9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

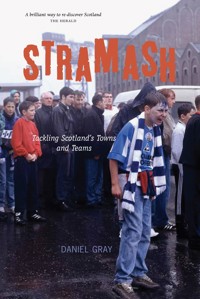

Fatigued by bloated big-game football and bored of a samey big cities, Daniel Gray went in search of small town Scotland and its teams. At the time when the Scottish club game is drifting towards its lowest ebb once more, Stramash singularly falls to wring its hands and address the state of the game, preferring instead to focus on Bobby Mann's waistline. Part travelogue, part history and part mistakenly spilling ketchup on the face of a small child, Stramash takes an uplifting look at the country's nether regions. Using the excuse of a match to visit places from Dumfries to Dingwall, Gray surveys Scotland's towns and teams in their present state. Stramash accomplishes the feats of visiting Dumfries without mentioning Robert Burns, being positive about Cumbernauld and linking Elgin City to Lenin. It is ae fond look at Scotland as you've never seen it before. REVIEWS: 'There have been previous attempts by authors to explore the off-the-beaten paths of the Scottish football landscape, but Daniel Gray's volume is in another league' - THE SCOTSMAN 'Truly splendid' - ARTHUR MONTFORD 'An excellent book about the country's smaller teams - [Stramash] captures the vague romance that still clings to these smaller Scottish clubs. It will make a must-read for every non-Old Firm football fan - and for many Rangers and Celtic supporters too' - DAILY Record' As he takes in a match at each stopping-off point, Gray presents little portraits of small Scottish towns, relating histories of declining industry, radical politics and the connection between a team and its community. It's a brilliant way to rediscover Scotland' - THE HERALD' A great read, because Gray doesn't write about just football, he uses football as an excuse to explore the histories of small towns in Scotland' - THE SKINNY 'Why do the Gers and Hoops have retail outlets in the capital? Why do buses depart for Glasgow on a Saturday morning from every corner of Scotland? Gray's book is a splendid attempt to answer these questions, and more besides - The result is sociology at its best, which is to say eminently readable - Stramash may turn out to be a memoir of the way we were, and an epitaph' - SUNDAY HERALD' I defy anyone to read Stramash and not fall in love with Scottish football's blessed eccentricities all over again - Funny enough to bring on involuntary laugh out loud moments' - THE SCOTTISH FOOTBALL BLOG

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 348

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

DANIEL GRAY is the author of the Saltire Award-nominatedHomage to Caledonia: Scotland and the Spanish Civil War. Since its publication, the book has been turned into a television series and Edinburgh Fringe show. Daniel’s previous book, co-authored with David Walker, was the Historical Dictionary of Marxism, for which they have still to sell the film rights. He has regurgitated the same jokes in the fanzine of his beloved Middlesbrough FC, ‘Fly Me to the Moon’, for the worst part of a decade. Daniel also reviews books for, among others, History Scotland, writes a column in The Leither magazine and has worked as a manuscripts curator and television researcher. He lives in Leith with his wife Marisa.

An excellent book about the country’s smaller teams… [Stramash] captures the vague romance that still clings to these ‘smaller’ Scottish clubs. It will make a must-read for every non-Old Firm football fan – and for many Rangers and Celtic supporters too.

DAILY RECORD

There have been previous attempts by authors to explore the off-the-beaten paths of the Scottish football landscape, but Daniel Gray’s volume is in another league.

THE SCOTSMAN

As he takes in a match at each stopping-off point, Gray presents little portraits of small Scottish towns, relating histories of declining industry, radical politics and the connection between a team and its community. It’s a brilliant way to rediscover Scotland.

THE HERALD

A great read, because Gray doesn’t write about just football, he uses football as an excuse to explore the histories of small towns in Scotland.

THE SKINNY

Why do the Gers and Hoops have retail outlets in the capital? Why do buses depart for Glasgow on a Saturday morning from every corner of Scotland? Gray’s book is a splendid attempt to answer these questions, and more besides… The result is sociology at its best, which is to say eminently readable… Stramash may turn out to be a memoir of the way we were, and an epitaph.SUNDAY HERALD

I defy anyone to read Stramash and not fall in love with Scottish football’s blessed eccentricities all over again… Funny enough to bring on involuntary, laugh out loud moments.

THE SCOTTISH FOOTBALL BLOG

Stramash

Tackling Scotland’s Towns and Teams

DANIEL GRAY

LuathPress Limited

EDINBURGH

www.luath.co.uk

First published 2010

Reprinted 2011

Reprinted 2012

eBook 2012

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-909912-28-1

Map © John McNaught

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

© Daniel Gray 2010

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction

A Note on Terms Used

Chapter 1 - Ayr

Chapter 2 - Alloa

Chapter 3 - Cowdenbeath

Chapter 4 - Coatbridge

Chapter 5 - Montrose

Chapter 6 - Kirkcaldy

Chapter 7 - Greenock

Chapter 8 - Arbroath

Chapter 9 - Dingwall

Chapter 10 - Cumbernauld

Chapter 11 - Dumfries

Conclusion - Elgin

Final League Tables 09-10

Note on Sources

Bibliography

To those that push the turnstiles in search

of a more splendid life.

WHAT WOULD SATURDAY be without the match? It is a glorious opportunity to blow off steam that has been gathering for a week. ‘Oucha dirty!’ ‘Pitimaff!’ ‘Dig a hole, Ref!’ And all the other choice expressions heard where the big ball is being banged.

Then a new world the next week. The man you dubbed a puddin’ is now the cat’s whiskers. His antics tickle you no end. ‘Give him the works’ – ‘that’s the stuff! – ‘shoot!’ – ‘Goa... hard lines, ower the baur.’

What an atmosphere. Every move charged with electricity. Some of the players charged with dynamite, at least that’s what it seems like to the poor fellow who gathers himself up from a sea of mud and politely asks the referee: ‘is this Sauchiehall Street or Tuesday?’

But it’s all in the game. The blokes in the work talk about it for weeks to come. You haven’t the slightest idea. I know a couple of the lads in one of the Clyde Shipyards who got into an argument one day. They were so engrossed, and at times so heated, that it was only when the watchman tapped them on the shoulders and asked them why they weren’t away for the Fair Holidays like everybody else they discovered they had been at it for the whole weekend.

Yes, that’s FOOTBALL!

Alloa Football Club: Official Handbook and Fixtures, 1947/48

Acknowledgements

I AM INDEBTED to the work of local and football club historians down the years. Without them, much social and footballing history would have been lost, and my hope is that readers of Stramash will support their work in future. Interviewees Bernie Slaven, Dick Clark, Duncan Carmichael, Ian Rankin, Jake Arnott, Jim Banks, John Wright, Karen Fleming, Robin Marwick and Vincent Gillen were helpful and fascinating, each in their own way as befits the diversity of their subjects and roles. John Simpson (Alloa), John Litster (Raith Rovers), Forbes Inglis (Montrose), Crawford (Clyde) and Giancarlo Rinaldi (Queen of the South) gave valuable advice on their own clubs’ chapters.

Michael Reilly of the Coatbridge Irish Genealogy Project was extremely supportive too. The vast majority of images in this book were provided by Mark I’Anson, artist supreme and a keeper of this nation’s football heritage. Aside from that, Mark’s advice and anecdotes were treasured, his insistence on feeding me broccoli less so. At Luath Press, enormous thanks must go to Gavin MacDougall for having faith in me again, my editor Leila Cruickshank for her patience and meticulousness, and Tom Bee for the cover. That cover features one of my all-time favourite pictures of anything, never mind football; I am grateful to Stuart Clarke. On a personal level, thanks to The Gaffer for forcing me into a second trip to Greenock, Paddy Dillon (www.thenetherregions.co.uk) for reminding me football could be funny (‘who do you werk for?’) and Robert Nichols at ‘Fly Me To the Moon’ for first publishing my piffle nearly a decade ago. My mum’s encouragement is as strong as ever, and hopefully a book about football makes sacrifices such as driving me to Chesterfield for a League Cup tie ‘to test out your new car’ (my words) worthwhile. This football gubbins really started with my dad at Ayresome Park in 1988; a million Midget Gems later and he’s still this Danny’s champion. Marisa’s love and support continues to be boundless and inspiring; one day I’ll get a real job so you can finally write your A History of the Babbity People.

www.stramashthebook.com

twitter.com/stramashthebook

Introduction

WHEN I MOVED TO Scotland from north-east England in 2004, I was amazed by how few people supported their local football teams. This was not the case in small towns alone, but in Edinburgh too. There, Rangers and Celtic tops were ubiquitous, and both clubs had retail outlets in the city.

I hadn’t even watched them play and already I was sick of the Old Firm. Their domination was similar to that of the chain supermarkets and cafés which had made visiting different high streets the equivalent of having a girl in every port who looked and sounded exactly the same. What had happened to those curious names of my youth like Partick Thistle and Queen of the South? These were team names, town names and names that didn’t appear on a map which had taken on an air of wonder and exoticism when I was growing up. There had been an otherness about those farthest reaches of the results on Sports Report as they were whispered from my dad’s car radio. When labelling these places ‘pools coupon towns’, writer Jonathan Meades defined what so many of us in England felt.

Scottish football was a mystery to me in my youth, and little changed in my first five years here. I didn’t help my own cause by failing to engage with it. At least twice a month, I’d make my way to Teesside to watch Middlesbrough, and that by choice. On spare Saturdays, I’d catch up with real life when really I should’ve adopted a second team here.

Gradually, I fell out of love with these Saturday and Sunday jaunts. On a match day, I remained happy with everything leading up to 3pm: the train journey down the striking east coast; the same old faces in the pre-match pub; the walk to the ground instilled with that feeling that anything might happen. Then, beyond the turnstile, I’d realise I had just contributed to the wages of Mido, a rotund centre-forward with the kind of hateable arrogance that made Liam Gallagher look like Little Voice (there are similes referencing events after the 1990s in this book, just not many). From 3pm my team, like so many others, would cagily set about surviving in the Premier League with all its ‘Sky money’, that catch-all excuse for boring football and the media career of Jamie Redknapp. This was existence for the sake of moneyed existence, and I wanted out, or at least to see if I could recapture my love of football elsewhere before realising I couldn’t and then returning sheepishly to the Riverside Stadium with a bunch of flowers and some chocolates. From August 2009, I would couple childhood intrigue with dwindling interest on a voyage of rediscovery.

This would not be about football alone. While researching my first book, Homage to Caledonia: Scotland and the Spanish Civil War, I’d briefly visited a number of small towns across Scotland, each of which had left me curious. Contrary to the parochial warnings of friends in the capital, these had been places of character and intrigue, and now I wanted to see more of them. From a social historian’s point of view – and I am partial to a leather elbow patch – if men and women from those towns had been internationalist enough to fight in the Spanish Civil War, then surely other events on a world scale lay beneath. As with the football teams I knew nothing of, what had been the roles of those towns? What part had they played in the making of Scotland and the world? Just as football here always seemed to be about the Old Firm (who, inevitably, pop up throughout Stramash, and are enjoyably beaten once or twice), history appeared to be forever linked to Edinburgh or Glasgow and kings or castles. This book is an attempt to pluck the likes of Cowdenbeath and Coatbridge from the footnotes and place them in the main text. In those pages which delve backwards to reach parts of football club histories untouched by mainstream accounts of the game, it is a reminder that their pasts are rich and worth losing ourselves in.

The football and town elements are by no means disconnected. The clubs were release valves for oppressed miners (Cowdenbeath); they were the result of philanthropic acts by Victorians in posh hats (Morton); and they were, glamorously, critically affected by the whims of the 1945 New Towns Committee report (Clyde). All were impacted upon by the World Wars.

There are modern trends which confirm the persistence of society’s influence on the game. As small town populations fall, so do small team attendances, and as people shun the diverse high street in pursuit of the homogenous out-of-town shopping mall, so too do they ignore their local teams and follow the giants of the globalised world, whether Rangers and Celtic, or Manchester United and Barcelona. I wanted to see how all of this had made the towns and teams of modern Scotland look, and see how exactly they had managed to survive in a world where big had generally defeated small. And, I wanted an excuse to drink in some different pubs.

Stramash is by no means a comprehensive history of any of those towns and clubs. Dumfries features without mention of Burns, and Ally MacLeod makes only a brief appearance in the Ayr United chapter. Indeed, much of the football history is confined to the pre-World War Two period, so short on highlights have the subsequent lives of the teams been. Rather than seeming irrelevant, I hope those pasts can provide mental refuge and imagined nostalgia for those that don’t even remember them; they certainly did for me.

At a time when the Scottish club game is drifting towards its lowest ebb once more, Stramash singularly fails to wring its hands and address the state of the game, preferring instead to focus on Bobby Mann’s waistline. Similarly, no attempt whatsoever is made to tackle these towns’ social problems, but every attempt to see the good.

There is no ‘challenge’ element to my travels, just the remit of visiting towns and teams with the intention of sketching their place in the world then and now. My only rule was to stay within the confines of the Scottish Football League, sadly leaving no room for, say, Junior football or the Highland League. My choices of town and team were often governed by Scotrail routes, fixture postponements and whether or not I could convince my wife that I really should miss another of her friend’s weddings to visit Cumbernauld (the answer was no, I shouldn’t, hence the midweek Clyde fixture). In a cynical world choked with sneering attitudes to admittedly imperfect places and players, Stramash is unashamedly positive about its subjects, and a wordy love-letter to local Scotland.

A Note on Terms Used

SCOTTISH FOOTBALL IS OFTEN maligned for being behind the times. In one department this is simply not so: that of pointless renaming and rejigging. Years before consultants charged £400 an hour to rebrand bin men as waste disposal officers, the game’s bosses were at it. Keeping up with the names of divisions is incredibly difficult, especially for the reader (for the writer, this just presents another chance for procrastinating instead of typing chapters; my ‘Development of the Divisions’ colour wallchart is beautiful). As such, I’ve used ‘Division One’ and ‘Division Two’ up until the 1975 shift (so, for example, post-war Divisions A and B are absent). After that, it’s Premier League (top tier), Division One (second tier) and Division Two (third tier), and from 1998 the current system of Premier League (top tier), Division One (second tier), Division Two (third tier) and Division Three (fourth tier). Still not clear? Well, it doesn’t really matter – by the time the book is published, it’ll be The Dobbies Garden Centre Caledonian Sector A.

Chapter One – Ayr

Ayr United 1 v 1 Partick Thistle, 8 August 2009

‘A…A…AH…A-CHOO.’ The gangly teenager behind the counter in WH Smith sneezed as if auditioning for a Lemsip advert. At the till, a mother dived in front of her child’s pushchair to cover him from snot shrapnel, while behind me three pensioners took shelter among the Women’s Lifestyle shelves. In the summer of Swine Flu, everyone lived on edge. Glasgow Central Station was awash with germs, mutual suspicion and Spanish tourists trying to work out the difference between Apex, peak and off-peak tickets.

By the ticket machines, an elderly couple in bright fleece jackets competed to see who could take the most time to make a purchase. ‘This,’ snarled the young bloke behind me, ‘is exactly why old people shouldn’t be allowed to use technology. They two are like my maw pointing the TV remote at the kettle.’

On the train for Ayr, Partick Thistle fans mixed with holidaymakers bound for Prestwick International, the former dreaming of promotion, the latter of accurately-named Ryanair airports. Above the hubbub, a woman gave her personal details over a mobile phone, speaking loudly and clearly as if regally proud of her mother’s maiden name. It’s a good job I’m no fraudster, or Sarah McKenna of 42 Binnie Street, Gourock, sort code 80-12-76, account 84615523, childhood pet’s name Twinkle, would be in deep trouble.

The train limped into Ayrshire and after Irvine the landscape became spotty with dunes. This was the rugged terrain in which Alfred Nobel experimented with explosives, and the Ardeer plant churned out munitions which were to alter the course of World War Two. Out of the window, Tenerife-tanned men hid all-inclusive holiday paunches in tank tops on a continuous strip of golf courses. Past them, Arran lurked majestically, a brooding presence set in glinting sea. Shortly after passing through Prestwick Airport, soon to be celebrating 50 years since Elvis Presley didn’t actually – shhhh – turn up on the tarmac there, we crawled into Ayr.

From the station, I crossed the road and paused to look at the Burns statue. Behind me, a painted sign advertised the ‘Bodystyle Adult Themeshop’ and ‘Budds: the wee bar with the big heart?’, the question mark implying that it was up to customers to decide. Continuing toward the sea, narrow streets flowed into the grandest of open spaces at Wellington Square. Surrounded on two sides by Georgian villas, the Square boasts the kind of bowling green lawn I am always desperate to perform a slide tackle on. Having won the ball, I’d then test the goalkeeper (a statue of the 13th Earl of Eglinton) with a daisy-cutter from 25 yards. Should the Earl fail to make a save, the ball would crash into the County Buildings.

Instead of sounding like a 1960s DSS tower block, the County Buildings deserve a more prestigious name. Their columned façade is nothing short of palatial. This stately appearance is more ambassador’s reception than council tax administration, though there is something admirably democratic about a building fit for kings being used to take planning decisions over bungalow extensions.

In front of the sea-facing end of the County Buildings sits the Steven Fountain, bright white, intricate and frilly. There, Victorian tourists would perch within envious view of inmates in the nearby prison, demolished in 1930. Peering from behind their iron bars, prisoners could look out to the ocean and listen to merry holidaymakers. Their agony was summed up by the jail’s bittersweet nickname; ‘The Cottage by the Sea’.

If, in their splendour, Wellington Square and the County Buildings sit uneasily with the traditional profile of British seaside resorts, The Pavilion across the road redresses the balance. Built in 1911 and quickly labelled ‘The White Elephant by the Sea’, ‘The Piv’ hosted dancing, roller-skating, boxing and variety shows for much of the 20th century. Its many guises have reflected the ebb and flow of British entertainment culture, from dancing troupes through to the rave scene, and now Pirate Pete’s, a (shudder) ‘Family Entertainment Centre’.

Ayr’s Esplanade spreads over two miles from the harbour to the mouth of the River Doon. It runs parallel to a landscape of sands equally handsome and haggard, and a sea of dark blues and islands beyond. From Pier Point, a clear day can bring into view Ailsa Craig to the south-west, Arran to the west, the Cumbraes and Bute to the north-west, and even the peak of Ben Lomond. Unfortunately, it was foggy and overcast when I went, so all I could see was a lady in a pink coat shovelling dog emissions into an Asda carrier bag. Poor weather or not, the situation of Ayr is undeniably dramatic, as an entry inGroome’s Ordnance Gazetteer of Scotlandfor 1885 concurred:

The entire place sits so grandly on the front of the great amphitheatre, with the firth sweeping round it in a great crescent blocked on the further side by the peaks of Arran, as to look like the proud metropolis of an extensive and highly attractive region.

This is an epic place, and even my no-nonsense VictorianPenny Guide to Ayrallowed time for contemplation, kindly offering to ‘leave you there to your own devices till you saturate your tissues with the ozone of the western ocean.’ Unfortunately, owing to a well-aimed shot of white backside paint from a devious seagull, sea spray was not all I saturated my tissues with.

The Esplanade’s vast expanse includes the Low Green, a giant communal field gifted to Ayr by William the Lion in 1205. In the 16th century, the town council enshrined in law Ayr residents’ right to use the land for games and recreation. It became a popular venue for football, with one of the area’s first teams, Ayr Thistle, playing here, and for years at Ayr United’s Somerset Park ground, the standard heckle for a clumsy player was ‘ye couldnae turn on the Low Green’. It was used, too, by the Royal Flying Corps as a landing strip in World War One, as a concert venue and as pasture for grazing animals, hopefully all at the same time.

With Low Green, Wellington Square and its outlook, Ayr oozes class and has none of the shabbiness that blights so many British seaside towns. Its qualities were well recognised in the Victorian era when it emerged as a prime holiday destination following the arrival in 1840 of a direct rail link with Glasgow. As theAyr Observerreported at the time, ‘It is impossible to foresee the full extent of the revolution which this new facility for transit is destined to produce.’

Thirty years later, theAyrshire Expresspublished a booklet entitledAyr as a Summer Residenceto proudly extol the town’s virtues. Appealing to ‘those denizens of Glasgow who live under its cloud of smoke’, the booklet boasted of how the locality’s

air of quiet contrasts pleasantly with the continuous rattle of city thoroughfares, and a stranger misses the noisome din of loaded lorries and carts, and crowded omnibuses and cabs, in constant procession.

Under a chapter entitled ‘Sanitary Aspects’, a headline sadly missing from modern holiday brochures, the author wrote of local health benefits:

It cannot be surpassed for pure air. Situated close upon the coast, at a moderate elevation above the sea, it is peculiarly exposed to the west winds, as purified by contact with its surface, and full of the elements of life, they sweep in from the ocean.

Having convinced the reader of the ‘lusty health’ available, a further chapter celebrated Ayr’s ‘Commercial Attractions’, claiming that ‘the freshness of the principal articles of diet is in itself a luxury to which residents in large cities are strangers.’ It’s amazing how romantic the Victorians could be about candyfloss and crabsticks. Never ones to eschew gender stereotyping, those same Victorians neatly broke down the entertainments on offer:

Ladies may enjoy the pleasure of shopping. Fancy warehouses and extensive drapery establishments provide the numerous essentials for the employment of nimble fingers in wet days and in evening hours, in knitting, sewing, tatting, &c., &c. Gentlemen who, from long-indulged custom, may deem it essential to their happiness that they should have an opportunity of ‘taking a look at the papers’ can have their habit gratified by becoming temporary subscribers to the Ayr Reading Room.

Mothers andScotsmanreaders alike were probably not reassured to learn that for children playing on the beach ‘accidental death by drowning’ was ‘almost impossible.’

The chance of death – always an important criterion when choosing a holiday destination – was reduced further from 1881 when Ayr Council undertook improvement works which included the building of a sea wall, toilets and bathing machines. For the first time they sanctioned donkey rides, presumably bringing an end to the dangerous and illegal leisure mule trade.

Ayr remained a hugely popular holiday destination well into the 20th century, its paddle steamer excursions a rite of passage for generations of Glaswegians. Many stayed in Billy Butlin’s sprawling Heads of Ayr Holiday Camp, utilised in World War Two as a naval training camp named HMS Scotia. Such was the confusion caused by this nautical prefix, during the conflict Nazi propagandists professed to have sunk ‘her’.

Through the summer months, Glaswegians and those from further afield descended on Ayr in their thousands. Sunshine, alcohol and the release of tensions built up in the white-hot heat of Clydeside meant that holiday life was not always blissful. TheAyrshire Postfor the third week of 1932 brimmed with typical examples of mischief. As the Glasgow Fair holiday period began on 18 July, Ayr teemed with tourists. All-day drinking destroyed their inhibitions and frustrations from home spilled into rioting on local streets. ThePostdetailed how a party from Coatbridge destroyed their bus from within, and then turned it into a boxing ring on wheels. In the Trades Hotel, a mob stormed a card table and robbed those playing of their winnings. On St John Street, the owner of a billiards hall had his hat pulled over his eyes and was beaten for asking four men to conclude their game. When the police arrived, an armed battle with cue-wielding players erupted. At the Esplanade, two men were arrested for brawling. In their defence, they contended the fight had been waged in a friendly spirit. In all, that day Bailie Ross of the magistrates’ court presided over 13 different cases. It was a long way from nimble fingers and the Ayr Reading Room.

Short of a violent brawl to enjoy, I headed back through Wellington Square and past the end of Fort Street, site of the horrific 1876 Templeton fire. This almighty blaze started when a threading machine caught light, and was accelerated as the ‘extincteur’ failed and doused the factory’s wooden floors in flammable oil. The inferno burst through the windows and roared up a spiral staircase, cutting off the 28 female carpet weavers, aged between 11 and 21, who worked in the building’s attic. Factory foreman David Copperauld tried to rescue the women by placing a ladder where the staircase had been. However, as theAyr Advertiserrecorded,

None of them would venture to cross the awful gulf. Terror-stricken and bewildered, they would see equal danger in any alternative, and preferred to remain where they were till the few moments passed away when escape was any longer possible. Copperauld held the ladder till it caught fire; his hands were burnt holding it, and as the flames began to leap higher, the girls closed the attic door, as if to keep them out, and were seen no more. The spectators who had gathered below saw the awful spectacle of girls’ arms waving up through the attic windows, and heard shrieks, many of them by very youthful voices, of the most heartrending description.

After 10 minutes, the waving and shrieking came to an end, an eerie calm providing evidence that the smoke had taken the attic girls’ lives before the fire could.

From Fort Street, I crossed Sandgate and headed along Boswell Park. Opposite a classically grim Royal Mail sorting office was the scuffed exterior of Mecca Bingo, formerly Green’s Playhouse where in 1953 a troubled Frank Sinatra played two sparsely attended shows. In the High Street, Saturday afternoon shopping couples argued outside chain shops and empty outlets, while William Wallace surveyed the scene from his tower and wondered if it had all been worthwhile. I slipped down the orderly cobbles of Newmarket Street and out onto Sandgate, a wide and varied boulevard containing the pale crooked beauty of Lady Cathcart’s House and a dedicated lawn bowling emporium. The impressive Town Hall was midway through hosting its ‘Organist Entertains’ season, 126 years after the keyboards played Oscar Wilde onto the stage there.

Wilde’s 1883 appearance in Ayr invited extensive media coverage. With the writer’s fame at a peak on both sides of the Atlantic, the Town Hall was packed to capacity for a lecture on ‘The House Beautiful’. Both theAyr Observerand theAyr Advertiserdescribed his image at length. ‘With regard to the lecturer’s personal appearance,’ noted theObserver,

it may be stated that it is rendered somewhat remarkable from a mass of dark, well-curled hair surrounding a somewhat effeminate face of a sallow complexion. With one or two exceptions in matters of detail, the lecturer was attired very much like ordinary mortals.

TheAdvertiser, meanwhile, carried a subtly critical, even sarcastic tone:

His somewhat heavy, though well-chiselled, features have been made familiar by engravings and caricatures; but his hair, instead of hanging down upon his shoulders, as it was wont to do, is in a frowsy brown mass coming down upon the brow, somewhat after the style adopted by some ‘girls of the period’. He was in evening dress coat of the cut that was in vogue half a century ago.

Wilde preached to the people of Ayr on the philosophy of decorating a room, and offered practical tips in creating a perfect home. As has often been said, he was truly the Carol Smillie of his day.

Taking in the elegant arches of the Old Bridge from the vantage of the New, I headed towards Somerset Park via Wallacetown. Just over a century ago, crossing the River Ayr meant crossing into a very different place. Far away from the prosperity of the West End and its gentrified visitors, Wallacetown was a district of intense deprivation in which Irish immigrants were abandoned to live in squalor. Dr HJ Littlejohn, a medical officer with the Board of Supervision, reported in 1878 how the area was

inhabited by a low class of the population... the houses were of poor description… this at one time outlying country district still maintains the characteristics of a dirty village… The cottages have manure in all directions in their back courts, ill-kept piggeries abound, and privy accommodation is either totally awanting or of the most offensive description. Ayr itself is one of our cleanest Scotch towns and such adjuncts as Wallacetown must be made to conform to the usages.

This was hidden Ayr, a town where, as Dr Littlejohn wrote, ‘all attractions can be seen and enjoyed without the poverty and wretchedness of many of its poorer inhabitants being obtruded upon the visitor.’ Wallacetown today is a centrally-planned area of low-rise flats, architecturally bland but spacious, neat and tidy enough to suggest the double life of Ayr is not as pronounced as it once was.

Behind Wallacetown, the rusty floodlight pylons of Somerset Park beckoned me. It was August, time for real life to begin again.

* * *

Crossing the railway bridge from Wallacetown, the mossy canopies of Somerset Park come into view. The authenticity of the ground is immediately obvious. For over one hundred years, people have trekked over this bridge to stand under Somerset’s corrugated roofs in pursuit of diversion and the chance to shout at grown men.

The origins of football in Ayr go further than Somerset Park and back to the Low Green. While Ayr Thistle were the first to play organised matches there, it had long played host to mass kickabouts of the flat caps for goalposts variety. From the 1860s, this raw interest in the game prompted the formation of several local clubs, most notably Ayr FC and Ayr Parkhouse. It was an era in which, so the legend goes, pigeons carried half-time scores from football grounds to nearby towns, and one of team names that appear to have been dreamt up by the Romantic Poets; other local sides included Glenbuck Cherrypickers, The Early Risers of Troon, Dailly Pan Rattlers, Trabboch Heroes, Ayr Bonnie Doon and Mossblown Strollers.

As if trying to prove their masculinity in the face of such decadence, players and fans indulged in regular bouts of violence. In 1890, Hearts travelled west to face Ayr FC in a Scottish Cup tie. Keeping goal for the home side that day was Fullarton Steel, an eccentric prone to entertaining the crowd by making saves with his feet alone. After Steel made one such stop, opposition forward Davie Russell thrust a boot into his chest. A scrap broke out between the two sides, and home fans jumped the rope around the side of the pitch to launch an attack on Russell. Pursued by this mob, the petrified forward sprinted for the safety of the main stand and jumped in. He then borrowed a coat and hat, and watched the rest of the match incognito as a petrified spectator.

The intensity with which Ayr FC fans followed their team did not falter down the years. Another Scottish Cup game, this time away at Peebles in 1909, saw them flock south by special train in considerable numbers. TheAyr Observerset the scene:

The good people of Peebles must have thought their ancient town invaded as they saw the force, three hundred strong, making its way under a banner, which, by its torn appearance, might have done duty at Flodden, up the station road and across the bridge over the Tweed into the town.

Though the fervency of football fans in Ayr was undoubted, their numbers remained modest. It soon became clear that the town was simply not large enough to support two Scottish League sides; if local football was to prosper, Ayr FC and Parkhouse would have to merge. After talks between directors of the two clubs during the spring of the Peebles match ended in gentle mud-slinging (‘the members feel very annoyed,’ wrote Ayr FC secretary H Murray in the local press), hopes of an amalgamation dwindled. Only a mediocre 1909/10 season for both pushed Ayr’s footballing bureaucrats back around the negotiating table, and in May 1910 they announced the creation of Ayr United Football Club.

The new club found rapid success, winning the second tier title two years after their establishment, only to be denied promotion in a brazen act of protectionism by the Scottish League. Unperturbed, they cantered to the championship again the following term, 1912/13, and were accepted for promotion to Division One. Along the way, ‘The Honest Men’ played their biggest game to date, another cup tie, this time against Airdrieonians. A record crowd of 9,000 clustered at Somerset Park to see the home side defeated 2–0, and the obligingly partisanAyr Advertiserclaimed that ‘No unbiased spectator could deny that a fair result of the game would have been a 2–1 victory for Ayr. It was the fastest and most exciting all through that has been witnessed for years.’ More negatively, TheAdvertiser’s reporter bemoaned working conditions, writing how

The pressmen were shunted from under cover to the top of the open stand, which possibly enabled the directors to harvest a few more shillings but which would have rendered the position of the pencillers untenable had the threatened rain put in an appearance. As it was, the breeze played many pranks with ‘copy’.

At the start of 1914, Ayr were becoming a fixture in Division One. By the end of it, troops had marched across their pitch under a banner that read ‘A Hearty Welcome To Men From Ayrshire Who Join Us’. An inspection of Ayr shareholders’ annual report for 1915 captures the conflict’s impact:

The continuance of the war has had its effect on the finances of the club. The withdrawal of so many of the club’s ardent and enthusiastic followers, away at their country’s call, reducing the size of the gates and depleting our income. The playing strength of the team has been well maintained and in spite of the financial strain, a credit balance is the result of the year’s workings.

Killed on active service were three United players – J Bellringer, R Copperauld and S Herbertson.

In peacetime, the spectre of horrors past understandably lingered. Where desired, release through football was limited by the conflict’s lasting reach. With a post-war shortage of trains, improvisation became key to following one’s team. When Ayr played Kilmarnock in December 1918, fans took a tram to Prestwick, walked 13 miles to Riccarton and caught further transport to Rugby Park. Appealing to popular memories of the Great War, theAyrshire Postcolourfully illustrated the irritation this journey brought:

The Kaiser has always been famous for the quality of the language he uses when in his high falutin moods, but the floe of ‘flowery’ composition which was heard in the vicinity of Tam’s Brig on Saturday about one o’clock surpasses anything the deposed Hun head was ever father of. The cause of the fiery outburst was the non-materialisation of a certain means of transport to Kilmarnock, which had been promised to a coterie of rabid football enthusiasts.

This devotion to reaching the match is recognisable to supporters today. Similarly, there is something familiar about the Brake Clubs that terrorised towns in the early decades of the last century. The Brake Clubs were, essentially, supporters’ clubs with an eye for brawling. Setting out in horse-drawn wagonettes, and later charabancs, gang members followed their instinct for trouble across Scotland, rioting inside and outside of football grounds. In December 1920, members of the Rangers Brake Club stood among a 12,000-strong crowd at a buoyant Somerset Park. Leading 1–0, all was well with the Gers. In the away end, bugles sounded, rattles clicked and banners were proudly unfurled. Ayr, though, had the temerity to score an equalising goal, and shortly afterwards, when a Rangers player was fouled in front of the away end, and in full view of the Brakes, an air of hostility grew. As theAyr Advertiserrelated under the headline ‘Rowdyism Rampant’,

A section, just immediately behind the Ayr goal, did not relish the idea of their favourites losing a point. Stones, bottles and other missiles, it was alleged, were thrown at some of the Ayr players and the referee had to stop the game and appeal to the police to try and restore order at this particular point.

George Nisbet proves that you can wear a turtleneck jumperand still look hard.

Ayr keeper George Nisbet was struck by stones and Brake Club members attempted to invade the pitch, although, TheAdvertisercontinued, ‘the police had by this time been reinforced and managed to keep the mob in check.’ In the town centre after the game, the Brakes proceeded to go on the rampage. The following Monday in court, burgh prosecutor LC Boyd’s charge sheet reflected their early evening spree. On Fort Street, one John Somerville had turned a car straight into a building. Boyd found him guilty of drink driving. Others were charged with using Rangers flagpoles to attack police officers on the High Street. Over the following days, Boyd dispensed numerous sentences for breaches of the peace ranging from swearing to assault. For Rangers’ next visit, the Brake Club were re-routed to avoid residential areas.

Ayr were to play Rangers frequently in the inter-war years, only spending two seasons outside the top division in that time. Their 1928 Division Two title was inspired by the exploits of the extraordinary Jimmy Smith. A native of Old Kilpatrick village, Smith had arrived at Somerset Park via Dumbarton Harp, Clydebank and the Gers. From the start of the 1927/28 season, the goals flowed – early on, he scored five against Albion, and then two hat-tricks in a fortnight. By Hogmanay, Smith had plundered 35 league goals. In total that season, he scored 66 times, eclipsing the exploits of Dixie Dean and earning himself a place inThe Guinness Book of Records. That summer, Ayr travelled to Scandinavia where they defeated Sweden 3–1. Smith scored two of the goals, and was branded ‘The British Champion’. Ayr had found its golden boy.

It was proving to be something of a halcyon era for mavericks at Somerset Park, yet the next to come along, Hyam Dimmer, is far less well remembered than Smith. Often the tallest man on the pitch, from 1935 inside forward Dimmer used his wiry frame to Ayr’s advantage. He was renowned for gyroscopic contortions, a human magic box of tricks, flicks and pirouettes who revelled in creating laughter on the terraces and bemusement among opponents. As encyclopaedic club historian Duncan Carmichael told me,

The odd thing about Hyam Dimmer was his complexity of motions. He was more interested in entertaining the crowd and making goals for others than in scoring himself. There was a home match coinciding with Students’ Day. Students were dressed up, running about with their collection tins. Dimmer was trying to match them. He had a sense of devilment about him. Not only did he have the temperament to humiliate opposing players, he had the ability to do it.

Dimmer was an enigmatic maestro, as quietly approachable off the field as he was devastatingly extravagant on it. His unusual handle added to the mystique, as Carmichael continued:

‘Hyam’ is something that I don’t understand. The name Hyam is synonymous with showmanship. He was brought up in Scotstoun, which was a rough shipbuilding area, and he’s got a name like Hyam! You can only think his life must have been a misery at school with a name like Hyam. It was his name, it wasn’t an adopted name, it wasn’t a nickname. Such a flamboyant name for a player with a flamboyant style.

Contemporary match reports from theAyr AdvertiserandAyrshire Postdetail that flamboyance. In a September 1936 thrashing of Forfar, ‘though keeping a solemn poker face, he had the crowd in a good humour with his football wizardry and cheeky capers.’ Three months later on Boxing Day, Dimmer confirmed himself as ‘football’s number one entertainer’ in an 8–1 mauling of Montrose. That season, he scored 25 goals and conjured up many more for others as Ayr took the title. From the next term’s opening, a 6–2 victory over Queen’s Park, Dimmer proved his majesty at a higher level. That day, ‘he had the defence running in circles and the crowd laughing.’ Predictably, his devilish artistry invited robust treatment from defenders; against St Mirren, ‘Dimmer tried some of his surrealist stuff on an opposition which did not appreciate art.’ His style could also arouse frustration among teammates and even supporters, goading report card-like opprobrium in the local press:

Hyam started off not too well and created a bad impression by dillydallying in a way which aroused the alternate delight and ire of the spectators. Dimmer is a born footballer but he has a habit of using his feet more than his head – which on occasion has made him more annoying than useful.

Hyam Dimmer, knobbly-kneed magician.

At the outbreak of World War Two Dimmer remained, aged just 22, far from footballing maturity. Military service robbed him of his prime: the Scottish Football Association’s announcement on 4 September 1939 that ‘in view of the government order closing all places of entertainment and outdoor sport, football players’ contracts are automatically cancelled’ ended Dimmer’s top flight career with Ayr. Though his time passed too quickly, this gangly magician had charmed football, his on-field excesses tolerated and even celebrated as a mesmeric trapping of genius.

* * *

When the Scottish League recommenced at the end of World War Two, Ayr United were controversially placed in Division Two and did not win promotion again until 1956. Four years later the club marked its Silver Jubilee optimistically, with an officially-produced booklet entitled