Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Fox Chapel Publishing

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

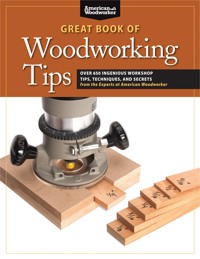

World's biggest collection of reader-written, shop-tested, photo-illustrated woodworking tips and techniques. One, two or three to a page. 730 total, more available in recent issues.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 449

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

GREAT BOOK OF

Woodworking Tips

GREAT BOOK OF

Woodworking Tips

OVER 650 INGENIOUS WORKSHOP TIPS,TECHNIQUES, AND SECRETS

from the experts at American Woodworker

Introduction by Randy Johnson

Editor, American Woodworker Magazine

Published by Fox Chapel Publishing Company, Inc., 903 Square Street, Mount Joy, PA 17552, 717-560-4703, www.FoxChapelPublishing.com.

© 2012 American Woodworker. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without written permission. Readers may create any project for personal use or sale, and may copy patterns to assist them in making projects, but may not hire others to mass-produce a project without written permission from American Woodworker. The information in this book is presented in good faith; however, no warranty is given nor are results guaranteed. American Woodworker Magazine, Fox Chapel Publishing and Woodworking Media, LLC disclaim any and all liability for untoward results.

American Woodworker, ISSN 1074-9152, USPS 738-710, is published bimonthly by Woodworking Media, LLC, 90 Sherman St., Cambridge, MA 02140, www.AmericanWoodworker.com.

ISBN: 978-1-56523-596-0

Publisher’s Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Great book of woodworking tips : over 650 ingenious workshop tips, techniques, and secrets from the experts at American Woodworker / introductions by Randy Johnson, editor, American Woodworker.--East Petersburg, PA : Fox Chapel Publishing, c2012.

p. ; cm.

ISBN: 978-1-56523-596-0 ; 1-53523-596-7

1. Woodwork--Handbooks, manuals, etc. 2. Woodwork--Amateurs’ manuals. 3.Woodwork--Technique. 4. Woodwork--Equipment and supplies. I. Johnson, Randy. II. American woodworker.

TT185 .G74 2012

684/.08--dc23 1204

To learn more about the other great books from Fox Chapel Publishing, or to find a retailer near you, call toll-free 800-457-9112 or visit us at www.FoxChapelPublishing.com.

We are always looking for talented authors. To submit an idea, please send a brief inquiry to [email protected].

Printed in Singapore

Fifth printing

Because working with wood and other materials inherently includes the risk of injury and damage, this book cannot guarantee that creating the projects in this book is safe for everyone. For this reason, this book is sold without warranties or guarantees of any kind, expressed or implied, and the publisher and the author disclaim any liability for any injuries, losses, or damages caused in any way by the content of this book or the reader’s use of the tools needed to complete the projects presented here. The publisher and the author urge all readers to thoroughly review each project and to understand the use of all tools before beginning any project.

Contents

Introduction

Bandsaw

Cabinet Making

Chop Saw

Clamps & Clamping

Drill Press

Electricity & Batteries

Finishing

Glue & Gluing

Hardware

Joinery Tricks

Jointer-Planer

Turning

Measuring & Marking

Plate-Joiner

Router

Sanding

Sharpening

Storing Tools & Supplies

Storing Wood

Tablesaw

Tool Smarts

Vise

Wood

Workbench

Introduction

It’s about the aha!

Everyone loves a clever workshop tip. An ingenious solution to a vexing problem brings an aha! to the lips, and with it the resolve to try the trick for oneself, or perhaps to go one better by creating an improvement. Or, if the shop tip is obvious, we salute with a slap to the forehead, wondering why we couldn’t have thought of that for ourselves. But we didn’t, and that’s one reason why woodworkers treasure collections such as this book.

The other reason, of course, is wrapped up in today’s workshop reality. It’s not like it was in Grandpa’s day, when skills and workshop practices were passed from master to apprentice and father to son. This is the era of the amateur craftsman, mostly self-taught, working alone in his or her home workshop, and most likely without much contact with other woodworkers. In lieu of Grandpa, we rely on woodworking magazines to provide this all-important sharing of information and shine a light on the conundrums that dog the path to prowess. Every magazine and journal in the field boasts a tips column, largely driven by the readers themselves and their urge to share hard-earned knowledge. Along with shop tips, readers frequently ask good questions, giving the editors the additional challenge and opportunity of finding and presenting equally good answers.

It’s often said that skill has two components: know-what, plus know-how. You have to know what to do, as well as how to do it. It’s not always easy to glean both components from the printed page, but a sharp photograph certainly does help. Photography is where this collection of workshop tips really shines. Since 1999, editors at American Woodworker magazine have invested heavily in creating clear photo illustrations for reader-submitted tips and questions. When it’s only a drawing, you’re never quite sure about the underlying reality. But the photo removes that uncertainty, making the answer clear on the page.

We’ve emphasized photo illustrations in this huge collection of workshop wisdom. I’m personally grateful to my predecessors and colleagues for their determination to grace each chunk of solid advice with photographic clarity. Our team certainly has enjoyed gathering, illustrating and organizing this priceless information. We hope you enjoy the succession of aha! moments that you’re sure to receive as you turn these pages.

—Randy Johnson, editor-in-chief,American Woodworker magazine

Bandsaw

New Bandsaw Tires

My bandsaw has developed tracking problems to the point that the blade won’t stay on the wheel. I checked everything and can’t seem to clear up the problem. What’s going on here?

Because these problems developed over time, I suggest you check your tires. The tires on your bandsaw provide traction for the blade and, like the tires on your car, they wear out and the rubber degrades with time. A new set of tires will likely put your saw back on track.

“Obvious signs of worn tires are cracks and tears,” explains Peter Perez, president of Carter Products Inc., a bandsaw accessory manufacturer. “A good wear test is to sink a fingernail into the tire. A good tire will rebound with no visible mark on it. If your fingernail leaves an impression, it’s time to replace the tire.”

It’s easier to replace the tires with the wheel removed from the saw. Taper the end of a dowel, clamp it in a vise, and set the wheel on it. We recommend replacing both rubber tires with urethane tires. Urethane offers two big advantages: It lasts longer and it doesn’t require adhesive to install. Clamp the new tire on the wheel and stretch the tire over the rim. Urethane tires can be made more flexible by soaking them in hot water before you put them on the wheels.

Spring Clamp Blade Storage

I like to keep my bandsaw blades on the wall next to my saw. To save space, I fold them into coils. The trouble comes when I hang the coiled blade on a peg or nail. I’ve had the blades suddenly come uncoiled and spring off the wall! That’s unpleasant and potentially dangerous. I tried using twist ties, but they wore out quickly and it was a pain having to tie up and untie the blade every time I used it.

I came up with this handy hanger made with a 2x4 and some very small spring clamps. I notched the edge of the 2x4 with a dado blade and screwed a spring clamp into each notch. Now when I go to change blades, all I have to do is squeeze the spring clamp to release the blade.

Can a 2x4 Dull a Blade?

After resawing some pine 2x4s, my bandsaw blade smoked and seemed mighty dull. How can that be?

Chances are your blade wasn’t dull at all. It’s teeth were probably coated with pine pitch, which you should remove with blade cleaner. Other woods, such as cherry, also deposit pitch on bandsaw blades.

Like any sawblade, a bandsaw blade’s teeth won’t cut properly if they’re caked with pitch. Pitch fills in the clearances necessary for the blade to cut with a minimum of friction. This makes the blade run hotter, which creates even more buildup. Blade cleaner removes all traces of pitch, making your blade feel much sharper. You should remove the blade for cleaning to avoid potentially damaging your wheel’s tires.

Tooth with pitch buildup

Tooth after cleaning

Clean Bandsaw Tires

My bandsaw tires have a buildup of pitch and sawdust that seems to be embedded right into the rubber. What’s the best way to clean my tires?

An excessive buildup of sawdust and pitch on your tires can lead to tracking problems, so it’s a good idea to clean them periodically.

Start by unplugging your machine. Then remove the blade and tilt the table out of the way. You’ll find the buildup to be much worse on your lower tire where sawdust tends to get trapped under the blade as it travels around the wheel. Use some 120-grit sandpaper or synthetic steel wool and a light touch to clean the wheel as you turn it by hand.

Disposable Guide Blocks

I’ve bandsawed hundreds of puzzle pieces using very small blades. I gave up on the steel guide blocks that came with my saw because when those little blades came in contact with the blocks, they’d dull right away. And, when I wanted to back out of a cut, the blade would pop out of the blocks.

Now I make my own guide blocks from scraps of hardwood. My blades last longer and don’t pop out or wander because they’re trapped between the wooden blocks. The blocks wear, but it’s so easy to just re-cut their ends or make new ones altogether.

With the bandsaw unplugged, I install the new blocks by pushing them toward the blade until they’re lightly touching it. Then I lock the blocks in place and spin the upper blade wheel to make sure they don’t drag on the blade.

Align Bandsaw Wheels

I’ve tried everything to get good resaw results on my bandsaw, but the blade still wanders. What gives?

If you use a sharp blade designed for resawing, compensate for drift angle, and set the proper tension and still get bad results resawing, there’s only one other possibility: Your wheels need alignment. Pop the hood (well, the wheel covers) on your saw and put a straightedge across the rim of both wheels (Photo 1). If there’s a gap, your wheels are not operating in the same plane.

Misaligned wheels are a problem for bandsaws with crowned wheels. If your saw is 16 in. or smaller, chances are it has crowned wheels. A crowned wheel has a slight hump where the blade rides. The crown is designed to force the blade toward the center of the wheel and aid in tracking the blade. If the two crowned surfaces are not in the same plane, they pull against each other, robbing the saw of power and accuracy.

Fortunately, the problem is easy to fix on most saws. First, measure the misalignment (Photo 2). Next, remove the blade and the wheel and apply the appropriate shim(s) (Photo 3). Most saws have thin washers behind each wheel. You may find removing the stock washer and replacing it with a thicker one is just the ticket.

Reattach the wheel and give your saw a spin.

Note: Some saws have an adjustable bottom wheel. Just loosen the setscrew and slide the bottom wheel in or out the appropriate amount.

Check the wheel alignment with your resaw blade mounted and tensioned. It may be necessary to adjust the tracking of the upper wheel to make the faces of both rims parallel.

Measure the gap with a ruler calibrated to at least 1⁄32 in. or with a dial caliper.

Add or replace washers behind the wheel to achieve alignment. For small adjustments, use metal shim stock or metal dado blade shims behind the washer.

Hassle-Free Blade Mounting

I don’t know how many times I’ve struggled to put on a bandsaw blade. When I get it placed on one wheel, it just pops off the other. My solution? I temporarily hold the blade on the top wheel with spring clamps. Then I thread the blade through the guides and onto the bottom wheel. I crank the tension lever, remove the clamps and, sure as Bob’s your uncle, I’m ready to go.

Bandsaw Table Lock

Before I installed this device, I couldn’t lock my bandsaw’s table securely enough for resawing. If I banged a heavy board on the outboard side, the table would always tip out of adjustment. Now the table stays fixed at 90 degrees.

After removing the table, I drilled and tapped two ¼-in. holes and bolted on a 3-in. length of angle iron with a slot cut in the long leg. After reinstalling the table and locking it perpendicular to the blade, I used this slot to locate and drill another ¼-in hole in the saw casting. I tapped this hole and installed a length of threaded rod, which I locked into place by tightening a nut against the frame. To lock the top at 90 degrees, I installed two additional nuts and a washer underneath the angle. When I want to tilt the table, I just remove the knob and its washer.

Folding Bandsaw Blades

I once saw someone fold a bandsaw blade for easier storage—how was that done?

Folding a bandsaw blade can be a bit intimidating when you first attempt it. Armed with sharp teeth and a spring-like tension, the blade deserves respect. At the same time it’s an easy trick for entertaining your non-woodworking friends!

Be sure to wear leather gloves and eye-protection. Stand behind the open blade with the teeth pointing away from you. With one foot, gently step on the blade just enough to keep it secure to the floor (if your floor is cement, use a piece of plywood to protect the blade). With the palms of your hands facing away from you, grasp the back of the blade at two and ten o’clock. Your thumbs should be pointed away from you (Photo 1). With a firm hold on the blade, roll your wrists inward so your thumbs end up pointing toward each other (Photo 2). At this point you will feel the resistance in the blade give way. Gently push the folding blade toward the floor as you lift your foot off the blade (Photo 3).

It may feel awkward at first but after a few tries you’ll be folding blades with the best of them.

Speedy Blade Tensioning

Changing bandsaw blades used to be a pain, because my bandsaw doesn’t have a quick-release blade-tensioning mechanism. I finally got tired of hand-cranking, so I replaced the tensioning rod with a ⅜-in. threaded rod. I locked two nuts against each other on top of the rod, making sure their faces lined up. Now a 9⁄16-in. socket operates the tensioning system and only my trigger finger gets tired.

Friction-Free Resaw Fence

Resawing a board is tricky. Most blades drift, so that you must angle the board to get a straight cut. Standard bandsaw fences can’t be angled to compensate for drift, so many folks use a single-point fence instead, like this one. The point on my fence is a tall stack of machine bearings, which gives me effortless, resistance-free cutting.

To build the fence, you’ll need a 5⁄16" steel rod, 5⁄16" i.d. bearings, 5⁄16" i.d. washers, a base 6" to 8" wide and as long as the depth of your saw’s table, an upright (its height depends on your saw’s capacity), and a hardwood cap to house the steel rod and hold the bearings in place. The steel rod and washers are available at any hardware store for a few bucks or try an auto parts or surplus store; the exact i.d. and o.d. of the bearings aren’t particularly important.

Drill a 5⁄16" hole at the base’s point to house the steel rod’s bottom end. Position the hole to allow the bearings to overhang the point by ⅛". Glue and screw the upright to the base, ⅛" behind the bearings.

Insert the rod in the base’s hole and stack the bearings with a washer between each one. Insert the top end of the rod in the cap’s hole, and then screw the cap to the upright, making sure it’s positioned so the bearing stack is square to the saw’s table.

Bandsawing Inside Curves

This is a useful trick when bandsawing inside curves. It requires no marking and no special jig. First I cut a shallow slot in a piece of scrap and attach it to the bandsaw fence, as shown. The radius of the cut, “R,” is the same as the distance between the fence and the blade. The notch acts as a pivot point as the workpiece is rotated around the cut.

Pattern-Cut Finials

The traditional way to make a square finial on a bandsaw is to mark and cut the pattern on one side of the blank, then tape the offcut back on to the blank in order to guide the cuts on the adjacent side. This is difficult to do with an intricate pattern because it’s hard to keep the offcut in one piece.

I use a sled with a handle for steering it. First, I screw the finial blank to the sled (Photo 1). Next, I screw a pattern to the top edge of the sled and follow the pattern to cut the first side of the finial (Photo 2). Then I unscrew the finial, rotate it 90°, screw it back on the sled, and cut the next side (Photo 3). The sled’s side supports are an important safety feature—they keep the finial from being pulled down by the saw’s blade during the second cut.

Blade Pop-out

When cutting a shallow angle, my bandsaw blade won’t follow the line. When I approach the end of the line at the edge of the board, the blade pops out of the cut. What am I doing wrong?

A fresh, sharp blade shouldn’t have this problem, but even a moderate amount of use can dull a blade sufficiently to cause it to pop out. The best solution is to make a habit of beginning the cut at the shallow angle, as shown at left, rather than exiting from it. If your cut has a shallow angle at both ends, start from one end, stop halfway, back out slowly, and start again at the other end.

Zero-Clearance Bandsaw Table

I like to cut tenons with my bandsaw, but the little cutoffs tend to fall down in the space by the blade and get in the way or bind the blade. I found a slick fix. Tape a piece of thin cardboard (from something like a manila folder or old cereal box) to the table. The trimmings stay on top of the table and are easily pushed out of the way.

Bandsaw Offcut Tray

While sweeping up offcuts from around my bandsaw, I realized two things: First, I hate sweeping. Second, a dustpan-shaped tray attached to the bandsaw would catch most of the offcuts I was sweeping.

I made my tray from scraps of ½-in. plywood and ¼-in. hardboard. I fastened two pieces of ⅛-in. x 1-in. steel to the tray and bolted it to my saw through the rip fence mounting holes. In addition to catching offcuts, this tray also offers convenient storage when I’m cutting numerous small pieces.

Resaw Without Warp

I’ve had a few bad experiences with wood warping after I resaw. Is there any way to tell whether a board is a good candidate for resawing?

The warp you refer to is case-hardening. A case-hardened board looks like any other board but has internal stresses caused by improper drying techniques. These stresses lay hidden until resawing releases them causing the board to warp.

Unfortunately, there’s no way to visually tell if a board is case-hardened or not, but there is a simple test. Go in about 6-in. from the end of the board and cut a ¾-in.-thick section. Go to the bandsaw and cut out about one half of the width from the middle. If case-hardening is not present, the fork will remain stable. If there are internal stresses present, they will manifest themselves in forks that either pinch together (case-hardened) or bow outward (reverse case-hardened).

Slice Steel on Your Bandsaw

I’ve heard of a technique called friction-cutting that allows you to cut steel on a woodworking bandsaw. What is friction-cutting and does it really work?

Friction-cutting is used in industry for cutting iron-base metals, also called ferrous metals, such as steel. You can adopt the technology to your woodworking bandsaw to do limited cutting of ferrous metals in your home shop. Here’s how it works: Mount a metal-cutting blade in your bandsaw. The woodcutting bandsaw’s high speed—3,000 feet per minute (fpm)—will cause the blade to dull quickly when cutting steel (see photos, below). However, the friction generated by the dull teeth will heat the metal to molten red, allowing the blade to slice through the steel. It’s amazing when you first try it. You’ll feel some resistance before the metal reaches the molten stage, but once it does, you can cut ⅛-in.-thick steel as though it were 1-in.-thick oak. I tried this in my own shop and had great results in steel ⅛ in. or thinner. Thicker metal diffuses too much heat so the metal doesn’t become hot enough to melt.

Friction-cutting on a woodworking bandsaw requires a few precautionary measures. Sparks fly using this method, so be sure to vacuum up all the saw dust in and around your saw beforehand. Also, the blade can be quite hot after continuous cutting, so keep your saw running but give the blade a break from cutting from time to time to let it cool. Otherwise the rubber tire on the wheel could melt. We recommend using ceramic blocks or the stock metal-guide blocks that came with the saw.

CAUTION Be sure to vacuum the dust from your machine before trying this procedure and disconnect dust-collection hoses from the saw.

Cutting steel at high woodcutting speeds turns a new metal-cutting blade into a dull but effective friction-cutting blade that can cut up to ⅛-in.-thick steel.

Cabinet Making

Better Drawer Sides

I like using ½-in. birch plywood for drawer sides because it’s so inexpensive, but when I rout dovetails sometimes it chips out like crazy. For a cleaner cut, should I be using solid wood instead?

No, you can stick with plywood, but switch to a different type, such as Baltic birch or ApplePly. Technique may not be the problem; it could be the material.

Most standard birch plywood has very thin face veneers glued to three thicker layers of softwood or utility hardwood veneers. These inner layers could contain rough areas, knots, voids and splits. When you hit those areas with a router, the result is chip-out.

Baltic birch and ApplePly are made from many more layers of thinner veneers. The inner veneers of both of these high-density plywoods are very smooth, and the greater number of thin inner plies makes chip-out much less likely.

The top edges of your drawers will look better, too, because there are fewer and smaller voids in high-density plywood. You won’t have nearly as many unsightly holes to fill.

Baltic birch is a generic term for imported plywood with birch faces and birch-core veneers. ApplePly is a trade name for one domestic manufacturer’s plywood with maple faces and birch- or alder-core veneers.

Baltic birch is available at many lumber dealers in various thicknesses, but it only comes in 5-ft. by 5-ft. pieces (about $25 for one sheet of ½ in.). One annoying problem: a whole sheet may not fit into the back of your truck or van without cutting first. ApplePly also comes in a variety of thicknesses and is made in standard 4x8 sheets (about $60 for one sheet of ½ in.).

A Bead in any Board

I wanted an antique beadboard look for my cabinet doors, but stock beadboard didn’t work out with my door size. Here’s what I came up with: I glued up a solid door and cut 3⁄16-in. x 3⁄16-in. dadoes at each glue joint. Then I chamfered the edges with a sanding block (or you could use a plane). Finally, I ran a thin bead of glue in the bottom of the dadoes and laid in 3⁄16-in. dowels. Could it be any simpler? Now I can have any width beadboard I need and I’m not limited to the wood species available at the lumberyard. I have a few more ideas to try, like using rope instead of dowels.

Good-Looking Panels

Nothing makes a cabinet look worse than door panels with unattractive grain that runs at weird angles. It pays to be picky about grain direction, even if it means wasting some plywood.

After assembling your door frames without glue, slide them around on the sheet of plywood until they frame attractive panels. Look for symmetrical grain patterns that you can center. Avoid patterns that run off one side.

I try to find grain that resembles mountains or cathedral arches. These A-shaped patterns make doors and cabinets appear taller and more graceful. Tight grain patterns, where the early and late growth is closely spaced, usually look better than patterns with wide grain.

Mark your good-looking panels by tracing around the inside of the door frames. Cut out the traced panels at least ½ in. larger on all four sides. Then trim them to fit the frames. Use the ugly plywood that’s left over for jigs or in other places where appearance doesn’t matter.

Beautiful Button Knobs

As a kid, I used to play with my grandmother’s button box every time we visited. I loved all those bright, shiny colors! Now that I’ve inherited her treasure hoard, I found a way to display these beautiful antiques on a sewing cabinet I made for my wife. Old buttons make fascinating knobs.

I turn or buy a set of wooden knobs and then drill out the centers of the knobs with a Forstner bit. I finish the knob and epoxy the button into the recess. Of course, new buttons work fine, too, and are easier to buy in a complete set.

Jazzed-Up Drawer Fronts

When I told my wife I was going to build her new kitchen cabinets she was delighted. I really surprised her when I dressed up the drawers with a little carving. It wasn’t that hard either and I only used one carving tool; a V-gouge. It sure jazzes up the kitchen!

Secure Knobs

I’ll never forget the time I tried to yank open a stuck drawer on my homemade dresser and ended up holding only the knob! I’d pulled the knob right off the screw. Determined to solve this problem, I went to my lathe and designed a knob that’ll never come off. As a bonus for the extra work, my two-part knob combines the ease of turning an end-grain knob and the beautifully grained top of a face-grain knob.

I removed the spurs from a standard T-nut with a pair of pliers and epoxied it into the base of the knob. I made a face-grain cap for the knob with a plug cutter installed in my drill press, epoxied it into a recess above the T-nut, and turned it smooth. When the cap is made from a highly figured contrasting wood, you’ve got a beautiful knob that’ll always remain firmly attached to your drawer.

Easy Drawer Dividers

Help! The junk drawer in our kitchen is out of control! I have trouble finding anything in there. Is there a simple way to add dividers to my kitchen drawers without taking them apart?

You bet! Here’s a way to control the clutter in less time than it takes to find the potato peeler.

To make the brackets that hold the dividers in place, groove the edge of a ¾-in.-thick board on your router table and round over the outside edges. Then rip the grooved edge off the board and crosscut to length. I like to attach the brackets with double-faced tape or a little hot-melt glue. That way you can reposition them to suit your ever-changing collection of kitchen junk.

Worn Drawers

I’ve noticed in some antique chests of drawers that the pine drawer sides are really worn. I want to build a chest of drawers meant for daily use but don’t want the drawers to wear away before my grandchildren get to use it. Is there a way to build better, long-lasting drawers?

Yes, there is. Furniture makers often used wood that was fairly soft for drawer sides because it was easy to work with. These sides wore away because the pine couldn’t handle the repeated rubbing of soft wood on soft wood. (As a cure, some Shaker cabinetmakers even tried tapering the drawer sides to make a wider bearing surface, as shown above.) Sides made from a soft wood are still a good idea, but for the longest-lasting drawers, add a strip of wear-resistant wood only where needed: on the bottom of the drawer side.

Before building the drawer sides, glue a ¼-in. strip of a hard wood to the bottom of the drawer side blanks. Build the runners from the same wood.

Why not make the sides entirely from a hard wood? Here are three good reasons:

•Softer woods are less expensive.

•It’s much easier to cut dovetails in a soft wood.

•Soft woods usually weigh less, causing less wear.

Cabinet Jacks

I usually work alone, but when I install upper cabinets, I always enlist the help of two shop-made cabinet jacks. They’re steadier than an extra pair of hands. The jacks stand on the lower cabinets. To position and level the upper cabinets, I just turn two bolts in each jack.

The jacks are 15" tall and 12" deep. Make them from 2x4s, with 2x6 bases. In the jack’s top members, pound two ½" x 2" coupler nuts into tight-fitting holes. Thread a ½" x 6" full-thread hex-head bolt through each coupler nut and cap it with a rubber chair-leg tip.

Comfortable Dovetails

Like the majority of workbenches, mine is fine for planing but too low for cutting dovetails without prolonged stooping. My answer is to clamp a heavy backing board, as shown in the sketch, and clamp the workpiece to it. I usually tilt the work so half the dovetail-cutting lines are vertical and then, after sawing, tilt it the other way for the second set. A refinement is to draw layout lines on the backing board for reference.

Pin Board Marking Jig

My task: 28 kitchen drawers of different sizes, all with hand-cut dovetails. The thought of laying these out was overwhelming, so I designed a jig to simplify the process. To make the jig, carefully lay out and cut a piece of ¼" hardboard as if it were the pin board for the tallest drawer. Glue and nail the hardboard to a ¾" plywood backer. Fasten a stop on each side.

Place an actual pin board into the jig with the outside face against the backer board and one side against either stop. Clamp the whole thing into a vise and use a chisel to mark the end grain, defining the pins. Scribe a depth line, and use a square to mark saw lines and cut the dovetails as usual. Since my drawer heights and my dovetail spacing were in ½" increments, the jig worked for all the drawers.

Drawer Stop Screws

Making an inset drawer line up flush with the face of a cabinet can be fussy work. To make it easy, I just install two screws on the back of the drawer and turn them until the drawer’s front is perfectly aligned.

Tight Knobs

Drawer knobs that work loose and spin around drive me crazy. So instead of drilling a hole through the drawer front and screwing the knobs on from the back, I fasten them to a post that’s securely anchored in the drawer front. I drill a pilot hole two-thirds of the way through the drawer front and thread in a pan head sheet metal screw (these screws have sharp threads that really grip). I cut off the screw’s head and file the rough edges. Then I thread on the knob.

Chop Saw

Adjustable Chop Saw Stop

This handy stop grips tightly and is easy to adjust, so you can lock in crosscuts. A spacer the same thickness as the saw’s auxiliary fence is the key. Sandwiched between the two clamp faces, this spacer makes the stop fit the fence perfectly. Sandpaper affixed to the stop’s front face provides a secure grip.

Glue the spacer and front clamp face together, making sure their edges are flush. Then glue on the plywood top. Align the back clamp face flush with the glued-up front assembly and drill a ¼-in. hole through all three pieces. Glue sandpaper to the front clamp face. Install the carriage bolt, set it with a hammer and attach the knob. I mounted the knob on the back face so it would be out of the way. The top’s overhang keeps the back face from spinning as you tighten the knob.

Double-Duty Edge Guide

Instead of measuring for my circular saw’s offset each time I need to make a cut, I use a modified edge guide. I screwed two ¾" x ¾" x 12" hardwood blocks to the front and back clamp bars of the guide and clamped the guide to a board.

Next, I placed the saw’s base against the edge guide and made a cut through the blocks and the board. The end of each block now indicates exactly where the saw will cut. I just line up the end of one block with a pencil mark on the panel, clamp the guide, and turn on the saw.

I also routed a dado in the other end of the hardwood blocks, using the same method. Again, instead of measuring my router’s offset, I just position the dadoes in the blocks next to a pencil mark on the panel, and rout away.

Quick-Action Miter Saw Stop

I got tired of clamping a block to my miter saw fence every time I wanted to make a stop cut, so I made this adjustable quick-action stop. Unlike a spring clamp, once this baby’s clamped to the saw fence, it stays put!

My stop is based on a locking welding clamp I found at the hardware store for about $24; imported knock-offs cost a lot less. This weird-looking clamp has adjustable jaws and locks just like vise-grip pliers do.

First, I cut the front tongs from the clamp’s upper jaws. They’re hardened steel, so I used an angle grinder equipped with a cutting wheel. After cutting, I ground the surfaces flat. Then, using my drill press, I drilled holes for the screws.

For the clamp to work, the stop board must be ⅜ in. taller than the fence, because the clamp’s lower jaws have an offset “sweet spot.” Before mounting the clamp, I notched the stop board’s bottom corners to prevent sawdust buildup.

Doweling Jig Saw Stop

My doweling jig ended up in the junk drawer after I bought my biscuit joiner. I brought it out of retirement though, when I set up my chop saw bench. That old doweling jig has become a very useful saw stop. I simply clamp it to my 2x2 fence. I added a tape measure to the top of my fence, which makes setting the stop quick and accurate. It’s simple to remove the jig if I need to use it for doweling.

Sawing Aluminum

Can I cut aluminum with my chop saw?

Yes. Most carbide blades work fine for occasionally cutting aluminum, but we recommend using a special, non-ferrous metal-cutting blade (about $70) if you cut a lot of aluminum or brass. It’s safer to use than a standard blade because the geometry of the teeth makes it less likely to kick back when cutting a soft metal. And it will last longer than a standard blade because the teeth are made of a softer carbide.

No matter which blade you use, feed the saw about one-third slower than you do when cutting wood. Coating the blade with a regular dose of WD-40 (when the saw’s not running) prevents the gullets from clogging.

Flip-Up Miter-Saw Fence

I was so excited when I bought my sliding miter saw, until I realized how much bench space it took up. My Bosch needs a bench at least 38-in. deep. I also wanted an extension fence on both sides, but this made my benchtop almost unusable for other work. I fixed my problem by hinging the fences to the walls. Now when I want to use the benchtop for something else, I just flip up the fence. I hold it to the wall with a simple wooden turnbuckle.

Stop Block That Stays Put

When making repetitive cuts, I found that my stop block would shift. With a hardwood cutoff, a leftover piece of T-track, a ¼–20 hex head bolt and a jig knob, I constructed a stop block that doesn’t move and is super easy to adjust.

First, drill a hole in the saw’s fence, then groove the block for the T-track. Slide the head of the bolt into the T-track and insert the threaded end through the hole. Tighten the jig knob on the back of the fence, and the stop block doesn’t move!

One-Switch Chop Saw Station

I decked out my chop saw station with a shop vacuum for dust collection and a shop light so I can see where I’m cutting. It worked great except for one thing: I had to flip two switches just to make one cut. The solution was simple. I bought a power strip, with keyholes for mounting, for about $6 at the hardware store and plugged everything into that. Now when I want to make a cut, I flip a single switch on the power strip and my chop saw station springs to life. No more fumbling around.

Super Chop Saw Stop

This stop slides along a rail that’s screwed to the top of my chop saw fence, and I can lock it in any position. The hinged block is locked in the down position with a trunk latch. When not needed, the stop can be flipped up out of the way or removed altogether. The miter attachment is quickly installed with a single bolt and two wooden locking pins keep it from swiveling.

Zero-Clearance Miter Table

Here’s a dirt-simple but effective accessory for your miter saw. It eliminates tear-out, allows you to make precision cuts by aligning a pencil mark with the kerf, and provides room to screw or clamp a stop block anywhere along the fence.

Originally, I built this table for extra support when cutting long pieces. But it’s such a great addition that now I leave it on my saw all the time.

You could use ¾" stock, but I made my table from ½" plywood to minimize the decrease in my saw’s crosscut capacity. It can be any length you want. For stability, make the bed about 3" wider than the maximum length of the saw’s kerf.

Glue and screw the fence to the plywood bed at 90°. Screw the table’s fence to the saw’s fence, and you’re set.

Portable Miter Saw Station

I just don’t have room in my crowded shop for a permanent miter saw setup. Consequently, I designed this miter saw station to easily knock down when I’m not using it.

I started with an 8-ft. 2x12 that was flat and straight. (A couple of pieces of ¾-in.-thick plywood glued together would also work.) I routed a groove down the middle of the 2x12 for the metal T-track. Then I screwed my miter saw to a plywood carriage board, which I fastened to the T-track with T-bolts and knobs. This allows me to slide my saw to either end when cutting long boards. I added two sliding support brackets which are also attached with T-bolts and knobs. The brackets support the ends of my boards when I’m sawing. I added a flip-up stop to each bracket so I can make multiple parts of the same length. When I’m not using my miter saw station, I simply remove the saw and stand the 2x12 on end, secured against a wall. The whole setup cost me about $50.

Clamps & Clamping

Mobile Clamp Carousel

I’ve got a pile of K-body clamps that I use all the time. This clamp carousel guarantees they’re always close at hand. It stores 18 clamps in a 2-sq.-ft. space, and I can roll them right to the job.

My carousel consists of two ¾-in. plywood discs securely fastened to a center post by glue, screws and braces. The top disc has a 1½-in. square cutout in the center so it will slip over the post. Both discs are divided into 18 segments, each spanning 20 degrees. I cut notches for the clamp beams in the top disc and glued wedge-shaped spacers on the bottom disc to corral the clamp heads. The carousel rolls on five 3-in. swivel casters. To hold the clamps in place, I screwed a strip of plastic cut from a food-storage container around the edge of the top disc and cut a slit at each notch.

Cut Notches

Without notches on a mobile cart, one bump can send your clamps flying. The boards that you notch should be wide enough to fully support the clamps’ heads. The trick is to make the notches deep enough for a clamp’s head and wide enough so the clamp’s bar is easy to insert and remove.

To make half-round notches for pipe clamps, drill holes down the middle of a wide board. Rip through the center of the holes to make two support boards, each with half-round holes.

Make Big Brackets

These sturdy 12-in. x 16-in. brackets are great for storing lots of long, heavy clamps in a narrow space. The 2x4 brackets are wide enough for pipe and bar clamps. Use 2x6s to store K-body-style and deep-throated adjustable clamps.

Dado a 45-degree support board into each bracket. Screw the brackets to the cleats from the back, leaving 2-in. spaces between for the clamps’ bars. Then fasten the brackets to the wall.

Conduit Fits All the Shorties

If you have room for only one rack for your short clamps, build this one. It accommodates a wide variety of shapes—almost anything that has jaws. The rack even holds C-clamps and quick-release clamps, which usually have to be tightened to stay on a board for storage. Simply hook them over the metal conduit. Conduit is superior to using a wooden dowel rod because it is stiffer and more durable.

For most clamps, position the conduit 2 in. from the wall. Strategically locate a second length of conduit to support the bars of long clamps.

Metal Brackets Serve Double Duty

Got long clamps you want to keep handy? Use heavy-duty 12-in. shelf brackets. (They’re great for lumber, too.) This rack works well for long, heavy clamps because it stores them horizontally, making it easy to remove, use and return them. When you need one, simply pick it up and lay it down on your project. You won’t have to twirl or hoist them the way you would if you stored long clamps in a vertical rack.

Heavy-duty shelf brackets are available at home centers; the slotted standards come in short lengths for a dedicated clamp rack.

Double Duty Clamp Rack

One sure thing about clamps is that they’re never close enough when you need them. That’s why I devised this rolling rack. Its 4-in. locking swivel casters easily plow through sawdust and over cracks and power cords. To make this rack doubly useful, I designed it to work as an outfeed support for my tablesaw. Its 2x6 top inclines at a 5-degree angle so its top edge matches my tablesaw’s height.

I made the rack from 2x4s, a 2x6 and ⅝-in. electrical conduit. Drill 11⁄16-in. holes for the conduit in the doubled-up 2x4 rails, spaced to suit your clamp lengths. Then cut the conduit in 18-in. to 24-in. lengths as needed and install them. To keep the clamps from sliding off, cap the conduit support arms with rubber chair leg caps from the hardware store.

Mobile Clamp Rack

Tired of dragging clamps around my shop, I built this rack that brings them right to the job. It takes up only 21 x 32 in. of real estate and can handle 36 adjustable clamps and 12 4-ft. pipe clamps.

I assembled the side frames separately before screwing them together with gussets at the top and a plywood shelf at the bottom. I tapered the ends of the 1x4s at the top to fit. Before installing the 3-in. swivel casters, I glued on plywood pads to reinforce the corner joints.

Each frame consists of 2x4 and 2x6 rails screwed to 1x4 ends. I ripped the 2x6s in half to make the clamp rails. I staggered the top rails so the pipe clamp rail sits higher.

To make the half-round cutouts that hold the pipe clamps, I drilled centered holes in the 2x6 before I ripped it in half.

On the other frame, I cut slots in the rails for adjustable clamps. I cut the slots on my tablesaw, using my dado set and the miter gauge.

Throw ’Em in a Tub

Oddball clamps won’t become lost if you keep them together in a utility tub, which costs about $3 at a discount store. Tubs are a great way to store and transport spring clamps, C-clamps and small hand screws. Lidded tubs can even be stacked.

Clamp Blocks Plus

Bessey K-Blocks are great for holding K-clamps in position for glue-ups, but they’re also quite handy for other things. I milled hardwood strips the same dimensions as my K-clamps and use them to raise work pieces for stacked glue-ups. I also use the blocks and strips for pocket-hole assembly, so I don’t have to hang a joint over the edge of my workbench to clamp it. Shop-made blocks like these, made in maple, would work just as well.

Cauls Distribute Pressure

It’s not easy to get enough squeeze in the middle of a big box to force home dado or biscuit joints. Big cauls are the answer.

A caul is simply a thick, straight board. I make my cauls from stiff wood, such as hard maple, but any wood will do. The wider and thicker the caul, the less it flexes and the better it delivers pressure far from the clamps. I made a set of eight, each measuring 1¾ x 3 x 24 in., to have around the shop whenever I need them.

Stout cauls like these should provide plenty of pressure, but you can get extra pressure in the middle by inserting one or more shims (I use playing cards). You can also round or taper one of the caul’s edges from the middle to each end to create a crown. I do a dry run with cauls top and bottom, without shims, and place a straightedge on the cabinet to see whether the sides are flat. If one side bulges and needs more pressure in the center, I loosen the clamps, insert shims and retighten.

Another Angle on Flat Glue-ups

To keep panels from bowing under clamp pressure while gluing, I install lengths of angle aluminum on each end. I clamp the angle pieces just firmly enough to hold things in place. Then I tighten the pipe clamps. Unlike iron or steel, aluminum won’t leave black marks where it contacts squeezed-out glue. Unlike a wooden cleat, it won’t become glued to the panel.

Blocks Center Clamping Pressure

Uneven clamping pressure can easily draw offset joints, such as the one shown here, out of square. A block aligned with the joint properly directs the clamp’s pressure.

90-Degree Brackets Simplify Complex Clamping Jobs

Clamping together a cabinet with numerous shelves and rails can be a real pain. Shop-made 90-degree brackets allow assembling the cabinet one joint at a time and keep the joints square while you clamp the cabinet together.

Clamp Table

I don’t have room in my garage shop for a permanent clamp table, so I made this folding version from a leftover 2-ft.-wide sheet of ¾-in.-thick plywood. Folded, it’s less than 2 in. thick, so it stores neatly in a narrow space.

First, I crosscut the sheet to 60 in. in length. Then I made a rip cut to create the 16-in.-wide base.

Next, I drilled 1⅛-in.-dia. holes at 4-in. intervals down the middle of the remaining 8-in.-wide piece. Ripping this piece down the middle created two racks with half-round cradles for pipe clamps. I attached these racks to the base with screen hinges, which are flat on the outside, so they can be surface-mounted (I bought four 3-in. screen hinges for less than $4 at my local home center). I mounted the hinges on the inside of the racks, so the racks sit on the base when they’re open.

Friction-fit spreaders lock the racks in position during use. I made the spreaders 3 in. wide so they sit below the half–round clamp cradles. When the table folds for storage, wing nuts hold the spreaders on the base.

Box Beams Guarantee Flat Glue Ups

Made by gluing rails of equal width between two faces, box beams work like thick cauls to evenly distribute clamp pressure. They’re great for gluing veneered panels or torsion boxes.

Support Unwieldy Clamps

Without help, it’s tough to hold a long, heavy pipe clamp level while you draw it tight. By supporting one end, a spring clamp eliminates the need for help from extra hands.

Check Edge Joints With One Centered Clamp

Like dry-fitting a joint before you glue, this technique highlights imperfectly jointed boards that may otherwise be hard to see. Here, one slightly crowned edge causes a noticeable gap. Even if no gaps appear, test all the joints by lifting one board while lowering the other. If the boards move without resistance, the joint is too loose. Re-joint one or both boards and try again.

Clamp Jaw Binder

When I loosened my adjustable clamps to make minor adjustments, they frequently slipped all the way open. Sometimes my hand got whacked, sometimes the clamp fell and sometimes entire clamped-up assemblies crashed to the floor. Limiting the lower jaw’s travel with a rubber band solved the problem. Now I can easily adjust my clamps using one hand.

Clamp Traction Pads

My spring clamps wouldn’t work on an acute-angle joint I needed to clamp. Even though their jaws had swiveling pads, the clamps just slipped off.

Nothing worked to hold the clamps in place until I made my own traction pads by gluing strips of coarse abrasive together back to back. When the glue was dry, I cut the strips into squares and stuck them between the clamp pads and the wood.

Corner Clamp for Thick Stock

Thick stock is no problem with this quick clamping setup. Cut the notches so they line up with the center of the miter. This helps the joint come together evenly and reduces joint slippage when the handscrew clamp is tightened. A piece of folded sandpaper (180 or 220 grit) placed between the clamping boards and workpieces also helps.

Clamps by the Roll

Tape works wonders when it comes to clamping together small projects like jewelry boxes. Regular clamps can be cumbersome and simply too big and heavy. By contrast, masking tape, is easy to use. When you stretch the tape a little it exerts sufficient pressure for small projects. As always, make sure your project is square before setting it aside to dry.

Create Parallel Clamping Shoulders For Curved Shapes

Make custom clamping blocks by tracing and cutting the curved profiles. Then mark and cut clamping shoulders parallel to the joints. Be proactive: Self-hanging clamp blocks free both hands for clamping. trimmings stay on top of the table and are easily pushed out of the way.

Home-Made Deep Reach Clamps

Like most woodworkers, I never have enough clamps. Adding to a clamp collection is expensive, so when I needed some deep reach clamps, I made these auxiliary hardwood jaws. You can make them whatever size you like. The jaws are mortised to slide on the clamp’s bar. A stiff wood that resists splitting, like maple, is ideal.

Masking Tape Clamps Edgebanding

Thin stock doesn’t require lots of clamping pressure. Simply draw the tape across the edgeband and firmly down both sides of the panel guide, simply saw off the end. As long as your blade is set at 90 degrees to the table, you should get near-perfect results.

Make Short Clamps Go Long

You don’t need super-long clamps to clamp super-long glue-ups. Just gang your regular clamps together.

Knock-Off Blocks for Long Miters

Long miters are a nightmare to clamp, but adding temporary triangular blocks makes it a snap. The key is to use paper from a grocery bag. Dab some wood glue on both sides of the paper, stick the blocks wherever you need them and let the glue set overnight. When you’re done clamping, remove each block with a hammer blow. The paper creates a weak spot in the glue bond, so the blocks break away without damage to the wood. Use hot water to soften any paper or glue left on the wood, then scrape it away and sand as usual.

Paper Towel Pads Keep Corner Joints Clean

Here’s a trick for managing glue squeeze-out when you clamp dovetails or box joints: Face your clamp pads with paper towels. They absorb glue so it doesn’t soak deeply into the wood. After the glue has dried, the papered blocks knock off easily. Dampen any paper that remains on the joint. After about a minute it’ll scrub right off.