Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

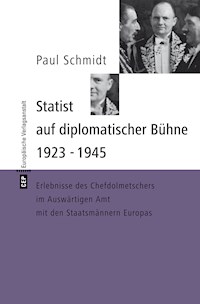

As an interpreter in the German Foreign Ministry, Paul-Otto Schmidt (1899–1970) was in attendance at some of the most decisive moments of twentieth-century history. Fluent in both English and French, he served as Hitler's translator during negotiations with Chamberlain, the British declaration of war and the surrender of France, as well as translating the Führer's infamous speeches for radio. Having gained favour with the Nazi Party – donning first the uniform of the SS then that of the Luftwaffe – Paul Schmidt was given 'absolute authority' in everything to do with foreign languages. He later presided over the interrogation of Canadian soldiers captured after the 1942 Dieppe Raid. Arrested in May 1945, Schmidt was freed by the Americans in 1948. In 1946 he testified at the Nuremberg Trials, where conversations with him were noted down by the psychiatrist Leon Goldensohn and later published. After the war he taught at the Sprachen und Dolmetscher Institut in Munich. Hitler's Interpreter presents a highly atmospheric account of the bizarre life led behind the scenes at the highest level of the Third Reich. Roger Moorhouse is a historian of the Third Reich. He is the author of the acclaimed Berlin at War, Killing Hitler and The Devil's Pact. He has contributed to He Was My Chief, I Was Hitler's Chauffeur, With Hitler to the End and Hitler's Last Witness.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 526

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Title

Foreword

Extracts from the Editor’s Preface, 1951 Edition

Introduction

ONE

1935

TWO

1936

THREE

1937

FOUR

1938

FIVE

January to 3 September 1939

SIX

3 September 1939 to End of 1940

SEVEN

1941

EIGHT

1942 and 1943

NINE

1944 and 1945

EPILOGUE

1945 to 1949

Plates

Copyright

FOREWORD

When Paul Schmidt was training as an interpreter in the German foreign office in Berlin in the early 1920s, he would scarcely have imagined the role that he would one day play in some of the most central events of the twentieth century. Schmidt, a Berliner and a veteran from the First World War, studied modern languages in the early 1920s in Berlin. He briefly moonlighted as a journalist before enrolling in 1921 on the training course that would change his life. He was evidently a brilliant student, proficient in French, English, Dutch, Spanish, Russian, Czech, Polish, Slovak and Romanian, and able – by his own account – to commit as much as twenty minutes of speech to memory before giving his translation.

Interpreting was quite a new field and was the result of a paradigm shift in diplomacy in the aftermath of the First World War. Before 1914, French had served as the lingua franca of international dialogue, with every diplomat expected to be proficient in the language. However, after 1918, the rejection of the perceived ‘secret’ methods of diplomacy meant that the old Francophone norms had to be abandoned. Suddenly, the need arose for a trained cadre of professional interpreters to aid communication in the international arena; Schmidt would be one of the most famous examples.

Employed in the German foreign ministry from 1923, Schmidt already had over a decade of experience before he first interpreted for Hitler in 1935. It was the start of a relationship that would propel him to the very heart of the story of the Third Reich and of the Second World War.

Paul Schmidt’s memoir is a remarkable account of a remarkable career. He was simply everywhere. He acted as interpreter in discussions between Hitler and Mussolini, with the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, with British Foreign Minister Lord Halifax, with Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, and with Lloyd George. He was called on to interpret at the Nuremberg Rallies, at the 1936 Olympics, in the Reich Chancellery in Berlin and at Hitler’s residence in Berchtesgaden. He interpreted at the Munich Conference in 1938, travelled to Moscow for the negotiations that led to the infamous Nazi-Soviet Pact in 1939, and accompanied Hitler to Hendaye to meet Generalissimo Franco in 1940. Even when he was not directly interpreting, Schmidt was usually present within the entourage to make detailed records of conversations for the German foreign office.

Later in the war, in 1942, he was brought in to interrogate Canadian prisoners captured in the Dieppe Raid. He even interpreted for the Allies in the preparation of the Nuremberg tribunal.

As a result of his apparent ubiquity, Schmidt’s recollections are of tremendous value both to those interested in pre-war and wartime diplomacy, and those interested in the inner workings of the Nazi state. Though he was intimately involved in many of the discussions that he describes, there is nonetheless a curious ‘fly on the wall’ quality to his memoir. He comes across as detached and objective, dryly observing events and the individuals concerned.

That detachment and objectivity, Schmidt suggests, is an essential part of the interpreter’s art. The greatest mistake an interpreter can make, he says, is to assume that he or she is ‘the leading actor on the stage’. Instead, he claims that the primary quality of a good interpreter, paradoxically, is the ability to remain silent.

Of course, Schmidt is less than entirely silent about his former employers. About Hitler, for instance, he was sometimes complimentary, impressed by his master’s clear and skilful mode of expression. Hitler was, he said, ‘a man who advanced his arguments intelligently and skilfully, observing all the conventions of such political discussions, as though he had done nothing else for years.’

On other occasions, however, he spied what he described as ‘the other Hitler’, brooding, distracted and non-committal. Utilising the racist vocabulary of the age, Schmidt even saw fit to question Hitler’s genealogy, criticising his ‘untidy Bohemian appearance’, his ‘coarse nose’ and ‘undistinguished mouth’ – all of which led him to believe that Hitler might be the product of some ‘miscegenation from the Austro-Hungarian Empire’.

Others fare little better. Goebbels is described, pithily, as ‘a wolf in exceptionally well-tailored sheep’s clothing’; Ribbentrop was arrogant, vain and suspicious in equal measure. Only Göring emerges from Schmidt’s account with even a modicum of praise.

He could be similarly candid in describing other salient figures. Franco, for instance, was so short, stout and dark skinned that ‘he might be taken for an Arab’. About Mussolini, he was relatively positive, praising the Italian Duce’s laugh – ‘free and whole-hearted’ – and his speaking style: ‘he never said a word too many, and everything he uttered could have been sent straight to the printers.’

Schmidt was himself no Nazi; rather he was an old-fashioned, conservative nationalist. He was given an SS rank in 1940 and joined the Nazi Party in 1943 but these were more formalities than acts of ideological commitment, and he was duly exonerated by the denazification court after 1945. As this memoir demonstrates, Schmidt tended to view his Nazi masters with the haughty disdain that is typical of a senior civil servant. They were simply beneath him. He described them, rightly, as ‘fanatics’ and ‘enemies of mankind’; his friends and colleagues at the German Foreign Office viewed them, he claims, as a ‘transitory phenomenon’ – and yet he served them loyally for over a decade.

Indeed, what might surprise readers is that – apart from that aside – Schmidt is strangely uncritical of his former masters and is seemingly unrepentant about the work that he did for them. Of course, as interpreter, he had no hand in formulating policy, and was restricted solely to facilitating communications between parties, at which – evidently – he was an expert.

But it is nonetheless disconcerting how Schmidt appears to render the Third Reich almost completely harmless. He makes no mention of the Holocaust, for instance, despite the fact that when this book was first published in 1951 knowledge of the Nazis’ genocide against the Jews was already well advanced and was being widely discussed. Surely it would have merited a mention, if only to state – perhaps mendaciously – that he had known nothing of it?

Schmidt had the opportunity, with the publication of this memoir, to wipe the slate clean; to set some distance between himself and his former masters. But, he said nothing, and recalled his time serving Hitler with only the aloof hauteur of the inveterate snob. Hitler’s greatest crime, one might conclude from Schmidt’s account, was to have neglected to pass the port.

So it is that Schmidt references the fall of the Third Reich in 1945 with only the laconic comment, ‘thus ended my work as an interpreter.’ There is no evident remorse for his ‘not unimportant role’ in wartime diplomacy, just the dry, rather amoral detachment of the bureaucrat blindly following his instructions. This, I think, is instructive.

Schmidt comes across as urbane, cultured and thoughtful; he seems to belong to a very different class from most of the other members of Hitler’s entourage. The Führer’s drivers, valets, cooks and secretaries were, on the whole, rather uncomplicated individuals who had not enjoyed the benefits of a university education or a more cosmopolitan, liberal world view. Schmidt was different. He had studied at Berlin’s prestigious Humboldt University; he had been awarded a doctorate; he spoke numerous foreign languages. Yet, for all those differences, Schmidt shared one essential trait with his less advantaged fellows; what one might call ‘moral myopia’. Like the valets and the secretaries – most of whom adored Hitler as an avuncular ‘boss’ and a man of perfect Viennese manners – Schmidt was unable to see beyond his immediate environment, unable to recognise the moral squalor of the Nazi Reich and unable to discern the hideous, misanthropic character of the endeavour in which he played his ‘not unimportant role’.

The primary difference between Paul Schmidt and his fellows, therefore, is that – like so many educated Germans of his generation – he really could, and should, have known better.

Roger Moorhouse

2016

EXTRACTS FROM THE EDITOR’S PREFACE, 1951 EDITION

Although we think inevitably of Paul Schmidt as ‘Hitler’s Interpreter’, he had in fact been interpreting for a whole series of German Chancellors and Foreign Ministers during the decade before Hitler and Ribbentrop entered the international scene.

The first half of the German edition of Dr Schmidt’s book is devoted to his reminiscences of that earlier period. I decided, in preparing a book of reasonable size and closely sustained interest for the ordinary British reader, to leave out the pre-Hitlerian part altogether.

Schmidt is at pains to make it clear that he places the Nazis – especially Hitler and Ribbentrop – in the category of ‘fanatics, the real enemies of mankind, in whatever camp they may be’. He is damning and often contemptuous in his judgments of the men for whom he worked so loyally for so long – and has been criticised on that account. He claims that he was never a Nazi sympathiser, that he merely did his job as a civil servant and expert technician, that he made no secret of his independent outlook and that this was duly noted against him in his dossier.

His account of himself seems to be borne out by the impression he made, among others, on Sir Neville Henderson, British Ambassador in Berlin until the outbreak of war. He certainly showed considerable courage of a negative kind in that, despite his very special position, he resisted pressure to join the Nazi Party until 1943. On the other hand he makes no concession to the view that the German people as a whole were in any way responsible for Hitler. He attributes the triumph of the nationalist extremists in Germany to the economic crisis of 1930–32 and to what he described as the mistakes on the part of the Allies in making their concessions to Germany too late and too grudgingly. I think Schmidt might fairly be described as an enlightened, cosmopolitanised German nationalist, and find it a little hard on him that we have to hand him down to posterity as ‘Hitler’s Interpreter’ and not, perhaps more aptly, as ‘Stresemann’s Interpreter’ – a title to which he has at least an equal claim.

R.H.C. Steed

1951

INTRODUCTION

‘Archduke Franz Ferdinand Assassinated at Sarajevo!’ With these words I became acquainted for the first time with current affairs when the Special Editions appeared on the streets of Berlin in June 1914. I was still at school then, knew nothing about politics and in my history classes had not yet studied beyond Karl V. Therefore at that moment in time I did not have the slightest presentiment of the event’s significance and how it would mark the turning point not only of my own life, but also the future history of Germany, Europe and the whole world.

‘First mobilisation second of August!’ the village crier informed the farming families of the small Mark Brandenburg town where I was staying with relatives, thereby announcing officially the outbreak of the First World War. Shortly afterwards, as a 15-year-old auxiliary policeman, I wore a white armband, carried an unloaded rifle on my shoulder and played at ‘railway protection’ below a railway bridge. In 1915 I helped usher in the ‘age of food rationing’ as later historians were to call it, when I distributed ration books. In 1916, I studied for my school-leaving certificate while working at a munitions factory known as BAMAG (Berlin-Anhaltischer Maschinenbau A.G.) in the Huttenstrasse.

In 1917 I was called up. By then Berlin had already experienced its first food riots. Beneath the surface there was growing unrest amongst the masses: we Berlin recruits were therefore sent for training to the farthest possible regions of the Reich. So I came to the Black Forest and was provided with my basic training on the Hornisgrinde and at the Mummelsee as a mountain infantryman together with others from Berlin, most of whom had never seen a hill higher than the Berlin Kreuzberg in their lives.

One day, we were issued with field-grey uniforms to replace the old blue ones so that we looked like ‘real’ soldiers if one didn’t look too closely at our schoolboy faces. We were trained … in street fighting! We learnt how to force back masses of people energetically but without violence using the rifle at an angle, how to prevent a Socialist grabbing it, how to blockade streets and protect businesses. It was a strange beginning to a ‘heroic career’. We were used operationally in Mannheim, blockading streets against the hungry masses in revolt. There were no incidents. The Mannheim workers teased us mainly for our youthful appearance, but at the insistence of our officers made their way quietly home so that we forgot very quickly our ‘local police’ training tactics.

A few days later we were sent off to the real war just in time to take part in the great offensives of the spring of 1918. As a machine gunner I fought mainly in the ‘first wave’, as it was called, against the French, British, Americans and Portuguese, who bore the brunt of the March 1918 offensive defending a position the Allies had thought would remain quiet.

On 15 July 1918 I experienced for the first time a turning point in history. It was the first link in the chain of those historical events, beginning with me as a private soldier manning a machine gun, which would continue link by link to my close involvement with political leaders in my later career at the Foreign Office. That day Foch’s counter-offensive began, which would seal the fate of the German armies in the First World War.

As the German offensive proceeded, my company was in the first wave scattered behind the curtain of artillery fire and making its way through the cratered land at Reims. Suddenly we noticed the eerie silence and quiet withdrawal by the French. We had the distinct feeling that we were making a stab in the dark. The riddle was solved within a few hours when Foch, with his reserve army, embarked on a well-thought-through surprise counter-attack that threw us into total confusion at this most critical moment of our advance.

That morning as I sat in the shell craters at Reims I knew nothing of the decisive extent of the moment. I could never have dreamed that afterwards I would be closely involved time and again in the varied fates of Germany and Europe, that as future years passed I would witness at first hand, on the diplomatic and political battlefronts, the gradual resurrection of Germany to the height of its greatest power and then watch the wheel of history turn full circle. Almost a quarter of a century later, it would be at Reims that the unconditional surrender of the Third Reich became fact.

As a supernumerary private soldier I could never have thought it possible then that in 1936 at Obersalzberg I would have an in-depth talk with the British Prime Minister of the First World War, Lloyd George, and relate to him my experiences at the front. Even less so that twenty-two years later, in the historic dining car in the woods at Compiègne where the 1918 armistice was signed, I would sit opposite the French delegation as they signed another armistice. I knew nothing then of Locarno and the League of Nations; of the conversations between Briand and Stresemann; of the optimistic efforts to achieve peace in Europe in which I was involved in the 1920s as an interpreter; of reparations and conferences on the world economy; of Brüning and MacDonald; of Hitler and Chamberlain. At Reims in 1918 I was just happy that we had narrowly escaped the advancing Allies and embarked upon an orderly retreat. Later, positioned at a listening post in the American lines by night for my knowledge of English, I was wounded during the Argonnes offensive.

I came to Berlin during the chaos of the German Revolution. Wounded and walking with a crutch, I witnessed the Spartacus Uprising in the Friedrichstrasse and saw the front line that ran through the centre of Berlin and later divided the communist East from the anti-communist West.

As a Frontschwein I had been wounded and awarded the Iron Cross. In my future study of languages this gave me many advantages. I came into close and friendly contact with many British and Americans during the hyperinflation, worked as a student for an American newspaper agency in Berlin and as a result got to know international politics in the very intensive way that the Americans practised it.

After the Genoa Conference of 1921, the German Foreign office introduced special courses to train conference interpreters. It was without precedent because in earlier times diplomatic exchanges had mostly been handled by career diplomats, who all spoke French as a matter of course. French had been the common language of diplomacy before the First World War. After 1918 these circumstances underwent a major change. ‘Secret diplomacy’, considered to have been the principal cause of the war, would have to cease. There were now fewer diplomatic meetings and more great international conferences. Individual nations were no longer represented mainly by ambassadors but by statesmen – even the Prime Minister or Minister-President and the Foreign Minister – because it was believed that direct, personal contact would lead quicker to the achievement of goals than the old methods. These new representatives of nations were rarely competent in a language other than their own and thus a completely new calling came into being.

The interpreter who translated the speeches and conversations at such conferences owed his role in international politics to this democratisation of the methods of political negotiation. As of necessity he took part in the most secret discussions between two people, which of course entailed himself as the third. It was expected of him that if possible he would neither intrude nor undermine the atmosphere of confidence or the flow of discourse by too frequent interruptions to translate. This led to the new technique of conveying whole speeches or large extracts of conversation in a single delivery. In this way the interpreter as a disturbance faded into the background. Naturally it lengthened the time necessary to develop the negotiations, but on the other hand it gave his work the advantage that during his delivery the negotiating partners could formulate their questions and answers in a relaxed manner.

This new technique obviously required that the translator made memory notes while listening to the talk he had to translate. These notes were a major aid to the preparation of a reliable precis of the content. From them today the course of a negotiation can be reconstructed very accurately and they are therefore valuable materials for the historian engaged in research into the background and connections of the confused times after 1918.

The German Foreign Office courses taught this new technique with great thoroughness. Those participating were selected from amongst the students at Berlin University. Some were studying law, others languages. I received an offer to join and completed the entire course.

Meanwhile I had concluded my studies and in July 1923 was making my last feverish preparations for the oral exam. One evening, with an anxious eye on the approaching Romance test, poring over a huge tome on the troubadours of old Provence, fate came knocking in the truest sense of the word. A messenger from the Foreign Office arrived bearing an express letter from the head of the Languages Division instructing me to attend a small restaurant on the Savigny Platz in Charlottenburg that same evening for a conversation with him.

Over a glass of wine, my later chief of office, Privy Councillor Gautier, disclosed, to my boundless surprise, that difficulties had arisen with the interpreter at the International Court in The Hague and that it was his intention to substitute me on an experimental basis. ‘If you do well,’ he concluded, ‘maybe you can be transferred into the Foreign Office in the not too distant future.’

The ground seemed to tremble beneath my feet, and this was not due to the wine with which the all-powerful departmental head of the Foreign Office Languages Section had provided me to cushion the shock. After all, I had been simply tossed into an undertaking that to me looked like some crazy adventure. I would have to leave next evening, postpone my examinations and appease my course lecturers who would obviously view with great disfavour such an activity in the despised practice by a young student.

I made the decision to accept the offer and next evening, equipped with passports, visas, Dutch guilders and a ticket for a couchette, sat waiting at the Friedrichstrasse station. It was the first time in my life that I had ever got into a sleeper coach, and as I lay in the beautiful Mitropa bed it all seemed like a dream. Had I known then the journey that I was beginning, I would scarcely have slept a wink. Had I been able to foresee how many thousands of kilometres I would journey across Europe over subsequent years, how often in due course ever larger and more comfortable aircraft would fly me between Berlin, London, Paris and Rome, so that even today I could show a pilot the route, I would still have been wide awake as the train drew into The Hague.

As the train rolled out towards the Netherlands and my unsuspected destiny, world affairs ceased to be a private matter for me. From that evening on they would be part of my life.

Upon my arrival in The Hague on the Saturday, at the hotel I was approached by the outgoing chief interpreter for the Reich government Georg Michaelis. He had won his spurs at the Versailles peace conference after his predecessor had broken down when he saw the conditions being imposed on Germany and could not continue. Michaelis had seized his opportunity and impressed even Clemenceau and Lloyd George. President Wilson had declared that Michaelis must have been born and bred in Chicago, his American English was so good. Michaelis was a language genius. He was the master of eleven of them, and not ‘on crutches’ with the aid of dictionaries and grammars as is the case with many, but fluently, as though each language were his mother tongue. I can confirm that personally, having heard his English, French, Spanish and Italian, and the Dutch told me that his Amsterdam accent was faultless. Michaelis had the allure of a world-famous star and that was his downfall, for an interpreter is not the leading actor on the stage as he often seemed to assume. He is at the centre of an event and speaks for the greats but must remain mindful of the fact that he is only a small cog in the great clockwork of international affairs. His failure to remember this latter rule caused him constant problems with the German delegations, and in this case finally with the former Justice Minister, Schiffer.

‘Can you take shorthand? Have you ever acted as an interpreter before anywhere?’ When I answered no to all his questions, Michaelis forecast that it would not be possible for me to handle the complicated legal material before the court and my ship would definitely founder. With that he took his leave.

I had one day’s grace to acquaint myself with the material before the court, which would reconvene on the Monday. Knowledge of the subject matter is actually an indispensable precondition for the interpreter. Over the years I have become ever more convinced by my experiences that a good diplomatic interpreter must have three qualities in this order: first, and paradoxical though it may seem, he must be able to keep silent; secondly, he must be expert to a certain extent in the matters he will have to translate, and thirdly, strange to say, comes command of the language. The best translating ability will not avail the interpreter who does not know the subject. A bilingual layman will never be able to put over what a professor of chemistry is explaining, but a chemistry student with reasonable language skill will be able to make himself understood to a foreign chemist. For this reason, when I reported to the delegation heads I boned up on the subject and then went off with the files to read in peace.

The case was later to become famous in international law. The British steamer Wimbledon had been chartered by a French concern to transport artillery and other war materiel from Salonica to the Polish naval depot at Danzig. The German authorities had refused to allow the ship to transit the Kiel Canal on the grounds that Poland and the Soviet Union were at war, and that Germany as a neutral was obliged under the conventions of neutrality to refuse passage of war materiel destined for either belligerent through German territory. On 23 March 1923, a few days after the incident, the French Ambassador in Berlin had called upon the German government to lift the ban on passage by virtue of Article 380 of the Treaty of Versailles, which stated that ‘the Kiel Canal must remain open for passage to the warships and merchant ships of all nations at peace with Germany’. The German Reich contended that the obligations of neutrality under international law overrode the provisions of individual treaties, especially since Soviet Russia was not a signatory to the Versailles treaty.

This relatively simple but highly significant case for the times had now been garbed in a mass of complicated legal argument, but at least I had grasped the main points. On the Monday the court and public galleries were packed. The session began when Justice Minister Schiffer delivered his thirty-minute long statement from the witness box. I scribbled my notes in great haste as I had been taught on the Foreign Office courses and had practised hundreds of times. I filled page after page in large capitals and also added where appropriate important figures of speech and meaningful subordinate clauses. When Schiffer stepped down the President of the Court said, ‘Translation.’

Because French and English were the working languages in the court, Schiffer’s original pleading in German had no official value and was not even taken down by a shorthand writer. What the court would accept in evidence was my translation into French of what Schiffer had said in German.

I gathered up my notes and went into the witness box. Total silence had fallen except for some coughs and rustling from the public galleries. The judges looked at me expectantly. I took a deep breath and began. Suddenly all my tensions and anxieties fell away. Noticing after the first few minutes that the German pleading was not as difficult to put over as I had thought it would be, I began to feel almost at home in the witness box. One had to render the delivery to the President of the Court directly and my translation developed almost into personal advocacy to him. After half an hour I returned satisfied and relieved to my seat. Equally relieved was our small delegation. I was given to understand that its two head delegates, Schiffer and Martius, were very pleased with me.

What gave me pleasure was the courtesy with which we Germans were treated not only in court but also in the breaks outside it, when British, French, Italians and other Allied personalities conversed with us in the friendliest manner as though there were no Wimbledon case nor international tensions.

So I had come through my baptism of fire. Michaelis had gone with the remark that he could not understand how I had done it. On 17 August 1923, by a majority verdict, it was ruled that the German Reich had acted illegally in preventing the passage of the Wimbledon through the Kiel Canal and a fine of 140,000 francs was imposed.

After returning from The Hague, I sat my oral examinations at Berlin University. I received my doctorate on 1 August 1923 and was then recruited into the Languages Division of the German Foreign Office.

ONE

1935

The first time I interpreted for Hitler was on 25 March 1935, when Sir John Simon and Mr Anthony Eden came to the Reich Chancellery in Berlin for a round-table conference on the European crisis caused by German rearmament. Simon was then Foreign Secretary and Eden Lord Privy Seal. Also present were von Neurath, German Foreign Minister, and Ribbentrop, at that time special commissioner for disarmament questions.

I was surprised when I received the order to attend. It was true that I was chief interpreter at the German Foreign Office and had worked for practically every German Chancellor and Foreign Minister in the ten years up to the advent of the Hitler government in 1933. Then things had changed. Germany had dropped out of the small, man-to-man international discussions and had adopted the method of notes, memoranda and public pronouncements.

Furthermore, Hitler disliked the German Foreign Office and everyone connected with it. In the previous conversations between him and foreigners, the interpreting had been done by co-opting Ribbentrop, Baldur von Schirach or some other National Socialist as interpreter. Our Foreign Office officials were horrified when they heard that Hitler would not even allow State Secretary von Bülow to be present at these highly important discussions with Simon and Eden. In an attempt to ensure that at least one member of the Foreign Office should attend in addition to von Neurath, they decided to put me forward as interpreter. On being told that I had done good work at Geneva for a long time, Hitler remarked, ‘If he was at Geneva he’s bound to be no good – but so far as I’m concerned we can give him a trial.’ I was told this many years later by the English girl Unity Mitford, a supporter of the British Union of Fascists leader Sir Oswald Mosley, her brother-in-law. She was often invited as a guest of Hitler and overheard this remark by chance in assessment of my probable abilities.

The developments leading up to this Anglo-German meeting had been just as unexpected as the conference itself. Both France and Great Britain had been watching developments in Germany with growing concern. The British government was becoming alarmed at German rearmament, particularly the growth of the Luftwaffe. ‘Britain’s frontier lies on the Rhine,’ Baldwin had told the House of Commons in July 1934, and in November he had pointed openly to German rearmament as the most important factor for general unease.

While the French adhered to her established policy of a comprehensive system of security pacts to protect herself against Germany, the British had decided to seek clarification of the German intentions through talks. This idea was expressed in a joint Anglo-French communiqué of 3 February 1935: ‘Great Britain and France are agreed that nothing would contribute more to the restoration of confidence and the prospects for peace between the nations than a general settlement freely concluded between Germany and the other Powers.’

In mid February the German answer was given in a note I was required to translate into French and English and whose peaceful tone surprised me: ‘The German government welcomes the spirit of friendly discussions between the individual governments expressed in the communications from HM government and the French government. It would therefore be very acceptable … if HM government … was prepared to enter into an immediate exchange of views with the German government.’

With surprising alacrity and readiness, the British government offered to send Foreign Minister Sir John Simon to Berlin at the beginning of March. Then an unexpected development intervened. Shortly before Simon’s scheduled visit, the British government issued a White Paper intended to justify its own rearmament to Parliament:

Germany is not only rearming openly and on a large scale contrary to the provisions of the Treaty of Versailles, but has also given notice of withdrawal from the League of Nations and the disarmament conference … HM Government has obviously not declared itself to be in agreement with the breach of the Treaty of Versailles … German rearmament, if continuing uncontrolled at its present rate, will reinforce the concerns of Germany’s neighbours and could endanger peace … Moreover the spirit in the which the people and especially the youth of Germany is being organised justifies the feeling of unease which has indisputably arisen.

The National Socialist press was indignant, and Sir John Simon’s visit was postponed on the grounds that Hitler had a cold. Within the Foreign Office it was being said that it was not a diplomatic lie, Hitler really was verschnupft, a word that means both to have a cold and to be in a huff.

Events now followed one another apace. On 6 March the French government introduced two years’ national service; on 7 March the Franco-Belgian military agreement of 1921 was extended. On 16 March Hitler replied by reintroducing conscription. Military parity, permitted to Germany in December 1932 by negotiated agreement ‘in a system of security for all nations’, had become reality by a unilateral decision of the Reich ‘outside a system of security’. My friends in the Foreign Office commented that this could have been achieved more quickly and cheaply by negotiation, as in the evacuation of the Rhineland and in the case of reparations. In the light of my experience of the way in which Stresemann and Brüning conducted negotiations, I thought that the methods of the latter pair would have obtained the objective faster had it not been for the adverse developments before and after 1933. That it would have been cheaper for Germany and the whole world is known only too well today.

Two days later, on 18 March, HM Government protested ‘… against the introduction of conscription and increasing the standing peacetime Army to 36 divisions. After the setting up of the German Luftwaffe, the declaration of 16 March is a further example of unilateral proceedings … which, quite apart from the issue of principle, are seriously increasing unrest in Europe.’ To our astonishment the note concluded: ‘HM Government wishes to be assured that the Reich Government still wishes the visit (of Simons) to take place within the terms of reference previously agreed.’ This last sentence came as a surprise to us translators, for we had never imagined that the British would finish off a diplomatic protest with a polite enquiry whether, despite all the foregoing, they were still welcome to come to Berlin.

‘As far as I am concerned,’ François-Poncet, then French Ambassador in Berlin, wrote in his memoirs, ‘I suggested immediately after 16 March that the powers should recall their ambassadors forthwith and set up a common defensive front against Germany by speedily concluding the Eastern and Danubian Pacts. Great Britain should naturally make it quite clear that in the future any negotiations would be superfluous, and that Sir John Simon had finally abandoned his plan to visit Berlin. My suggestion was regarded as too radical and therefore not considered.’

It was not until 21 March that M. François-Poncet handed us the French protest, which I translated for Hitler as follows:

These decisions [conscription, standing army of 36 divisions, creation of the Luftwaffe] clearly conflict with Germany’s obligations under the treaties she has signed. They also conflict with the statement of 11 December 1932 [Military parity within a security system] … The Reich Government has deliberately breached the fundamental principles of international law … The Government of the French Republic considers it to be its duty to deliver the most emphatic protest and to take all necessary precautions for the future.

Half an hour later our future Axis allies, the Italians, entered the fray. In his note, which we had to translate very quickly, the Italian Ambassador spoke only of taking ‘unrestricted precautions’, and in his final sentence stated that the Italian government could accept no fait accompli resulting from a ‘unilateral decision annulling international obligations.’

A mere comparison of the texts of these three notes showed me that the isolation of Germany had begun to loosen. Cracks were apparent in the united front. It was with this thought in mind after the dramatic to-and-fro of the previous week that I sat, two days later on the morning of 25 March, between Hitler and Simon as interpreter in the Reich Chancellery.

Hitler welcomed von Neurath and myself quite pleasantly that morning in his office, in the extension that had been completed under Brüning. It was the first time I ever saw Hitler in person. I had never attended any of his public meetings. I was surprised to find that he was only of medium height – photographs and newsreels always made him appear tall.

Then Sir John Simon and Anthony Eden were shown in. There were friendly smiles and handshakes all round despite the very recent protests and the warning that ‘unilateral action had seriously aggravated anxiety abroad’. Hitler’s smile was especially friendly – for the very good reason that the presence of the British guests was a triumph for him.

‘I had the military sovereignty of the Reich restored a few days ago,’ Hitler began, ‘because the Reich is under great threat from all sides. The danger lies principally in the East.’ There followed an indictment of Bolshevism lasting about thirty minutes. In contrast to his public utterances on the subject – especially in radio broadcasts when his voice would tend to be as harsh as that of a market crier, his words issuing from the loudspeakers in a distorted form – he did not get himself particularly worked up in the presence of the British. All the same, from time to time he did speak more emotionally: ‘I believe that National Socialism has saved Germany, and thereby perhaps all Europe, from the most terrible catastrophe of all times … We have experienced Bolshevism in our own country … We are only safe against the Bolshevists if we have armaments that they respect.’ He spoke occasionally with some passion, but never went beyond the limits of what I had heard in the more excited moments of other international discussions.

His phraseology was perfectly conventional. He expressed himself clearly and skilfully, was clearly very sure of his arguments, easily understood, and not difficult to translate into English. He appeared to have everything he wanted to say very clear in his mind. On the table before him lay a fresh writing block, which remained unused throughout the negotiations. He had no notes with him.

I watched him closely when from time to time he paused to think over what he was about to say, which gave me an opportunity to look up from my notebook. He had clear blue eyes, which gazed penetratingly at the person to whom he was speaking. As the discussion proceeded, he addressed his remarks increasingly to me – while interpreting I have often noticed this tendency in a speaker to turn instinctively to the man who understands exactly what he is saying. In the case of Hitler, I felt that although he looked at me, he did not see me. His mind was busy with his own thoughts and he was unaware of his surroundings.

When he spoke about a matter of special importance his face became very expressive; his nostrils quivered as he described the dangers of Bolshevism for Europe. He emphasised his words with jerky, energetic gestures of his right hand, sometimes clenching his fist.

He was certainly not the raging demagogue I had half expected from hearing him on the radio, from his ruthless measures or his supporters in brown shirts and riding breeches ‘in action’ on the streets of Berlin. That morning, and during all these conversations with the British, he impressed me as a man who advanced his arguments intelligently and skilfully, observing all the conventions of such political discussions, as though he had done nothing else for years. The only unusual thing about him was the length at which he spoke. During the whole morning session he was practically the only speaker, Simon and Eden only occasionally interjecting a remark or asking a question. Hitler seemed able to divine when their interest was flagging – after all, they did not understand much of what he was saying – and he would then, at intervals of fifteen or twenty minutes, call on me to translate.

Simon looked at Hitler with by no means unsympathetic interest as he listened to him. His face had a certain paternally benevolent look about it. I had noticed it in Geneva when I heard him stating his country’s views in his well-modulated voice with all the clarity of an English jurist, though perhaps with too much emphasis on the purely formal aspects. Watching him now, as he listened attentively to Hitler, I had the feeling that his expression of fatherly understanding was deepening. Perhaps he was pleasantly surprised to find, instead of the wild Nazi of British propaganda, a man who was emotional and emphatic but not unreasonable or ill-natured. In later years, when foreign visitors spoke to me almost with enthusiasm of the impression Hitler made on them, I often suspected that this effect was produced by a reaction against the somewhat crude anti-Hitler propaganda.

On the other hand I occasionally noticed a rather more doubting expression flit over the face of Eden, who understood enough German to be able to follow Hitler roughly. Some of Eden’s questions and observations showed he had considerable doubts about Hitler and what he was saying. ‘There are actually no indications,’ he once observed, ‘that the Russians have any aggressive plans against Germany.’ And in a slightly sarcastic tone he asked, ‘On what are your fears actually based?’

‘I have rather more experience in these matters than is general in England,’ Hitler parried, and added heatedly, throwing out his chin, ‘I began my political career just when the Bolshevists were launching their first attack in Germany.’ Then he went off again into a monologue on Bolshevists in general and in particular, which with translation lasted until lunch.

This first meeting, lasting from 10.15 a.m. until 2 p.m., passed off in a very pleasant atmosphere. Such at least was Hitler’s impression. ‘We have made good contact with each other,’ he said to one of his trusties as he left his office. Turning to me and shaking me by the hand, he added, ‘you did your job splendidly. I had no idea that interpreting could be done like that. Until now I have always had to stop after each sentence for it to be translated.’

‘You were in good form today,’ Eden said when I met him in the hall; we knew each other from many a difficult session in Geneva. I too was very satisfied with the first round of the Anglo-German talks.

The British party lunched with von Neurath, after which the discussion was resumed. On the German side, von Neurath and Ribbentrop remained silent. Simon opened the session by advancing, in a very mild and friendly way, the British reservations regarding Germany’s unilateral denunciation of the Treaty of Versailles, while Eden reverted to German fears of Russia’s aggressive intentions. ‘Here the Eastern Pact could be of great service,’ he stated, thereby indicating the subject for the first part of the afternoon session. He outlined briefly the nature of such a treaty. Germany, Poland, Soviet Russia, Czechoslovakia, Finland, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania were envisaged as signatories. The treaty states should pledge themselves to mutual assistance in the event of one of the partners attacking another.

At the mention of Lithuania, Hitler showed anger for the first time. ‘We want nothing to do with Lithuania,’ he exclaimed, his eyes alight with anger. Suddenly he seemed to be a different person. I was often to see such unexpected outbursts in the future. Almost without transition, he would suddenly fly into a rage; his voice would become hoarse, he would roll his r’s and clench his fists while his eyes blazed. ‘In no circumstances would we enter a pact with a state that is crushing the German minority in Memel underfoot.’ Then the storm subsided as suddenly as it had begun, and Hitler was again the quiet, polished negotiator as he had been before the Lithuanian outburst. His excitement was explained by the fact that for months 126 citizens of Memel had been on trial for treason before a Kovno court martial, and the case was now nearing its end.

Speaking more quietly, Hitler refused an Eastern Pact on further and weightier grounds. ‘Between National Socialism and Bolshevism,’ he stated emphatically, ‘any association is completely out of the question.’ He added with almost passionate excitement, ‘Hundreds of my party members have been murdered by Bolshevists. German soldiers and civilians have fallen in the fight against Bolshevist risings. Between Bolshevists and ourselves there will always be these sacrificial victims preventing any common participation in a pact or other agreement.’ Moreover there was a third objection to the Eastern Pact – Germany’s justifiable mistrust of all collective agreements: ‘They do not prevent war but encourage it and promote its extension.’ Bilateral treaties were preferable and Germany was prepared to conclude such non-aggression pacts with all her neighbours. ‘Except Lithuania, of course,’ he said vehemently, but added more quietly, ‘as long as the Memel question remains unsettled.’

Eden put in another word for the Eastern Pact, asking whether this could not be combined with a system of bilateral non-aggression pacts or agreements of mutual assistance. But Hitler rejected this suggestion too, saying that one could not have two different groups of members within the framework of a general agreement. He was wholly averse to the idea of mutual assistance. Significantly he suggested instead that the individual countries should confine themselves to an undertaking not to assist an aggressor. ‘That would localise wars instead of making them more general,’ he said with apparent logic – but it was the logic of a man whose plan was to deal with his opponents one by one and who wanted to avoid having anyone standing in his way. At that time the motive behind his argument was not evident; it was to be revealed by his manner of proceeding later.

By some clever questions, Simon passed from the Eastern to the Danubian Pact, which was to be directed against interference in the affairs of the Danubian States. This proposal was based on a French scheme that aimed at preventing the annexation of Austria to Germany and putting up a barrier of treaties to impede the extension of Reich influence over the Balkans. I had been told at our Foreign Office that Hitler was particularly opposed to this idea for obvious reasons, and I therefore expected that he would give the British an emphatic ‘No’, but to my surprise he did not do so. ‘Fundamentally, Germany has no objection to such a Pact,’ he said in seeming agreement. I was rather surprised to hear him use the word ‘fundamentally’. At Geneva, when a delegate agreed en principe one knew that he would oppose the proposal in practice. Was Hitler using this old international device? His very next words confirmed my assumption; he observed almost casually, ‘but it would have to be stated quite clearly how so-called non-interference in the affairs of the Danube countries should be most accurately defined’. Simon and Eden exchanged a quick look when I translated these words, and I felt suddenly as though I were back at Geneva.

That afternoon the British also raised the question of the League of Nations. ‘A final settlement of European problems,’ Simon said quietly but emphatically, ‘is unthinkable unless Germany becomes a member of the League of Nations again. Without the return of the Reich to Geneva the necessary confidence cannot be restored amongst the peoples of Europe.’

On this matter too Hitler was by no means as intransigent as I had expected. Indeed, he stated that a return of Germany to the League was well within the bounds of possibility. The ideals of Geneva were thoroughly praiseworthy, but the manner in which they had been put into practice to date had given occasion for far too many justified complaints by Germany. The Reich could return to Geneva only as a completely equal partner in every respect, and that was impossible so long as the Treaty of Versailles was linked with the League covenant. ‘Moreover, we would have to be given a share somehow in the system of colonial mandates if we are really to consider ourselves as a power having equal rights,’ he added quickly, but immediately avoided any further discussion of the colonial question with the remark that Germany had at that time no colonial demands to bring forward.

This conversation was continued until 7 p.m., half of the time being naturally taken up with my translation and Hitler, as was his wont, constantly repeating himself on matters about which he felt strongly. Moreover, in the absence of both chairman and agenda, discussion tended to ramble. On the whole, however, it passed off better than I had at first expected, although after the cordial atmosphere of the morning I felt that the British had cooled off a little, no doubt owing to the fact that, despite his marked friendliness and his skilful recourse to Geneva formulas, Hitler had actually said ‘No’ to every point.

Von Neurath gave a dinner in honour of the British visitors, which was attended by about eighty guests, including Hitler, all the ministers of the Reich, many Secretaries of State, leading figures of the Nazi Party, Sir Eric Phipps the British Ambassador and the senior members of his embassy.

I sat next to Hitler, but most of the delectable dishes were whisked away untouched while I was delivering my translation, with the result that I left the table hungry. I had not yet devised the technique of eating and working at the same time – while my client stopped eating to give his text I would eat, and then deliver my translation while he ate. This procedure came to be recognised by chefs de protocole as an ingenious solution for interpreters at banquets.

The following morning was devoted to a detailed discussion of German armaments. At first there was some tension between Simon and Hitler as Simon propounded once again the principles governing the British position, emphasising especially that a discussion of the level of German armaments did not imply that Britain had departed from her original position. She adhered strictly to the view that treaties could be altered only by mutual agreement and not by unilateral denunciation. Hitler replied with his well-known thesis that it was not Germany but the other powers that had first broken the disarmament provisions of the Treaty of Versailles ‘by failing to carry out the clearly expressed undertaking to disarm themselves’. He added with a laugh, ‘Did Wellington, when Blücher came to his assistance, first enquire of the legal experts at the British Foreign Office whether the strength of the Prussian forces matched what had been agreed under existing treaties?’

Both sides advanced their arguments without any acerbity, the British obviously taking pains to avoid any antagonism on this fundamental question. Such was my impression from the very cautious, almost deprecatory manner in which Simon expressed the British reservation. Hitler too was extremely moderate in his tone, compared with that of his public statements on disarmament, though he was not lacking in clarity. ‘We are not going to let ourselves be rattled on conscription,’ he stated, ‘but we are prepared to negotiate regarding the strength of armed forces. Our only condition is parity on land and in the air with our most strongly armed neighbour.’

When Simon asked him at what strength he estimated the armaments requirements of Germany under prevailing conditions, Hitler replied, ‘we could content ourselves with thirty-six divisions, that is, an army of 500,000 men.’ This, with one SS division and the militarised police, would satisfy all his requirements. The point was somewhat confused by the fact that Hitler, while naming the SS, denied almost in the same breath that the party organisations in general had any military value, as Heydrich had done before him at Geneva. No doubt remembering the Geneva discussions on this question, in which he had taken part as British delegate, Eden expressed doubt as to whether the party organisations could be considered as having no military value and said that they should be regarded at least as reserves.

Wishing to avoid lengthy debate on this very controversial point, Simon immediately steered the discussion to the matter that at that time interested the British above everything: the question of the Luftwaffe. ‘In your opinion, Herr Reichskanzler,’ he asked, ‘What should the strength of the Luftwaffe be?’

Hitler avoided making any precise statement. ‘We need parity with Great Britain and with France,’ he said, adding immediately, ‘of course, if the Soviet Union were to augment its forces materially, Germany would have to increase the Luftwaffe to match.’

Simon wanted more information: ‘May I ask how great Germany’s air strength is at the present time?’

Hitler hesitated, and then said, ‘we have already achieved parity with Great Britain.’ Simon made no comment. For a while nobody said anything. I thought the two British delegates looked surprised and also dubious at Hitler’s statement. This impression was later confirmed by Lord Londonderry, Minister for Air, at whose conversations with Göring I was almost always present as interpreter. The subject of Germany’s strength in the air in 1935 cropped up constantly, as well as the question of whether Hitler’s statement on that occasion had not, after all, been exaggerated.

Hitler and Simon also discussed briefly the conclusion of an air pact between the Locarno powers. Under such an agreement the signatories to the Locarno Treaty would immediately render mutual assistance with their air forces in the event of an attack. ‘I am prepared to join such a pact,’ Hitler said, repeating an assent given previously. ‘But of course I can only do so if Germany herself has the necessary air force available,’ he added with a logic to which the British had no reply.

Hitler himself introduced the question of naval strength, making the demand, later to become famous through the Naval Agreement, for a ratio of 35 per cent of the British fleet. The British did not say how they stood with regard to this proposal, but since they raised no objection it could well be assumed that inwardly they agreed.

At noon, a lunch was taken at the British Embassy, at which Hitler made an appearance; this was the first time he had ever been seen at a foreign embassy. Göring and other members of the government were present. In the reception room, the British Ambassador Sir Eric Phipps lined up his children to give the Hitler salute and, so far as I recall, they even greeted Hitler with a rather bashful ‘heil’.

Immediately afterwards discussions were resumed at the chancellery, but no new points came up on the main subjects. Hitler took up much time with his favourite theme, Soviet Russia. He was particularly vehement about Soviet attempts to push westwards, and in that connection he called Czechoslovakia ‘Russia’s arm reaching out’. Hitler’s second obsession at this discussion was German military equality. The Reich must of course have all the classes of armaments that other countries possessed, but he was prepared to cooperate in agreements whereby armaments defined at Geneva as offensive weapons would be prohibited. Similarly, Germany could agree to supervision of armaments, but of course only on the basis of parity and on the assumption that such supervision were simultaneously exercised over all the other countries concerned.

Simon and Eden listened patiently to all this, with its many repetitions. I often thought of the disarmament negotiations at Geneva. Only two years ago the skies would have fallen in had German representatives put forward such demands as Hitler was making now as though they were the most natural thing in the world. I couldn’t help wondering whether Hitler had not got further with his method of fait accompli than would have been possible with the Foreign Office method of negotiation. I was especially inclined to think this when I observed how placidly Simon and Eden listened. Naturally they had their reservations and had evidently maintained the line of fidelity to agreements and of security guarantees in the familiar Geneva manner. Indeed, they had been emphatic to Hitler on these matters. Nevertheless, the mere fact of their presence and of this discussion about things that for years had been completely taboo at Geneva greatly impressed me.

These memorable days were concluded by an evening reception given by Hitler to a select company in the old Brüning chancellery. The furniture, carpets, paintings and even the flower arrangements in the reception rooms were harmonious and tasteful, the colours and the lighting not brash. The host himself was unassuming, sometimes almost shy, although without being awkward. During the day he had worn a brown tunic with a red swastika-armband. Now he was wearing tails, in which he never looked at ease. Only on rare occasions did I see him in his ‘plutocratic’ rig and then he gave the impression that the tails were hired for the occasion. That evening, in spite of his frock coat, Hitler was a charming host, moving amongst his guests as easily as if he had grown up in the atmosphere of a great house. During the concert items – I think Schlusnus, Patzak and the Ursuleac sang, mainly Wagner – I had ample opportunity of observing the British. Simon’s friendly interest in Hitler struck me even more than during the negotiations; his gaze would rest on him for a while with a friendly expression, and he would then look at the paintings, the furniture and the flowers. He seemed to feel happy in the German Chancellor’s house.

Eden also took in his surroundings with obvious interest and liking, but his expression indicated a sober, keen observation of men and things. I did not see the friendly warmth in his eyes that I believed present in Simon’s. His deprecation was clearly evident, except with regard to the musical entertainment, which he followed with unqualified admiration.

Of the Germans present, Foreign Minister von Neurath alone was unconstrained and natural in his demeanour. All the others, especially Ribbentrop, at the time Commissioner for Disarmament Questions, were vague and colourless, like subsidiary figures indicated by an artist in the background of an historical picture.

Towards 11 p.m., Eden left for Warsaw and Moscow. In Hitler’s entourage this visit to Stalin was taken much amiss, and an old National Socialist at the chancellery said to me, ‘It is sheer tactlessness of Eden to go on to the Soviet chieftain immediately after his visit to the Führer.’ Somewhat later Simon went back to the Hotel Adlon and then flew to London next morning.

As I left next morning for trade negotiations in Rome, I learnt nothing further of the direct impression that the British had made on Hitler. Hitler had spoken very appreciatively about Simon in the short intervals during the negotiations, and I heard him say to Ribbentrop, ‘I have the impression that I would get on well with him if we came to a serious discussion with the British.’ His opinion of Eden was more reserved, mainly because of the questions that Eden had put during the negotiations in order to elicit Hitler’s intentions on particular matters. Hitler disliked definite questions, particularly in negotiations with foreign politicians, as I often had occasion to note when working for him. He preferred general surveys on broad lines, historical perspectives and philosophical speculation, evading any concrete details, which would reveal his real intentions too clearly.