Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

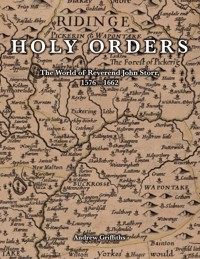

Reverend John Storr M.A., my 8th great grandfather, was the Vicar of Appleton-le-Street Parish in Yorkshire's North Riding from 1606 to 1662. He was ordained in 1600, while Queen Elizabeth was still on the throne and, despite opposing the Puritan faction, managed to hold onto his cure until the Restoration of Charles II, until his death at an advanced age. Besides a sketch of John Storr's life, the reader will find in these pages much additional material about the religious and social environment in which he and his descendants lived. He will also make the acquaintance of some of John's more colourful contemporaries.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 159

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Foreword

Context

Ryedale and the Vale of Pickering

Origins

Hutton Buscel

Old Malton

Appleton-le-Street

A twopenny whore

A fox unkenneled!

Stephen Jerome, Puritan preacher

Murder?

Conjugal affection

Reverend John Storr’s family

Marriage under the Commonwealth

Old Malton in 1678

New Malton in 1732

Selby and Owston Storrs

Obstinate and quaking speakers

They Kept Faith

Afterword

Foreword

Reverend John Storr M.A., my 8th great grandfather, was the Vicar of Appleton-le-Street Parish in Yorkshire’s North Riding from 1606 to 1662. He was ordained in 1600, while Queen Elizabeth I was still on the throne and, despite opposing the Puritan faction, managed to hold on to his cure until the Restoration of Charles II.

Besides a sketch of John Storr’s life, the reader will meet some of his more colourful contemporaries and find much additional material about the religious and social environment in which John Storr and his descendants lived. Some of this material comes from the files of the Borthwick Institute for Archives at the University of York, which has made a major contribution to historical research in Yorkshire by making the records of the Diocesan Courts of the Archbishopric of York available to a wider public.

A schematic chart of the various branches of the Storr family will be found at the end of the book.

Andrew Griffiths in February 2024 Ober-Ramstadt, Germany

Frontispiece

All Saints Church, Appleton-le-Street, in 2013

Cover illustration

Map of North Yorkshire by John Speed, 1610 (Bibliothèque Nationale de France, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Context

Religious conflict was endemic in the Tudor and Stuart era, and several of my ancestors were in the thick of it. One of these was my 9th great grandfather Reverend Charles Chauncey, a Puritan divine, who emigrated to New England in 1637 after facing disciplinary action resulting from his dogmatic views. Another was my Quaker 8th great grandfather Robert Kingham, a Buckinghamshire miller, who was fined and had his goods distrained for non-payment of tithes and refusal to swear an oath in the 1670s.

In order to understand the situation in which my ancestor John Storr found himself, it may be useful to recapitulate some of the troubled ecclesiastical history of the period.

It all began, of course, with Henry VIII and his break with the Church of Rome. After a brief return to Rome’s influence under Queen Mary, Henry’s “Church of England” became “established” under Elizabeth I through her 1559 Act of Uniformity and the obligation to use her revised version of Archbishop Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer.

James I began his reign with conciliatory motions towards Catholics, but their persecution was intensified after the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, and the King introduced an Oath of Allegiance in 1606, which repudiated the authority of the Pope in drastic words. Ministers of the Church and other public officials were obliged to swear it.

Among the Roman Catholics who adhered to the “Old Faith”, was the family of Michael Pallister, a weaver of South Kilvington, near Thirsk in the North Riding of Yorkshire. He was another of my 9th great grandfathers and he was penalised several times for recusancy1. One of his cousins was even executed for his faith; this was Thomas Palliser (sic), a Catholic priest and martyr, who was hanged, drawn and quartered on August 9th 1600 at Durham. He was honoured with the title “Venerable” in 1987, by papal decree.

The main threats to the Anglican Church in the early 17th century, however, were not really the Roman Catholics, but the Puritans and Presbyterians, who held that the work of Reformation, which had begun with Luther and Calvin, was unfinished. Charles I succeeded to the throne in 1625 and his tussle with Parliament over the limits of royal power led eventually to the Civil War, but he had also antagonised the Scottish Presbyterians and the Puritans by marrying a Roman Catholic and introducing changes to church practice that they objected to. One of these was a so-called “Book of Sports”, which allowed some forms of recreation on Sundays. Charles Chauncey’s refusal to endorse this in his church was one of the reasons for his chastisement and consequent emigration to America. In 1643, Parliament ordered the book to be burned.

The Civil War ensued in 1642, Charles was executed in 1649, and the Puritans were in the ascendancy until the Restoration of Charles II in 1660. During the “Interregnum”2, many parish priests who held to the old ways were dismissed and replaced by Puritan divines (sometimes termed “intruders” by their successors) and from 1653 on, marriages had to be performed by magistrates, instead of by clergy in churches. The Quaker movement emerged during the same period.

Under Charles II, the Act of Uniformity of 1662 resulted in the “Grand Ejection” of thousands of Puritans from the Church of England, among whom was my 8th great grandfather Isaac Chauncey, son of Reverend Charles. He joined the Congregationalists – a non-conformist community, whose principles were Puritan in nature.

The oppression of the Quakers was exceptionally severe, not only because of their recusancy, but also their dogmatic refusal to pay tithes, bear arms or swear any kind of oath. This brought them into conflict with the civil as well as the religious power and resulted in much persecution and suffering. The Quaker branch of the Storr family was a case in point.

This was the treacherous environment, in which the career of Reverend John Storr, Master of Arts and Clerk in Holy Orders, unfolded.

1Recusancy Refusal to attend the services of the Protestant Anglican Church. The recusancy laws enacted under Elizabeth I in 1559 provided for heavy fines. They were aimed principally at Roman Catholics, but they were also applied to Quakers.

2Interregnum The period between the execution of Charles I in 1649 and the Restoration of Charles II in 1660. The “regnal calendar“, counts this period as part of the reign of Charles I.

Ryedale and the Vale of Pickering

The River Derwent rises on the North York Moors about twelve miles north-west of Scarborough. It flows southward initially, past Ayton and Hutton Buscel, then turns west and meanders along the broad Vale of Pickering, between the Moors on its right and the Wolds on its left, to Old Malton, where it is joined by the River Rye and turns again southwards to pass York on the east and eventually join the Ouse and the Humber. The history of the Storrs also follows the river from Hutton Buscel to the Maltons, Old and New, and from there it takes the ancient Roman Road along the north flank of the Howardian Hills to Appleton-le-Street. This is a beautiful part of the country, which has been farmed and fought over for centuries.

Malton (taking New and Old Malton together) was the principle market town in the Ryedale wapentake3. The Lords of the Manor in the 1500s and 1600s were members of the Eure family (probably pronounced “Ewry” in those days). A Sir Ralph Eure was buried at Hutton Buscel in 1539 and his descendant Ralph, the 3rd Baron Eure, was Lord of Malton Manor until 1617, when he was succeeded by his son Sir William, the 4th Baron (1579-1646). William, who was a recusant Catholic, got deeply into debt and barricaded his estate of Malton Castle in 1632 to prevent the bailiffs from getting in. Sir William was buried at Old Malton in 1646, predeceased by his two sons: Ralph, who was killed in a duel in 1640 and William, who died on the Royalist side at the Battle of Marston Moor in 1644. The baronetcy passed to a grandson who died in 1652 and then to more distant cousins.

Malton Castle was garrisoned by the King’s forces in the Civil War and besieged. What remained of it was demolished in 1674 by order of the Sheriff, and the stones divided into two piles; one for each of the two daughters of the Eure family who had quarrelled over their inheritance and asked the Sheriff to mediate. Nothing is left of Malton Castle today except the gatehouse, which is now a hotel.

Malton has always been predominantly an agricultural town with an important cattle market, but it was also a communication hub, located at the point where the road from York to Pickering intersected the old Roman road to Helmsley. Coaches with travellers between York and Scarborough would stop at Malton, the docks on the River Derwent were busy with coal and farm produce, and the railway opened in 1845. Brewing of beer and tanning of leather were important local industries.

3Wapentake The subdivision of a county, equivalent to the Saxon “Hundred”, probably derived from the brandishing of weapons as an expression of approval when the chief of the wapentake entered upon his office (Merriam Webster)

Origins

“Storr” is a very old family name, dating from 1200 at least. Two theories have been advanced to explain its origin: it may be a word of Scandinavian origin meaning someone of powerful stature, or it could be a place-related name derived from the Middle English storth ‘brushwood; young plantation’4. Very likely there were multiple origins, arising in different parts of the United Kingdom.

In the 16th century, the name was particularly common in Lincolnshire and Yorkshire, and in these areas the Danish origin appears more likely, as both counties stood under Danish influence for centuries.

One on-line source says:

“The personal bynames “Stori” and “Estori”, from the Old Norse “storr”, Old Danish “stor”, great, large, are recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086. Early examples of the surname include: John Stor, [from] the Calendar of Letter Books for London, dated 1290, and Thomas Storre, noted in the 1379 Poll Tax Returns Records of Yorkshire. Storr, with variant forms Stor(e), Stor(e)y, Storry, Storie and Storrie, is particularly well recorded in Yorkshire Church Registers from the mid 16th century.”5

Besides the church registers, we can also consult the Hearth Tax6 records for Yorkshire, 1662-1674, which counted some 30 households headed by a man with the name Storr (including Storre, Stor and Store, but excluding Storrie, Storrey etc):

North Riding, 27 Storr households in six wapentakes (Hearth Tax of 1673):

~ Langbargh (4)

~ Whitby Strand (4)

~ Pickering Lythe (14) (including one William and three Johns in Hutton Buscel)

~ Hang East (1)

~ Bulmer (3)

~ Ryedale (1) (John Storr of New Malton)

East Riding, 5 Storr households in two wapentakes (Hearth Tax of 1672):

~ Holderness Middle Bailiwick (1) (Marmaduke Storr of Owstwick)

~ Kingston upon Hull (4)

West Riding, 1 Storr household in one wapentake (Hearth Tax of 1673):

~ Osgoldcross (1) (John Storr of Armin or Airmyn).

The particular branch of the Storr family that this work focusses on, stems from the wapentakes Pickering Lythe and Ryedale. From there, the Storrs spread to the south of the shire (Marmaduke Storr of Owstwick, for example, was connected to the Hutton Buscel Storrs), but I have not found any connection to the Lincolnshire Storrs, even though they only lived on the other side of the River Humber.

John Storr of New Malton (1630-1685), who appears in the above list, was named in all four surviving hearth tax returns, for the years between 1662 and 1673, with either three or four hearths, according to the year, which is indicative of a substantial household. This John Storr is my 7th great grandfather, but he is not the Reverend John Storr of my title. His story began a hundred years before the hearth tax was levied.

4 Dictionary of American Family Names 2nd edition, 2022

5https://www.surnamedb.com/Surname/Storr

6Hearth tax A property tax calculated according to the number of hearths, or fireplaces. It was first imposed in 1662 to finance the Royal Household of the recently restored Charles II, and amounted to two shillings per hearth and year.

Hutton Buscel

The village and parish of Hutton Buscel lies six miles from Scarborough on the road to Pickering. It was named after a Norman lord, Reginald Buscel, and is pronounced, and sometime spelled, “Bushel”. The parish is only half a mile wide, sandwiched between Wykeham and Ayton, but it stretches three miles north (towards the moors) and two miles south of the road. A descendant of the Hutton Buscel Storrs, who was born in 1832, wrote “the Storrs of our branch are very tall, with fair hair, blue eyes, and oval faces”, which could hint at Danish forebears.

They were a respectable yeoman family, comfortably off, but not particularly wealthy. In 1558, a Robert Storr bought a house with lands in the hamlets of Newton, Preston and Hutton Buscel from the Marshall family of Pickering, and Robert and Thomas Storr – presumably his sons – extended the property with further purchases in the same area, in 1586 and 1594. Thomas was also connected with two Causes7 before the Consistory Court of York in 1594 and 1596 (in one case, he was the defendant in an action for slander). He (or another family member of the same name) also served regularly as a jury member at Quarter Sessions between 1608 and 1622, when he was sometimes styled “Yeoman of Ayton”. A Thomas Storr junior was involved in another property deal there in 1608. Three children, who touch on our story, were born there to a Thomas Storr (not necessarily all three to the same father): Thomas (1597), John (1599) and James (1611).

It is very difficult to sort the Hutton Buscel Storrs into families and genetic lines, deriving in part from the confusion surrounding the Civil Wars (1642-1651) and Cromwell’s Commonwealth (1649-1660) and corresponding gaps in the parish records. In the rest of this section I will try and organise the known facts and draw some reasonable conclusions, but the hasty reader may skip it with a good conscience and pass to the next chapter.

Reconstructing the family tree of the Hutton Buscel Storrs is like doing a really tough jigsaw puzzle without the picture on the box. Plenty of isolated facts about the family have been collected, but putting them in a logical framework that accounts for all the facts without violating Occam’s Razor8 is next to impossible, so I will present the facts first and then attempt to devise a “Grand Unified Theory” that accounts for them, without claiming that this is the only possible solution.

Among the earliest facts are the following purchases of houses and land in the Hutton Buscel area (Feet of Fines9 records).

1558

Robert Storr purchased a messuage

10

with land in Newton, Preston and Hutton Buscel from the Marshall family

1586

Robert Storr & William Kethe purchased 2 messuages and a cottage with lands in Hutton Buscel and Preston from the Eure family

1593

Thomas Storr with Thos Battye and William Clarke purchased 3 messuages with lands in Hutton, Preston, Wykeham, and Newton from Richard Marshall

Newton and Preston seem to have been farming hamlets in the distant past, which have since disappeared, leaving traces in the form of tracts of land named Newton Fields and Preston Fields, stretching northwards from the villages of Hutton Buscel and West Ayton. Wykeham Fields borders Preston Fields on the west, but is located in the neighbouring parish.

And, from the Hull History Centre Archives:

1603

A conveyance from Roberte Welburne of Muston to Thomas Johnson of Muston and John Storre of Huton Bushell, yeomen

Somewhat later, another purchase is made:

1608

Thomas Storr junior purchased a messuage, lands and rent in Preston, Newton and Hutton Buscel from William Clarke

If instead of “messuage with land” we read “farm”, then a pattern emerges of individual husbandmen11 seeking to establish themselves as yeoman farmers, cultivating their own land, but all within a fairly small compass.

Any attempt to reconcile the Storrs into a single family will have to consider the Robert Storr, who made the initial purchase, as the patriarch, born perhaps around 1525. The thirty-year gap between the first and the second purchase probably indicates that the two Roberts were father and son.

In several cases, members of the Storr family are described as being “of Preston” or “of Newton” (also of “Ayton” and “West Ayton” in the neighbouring parish), and the inheritance of property is an important factor to consider in this family reconstruction project.

Another issue, which is rather specific to this family, is the recurring one of sons who were sent to Cambridge to study for Holy Orders. There were four of these that we know of:

~ Rev. John Storr of our title, born ca. 1576, Vicar of Old Malton and Appleton-le-Street

~ Rev. Thomas Storr, born ca 1597, Curate of St Leonards and Vicar of Fylingdales

~ Rev. John Storr, born ca. 1599, Vicar of Helperthorpe and Rillington

~ Rev. William Storr, born 1675, Vicar of Worlaby in Lincolnshire.

Traditionally, one would expect the oldest son to inherit the land and a younger son to join the clergy. I have tried to work this principle into my Grand Unified Theory of the Storr family.

The registers of Hutton Buscel church reach back to 1572 for baptisms and 1598 for marriages, which ought to be an enormous help in such a project. Unfortunately, the records seem to pose more questions than they answer and there are significant gaps, especially during the Civil War and the early part of the Interregnum.

What we do know from the parish registers is that there were three Storr families in the 1570s and 80s headed by Robert, John and Francis Storr, all of whom were having children in the same period and might therefore reasonably be assumed to be sons of the progenitor Robert Storr. The difficulty is that in the following years, thirteen baby Storrs were born to fathers called Thomas (mothers are not named in this register) and closer analysis shows that there must have been three different Thomas Storrs having children between 1580 and 1611. From 1612 until 1653, there is a complete absence of Storr baptisms in the parish and, after that, the earlier surfeit of Thomases is replaced by multiple John Storrs. Three different John Storrs were assessed for Hearth Tax in Hutton Buscel in 1673, for example.

More facts come from Wills, in particular those of Thomas Storr and John Storr who died in 1615 and 1660 respectively. There is also an Inquisitione Post Mortem12 for another John Storr, who died in 1630. These tell us something about the heirs and their property, but nothing about the parentage of the deceased persons.

For one piece of the puzzle, we have an excellent witness in the form of a William Storr, whose father Robert left Hutton Buscel in 1674 to lease a large property called Scalm Park near Selby, south of the City of York. William kept a diary filled with fascinating information about his family and about Scalm Park in general.13