10,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

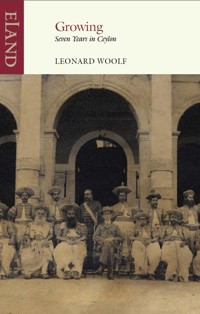

- Herausgeber: Eland Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Growing is the autobiography of a young man sent straight from university to help govern the British Empire. Rarely has an empire had such an intelligent, dutiful, hard-working and incorruptible civil servant. Woolf was determined to do what was good, but discovered for himself that colonial rule was fated to do what was wrong. Growing is a deeply affectionate portrait of the mystery, magic and savage beauty of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) at the beginning of the twentieth century. For Woolf had both the time and the intelligence to explore the country, its diverse religions, beliefs and philosophies, and to pay attention to the differing cultures of the Sinhalese, Tamil and Anglo-Indian communities. He also had the wit to leave a series of devastating portraits of the colonial ruling class.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Growing

Seven years in Ceylon

LEONARD WOOLF

Si le roi m’avoit donné

Paris sa grand’ ville

Et qu’il me fallût quitter

L’amour de ma vie!

Je dirois au roi Henri

Reprenez votre Paris;

J’aime mieux ma mie, o gué,

J’aime mieux ma mie.

Contents

Foreword

I have tried in the following pages to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, but of course I have not succeeded. I do not think that I have anywhere deliberately manipulated or distorted the truth into untruth, but I am sure that one sometimes does this unconsciously. In autobiography – or at any rate in my autobiography – distortion of truth comes frequently from the difficulty of remembering accurately the sequence of events, the temporal perspective. I have several times been surprised and dismayed to find that a letter or diary proves that what I remember as happening in, say, 1908, really happened in 1910; and the significance of the event may be quite different if it happened in the one year and not in the other. I have occasionally invented fictitious names for the real people about whom I write; I have only done so where they are alive or may be alive or where I think that their exact identification might cause pain or annoyance to their friends or relations. I could not have remembered accurately in detail fifty per cent of the events recorded in the following pages if I had not been able to read the letters which I wrote to Lytton Strachey and the official diaries which I had to write daily from 1908 to 1911 when I was Assistant Government Agent in the Hambantota District. I have to thank James Strachey for allowing me to read the original letters. As regards the diaries, I am greatly indebted to the Ceylon Government, particularly to the Governor, Sir Oliver Goonetilleke, and to Mr Shelton C. Fernando of the Ceylon Civil Service, Secretary to the Ministry of Home Affairs. When I visited Ceylon in 1960, Mr Fernando, on behalf of the Ceylon Government, presented me with a copy of these diaries and the Governor subsequently gave orders that they should be printed and published.

I

The Voyage Out

In October 1904, I sailed from Tilbury Docks in the P&O Syria for Ceylon. I was a Cadet in the Ceylon Civil Service. To make a complete break with one’s former life is a strange, frightening and exhilarating experience. It has upon one, I think, the effect of a second birth. When one emerges from one’s mother’s womb one leaves a life of dim security for a world of violent difficulties and dangers. Few, if any, people ever entirely recover from the trauma of being born, and we spend a lifetime unsuccessfully trying to heal the wound, to protect ourselves against the hostility of things and men. But because at birth consciousness is dim and it takes a long time for us to become aware of our environment, we do not feel a sudden break, and adjustment is slow, lasting indeed a lifetime. I can remember the precise moment of my second birth. The umbilical cord by which I had been attached to my family, to St Paul’s, to Cambridge and Trinity was cut when, leaning over the ship’s taffrail, I watched through the dirty, dripping murk and fog of the river my mother and sister waving goodbye and felt the ship begin slowly to move down the Thames to the sea.

To be born again in this way at the age of twenty-four is a strange experience that imprints a permanent mark upon one’s character and one’s attitude to life. I was leaving in England everyone and everything I knew; I was going to a place and life in which I really had not the faintest idea of how I should live and what I should be doing. All that I was taking with me from the old life as a contribution to the new and to prepare me for my task of helping to rule the British Empire was ninety large, beautifully printed volumes of Voltaire* and a wire-haired fox terrier. The first impact of the new life was menacing and depressing. The ship slid down the oily dark waters of the river through cold clammy mist and rain; the next day in the Channel it was barely possible to distinguish the cold and gloomy sky from the cold and gloomy sea. Within the boat there was the uncomfortable atmosphere of suspicion and reserve that is at first invariably the result when a number of English men and women, strangers to one another, find that they have to live together for a time in a train, a ship, a hotel.

In those days it took, if I remember rightly, three weeks to sail from London to Colombo. By the time we reached Ceylon, we had developed from a fortuitous concourse of isolated human atoms into a complex community with an elaborate system of castes and classes. The initial suspicion and reserve had soon given place to intimate friendships, intrigues, affairs, passionate loves and hates. I learned a great deal from my three weeks on board the P&O Syria. Nearly all my fellow-passengers were quite unlike the people whom I had known at home or at Cambridge. On the face of it and of them they were very ordinary persons with whom in my previous life I would have felt that I had little in common except perhaps mutual contempt. I learned two valuable lessons: first how to get on with ordinary persons, and second that there are practically no ordinary persons – that beneath the façade of John Smith and Jane Brown there is a strange character and often a passionate individual.

One of the most interesting and unexpected exhibits was Captain L. of the Manchester Regiment, who, with a wife and small daughter, was going out to India. When I first saw and spoke to him, in the arrogant ignorance of youth and Cambridge, I thought he was inevitably the dumb and dummy figure that I imagined to be characteristic of any captain in the Regular Army. Nothing could have been more mistaken. He and his wife and child were in the cabin next to mine, and I became painfully aware that the small girl wetted her bed and that Captain L. and his wife thought that the right way to cure her was to beat her. I had not at that time read ‘A Child is Being Beaten’ or any other of the works of Sigmund Freud, but the hysterical shrieks and sobs that came from the next cabin convinced me that beating was not the right way to cure bedwetting, and my experience with dogs and other animals had taught me that corporal punishment is never a good instrument of education.

Late one night I was sitting in the smoking-room talking to Captain L. and we seemed suddenly to cross the barrier between formality and intimacy. I took my life in my hands and boldly told him that he was wrong to beat his daughter. We sat arguing about this until the lights went out, and the next morning, to my astonishment, he came up to me and told me that I had convinced him and that he would never beat his daughter again. One curious result was that Mrs L. was enraged with me for interfering and pursued me with bitter hostility until we finally parted for ever at Colombo.

After this episode I saw a great deal of the captain. I found him to be a man of some intelligence and of intense intellectual curiosity, but in his family, his school and his regiment the speculative mind or conversation was unknown, unthinkable. He was surprised and delighted to find someone who would talk about anything and everything, including God, sceptically. We found a third companion with similar tastes in the Chief Engineer, a dour Scot, who used to join us late at night in the smoking-room with two candles so that we could go on talking and drinking whisky and soda after the lights had gone out. The captain had another characteristic, shared by me: he had a passion for every kind of game. During the day we played the usual deck games, chess, draughts, and even noughts and crosses, and very late at night when the two candles in the smoking-room began to gutter, he would say to me sometimes: ‘And now, Woolf, before the candles go out, we’ll play the oldest game in the world’, the oldest game in the world, according to him, being a primitive form of draughts which certain arrangements of stones, in Greenland and African deserts, show was played all over the world by prehistoric man.

The three weeks which I spent on the P&O Syria had a considerable and salutary effect upon me. I found myself able to get along quite well in this new, entirely strange, and rather formidable world into which I had projected myself. I enjoyed adjusting myself to it and to thirty or forty complete strangers. It was fascinating to explore the minds of some and watch the psychological or social antics of others. I became great friends with some and even managed to have a fairly lively flirtation with a young woman which, to my amusement, earned me a long, but very kindly, warning and good advice from one of the middle-aged ladies. The importance of that kind of voyage for a young man with the age and experience or inexperience which were then mine is that the world and society of the boat are a microcosm of the macrocosm in which he will be condemned to spend the remainder of his life, and it is probable that his temporary method of adjusting himself to the one will become the permanent method of adjustment to the other. I am sure that it was so to a great extent in my case.

One bitter lesson, comparatively new to me, and an incident which graved it deeply into my mind, are still vivid to me after more than fifty years. I am still, after those fifty years, naïvely surprised and shocked by the gratuitous inhumanity of so many human beings, their spontaneous malevolence towards one another. There were on the boat three young civil servants, Millington and I going out to Ceylon, and a young man called Scafe who had just passed into the Indian Civil Service. There were also two or three Colombo businessmen, in particular a large flamboyant Mr X who was employed in a big Colombo shop. It gradually became clear to us that Mr X and his friends regarded us with a priori malignity because we were civil servants. It was my first experience of the class war and hatred between Europeans which in 1904 were a curious feature of British imperialism in the East.

The British were divided into four well-defined classes: civil servants, army officers, planters, and businessmen. There was in the last three classes an embryonic feeling against the first. The civil servant was socially in many ways top dog; he was highly paid, exercised considerable and widely distributed power, and with the Sinhalese and Tamils enjoyed much greater prestige than the other classes. The army officers had, of course, high social claims, as they have always and everywhere, but in Ceylon there were too few of them to be of social importance. In Kandy and the mountains, hundreds of British planters lived on their dreary tea estates and they enjoyed superficially complete social equality with the civil servants. They belonged to the same clubs, played tennis together, and occasionally intermarried. But there is no doubt that generally the social position and prospects of a civil servant were counted to be a good deal higher than those of a planter. The attitude of planters’ wives with nubile daughters to potential sons-in-law left one in no doubt of this, for the marriage market is an infallible test of social values. The businessmen were on an altogether lower level. I suppose the higher executives, as they would now be called, the tycoons, if there were any in those days, in Colombo were members of the Colombo Club and moved in the ‘highest’ society. But all in subordinate posts in banks and commercial firms were socially inferior. In the whole of my seven years in Ceylon I never had a meal with a businessman, and when I was stationed in Kandy, every member of the Kandy Club, except one young man, a solicitor, was a civil servant, an army officer, or a planter – they were of course all white men.

White society in India and Ceylon, as you can see in Kipling’s stories, was always suburban. In Calcutta and Simla, in Colombo and Nuwara Eliya, the social structure and relations between Europeans rested on the same kind of snobbery, pretentiousness, and false pretensions as they did in Putney or Peckham. No one can understand the aura of life for a young civil servant in Ceylon during the first decade of the twentieth century – or indeed the history of the British Empire – unless he realises and allows for these facts. It is true that for only one year out of my seven in Ceylon was I personally subjected to the full impact of this social system, because except for my year in Kandy I was in outstations where there were few or no other white people, and there was therefore little or no society. Nevertheless the flavour or climate of one’s life was enormously affected, even though one might not always be aware of it, both by this circumambient air of a tropical suburbia and by the complete social exclusion from our social suburbia of all Sinhalese and Tamils.

These facts are relevant to Mr X’s malevolence to me and my two fellow civil servants. None of us, I am sure, gave him the slightest excuse for hating us by putting on airs or side. We were new boys, much too insecure and callow to imagine that we were, as civil servants, superior to businessmen. Mr X hated us simply because we were civil servants, and he suffered too, I think, from that inborn lamentable malignity which causes some people to find their pleasure in hurting and humiliating others. Mr X was always unpleasant to us and one day succeeded during a kind of gymkhana by a piece of violent horseplay in putting Scafe and me in an ignominious position.

It is curious – and then again, if one remembers Freud, it is of course not so curious – that I should remember so vividly, after fifty years, the incident and the hurt and humiliation, the incident being so trivial and so too, on the face of it, the hurt and humiliation. One of the ‘turns’ in the gymkhana was a pillow-fight between two men sitting on a parallel bar, the one who unseated the other being the winner. Mr X was organiser and referee. Scafe and I were drawn against each other in the first round, and when we had got on to the bar and were just preparing for the fray, Mr X walked up to us and with considerable roughness – we were completely at his mercy – whirled Scafe off the bar in one direction and me in the other. It was, no doubt, a joke, and the spectators, or some of them, laughed.

It was a joke, but then, of course, it was, deep down, particularly for the victims, ‘no joke’. Freud with his usual lucidity unravels the nature of this kind of joke in Chapter III, ‘The Purposes of Jokes’, of his remarkable book Jokesand their Relation to the Unconscious. ‘Since our individual childhood, and, similarly, since the childhood of human civilisation, hostile impulses against our fellow men have been subject to the same restrictions, the same progressive repression, as our sexual urges.’ But the civilised joke against a person allows us to satisfy our hatred of and hostility against him just as the civilised dirty joke allows us to satisfy our repressed sexual urges. Freud continues:

Since we have been obliged to renounce the expression of hostility by deeds – held back by the passionless third person, in whose interest it is that personal security shall be preserved – we have, just as in the case of sexual aggressiveness, developed a new technique of invective, which aims at enlisting this third person against our enemy. By making our enemy small, inferior, despicable or comic, we achieve in a roundabout way the enjoyment of overcoming him – to which the third person, who has made no efforts, bears witness by his laughter.

Civilisation ensured that Mr X renounced any expression of his innate, malevolent hostility to Scafe and me by undraped physical violence on a respectable P&O liner, but under the drapery of a joke he was able to make us ‘small, inferior, despicable, and comic’ and so satisfy his malevolence and enjoy our humiliation to which the laughter of the audience bore witness. Even when I am not the object of it, I have always felt this kind of spontaneous malignity, this pleasure in the gratuitous causing of pain, to be profoundly depressing. I still remember Mr X, although we never spoke to each other on board ship and I never saw him again after we disembarked at Colombo.

* The 1784 edition printed in Baskerville type.

II

Jaffna

When we disembarked, Millington and I went to the GOH, the Grand Oriental Hotel, which in those days was indeed both grand and oriental, its verandahs and great dining-room full of the hum and bustle of ‘passengers’ perpetually arriving and departing in the ships that you could see in the magnificent harbour only a stonethrow from the hotel. In those days too, which were before the days of the motor-car, Colombo was a real Eastern city, swarming with human beings and flies, the streets full of flitting rickshaws and creaking bullock carts, hot and heavy with the complicated smells of men and beasts and dung and oil and food and fruit and spice.

There was something extraordinarily real and at the same time unreal in the sights and sounds and smells – the whole impact of Colombo, the GOH, and Ceylon in those first hours and days, and this curious mixture of intense reality and unreality applied to all my seven years in Ceylon. If one lives where one was born and bred, the continuity of one’s existence gives it and oneself and one’s environment, which of course includes human beings, a subdued, flat, accepted reality. But if, as I did, one suddenly uproots oneself into a strange land and a strange life, one feels as if one were acting in a play or living in a dream. And plays and dreams have that curious mixture of admitted unreality and the most intense and vivid reality which, I now see in retrospect, formed the psychological background or climate of my whole life in Ceylon. For seven years, excited and yet slightly and cynically amused, I watched myself playing a part in an exciting play on a brightly coloured stage or dreaming a wonderfully vivid and exciting dream.

The crude exoticism of what was to be my life or my dream for the next few years was brought home to me by two trivial and absurd incidents in the next few hours after my arrival. It was a rule of the P&O not to take dogs on their boats and I therefore had to send out my dog, Charles, on a Bibby Line vessel. The day after my arrival I went down to the harbour to meet the Bibby boat. Charles, who had been overfed by the fond ship’s butcher and was now inordinately fat, greeted me with wild delight. He tore about ecstatically as we walked along the great breakwater back to the GOH and, when we got into the street opposite the hotel, he dashed up to a Sinhalese man standing on the pavement, turned round, and committed a nuisance against his clean white cloth as though it were a London lamp-post. No one, the man included, seemed to be much concerned by this, so Charles and I went on into the hotel and into the palm-court that was in the middle of the building, unroofed and open to the sky so that the ubiquitous scavengers of all Ceylon towns, the crows, flew about and perched overhead watching for any scrap of food which they might flop down upon. Charles lay down at my feet, but the heat and excitement of our reunion were too much for him, and he suddenly rose up and began to be violently sick. Three or four crows immediately flew down and surrounded him, eating the vomit as it came out of his mouth. Again no one seemed to be concerned and a waiter looked on impassively.

Millington and I went round to the Secretariat to report our arrival and we were received, first by the Principal Assistant, A. S. Pagden, and then by the Colonial Secretary, Ashmore. Ashmore had the reputation of being an unusually brilliant colonial civil servant and he gave us a short and cynical lecture upon the life and duties that lay before us. Then we were told what our first appointments were to be. I was to go as Cadet to Jaffna in the Northern Province. As I walked out of the Secretariat into the Colombo sun, which in the late morning hits one as if a burning hand were smacking one’s face, the whole of my past life in London and Cambridge seemed suddenly to have vanished, to have faded away into unreality.

I spent a fortnight, which included Christmas, in Colombo and on January 1st or 2nd 1905, now a Cadet in the Ceylon Civil Service on a salary of £300 a year, I set out for Jaffna with a Sinhalese servant, my dog, a wooden crate containing Voltaire, and an enormous tin-lined trunk containing clothes. In those days the journey, even without this impedimenta, was not an easy one. Jaffna, on the northern tip of Ceylon, is one hundred and forty-nine miles from Colombo. To Anuradhapura, the most famous of the island’s ruined cities, which was just about halfway to Jaffna, one went by train. From there northwards the line was under construction, the only section so far opened being the few miles from Jaffna to Elephant Pass through the peninsula. The only way to travel the hundred odd miles from Anuradhapura to Elephant Pass was to use what was called the mail coach. The mail coach was the pseudonym of an ordinary large bullock cart in which the mail bags lay on the floor and the passengers lay on the mail bags.

I had to spend the night at Anuradhapura, and I was asked to dinner by the Government Agent, C. T. D. Vigors, at the Residency. Here I had my first plunge into the social life of a Ceylon civil servant, a life in which I was to be immersed for more than six years, but which always retained for me a tinge of theatrical unreality. There was Vigors, the Government Agent of the Province, an athletic, good-looking English gentleman and sportsman, a very genteel maternal Mrs Vigors, and the tennis-playing, thoroughly good sort, belle of the civil service, Miss Vigors. Then there was the Office Assistant to the Government Agent and the Archaeological Commissioner, and there may have been also, but of this I am uncertain, the District Judge and the Police Magistrate. We were all civil servants. They were all very friendly and wanting to put the new boy at ease. The conversation never flagged, but its loadstone was shop, sport, or gossip, and, if anyone or anything turned it for a moment in some other direction, it soon veered back to its permanent centre of attraction. But we were all rather grand, a good deal grander than we could have been at home in London or Edinburgh, Brighton or Oban. We were grand because we were a ruling caste in a strange Asiatic country; I did not realise this at the time, although I felt something in the atmosphere which to me was slightly strange and disconcerting.

It was this element in the social atmosphere or climate which gave the touch of unreality and theatricality to our lives. In Cambridge or London we were undergraduates or dons or barristers or bankers; and we were what we were, we were not acting, not playing the part of a don or a barrister. But in Ceylon we were all always, subconsciously or consciously, playing a part, acting upon a stage. The stage, the scenery, the backcloth before which I began to gesticulate at the Vigors’s dinner-table was imperialism. In so far as anything is important in the story of my years in Ceylon, imperialism and the imperialist aspect of my life have importance and will claim attention. In 1905 when I was eating the Vigors’s dinner, under the guidance or goad of statesmen like Lord Palmerston, the Earl of Beaconsfield, Lord Salisbury, Mr Chamberlain, and Mr Cecil Rhodes, the British Empire was at its zenith of both glory and girth. I had entered Ceylon as an imperialist, one of the white rulers of our Asiatic Empire. The curious thing is that I was not really aware of this. The horrible urgency of politics after the 1914 war, which forced every intelligent person to be passionately interested in them, was unknown to my generation at Cambridge. Except for the Dreyfus case and one or two other questions, we were not deeply concerned with politics. That was why I could take a post in the Ceylon Civil Service without any thought about its political aspect. Travelling to Jaffna in January 1905, I was a very innocent, unconscious imperialist. What is perhaps interesting in my experience during the next six years is that I saw from the inside British imperialism at its apogee, and that I gradually became fully aware of its nature and problems.

After the Vigors’s dinner, still an innocent imperialist, I returned to the Anuradhapura Rest House where I was to sleep the night and where I had left my dog, Charles, tied up and with instructions to my boy on no account to let him loose. He, of course, had untied him and Charles had immediately disappeared into the night in search of me. He was a most determined and intelligent creature, and not finding me in Anuradhapura, he decided, I suppose, that I had returned to Colombo en route back to London and his home. So he set off back again by the way we had come, down the railway line to Colombo. At any rate, two Church Missionary Society lady missionaries, Miss Beeching and Miss Case, who lived in Jaffna, returning by train from Colombo, in the early morning looking out of their carriage window at the last station before Anuradhapura and ten or fifteen miles from Anuradhapura, to their astonishment saw what was obviously a pukka English dog, trotting along wearily, but resolutely, down the line to Colombo. They got a porter to run after him, catch him, and bring him to their carriage. The result was that, as I sat dejectedly drinking my early tea on the Resthouse verandah, suddenly there appeared two English ladies leading Charles on a string.

The missionary ladies were aged about twenty-six or twenty-seven and I was to see them again in Jaffna. Miss Beeching had a curious face rather like that of a good-looking male Red Indian; Miss Case was of the broad-beamed, good-humoured, freckled type. In their stiff white dresses and sola topis, leading my beloved Charles frantic with excitement at seeing me again, on a string, they appeared to me to be two angels performing a miracle. I thanked them as warmly and devoutly as you would naturally thank two female angels who had just performed a private miracle for your benefit, and in the evening I went off with Charles and my boy to the ‘coach’. It was only about two months since I had left London, grey, grim, grimy, dripping with rain and fog, with its hordes of hurrying black-coated men and women, its stream of four-wheelers and omnibuses. I still vividly recall feeling again what I had felt in Colombo, the strange sense of complete break with the past, the physical sense or awareness of the final forgetting of the Thames, Tilbury, London, Cambridge, St Paul’s, and Brighton, which came upon me as I walked along the bund of the great tank at Anuradhapura with Charles to the place where the coach started for Jaffna.

Over and over again in Ceylon my surroundings would suddenly remind me of that verse in Elton’s poem:

I wonder if it seems to you,

Luriana, Lurilee,

That all the lives we ever lived and all the lives to be

Are full of trees and changing leaves,

Luriana, Lurilee.

One of the charms of the island is its infinite variety. In the north, east, and south-east you get the flat, dry, hot low country with a very small rainfall that comes mainly in a month or so of the north-east monsoon. It is a land of silent, sinister scrub jungle, or of great stretches of sand broken occasionally by clumps of low blackish shrubs, the vast dry lagoons in which as you cross them under the blazing sun you continually see in the flickering distance the mirage of water, a great non-existent lake sometimes surrounded by non-existent coconut trees or palmyra palms. That is a country of sand and sun, an enormous blue sky stretching away unbroken to an immensely distant horizon. Many people dislike the arid sterility of this kind of Asiatic low country. But I lived in it for many years, indeed for most of my time in Ceylon, and it got into my heart and my bones, its austere beauty, its immobility and unchangeableness except for minute modulations of light and colour beneath the uncompromising sun, the silence, the emptiness, the melancholia, and so the purging of the passions by complete solitude. In this kind of country there are no trees and changing leaves, and, as far as my experience goes, there are no Luriana Lurilees.

But over a very large part of Ceylon the country is the exact opposite of the sandy austerity of Jaffna and Hambantota in which I spent nearly six years of my Ceylon life. It is, as in so many other places, mainly a question of rain. In the hills and mountains which form the centre of Ceylon and in the low country of the west and south-west the rainfall is large or very large and the climate tropical. In this zone lies Anuradhapura and nothing in the universe could be more unlike a London street than the bund of the tank in Anuradhapura. Everything shines and glitters in the fierce sunshine, the great sheet of water, the butterflies, the birds, the bodies of the people bathing in the water or beating their washing upon the stones, their brightly coloured cloths. Along the bund grow immense trees through which you can see from time to time the flitting of a brightly coloured bird, and everywhere all round the tank wherever you look are shrubs, flowers, bushes, and trees, tree after tree after tree. And for the next thirty-six hours in the bullock cart all the way up from Anuradhapura to Elephant Pass it was tree after tree after tree on both sides of the straight road. It was a world of trees and changing leaves, and all the lives of all the people who lived in that world were, above all, lives full of trees and changing leaves.

The only other passenger by the coach was a Sinhalese, the Jaffna District Engineer. It was a trying journey. The road from Anuradhapura to Elephant Pass had been cut absolutely straight through the kind of solid jungle which covered and still covers a large portion of Ceylon. If the bullock cart stopped at any time and you looked back along the road as far as you could see and then forward along the road as far as you could see, the road behind and the road in front of you were absolutely identical, a straight ribbon of white or grey between two walls of green. In my last three years in Ceylon, I lived a great deal in this kind of solid jungle country, for it covered half of the Hambantota District where I was Assistant Government Agent. It is oppressive and menacing, but I got to like it very much. It is full of trees and changing leaves, and therefore completely unlike the open scrub jungle of the great treeless stretches of sand which in the south you often find alternating with thick jungle. But it is also quite different from the brilliant luxuriant fountains of tree and shrub in which the villages lie in the Kandyan hills and from the parklike luxuriance of places like Anuradhapura.

Travelling through it by road, all you see is the two unending solid walls of trees and undergrowth on either side of you. The green walls are high enough to prevent the slightest eddy of wind stirring the hot air. The jungle is almost always completely silent. All the way up to Elephant Pass I saw hardly any birds and no animals except once or twice the large grey wanderu monkey loping across the road or sitting in attitudes of profoundest despair upon the treetops. Except in the few villages through which we passed we met scarcely any human beings. In the day the heat and dust were terrific; the bullock cart creaked and groaned and rolled one about from side to side until one’s bones and muscles and limbs creaked and groaned and ached. All you heard was the constant thwack of the driver’s stick on the bulls’ flanks and the maddening monotony of his shrill exhortations, the unchanging and unending ejaculations without which apparently it is impossible in the East to get a bull to draw a cart. So slow was the progress and so uncomfortable the inside of the cart, that the District Engineer and my dog Charles and I walked a good deal, for we had little difficulty in keeping up with the bulls. But at night we lay on the postbags, the District Engineer on one side and I on the other with the dog between us. Each time that the rolling of the cart flung the DE towards my side and therefore on to Charles, there was a menacing growl and once or twice, I think, a not too gentle nip.

I left Anuradhapura at nine o’clock in the evening of Tuesday, January 3rd, and the bullock cart with its broken and battered passengers arrived at Elephant Pass at nine o’clock in the morning of Thursday, January 5th. The town of Jaffna, for which I was bound, was the capital and administrative centre of the Northern Province. It stood upon a peninsula – the Jaffna peninsula – which is connected with the mainland of Ceylon by a narrow causeway, Elephant Pass. As we approached Elephant Pass in the early morning, the country gradually changed. The thick jungle thinned out into scrub jungle and then into stretches of sand broken by patches of scrub. Then suddenly we came out upon the causeway. On each side of us was the sea and in front of us the peninsula, flat and sandy, with the gaunt dishevelled palmyra palms, which eternally dominate the Jaffna landscape, sticking up like immense crows in the distance. Everywhere was the calling and crying and screaming of the birds of the sea and the lagoons. It is an extraordinary change which never lost its surprise, the jet of exhilaration in one’s body and mind when after hours in the close overhanging jungle one bursts out into a great open space, a great stretch of sky and a distant horizon, a dazzling world of sun and sea.