10,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Elliott & Thompson

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

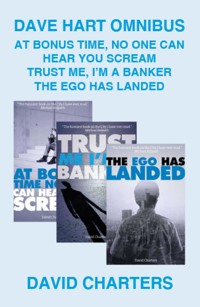

Three novels featuring the anti-heroic banker, Dave Hart, the satirical creation of David Charters. This omnibus edition contains the novels 'At Bonus Time, No One Can Hear You Scream', 'Trust Me I'm a Banker' and 'The Ego Has Landed'.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 716

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

Dave Hart Omnibus: At Bonus Time No One Can Hear You Scream, Trust Me, I’m a Banker and The Ego Has Landed

DAVID CHARTERS

Omnibus Edition first published 2012 by Elliott & Thompson Limited

27 John Street, London WC1N 2BX

www.eandtbooks.com

ISBN: 978-1-9087-39551

‘At Bonus Time, No One Can Hear You Scream’

ISBN: 978-1-9040-27744

Copyright © David Charters 2004

First published in 2004

The right of the authors to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

***

‘Trust Me, I’m a Banker’

ISBN: 978-1-9040-27751

Copyright © David Charters 2007

First published in 2007

The right of the authors to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

***

‘The Ego Has Landed’

ISBN: 978-1-9040-27768

Copyright © David Charters 2007

First published in 2007

The right of the authors to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Contents

At Bonus Time No One Can Hear You Scream

Author’s Note & Acknowledgements

Text

Trust Me, I’m a Banker

Dedication

Author’s Note & Acknowledgements

Text

The Ego Has Landed

Dedication

Author’s Note & Acknowledgements

Text

AT BONUS TIME NO ONE CAN HEAR YOU SCREAM

AT BONUS TIME NO ONE CAN HEAR YOU SCREAM

DAVID CHARTERS

Author’s Note & Acknowledgements

BONUS TIME started life as a short story, but never knew when to stop growing. My publishers encouraged me to give it full rein and you have before you the result. It is not so much a chronicle of a particular time in the City of London, as the exploration of a type of character and the way that character responds to the extraordinary pressures placed upon people in the extreme situations that the City produces. Among my former colleagues, even the most ruthlessly aggressive fall short of Dave Hart and his fellows. Bartons, their bank, is not modelled on any single British merchant bank, but rather draws together the worst features of the scramble to emulate the Americans, borrowing the ugliest aspects of the soulless finance factories of Wall Street, while missing the lessons that the best US investment banks could have offered to help ensure an independent future for more British firms.

I am grateful as ever to a number of people for their help and input: Lorne Forsyth, John McLaren and Nick Webb deserve special mention, as well as Gavin Henderson of Laidlaw Capital, and my oldest son, Mark.

LAST NIGHT I killed my boss. It was the second time this week, only this time it was much worse. He was sitting at his desk in his big, glass-sided, corner office, looking out at the trading floor with its hundreds of identical workstations, the computer screens, the phones, and us, the worker bees who feed the machine. Looking at us, as we stayed late in the run-up to the annual bonus round, putting in face time to look good, keeping busy, trying to persuade him how essential we all were. Well, I’d had enough. I wasn’t essential anymore – at least I didn’t feel as if I was – and I was going to act before someone took the decision for me.

I COUGH nervously, glance around at my colleagues who all have their eyes glued to the screens in front of them, and pick up my briefcase from under my desk, leaving my jacket over the back of my chair. Now, this may sound straightforward, but you don’t normally carry your briefcase around the trading floor unless you’re going home, and when you go home, you put your jacket on. But if I put my jacket on first – at this time of year – the rest of the team will look at me and I don’t want to attract attention, not at this stage.

So I leave my jacket but pick up my briefcase and walk in a lopsided way, half hiding it in front of me as I make my way to his office with my back to the team.

I step inside the open door and close it behind me. I reach across and pull the blinds, so we can’t be seen from the floor. He looks up, puzzled.

‘What are you doing?’

I smile, reassuring, ingratiating.

‘Rory, there’s… something I wanted to discuss with you.’

He sighs and looks at his watch. ‘Okay, I’ll give you five minutes, but do me a favour – no more special pleading about the bonus, okay?’

‘No, no more special pleading, Rory.’ I smile again, a little nervously – still in character – and open my briefcase on his desk, but with the lid facing him so he can’t see what I’m taking out. ‘In fact no pleading at all.’

I close the lid with a firm click and swing a sixteen-inch machete up in the air.

Now, before you say anything, a sixteen-inch machete may not seem much, but it had to fit into my briefcase, which is not large. Even in London you can’t just go and buy a full-sized machete without attracting some degree of attention. As I like to think I’m a little smarter than some mere criminal on the street, I’d bought the machete at auction, at Christie’s, along with a collection of other memorabilia of famous nineteenth century explorers in Africa. So when I swing it through a broad arc and bring it down with a thunk into the middle of Rory’s perfectly coiffed, fair-haired, blue-eyed skull, I’m actually using a piece of history.

The problem is, it gets stuck. The weapon goes thunk, right into his head, splintering the bone. My arm is driven by the strength that can only come from years of resentment, humiliation, nervous anxiety, pitiful gratitude and festering anger. He keels over, gently and silently, his eyes roll upwards and he bumps his head on his desk with a sigh. Seeing him lying there, helpless, I put one hand on his head and struggle to wrench the machete free for a second go (and to be honest, for a third and a fourth – I’d worked for Rory a long time).

And then he gets up! No kidding, he actually shakes his head, causing me to leap backwards, my eyes wide with fear and disbelief. He pulls himself together, lifts himself up from the desk, blood streaming down his face, eyes wide open, with the machete still sticking out of his skull. He comes round the desk towards me.

‘You always were a loser.’ His words have an icy venom to them – which I suppose is understandable. ‘A loser, a no hoper, a truly second rate, sub-standard investment banker. The clients don’t even like you, let alone respect you, half of them only deal with you out of sympathy, and you have no future here or at any other firm.’ He jabs his finger in my chest to emphasise the points, and as he finishes, he reaches up, taking hold of the machete, grasping the handle, and pulls it out of his head, allowing a stream of blood to come gushing out of the crack in his skull splashing down over his face onto the carpet. ‘You can’t do a damned thing right.’ There’s blood all over the machete as he hands it back to me, and more blood runs down his forehead and face, but it doesn’t seem to bother him. ‘Now get out of my office. I have work to do – including some key bonus re-calculations.’ As he says this, he gives me a long, meaningful stare – one of the ones I always hate, because when someone looks at you like that, you just know they’ve found you out – and then he flicks a drop of blood off the end of his nose and goes back to his desk.

When I get back to my workstation, my shirt is sticking to my sides with sweat. I pull my handkerchief out and mop my brow. As I glance around, I catch the eye of some of the other team members.

‘Brown-nosing again?’

‘Looks like it didn’t pay off.’

‘Rory’s got the measure of you.’

And I start screaming. I scream so loud that I wake my wife.

‘Darling – darling, are you all right?’

I shake my head to clear it, and reach for a glass of water from the bedside table. Wendy turns the light on.

‘It was one of those awful dreams again, wasn’t it?’

I nod, too shaken to speak.

‘Oh, my darling,’ she smiles, trying to be reassuring, and hugs me, though she clearly doesn’t appreciate the sweat covering me from head to toe. ‘Come on, darling – look on the bright side. It’s not long now, is it? Then all this uncertainty will be over. It’s… how many days?’

I glance at the clock on the bedside cabinet. Twelve thirty – half-an-hour after midnight, another day has started. ‘Fifty-two days,’ I gasp. ‘Fifty-two days until we know.’

Monday, 25th October

B minus 52

IT WAS 6:30 in the morning. I was sitting on the tube, on the Circle Line to Monument, staring into space, working out what I’d do with a million pounds. Now, before you say anything, let me explain – even senior investment bankers take the tube sometimes. I know that Rory with his chauffeur-driven car would never be seen dead on the People’s Underground, and why should he? He’s the boss, after all. But for the rest of us, at least those who live in Chelsea, the journey into the City is quickest by Underground, especially first thing in the morning, even if it is a little democratic when it comes to things like getting a seat and who you rub shoulders with. And I know, I know – you don’t need to say it. It’s true that the man sitting next to me doesn’t smell of Armani Mania.

He smells of… well, let’s just say he smells. And a lot of these people haven’t even made their first million, and many of them never will. That’s capitalism. It’s enough for me that I know. I don’t need to say anything.

But back to that million. We all know a million isn’t what it used to be. To begin with, the Chancellor takes forty per cent. So a million is already six hundred thousand. Then the bank won’t pay it all in cash. Probably half the balance will be in some form of share-based incentive – options, deferred shares, some weird derivative, or whatever. But it won’t be cash and you can’t spend it now – it only turns into folding money slowly, over a period of years, perhaps three or even five years, providing you stay at the bank and don’t move to a competitor. If you do that, you lose it all. That’s why they call these things golden handcuffs. So your actual cash in hand is perhaps three hundred thousand, and these days three hundred really doesn’t go far.

Take an example. Have you any idea how much a Porsche costs? I thought not. Well the basic Boxster comes in at a mere £30k, but no one, I mean no one, serious can drive one of those in the Square Mile. The minimum is the 911 Turbo Cabriolet and for that you’re talking the thick end of £100k. So already a big chunk of my bonus is gone.

I know what you’re thinking – why buy a 911 at all? We already have a Range Rover Vogue of course, with the usual extras – so why buy a second car? Well the thing is, we have to have the Range Rover. Wendy needs it to do the school run from our flat in Sloane Square to Cameron House, the private nursery school which Samantha attends, at the other end of the King’s Road. It’s almost half a mile, and kids these days need protection, and so does Wendy – not the world’s greatest driver – so a big 4 X 4 is essential driving in Chelsea. It’s also good for giving the impression that we have a place in the country, which we definitely don’t yet, but would do if Rory ever got off his arse and gave me a decent bonus. And of course whenever Wendy ventures outside Chelsea, she needs protection even more – like when she takes Samantha to her Little Sweethearts ballet class in Fulham, or to her Young Prodigies violin lesson in Pimlico, her Gymnastics for Toddlers sessions in Battersea, or her Little Tadpoles swimming class in Putney. Don’t laugh – if you don’t do this stuff for your kids, they might not become a rock star, or Prime Minister, or win the Nobel Prize. Even White Van Man pulls over when he sees Wendy weaving down the middle of the road, talking on her mobile, staring into shop windows, at the wheel of a Range Rover.

But back to my car. We ought to be a two car family, because if I ever need to drive to the office, for example on a Sunday, I can’t arrive in a Range Rover – at least not a clean one, the way they tend to be in Chelsea. At weekends Rory drives a DB7, but then he would, wouldn’t he?

So once I’ve finally got myself a decent car of my own – a 911 Turbo Cabriolet – what else do I need? We still owe a hundred thousand on the mortgage on the flat, which we’ve paid down steadily over the past few years, and it would be satisfying to own it outright, but we already tell people we own it ourselves, so there ought to be something more… demonstrable that flows from this year’s bonus. We could think about a place in the country, but then people would expect to come and stay, and we simply don’t have the kind of money you need to buy a place like Rory’s: two hundred and fifty acres in Sussex, his own shoot, nine bedrooms, two guest cottages, five staff – you know the sort of thing. Or maybe you don’t. Anyway, a cottage is definitely out of the question, even though in terms of strict space requirements, Wendy and I, and Samantha (who’s three) could technically survive in a cottage – after all, we only have three bedrooms in Sloane Square. But it doesn’t matter, because a million doesn’t do it, so there’s no point discussing it further.

Watches – and jewellery – always used to be a sure-fire sign of a successful bonus round, though these days people are getting more cynical. If Wendy and I treat ourselves to a new Rolex each, or better yet the latest Patek Philippe, people might think I really haven’t done well and it’s all a bluff.

We could re-decorate the flat. I haven’t costed that, but one of those chi-chi interior designers could transform the place for us. The problem is, I sort of like it the way it is, and I’d hate the disruption of having to move out while a bunch of Polish builders and Croatian decorators moved in. And it always costs more and takes longer than they say – we pay Chelsea prices and get Warsaw delivery times.

If I only get a million, a few key purchases around the home are probably the best compromise – an antique dining table with chairs (less than £30k?), a new centrepiece picture for the drawing room (£20 to 25k?), a new set of crockery (£3 to 4K?) and perhaps new curtains (£10k?). We’d still have change for Barbados at Christmas, not forgetting the Porsche, and the balance I’d use to pay off the overdraft.

Overdraft? I can see the question in the thought bubble over your head. Well, yes, I do have an overdraft. I know what you’re thinking. Why does a successful investment banker have an overdraft? Well, actually we all do.

NO ONE LIVES on their salary any more. Besides, Rory only pays me £100k a year, and Wendy couldn’t begin to live on that. So what do you expect?

At 11:30 I had a meeting with the Finance Director of Pattison Construction. PC – as we call them on the team – is one of the biggest and fastest growing construction companies in the UK, having come from nowhere over the past five years. We took them public on the stockmarket two years ago, and now they’ve come to us for advice on what to do next. Yes, really – they’ve come to us for advice.

It amazes me, but people still do that. Naturally, my advice is that they should do whatever will pay the bank the largest fees. In this case, I recommend we list their shares on the New York Stock Exchange, so that they can access US investors, increase liquidity in their shares and send their stock price higher. None of this is true, of course. The most serious US investors already can buy their shares, without the expense and trouble of a US listing. Creating a separate pool of shares in the US reduces liquidity, and in times of uncertainty, US investors would dump their shares pretty quickly and send the stock lower. But that’s all detail. I like to think I’m a big picture man. The big picture I’m thinking of today is my bonus, because as you know, it’s that time of year.

On reflection, any time of year is that time of year, but the last few weeks running up to bonus particularly so.

Anyway, PC nods, makes all the right noises and I orchestrate the presentation like a circus ringmaster. We explain why US investors have a different valuation approach to the construction sector and will push his stock higher, a representative of our US operation explains why our tiny New York office is best equipped to do the job (after all, why would anyone want to hire a US firm to do a job in the US?), and finally I wind up with my assurance of the firm’s total commitment, how much we want the business, how great it will be for them, the strategic vision, the next step forward – sometimes I think I could do this stuff in my sleep. It’s not that investment banking is undemanding work, it’s just that at times it’s repetitive. Like repeating the same script a hundred times. Or a thousand. I’ve been doing this a while now. In theory you get slicker, more persuasive, more reassuring, but it can come to sound… jaded. Not that I’d ever get bored with my job, of course. I’m committed, not quite in the way that lunatics get committed to an asylum, but committed nonetheless.

Afterwards, he tells me how impressed he is with our presentation, how highly he values our input, and how useful it is to be able to get genuinely sincere, impartial advice. For a moment I look at him and wonder if he’s taking the piss, but then I realise he means it.

Christ, I’m good.

WENDY AND I went to a dinner party at the Finkelsteins’. He runs the swaps desk at Hardman Stoney, one of the most successful US investment banks. He never has anything to say, always arrives at least half-an-hour late to his own dinner parties, and always looks distracted – almost vacant, though obviously that can’t be right, because he runs the swaps desk at Hardman Stoney.

The Finkelsteins have an amazing apartment in Holland Park – the sort that Wendy dreams of. You come in through a grand reception area with marble floors and twenty-four hour porterage, step into a big mirror and marble elevator, and get out onto a large landing that serves just two apartments. You buzz at double doors, both of which open when your host’s butler (hired for the night – don’t worry, this isn’t Rory’s place) receives you and takes your coats.

The drawing room is huge, with a great view and interesting art: a contemporary bronze here, a classical marble bust there – you know the sort of thing. Or maybe not. Anyway, there are a few coffee tables and some couches, but mostly the impression is space and order. And a ‘to die for’ black babe dressed as a waitress offers you a drink with a ‘come to bed and fuck me’ smile on her face and a knowing look in her eyes. Where do they find these girls? Why can Wendy only find short, fat Filipinas and Essex girls who claim to know what they’re doing, but only spill things on guests, or worse yet, on the furniture?

GLORIA FINKELSTEIN is dressed from head to toe in Chanel – and it’s wasted. Twenty thousand dollars, and you still can’t defeat nature. That’s without the hair stylist, the manicure, the pedicure, the botox, the lyposuction, the personal trainer, the masseur and the expensive suntan. I guess she must do something for Matt Finkelstein (or at least she did once upon a time). A few good memories and a killer of a pre-nuptial can do a hell of a lot for these American investment bankers’ marriages.

Wendy on the other hand is wearing Donna Karan – a simple pale blue number to match her eyes that cost us a mere three thousand dollars on our last trip to New York. In Wendy’s case it’s the jewellery that does it – twenty thousand pounds’ worth of ‘heirlooms’ for Samantha around her neck and wrists (that was how she justified them), mostly from Theo Fennel, with earrings from Elizabeth Gage: stunning, so much so that Gloria Finkelstein pays her the ultimate tribute of ignoring them, and compliments her instead on her new handbag (a mere three hundred pounds from Coach).

I take a glass of champagne from the black sex machine, ignoring Wendy’s ‘evil eye’ and wonder what she would say if I offered her a thousand pounds to go to bed with me. I take a sip and discover – to my utter horror – that it’s Krug. Not only that, but just in case I didn’t notice, the bottle is sitting in an ice bucket on the sideboard, propped up so the label is on show. If that isn’t typically crude one up-manship, I don’t know what is. I make a mental note – next time Matt Finkelstein drops by, I must open a bottle of vintage Cristal. (Second mental note: order some).

We exchange the usual pleasantries: air kisses, compliments, how wonderful, it’s been so long, you look amazing, how are the children, before we get down to the real business of the evening (and this even before Matt Finkelstein has appeared!) – how are you doing? Sounds like a simple question, doesn’t it? Except it doesn’t really mean what it says. What it really means is (and at this point Wendy looks nervously in my direction, relenting on her previous irritation at my preoccupation with the black sex bomb): are you going to be paid more than my husband this year, and if so, what does it do to our relative positioning in the social pecking order?

Great, isn’t it? As if it wasn’t enough that the husbands compete, the wives have to do it too. My husband earns more than yours, he can buy me a bigger house/car/boat/holiday home and afford a better personal trainer/masseur/beautician/guru/tennis coach and we can spend even more money than you on exotic holidays/dinners at fancy restaurants/tickets to the boring fucking opera/weekend breaks in stately fucking homes and WE MUST BE FUCKING HAPPIER THAN YOU FUCKING LOSERS. Or something like that. And anyway, since we all do this stuff, it must be right.

Wendy does her best ‘confident corporate wife’, glancing at me, looking quietly confident, silently gratified at some hidden knowledge that she and I alone can share – I’ve been told something. Rory must have given me a hint. Obviously I can’t say anything: everyone understands that. Especially Gloria. Wendy puts on such a good performance that we don’t actually need to say anything. Gloria looks taken aback, perturbed, ever so slightly unsettled in a quite delicious way, and leaves us with unseemly haste when the bell rings to announce the next guests.

To my relief, it’s the light entertainment. Gloria Finkelstein, ever the thoughtful hostess, has organised a Real Loser. He’s here so we can all unite against him and reinforce our sense of security and permanence.

Joe Smith ran forward Foreign Exchange trading at SFP – Société Financière de Paris – until June last year. Then they closed down and pulled out of the London market. Not his fault, of course, his team was profitable, but that makes no difference: when he looks at me, and I look at him, we both know. Not that I’d ever say anything, of course. That’s part of the fun.

Our wives know too. His wife, strangely known as Charly, is Hong Kong Chinese, and I’ve always had a soft spot for her – I bet she’s a real goer. She’s wearing a brightly coloured, vaguely oriental style, silk mini dress of indeterminate origin – oh dear, my dear, no label – with pearls – okay, I guess – and intricately patterned gold earrings that probably come from the Middle East –I bet they don’t have hallmarks. She’s in great shape, but that really isn’t the point. I wonder what she would say if I offered her, oh, let’s say ten grand – or maybe fifty, he’s been unemployed for nearly a year now…

‘Joe, how are you? And Charly, how wonderful to see you!’

Wendy and Gloria rush to embrace the arriving guests, revelling in their superiority. Sweetness and success: moments like this are what it’s all about. But it’s all relative – imagine what it feels like for a woman to be married to Rory.

Joe is embarrassed, trying not to be defensive, he has lots of possibilities, he’s still exploring his options, obviously the market doesn’t help – and yes, we all nod and no one engages with him: because we don’t have to, do we? He’s a loser.

Before you say anything, I know it’s not his fault – he ran a profitable, successful team, he made a lot of money for his firm, had a fearsome reputation in the market, and paid his people well, at least as long as they performed. It’s not that he was kind, you understand. After all, kind is for girls. He was ambitious, aggressive, and like most of us, he knew how to smile upwards on the greasy career ladder and shit downwards. But he didn’t have friends. Not that any of us do, really. But he made it particularly clear that he didn’t care what his peers at other firms thought, and that was a mistake.

Most of us at least go through the motions, staying part of the ‘club’, because you never know when you might need a helping hand. Of course, for all I know, Joe’s a loving, loyal husband and a wonderful father to his kids and helps small, furry woodland creatures in his spare time. But he’s still a loser, and we know it and he knows it and Charly knows it too. He committed the Cardinal Sin: when he found himself in the wrong place at the wrong time, he had no friends and no Plan B. He was naked and alone with no one to cry to, and when that happens, the City is a barren place – the sort of place that makes people become unravelled.

Just as the conversation is stretching out deliciously, reinforcing my sense of confidence and good fortune, Matt Finkelstein arrives and pops the bubble.

‘Hi, I’m sorry, so sorry – we’ve just priced the biggest reverse forward equity swap with collars, caps and inverse reference prices that’s ever been undertaken outside of the US.’

We all stare at him. Matt Finkelstein has zits. I know I shouldn’t raise this now, just ahead of dinner, but if you were here you’d see them anyway. He’s tall, skinny and is losing his hair. He would say he’s lean, and it’s true he does work out, in the special gym set aside for the use of Managing Directors only at Hardman Stoney. He would probably also say he’s clever, and in a manner of speaking, that’s true – though only in a narrow, specific way that wouldn’t really help him; for instance if civilisation came to an end as the result of a nuclear holocaust and he had to fend for himself in the wild. Sure, he goes to the opera, but if you were to ask him who wrote Tosca, he’d gaze vacantly at you, say ‘Huh?’ and look around for some Eurotrash they’d hired on their graduate trainee programme to answer the question.

‘Wow, Matt – fantastic! Congratulations. You must be over the moon.’ I don’t ask how profitable the trade was, because they don’t necessarily know – these swaps guys are so smart, they bullshit their bosses every time they do a deal, book some huge notional profit for bonus purposes, and let their successors unwind the mess in a few years’ time when it matures.

But the really clever thing about Matt’s trade is that he’s done it now. A dollar earned in the run-up to bonus is worth ten dollars earned at the beginning of the year. My last major success was back in March, which gives me a slightly sick feeling. I take a sip of Krug, but that only makes me feel worse.

‘Why don’t we go straight through and sit down?’ Matt steers us through to the dining room, and can’t help grinning as he sees the looks on our faces.

Their dining room has been transformed. They have a new centrepiece picture hanging over the fireplace – some contemporary splurge of colour that I’m sure we’re all meant to recognise and must have cost a fortune, as well as a new dining suite, at least new to them. It looks Georgian to me – with crockery that I’m sure is also new from the last time we were here. But the real killer is hanging on the wall to my right: it’s roughly six-feet by five, very glossy and dark. It’s a photograph, by Hiroshi Sugimoto, of a seascape by night. To you and me, it’s a six-foot by five-foot dark patch on the wall, but to those who know, it says that this man, Matt Finkelstein, has two hundred thousand dollars to spend on a museum piece of modern photographic art. Since it is completely black, I wonder for a moment if Matt could have sat in a dark cupboard with a camera with the flash disconnected and taken it himself, then got it blown up, but I don’t think he has the nerve. If you study these things close up, you can see the wave patterns and starlight in the darkness. Obviously I can’t acknowledge its existence by studying it, but he can’t take the chance that someone won’t. So it must be the real thing.

Damn him! He’s got his retaliation in first: he’s done all this stuff before the bonus. How could he? I’m sure he doesn’t make that much more than I do, and Gloria is High Maintenance in a way that makes Wendy look modest. The only thing I can think of is debt – he must have mortgaged himself up to the eyeballs, and he’s counting on the bonus as his lifeline. I smile and find myself reluctantly compelled to pay him the same compliment that Gloria paid to Wendy when she saw her jewellery: I ignore everything and sit down, pretending not to notice.

Wednesday, 27th October

B minus 50

TODAY I SAW a dead rat on the pavement. Now, if you’re tempted to say, ‘So what?’, let me make clear that this is quite unusual for Sloane Square. I’m sure there are rats all over London, in fact there are probably as many rats as people, living off the rubbish that piles up on the pavements, surviving in the sewers and the gutters and rarely seeing the light of day. But this one had chosen to come out of the sewers and die, here on the pavement outside my flat, for me to find just as I’m leaving to go to work.

In case you’re wondering, I’m not superstitious, but it did put me in a really negative frame of mind. I wondered if it could somehow be a metaphor for my life, and that made me think about God. Not the Money God, you understand, but the other one – the one I don’t really believe in except for social occasions like weddings and christenings. If there were a Real One – just speaking hypothetically, of course – and He were looking down on this ant-heap of a City, scrutinising us, what would He make of us? Would He think we were actually doing any good with our one unrepeatable lives, making a difference to our fellow man, or would He view us simply as parasites, an irrelevance that could be wiped out with a giant aerosol spray, leaving the planet a cleaner and happier place?

You can guess where I came out, as I sat on the Underground and tried to focus on my newspaper. I found myself wondering if there was anything I’d ever done that was worthwhile, not in the sense of generating fees for the firm, but in the sense of making the world a better place. Like Bob Geldof. He was a rock star, and by and large I think rock stars are pretty worthless people – though it has to be said that the big names do make real money. But Geldof was different. He tried to make a difference, not just to his own immediate circle, but to the whole world. Would I ever do that, spinning madly like a hamster in a wheel on this crazy money-go-round? And if not, should I be worried about it? Would I one day look back and say it was all worthless?

Well, not if I made two million this year. Two million would still not be real money, but it could make a difference. With two million – which after tax and assuming half the balance is held back in deferred shares or options is really only six hundred thousand – I could buy a proper place in the country – obviously with a second mortgage, because six hundred by itself doesn’t get you there, but who cares about debt? Sensible leverage is, well… sensible. With two million, I could buy the kind of place where Wendy and I could invite houseguests for the weekend, possibly with our own shoot, and still get the 911 and the extras I was thinking about for the flat. Though on reflection the extras for the flat have less appeal now that Matt Finkelstein’s beaten me to it.

By the time I reached Monument station I was feeling a lot better – forget rats, think bonus.

Thursday, 28th October

B minus 49

TODAY RORY was happy. The sun shone and we were all smiling as we sat at our workstations and contemplated our good fortune. Truly, we work for the best of all possible bosses at the best of all possible firms.

Just kidding.

Rory called a departmental meeting. We were all a little nervous as we filed in to the large conference room at the end of the trading floor. We didn’t show it, of course – except by the fact of all the joking and light-hearted banter going back and forth. Anyone observing us would have thought we were on something.

When Rory cleared his throat, you could have heard a pin drop. I was staring at the conference table, wondering what the hell was going on. You see, this was not our regular weekly bullshit session, where we take it in turns to try to claim credit for anything that’s gone well, distance ourselves from anything loss-making and position ourselves as busy, productive, irreplaceable members of the team. This was a special meeting, called in the middle of the trading day, at theoretically one of our busiest, most productive times, and at this time of year you only do that for one reason: the bonus. I could feel sweat underneath my shirt and wondered if I should have put my jacket on, but that would have been too conspicuous. Anyway, I could see others were sweating too.

‘Thank you all for coming.’ I could have punched his ugly mug. As if we had a choice. At this time of year, if your boss asks you to stand on your head and sing Yankee Doodle, you ask in what key. ‘I have some important news concerning compensation.’

That got our attention. I felt as if I could hear the entire room breathing – all thirty of us. The beating of my heart, my own pulse sounding in my ears, someone’s stomach rumbling a few places down the table – everything became surreal for an awful, agonising moment. Let it be good news, dear God, please. Of course it wasn’t good news – it couldn’t be. It was all part of the softening up process.

Rory waved some papers, which none of the rest of us could see. For all I knew they were blank, just a theatrical prop to help get the message across. ‘The department…’ He paused, looking around the room. ‘The department is thirty per cent behind budget.’ A further dramatic pause. ‘That can mean only one thing.’

One thing? It could mean several. It could mean Rory had failed to deliver what he promised management, and had decided to do the honourable thing – fall on his sword and resign. His share of the bonus pool would then be divided among his subordinates, whom he so outrageously misled with his misguided strategy, and for which he insisted on taking sole responsibility. No – this is investment banking, after all. It could mean he wanted a presentation prepared, to which we could all contribute, on a fully democratic basis, to explain to management that the budget was never realistic, but merely a ploy to get him paid more last year, and that it should therefore be revised down to a more achievable level. No – he’d never admit to mere human fallibility. Most likely, it meant we were going to tighten our belts, fire some juniors, and have our expectations managed downwards.

‘This means we are going to have to tighten our belts.’ Bingo! ‘We need to get control of our costs. With immediate effect, First Class travel will be restricted to members of the Executive Management Committee only.’ Around this particular table, that means him. ‘Travel to the airport will no longer be by taxi or limousine, but by public transport, excepting those employees whose terms of employment specify their means of transport.’ Him again – a chauffeur’s included in his contract. ‘Overnight subsistence rates will be cut, and the list of approved hotels reviewed for those employees who do not have line responsibility for costs. In other words, if you’re not liable to carry the can directly with management for costs incurred, you will be obliged to make economies.’ He’s the only one with that responsibility in this room, so I suppose he can work out for himself which hotels he’ll stay in and whether he really needs the Presidential Suite. ‘This is going to be tough on us all.’ No, it’s not. You’re exempt. It’ll be tough on the rest of us. ‘But we have to keep our costs under rigorous control. I will also be reviewing the staffing requirements of our various business activities in terms of junior support.’ True leadership – be decisive, fire some juniors, just before the bonus. ‘And it goes without saying that compensation prospects for all of us are less rosy than they would have been had we actually delivered on what we all signed up to.’ Now steady on – none of us came up with that budget. That was yours. We just get to pick up the tab.

We all nodded our heads in agreement. Then came a flash of inspiration.

‘Rory, we’re with you on this all the way.’ I could see heads turning in my direction, envious scowls distorting their features. ‘Not only will we focus on costs – we’ll focus on revenues too! We need to really go for it this side of Christmas, show management that we can deliver and that we really are the best team in the City of London!’

I can see I’ve pissed off everyone in the room, except Rory, who’s nodding sceptically in my direction, but then beams at us all and agrees vigorously, causing others to do the same. Soon the whole room is full of nodding, smiling, happy faces, as we all agree with the wisdom and intelligence of our Beloved Leader.

DID I TELL you Rory has five homes? Yes, just the five. He has a five-storey house in Belgravia, with four staff, not counting his chauffeur, who’s paid for by the bank. Then he has his ‘place in the country’, in Sussex, which I’ve already told you about. He has a chalet in Verbier, which as far as I can tell he never visits, and only has two staff; a villa near Antibes (four staff – he tries to spend most summers there, leaving early on a Friday afternoon and coming back on Monday mornings when he can’t actually take a whole week off), and finally an apartment in New York (two staff), overlooking Central Park, in preference to the suite at the Four Seasons that he always used to take when he went on business. Someone said the firm might even be paying for his place in New York as part of his contract. Anyway, that makes five homes and seventeen staff, not counting the driver. He’s a one-man employment machine, providing jobs and opportunities for so many people, his contribution to third-world development alone must make him a dead cert for a place in heaven.

By my calculations – based only on rumour and speculation – Rory must have been paid over twenty million pounds since he joined the firm four years ago. But do you think it makes him happy, all that material wealth? You bet it does. It makes him as happy as a pig in shit.

Wouldn’t it make you happy?

Monday, 1st November

B minus 45

THINGS ARE HOTTING UP. I was sitting in my usual cubicle in the gents, reading a copy of The Sun left there by one of the traders, when I overheard a whispered conversation between two colleagues.

First voice (sounds American, I’m not sure who it is): ‘Jackie’s suing!’

This must be Jackie Thornton, a Vice President who was once considered a rising star, but seems to have had a bad year.

Second voice (Bill Mackay, who sits at the next but one workstation to me): ‘Is that right? But do you think it’s true?’

‘Nah – but right now she’s desperate. All she has to do is threaten to sue and she becomes ironclad. Not only can she not be fired – assuming anyone other than juniors will get fired – but she has to be well paid.’

‘But the guy she’s accusing is gay – she must know, surely? Everyone else does. He’s the last person who would ever touch her.’

I almost start laughing at this point. They must be talking about Nick Hargreaves, who as far as I know is the only gay member of the team, and incidentally one of the top producers. The idea of Jackie, who thinks she’s so smart, suing the only gay member of the team for what must be sexual harassment just makes me want to laugh out loud. But naturally I don’t, because getting caught eavesdropping in the gents’ is definitely not good form.

TALKING OF sexual harassment, the head of the Paris office was in town today, lobbying Rory ahead of the bonus. I’ve always liked Jean-Luc. He has the widest smile you ever saw, struts like a cockerel in a three-piece suit with a gold pocket watch, exuding a total confidence that he is the handsomest, coolest, smartest man ever to walk the planet (even though he’s overweight and has a shiny bald head and glasses with inch-thick lenses). Only a Frenchman could do this.

Naturally, as he was on expenses, a few of us went out with him after work to catch up on developments in the French market, exchange views on business strategy, compare notes about marketing and origination, and get laid.

Did I say ‘get laid’? I thought I did.

I suppose I owe you an explanation. One of the things about the pressure cooker environment of investment banking is that you need to let off steam. People do that in various ways – drink, drugs, gambling, you name it. In Jean-Luc’s case – being a Frenchman – it’s women. He’s a member of a very exclusive club, called Andrea’s, just off Dean Street in Soho. We piled into a cab and headed off there.

At Andrea’s – where I am not a member – you ring the bell (naturally, there’s no sign outside), wait while they scrutinise you on camera, then get buzzed in and go downstairs to be checked in by giant doormen, who are very respectful, and call you ‘sir’ and ‘gentlemen’, but everyone knows who’s really in charge. Then you go through to a pretty mediocre, dimly lit bar, and pay nearly a grand a bottle for fairly average champagne, which you drink in discreet booths, designed to prevent you catching the eye of the other patrons. Just in case you know them.

Sounds awful, doesn’t it? Well, it is awful, until you ‘go outside’. ‘Going outside’ is shorthand for leaving the bar to visit the other part of the club, where the girls are (and if you’re so inclined, guys too). Of course, being married, I’ve only ever heard stories of what happens when you ‘go outside’. It usually takes Jean-Luc about half an hour, which is not long, and afterwards he just wants to smoke cigarettes and stare wistfully into the fireplace. If he’s in a particularly expansive mood – or wants to get you on side for something, like putting in a good word for him ahead of the bonus – he might invite you to ‘go outside’ too – on his expense account, of course.

Naturally, as a happily married man, I’ve never been outside.

There is a story that when Jean-Luc first joined the firm, he was taken to Andrea’s by one of the old directors, long since departed in some bear market cull, who went outside to find a girl for his guest. When he brought her into the bar to point her in the direction of Jean-Luc, suggesting to her what she might want to do to him, she giggled, ‘Oh, you mean Jean-Luc? I already know what he likes. We all do.’

I did say he was a Frenchman.

Which brings me on neatly to the Kai Tak Convention. If you’ve never heard of it, I’m not surprised, because it doesn’t exist, at least outside of investment banking circles. The Kai Tak Convention is the unspoken code whereby investment bankers on business trips never, ever reveal on their return anything that might – hypothetically speaking, of course – have occurred in the course of their trip. Because that wouldn’t be in anyone’s interest, would it?

It’s rather like the old joke about the patient in the dentist’s chair. Just as the dentist is about to start wielding a particularly nasty looking drill, the patient’s hand shoots out and takes hold of the dentist’s testicles, gently but firmly, whereupon he looks the dentist carefully in the eye, and says, ‘We’re not going to hurt each other, are we?’ Well, investment bankers don’t hurt each other either. At least not when it comes to little things like minor peccadilloes on business trips to Hong Kong, Manila, Bangkok, Moscow, St Petersburg, New York, Milan, Paris, Amsterdam, Stockholm, Helsinki, Berlin, Prague, Madrid…

Anyway, without being crude about it, we get to earn a lot of Air Miles. It’s one of the compensations of the job.

So there we were, sitting in Andrea’s, drinking champagne, with sensual delights by the roomful just the other side of the wall, and what did we do? We talked about the bonus. You know a man is serious about something when he isn’t distracted even by the pleasures that one of London’s top clubs allegedly has to offer. Dedication is the name of the game – at this time of year, we all stay faithful to our purpose.

Anyway, that’s all you need to know.

Tuesday, 2nd November

B minus 44

AFTER LAST NIGHT, I feel rough. I look at myself in the mirror. It’s one of those awful self-awareness moments. I can deal with the lines and the bags under my bloodshot eyes, the shadows and the first grey hairs. I can deal with my paunch, and the way I seem to be perpetually stooping after years spent hunched over a workstation. Those are almost a badge of office. What I can’t deal with is the fact that I’m a loser. I hate my job. I hate my boss. But my biggest fear is that I’ll get fired. Am I fucked up or what?

Don’t answer that – I had a late night and now I’m feeling terrible, so give me a break.

And besides, there’s something else. Last night the dream thing happened again. Rory was running through a forest in the moonlight, the ground covered in snow, working hard so that his frozen breath puffed out in front of him and desperate to escape, but I was faster. I was wearing an ice-hockey mask, overalls and carrying a chainsaw, which roared every time I squeezed the trigger, making him panic, blubber and run all the harder, though he knew and I knew that in the end he couldn’t escape. What happened next is… well, you can probably guess what happened next. Wendy shook me, I was soaked in sweat, the sheets were drenched, and I actually looked at my hands to see if they were covered in blood and bits of gore from where I’d first sliced his arms and legs off and cut open his torso. My hands were actually shaking. I looked at Wendy and wondered if I was really losing my marbles.

I sat for a while on the edge of the bed, and Wendy fetched me a glass of water, though she had to hold it to my lips to drink, because I was shaking so much. She looked at me. I could see the question in her eyes.

‘Just a dream. A bad dream. I’ll be all right in a minute.’

Wendy never questions me. We’re a team. We’re on life’s great journey together, and where I go, she goes.

I couldn’t sleep for the rest of the night, and I looked like shit when I arrived at work. Mercifully, when I looked around the team, I could see I wasn’t alone. There were a lot of other pale faces and dark-shadowed eyes. It’s the time of year. Nick Hargreaves was the worst. If what I’d overheard in the gents was correct, I could understand why. And then I spotted something. On his desk he had a copy of a Christie’s catalogue for an upcoming auction – ‘The Christie’s Africa Sale’. I got up and asked if I could take a quick look at it, and there, on page seventeen, I saw the machete from my dream.

Now this really freaked me out. This was weird. I mean, in the movies, yes, stuff like this can happen – but not in real life. Or maybe I’d seen a poster somewhere advertising the sale. Maybe somewhere in my subconscious I’d registered something without realising it. I looked at the date of the auction: three days before the bonus announcement. Weird.

THERE ARE times when I wish I was Rory. That may sound strange, but it’s true. I happened to be passing his office late this afternoon, when I heard his secretary confirming a business trip for him. Naturally, his chauffeur would pick him up from home to take him to – Biggin Hill! I suppose the name doesn’t mean very much to you. It’s a former Second World War airfield, you might vaguely recall it from watching old movies.

In investment banking circles, it means a whole lot more. In investment banking circles, Biggin Hill has real resonance. It means freedom – freedom from the burden of travelling with the general public on ordinary flights from airports crowded with ordinary people. To us, it means seniority, privilege and success. Biggin Hill means smokers.

Smokers? Let me tell you. A smoker is a private jet, and Rory gets to fly in a GV. You don’t know what a ‘gee five’ is? I’ll explain. The Gulfstream Five is not just any old executive jet. On the team we call it Air Force One. Rory once flew between four continents in twenty-four hours, changing flight crews as he went, juggling the kind of schedule that only global investment bankers can manage. The GV can technically take up to fifteen people, but Rory’s jet is equipped just to take him and up to five colleagues. It goes at Mach .885, and flies at up to 51,000 feet, higher and faster than commercial airliners – public transport – literally leaving them in its wake. The firm doesn’t own it. That might look bad to shareholders. We lease it. So not only does it make Rory’s life more efficient, but it’s tax-efficient too. And it’s very efficient indeed when he wants to get away for a long weekend to relax and reflect on the future direction of the business, in Rhodes or Capri or Monte Carlo, maybe with his wife, maybe without. I’m sure if it was properly costed, we’d realise how much we save by providing Rory with the GV – it’s a bargain and if anyone were ever to ask me – not that anyone would – I’d tell them I’m all in favour of Rory having whatever jet he wants. Or anything else, for that matter, at least this side of the bonus.

Though, in strictest confidence, there is one thing that really pisses me off. I’ve never been aboard the GV. No, not even once. Jackie has. In fact when she first joined, she and Rory used it for a whole load of strategy weekends and off-sites. But these days it looks as if she’s grounded, the same as the rest of us.

Sometimes I feel as if I’m destined to live my life with my nose pressed against the window, a permanent outsider desperately peering in at where the real action is.

‘He’ll be flying alone, and he’d like the same stewardess as last time.’ His secretary’s words say it all – this man has arrived. ‘No, he prefers the ’85 Dom Perignon.’

What can I say?

WHICH BRINGS me to the subject of expenses. In the good old days, it was understood that senior investment bankers didn’t really need to worry about expenses – the market was roaring away, share prices were rising, we were all making money, and expenses were a detail. We actually used to authorise each other’s expenses. An extremely workable arrangement. Today things are different – we live in a tougher climate. Accountants and financial controllers actually have influence, and management listens to them. They have the authority to question things like the two thousand pound bottle of Yquem I ordered at dinner with the Chief Executive and Chairman of Pattison Construction a few weeks ago. The total bill for dinner for four was a little over five thousand, which would not be unreasonable as part of the softening up process of an important client about to award us a major mandate. The irritating thing is that neither of them was actually present at the dinner – yes, I admit, it was one of those dinners, but God knows, we are all guilty of a little exaggeration now and then. Anyway, had they been at the dinner, it would have been a great opportunity to broaden and deepen our relationship. Instead, I took Wendy and her parents to dinner, and must have accidentally used the corporate credit card instead of my own. We’ve all done it from time to time.

The problem now is how to explain. And the worst part of it is that the person I have to explain to is an underpaid, uncouth, unpleasant individual named Samuelson, who thinks people like me are overpaid, arrogant, unreliable and probably dishonest. He’s sent me a note, asking me to justify the expenditure, and copied it to Rory. If I ever find myself in a position of authority, little shits like Samuelson will be toast. Then a light goes on in my head. I have the solution.

I prepare two replies. The first is to Samuelson, apparently copied to Rory.

I GROVEL and schmooze and weasel my way around the issue, saying that the chairman of Pattison Construction chose the dessert wine, and that there were four of them on their side, not three, as originally suggested (I just had a salad, instead of a main course), and pointing out that in fact three thousand pounds (thereby excluding the cost of the Yquem, which I had been obliged to buy out of courtesy for the client) for dinner for five people, of whom four were clients, was expensive, but not totally unreasonable, and had to be seen in the context of the development of the overall relationship, and imminent business prospects which I was not at liberty to reveal to him for reasons of confidentiality relating to price sensitive information. Just the right mix of taking him seriously, flattering him, sharing hints of ‘inner circle’ information with him, apparently treating him as an equal, but then reminding him who generates the revenue around here. And I apparently copied it to Rory, who would also see that I was taking him seriously, which could do his bonus prospects no harm at all. But then my masterstroke – I prepared a second version of the note to Samuelson, which I would actually copy to Rory alone. It was much brusquer, sharper, reminding him of the importance of carefully targeted, well thought through ‘rifle shot’ entertainment of the right people in the right way, emphasising the false economy of entertaining key clients on the cheap, and citing a ten million dollar revenue-generating transaction which we are very close to, but which is still highly competitive. To Rory, this is a reminder that I’m out there playing in the big league, swinging through the corporate jungle with the big hitters, there’s a large deal just around the corner, and I’m not taking any shit from bean counters. When Samuelson fails to challenge me – which he would in a second if he saw this version – Rory will realise who gets respect around here. A masterstroke.

Afterwards, I worry that I’ve never actually met the Chief Executive and Chairman of Pattison Construction – I only know the Finance Director. But I guess that’s a detail.

Wednesday, 3rd November

B minus 43

TODAY my worst nightmare happened. Well, not quite my worst nightmare, but something pretty bad. I got stuck on the Underground. To anyone accustomed to travelling by Tube, this may not sound too frightening – irritating, yes, even inconvenient, but not life-threatening. And for anyone used to living in the Third World country that modern Britain has very nearly become – at least outside the Square Mile – it was almost normal. Except that today we were launching a deal.

Today the European subsidiary of All Nippon Rubber were bidding for the Great Western Chassis Company. The bid would be announced at the market opening and I had to be there, so I left half an hour early to get into work. I didn’t actually have anything to do with the bid, and had never met the client, but it was essential to be around when the deal happened.