Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

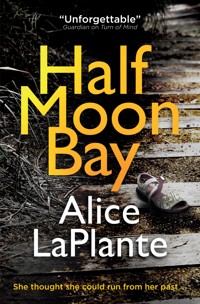

A smart, haunting tale of psychological suspense from the award-winning New York Times bestselling author of Turn of Mind.Jane O'Malley loses everything when her teenage daughter is killed in a senseless accident. Devastated, she makes a stab at a new life and moves from San Francisco to the tiny seaside town of Half Moon Bay. As the months go by she is able to cobble together some possibility of peace. Then children begin to disappear, and soon Jane sees her own pain reflected in all the parents in the town. She wonders if she will be able to live through the aching loss, the fear once again surrounding her, but as the disappearances continue, fingers of suspicion all begin to point at her.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 404

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Part I: Losses

Part II: Trespasses

Part III: Love

Part IV: Choices

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also Available from Titan Books

HALFMOONBAY

HALFMOONBAY

A NOVEL

ALICE LAPLANTE

TITAN BOOKS

Half Moon Bay

Print edition ISBN: 9781785659621

E-book edition ISBN: 9781785659638

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: September 2018

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© 2018 Alice LaPlante. All Rights Reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Did you enjoy this book?

We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at:

[email protected], or write to us at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website:

www.titanbooks.com

All I maintain is that on this earth there are pestilences and there are victims, and it’s up to us, so far as possible, not to join forces with the pestilences.

—Albert Camus

PART I

LOSSES

Six p.m. Fog. Impenetrable, but not cold. Balmy, like Hawaii. That red cottage on the south side of Kauai, near Princeville. Shrouded by eucalyptus, so pungent after rain. Cockroaches scuttled when you pulled back the shower curtain. Where Jane and Rick and Angela stayed their last Christmas. The last year. The last vacation. Last things. So many last things.

As Jane steps outside into the Northern California evening, the fog’s moist veil slaps her face, temporarily obscuring her vision. Dark things loom. Trees, cars. Jane takes off her jacket and tosses it back inside her cottage. The door closes with a click. She doesn’t lock it behind her. No one does, here.

Jane can’t see the ocean from her cottage, but she can hear it and, most important, smell it. She leaves her bedroom windows open when she leaves the house so that when she returns, her pillows are damp and scented of seaweed. Of crabs and fish. Of the larger, mysterious things that swim in the depths. One of the reasons she moved here, to be closer to the sea, that deep insistent body of possibilities. Probabilities.

***

Once upon a time there was a woman. Actually, just a girl, when it begins. One of a family of ten children—first seven girls, then two boys, then a female caboose on the end. Jane is Number 3. Tragedy awaits, but she does not know it. She is being prepared. Everything in her life is building toward this moment. As she is hurt, as she is torn apart, she puts herself in a state of suspension, anything to dull the pain. This is not true, she says; this is not my life. It is her life.

***

Jane’s cell phone rings from within the cottage. She’d set the ring-tone, in a fit of rage one day, on the Dies Irae and never changed it back. The day of wrath. One of her sisters probably. Or a friend from Berkeley, checking in. Her people. Her community. Worried about her, as they should be. But no contact tonight. No.

***

Jane is haunted. Ghosts touch her but deign not to speak. She wakes up in the middle of the night, cold fingers on her shoulder. Others on her arm. The laying on of hands, not to cure but to blame.

***

Jane walks toward the sea, avoiding the surfers’ beach that borders Route 1. Despite the fog and the hour, two or three fanatically fit young men will inevitably be catching waves, sleek as seals in their glistening black suits. Instead, she heads over to Mavericks Beach, the home, when conditions are right, of towering eighty-foot waves, recently discovered by the international surfing set, a place so cool that Apple named an operating system after it. Jane’s go-to place when she is in extremis.

It has now been one year, two weeks, and two days. She can calculate the hours too, if asked. Nobody asks. Nobody refers to it, out of . . . ? Kindness? Courtesy? Fear? It should be fear, fear of wakening the beast smoldering inside Jane.

Jane puts one foot in front of the other. That’s how it works for her these days. The fog so thick she can see only a yard ahead, but she knows every step of this route. Right foot. Left foot. Right foot again. She loses herself in the rhythm. Nothing but the muffled sound of her own steps for a quarter of an hour as she winds through the industrial district of Princeton-by-the-Sea. She is nearing her destination. She can smell the rotting seaweed, hear the plaintive calls of the ringtail harriers from the marsh. Then she stops. Something is wrong. Red and blue lights flicker through the mist. Voices, both men’s and women’s, jumbled and unintelligible. A crackling sound, as of an untuned radio.

***

Jane had lost people before. Joshua, her postcollege boyfriend. She noticed the lesions first. A beautiful bruised purple. Aubergine. On his back and his thighs. And then how thin he was getting. She’d originally thought he was looking good, more fit. She’d even complimented him. But the constant illnesses, colds, flus. And those lesions. One day she woke up before he did. He had his back to her. She couldn’t see his face, but from the wasted body, she understood that she lay next to a dying man. How could she not have known? Her tears wet his shoulder blades, sticking out of his thin back like chicken wings. He had been so kind to her. She had felt safe with him, even loved. It wasn’t until later that it occurred to her that she had been betrayed. She didn’t feel betrayed but bereft. She might have known that this beautiful gift of this beautiful boy would have strings attached. Oh, Janey, he’d said. Oh, Jane, don’t cry. But he had been crying himself.

***

A police car, she can see as it comes into focus. Its lights flashing. White with black geometric markings. And another. And another. A dark figure approaches, grows darker and more substantial as it gets closer.

May I help you, ma’am? When did she turn from a miss into a ma’am? The shift has been imperceptible. Yet it has happened. Maiden, mother, crone. She is no longer either of the first two, so that leaves the final stage. At thirty-nine, her red hair glints gray in direct light.

What’s going on? Jane asks. Even her voice is muffled by the fog.

The figure comes closer. It is wearing a hat, a uniform with a badge on it. It is male, as she should have known from the voice. But somehow that surprises her. What did she expect? Something not quite of this earth. A hobgoblin. Bugbear. But this man seems solid, human. A policeman. The bearer of bad news.

It’s a search party. You live near here?

A silly question. No one lives near Mavericks. To reach it, you have to wind your way through the acres of rusting warehouses and grounded boats Jane has just navigated.

Over there. Jane motions with her head in the general direction of her cottage.

You know the McCreadys, then?

Just the name, Jane says. She tries to conjure up faces, fails.

They live up on the hill. He points into the darkness.

Oh. That explains it. Hill people. They’re different. In another life, Jane would have been one of them. They live in the new houses clinging precipitously to the steep hill above Princeton-by-the-Sea. The ornate ones painted to look like Victorians from the last century. With balconies no one stepped onto, lounge chairs no one sat in. Hill people were the prosperous professionals: the doctors and lawyers and engineers who commuted every day over the hill to Silicon Valley. Another world from here, the San Mateo coast. Although it’s a small community, Jane isn’t on speaking terms with any of the people who live up the hill. Most of them belong to a different species altogether, with their business suits and BMWs that roar off at 7:00 a.m. to make it over Route 92 to Sunnyvale or Milpitas by the start of the workday. Programmers and project managers. Financial analysts, accountants. Men and women who spend more time on the road than at home. People capable of organizing their thoughts into logical code, Gantt charts of responsibility, and numbers that add up. Ambiguity banished from their lives during the day. Then back here, to the rolling sea and amorphous fog. A strange existence. It takes a certain kind of person to juggle the contrasts. Jane knows she sounds scornful, but really she is envious. They have found balance.

What about the McCreadys?

Their little girl, Heidi. She’s wandered away.

Jane considers. Why are you looking here? she asks. It seems an implausible place and time.

This was her favorite spot. She’d been here with her parents this afternoon. The little girl lost her magic pebble. They thought she might have come back to look for it.

Jane considers. Magic pebbles. It hurts to remember. Magic string, magic pencils, even magic bugs. Jane had fixed up a cardboard box to contain the spiders and the roly-polies Angela captured from under the porch, but they all skittered away through the cracks. Jane’s heart breaking to see Angela’s tears of irrevocable loss. A child’s grief, never to be trivialized.

How old was she? Jane asks.

Five.

Angela didn’t speak until she was five. Jane and Rick had taught her sign language and communicated with their hands. Eat. More? All gone. Then, suddenly, out came everything in full sentences. Angela had kept it all inside until she burst. She learned that from Jane.

A long way to walk for a five-year-old, Jane says.

A missing girl. Police. This will end badly. Such things always end badly.

Your name? The policeman has taken out a pad. A pen. He looks at Jane, or at least she thinks he’s looking at her. The fog so thick he no longer has a face.

Jane.

Your last name, ma’am?

O’Malley. Why is Jane so reluctant to give this information? She feels as though she is confessing to something, that he is writing an indictment with his pen right now.

And what are you doing here?

Just walking, Jane says, but it doesn’t sound convincing. Alone, in the dark, in the fog, without a coat or a flashlight, striding along, hands in pockets. She should have brought her landlord’s dog. No one questions you when you’re walking a dog.

I’ll be heading home now, she says, in a voice that sounds deceitful, even to her.

You do that, ma’am, agrees the policeman, but she sees him circle her name on his pad before he turns away.

But Jane doesn’t go home. Instead, she takes a few steps before doubling back and heading toward the sea. She circumvents the official vehicles and walks the dirt path alongside the base of the cliff. Even here she’s not alone. Scores of flashlight beams scan the sand, the bay, the breakwater. The fog is now floating high above her head, wispy threads that glow in the light of the unblocked moon. If Jane were a child, this is exactly the kind of night she’d wander off, excited by the proximity of the sea and the moonlit strands of fog. She’d go straight into this enclosure between the fog and the sand. Straight toward the water. To sink in. To give in. Don’t think she hasn’t considered it.

A seabird calls. Another answers. The sea glows, gives off its own undulating light. Jane sees black heads, unblinking eyes, staring at her from the water. Seals. Selkies. The Celts thought them capable of taking on human form. If a woman wishes contact with a selkie male, she must shed seven tears into the sea. If a man steals a female selkie’s skin, she is forced to become his wife. Selkie women make excellent wives but will always long for the sea. They will abandon everything—home, husband, and, especially, children—if given the chance to return to it.

The fog miraculously clears for a moment, and the stars are so clear Jane can see them twinkle. The air still. Satellites that carry voices and texts crawl slowly across the sky. The moon, full. You must be by the water on such nights. It is best to touch it. Bare flesh to cold water. Jane did this when Angela was small, only then it was the bay, not the ocean. The Golden Gate Bridge shining in the distance as they did their moon dances. Jane had taught Angela to moon-dance, as Jane’s mother had taught Jane and her sisters. And as Jane expected, Angela to teach it to her daughters. Who had remained single little egglets, never united with sperm, unpenetrated, nestled in Angela’s unstretched womb. Not that Angela had been a virgin. No. Just smart about birth control. Jane had taught her that too.

***

Jane reads. Jane goes to a shrink. Jane knows many facts. Are they helpful? No.

Approximately 19 percent of the U.S. population has experienced the death of a child. Almost 1 million deaths annually. This leaves 2 million bereaved parents every year.

The loss of a child triggers more intense grief than the death of a spouse or parent. After the death of a child, the divorce of the parents is a statistical probability. This is science.

Parents who experience the death of a child are more likely to suffer complicated grief. This is bereavement accompanied by feelings of separation and trauma distress. To earn this diagnosis, the person must experience extreme levels of three of the four separation distress symptoms—intrusive thoughts about the deceased, yearning for the deceased, searching for the deceased, and excessive loneliness since the death. They must also show “extreme” levels of four of the eight traumatic distress symptoms: purposelessness, numbness, or detachment, feeling that life is meaningless, feeling that a part of oneself has died, a shattered worldview, assuming behaviors of the deceased, and excessive irritability or anger.

Jane reads: These symptoms result in significant functional impairment.

She has to laugh. No shit, Sherlock.

***

Intrusive thoughts of the deceased.

Intrusive is a good word. Jane commends the psychologists who coined the phrase. Angela intrudes everywhere; each stone, each glass of water, each cup of coffee resonates with memories both bitter and sweet. Is anything just what it should be? A couch, a sweater, a doorknob? No. Angela inhabits every object on the planet that Jane encounters.

Yearning for the deceased.

Oh, how Jane yearns! Even for the last, bad teen years, for the slammed doors and refused plates of food and terrifying nights when Angela borrowed the car. Jane would take any of it now. And the early years! She looks at the few photos she kept, and weeps—what she wouldn’t do to trade places with that younger, more vibrant Jane! The busy and as-yet-uncomplicated mother.

Searching for the deceased.

Jane searches for Angela everywhere. In the house: Is she in the kitchen, making a mess scrambling eggs with butter and leaving the perishables on the counter? In her room, with her earphones on, listening to retro seventies music? On the street Jane constantly sees Angela and hurries to catch up to her, turns corners only to accost startled strangers.

Excessive loneliness

Loneliness: affected with, characterized by, or causing a depressing feeling of being alone.

Excessive: an amount or degree too great to be reasonable or acceptable.

Jane is alone. Utterly alone. The suffering is great, but it is both completely reasonable and absolutely acceptable. She deserves it, after all.

***

Jane has traveled the world, drunk deeply of its joys and sorrows, and landed here, in Princeton-by-the-Sea, a small village on the Northern California coast, a mile north of Half Moon Bay. She is suffering from complicated grief. She is trying to build a life here. She is building a life here, she tells people. Those who know her from her previous life admire her spirit. They exclaim about her resilience. They call and offer their support, but don’t talk about what drove her here. Those who don’t know Jane from before see a sad-faced woman, late thirties, friendly enough although guarded. The most notable thing about her is her hair: a deep, true red. She wears it long and straight, over her shoulders. She is talked about. Thatnew red-haired woman. You know the one.

Jane works in Smithson’s Nursery in Half Moon Bay, the largest town on this stretch of the coast. Her fingernails are often dark from earth when she shops at the Safeway after the nursery closes, buying vegetables that are a riot of color: red peppers that match her hair, dark green cucumbers, light green lettuces, yellow squash, purple eggplants. She is an expert in native California plants, in which Smithson’s specializes. She can tell you whether to plant Big Sur manzanita (Arctostaphylos edmundsii) or Heart’s Desire (Ceanothus gloriosus) in that half-shaded alcove in your garden. If you speak to her, she startles. It is best to approach her gently, as you would a wild faun.

***

Half Moon Bay was once known as Spanishtown. The land was wrenched from the Costanoan Indians in the early 1800s, and Routes 1 and 92 still follow the old Costanoan trails along the ocean and over the hills. A luxury campground, Costanoa, has been built on top of the creekside hollow that was the main Costanoan settlement. Today, tourists feast on roast buffalo and wild pig before going to their “tents,” amid the sand dunes, really small ultraluxurious wooden houses on stilts with shiny bathrooms and king-size beds and down comforters. They do not think of the people they displaced. They do not know the old legends.1 Like when the first person died and began to stink. The meadowlark smelled it. He did not like it. Coyote said: “I think I will make him get up.” The meadowlark said: “No, do not. There will be too many. They will become so many that they will eat each other.” Coyote said: “That is nothing. I do not like people to die.” But the meadowlark told him: “No, it is not well to have too many. There will be others instead of those that die. A man will have many children. The old people will die but the young will live.” Then Coyote said nothing more. So from that time on, people have always died. They are still being buried in the cemetery at the corner of Main and Route 92, the evidence of Coyote’s momentous decision the first thing tourists see as they enter the town.

After the Indians were vanquished, the first houses were raised in the 1840s by Mexican settlers given land grants. Whites began moving in after the Civil War, and after another kind of bloody resettlement, the town officially became Half Moon Bay in 1874, renamed for the perfect crescent-shaped harbor just north of town. Which brings us to one of the peculiarities of Half Moon Bay, and indeed many other Northern California coastal towns. Although situated in one of the most naturally stunning landscapes on the planet, the town center is set half a mile inland, its back to the ocean. The harbor itself is ugly, industrial, at the rear of a seedy mall with a Burger King and destitute variety shops. The town, really only Main Street, is itself quite quaint. Many of the original wood buildings still stand, although the adobes and early brick buildings were destroyed in the 1906 earthquake.

In 1907, the Ocean Shore Railroad was constructed along the shoreline from San Francisco to Tunitas Glen, south of Half Moon Bay. Developers had grand plans to turn Half Moon Bay and its environs into Atlantic City of the West. Plots were sold. Prices soared. Posters depicting bathers venturing into sky blue waters were printed. The developers imagined large hotels, splendid avenues, swank shops. But they hadn’t accounted for the freezing water and thick fog that covered the coast from June through August. No one came. Or if they came, they left hurriedly, shivering. Due to financial problems and the increasing popularity of the horseless carriage, the railroad ceased operation in 1920, the rails long ago ripped up and sold. Now all that remains are the broad streets laid out in large concentric circles facing the ocean in Jane’s town, Princeton-by-the-Sea. The avenues of Monterey pine trees planted to line those streets are now majestic, fulfilling the long-ago vision of a sophisticated playground for tourists, but underneath them are small rotting wood-frame cottages like Jane’s. The former train station is now a Chinese restaurant. It has a decent Mongolian beef, but do avoid the sweet-and-sour pork.

Who lives here? Who would choose this beautiful but remote spot? It isn’t easy to get to where the jobs are—either the long trek up Route 1 to San Francisco or the dangerous trip up and down the steep hill to Silicon Valley. Still, people do live here and are mostly content. There are the farmers, large and small, mostly organic these days. The shop owners, optimistic and typically disappointed by the clientele, who look but do not buy. These come and go. Some stay after their shops close. They like the fact that everyone pretty much knows everyone else by sight and that it’s a safe place to raise kids even though the schools are lousy. Water is scarce, so building new houses has been banned except for the Silicon Valley billionaires who buy up sections of the coastline and bribe the Coastal Commission for permits.

Take a walk now, down Main Street. See Marilyn Standish, the tough proprietor of the tiny coffee shop. She has had a mastectomy but without the reconstruction surgery. That would be vanity, she declared. She is a Seventh Day Adventist and doesn’t let her daughters celebrate their birthdays, although they secretly defy her and eat birthday cake and accept presents in the cafeteria at school. Keep going. See Bob Orlando, who owns Bogies, the grocery store. Downstairs is the usual food and produce. But upstairs, a trove of oddities. You can buy kissing nun salt-and-pepper shakers, authentic fisherman’s hats, books by local authors on the coastal flora and fauna. Everything jumbled in piles and seemingly forgotten for years. An Aladdin’s cave. Joan Acuesta is there now, sifting through the piles of extra-large flannel shirts and pillbox hats from the 1930s for a gift for her niece, whom she has raised from a baby. Unbeknown to Joan, her niece in seven months will give birth to a child of her own. She will refuse to name a father. Such things happen here frequently.

Go downstairs again and out the door. One block to the left, and you get to the Three Sisters Café. Run by three sisters, naturally: twins and their younger sibling. Opened only one year ago, and now the heart of the town. This is where you go to get the best coffee on the coast, the most flavorful artichoke soup, the freshest and most titillating gossip. You can’t see the walls of the café; they are covered with children’s drawings, notices of births and deaths, advertisements for the Coastal Players’ production of My Fair Lady, hot yoga classes by Martha, dog walking by Ian, and other essential services. You could spend a year reading those walls. By doing so, you don’t feel alone. You understand that life is pulsing around you, that even on Sunday nights, when Main Street is deserted and the fog shadows the streetlights, other hearts are beating around you. The wall brings comfort to Jonathan Hummer, who lost his wife to a sudden heart attack in February. He pulls off a paper tab containing a phone number for Ohlone Singles when he thinks no one is looking and puts it surreptitiously in his pocket. He will get a good one this time. He will get one who doesn’t blow cigarette smoke in his face, who can tolerate having dog hair on the living room furniture. He will.

The Beach Belly Dancers are meeting in the assembly room of the old First Methodist Church two blocks south of Three Sisters. They are mostly women of a certain age who would never wear two-piece bathing suits, who make love with the lights out, who buy their clothes on the Internet. Yet here they are, dressed in gaudy silk-like ballooning trousers and sparkling bras, exposing their pudding-like bellies to the world as they shake and whoop and stop to drink some wine or taste one of Janet Thimble’s homemade oatmeal cookies or plot a political coup on the town council. Together, they are a nation, and they are important. When they leave at 10:00 p.m., their shoulders are a little straighter, their steps a little faster. They return to their sleeping families feeling like army generals after a truce has been declared. What to do with all this energy? They sit at kitchen tables and write lengthy to-do lists and strident letters to the editor of the Moon News.

Darkness descends on Half Moon Bay. Fog mixed with smoke from wood stoves hovers above the houses. The surf pounds the sand, a full half-mile from Main Street, but the rhythm of the sea and its tantalizing scent permeate the porous window frames of the old wooden houses, soothing the inhabitants, luring them to their beds. They know they live in a bubble. They know that dark things, unimaginable things, wait in the wings for their turn to propagate and thrive. The Costanoa’s Coyote, the trickster, will ascend again, in more alluring form, in retribution for past sins. But for now, the town sleeps, content in its innocent ignorance.

***

That night, Jane can’t stop thinking about little Heidi. This is unusual. Jane has gotten good at not thinking. She has gotten very good about not feeling. She settles on her couch with a book, something a previous tenant left behind, the cover art portraying a bosomy sorceress fighting an army of horned beasts. But Jane can’t concentrate. She’s agitated. She thinks about the distraught parents. If she had sufficient generosity, she’d walk up the steep hill, offer to sit vigil with them. She’d tell her story. She’d reassure them that everything would almost certainly turn out all right. For them. And she’d be lying and secretly reveling in it. She considers the scenarios the parents are inevitably conjuring as they await news. Jane pictures Heidi as the little Swiss mountain girl in Angela’s version of the book by that name, snub-nosed with blond braids, puffed-out white sleeves, and an embroidered dress. Jane goes to bed and dreams of Heidi, safe on her mountain picking bluebells.

***

There is little talk of anything but Heidi at the Three Sisters Café, where Jane gets her coffee the next morning.

Have you heard? asks one of the young café owners as she refills Jane’s cup. Jane has finally gotten to where she can tell the sisters apart, they look so similar, even though only the two older ones are twins. They share a pale oval face with small dark eyes. They look like marmots, with their manes of dark hair caught up in ponytails, their large blue unblinking eyes. Somewhat feral, but nevertheless approachable. Sympathetic.

It is a closely knit community, and although this misfortune has hit outsider over-the-hill people, locals are feeling it deeply, Jane can tell. Voices are subdued. Children too young to be in school are being hugged close by their parents.

They’re organizing a search party, said the sister, her name is Margaret, on her next trip around the tables. Sign up at the sheriff’s office. Jane can’t—she has a job to do; she is, despite her fragile state, gainfully employed—but she leaves Margaret an extragenerous tip in recompense. People nod to her as she leaves. It’s that kind of place.

***

As it turns out, Heidi is dark-haired. She is not adorable. It is not an attractive photo that appears on the signs on the street, in the shop windows, in the Moon News. How can a five-year-old girl be so plain? Jane remembers Angela, her friends at that age, so heart-stoppingly lovely, the mothers universally convinced that strangers would be tempted to snatch them away if left unguarded for even a moment. So they weren’t. A generation of tiny prisoners.

***

Sometimes Jane walks, and talks, and acts as if she were still a mother, still a woman with a family, not a woman alone. A mother walks slower. She has much on her mind. Where is the daughter? Who is she with? What is she doing? And, most important, what could go wrong? A woman without a family is lighter on her feet, less distracted. She’s not thinking, Nearly dinnertime. What shall I feed her? Or see a dress in a window and stop and think, Wouldn’t she look cute in that? before reality sets in.

***

Two days pass. Three. People start shaking their heads in the Three Sisters Café. This will end in tears, Jane would tell Angela when, as a child, she played too roughly with her toy soldiers, her Barbie princesses, in an all-out war of the sexes, the pink bosomy Barbies overwhelming the small green plastic soldiers. Rick’s idea of bringing Angela up without gender biases. Jane walks past the photos of the singularly unattractive Heidi papering the windows of the stores along Main Street. This will end in tears.

***

Jane is not a believer in Dr. Kübler-Ross. The five stages of grief do not exist. Or rather, they are not stages. Or rather, they are not grief. They are madnesses. Jane accepts the fact that denial, anger, bargaining, and depression are now her life. Acceptance is not, nor will it ever be. Always a maker of lists, Jane has created an Excel spreadsheet on her laptop. She checks off the madnesses as they engulf her minute by minute, day by day, on a scale of 1 to 10. Is what her shrink calls the intensity dissipating? Jane’s shrink says yes; her spreadsheet says no.

Kübler-Ross missed some of the most important madnesses. Shame. Guilt. Hope. And yes, ecstasy. Sleep can bestow glorious gifts, as when Angela arises, whole and unmangled, acting as though nothing has happened. What’s for dinner? she asks. Or, Can I have the car? Or, worse, just a plain inquiring Mom? Then Jane wakes, and it is like hearing the news for the first time.

***

How do you define loss? Jane has posted Merriam-Webster’s definition on her bedroom mirror. Deprivation. She has been grievously deprived.

***

Here’s what Jane remembers. Heat. Even for July, it had been unusual. All the climatologists saying Get used to it. A hotter world. An increasingly inhospitable planet. Berkeley was certainly hostile that summer, if Jane remembers properly, if she is not fantasizing, if she is not transforming emotions into facts, as her shrink often accuses her of doing. You are the unreliable narrator of your own life. Yet surely it is true that at that time, the garbagemen are on strike, and stinking refuse is piling up on the street, overflowing onto sidewalks. Fans sell out at the hardware stores, as do rat traps. People stop picking up their dogs’ poop. The homeless, who refuse to shed their layers of clothing no matter how hot the temperature, are passing out from heatstroke and dehydration. The university lets them bathe in the fountains, an unusual concession of humanity. And then there is that night, when Jane sits in her living room waiting and worrying. No, she is not psychic. This is simply what she does when Angela is out at night. Where does this fear come from? She had grown up in a middle-class family in a safe middle-class town. Was the word fear? No. Terror. She waits, terrified, night after night.

When the police car pulls up in front of the house— of course, her curtains are open, of course, she makes sure she had a clear view of the street and sidewalk— you could say she was prepared. Jane had anticipated this day from the moment of Angela’s birth sixteen years ago. She hadn’t known what the details would be, of course. There were so many possibilities! But the two uniformed men who tread heavily up to Jane’s door fit in well enough with her fantasies. Yes. It could happen like this. Yes, it could. And then the knock on the door.

***

It is 2:00 p.m. at Smithson’s Nursery, and no one has taken lunch yet. Mid-August, time to start gearing up for the annual Pumpkin Festival, the biggest weekend in Half Moon Bay, when people come from all over the state to get lost in corn mazes, drink local designer wines, and pick out their pumpkins for Halloween. Children choose their own pumpkins from the piles of small pumpkins. Parents look for the biggest and most symmetrical to carve into leering faces. At the end of the weekend, they drive home, a pumpkin nestled below each pair of feet like a small pet. Smithson’s doesn’t sell pumpkins, but from experience knows that tourists will also swoop on any plants that flower in autumn. There has been talk of canceling the Pumpkin Festival because little Heidi has not been found. But the talk is not serious. The Pumpkin Festival is essential to the health of the local economy.

Jane likes watching her colleague Adam as he digs up tiny shoots of pepperweed (Lepidium lasiocarpum) from a seedling tray. He is pleasant to look at, his fingers brushing dirt off the leaves, deftly inserting the tiny plants into the larger plastic pots. He’s got one earpiece in, listening to dreamy neo-hippie music that would put Jane to sleep in a moment. Even half hearing it, combined with the somnolent humidity of the greenhouse, makes her drowsy. Adam’s long body is bent over the rough wooden table, over the plants he has nurtured from seeds, his longish blondish hair brushing the green tops. They’re among Smithson’s best-selling ground cover. Suddenly he stands up straight. Dirt falls from his fingers. His eyes are wide. He presses the earpiece closer. The Big Kahuna! he says. Surf’s up! He’s already got one hand out to grab his jacket off the back of the chair and the other hand starting to unbutton his shirt.

Whoa there, cowboy, says Helen Smithson, the owner of the nursery, but she’s laughing like the rest of the staff. Adam keeps his wet suit and surfboard in the back of his aging Volvo wagon, and he changes into it by semicrouching in the parking lot. If you think, as many of the staff do, that Adam looks good in his jeans and T-shirt, you should see him in his wet suit. You should see him out of his wet suit. He’s oblivious to the attention.

Adam has been making noises lately that he wants to be friends with Jane. She hasn’t decided if she’s ready to let anyone into her life, especially someone as sunny and seemingly uncomplicated as Adam.

***

They find little Heidi McCready eight days after she disappeared. Her body discovered by the side of Route 1 just south of Montara, in a field of late-blooming tiger stripes (Coreopsis tinctoria).

She had been carefully, even lovingly, wrapped in a woven Indian-style blanket, the kind they sell at the San Gregorio Store and a thousand other places in the Bay Area. Nothing unique about it. Her black hair had been combed and tied back with a pink ribbon. Most disturbingly, her eyes were open, and she had been made up expertly with foundation, rouge, and lipstick, nothing excessive, but enough to make her appear still alive and blooming to the teenagers who’d found her. According to the Moon News, they’d tramped through the field on their way to a grove of Monterey pines that was a popular high school party site and literally stumbled across her, a small figure lying flat, peacefully contemplating the night sky.

***

What? Why? Who? There are nothing but questions. The town is horror-struck. But Jane welcomes a sort of equilibrium: for once, the atmosphere in the external world mirrors her internal darkness. The weather cooperates, serving up wind and fog and pelting rain that feels like tiny bullets to the face. For the first time in more than a year, Jane feels human again, connected to others of her species by a common grief.

***

The loss goes forward as well as back. The loss of what would have been in addition to mourning what was lost. Today Angela would have been seventeen. She would have started her senior year in high school, would have been applying to college. Jane is looking ahead at grim milestones of this kind for decades. By now, Angela would be graduating from college. By now, advancing in her career. What would she have done? Jane would have bet on a scientist. Angela, underneath her teenage rebellion and emotionalism, possessed a fact-centric personality. Jane would never have dared to make an argument without backing it up with numbers. A data-driven girl.

• The average teenage hours per day spent goofing off: 5.81. (See! I’m not weird!)

• The most valued or essential relationship for high school students: their mother (47 percent). (Angela hated that one.)

• Percentage of high schoolers who have had sex: 41.2 percent. (So there.)

• Twenty-nine percent of teens have posted mean info, embarrassing photos, or spread rumors about someone on Facebook. (That doesn’t make me feel any better.)

Not that any of this helped much in the combative teenage years. But it held out hope for the future. A future that didn’t exist anymore.

***

The Moon News says the police are not releasing the cause of death, but the buzz at Three Sisters, always on the money, is that there weren’t any apparent wounds or injuries. Nothing that marred Heidi’s appearance, as unprepossessing in death as it had been in life.

That poor kid, says Helen to Jane quietly the morning the news broke. That poor poor family. Already, a shrine has appeared, a large one, with a statue of Our Lady of Guadalupe and hundreds of bouquets of flowers strewn at her feet alongside Route 1 near the field where little Heidi was found. Half Moon Bay has never experienced a child abduction, much less a child murder, in anyone’s living memory.

Jane is conflicted. She should be ashamed to feel joy in someone else’s misfortune, yet the inevitable schadenfreude has raised its ugly head. I told you so. The madnesses descend, one by one. Jane takes out her spreadsheet, and with shaking fingers, types 10s in all the cells. She calls her shrink for an unsatisfactory session of hand-holding. But the madnesses have taken over her world.

***

Naturally the teenagers who found Heidi documented the scene with their cell phones; that’s what this generation does. They order a meal, they take a photo and post it. They find a dead body, they do the same. The police tried to clamp down on the distribution of the crime scene photos, but it was too late. Jane sees the phones being taken out at the Three Sisters, studied, handed around, but manages to decline with a semblance of sanity when someone offers to show her what’s on one of them. She’s seen it all already.

Jane held her own child like that, just so. What remained of Angela had also been carefully wrapped in a blanket. We’ll leave you alone, then, said the doctor, and she and the nurses exited the room. Jane’s daughter’s upper torso was intact but cold. She had inherited Jane’s bright red hair from some long-ago Irish ancestor. Her eyes so black you could barely see the irises. Yes, they were open too, Jane could see herself reflected in their dark depths. A modern Pietà. Jane did not look any place but Angela’s face, miraculously unscathed. The doctors had been considerate. What was left of the lower body had been tightly wrapped in hospital linens. Jane remembers swaddling Angela as a colicky infant, wrapping the soft cotton blanket tightly around the small, furious, kicking red body. Jane knows she should be in sympathy with Heidi’s parents, but she isn’t. She has more in common with the murderers. She’s killed, and then held the victim of her deed in her arms. Somehow Jane knew this had been the case with little Heidi as well. She had been loved to death.

***

Jane studies the photo of Heidi on the front page of Moon News—the same photo that was on the flyer distributed after her disappearance. The parents werelucky, Jane thinks, that Heidi was taken at this age and not later. The McCreadys’ grief was pure, unblemished by disappointment or bitterness that would have inevitably arisen as Heidi grew older. None of Jane’s friends with teenage children were altogether happy with their choice to reproduce. The ones with full-grown adult children even less so. The worry! The pain! If I had known then what I know now, they had told each other at book club meetings and coffeehouses, only half joking. What an idiot I was, thinking I needed to have children to be whole, they’d say. I wish I could write a letter to my younger self, explaining how wrong she was. Jane had been one of them, the regretful, complaining mothers. She had that on her conscience too.

***

The police are everywhere. Not just the limited Half Moon Bay police force, but San Mateo County sheriffs are making the rounds. They are interviewing everyone. There is word that the FBI will be coming in, forming a task force, because of the child kidnapping angle. Something about the Lindbergh Act. But the two men in uniform who come to Jane one afternoon at the nursery are locals.

Jane recognizes one of the cops by his voice. It is the one she’d spoken to the night Heidi disappeared, the one who circled her name on his pad. She can finally see his face clearly. He is much younger than she would have guessed. An unlined, untested face, and therefore one not to be trusted. Jane finds herself ill at ease these days with those inexperienced in life. Does that include children? It does.

You said you didn’t know the McCreadys, the policeman begins abruptly. No social niceties.

Jane is carefully wiping the leaves of the lilyturf (Liriope spicata) plants to keep them moist. Each leaf coming out a deep pure green after her wet cloth passes over it. She continues what she is doing. She breathes in deeply, as she’s been taught to do in times of stress.

I didn’t. I mean, I don’t, Jane says, finally. I knew that people with that name lived up on the hill, but I’ve never spoken to them.

But you have. This was the other cop, the one with the San Mateo Sheriff’s Department patch sewn on the shoulder of his uniform. If it wasn’t an interrogation, Jane would have warmed to this man. He reminds her of Rick, with his narrow blue eyes and sandy-colored hair that curls around his ears. A deep quietness that reassures.

They came here and bought some plants from you. Quite a large order. They remember you distinctly. Your red hair. Your boss remembers them too.

Jane feels trapped. She’s never been good with authority figures. She invariably feels guilty of whatever has occurred. She is willing to admit to anything anyone accuses her of. In middle school, when her teacher called her to the front of the room to commend her on an essay she’d written, Jane blurted out, I didn’t plagiarize! Which of course caused the teacher to treat her with suspicion thereafter. Jane learned not to say what she was thinking, instead tried hard to look nonchalant and innocent when lunch money went missing or obscene graffiti was scrawled on the gym walls. But she’s not a good actress and can’t always force herself to do what liars apparently did to convince people of their innocence. Look people in the eyes. Don’t swallow. Don’t put your hand near your face, especially don’t hide your mouth or eyes. Don’t make any grooming gestures. Jane had practiced not lying in the mirror. She was terrible at it. Her hand was always straying to her face, and she always hesitated and swallowed before answering even the simplest questions. Jane would appear a liar even if asked for her name, or her favorite color.

When was this? Jane knows it sounds like she is buying time. She is.

Last January. January fifteenth, to be exact.

Jane considers what to say.

I was not . . . myself . . . back then, she says. I had only just arrived here. A lot of things from that time are a blur.

The nicer-looking policeman nods in what could be interpreted as a sympathetic manner.

Nevertheless, it was a little odd to find you wandering alone in the dark the night the little girl disappeared, he says. At that place, at that time.

I often wander in the dark. Especially to that place. Especially around that time of night.

Even though the beach closes at sundown?

Not to locals, Jane says. Not to me.

This makes both cops stop and look more closely at her.

You’re somehow privileged? the friendly one finally asks without hostility, just interest, it seems to Jane.

You know you could be ticketed for trespassing after hours, says the other, at the same time. He is hostile, Jane decides.

Yes, and yes, says Jane. But it’s not patrolled, and everyone knows it. Then, fiercely, You’re wasting my time. She turns her back on the cops to tend to her lilyturfs. She’s learned, over the last year, that being rude rather than polite, pushy rather than obsequious, gets her what she wants: to be left alone.

But it doesn’t work. The questions continue.

Where were you earlier that evening? (Home.)

Can anyone vouch for you being there? (No.)

What were you doing? (Straightening up. Organizing stuff. Reading.)

Do you have a car? (No.)

How do you get around? (Motorbike.)

Her answers to the last questions seem to terminate their interest. We might have more questions for you later, the friendly cop says finally, and they turn to leave, but not before the unfriendly cop plucks a glorious white rose from one of Helen’s prize bushes and holds it to his nose.

Why don’t flowers smell like anything anymore? he asks no one in particular.

Jane considers this a victory.

***

Despite all the police activity, no plausible suspects emerge. No one is charged. It must be a stranger, people say. They view anyone who recently moved to the coast with suspicion. There haven’t been many of them. The Schroeders, a boisterous family of six. The parents opened a frozen yogurt store on Main Street six months ago, are wonderfully patient with all the kids who hang out there. Greg and Jim, a young cohabiting couple, doing something in the arts scene up in San Francisco, and frequently away on trips. A few other unlikely persons. No single older men, normal or strange. Everyone in couples or families. No weirdos, unless you count the ones who have lived here for years. And Jane of course. Jane tries to look innocent. She tries to look concerned. She keeps her hands away from her face, doesn’t pat her hair. But she feels the burden of the unasked questions. Who are you really?

***

The faces of the townspeople, the shopkeepers, are grim. This is when the coast typically gets its most beautiful weather, but even that isn’t cooperating. The usually joyous preparation for the big Pumpkin Festival scheduled for the third weekend in October have begun, but sotto voce. Posters are being placed around town, fields mowed, pumpkins harvested. Local stores are gearing up for their busiest time of the year—pumpkin harvest brings in even more than Christmas—but everyone is subdued. Fewer families come to the beach on weekends, fewer customers from over the hill stop by Smithson’s on their way home. The sky is a metal gray and the wind chills you even if you’re wearing layers. Jane shivers as she rides her motorbike to and from work. Bad juju is in the air.

***

Jane is kneeling by the side of Route 84. Five hundred yards west of the old San Gregorio Store. Within spitting distance of the Pacific Ocean. Tending the roadside memorial that’s been here for nearly a hundred years. A small wooden cross. A teddy bear and a companion stuffed rabbit. And always fresh flowers. This is one of Jane’s secret places.