Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: BoD - Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

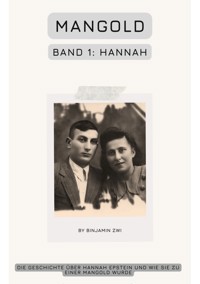

The Berlin Jew Hannah Epstein and her great love Hans Mangold luckily survived the Nazi extermination of Jews in the Berlin underground. Hans' father, who was presumed dead, runs an asset management business in Switzerland, brings Hans into the Business, and he soon brings his Hannah to Switzerland with him. They married in August 1952; Their son Samuel was born in November 1952. It is the story of Hans, Hannah, and Samuel, told by Hannah, a story of fairytale wealth and happiness. But it's not a fairy tale. It is Hannah's life story, recorded by one of her descendants from a draft in her estate.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 404

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Introduction

[

02 Sarah, Hannah, Ari]

New life and the move

[

03 Villa Mangold Basel]

Engagement in Berlin

Zurich: new home, our company

[

04 Grand minster at Zürich]

The wedding

The birth/the growth

The youth center and the years afterwards

[

05 Freiburg 1960]

Move to Freiburg

[

07 Villa Mangold]

Family, grandchildren: Elias, Aaron and Leah

[

09 Freiburg Synagogue]

YOUNG FAMILY (1952–1975)

YOUNG COMMEMBER (1976–2008)

This book I dedicate to our beloved Hannah (* 1934, † 2017)

INTRODUCTION

My name is Hannah. I am Jewish. I mention it right at the beginning because it has shaped my life. And this book is about me and my life - a completely happy life, even if it did not seem that way at first. But then success became evident, and today we belong to the upper class.

Our happiness became visible to everyone when my husband, Hans, and I bought one of the most beautiful villas in Freiburg. At that time, it was named Villa Else, after Else Weil, who once lived there with her husband. Now I am sitting here at my desk in Villa Mangold, which now bears our last name, writing this book in my elegant study and letting my life flow freely.

Today, it is a normal feeling to move freely on the street as a Jew. No one pays attention, and Jews are no longer humiliated in public. Only I know who I am and that my freedom is anything but self-evident today.

Of course, anti-Semitism has been around for a long time. It has embedded itself deeply and firmly in large parts of society. Has established itself there as a bacillus. So, no one should think that we have finally overcome this form of barbarism. Some people had and still have their prejudices, but few put these prejudices into practice. But that has become rare today. In such cases, there will soon be a social outcry.

But when I was a young girl, people were not just persecuted because of their background; no, they murdered them for it. It was not even that long ago. I remember that very well. I was about 12. It will forever be in my bones, no matter how peaceful the circumstances become.

I was a beautiful girl, ready for my first love. But nothing came of it. A nightmare came true when the war started. My people were hunted down, kidnapped, and mostly murdered, even though we were not a warring party at all. So many men, boys and girls, but also mothers and fathers, were brutally murdered—until the last days of the war when the war had long been lost.

My family and I were lucky. Together with a few others, we escaped a death line, hid, and survived this terrible time.

We had been kidnapped from our home and treated like dirt by the Nazis. Some were murdered because they refused to leave their homes. We were sent to so-called resettlement camps and then herded into railway carriages like dirty, smelly cattle. There were so many people in one car that you couldn't sit down or go about your business. They just let it go and tried to survive. With a bit of luck, the survivors were sent to an internment camp. They didn't know that death also lurked in the internment camps.

We were lucky. Our train was attacked by fighter planes and derailed, and we escaped. We sought shelter in an abandoned mansion, and a small group of us ventured back to Berlin. There was a shelter there. Many of us survived there, thanks to our hero, Eliam Katzenstein. He was the leader at the shelter and welcomed us.

Karl, a young Wehrmacht soldier, even killed a comrade to save Eliam Katzenstein and Adam, my brother. Karl and Eliam had been best friends before the war and had sworn to each other eternal friendship by their blood. Karl proved his loyalty by killing our enemy, even if it was only one soldier.

At that time, when Eliam heard the shot from Karl's gun, he first thought that Karl had shot himself, and he and Adam remained in this belief for years, for they fled as fast as their legs carried them. It was only in the last days of the war that Eliam found out that Karl was still alive, and now Eliam has saved Karl’s life.

Karl was deserted because he saw no point in a worthless war and had never wanted it. He was captured and was to be attached to one of the lanterns in the Wilhelmstraße near the Reichskanzlei. But he stumbled and almost starved to death in front of Eliam's vehicle, but managed to escape in the bomb hole. Because the soldiers who were supposed to hang him were almost all young, they fled. They left Karl behind with unfinished things.

Yes, Eliam was our hero. But he did not want to hear that. After the war, he went to Holland to find his girlfriend, Rachel.

Even in an era of horror, time does not stand still. Despite all the threats, life must go on. Whoever wants to survive the whole thing and eventually be among the survivors must never give up. There are always allies and righteous ones. They will not be left alone, but they will find allies, even righteous ones. I found my beloved husband, Hans Mangold, in the struggle for survival. I married him later.

There were also good people, like the peasant couple Adaja and Gustav, who helped us a lot. We had to have something to eat. Gustav and two other farmers from the outskirts of Berlin gave us what they could be lacking. The two have grown very close to our hearts. It was only later that I learned that Gustav had also saved Adaja from the Nazis. She was Jewish, and he was an evangelical Christian. An allied priest married the two and provided Adaja with false papers. Since then, her name has been Marta, but in her heart, she remains Adaja.

Without Adaja and Gustav, we would often have starved, and I would never have met Hans. The two found him almost dead in the forest and kept him healthy. We took him to the shelter. It was love at first sight. The two also took Eli with them. His family was murdered by the Nazis. Eliam had saved him and given him a home in the refuge. Eli was snorted in Adaja, and once we got food there, he decided to stay with the two. Eli became her son. That was the best thing for him, and they also helped him not to be bitter in the face of his difficult fate. Eli became a fabulous man. He still lives with his family on his parents' farm and is a cattle breeder. The rural region around Berlin offered itself at the time and still offers itself very well today.

After we had survived the war and Eliam Katzenstein (God bless him) had agreed with the Russian commander, Marshal Konstantinovich, we were finally free again! Because of Eliam's remarkable negotiating skills, we got from Marshal Konstantinovich an old camp, which had served youth recreation before the war. There, we relaxed and built our community. Today, there are only the remains of the wall. The GDR did not want to remember our history. The Jewish flag with our David star has long been out there.

What a feeling it was to suddenly walk underground through the bombed streets of Berlin after so long! Well, it was a precarious freedom, and we only owe it to the Russian liberators. If it had gone after the Germans... We Jews were no longer murdered, but they hated us nevertheless, even more than before, because we knew now what they would have done to us if they had not been handled at the last moment.

We saw it in their eyes when they saw our shattered figures, and they did not allow themselves to take relevant comments such as, for example, “Na! Have you been forgotten? The furnaces are still burning in Auschwitz!" Not everyone wanted to know about it later, but at that point, everyone was well-informed. They couldn't say they had a fist behind their back because they wouldn't have been able to resist. No, that is not all true, and they do not think differently today; they do not trust each other anymore.

Or that old, bitter Nazi widow from our neighborhood who poured a bucket of ice-cold water out of her window on us. I will never forget that. I still felt the cold shock today when I dropped the water. She was the one who always insulted me as a Jew. Just because I was wearing a black dress that no longer looked nice.

Jews wore most of their clothing in black. Black suit, white shirt, and vest. Depending on the faith, the head covering is either a kippah or a Schtreimel. Women wore or still wore black dresses with long sleeves and a black knitted jacket. The head cover is either a wig (Scheitl) or a scarf, depending on the faith. (We Jews also refer to an older coat or dress that no longer looks as good as a Jewish skirt.)

We wanted to move back to Levetzow Street, where we had lived before the war, but there was nothing like it once was. The synagogue was almost destroyed. It was also not restored or demolished by the DDR authorities in the 1950s. But for so long, she stood there and was—inaccessible and profaned for us—a constant silent reminder of our destiny!

As a child, I always went there with my family. We prayed, met our friends, and discussed our religion with Rabbi Lewkowitz. It hurt me to see my synagogue looking so destroyed before our eyes.

(In 1960, a wall with a memorial plaque was erected. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, I was at my synagogue and was shocked. From a religious place, it has become a playground and a bowling field. In 1988, a steel flame wall, a ramp, and a wagon were erected on only half of the plot, with figurations abstractly depicting 'human packages' knotted in iron. Thank you!)

Otherwise, the East and the GDR were never a subject in my life. I never wanted to live there; I hated this regime and the views of Ul-bricht. Only my dear mother Sarah was still happy in Levetzow Street, but the house was technically no longer to be saved, we thought at the time.

My father bought us an apartment in the district of Mitte, and we all went soon to the west of Berlin. He only picked up the last things from our old apartment and what was left in the cellar. As I learned shortly before his death, he seemed to have extracted far more from the basement than we could have known. The documents and photos he had saved at the time were good for a bestseller. But with me, my father knew the secret was in good hands when it ended with him.

Who knows, maybe in our family there will be another writer who takes up the subject. I promised my father I would not do it. Of course, I kept it to this day! Not just because I promised it to him—I don't believe it, or I do not want to believe it. Only my own story can tell it.

Young Luck (1945––1951)

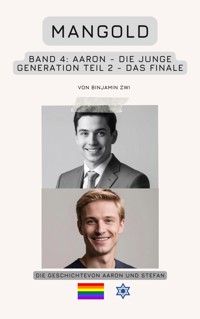

[ 02 SARAH, HANNAH, ARI ]

HANNAH EPSTEIN (CENTER) WITH MOTHER SARAH (LEFT) AND BROTHER ARI (RIGHT) BEFORE THE PERSECUTION, BERLIN CA. 1940

NEW LIFE AND THE MOVE

Since no one in Hans's family was alive, my dear father Yaron wanted Hans to stay with us even after his liberation. Not only had we become a family in the underground: My father already knew that we loved each other, and I also soon had my Bat-Mizwar; I became religious, and I was allowed to have a friend.

Then, we moved to our new apartment in the Mitte district in 1946. Hans came with us, as well as my older brothers Ari and Adam. Adam with his fiancée Rosa and their son Leon. Together, we got a 4-room apartment without a toilet, and there was neither electricity nor running water, but after all, we lived.

Father started as a housekeeper in the residential block, because he had shown his versatile talents in the war many times enough. The residential block was taken by the Russians at the time. But when the sectors were divided among the four occupying powers, we came to the British sector – fortunately! This residential block was one of the few residential blocks on this street that remained almost intact. Father enjoyed a good reputation among the occupiers thanks to his craftsmanship. Before the war, he had run a carpenter's workshop in Levetzow Street with a shop business. Eliam had told the new gentlemen enough about the deceptively real-looking twisted door in the old railway tunnel, without which we could not have survived so long.

My father did not want Hans to live in my room, but I knew how to wrap him around the finger. (My granddaughter Leah is the same today as I was back then. I think with a smile as I write this sentence down.)

In any case, Hans lived with me, and Adam and Rosa also shared a room. Ari wanted to live with Zuria, the wonderful shepherd. Of course, mom and dad also had a shared room. Then there was the kitchen and a living room, but there was nothing inside. What are chairs or a couch if you could also sit on boxes? (Yes, today you can laugh at it!)

My father took away our fate and admonished us to humility. He always said: “What are material values when you have yourself and live!” He was right! Yeah, he was often right, even though I didn't always understand him at the time.

We volunteered for reconstruction. We children were allowed to do easier work because school was not yet. Let no one say that we Jews are lazy! Quite often, we were kept pretending that we were to blame for all this. Hitler had seen this before, or at least he had claimed it. And they still liked to believe it.

My mother cried a lot, but she was a strong woman. She would have liked to work as a teacher again, but the country was on the ground, and no one thought about education in the first few months. But I was glad that we Jews were then allowed to go back to school from September 1946. Our occupants had ensured that our imperialist and militarist views were transformed into a democratic attitude in the school. It was no different in West Berlin than it was in the East.

It was good for us Jews. We could only win. The occupier saw us no differently than the other Germans. But the Aryan children refused to sit next to a Jew. Something like this was speaking around quickly in the class, especially since we were from Berlin. At least I was more fortunate than Ari. He had to sit alone in the back. I was allowed to sit next to Hans.

After school we had to go to reconstruction every day, knocking mortar from the bricks. The occupants wanted to reuse the bricks, and so many new living blocks for the population – it said. Often, however, the damaged buildings had to be renovated first. That's where the invaders moved in. We came to the end; And from this point of view, we were suddenly a single German people!

We met with our fellow sufferers from underground in temporarily furnished synagogues. During the long time together under the earth, many friendships had arisen. Some of them hold to this day. I often went to such at the time. were the friends I had.

There was always a lot to tell. We were all getting better from day to day, no matter how bad it was. Hans also occasionally came with me, but he had never been happy down there and did not want to be reminded of that time. He said, "The only good thing about my salvation was that I met you." That touched me deeply at the time.

My mother and father always liked to accompany me to meetings, because they had many friends there. She had a very good relationship with the Bundschuh family. After the war, Jakob Bundschuh managed to regain his banking house in the American sector. Adam was allowed to work in his bank because he and Eliam had saved the family Bundschuh.

(In the American occupation zone, the restitution procedure was regulated in the Military Act No. 59 of 10 October 1947, which was also introduced two years later for the British occupation area and Berlin, but not for the French occupation Zone. The law provided for the restitution of all identifiable deprived property, primarily commercial property and real estate, and assigned the individual cases to local reparation authorities, before which the two parties should agree on a settlement, if possible.)

Bundschuh reopened his bank as one of the first in Berlin but allowed only the Jewish population as a clientele. So, my family got a bank account. It was exciting at the time! Today it already has a child, furnished by grandma and grandpa.

Due to the war and the lack of Rabbis and synagogues, I was not able to celebrate my Bat-Mizwar until I was 15. However, I have been practicing for this event since I was 13. My mother told me faithfully what I had to do and what the others would do, but in reality, it was different. Rabbi Chajm, who himself had been in the shelter, performed my Bat-Mizwar in the synagogue on Joachimsthal Street, and I was happy that it was him.

It was one of the most beautiful parties I've ever had. I can still see my mother crying in front of me today when I sat on the chair and was pushed up. Apart from the many gifts, I got things that I have until now in my jewelry box. Mr. Bundschuh gave me a gold coin, which had been poured out in old Jerusalem. How he saved this gold coin through the war was a mystery to me, but he never revealed it.

Mother and father melted their wedding rings and made a goldsmith make a ring out of it. Inside, there was a message saying, <Mom and dad, always connected with you> Until I had always thought that father had given his gold ring to this brown bastard of a Wehrmacht soldier, who didn't want to leave him with us when we were driven out of our apartments in Levetzow Street. But he told me that the ring that this soldier got was worthless. Today, it is fashion jewelry or tin.

The greatest gift was that all our friends were there. Even Eliam came from Holland. He brought us a bunch of Gouda. Today it is nothing, but then it was like gold. The friends who didn't have much gave me homemade. I didn't want anything. I just wanted everyone to be there and be happy. I was never materially attached, on the contrary: I preferred giving rather than assuming!

Adam even brought wine. Supposedly, he was able to rescue a few bottles from the basement of the old cargo railway station in Moabit. I was not allowed to drink alcohol yet, but I accepted a bottle as a gift. This bottle still standing in the display case next to my desk today.

(Also, by the way, a drawing with all the persons who were near me in the shelter. A friend, a painter who had been there once had the idea of creating this painting. I won't inherit all these things that I'm thinking about to my son Samuel. He can't appreciate that. Aaron is the Mangold who has the same blood as me. He is benevolent, sensitive, and flattered by religious customs. I have so many things he'll get when I go on my last journey. But right now, I feel fit and don't think about my last trip.)

After my Bat-Mizwar I had to go to school for another year. I left with a good testimony, but what was it for me at the time? I wanted to study as a hairdresser, but no hair salon accepted me because I was a Jew, and there were no Jewish hairdressers in Berlin at the time.

I was sad, but I didn’t give up. I went to the housekeeping school – a new model to bring girls closer to the household. The Nazis had set up the first such school on Lake Wannsee. The occupants liked it and allowed this schooling. I learned a lot there, but it didn't make me happy. Hans always said that it's good if a woman can cook and clean. Men were real puppets at the time!

Hans had just learned that there were Note boards. You could put your data there. If someone from the family came and read the note, they could find you in this way. So, Hans also did this in his old street, waiting daily for a sign from someone from his family. So long time!

To our knowledge, his whole family was dead. But one day, a young man spoke with a Swiss accent. His name was Martin Hornmann, a lawyer from Zurich.

It was a knocking at our front door, and I still get gooseskin when I think of that moment.

I went to the door and opened it.

He said. “Good morning, lady!“

I said. "Good morning. Do you want to?"

"My name is Martin Hornmann. I am a lawyer, and I come from Switzerland. I got notice that Hans Mangold is supposed to live here."

"Yes, that's right. But what do you want from Hans? He is afraid of strangers."

"Oh, he doesn't have to. I am here to say something pleasant to him."

"Please come in. I will get Hans."

He politely said, “Thank you, dear lady!” and entered. I offered him a chair in the kitchen.

Then I went to Hans to pick him up: "Hans, there is a man who says his name is Hornmann, and he comes from Switzerland!"

"What does he want?"

"He says, he has got notice that you live here, and he has something good to tell you."

"Well, I'm coming."

Hans went with me to Mr. Hornmann, who was sitting in our kitchen.

"Mr. Mangold, I have been looking for you for a long time!"

"Good morning, what can I do for you?"

"Do you know a Samuel Mangold?"

"Yes! This was my father. He and the rest of my family were murdered in a massacre in 1944. But why do you ask?"

"Your father survived the massacre! He was able to flee to Switzerland."

"I can't believe it. Father lay dead next to me!"

“He was shot, seriously injured, and survived. My uncle rescued him and smuggled him to Zurich. I’ll give this to you!”

Hornmann gave Hans a passport; it was his own. His father had taken all the papers for security reasons at the time.

Hans started to cry. He couldn't calm down.

"Is my father still alive?" he asked with a crying voice.

"Yes, but he doesn't want to set foot on German soil! That's why he's sending me. I read in your old street that you live here."

"Hannah, my father lives!"

"Yes, incredible, almost seven years have passed!"

"Is there anyone else in my family alive?"

"Unfortunately, not!" said Mr. Hornmann sadly.

"My mother, my brothers, all dead?"

"Yes, but her death is not unpunished! I'm going to sue the Nazi regime in Nuremberg. Hundreds of us Jews have already done this!"

Hornmann suddenly felt anger. He was considered a warrior advocate. Well, in Switzerland, a Jew would like to become a lawyer, but especially in Nuremberg. Were the Jews a victorious power?

Hans didn't want to go on such a sluggish terrain. He preferred to stay with obvious family matters: "When can I see my father?"

"When you want! I can take you right away!"

That was too much! Hans had not even perceived that his father was still alive. Now he should even visit him! Hans had found a new life by my side here a long time ago. He slipped onto the kitchen chair and sat there sinking into himself for a moment.

He thought about it, he was ripped apart. But he could hardly wait to see his father again. So, he took a moment and explained to me in a serious voice: “Hannah, I’m going to my father, but I’ll catch you up!”

I didn't want to make a lift. I understood Hans. In our time, nothing was lasting. So, I reinforced his determination: "Go first to him, and someday we will see each other again."

At the time, I didn't think we'd ever see each other again. Hans was one of his own, and that's where he was going. It was a tough breakup, but it had to be. Hans had to bury his ghosts and arrange his life.

The day he and Mr. Hornmann left was the worst day for me since the end of the war. I had cried, and my family was trying to comfort me. Adam wanted to go to a romantic movie with me, but I couldn't.

I had to give up Hans for almost three long years. He did not forget me. I received letters from him – a great consolation – in the end, he kept his word.

I still have the letters. They're tied up in a bunch and lie in my vitrine next to my desk. I just took one out and quoted it here:

"Dearest Hannah, how much I miss you here in Basel! My heart hurts from longing for you. We haven't seen each other in so long! My father is fine. I only hear him at night. He calls for mom. Suddenly he is quiet. Tomorrow, we have an appointment with Martin Hornmann. It is about my father's company and my inheritance. I promise you. When I finally get back to you. I'll ask you if you want to be my wife. Be excited, dear Hannah! You and father are my only stops; I would give my life for you. I hope you answer my love. With a beautiful girl like you, it's hard not to think about it. Dear Hannah, I have to go to an appointment, but in my mind, you're always with me. I love you with all my heart. Your Hans"

I'm still melting today when I read what he wrote to me at the time.

On my 17th birthday in September 1949, it rang at our front door. (We've had electricity for almost a year.) I ran to the door and was scared as I opened it. A well-dressed young man in a black suit, a white shirt, and a striped vest stood before me and said to me. "Hello, dear, here I am!"

I jumped into his arms and knocked him off. Yeah, I didn't kiss him like a long time ago. "Hans, here you are! What do you look like?"

"I promised you in every letter that I would come back. My father would love to meet you. Can you come to Basel with me?"

"I would go anywhere with you, but we have to talk to father and mother first."

Hans frowned. I knew he had respect for my father. But then he asked me: “Are your parents there too?”

"Yes, today is my birthday! We have cake and coffee!"

"I knew that you do have your birthday today, my love. Happy birthday. Honey, this is for you!"

He gave me an elegant-looking box and a small drawer. Of course, I immediately opened the little drawer and yelled when I saw what was in that little fine box. It was a gold ring with a brilliant. However, I did not think too much about it. It was a ring for my birthday, I thought.

I pulled Hans by the hand towards the kitchen: "Come, Hans, my parents will rejoice!" And so, it was.

Hans seemed nervous. Then he began to speak with a slightly stumbling voice: "Before I have no more to speak, I will make it brief." Hans kneeled before me and said: "Hannah Epstein, do you want to be my wife?"

I shouted without waiting, "Yes, yes, I will!"

Everyone wished us good luck. Then Hans went to my father and picked up his blessing for the wedding. Dad loved giving it to us.

I said to my family. "I have something else to tell you. I'm going to Switzerland with Hans for a while. Hans' father wants to meet me. I hope you don't mind!"

At first, my parents still had doubts. I was not yet a major and wanted to go abroad. But I was able to change her mind. Then there was cake and “coffee vomit.” It was coffee laced with chicory and tasted like sleeping feet.

My father asked me. “When are you leaving, and why do you have to go to Switzerland?”

Hans replied. “Good morning, Yaron. We have to go to Switzerland because my father lives there and I work in his company. You know Hannah will do much better there. Above all, I can't leave my father alone. He has no one. You have your family, and they have you.

Father frowned. You could see that he was hurting, but he let me go. With Hans, I was well-raised after all, we loved each other and were engaged. So, it was the last afternoon with my beloved family for a long time. (I would stay in Switzerland longer than I thought.)

On my last night in Berlin, I slept very restless, was very excited, and had stomach pain. In the morning, Hans and I slept out. We had a long train ride ahead of us, over 14 hours from Berlin to Munich, where we would take the train to Basel.

We had to be at the station at ten to six in the evening. Hans wanted to make another appointment with Mr. Bundschuh. His father wanted to cooperate with his bank. I would have liked to go with him, but he said in a firm voice. "Dear, stay with your family and enjoy the day. I am just having boring conversations in a dusty old office."

I didn't say much about it at this time. After all, I was still a young girl. I enjoyed the last day with my father and mother. Later came Ari, Adam, and Rosa with my nephew Leon.

At four o'clock, Hans came back from his appointment and had to drink something first. I gave him some more cake and offered him coffee. That afternoon, I also opened the box that Hans gave me for my birthday. It was a beautiful dress: black, long-sleeved, and elegant (not a Jewish skirt). I would wear this dress on our trip and shine next to Hans.

Father and mother took us to the train station in Friedrichstrasse. We could walk; it was not far. From there went the long-distance train FD 150. We had to say goodbye on the platform edge. "Was it forever?" I wondered in secret.

Dad looked at me and shook his head. He wanted to hold me back, didn't he? No, he asked Hans: "How long will the train to Munich take?"

Hans drew out a timetable and looked. "From Berlin to Munich. We will take almost fifteen hours. We will surely have a longer border stay in Probstzella again.”

Father looked at us with uncertainty and continued: "Will Jews cross these borders without any problems?" I saw the fear in my father's eyes.

"Don't worry, Yaron. I have a passport and a visa for Hannah. They were issued for her by the Swiss Government. My father has many good contacts there.”

Mother looked at me and cried. Then she said quietly, "My child, take care of yourself. And you, Hans, take care of my daughter. May Adonai accompany you on your way."

"Mother, don't worry so much. Hans will take care of me."

"I will take care of your daughter, and we will call you by telegram."

My mother was more realistic. She knew this was not a fun trip. It was a life choice.

Father just hugged me. I saw the tears in his eyes. We got in and looked for our seats. Hans packed the suitcases in the luggage net, and I opened the window to wave to father and mother.

“Take care, I love you!” I called out to them again, and the train started moving. Mom and dad waved after me, and I watched them until I did not see them

"Oh, Hans. I am excited, what is in Basel? Are they better to the Jews there?”

He had hinted at it often enough in his letters, but I could not believe it. Maybe he just wanted to calm me down or deceive the censors.

“Basel is a wonderful city, and yes, they have nothing against us Jews there. Let yourself be surprised, my love!”

“I will, my dear!”

The first route was from Berlin to Munich. It was a pleasant route. The evening sun was shining, and I turned my face to the sun. I could feel the warmth, breathed on the pane, and drew figures with my finger on my breath. The most beautiful stories emerged before my eyes. (I have always been very imaginative).

Our first stop was Leipzig. The clock said quarter past nine in the evening.

“Look, Hans, how beautiful the train station is. And the huge hall, so much steel.”

Hans was thoughtful. Was he worried about the zone boundary? Nevertheless, he gave me an answer. “Yes, dear, it looks huge.”

Twenty minutes later, our train started moving again. The next stop was Saalfeld. The station was damaged during the war. Trains could still run. The only strange thing was that no one got in or out.

Hans told me our next stop was Probstzella. It was the border point. We would all have to get out there and walk to the zone border. I was afraid. Hans could see it and held my hand.

The train started moving again. I was shaking all over. When we arrived at quarter past one, you could hear the German Shepherds. The barking reminded me of our deportation back then. Tears welled up in my eyes. Hans noticed and took me in his arms.

"What is wrong with you, my love?" Hans protected me always and everywhere. (I knew that!)

“I am scared, and the howling of the German Shepherds reminds me of Berlin and the deportation.” (Since all of this, I have had a disturbed relationship with Moabit. Years later, we visited the Moabit freight station memorial and stood at the former platform 69. We both shed tears. Although Hans rarely cried. To this day, I cannot come to terms with it. No, I just cannot.)

Hans took his white handkerchief and wiped away my tears. “Do not be afraid. We have all the permits, and I am a Swiss citizen.”

The train stopped!

We had to get out with our luggage. On the platform were young Russian soldiers, not heavily armed, but with a dog. I was afraid of this. We had to pass by to get to the checkpoint. The young soldier in Soviet army uniform just stared at us. Fortunately, Hans knew where we were going. He had gone this way twice before.

When we arrived at the checkpoint, we had to stand in a queue and wait. Luckily, things happened quickly at this point. A little further ahead, I saw a young couple being dragged away. The girl was crying, and I tried to stay calm.

I managed to do this until it was our turn. In front of us stood three Soviet Army soldiers and two German police officers. The two police officers checked the passports and our luggage.

Luckily, we only had two suitcases with us. Nevertheless, the policeman asked, “Do you have any Eastern money with you?”

Hans said very calmly, “No, only Swiss francs. Not more than 300 francs.”

The police officer seemed bored, he looked at the passports, saw the necessary stamps from the outward journey, and also that of course I did not have one. Hans explained this to him using the documents he had from the Swiss government. The police officer took a closer look at them, and I inevitably thought of that young couple from before. When the policeman called a Russian officer, my heart sank.

Thank God the Russian officer spoke German, although somewhat broken, but good enough. He looked at the document and read it, looked at it again, looked at me, and asked me my name. I told him: “My name is Hannah Epstein." Immediately, I fell silent again.

He took my passport from the policeman, looked at my paper again, and then he said: "Okay, go!" The policeman let us through. I was relieved and happy that Hans had this document from the Swiss government!

(Years later, I learned from my father-in-law Samuel that it was a letter from the then Federal President Ernst Nobs. He was also head of the finance department and a good friend of Samuel. However, how much money he gave him for this favor remained secret. I still remember meeting him years later at a banquet.)

"Now, dear, we have to walk a few meters. Then comes the American border checkpoint, and once we get through there, we have made it."

I rolled my eyes and felt tired. But I had to persevere; I was tried and tested in that. After 200 meters and a curve, you saw the American border checkpoint. Again, we had to stand in line and wait. This time it happened quickly. It was our turn after just fifteen minutes. Three soldiers stood in front of us again, this time Americans. German police officers carried out the checks.

The policeman took a look at our luggage, looked at our passports and of course the document. (I was shocked, but the policeman smiled at me.) Then he wanted to know if we had Ostmark with us. We quickly said no, and he let us move on. I liked him. He looked nice and smiled. Although, I had to assume that his father had been one of our murderers.

Luckily the bus was already there. He would take us through the Loquitz valley to Ludwigsstadt. The driver took our luggage. We were able to get on, and the transfer was already included in the train ticket. (What a luxury!)

When the last passengers had boarded, we could get started. Our path led through the Loquitz Valley - a very beautiful place since the wall was opened. A few years before Hans' death, we allowed ourselves to have fun and walked this arduous path again.

Due to the steep mountain climb, the omnibus arrived 20 minutes late at the station, but we still had time. Our train did not leave until three past two. We were hungry, we were cold, and we were tired too.

"Dear, I am going to see if I can get something to eat. There must be a kiosk or something like that in the railway building."

It was in vain; Hans came back after five minutes. He looked furiously, and I froze.

"There is nothing there!" And Hans said with a crunch. “Come on, let us go inside the train and rest.”

On the train, we searched our compartment. When Hans saw a fat woman bite into a meat sausage in the third class, his mood did not improve. We ran through the train and arrived in our compartment. Hans put the suitcase in the baggage net and threw himself into his seat. I sat in front of him and looked at him.

I did this until he smiled and kissed me: "I love you, Hannah Adriana Epstein. I loved you then, I love you now, and I will love you till the end of my days."

I melted and was frightened when the train started moving. "Finally, we're leaving!" I relieved.

"That's right."

Hans took my hand and kissed her. He kissed my hand often and with pleasure. I looked out into the darkness and saw the lights of the houses passing through us.

(I found an old Timetable on the Internet. So, we stopped at three o'clock in Lichtenfels, at about half-four we were in Bamberg, at just before four in Erlangen, at a quarter to four in Fürth, ten minutes later in Nuremberg. Twenty minutes later it went on to Treuchtlingen. At ten past seven, we were in Augsburg, and after ten minutes we went on to the destination station. Man, there were many railway stations!)

We arrived in Munich at ten o'clock. There was nothing left of the former magnificent building and the large railway hall. A few months previously, halls and buildings had been blowed up. The railway continued operations at a temporary station.

At that time, the signs of the devastation inflicted by our liberators could still be seen everywhere in the city. The population was shrinking in reconstruction. If you see the result today, they have done a good work.

Our train left only in the afternoon. We could walk to the hotel in peace. A cab took us and our luggage to the Hotel Four Seasons, where we wanted to rest for a few hours. (It was called the House of Dollar Guests. Except for the occupants, only civilians who paid in hard currency were allowed to stay there. Hans paid in Swiss francs, and they are still 'hard' today.)

When we arrived at the hotel. We could not get out of our amazement. The building was not finished yet and had been severely destroyed in the war. Still, its splendor was undeniable. Only a part of the work could be done in certain areas, But the finished area was beautiful.

We checked in at the emergency reception. A lady wrote down our dates, a page brought us to the room. Of course, the furniture was new. The room was completely renovated and elegantly decorated. Unbelievable that in the war, this part of the Hotel was completely burned down. The page put our suitcases in the room, and Hans gave him a tip. I was very exhausted and had to sit down.

Hans, on the other hand, was restless and tense. First, he took off his jacket and hung it on the coat rack, then he went to the window and looked out. Suddenly Hans ran back to the cloakroom and took his Jacket.

"Dear, I'm going down to reception for a moment."

I couldn't answer as quickly as he was gone. What was he planning to do? A surprise? He always enjoyed making them for me very often. I wanted to freshen up and thought about whether I should put on a fresh dress too. Hans’ father certainly attached great importance to this sort of thing. Anyone who could obtain such important documents had to be very distinguished.

I went into the bathroom and freshened up. Hans came back and sat down in the armchair that was part of an elegant seating area.

When I came out of the bathroom I was wearing a black longsleeved dress. First, he looked at me, then he smiled and said. "Dear, I have a surprise for you."

I stood there and waited, but he had nothing in his hand.

”Dear, I thought we would stay overnight here in the hotel and not drive to Basel until tomorrow. We could take a look at the city, so much has already been rebuilt.”

“Yes, is that possible?” I clapped my hands together and was happy.

"Of course, that is possible! The hotel extended without any problems. After all, I pay with Swiss francs, and I've already checked the new train connection. We have to exchange the tickets at the train station.”

“How beautiful!” I exclaimed and was looking forward to exploring Munich.

Hans also went into the bathroom and freshened up. Later we wanted to go to the train station and then go for something to eat. We were starving, but we were still able to control ourselves. We were civilized Jews, after all. (Wink in eye)

When Hans came out of the bathroom, we were ready to go. We left our key at the reception and walked to the front of the hotel. Cabs were waiting there, and we decided to use one of them. A younger man offered to drive us. Hans agreed the journey could begin from Maximilianstrasse via Maximiliansplatz and Karlsplatz. The cab only had to make detours at the piles of rubble. But in the end, we happily reached the station square. We asked the coachman if he wanted to wait and show us Munich later. He agreed; Hans paid in advance.

We went to the makeshift station building and looked where we could buy tickets. It wasn't that easy, but a nice woman from Munich helped us. Rubble was also cleared away from the station square, and the lady in her fifties helped, as she said, to rebuild her city. (These rubble women later went down in history)

She walked with us around a corner to a makeshift sales room. There was a lot of activity. Hans went in alone I looked around. But I was careful not to be recognized as Jewish.

(The Protestant theologian Johann Jacob Schudt (1644–1722) from Frankfurt am Main devoted a chapter to our appearance in his Jewish Oddities (1714). In it, he wrote: "That one can immediately recognize a Jew among so many thousand people." G-d has endowed the Jews with unique "characters or characteristics" "that one soon sees them as Jews at first sight." Schudt particularly emphasizes the face, "that the Jew immediately stands out ... at the nose ... lips ... eyes also of color and the entire physical posture." Schudt sees the body as a medium of character and way of life (like his contemporaries), but the external appearance is determined by the social role (and not by the theological one, as his contemporaries saw). According to Schudt, Jews disrupt the divine order because of their appearance. What nonsense!).

I was standing at one of the few remaining lanterns, watching a group of older men drag a large iron girder down from a pile of rubble.

I heard. “Darling, are you dreaming?” Hans stood in front of me and looked at me with a smile.

"No, why should I? I just watched the men at work!”

"I was able to exchange the tickets. Our train leaves tomorrow morning at ten o'clock and goes via Freiburg to Basel."

"Okay, then we still have a lot of time. Let’s go to the cab. Our coachman has been waiting for a long time.”

Hans took me by the hand, and we walked together along the station square. When we got to the cab, the coachman took us on a little tour through the city.

It was not pretty because most of the sights he showed us were damaged or destroyed. I quickly lost the desire to see the rubble of the city.

I was hungry, and I'm sure Hans was too. I asked Hans to stop somewhere to get something to eat. That was harder than expected because there wasn't much, but the coachman knew something commoner. He drove us to the Hofbräuhaus. Like almost all other buildings, it was seriously damaged in the war. However, the Schwemme, the large beer hall, was largely undamaged and could continue to be used. There wasn't much going on at that time of day, and my dear Hans invited our coachman to dinner. (Hans was always so generous.)

We entered the large hall, and I was amazed: what a beautiful ceiling! The paintings were a feast for the eyes - motifs from different areas of life, such as agriculture or fishing, and Bavarian flags. I loved this blanket and kept looking at it, even as we sat. Worth mentioning are the wrought iron candlesticks that hung from the ceiling.

There wasn't much to eat. I was happy when there was soup. And yes, there was soup. To be more precise, it was potato and cabbage soup, and it tasted delicious. Hans and the coachman drank beer, and I got lemonade. We enjoyed our time at the Hofbräuhaus.

Hans paid, and the coachman drove us back to the hotel. We passed all the piles of rubble and people trying to move these monsters away. An older woman looked contemptuously in my face as if to say: “Get your ass down there and lend a hand!” Did I have to feel guilty? Certainly not, because weren't those who were now on the ground the ones who wanted it that way? Only they had just lost.

When we arrived, Hans paid the coachman, and we said goodbye. We picked up our key and went to our room. We made ourselves comfortable there. Hans went for a bath, and I read a book that I found on one of the shelves in the room. We went to sleep early. Hans wanted to get up early.

The following morning, Hans got up first and then me. Hans was coming out of the bathroom, so I was able to go straight in. I got ready, put on my black dress, and went to Hans.

When he saw me, he looked at me and asked, “Why are you wearing this dress?”

I said, "Because I want to make a good impression on your father."

“Do you think my father values something like that?”

“Someone as powerful as your father would certainly value it!”