet, printed on a card, some as big as boxes, others as tiny as pins. “This poor girl is almost blind,” he had said then, with a kind of pity, to her aunt, “she should no longer be deprived of lenses.” And right away, while Eugenia, sitting on a stool, waited anxiously, he had placed over her eyes another pair of lenses, with a white metal frame, and had said: “Now look into the street.” Eugenia stood up, her legs trembling with emotion, and was unable to suppress a little cry of joy. On the sidewalk, so many well-dressed people were passing, slightly smaller than normal but very distinct: ladies in silk dresses with powdered faces, young men with long hair and bright-colored sweaters, white-bearded old men with pink hands resting on silver-handled canes; and, in the middle of the street, some beautiful automobiles that looked like toys, their bodies painted red or teal, all shiny; green trolleys as big as houses, with their windows lowered, and behind the windows so many people in elegant clothes. Across the street, on the opposite sidewalk, were beautiful shops, with windows like mirrors, full of things so fine they elicited a kind of longing; some shop boys in black aprons were polishing the windows from the street. At a café with red and yellow tables, some golden-haired girls were sitting outside, legs crossed. They laughed and drank from big colored glasses. Above the café, because it was already spring, the balcony windows were open and embroidered curtains swayed, and behind the curtains were fragments of blue and gilded paintings, and heavy, sparkling chandeliers of gold and crystal, like baskets of artificial fruit. A marvel. Transported by all that splendor, she hadn’t followed the conversation between the doctor and her aunt. Her aunt, in the brown dress she wore to Mass, and standing back from the glass counter with a timidity unnatural to her, now broached the question of the cost: “Doctor, please, give us a good price … we’re poor folk …” and when she heard “eight thousand lire” she nearly fainted.

“Two lenses! What are you saying! Jesus Mary!”

“Look, ignorant people …” the doctor answered, replacing the other lenses after polishing them with the glove, “don’t calculate anything. And when you give the child two lenses, you’ll be able to tell me if she sees better. She takes nine diopters on one side, and ten on the other, if you want to know … she’s almost blind.”

While the doctor was writing the child’s first and last name—“Eugenia Quaglia, Vicolo della Cupa at Santa Maria in Portico”—Nunziata had gone over to Eugenia, who, standing in the doorway of the shop and holding up the glasses in her small, sweaty hands, was not at all tired of gazing through them: “Look, look, my dear! See what your consolation costs! Eight thousand lire, did you hear? A grand total of a good eight thousand lire!” She was almost suffocating. Eugenia had turned all red, not so much because of the rebuke as because the young woman at the cash register was looking at her, while her aunt was making that observation, which declared the family’s poverty. She took off the glasses.

“But how is it, so young and already so nearsighted?” the young woman had asked Nunziata, while she signed the receipt for the deposit. “And so shabby, too!” she added.

“Young lady, in our house we all have good eyes, this is a misfortune that came upon us … along with the rest. God rubs salt in the wound.”

“Come back in eight days,” the doctor had said. “I’ll have them for you.”

Leaving, Eugenia had tripped on the step.

“Thank you, Aunt Nunzia,” she had said after a while. “I’m always rude to you. I talk back to you, and you are so kind, buying me eyeglasses.”

Her voice trembled.

“My child, it’s better not to see the world than to see it,” Nunziata had answered with sudden melancholy.

Eugenia hadn’t answered her that time, either. Aunt Nunzia was often so strange, she wept and shouted for no good reason, she said so many bad words, and yet she went to Mass regularly, she was a good Christian, and when it came to helping someone in trouble she always volunteered, wholeheartedly. One didn’t have to watch over her.