8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Elliott & Thompson

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

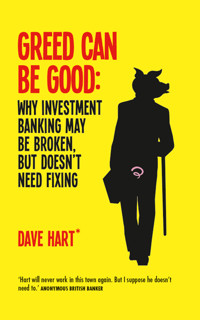

The fallout of the global financial crisis - ongoing recessions, rising government debts, and record levels of unemployment - has lead many to fundamentally question the role the finance industry plays in economies worldwide, with the most stinging criticism levelled at the practices of investment bankers. Lord Hart, former chairman of Erste Frankfurter Grossbank, provides a timely insider's analysis of investment banking in the twenty-first century, offering no easy answers and several revelatory new perspectives on this hotly-debated subject, including: how YOU are responsible for the financial crisis; why bonuses are good for EVERYONE and why bankers will ALWAYS come out on top. Hart's no-holds-barred analysis will be sure to upset and dismay some and infuriate many others - but since when has that ever been a problem?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 67

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

GREED CAN BE GOOD

“Tells it the way nobody should.”

US Treasury official

“Hart will never work in this town again. But I suppose he doesn’t need to.”

Anonymous British banker

“I really don’t think we’re ready for this.”

Association of Investment Bankers

GREED CAN BE GOOD

Why Investment Banking May Be Broken, But Doesn’t Need Fixing

Dave Hart*

Published in association with the

Institute for Financial Understanding

*as told to David Charters

First published 2013 by Elliott and Thompson Limited

27 John Street, London WC1N 2BX

www.eandtbooks.com

ISBN: 978-1-908739-74-2

Text © David Charters 2013

The Author has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and

Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this Work.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Designed and typeset in Minion by MacGuru Ltd

Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

CONTENTS

Foreword

Introduction

What’s it all about: is there any value in what we do?

Human capital: it’s the people, stupid

Conspiracy theories: was there a master plan?

Virtuous spending: why bonuses matter to the economy

Giving back: the next Big Lie

Friends and allies: we did not do it all ourselves

Bankers, lawyers, accountants: are we equally bad?

The future: it’s the market, stupid

Banking and the environment: do we care?

Do clients matter?

The new City: an ocean of diversity

So what is our legacy?

The London effect

Where do we go next?

Postscript

Index

FOREWORD

.

Privilege should always carry responsibility. As a senior investment banker I have been fortunate in leading an extraordinarily privileged life, the culmination of which was my elevation to the Lords. I hope you will forgive me if I sound just a little pleased with the way things have gone. At least for me.

There are quite a few of us bankers here – perhaps more than you might think, and sitting on all sides of the chamber because we like to spread ourselves around. The upper house of the British Parliament serves as a repository of all kinds of expertise, which is made available for the benefit of the nation.

You can find anyone here, from a convicted felon at one end of the scale, to a retired senior banker such as myself at the other. Or perhaps it is the other way around. So when the chancellor suggested that I really ought to share my views – I think he said ‘Come clean’ – on the credit crunch and in particular on the role played by investment banks, I answered the call to action and did what any self-respecting former banker would do when faced with a similar task.

I took myself off to the Caribbean with Gisela, 24, from Brazil, and Tatiana, 23, from the Ukraine – my personal assistants for the duration of my stay – and slaved away furiously for anything up to an hour a day on the text that you now have before you.

The Institute for Financial Understanding supported me in my endeavours, and various senior colleagues from the investment banking industry joined me for some or all of my time there, sharing freely of their insights and expertise, and bringing their own personal assistants, who were happy to rotate between us and lend a hand, a shoulder or indeed whatever was most appropriate at the time.

It was an exhausting trip. We were relentless in grinding through all that lay before us, nailing everything in the no-holds-barred approach at which investment bankers excel. The result is a simple essay that seeks to shine a light into an area so often misunderstood and misrepresented: the City of London and the global investment banking industry.

It goes without saying that the opinions expressed here are my own, and that I take full responsibility for any errors and omissions. Perhaps the only time an investment banker ever took responsibility for anything – so far anyway.

Lord Hart of Hartless Common,

House of Lords,

London,

January 2013

INTRODUCTION

.

Is that it? The credit crunch not exactly over, but at least sufficiently boring and familiar that we’ve all just moved on, with our ever-shorter attention spans, to the Next Big Thing?

Quite possibly. And yet we should not allow ourselves to forget the lessons of the most expensive financial crash in modern history. The music nearly stopped for good. It cost the global economy trillions. It is no exaggeration to say that it changed the world. Generations to come will still be paying off the debts that it created, and millions of people have already paid the price – in unemployment, social dislocation, busted banks and businesses, shrinking economic opportunities and all the ills of a world unnecessarily impoverished and which must now pick itself up, dust itself down and, above all, not forget what happened and why.

As an investment banker – and a very senior one – I was part of the privileged elite that brought this about. We benefited enormously from decades of artificially inflated prices, a bonus-driven culture based on ‘me now, and I want it all’, and torrents of cheap money that we thought would last forever. We thought we knew best. We had to be smart. Look how much we were taking home. You don’t earn that kind of money for being average, do you?

Not only that – we actually created money. We hired bright young things with PhDs in subjects that no one really understands, let them loose with computer programmes and enough computing firepower to win a war. And yes, we let them loose to swing your money around, because they were winners. Except they lost. Massive miscalculations that should have been picked up by checks and balances in the system, by older, wiser heads, even by regulators and government – please, don’t laugh – were not only missed but wilfully ignored, until the computer-gaming generation of geeks let loose on trading floors learnt that when things go wrong in the real world you can’t press Restart, and all those extra zeroes on the end do matter after all.

We had a hell of a party, and the rest of the world had our hangover.

The bank of which I had the privilege to be chairman, Erste Frankfurter Grossbank, was at one time the largest bank in the world. I joined it from Bartons, one of the UK’s oldest, most traditional names. In the game of life, I was a winner.

I was paid millions of pounds a year, even in bad years when things went wrong. When they went well – generally because of market conditions rather than anything we did – I was paid tens of millions. But did it make me happy?

Of course it did. I loved every minute of it. Money isn’t guaranteed to buy you happiness, but it sure helps. I’d be a hypocrite if I said I didn’t enjoy the lifestyle: the fine wine, the expensive, easy women, the drugs, the accumulation of material possessions – property, art, fast cars, the travel in helicopters and private jets (we called them ‘smokers’) to exclusive resorts where the great unwashed who eventually bailed us out didn’t even get to press their noses against the glass. Still don’t, in fact. If it is true, as someone once said, that politics is show business for ugly people, then high finance is show business for rich ones. Either way, we got the pussy. And I loved it all.