11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

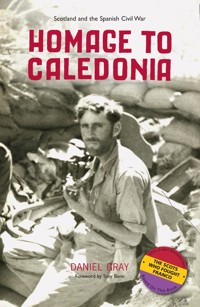

The Spanish civil war was a call to arms for 2,300 British volunteers, of which over 500 were from Scotland. The first book of its kind, 'Homage to Caledonia' examines Scotland's role in the conflict, detailing exactly why Scottish involvement was so profound. The book moves chronologically through events and places, firstly surveying the landscape in contemporary Scotland before describing volunteers' journeys to Spain, and then tracing their every involvement from arrival to homecoming (or not). There is also an account of the non-combative role, from fundraising for Spain and medical aid, to political manoeuvrings within the volatile Scottish left. Using a wealth of previously-unpublished letters sent back from the front as well as other archival items, Daniel Gray is able to tell little known stories of courage in conflict, and to call into question accepted versions of events such as the 'murder' of Bob Smillie, or the heroism of 'The Scots Scarlet Pimpernel'. Homage to Caledonia offers a very human take on events in Spain: for every tale of abject distress in a time of war, there is a tale of a Scottish volunteer urinating in his general's boots, knocking back a dram with Errol Flynn or appalling Spanish comrades with his pipe playing. For the first time, read the fascinating story of Caledonia's role in this seminal conflict. REVIEWS: As seen on STV Documentary 'The Scots Who Fought Franco'. 'Daniel Gray has done a marvellous job in bringing together the stories of Scots volunteers - in [this] many-voiced, multi-layered book' SCOTLAND ON SUNDAY'...moving and thought-provoking.' THE HERALD' A new and fascinating contribution' SCOTTISH REVIEW OF BOOKS 'Book of the week - Gray deserves applause for shining a light on a lesser-known aspect of the nation's character of which we should all be proud. 'PRESS &p; JOURNAL. BACK COVER: Thirty-five thousand people from across the world volunteered to join the armed resistance in a war on fascism. More people, proportionately, went from Scotland than any other country, and the entire nation was gripped by the conflict. What drove so many ordinary Scots to volunreer in a foreign war? Their stories are powerfully and honestly told, often in their own words: the ordinary men and women who made their way to Spain over the Pyrenees when the UK government banned anyone from going to support either side; the nuses and ambulance personnel who discovered for themselves the horrors of modern warfare; and the people back home who defied their poverty to give generously to the Spanish republican cause. Even in war there are light-hearted moments: a Scottish volunteer drunkenly urinating in his general's boots, enduring the dark comedy of learning to shoot with sticks amidst a scarcity of rifles, or enjoying the surreal experience of raising a dram with Errol Flynn. They went from all over the country: Glasgow, Edinburgh. Aberdeen, Dundee, Fife and the Highlands, and they fought to save Scotland, and the world, from the growing threat of fascism.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 339

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

DANIEL GRAY is a manuscripts curator in the National Library of Scotland. He is a graduate of Newcastle University. His first book, The Historical Dictionary of Marxism (Scarecrow Press), was published in 2007. Gray has worked as a researcher, contributor and writer on bbc radio and on STV’S 2-part documentary series The Scots Who Fought Franco. He has also written on football for When Saturday Comes and Fly me to the Moon, the fanzine of his beloved Middlesbrough FC. He is married to Marisa and lives in Edinburgh.

Praise for Homage to Caledonia

Daniel Gray has done a marvellous job in bringing together the stories of Scots volunteers… in [this] many-voiced, multi-layered book. SCOTLAND ON SUNDAY

[Gray] has organised a complex story into a well-constructed and compelling narrative. He can write – his prose is unfussy, fluent and warm. Best of all, he has squared the circle of producing accurate history while retaining a deep respect for the men and women who people it… moving and thought-provoking.

THE HERALD

Excellent… highly effective. THE SCOTS MAGAZINE

A new and fascinating contribution. SCOTTISH REVIEW OF BOOKS

Excellent… a rigorous, well written and entertaining assessment of Scotland’s contribution to that chapter of European history. Jamie Hepburn MSP,

HOLYROOD MAGAZINE

Book of the week… Gray deserves applause for shining a light on a lesser-known aspect of the nation’s character of which we should all be proud.

PRESS AND JOURNAL

A very human history of the conflict emerges.SCOTTISH FIELD

The latest addition to a line of excellent books detailing the efforts of British men and women in Spain. MORNING STAR

An excellent book I would recommend to anyone with an interest in the Civil War. SCOTS INDEPENDENT

Tells the story of those in Spain, but also of the tremendous effort of the Scots at home to raise funds to provide vital food and medical supplies. DAILY RECORD

Much of the testimony in this important book is new… What is most impressive is the way in which the different characters involved carry the reader along with them. From its pages, the voices of the ordinary Scots who volunteered to fight fascism ring out loud and clear… in no other book will you find yourself closer to them, or more inspired. INTERNATIONAL BRIGADES MEMORIAL TRUST NEWSLETTER

Daniel Gray skilfully weaves the words of the Scottish participants in Spain’s struggle for democracy in this excellent and timely book. THE CITIZEN

Told through the words and experiences of those who were there, this meticulously researched and beautifully written book is simultaneously heart-breaking and uplifting. MAGGIE CRAIG

Homage to Caledonia

Scotland and the Spanish Civil War

DANIEL GRAY

LuathPress Limited

EDINBURGH

www.luath.co.uk

First published 2008

Reprinted 2009

This edition 2009

eBook 2012

ISBN (print): 978-1-906817-16-9

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-909912-12-0

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Table of Contents

Foreword

Acknowledgements

Chronology of Events

The Stages of the Spanish Civil War

Introduction

Part 1

Chapter 1 - Connecting the Fight: Scotland in the 1930s

Chapter 2 - Bonny Voyage: Leaving Scotland, Arriving in Spain

Chapter 3 - Early Action: Brunete and Jarama

Chapter 4 - 'Esta noche todos muertos': Prisoners of Franco

Chapter 5 - Eating Onions as Apples: Life as a Volunteer

Chapter 6 - With the Best of Intentions: The Scottish Ambulance Unit

Chapter 7 - Red Nightingales: Nursing Volunteers

Part 2 - Scotland's War

Chapter 8 - The Home Front: Scottish Aid for Republican Spain

Chapter 9 - The Home Guard: The Reaction of Relatives

Chapter 10 - Scots for Franco: The Friends of National Spain

Chapter 11 - The Red, Red Heart of the World: Scotland's 'Other' Left

Part 3 - Spanish Stories, and Endings

Chapter 12 - Murder or Circumstance? The Bob Smillie Story

Chapter 13 - The Scots Scarlet Pimpernel: Ethel MacDonald

Chapter 14 - Last Heroic Acts: Aragon and the Ebro

Chapter 15 - Far From Perfect? Criticism and Dissent

Chapter 16 - The Unbitter End: Going Home and Being Home

Chapter 17 - 'Something to be proud of': Conclusions

Interviews and Printed Material Quoted

Archival Sources

Selected Bibliography

To Marisa, for everything

Picture it. The Calton. Fair Fortnight. 1937. Full of Eastern Promise. Wimmen windaehingin. Weans greetin for pokey hats. Grown men, well intae their hungry thirties, slouchin at coarners, skint as a bairn’s knees. The sweet smell of middens, full and flowing over in the sun. Quick! There’s a scramble in Parnie Street! The wee yin there’s away wae a hauf-croon.

Back closes runnin wae dug pee and East End young team runnin wae the San Toy, the Kent Star, the Sally Boys, the Black Star, the Calton Entry Mob, the Cheeky Forty, the Romeo Boys, the Antique Mob, and the Sticklit Boys. Then there wiz the Communist Party. Red rags tae John Bull. But if things wur bad in the Calton they wur worse elsewhere. Franco in the middle. Mussolini oan the right-wing. Hitler waitin tae come oan. When they three goat thegither an came up against the Spanish workers, they didnae expect the Calton to offer handers.

The heirs a John MacLean, clutchin a quire a Daily Workers, staunin oan boaxes at the Green, shakin thur fists at the crowds that gathered tae hear aboot the plight ae the Spanish Republic. Oot ae these getherins oan the Green came the heroes ae the International Brigade, formin the front line against fascism.

The Blackshirts, the Brownshirts, the Blueshirts, fascists of every colour an country came up against the men an women ae no mean city, against grey simmets an bunnets an headscarfs, against troosers tied wae string an shoes that let the rain in, against guns that were auld enough tae remember Waterloo. Fae nae hair tae grey hair they answered the call. Many never came back. They wur internationalists. They wur Europeans. They wur Scots. Glasgow should be proud ae them!

From the Calton to Catalonia, John and Willy Maley

Foreword

Daniel Gray’s important and powerful book Homage to Caledonia tells the story of those deeply committed and courageous Scots who volunteered to fight for democracy and socialism against General Franco and his forces – backed by Hitler and Mussolini – in the Spanish Civil War against an elected Republican Government.

The British establishment was openly sympathetic to the fascists, and its policy of ‘non-intervention’ was known on the left to be their way to stay clear so that Franco could win, but the left in Scotland rallied to the cause and apart from those who actually fought and died there, there was a great campaign to raise money and support.

As a teenager, I wrote a school essay in support of the republicans and against Franco on which my teacher wrote a one-word comment, ‘Disgusting’, so that told me a lot about him.

That war can be seen as a prelude to the second world war, and if Franco had been defeated, Europe might have escaped the horrors of 1939–45.

This book is very timely because the economic chaos that led to fascism seems to be threatening again today in the so-called ‘credit crunch’, which should remind us that the left has always to be vigilant.

Tony Benn, October 2008

Acknowledgements

I have been stimulated and encouraged by the kind help and knowledge of widows, sons, daughters and nieces of those who participated in the Spanish Civil War. In particular, David Drever, Annie Dunlop, Sandra Elders, Alan Murray, Sonna Murray, Sheila Stuart, Liz Pettie, and George and Nan Park all offered me stories, wisdom, and copious amounts of tea, cakes and soup. The words of Willy Maley were almost as great a motivation as the actions of his father. I am grateful, too, for their cooperation in allowing me to use the letters and archives of their relatives. Mike Arnott, Jim Carmody and Marlene Sidaway of the International Brigades Memorial Trust have been enormously helpful. Ian MacDougall’s written and spoken words have been of immense value, as has been the advice of Richard Baxell, Alan Warren and Don Watson. A grant from the Strathmartine Trust facilitated an extremely useful study trip to Spain.

Thanks are due to David Higham Associates for permission to use a quote from Muriel Spark’s The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. The unendingly patient and obliging Dr John Callow of the Marx Memorial Library deserves special praise, and thanks for permission to use quotes from the library’s International Brigades archive. Images and quotes appear courtesy of private collections belonging to the relatives of International Brigaders, and holdings of the National Library of Scotland (see Archival Sources, page 213). Photographs of the Scottish Ambulance Unit originally appeared in the Glasgow Evening Herald. Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders of material reproduced in the book. In case of any query, please contact the publisher.

At the National Library of Scotland, Maria Castrillo, Kenneth Dunn, Lauren Forbes, Cate Newton, Stephen Rigden, Robin Smith and Chris Taylor have been supportive in the extreme. Special thanks go to my translator Elena Fresco Barreira, the only Spaniard I know who uses the word ‘ken’. Gavin MacDougall has made Luath Press the ideal publishing house to write for, as well as supplying some outstanding ideas for the book, including the title. The support of his colleague Leila Cruickshank has also been invaluable, as has the assiduous work and treasured advice of my editor Jennie Renton.

The opinions expressed in Homage to Caledonia are those of the author and not of the publisher or any institution.

On a personal level, my mum and dad’s encouragement continues to know no bounds, and I cannot give thanks enough for the faith shown in me by Marisa, first a football widow, and lately a Spanish Civil War widow. Finally, my greatest, sadly posthumous, thanks must go to Steve Fullarton: quite simply, an inspiration.

Chronology of Events

1926General Strike, in which many future International Brigaders participated.

1931April: Second Spanish Republic proclaimed and reform programme instigated.

1932Inauguration of Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists.

1933November: victory for right-wing parties in Spanish general election. Halt of reforms programme.

1934Fifth National Hunger March to London.

1936February to June: Popular Front administration elected in Spain. Government of Manuel Azaña recommence and extend reform programme, exile military leaders, and ban the Falange Española.

12–13 July: José Castillo, then José Calvo Sotelo killed in Madrid.

17–18 July: Generals’ military uprising launched from Spanish Morocco.

20 July onwards: Hitler and Mussolini begin to supply the nationalists with military aid, while the Comintern agrees to help establish the International Brigades.

4 August 1936: the British and French governments sign Non- Intervention Treaty.

September onwards: Britain and major powers formally commit to non-intervention in Spain. Large numbers of volunteers begin to arrive to fight for the republicans, contributing to the defence of Madrid and assault on Lopera. In Britain, members of the National Unemployed Workers’ Movement march on London. Many future International Brigaders from Scotland participate.

October: republicans begin to receive military aid from the Soviet Union.

1937January: Foreign Enlistment Act invoked in Britain. British Battalion formed in Spain.

February: British Battalion take part in their first battle, at the Jarama Valley.

April: nationalist bombing of Guernica

May: Barcelona street-fighting.

June: Death of Bob Smillie.

July: British Battalion participate in the Battle of Brunete.

August: British Battalion transferred to the Aragon Front, and help to capture Quinto and Belchite.

October: British Battalion’s disastrous assault on Fuentes de Ebro.

December: British Battalion participate in the Aragon offensive and capture of Teruel.

1938January: British Battalion eventually succumb to the nationalist invasion of Teruel. From March, republicans retreat through Aragon, and Franco’s troops reach the Mediterranean, dissecting the Spanish republic.

July: British Battalion cross back over the River Ebro and participate in republican offensive.

21 September: Juan Negrin announces the withdrawal of international volunteers from the republican army.

28 October: British Battalion take part in parade of honour through the streets of Barcelona.

December: British Battalion members begin to arrive home.

1939February: British government recognises Franco as Spain’s sovereign leader.

1 April: nationalist victory complete.

1 September: Hitler invades Poland; beginning of World War Two.

Introduction

One of Joyce Emily’s boasts was that her brother at Oxford had gone to fight in the Spanish Civil War. This dark, rather mad girl wanted to go too, and to wear a white blouse and black skirt and march with a gun. Nobody had taken this seriously. The Spanish Civil War was something going on outside in the newspapers and only once a month in the school debating society. Everyone, including Joyce Emily, was anti-Franco if they were anything at all.

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, Muriel Spark

ON 7 MARCH 2008, under a leaden sky, several hundred people gathered in homage to the final survivor of a proud yet largely overlooked episode in Scotland’s history. Of 549 Scots who fought in the Spanish Civil War, Steve Fullarton was the last to die, adding a weight of poignancy to the sombre mood of those present at Warriston Crematorium, Leith. With him had gone Caledonia’s final active link to a conflict that defined the lives of an entire generation of Scots: it was in the Spanish Civil War, whether they participated directly or not, that their own struggles became embodied.

Documenting a selection of individual narratives, Homage to Caledonia brings Scotland’s contribution to events in Spain into focus: by showing not only the role of Scots in Spain but also the way in which the conflict impacted on life in Scotland, the book sets out to explain how and why this became Scotland’s war. It is a social history rather than a military one and is not intended to be a comprehensive history of the battles, politics and intricacies of the wider Spanish Civil War.

Reaction to hostilities in Spain must be viewed through the prism of 1930s Scotland; in the context of this highly politicised era, it is possible to appreciate why support for the republican government was so unequivocal. Popular modern perceptions of, for instance, communism are invalid, and hindsight largely irrelevant. The thirties were a time of intense idealism, of faith in democracy, anti-fascism and often of fealty to the Soviet Union, her atrocious excesses and distortions as yet unrecognised by most. More than obeisance to political dogma though, it was a time of sheer hope; a better tomorrow could be won through collective action, not just in Scotland, but in Spain too. To the Scottish working class, the struggles of the 1930s were the same struggles whether in Buckhaven or Barcelona. It is no coincidence that many of the Scots who fought in Spain referred to themselves as internationalists.

For many people, the primary impression of Scotland’s relationship with the Spanish Civil War has come from Muriel Spark’s The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, in which a schoolgirl, Joyce Emily Hammond, travels to fight for Franco as a response to the fascistic, doctrinaire education she receives from the book’s eponymous teacher. Joyce Emily is killed before witnessing any action: even in the insular bourgeois world of a conservative Edinburgh girls’ school, the Spanish Civil War in all its brutal colour could not be avoided.

The Scottish people responded with alacrity to the coup d’état launched by General Francisco Franco and his cabal of supporters on 18 July 1936. That coup was both the culmination of years of simmering tensions, and the trigger for a fierce war involving troops from across Europe; truly, it was Spain’s Archduke Franz Ferdinand moment.

Spain in the 1930s was a land of schisms between monarchists and republicans, Catholics and those opposed to the social, political and economic power of the church, and feudal landowners and peasants. That latter group, impoverished and largely illiterate, made up a substantial proportion of the Spanish population and constituted the main support base of the reformist republican government, which was elected on 16 February 1936.

The new ‘Popular Front’ government of Manuel Azaña, a figure reviled by conservatives, monarchists and military leaders, recommenced a series of political and social reforms halted in 1933 by the election of a right-wing regime (the original reforms had been instigated in 1931 with the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic, and had included the enfranchisement of women, the legalisation of divorce, a reduction of the military’s size and influence, and the redistribution of feudal land amongst peasants). In a frenzied atmosphere of flux, new legislation was also introduced, enhancing the rights of peasants and penalising the landed aristocracy. Spain’s reactionary establishment were outraged. Their ire was accentuated when the government sought to extinguish a threatened rebellion by exiling and isolating military chiefs including Franco, who was banished to Spanish Morocco. These actions heightened unrest among the government’s opponents and, supported by the newly outlawed right-wing Falange party, Franco and his military cohorts Emilio Mola, Juan Yague and José Sanjurjo began plotting a coup.

In the summer of 1936, Spain reached breaking point. On 12 July, a left-wing police officer in Madrid, José Castillo, was murdered by a fascist group, creating an incendiary mood and rioting. The following day, the left took its revenge: José Calvo Sotelo, leader of the conservative opposition in the Spanish parliament, was killed by Luis Cuenca, a commando with the civilian police. Though it is doubtful that the Popular Front government ordered the assassination of Sotelo, the slaying of a man who had virulently protested against Azaña’s reforms and openly admitted to being a fascist aroused the suspicions of the right, and exacerbated their feeling that an overthrow of the government was necessary. In this context, Franco and his henchmen launched their attack on the mainland from Ceuta in Spanish Morocco. Spain was at war.

The conspirators had anticipated a swift and comprehensive victory and, with the help of sympathetic army generals, were able to overrun swaths of southern Spain. They had not reckoned upon resistance from soldiers sympathetic to the republican cause and civilians fiercely protective of the elected government. Forming the republican side, an alliance of anarchists, communists, democrats, moderates, socialists and trade unionists sprang to the defence of that administration. Rather than conquering Spain rapidly and incisively, Franco and his nationalist army were left with isolated pockets of territory.

From the end of July, the nationalists began to receive significant military assistance from Adolf Hitler’s Germany and Benito Mussolini’s Italy. Crucially for the continuation of Franco’s early assault, German planes were provided to facilitate the mass airlift of his elite Army of Africa from Morocco to mainland Spain. For their part, the republican side received foreign assistance in the form of the volunteers that flocked over their borders to form militias and eventually the International Brigades, and, from October, materiel and troops from the Soviet Union. Rather than a civil war, then, Spain’s conflict became one of foreign intervention.

The Scottish desire to intervene was, in that sense, typical, though in its scale it was unique. Of the estimated 2,400 men and women who left Britain to serve in Spain, about 20 per cent were from Scotland. This is especially impressive when one considers that Scots then comprised only 10 per cent of the population of Great Britain. There were, too, Scottish volunteers from groups unaffiliated with the International Brigades, such as those who travelled to serve with the Independent Labour Party (ilp) contingent. The mass base of Scottish support for the Spanish republic, though, centred around the phenomenally successful ‘Aid for Spain’ movements, which garnered support across class, party and gender. In the Spanish cause, Scotland found a place to channel its energies, and the country’s efforts outweighed those of any similarly populated area in Britain, or indeed the world.

PART 1

From One Struggle to Another

CHAPTER 1

Connecting the Fight:

Scotland in the 1930s

An empty stomach made an empty head think.

Tommy Bloomfield, Kirkcaldy

THE POLITICAL FIRES of 1930s Scotland burned and crackled unremittingly. Entertainment and education came from the soapbox oratory of radical street preachers; a truly open university. What a massive working class lacked in ha’pennies to rub together, it made up for with a bountiful grassroots democracy. Talking and listening on corners, men and women became inspired to struggle against poverty and fascism, domestic and foreign. Shortly before he passed away, Steve Fullarton described the often incendiary atmosphere in which future fellow International Brigader Jimmy Maley held court:

I always attended his meetings. The Communist Party organiser would say ‘it’s time we had a meeting’. If Jimmy was available, he would always go. So Jimmy would carry this collapsible platform up to Shettleston Cross and I would give a hand to take it up there. Or, sometimes it was to help with chalking the streets, announcing that tomorrow night there would be a meeting by the Communist Party and Jimmy Maley would be speaking. Sometimes we painted it with whitewash; the traffic was such then that you could do that.

Jimmy Maley was a provocative speaker. He knew that the Catholic young men would be there in force, repeating whatever lies had been issued to them from the chapel. They would come out with these ridiculous things, even too ridiculous to bother about. Jimmy would be right in there and would knock the feet from under them, would leave them speechless.

Their Scotland was one of communist councillors and Members of Parliament, and seemingly endless waves of strike action, protest marches, and demonstrations. Very early on in the Spanish war, this movement lent its categorical support to the republican side. When in August 1936 an Ayr businessman confirmed that he was refitting small aeroplanes to sell on to ‘Spanish agents’, 400 people turned up at a spontaneous protest meeting and passed a resolution demanding that none of the aircraft should end up in the hands of General Franco’s forces. Around the same time, in Kirkcaldy sympathetic pilots dropped pro-republican leaflets on crowds attending a British Empire air display and 2,000 copies of the communist Daily Worker’s anti-Franco ‘Spain Special’ were sold in two hours on a Saturday night at Argyle Street, Glasgow.

Kirkcaldy volunteer Tommy Bloomfield, right, with two fellow Brigaders.

Though home to a resilient and tenacious people, this seedbed of radicalism was afflicted by horrific levels of poverty and limited life expectancy: the Labour MP for Stirling, Tom Johnston, lamented that poor, slum-like housing had saddled Scotland with the highest death rate in northern Europe. Tommy Bloomfield of Kirkcaldy, who served two separate terms during the Spanish conflict, endured a life of crushing hardship familiar to many Scottish republican volunteers. Bloomfield worked from the age of 11, delivering milk and bread in the mornings and working evenings in a dance hall ‘called the Bolshie, owing to the politics of the man who ran it’. Unemployed at 16, he ‘obtained a job chipping the tar off casie sets at ninepence an hour. The contractor was so hard and greedy that if he saw you straightening your back, you were sacked.’ It was in this context that many Scots turned to left-wing politics as a vehicle for their passage out of scarcity. As Bloomfield later remarked, ‘An empty stomach made an empty head think.’

Members of the Scottish working class threw themselves from the dole queue and the soup kitchen into the maelstrom of progressive politics and all of the agitation and protest entailed therein. These were times of daily ferment and solidarity. In the first week of August 1936, 30,000 people marched against the government’s new means test-based Unemployment Regulations in Lanarkshire, while protests took place in the name of the same cause in Leith, Greenock and Kelvingrove. Incredibly, Glasgow City Council asked its citizens to campaign against the Regulations, and in the Vale of Leven the council voted 17 to two in favour of protest. Clydeside Rivet Boys went out on strike in solidarity, then in September 54 miners at the Dickson Colliery in Blantyre began a stay-down strike over pay and conditions. When the authorities refused to send down food or water for the men, tens of thousands of Lanarkshire miners walked out on strike in sympathy. The following month, Caledonian rebellion crossed the border into England, as 2,000 Scottish fisher girls at Great Yarmouth staged a lightning strike against low pay. According to the Daily Worker, ‘the girls suddenly threw down their gutting knives and rushed through the curing yards, their numbers growing as they shouted their demands’. The women were hosed down and restrained by police, their rebellion quashed, if not their spirits.

The protests of redundant workers were voiced most formally by the National Unemployed Workers’ Movement (NUWM). In autumn 1936, the NUWM organised a hunger march from Scotland to London in protest at the proposed use of means testing. The march was completed by a number of men who would go on to fight in Spain. As Scottish NUWM leader Harry McShane suggested, ‘many of them [marchers] understood the significance of the war, and some expressed the desire to fight in Spain for the republic’. One of them was Bob Cooney of Aberdeen, arrested for chalking slogans on to the road as the march passed through Dundee. On being bailed, Cooney vented his anger outside the police station:

Apparently, chalking is illegal in this democratic city. The first intimation I had of this was when two limbs of the law swooped down on me and carried me off in a manner which suggested that they had got hold of Public Enemy Number One.

The 700 marchers, divided into east and west parties, regularly faced similar obfuscation from local authorities as they progressed south, though they were welcomed, fed and housed by compassionate locals throughout the country.

The Scottish contingent arrived in London on 8 November 1936 to participate in a national demonstration at Hyde Park attended by up to 100,000 people. Thirty Fife marchers were invited to take tea in the House of Commons with the East Fife Communist MP, Willie Gallacher, who consistently gave them solid support in parliament, fulminating against means testing and attacking Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin with the words, ‘You preach humanity – let’s have some of it.’

After a week of action in London, many of the Scottish marchers were firmly of the belief that poverty and the Spanish war were essentially facets of the same struggle. As well as Cooney, marchers like John Lennox of Aberdeen and Thomas Brannon of Blantyre started to conclude that they could influence this struggle most by making their way to Spain. The Daily Worker had already championed this theme a fortnight into Spain’s war, beseeching readers to ‘Smash the means test! Support the Spanish workers’ fight for democracy!’

Underpinning these struggles ran a deep-seated antipathy to fascism, whether in Scotland or further afield. If, ran the consensus, fascism was not defeated in Spain, it would soon have to be defeated on an unknown and unparalleled scale at home instead; ‘Bombs on Madrid today means bombs on London tomorrow’ became a common slogan. The popular mood in Scotland was overwhelmingly anti-fascist, as was demonstrated by the outrage provoked when the Scottish Football Association arranged an October 1936 match against Germany at Ibrox Park, the home of Glasgow Rangers. In protest at the fixture, local William MacDonald summed up the mood when he wrote to the Daily Worker:

The Nazis have violated every law and rule of sportsmanship and decency, and yet they have the insolence to send a team of propagandists on to Glasgow, a socialist city noted for its love of freedom and democracy. There will be no football at Ibrox on that particular day: in the interests of peace and safety the magistrates of Glasgow should urge an entire veto of the match. In this they will have the loyal support of all lovers of peace and fair play. The Scottish people want no truck with the representatives of Hitler and von Papen. Our slogan and that of the trade unions should be: ‘No truck with the Nazi murderers’. If an impudent attempt is made to proceed with the match, I can visualise in Glasgow the mightiest protest demonstration of our time.

Despite the objections of MacDonald and others, the match did go ahead, Scotland running out 2–0 victors. A number of anti-Nazi protesters were arrested, their fury amplified by the raising above the ground’s main entrance of a swastika flag.

Archie Dewar, Bob Cooney and Bob Simpson, all Aberdonians who carried the anti-fascist fight from the streets of their home city to Spain.

Prior to fighting fascism in Spain, many Scottish volunteers were involved with domestic action against Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists (BUF). Key in the battle against fascism at home was the city of Aberdeen. There, a broad anti-fascist group, galvanised by opposition to the 1935 Italian invasion of Abyssinia, took hold with gusto.

Regular street meetings and demonstrations were held, with locals perhaps more acutely aware of British fascism than residents of other towns and cities, owing to the fact that Mosley’s BUF leader in Scotland, William Chambers-Hunter, was a local resident. Chambers-Hunter was later to leave the BUF after Mosley became, in his eyes, ‘too dictatorial’, which suggests, to put it mildly, that he lacked political foresight when he agreed to work for the Hitler-admiring Englishman.

After pre-advertised meetings ended in their being driven from the streets, local fascists attempted on many occasions to hold spontaneous convocations in Aberdeen, but a network of cyclists, scouts and transport workers quickly spread the word, allowing the city’s anti-fascists the chance to mobilise. As Bob Cooney remembered:

I felt we had to smash them off the streets. When the BUF arrived we’d shout ‘These are the black-shirted bastards who are murdering kiddies in Spain – spit on them, kids.’ Sometimes we’d be too late because the women had already dealt with them!

The link between Aberdeen and Spain manifested itself in local events shortly before the Spanish war began. An Iberian ship, the SS Eolo, docked in Aberdeen in early July 1936, its crew unaware that the reformist republican government in Madrid had decreed that all seamen should receive pay rises. Bob Cooney and local Communist councillor Tom Baxter boarded the Eolo to inform the crewmen of their rights. When the captain of the ship refused to grant the revised wages, the seamen immediately went on strike. They received support and gifts from local groups, and the Aberdeen Trades Council resolved to do all in their power to prevent a ‘blackleg’ crew being admitted onto the ship. After three months, the vessel was ordered back to Spain prompting tearful goodbyes on both sides.

One of those who fundraised for the crewmen was Aberdonian John Londragan, who later fought in Spain. In an amazing coincidence, while there, Londragan spotted a postcard of Aberdeen harbour in the window of a photography shop in a village near to Brunete. On enquiring, he was delighted and overwhelmed to find that the postcard had been sent home by a crewmember of the Eolo he had befriended, Juan Atturie.

Outside of Aberdeen, many other Scottish volunteers served their anti-fascist apprenticeships locally before widening the fight to Spain. Edinburgh councillor Tom Murray pioneered some effective use of bureaucracy, for example in arguing that the Edinburgh Parks Committee should turn down on the grounds of noise pollution a BUF request to use a loudspeaker for their rally at the Meadows in September 1937. The Committee duly obliged, and Mosley et al. abandoned the meeting. Usually, action against the BUF was far more direct, as in Aberdeen. Bill Cranston, an unemployed chimney sweep from Leith, recalled being involved in numerous street scrapes with fascists, drawing direct parallels between the struggles in Scotland and those in Spain:

Something I didn’t like at all were the Blackshirts, the British fascists led by Sir Oswald Mosley. Before we volunteered to go to Spain to help the Spanish republic defend itself against Franco, we used to read a lot about the treatment that the Jews were getting in London at the hands of Mosley’s fascists.

George Watters1, a volunteer from Prestonpans, intervened directly with Mosley as he spoke at the Usher Hall, Edinburgh on 15 May 1936:

I had a front seat and my job was to get up and create a disturbance right away by challenging Sir Oswald Mosley, which I did. At that particular time I had a loud voice, and Mosley wasn’t being heard. I was being warned by William Joyce, Lord Haw Haw, what would happen to me unless I was quiet. There was a rush and I got a bit of a knocking about and taken up to the High Street. When I was in the High Street I was accused by one of the fascists of having kicked him on the eye. His eye was split right across. So I just said at the time: ‘I wish to Christ it had been me, then at least I would have felt some satisfaction!’

Watters escaped with a fine of five pounds and his determination to continue the fight, whether in Midlothian or Madrid, intact. Also present at the Usher Hall was Donald Renton, another who later served in Spain. During Mosley’s speech, Renton, a future Edinburgh councillor, leant over the balcony and gave a stirring rendition of the ‘Internationale’, before being forcibly ejected from the building.

Opposition to fascism did not always take the form of organised political demonstration or counter-demonstration. For Steve Fullarton, challenging fascism was a visceral, personal reaction rooted in his sense of humanity. This was pivotal in persuading him to take up in Spain the fight he had waged in his native Shettleston:

Fascism was a terrible thing. And what it was doing to everybody; trade unionists and politicians who were not Nazis. Things like that. And of course it was the bombing, the bombing of civilians that really got on my nerves. I would go to the cinema and see that on the newsreel, see the women running with the bairns in their hands, eyes turned skywards for the planes, to see if they were coming. That was absolutely disgraceful in the twentieth century but it happened, I know it happened. And eventually that’s what drove me to offering to join the International Brigades. It was a straightforward thing to say I’d like to join them. All I could do was offer my services and hope it would be worthwhile.

This sense of moral crusade against fascism was apparent in letters sent home once Scotsmen had arrived in Spain. As Glaswegian Alec Park wrote on 27 January 1938:

You of course understand my reasons for coming here, my appreciation of the dangers of fascism, my bitter hatred of fascism and my great desire to have a go where the fight is hottest.

Whether motivated by political conviction or a heartfelt sense of right and wrong, Scots were resolutely moved to fight fascism at home and willing to export that fight abroad. This was underpinned by the notion that if it were not laid to rest in Spain, fascism would come to Britain in the shape of a second world war and subsequent invasion. Prevention of that wider conflict was at the forefront of volunteers’ minds, as Tom Murray wrote home:

If only the people of Britain could fully understand the utter brutality of fascism with its bombings of innocent people, they would rise in their wrath and come to the aid of the gallant Spanish people. If our people do not do this now, they cannot escape the necessity of doing much more later to save their own doorstep, and under much more difficult circumstances. On my first night here I was roused from bed by an air-raid alarm and had to spend a shivering time in a trench. I would hate to find that through indifference now my fellow-citizens of Edinburgh and Scotland were to find themselves in such close proximity to the stark realities of war.

In April 1937, Sydney Quinn, of Glasgow, wrote an emotional letter home to his son emphasising the same point:

I am writing this on the eve of going into action against fascism. Whenever I see the thousands of Spanish children streaming along the road away from the fascists, my thoughts revert back home, and I can see you and your brothers in the same circumstances if we don’t smash the fascist monsters here.

Contemporary press coverage of events in Spain may also have helped persuade Scots to volunteer. The News Chronicle, Daily Mirror and Daily Worker all outwardly supported the Spanish republic, though it was the latter of those three that offered the most vehement support. The Worker was no fringe newspaper, and doubled its British sales over the period of the Spanish war from 100,000 in 1936 to 200,000 in 1939. As credible historical documentation, however, much of its editorial content should be treated questioningly; the paper was unwaveringly Stalinist in this era, for instance greeting the USSR’s 1936 constitution with the headline: ‘Stalin Opens New World Era – One-sixth of Earth Rejoices in New Charter of Freedom’. Yet its impact in crusading for the Spanish republic is beyond doubt, spearheading as it did countless campaigns of financial support and offering steadfast backing to the International Brigades.

The Worker remained optimistic of imminent republican victory until the last days of the war, which can’t have gone unnoticed by would-be volunteers weighing up the chances of participating in a quick victory in Spain. More than anything, though, it was the images printed in the communist newspaper that provoked people into action. Just as Steve Fullarton had been disgusted at the movie reels he had witnessed of bombing raids on Madrid, so readers were outraged to see, from November 1936 onwards, graphic images of slaughtered Spaniards.

However, of far greater motivation than newsprint for joining the fight in Spain was the perceived failure of government, Labour Party and trade union policies towards the Spanish republic. The National Governments of Stanley Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain were deeply committed to a policy of neutrality. On 4 August 1936 the British and French governments signed a Non-Intervention Treaty making it illegal for the legitimately elected Spanish republican government and General Franco’s nationalists to purchase arms for self-defence. Additionally, the agreement prohibited signatories from sending troops to Spain. The pact was formalised on 9 September with the establishment of a 27 countries strong Non-Intervention Committee. The policy stood throughout the civil war, despite the evident flood of arms and troops supplied to the nationalist side in Spain by Germany and Italy. This myopia when it came to foreign assistance for Franco’s side led many of those who joined the International Brigades to believe that the British establishment were in surreptitious support of the military rebellion. Indeed, these misgivings were not without grounds: the British Ambassador to Spain, Henry Chilton, stated in 1937 that ‘I am awaiting the time when they shall finally send enough Germans to finish the war.’

When the London government realised that the Non-Intervention Agreement was failing to deter British volunteers from travelling to Spain to fight, it invoked the 1870 Foreign Enlistment Act, from January 1937. This made it illegal for British nationals to participate in Spain’s war, though in reality the Act proved impossible to enforce and its adoption was more of a symbolic gesture aimed at underlining the government’s policy of non-intervention.

The government’s determination to remain officially neutral had the ironic effect of becoming a recruiting sergeant for volunteers: if the elected representatives of the country were to do nothing about Franco’s coup d’état, then the burden would have to fall on individuals. George Murray, the International Brigader brother of Tom and Annie, who served in Spain as a nurse (see Chapter 7), displayed his contempt for governmental protection of Franco in a letter sent home from the front line:

The very thought of [Anthony] Eden and company makes my blood boil. ‘Franco should be granted rights’ – ‘rights’ for the murder of hundreds of thousands of children, women and men. No more reactionary, hateful and deceitful gang of crooks ever disgraced Britain.

Edinburgh’s John Gollan, a future leader of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) who visited Spain twice though didn’t fight, summed up the feelings of many volunteers to Spain when he claimed that the Non-Intervention Committee was ‘a screen behind which Hitler’s and Mussolini’s invasion has been carried out’. Interestingly, the policy of non-intervention had the consistent support of both the Glasgow Herald and The Scotsman, the latter printing an editorial on 22 February 1937 that asserted ‘the future government of Spain is a question which should be settled by Spain alone’.