0,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: E-BOOKARAMA

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

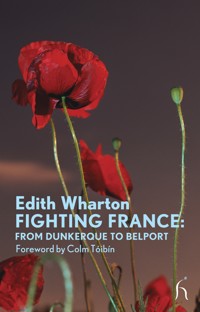

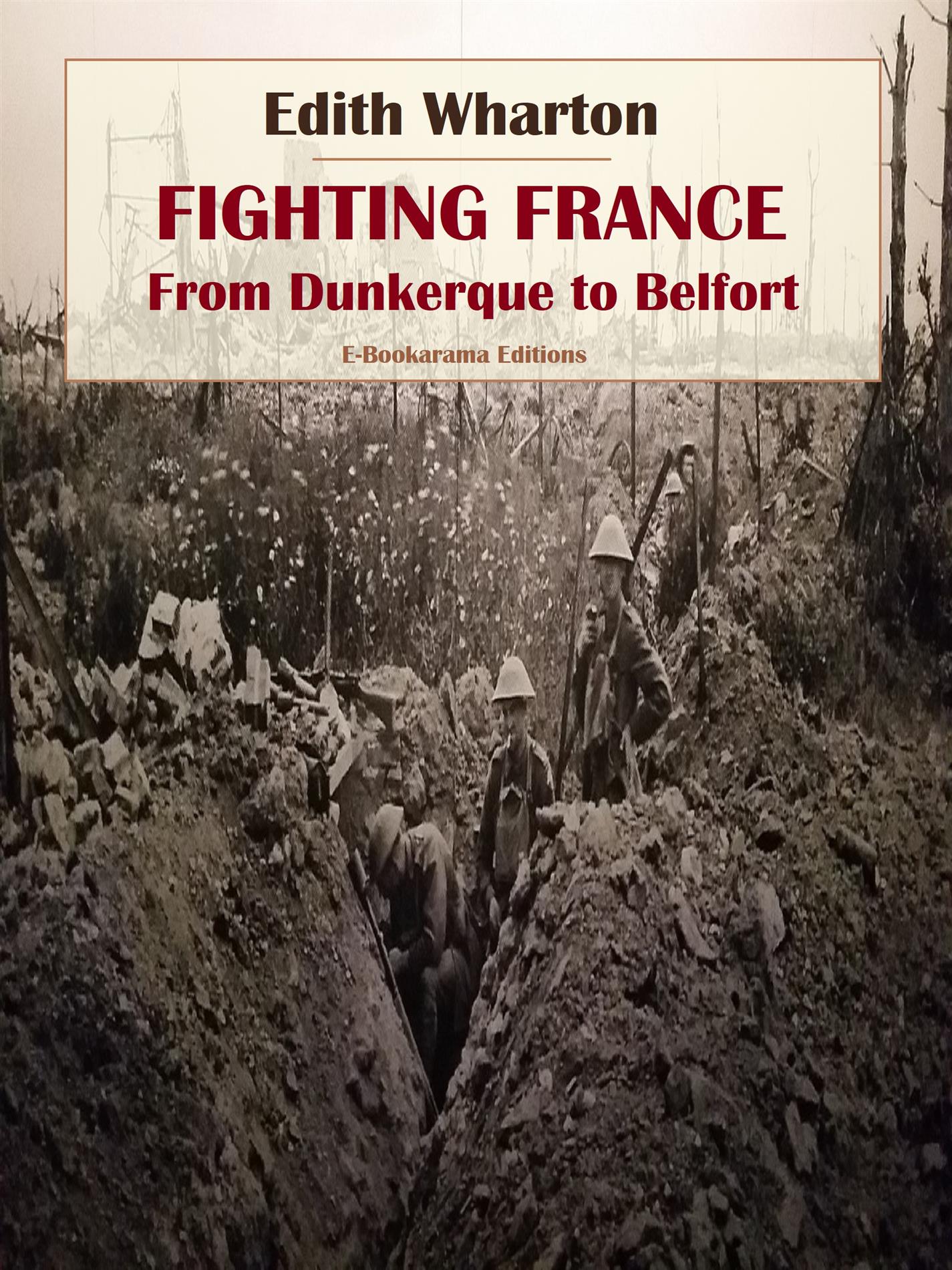

American novelist Edith Wharton was living in Paris when World War I broke out in 1914. She obtained permission to visit sites behind the lines, including hospitals, ravaged villages, and trenches. "Fighting France, from Dunkerque to Belfort" records her travels along the front in 1914 and 1915, and celebrates the indomitable spirit of the French people.

Edith Wharton was one of the first woman writers to be allowed to visit the war zones in France. This resulting collection of 6 essays presents a fascinating and unique perspective on wartime France by one of America’s great novelists. Written with Wharton’s distinctive literary skills to advocate American intervention in the war, this little-known war text demonstrates that she was a complex and accomplished propagandist.

However, these eyewitness accounts also demonstrate a troubling awareness of the human cost of war.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Table of contents

FIGHTING FRANCE, FROM DUNKERQUE TO BELFORT

The Look of Paris

I: August

II

III: February

In Argonne

I

II

In Lorraine and the Vosges

In the North

In Alsace

The Tone of France

FIGHTING FRANCE, FROM DUNKERQUE TO BELFORT

The Look of Paris

(August, 1914-Febuary, 1915)

I: August

On the 30th of July, 1914, motoring north from Poitiers, we had lunched somewhere by the roadside under apple–trees on the edge of a field. Other fields stretched away on our right and left to a border of woodland and a village steeple. All around was noonday quiet, and the sober disciplined landscape which the traveller's memory is apt to evoke as distinctively French. Sometimes, even to accustomed eyes, these ruled–off fields and compact grey villages seem merely flat and tame; at other moments the sensitive imagination sees in every thrifty sod and even furrow the ceaseless vigilant attachment of generations faithful to the soil. The particular bit of landscape before us spoke in all its lines of that attachment. The air seemed full of the long murmur of human effort, the rhythm of oft–repeated tasks, the serenity of the scene smiled away the war rumours which had hung on us since morning.

All day the sky had been banked with thunder–clouds, but by the time we reached Chartres, toward four o'clock, they had rolled away under the horizon, and the town was so saturated with sunlight that to pass into the cathedral was like entering the dense obscurity of a church in Spain. At first all detail was imperceptible; we were in a hollow night. Then, as the shadows gradually thinned and gathered themselves up into pier and vault and ribbing, there burst out of them great sheets and showers of colour. Framed by such depths of darkness, and steeped in a blaze of mid–summer sun, the familiar windows seemed singularly remote and yet overpoweringly vivid. Now they widened into dark–shored pools splashed with sunset, now glittered and menaced like the shields of fighting angels. Some were cataracts of sapphires, others roses dropped from a saint's tunic, others great carven platters strewn with heavenly regalia, others the sails of galleons bound for the Purple Islands; and in the western wall the scattered fires of the rose–window hung like a constellation in an African night. When one dropped one's eyes form these ethereal harmonies, the dark masses of masonry below them, all veiled and muffled in a mist pricked by a few altar lights, seemed to symbolize the life on earth, with its shadows, its heavy distances and its little islands of illusion. All that a great cathedral can be, all the meanings it can express, all the tranquilizing power it can breathe upon the soul, all the richness of detail it can fuse into a large utterance of strength and beauty, the cathedral of Chartres gave us in that perfect hour.

It was sunset when we reached the gates of Paris. Under the heights of St. Cloud and Suresnes the reaches of the Seine trembled with the blue–pink lustre of an early Monet. The Bois lay about us in the stillness of a holiday evening, and the lawns of Bagatelle were as fresh as June. Below the Arc de Triomphe, the Champs Elysees sloped downward in a sun–powdered haze to the mist of fountains and the ethereal obelisk; and the currents of summer life ebbed and flowed with a normal beat under the trees of the radiating avenues. The great city, so made for peace and art and all humanest graces, seemed to lie by her river–side like a princess guarded by the watchful giant of the Eiffel Tower.

The next day the air was thundery with rumours. Nobody believed them, everybody repeated them. War? Of course there couldn't be war! The Cabinets, like naughty children, were again dangling their feet over the edge; but the whole incalculable weight of things–as–they–were, of the daily necessary business of living, continued calmly and convincingly to assert itself against the bandying of diplomatic words. Paris went on steadily about her mid–summer business of feeding, dressing, and amusing the great army of tourists who were the only invaders she had seen for nearly half a century.

All the while, every one knew that other work was going on also. The whole fabric of the country's seemingly undisturbed routine was threaded with noiseless invisible currents of preparation, the sense of them was in the calm air as the sense of changing weather is in the balminess of a perfect afternoon. Paris counted the minutes till the evening papers came.

They said little or nothing except what every one was already declaring all over the country. "We don't want war— mais it faut que cela finisse!" "This kind of thing has got to stop": that was the only phase one heard. If diplomacy could still arrest the war, so much the better: no one in France wanted it. All who spent the first days of August in Paris will testify to the agreement of feeling on that point. But if war had to come, the country, and every heart in it, was ready.

At the dressmaker's, the next morning, the tired fitters were preparing to leave for their usual holiday. They looked pale and anxious—decidedly, there was a new weight of apprehension in the air. And in the rue Royale, at the corner of the Place de la Concorde, a few people had stopped to look at a little strip of white paper against the wall of the Ministere de la Marine. "General mobilization" they read—and an armed nation knows what that means. But the group about the paper was small and quiet. Passers by read the notice and went on. There were no cheers, no gesticulations: the dramatic sense of the race had already told them that the event was too great to be dramatized. Like a monstrous landslide it had fallen across the path of an orderly laborious nation, disrupting its routine, annihilating its industries, rending families apart, and burying under a heap of senseless ruin the patiently and painfully wrought machinery of civilization…

That evening, in a restaurant of the rue Royale, we sat at a table in one of the open windows, abreast with the street, and saw the strange new crowds stream by. In an instant we were being shown what mobilization was—a huge break in the normal flow of traffic, like the sudden rupture of a dyke. The street was flooded by the torrent of people sweeping past us to the various railway stations. All were on foot, and carrying their luggage; for since dawn every cab and taxi and motor—omnibus had disappeared. The War Office had thrown out its drag–net and caught them all in. The crowd that passed our window was chiefly composed of conscripts, the mobilisables of the first day, who were on the way to the station accompanied by their families and friends; but among them were little clusters of bewildered tourists, labouring along with bags and bundles, and watching their luggage pushed before them on hand–carts—puzzled inarticulate waifs caught in the cross–tides racing to a maelstrom.

In the restaurant, the befrogged and red–coated band poured out patriotic music, and the intervals between the courses that so few waiters were left to serve were broken by the ever–recurring obligation to stand up for the Marseillaise, to stand up for God Save the King, to stand up for the Russian National Anthem, to stand up again for the Marseillaise. " Et dire que ce sont des Hongrois qui jouent tout cela!" a humourist remarked from the pavement.

As the evening wore on and the crowd about our window thickened, the loiterers outside began to join in the war–songs. " Allons, debout! "—and the loyal round begins again. "La chanson du depart" is a frequent demand; and the chorus of spectators chimes in roundly. A sort of quiet humour was the note of the street. Down the rue Royale, toward the Madeleine, the bands of other restaurants were attracting other throngs, and martial refrains were strung along the Boulevard like its garlands of arc–lights. It was a night of singing and acclamations, not boisterous, but gallant and determined. It was Paris badauderie at its best.

Meanwhile, beyond the fringe of idlers the steady stream of conscripts still poured along. Wives and families trudged beside them, carrying all kinds of odd improvised bags and bundles. The impression disengaging itself from all this superficial confusion was that of a cheerful steadiness of spirit. The faces ceaselessly streaming by were serious but not sad; nor was there any air of bewilderment—the stare of driven cattle. All these lads and young men seemed to know what they were about and why they were about it. The youngest of them looked suddenly grown up and responsible; they understood their stake in the job, and accepted it.

The next day the army of midsummer travel was immobilized to let the other army move. No more wild rushes to the station, no more bribing of concierges, vain quests for invisible cabs, haggard hours of waiting in the queue at Cook's. No train stirred except to carry soldiers, and the civilians who had not bribed and jammed their way into a cranny of the thronged carriages leaving the first night could only creep back through the hot streets to their hotel and wait. Back they went, disappointed yet half–relieved, to the resounding emptiness of porterless halls, waiterless restaurants, motionless lifts: to the queer disjointed life of fashionable hotels suddenly reduced to the intimacies and make–shift of a Latin Quarter pension. Meanwhile it was strange to watch the gradual paralysis of the city. As the motors, taxis, cabs and vans had vanished from the streets, so the lively little steamers had left the Seine. The canal–boats too were gone, or lay motionless: loading and unloading had ceased. Every great architectural opening framed an emptiness; all the endless avenues stretched away to desert distances. In the parks and gardens no one raked the paths or trimmed the borders. The fountains slept in their basins, the worried sparrows fluttered unfed, and vague dogs, shaken out of their daily habits, roamed unquietly, looking for familiar eyes. Paris, so intensely conscious yet so strangely entranced, seemed to have had curare injected into all her veins.

The next day—the 2nd of August—from the terrace of the Hotel de Crillon one looked down on a first faint stir of returning life. Now and then a taxi–cab or a private motor crossed the Place de la Concorde, carrying soldiers to the stations. Other conscripts, in detachments, tramped by on foot with bags and banners. One detachment stopped before the black–veiled statue of Strasbourg and laid a garland at her feet. In ordinary times this demonstration would at once have attracted a crowd; but at the very moment when it might have been expected to provoke a patriotic outburst it excited no more attention than if one of the soldiers had turned aside to give a penny to a beggar. The people crossing the square did not even stop to look. The meaning of this apparent indifference was obvious. When an armed nation mobilizes, everybody is busy, and busy in a definite and pressing way. It is not only the fighters that mobilize: those who stay behind must do the same. For each French household, for each individual man or woman in France, war means a complete reorganization of life. The detachment of conscripts, unnoticed, paid their tribute to the Cause and passed on…

Looked back on from these sterner months those early days in Paris, in their setting of grave architecture and summer skies, wear the light of the ideal and the abstract. The sudden flaming up of national life, the abeyance of every small and mean preoccupation, cleared the moral air as the streets had been cleared, and made the spectator feel as though he were reading a great poem on War rather than facing its realities.

Something of this sense of exaltation seemed to penetrate the throngs who streamed up and down the Boulevards till late into the night. All wheeled traffic had ceased, except that of the rare taxi–cabs impressed to carry conscripts to the stations; and the middle of the Boulevards was as thronged with foot–passengers as an Italian market–place on a Sunday morning. The vast tide swayed up and down at a slow pace, breaking now and then to make room for one of the volunteer "legions" which were forming at every corner: Italian, Roumanian, South American, North American, each headed by its national flag and hailed with cheering as it passed. But even the cheers were sober: Paris was not to be shaken out of her self–imposed serenity. One felt something nobly conscious and voluntary in the mood of this quiet multitude. Yet it was a mixed throng, made up of every class, from the scum of the Exterior Boulevards to the cream of the fashionable restaurants. These people, only two days ago, had been leading a thousand different lives, in indifference or in antagonism to each other, as alien as enemies across a frontier: now workers and idlers, thieves, beggars, saints, poets, drabs and sharpers, genuine people and showy shams, were all bumping up against each other in an instinctive community of emotion. The "people," luckily, predominated; the faces of workers look best in such a crowd, and there were thousands of them, each illuminated and singled out by its magnesium–flash of passion.

I remember especially the steady–browed faces of the women; and also the small but significant fact that every one of them had remembered to bring her dog. The biggest of these amiable companions had to take their chance of seeing what they could through the forest of human legs; but every one that was portable was snugly lodged in the bend of an elbow, and from this safe perch scores and scores of small serious muzzles, blunt or sharp, smooth or woolly, brown or grey or white or black or brindled, looked out on the scene with the quiet awareness of the Paris dog. It was certainly a good sign that they had not been forgotten that night.

II

WE had been shown, impressively, what it was to live through a mobilization; now we were to learn that mobilization is only one of the concomitants of martial law, and that martial law is not comfortable to live under—at least till one gets used to it.