Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Fox Chapel Publishing

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

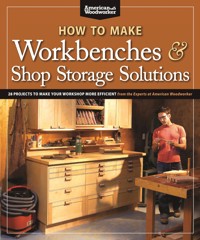

Everything you wanted to know about building a workbench, making outfeed tables for shop machines, making work tables and assembly tables, storage cabinets for tools, materials and supplies. Bonus: Build like an aircraft engineer, super-flat and strong with a torsion box workbench, assembly table, and alignment beams.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 242

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Published by Fox Chapel Publishing Company, Inc., 1970 Broad St., East Petersburg, PA 17520, 717-560-4703, www.FoxChapelPublishing.com

© 2011 American Woodworker. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without written permission. Readers may create any project for personal use or sale, and may copy patterns to assist them in making projects, but may not hire others to massproduce a project without written permission from American Woodworker. The information in this book is presented in good faith; however, no warranty is given nor are results guaranteed. American Woodworker Magazine, Fox Chapel Publishing and Woodworking Media, LLC disclaim any and all liability for untoward results.

American Woodworker, ISSN 1074-9152, USPS 738-710, is published bimonthly by Woodworking Media, LLC, 90 Sherman St., Cambridge, MA 02140, www.AmericanWoodworker.com.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2011006445

Print ISBN: 9781565235953

eISBN: 9781637411087

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

How to make workbenches and shop storage solutions.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN-13: 978-1-56523-595-3

ISBN-10: 1-56523-595-9

1. Workbenches. 2. Storage in the home. I. American woodworker.

TT197.5.W6H69 2011

684’.08--dc22

2011006445

To learn more about the other great books from Fox Chapel Publishing, or to find a retailer near you, call toll-free 800-457-9112 or visit us at www.FoxChapelPublishing.com.

Contents

What You Can Make

Workbench Projects

Dream Workbench

The Best $250 Workbench

Adjustable Workbench

Master Cabinetmaker’s Bench

How to Buy and Tune Vises

Assembly Tables

Building an Assembly Table

Adjustable Height Assembly Table

Heavy-Duty Folding Shop Table

Folding Work Table

Hardworking Horse and Cart

Double-Duty Shop Stool

Tool Storage

Dovetailed Tool Box

Hold-Everything Tool Rack

Small Tools Cabinet

Tool Cabinet

Hyperorganize Your Shop

Designs for the Hyper-Organized Shop

Flip-Top Tool Chest

Small Shop Solutions

Tips for Tool Storage

Materials Storage

Big Capacity Storage Cabinet

Modular Shop Cabinets

6 Storage Solutions You Can Build Into Any Cabinet

Flammables Cabinet

Simple, All-Purpose Shop Cabinets

Torsion Box: The Ultimate Workbench

Torsion-Box Workbench & Expandable Assembly Table

How to Build a Torsion Box

Torsion Beams

What You Can Make

These projects are notable for their ability to

MOVE

Dream Workbench

Heavy-Duty Folding Shop Table

Folding Work Table

HANG

Hold-Everything Tool Rack

Hyperorganize Your Shop

Designs for the Hyper-Organized Shop

Tips for Tool Storage

STAY FIRM

Dream Workbench

The Best $250 Workbench

Master Cabinetmaker’s Bench

How to Buy and Tune Vises

Heavy-Duty Folding Shop Table

Torsion Beams

HOLD

Dovetailed Tool Box

Small Tools Cabinet

Tool Cabinet

Big Capacity Storage Cabinet

Modular Shop Cabinets

6 Storage Solutions You Can Build Into Any Cabinet

Flammables Cabinet

Simple, All-Purpose Shop Cabinets

ADJUST

Adjustable Workbench

Building an Assembly Table

Adjustable Height Assembly Table

Hardworking Horse and Cart

Double-Duty Shop Stool

Flip-Top Tool Chest

Torsion-Box Workbench & Expandable Assembly Table

How to Build a Torsion Box

Workbench Projects

A work surface that’s lightweight, wobbly or lacks a proper woodworking vise is frustrating to use. On the other hand, a solid workbench provides the same benefits as a well-sharpened cutting tool: It promotes good results, and is a pleasure to use. If you’re looking to upgrade or add another bench to your shop, keep reading. The workbenches in the following chapter are designed especially for woodworking. They’re all stout, stable, strong and equipped with vises that making clamping easy and efficient. Even with a modest budget, you can build our sturdy and useful $250 workbench. If you want the fine furniture appearance of a traditional European-style workbench, consider the master cabinetmaker’s workbench. Its design, the result of years of refinement, will meet the needs of even the most demanding woodworkers. If you want a bench that also doubles as a storage cabinet, consider the benefits of our dream workbench; with lots of space for tools, it’s mobile and yet rock solid. Do you need a high or a low work surface? You can have it both ways with our adjustable workbench. Its special hardware allows you to make the top and the base almost any size you need.

by DAVE MUNKITTRICK

Dream Workbench

A MODERN BENCH THAT FEATURES STORAGE, STABILITY AND MOBILITY

Tired of working on a sheet of plywood thrown over a pair of sawhorses? Had it with rolling benches that wiggle and wobble? Hate running around your shop whenever you need a tool? Boy, do we have the bench for you.

Our dream bench starts with traditional workbench features like a thick top, a sturdy base, bench dogs and a pair of vises. Then we added tons of storage, an extra-wide top, and modern, cast-iron vises. Last but not least, we devised a simple method to make the bench mobile and still provide a rocksolid work platform.

Benefits

Tons of Easy-Access Storage

Full extension drawers and shelves keep your equipment organized and right at hand. There’s room for hand tools, power tools and all of their accessories. Plus no bending down and fishing through dark cabinet interiors for the tool you need.

You Name It, This Bench Can Clamp It Down

A traditional bench dog system secures your work for machining and sanding. The modern cast-iron vises are strong yet easier to install than traditional vises.

The generous overhanging top allows you to clamp anything from round tabletops to benchtop machines anywhere along the edge.

Extra-Wide, Heavy-Duty Top

This solid maple top can take a real beating. Plus it’s wide enough to double as an assembly table. If you only have room for one bench in your shop, this is it.

It’s Rock-Solid But Mobile

Under the base cabinet are six heavy-duty casters that make the bench easy to move. When you’re ready to use it, lift the edge of the bench with a pry bar and slip four ⅝-in.-thick, L-shaped support blocks underneath. This gives you a rock-solid feel and unlike locking casters, there’s no wobble or slippage.

Our bench is built to withstand generations of heavy use. Simple, stout construction absorbs vibration and can handle any woodworking procedure from chopping deep pocket mortises to routing an edge on a round tabletop.

The thick, butcher-block-style top is truly a joy to work on. We’ll show you how to surface this huge top without going insane trying to level 24 separate strips of glued-up hardwood. Our top doesn’t waste wood—even the offcuts are used.

Tools and Materials

If you go all out like we did you can expect to pay about $900 for materials. If you can’t swing that much dough all at once, don’t worry; you can build an equally functional version for about $450. How? Save $220 right off the bat by substituting common 2x4s for the maple top. We made several tops this way and they work great. Just be sure you dry your 2x4s to around 8 percent moisture content before you build. You can save $75 by skipping the expensive birch plywood and hardwood. Just stick with construction lumber. The inexpensive bench may not look as classy, but hey, it’s still a great workbench.

You could build adjustable shelves inside the cabinets instead of drawers and pullout trays. They’re less convenient, but it’ll save you another $110 in drawer slides.

The best thing is you can cut costs and still get a fully functional bench right away, even if you go with the least expensive options. When you’ve got the extra cash, you can always build the maple top or add the full-extension hardware.

Start the base cabinet by assembling three identical boxes with butt joints and screws. Make sure all the parts are square and the joints are flush. Use a flat area, like the top of your tablesaw, to help keep things in line.

Screw the three boxes together to create the cabinet base. Use clamps to hold the boxes flush and even.

Glue and clamp face frames to the cabinet. Start with the side frames. Then add the front face frame so it overhangs the bottom of the cabinet to form a lip for the 2x4 base you’ll build later.

Trim the face frame flush to the cabinet sides. Use a stop block at the top of the cabinet openings to prevent the router from cutting into the upper rail.

To build the bench you’ll need a tablesaw, planer, belt or orbital sander, a router and a circular saw. You’ll also want a flush-trim bit and a dado blade for your tablesaw.

Build the Cabinet

Cut the plywood parts for the three individual boxes (Parts D and E) and assemble them (Photo 1). The three boxes are joined to form the cabinet (Photo 2). Screw the two end pieces of birch plywood (H) to the cabinet, placing the screws where the face frame will cover them (Fig. A). Cut the plywood top (C) according to the actual measurements of your assembled cabinet and attach with screws. Do the same for the back (B).

Cut and assemble the three face frames (parts U through AA). Use the actual measurements of your cabinet to determine rail lengths. The face frames are built slightly oversize to give you a little wiggle room when gluing them to the carcase. The extra overhang will get trimmed off later. Clamp and glue the side frames first. Tack the frames down with a couple of brad nails so they don’t scoot around under clamping pressure. Use a flush-trim bit and a router to trim the side frames even with the plywood. Attach and trim the front face frame (Photos 3 and 4).

To mount the drawer and pull-out shelf slides, turn the cabinet on its back and use a square to mark centerlines. Use a simple T-square jig to align the slides so the screw holes are on the line (Photo 5).

Attach the drawer slides to the cabinet. A simple T-square jig positions the slide for quick installation. Stop blocks hold the slides ½ in. back from the front edge for the half-overlay doors. The doubled-up box sides automatically flush up with the 1 ½-in.-wide face frame so there’s no need to add blocks for the drawer slides.

Cut pieces for the benchtop, making them 2 in. longer than the finished top. Don’t toss the offcuts into the firewood pile. We’ll build them into the top so nothing goes to waste.

Cut dadoes for the bench dog holes in one of your benchtop pieces. Use a dado blade and a miter gauge with a long auxiliary fence to support the stock. The slots are marked on the top of the piece. It’s okay to eyeball each cut. Exact spacing of the holes is not critical.

Glue together the offcuts end to end. Clamp them between two fulllength pieces to keep them straight. This yields a few more strips for the top and uses up your offcuts. Waxed paper around the joint keeps the segmented strip from sticking to the full-length pieces. We used the back of the cabinet for a flat glue-up table.

The Top

This is the business end of your bench. You’ll want to take extra care in each step to ensure a flat, solid top. Start by roughcutting your top stock (EE) to length (Photo 6). Cut ¾ in. x ¾-in. dadoes for the bench dog (JJ) into the edge of one of the top pieces (Photo 7).

Before you start to glue up the top, make use of the offcuts. Just end glue them in a line to create a full-length piece (Photo 8). I know gluing end grain is a no-no, but all you want here is to hold the pieces together long enough to build them into the top. Each segmented piece will get properly edge-glued to other full-length pieces. The result is a strong top that doesn’t waste precious hardwood.

Here’s how to assemble the butcher-block top without facing a sentence of hard labor sanding. Glue up three 12-in. sections of the top on a flat surface. We flipped the cabinet face down and used the back for our glue-up (Photo 9). Each 12-in. section should start and end with a full-length piece. The segmented pieces can alternate with full-length pieces. Once the glue is good and dry (overnight is best), remove the top section from the clamps and scrape off any squeeze out.

Now you’re going to put your portable planer to the test. Each section gets planed down to 2½-in. thickness (Photo 10). Take light cuts for the sake of your planer, and to minimize tear-out. Try wetting the top’s surface before the last pass for the smoothest possible cut. Some minor tear-out is inevitable with a big glue-up like this. Remember it’s a workbench, not a museum piece.

Once all three sections are surfaced, you can glue them together (Photo 11). Do one at a time. This allows you to concentrate on keeping each joint perfectly level. Before you use any glue, dry clamp your sections to make sure the clamps can draw the joint tight. Even a slightly bowed section will be hard for clamps to pull straight. (See Oops! for a nifty fix.)

Once all the sections are glued together you’ll need to trim the ends to final length. Mark the ends of the top with a square. Continue the marks around the underside of the top as well. Set a circular saw for a 1½ -in.-deep cut and clamp a straightedge to the top so the saw cuts on the line. Make the first cut. Then flip over the top and set the straightedge for the second cut. Complete the cut and smooth the ends with a power sander.

Install the Vises

Installing the vises is pretty straightforward. We added a pair of non-marring wooden cheeks to the vise jaws first. The large face vise required a block (KK) to shim it down ⅛ in. below the top (Fig. A). We had to saw notches in the block and the bottom edge of the top to accommodate a pair of support ribs on the back of the vise.

Install the face vise on the top. Then glue a couple of strips to the front edge of the top so the edge is flush with the wooden cheek (Photo 12).

The smaller tail vise only needs a couple of washers to shim it down.

A simple, stout workbench that will last for generations

Figure A: Overall Exploded View (See Cutting List)

We used simple joinery and straightforward construction techniques to build this bench. Note that the front edge of the tail vise top support (DD) is cut flush with the front of the cabinet and the top corner is nipped back to allow clearance for the vise.

Detail 1: Bench Dog

Use straight-grained hardwood stock for your bench dog.

Glue eight strips together to form one 12-in. section of the top. Cauls keep the top pieces in alignment. The bench dog piece is placed second from the edge with the dadoes facing toward the front edge.

Plane each 12-in. section flat. Take light cuts and make sure your planer knives are sharp, to minimize tear-out. Outfeed support is essential when planing heavy stock like this.

Build the Base

Build the base flush with the bottom of the cabinet. Pick the straightest 2x4s you can find for the frame. If possible, we recommend starting out with 2x6s that have been dried to about 8-percent moisture content. Then joint and plane them to make straight and true 2x4s. Assemble the 2x4 frame with screws. A plywood base top (A) is fastened to the frame to finish the base.

If your bench is going to be stationary, go ahead and shim the base level before adding the cabinet. If you want to make a mobile bench, attach the six casters to the underside of the plywood base’s top (Fig. A). Leave just enough room for the casters to rotate freely inside the 2x4 frame. Six casters allow the bench to glide smoothly, even if your floor is uneven. Add the base molding to finish the bench (Photo 13).

Doors, Drawers and Pull-Out Shelves

Start by cutting three door blanks (J). Add the ½-in.-birch edging on all four edges. Put a ⅜-in. round-over all the way around the outside edge of all three blanks. On the tablesaw or router table, cut a ⅜ in. x ⅜-in. rabbet on all four inside edges. Crosscut the drawer fronts (K, L and M) out of one of the blanks and use the other two for doors.

Build and mount the drawers and pullout shelves according to Fig. C.

Now all that’s left is to secure the top to the cabinet (Photo 14). Accommodate the expansion and contraction of the solid-wood top by elongating the two outside holes on the angle-iron cleats under the top (Fig. A). A simple oil finish completes the job. There, now you’ve got all the support you’ll ever need for your woodworking.

Clamp the 12-in. sections together one at a time. You only have one joint to worry about so make it flush. Extra effort here will pay off in the end. You’ll only have to lightly sand for a flat, smooth top.

Mount the face vise, then glue two strips on either side. This will make the front edge of the top flush with the wooden cheek of the vise.

Place the benchtop on the cabinet. This top is heavy, so get a friend to help with the lifting. Check for an even overhang on all four edges. Then secure with lag bolts.

Screw the cabinet onto the base and nail on the base molding. If your bench is going to be mobile, use glue as well as nails to prevent the molding from being inadvertently pried off when the bench is lifted.

Oops!

It’s possible for the edges of the laminated top sections to end up with a slight bow. With 12 in. of width, you’re not likely to straighten them out with clamp pressure. So what should you do?

A jointer is out of the question; the 12-in. section of top is just too big and heavy, even for two people.

We used a simple two-step process with a router and a straightedge to joint our bowed top section.

Cut a straight, shallow rabbet on the bowed edge of the 12-in. top section. Chuck a ½-in. straight cutter with a 1 ½-in. cutting length into your router and set it for maximum depth. Clamp a straightedge to the top section so the router shaves off just enough material to leave a continuous straight edge.

A second pass with a flush-trim bit removes the ledge created by the first pass. Just flip over the top and rout. The result is a clean, straight edge that’s ready for glue-up.

Figure B: Plywood Cutting Diagram

Figure C: Drawers and Pullout Shelves

The plywood drawer bottoms are screwed directly to the drawer boxes. Hardwood edges on the pullout shelves create a lip so tools won’t slide off.

by TOM CASPAR

The Best $250 Workbench

BUILD A MASTER’S BENCH FROM PLAIN OLD 2X4S AND PLYWOOD

Quick, cheap, solid. You can’t ask much more from a workbench, and this one delivers it all. Made of out ordinary construction lumber, this durable, 250-lb. heavyweight has all the features of a master cabinetmaker’s bench: a gigantic face vise, a slick tail vise and a rock-solid base.

You’ll spend a measly $150 at a home center on lumber and hardware. Add $70 to $150 for a face vise. We used a coollooking, top-notch model, but any big vise will do.

Tools and Materials

If you have limited tools, don’t worry. It’s perfectly possible to build this bench using nothing but a pair of sawhorses, a circular saw, hammer, drill, combination drill bit, router and flush-trim bit, hacksaw and socket set. That’s it. A few more power tools (a miter saw, drill press, tablesaw and belt sander) make the job a lot easier, though.

The materials are nothing special, just 2x4s, 2x6s and two sheets of ordinary underlayment plywood (the kind with ⅛-in.-thick face veneer). Be picky when choosing your solid lumber. Look for boards that are straight, free of large knots and have full-width edges. Reserve your straightest boards for the top frame.

Preparing the Plywood

Start by cutting out the plywood panels. Factory edges are good enough, so you don’t have many cuts to make. The few corners that have to be absolutely square are already done!

1. Draw the outlines of all the plywood panels (A1, B1, C1 and C2) on two sheets of plywood (see Fig. C and the Cutting List).

2. Build a temporary cutting guide to fit your circular saw (Photo 1). It’s easy to make by nailing together two overlapping 1x6s cut just over 6 ft. long (you’ll use these boards later in the bench).

Cut panels from construction-grade plywood with a quickie shop-made cutting guide. Even if you’re off by a bit, these cuts are going to be accurate enough to build the bench.

Drill pilot holes through a stack of four panels at once. This is much faster than laying out and drilling one panel at a time.

The edge of the bottom board shows you exactly where the saw will cut, so you don’t have to do any complicated measuring. The top board guides the saw. Nail some extra pieces of 1x6 under the overhang of the top board for balance.

3. Place the cutting guide directly on the lines and cut all the panels.

4. Mark the screw holes (see Fig. D) on one side of an end panel (A1) and a centersection panel (B1).

5. Stack all four end panels on top of each other and drill 5/32-in.-diameter pilot holes all the way through them (Photo 2). Gang up the center-section panels and drill through them, too.

6. Countersink both sides of all the screw holes. (The countersink on the back side removes torn fibers, so you get a tight glue joint.)

7. Paint one side and all four edges of the panels black. This covers up the crazy figure and disguises the screws. A roller works great.

Building the End 2x4 Frame

The method for building each section is basically the same; you glue and screw plywood panels to a 2x4 frame.

1. Cut the top and bottom 2x4s (A2). Measure the length of the legs (A3) directly from the plywood panel (Photo 3). Gang the top and bottom 2x4s at one end of the panel. The remaining distance from the 2x4s to the end of the panel gives you the exact length of the legs. Measure the spacers (A4) by the same method.

2. Cut the legs and spacers. Select the best looking wood for the face of the front legs. Mark “Front” clearly on the good face so you won’t be confused in the heat of assembly!

3. Select one leg for the middle. With a combination square set to ¾ in., draw a centerline down the length of its narrow edge, on both sides. Draw a centerline all the way around the middle of each top and bottom piece (see Fig. D). Line up the centerlines when assembling the frame.

Measure the lengths of 2x4s directly from the plywood panels. The 2x4s should be fairly straight, but you don’t have to machine them any further. All you do is crosscut.

Nail the 2x4s together with a single nail at each joint. The joints don’t have to be super tight or perfectly fitted. The strength of the box doesn’t depend on complicated joinery.

4. Nail the frame together on a flat surface (Photo 4). The floor will do. Make sure all the top edges are as flush as possible, so you have an even surface all around to glue the panels on. One nail at each joint is enough. (The nails only serve to keep the frame together long enough to glue on the panels.) Predrilling the nail holes through the outer members makes alignment much easier.

Assembling the Ends

It’s time to get out the glue and go to town. You’ve got a lot of screws to drive, but there’s no need to feel rushed. Once the panel is positioned the glue will stay wet long enough to run in all the screws.

1. Place one end panel on top of the frame. Nudge the frame square so it lines up with all four edges of the panel.

2. Tack down the panel to the frame with 4d nails at each corner. Turn the assembly over.

3. Run a large bead of glue along all the exposed edges of the 2x4s.

4. Place the other panel on top of the frame, align its edges with the frame and screw it down (Photo 5).

5. Turn the assembly over again, pry off the tacked-down piece of plywood with a hammer and pull out the nails. Then glue and screw the plywood back in place. Scrape off the glue squeeze-out before it hardens.

6. Make the braces (A5) and drill ⅝-in.-diameter holes for the threaded rod (Fig. A). The thick braces spread out the enormous pressure of the nuts over a large surface.

7. Drill holes for the threaded rod through the plywood panels (see Fig. A). Rather than drill all the way through from one side, drill from both sides using the brace as a guide. This ensures that both holes are aligned so the rod will slip right through. Offset the brace ⅝ in. from the panel’s edge (Detail 2).

Screw and glue plywood panels to the 2x4 frame. You won’t need dozens of clamps because the screws do all the work. Painting the plywood black disguises all the ugly screw heads.

Join the knockdown base with humongous threaded rod. Nuts pull the sections so tight that the base is solid as the Rock of Gibraltar. After all, a workbench base can’t be too strong, can it?

8. Cut all the feet (A6 and B4). Bevel the bottom edges to protect them from splintering. Drill deeply countersunk pilot holes for the screws so the screw heads can’t scratch your floor. Screw two feet onto the bottom of each end section.

Oops!

Here’s a goof that’s really no big deal. In the rush to glue the plywood panels on the 2x4 frames, one of the joints opened up. After all, it’s only held together by a single nail. But the strength of the box isn’t compromised at all, because its incredible rigidity comes from gluing plywood to the 2x4s, not the tightness of these joints. No sweat.

Building and Assembling the Center Frame

This frame has two important differences from the end frames you just made. First, it’s got holes for the threaded rod running through the 2x4s that you can’t afford to forget! Second, the frame is slightly shorter than the panels. When you assemble the whole base, any warp or twist in the center frame’s end 2x4s won’t affect the tightness of the joints (see Detail 2).

1. Cut the rails (B2) ¼ in. shorter than the width of the plywood panels. Then cut the stiles (B3).

Rout the plywood top flush with the frame to make a large, even surface for the 1x6 rail. Select your best 2x4 for this front piece. It’s one of the few in the bench that must be perfectly straight. It pays to dig through a large stack of 2x4s to find this gem.

Assemble the front rail one block at a time. Two outer blocks trap one angled jaw of a wooden handscrew: the bench’s tail vise. Each succeeding block is spaced 1-in. apart, exactly the width of a combination square blade. These spaces become mortises for the bench dog.

2. Drill 1-in.-diameter holes in all the stiles. The holes are oversized to allow a threaded rod coupler to pass through (Fig. D).

3. Nail the frame together, then tack a panel to it. Check your alignment. The frame’s top and bottom edges are flush to the panel, but the ends of the frame are inset by ⅛ in. on both sides. Glue both panels, one at a time, as you did with the end sections. Attach the feet.

Assembling the Base

Two lengths of threaded rod (B5) bind the three base sections together with tremendous pressure. This large-diameter rod is surprisingly inexpensive, easy to disassemble and can’t possibly come loose.

1. Cut the threaded rod with a hacksaw (see Cutting List). File a small bevel on the cut ends to enable the nuts to thread easier. Join two pieces of threaded rod together with a coupler and slide the long rod through the holes in the center section.

2. Stand the center section on a level surface. Slip the end sections over the threaded rod and slide on two washers (Photo 6). Tighten the nuts.

Assembling the Top

Select your straightest 2x4s for this frame so you’ll get a relatively flat top. Put the best of the best in the front.

1.