8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

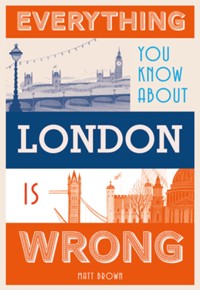

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Everything You Know About...

- Sprache: Englisch

A highly entertaining read for anyone with even a passing interest in art and art history. This myth-busting book takes you on a great ride through the lives of starving (and not so starving) artists, unusual exhibitions and painting blunders throughout history. In the intriguing, outrageous and often provoking world of the visual arts, nothing is quite as it seems. From the world's first intance of photobombing in 1843 to the Damien Hirst spot painting that landed on Mars, the destruction of Vincent van Gogh's Sunflowers during World War II and the £3,500 sheet of paper crumpled into a ball, Everything You Know About Art is Wrong will confound your assumptions about the world of art – and perhaps even the place of art in the world.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 203

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Everything You Know About Art Is Wrong

Everything You Know About Art Is Wrong

Matt Brown

Contents

Introduction

The World of Art

All artists are tortured geniuses who live Bohemian but impoverished lifestyles

Art is a young person’s game

Art is useless, a waste of money

Primitive art is inferior to Western art

A true work of art must be unique

Between the ancient world and the Renaissance, art was effectively dead

Art is all about wandering around galleries

Women couldn’t make a career out of art until the 20th century

True artists should do the work themselves

Painting

The oldest art in the world can be found in the caves of Lascaux in France

Still-life paintings are dull and unimaginative

Caravaggio changed painting forever with his candlelit scenes

The Impressionists were the first to truly paint outdoors

Van Gogh only sliced off part of his ear

Kandinsky invented Abstract art

Painting is dead – nobody does it anymore

Sculpture

Ancient sculptures are plain and boring

The Statue of Liberty is the largest sculpture in the world

Equestrian statues contain a hidden code showing how the subject died

Easter Island contains hundreds of mysterious stone heads

Architecture

There are three classical orders of architecture

The keystone is the most important stone in an arch

Nobody built in concrete before the 20th century

Modern architecture is all just monotonous glass and steel

Stonehenge was built by druids (and other landmark lies)

Other Art Forms

The invention of photography was seen as a major threat to artists

Walt Disney designed Mickey Mouse, who first appeared in Steamboat Willie

The famous tapestry made in Bayeux shows how King Harold took an arrow in the eye at the Battle of Hastings

Most street artists are teenage boys who illegally spray on walls

Conceptual art is a load of rubbish that anyone could put together

Art’s Daftest Conspiracy Theories

The Mona Lisa is actually a hidden self-portrait of Leonardo

Michelangelo hid anatomical sketches in the Sistine Chapel

Van Gogh was colour-blind

Goya’s Black Paintings were forgeries, made after his death

Rembrandt used mirrors and lenses to paint his masterpieces

Walter Sickert was Jack the Ripper

Leonardo’s Last Supper is full of secret codes

Further misquotes and minor misconceptions

Are you pronouncing it wrong?

Let’s start a new wave of false facts

Further information

Index

About the author

Introduction

This is a book about the joys and opportunities of being wrong. Specifically, being wrong about art in any form. One of my earliest memories involves being wrong about art.

As a young child, I watched an art show in which the host created beautiful images with pastels. This was exciting. I wanted to have a go. If I could get my hands on some pastels, I could impress my chums, who were still struggling along with felt tips, wax crayons and the wishy-washy paints of the infant classroom. Pastels looked sophisticated.

Clutching my pocket money, I marched round to the supermarket, bought my supplies and headed into school. But something went wrong. My pack contained a range of coloured pastels, but none of them would leave much of a mark on paper. Worse, my sheet became torn and sugar coated as I dragged the pastels across its surface. Turns out that fruit pastilles are not the same thing as pastel crayons.

It was an embarrassing mistake, but one I never forgot. That’s the thing about getting something wrong – it sticks in the memory. And that is where the inspiration for these books comes from. Presented in these pages are dozens of ideas about art that many of us take for granted which, with some probing, turn out to be wrong, or only partially correct.

Despite the title, my chief ambition here is not to poke holes in people’s knowledge nor to ridicule common ignorance. Rather, I’m hoping to tell the story of art through a different filter. If it’s true that we learn best from our mistakes, then it seems to me that a focus on those mistakes is the most efficient way to get under the skin of a subject.

One of the pitfalls of describing art is that, to use an old cliché, a picture is worth a thousand words. A writer will often spend several paragraphs minutely describing the appearance of a painting – partly because the book’s illustration budget didn’t allow for reproductions. Neither does mine. But nor, in the 21st century, does it need to. Most of us now have a smartphone or tablet within reach at all times – you might even be reading on one. If I mention an unfamiliar work of art in the text, by all means look it up on an image search. Pan around; zoom in. Get a feel for the work before returning to the book. It’s not cheating. Quite the opposite. You can often study paintings at far higher resolution than any print reproduction would allow, and I’d rather fill these pages with intriguing stories than labour away at descriptions.

Another peril before me is the nebulous nature of the topic. The question ‘What is art?’ has an infinity of answers, and my personal take on the subject may well be very different from yours. I’ve chosen to focus on the so-called fine arts of painting and sculpture, with elements of drawing, photography and architecture thrown in for good measure. I'm aware that the topics also have a strong bias towards Western art. This is a necessary and inevitable limitation of a book dealing with misconceptions among a mostly Western audience.

So, sit back, prepare to abandon your old beliefs and prejudices about art, open a packet of fruit pastilles, and let the nitpicking begin.

The World of Art

All artists are tortured geniuses who live Bohemian but impoverished lifestyles

We all have a picture in our heads of the stereotypical artist: a tatterdemalion maestro, frantically working at his canvas. A loner, locked away in his garret for hours, with only a bottle of absinthe, a pile of final demands and the demons in his head for company. The artist must suffer for his art.

Like all stereotypes, this picture contains a kernel of truth. Many artists have worked under impoverished conditions. Some of the biggest names in art suffered from mental-health issues. Plenty of artists have risked their well-being and finances in pursuit of creative perfection.

Is that right, though? Is it always like that? Well, of course not. Artists come in all shapes, flavours and income brackets, just like people of any other profession. Yes, there have been several notable artists with troubled minds – van Gogh (1853–90) and Goya (1746–1828) to name but two – but one might also list dozens of musicians, authors and composers who have struggled with mental-health difficulties. The list need not be limited to traditional creative types, either. Statesmen such as Caligula, Lincoln and Churchill, and the entrepreneur Howard Hughes, are all high-profile examples. Artists have no monopoly on a tortured mind.

What about the notion that mental instability can drive creativity? After all, van Gogh painted some of his greatest works, including Starry Night, while living in a mental asylum. The old platitude that ‘there’s a fine line between madness and genius’ might seem reasonable. After all, creative people are, by definition, those who are able to use their minds in ways that others can’t. Indeed, scientific studies, published in respectable journals, have shown links between creativity and mental illness. In one study, artists and other creative professionals were found to be 25 per cent more likely to carry genes associated with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. To bend a crass cliché, you don’t have to be crazy to work as an artist, but it helps.

Or does it? Correlation does not imply causation. Artists might be more likely to suffer from mental-health problems, but that does not mean their ailments drive their creative powers. One could think of alternative theories for the genetic connection. It could be that those with mental illnesses are drawn towards the arts more than those without, as an outlet for emotions. It’s not that their difficulties make them more creative, but that they’re more likely to pick up a paintbrush in the first place. Other credible research has shown that creativity is enhanced by a positive mood, and inhibited by a negative mood, seemingly contrary to the expectations of the ‘tortured genius’. Whatever the case, the connection between creativity and mental illness remains debatable.

The myth of the starving artist, meanwhile, has many origins, both real and fictional. One oft-quoted source is the 19th-century novel Scènes de la vie de bohème by Henri Murger (1822–61). This popular book depicted a set of indigent artists living in the Bohemian quarter of Paris. This lifestyle – eschewing the pursuit of wealth for the purity of art – became the romantic ideal of the struggling artist. The great creators must cast aside everyday distractions like eating, personal hygiene and earning a wage, and put all their powers into their work.

The passionate struggle may be seen in some artists, but it’s also true of anyone with a driven mind. How many business owners put in 15-hour days to get their start-up off the ground? I’ve known accountants burn the midnight oil in order to complete tax returns. The notion of going without food, rest or sleep to focus on just one thing will sound very familiar to anybody with a small child. Artists are not the only ones to toil.

The idea that artists must spend their lives as paupers is also flawed. History is littered with wealthy artists, as well as poor ones. Michelangelo (1475–1564), despite constantly complaining about his unpaid commissions, amassed a personal fortune estimated at £30 million in today’s money. His contemporaries, such as Leonardo (1452–1519), Raphael (1483–1520) and Titian (1490–1576), were not quite so flush, but all lived in style, with grand houses and fine clothes.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) amassed his great wealth from the English Crown, and lived in a suite of rooms at the royal palace of Eltham near London. His tomb in St Paul’s Cathedral was destroyed during the Great Fire of 1666, but recorded a life lived magnificently, ‘more like a prince than a painter’. Society portrait specialists, such as Joshua Reynolds (1723–92) and John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), were able to live well-to-do lifestyles, socializing with their wealthy patrons. Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) inherited a fortune from his banker father, and never struggled to pay a bill. When Picasso (1881–1973) died, his estate was audited at between $100 million and $250 million. In today’s money, he might have been a billionaire. Many further examples can be plucked from the history books, perhaps enough to cancel out such painter-paupers as Rembrandt (1606–69), Gauguin (1848–1903) and Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901).

The difference between rich and poor is even greater in today’s art world. At the top end, Damien Hirst (born 1965) presides over a fortune estimated at $1 billion, making him the wealthiest artist of all time. This is an artist whose works include a platinum skull encrusted in diamonds. He’s also the only artist to have a work of art on Mars*. All a far cry from the struggling romantic labouring away in a bedsit.

Hirst is not alone. Half a dozen living artists – among them Jeff Koons (born 1955) and Takashi Murakami (born 1962) – command bank accounts with nine figures. On the other hand, the world has no shortage of art students struggling to make ends meet. But is that because they’re artists, or because they’re students?

* FOOTNOTE One of the artist’s spot paintings was carried by the British Beagle 2 probe, launched in 2003, to be used as a colour calibration chart for the robot’s sensors. Unfortunately, contact was lost with Beagle 2 before it could send back any data. We now know that Beagle made it safely to the surface but was unable to contact Earth. Hirst’s spot painting is almost certainly intact, and therefore the only work of art on Mars.

Art is a young person’s game

The windswept Barnoon Cemetery in St Ives ranks among the most photographed in England. Its belichened gravestones have featured in countless films and TV programmes thanks to their outlook over the azure Cornish seas. Among the tumble of weather-beaten headstones lies something unique – a lighthouse. This is not a beacon to warn people away, but a pictorial lighthouse, marked on a grave to draw in the curious. This monument in glazed, coloured stone is the most impressive in the cemetery. Yet it marks the final resting place of a working-class fisherman.

Alfred Wallis (1855–1942) was in many ways a typical Cornish labourer. From a young age, he would venture out to sea on fishing boats and merchant vessels, sailing as far as Newfoundland. In later years, Wallis turned to scrap dealing, and the sale of marine equipment. It was a hard life, but not an unusual one. Then, the loss of his wife in 1922 changed everything. The ageing fisherman took up painting ‘for company’, and filled his house with depictions of the sea.

It was a case of right place, right time. A few years later, the noted artists Ben Nicholson (1894–1982) and Kit Wood (1901–30) arrived in St Ives, hoping to establish an artists’ colony. They were enchanted by the paintings of this humble fisherman, now well into his 70s. Although in many ways naive, Wallis’s seascapes possessed a clarity borne of deep familiarity. As Nicholson put it, the paintings showed ‘something that has grown out of the Cornish seas and earth and which will endure’.

Wallis became a big influence on the artists, and helped cement St Ives’ reputation for art, still intact today. Although he may never have picked up a paintbrush until he was almost 70, Wallis went on to become a celebrated artist whose work is still much loved. Some of his paintings can be viewed in the St Ives branch of the Tate gallery, a few hundred metres from his distinctive grave.

Wallis bucks the notion – common across the arts – that creativity is a young person’s game. Great art needs great energy and passion, and the courage to rebel against the establishment. Life saps this vigour. Our drive and ingenuity diminish as our hair greys. Or so the prejudice goes. We tend to lionize those painters who suffered for their art and died young: think van Gogh (aged 37), Kahlo (aged 47), Caravaggio (aged 38), Modigliani (aged 35), Pollock (aged 44) or Basquiat (aged 27). But a great deal of the best work comes with maturity. There is no shortage of examples of famous artists working well beyond the usual age of retirement or, in cases like Wallis, only beginning an artistic career at this age.

Another notable latecomer is Alma Thomas (1891–1978), an Expressionist painter from Washington D.C. Unlike Wallis, Thomas had always had a fizz of creativity about her; she was the first student to be awarded a Batchelor’s degree in Fine Art from Howard University, and served for many years as an art teacher. But she only set up as a professional painter upon retiring from education in 1960, by which time she was 71. Many of her best works – colourful abstract designs – were made in her 80s. One of her paintings was chosen for the White House during the Obama administration.

Self-taught artist Henri Rousseau (1844–1910) didn’t leave it quite so late. The French customs officer was merely in his 40s when he made his artistic debut. Though naive in style, his paintings now hang in the world’s top art galleries. The Abstract Expressionist Janet Sobel (1894–1968) was another who only took up art in her middle years. Despite the late start, she contributed to the emergence of drip painting, more commonly associated with Jackson Pollock.

Surely the most extreme example is the Aboriginal Australian artist Loongkoonan (born 1910). She first decided to paint at the age of 95 and, at the time of writing, is still going strong at 105 years old. Her works draw on a century of memories, depicting indigenous motifs with colourful painted dots. She has achieved fame in her native country and has recently exhibited in Washington D.C., although the journey was too long to allow her to attend in person.

As well as late-found talent, the history of art is littered with longevity among established artists. Many of the Old Masters created their best work in later life. The Venetian master Titian (c.1490–1576) lived to an indeterminate age between 80 and 100, though most likely around 90. Creative until the very end, his final painting, Pietà, was (almost) completed in the year of his death, and was possibly intended to hang in his tomb. Not everyone thought his staunch refusal to retire was a good idea. The contemporary art historian Giorgio Vasari (1511–74) wrote that ‘It would have been better for him in those last years to have painted only as a hobby so as not to diminish the reputation gained in his best years.’ This final phase in Titian’s life is now much better appreciated. His looser use of the brush, perhaps the effect of increasing frailty, gives his late works a certain freedom, which edges towards Impressionism. Other octogenarian Old Masters include sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini (died 1680, aged 81), portraitist Frans Hals (died 1666, aged 84), and, of course, Michelangelo, who kept chipping away at marble until he finally keeled over in 1564, aged 88.

Indeed, few artists ever do retire, unless forced into it by infirmity. Once the creative urge is unleashed and nurtured, it becomes part of the artist’s identity that cannot be quashed. Many artists not only continue to make art into old age, they continue to make great art. The hugely influential artist Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010), for example, began her career in the 1930s and was busy right up to her death at almost 100. Her most famous pieces, giant spider sculptures that have been exhibited all over the world, were created in the 1990s while Bourgeois was in her 80s. Henri Matisse (1869–1954) saved his most original work for his final decade. Bedridden with illness, he turned to the art of collage, creating his famous cut-outs with the help of assistants.

The most noted example is Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), who lived to the ripe old age of 91, producing art that was fresh and adventurous (some would say pornographic) right to the end. His late works sell for multi-millions at auction. The most expensive of all, Les Femmes d'Alger, was painted in 1955 when Picasso was in his mid-70s. It sold for $179.4 million in 2015, and remains one of the most valuable artworks in the world.

Art is useless, a waste of money

It’s easy to dismiss the art world, and many people do. What is the point of all this useless beauty? How does a portrait of a forgotten Venetian merchant enrich my life? Why should we spend so much public money on subsidizing art, when the funds might instead be diverted to hospital beds, or teacher training, or improving the transport network? What use is art? These are all good questions. We better have some good answers.

First, why do things need to have a use to be worthwhile? A football team has no use. Not really. Those eleven men or women entertain their fans, but they don’t train up nurses or lay new rail tracks or do anything else that might reasonably be described as useful. Soap operas have no use, but it doesn’t stop people tuning in by the million. To quote an old cliché, what use is a newborn baby? Isn’t it enough that art brings pleasure to, and enriches the lives of, those who seek it out?

And, anyway, art does have its uses – plenty of them. We can learn so much from studying paintings and sculpture. The dedicated art-goer will, over time, hone the skills of observation, and acquire different ways of looking at the world. Historical paintings can spark an interest in past events, and give us at least some sense of what it might have been like to witness them. Likewise, paintings on religious or mythological themes reinforce our understanding of those worldviews.

Art through history had many purposes other than to look pretty, and that is still true today. Next time somebody blithely declares that art is ‘useless’, a ‘waste of time’ or a ‘waste of money’, consider drawing from the following list that shows just how useful art can be.

As an aid to learning Art can teach us much about the history and cultures of the world, and it has often been employed for pedagogical purposes. Christian religious paintings and stained-glass windows, for example, were partly intended to remind an illiterate audience about the lessons of the Bible. Similarly, the story of the Buddha has been told and retold through countless sculptures and reliefs. Historical paintings bring to life naval engagements, coronations or calamities from the centuries when photography or video did not exist to record such occasions for posterity. In addition, many of the great names of history would be faceless to us without the arts of portraiture and sculpture. Would Elizabeth I or Napoleon resonate in our imaginations to the same degree if we did not know what they looked like?

For political propaganda History brims over with examples of art and imagery bent to political ends. Army recruitment posters featuring Uncle Sam or Lord Kitchener readily spring to mind. A more recent example is the HOPE image of Barack Obama, created by street artist Shepard Fairey (born 1970); and subsequently the spin-off NOPE posters of anti-Trump protesters. Art as propaganda is as old as civilization. The Assyrians and Babylonians, for example, recorded their victories in mighty friezes – a way of aggrandizing the king or military leader and cementing his reputation among the populace.

For devotion and meditation Today’s action figures – often depicting muscular characters with superhero powers – would be very familiar to the Romans. Every Roman home had its sculpted figurines, known as Lares, which were used as devotional objects. Just like today’s action figures, these small statues came in innumerable forms, and represented powerful individuals – usually gods or ancestral spirits rather than Ninja Turtles or Jedi Knights. The figures were placed in household shrines, often painted with additional Lares. Similar sculptural and painted forms, created for meditative purpose, can be found in many other cultures around the world. Buddhists use complex symbolic and geometric patterns known as mandalas to help with this. The act of creation can itself be meditative. The amateur watercolourist takes his or her easel outdoors as much to find inner peace as to create a work of art.

To amuse There’s a whole world of cartoon, animation and humorous greeting cards out there designed to make us chuckle, but artists have been raising a smirk for millennia. Satirical drawings are known from the ancient world. An Egyptian stone dating back to more than 1,000 years BCE, for example, shows a cat serving food to a seated mouse. It is the original lolcat. Medieval manuscripts often contain ribald depictions of bodily functions, surely drawn with humorous intention. William Hogarth (1697–1764) made his name by painting satirical views of 18th-century society, as did numerous cartoonists in the emerging press. The Surrealists gave a new lease of life to humour in art, from Salvador Dalí’s (1904–89) lobster telephone to René Magritte’s (1898–1967) La Clairvoyance, which shows a man painting a bird, while looking at an egg. The rise of street art and the spread of visual media through the Internet have only increased our appetite for humorous art.

To assist in the afterlife The ancient Egyptians put a lot of effort into death. No self-respecting pharaoh would go to his tomb without a heap of useful objects for use on the other side. The walls of his burial chamber would be painted with similar goods and comestibles, as well as the images of servants.

As memorial