6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

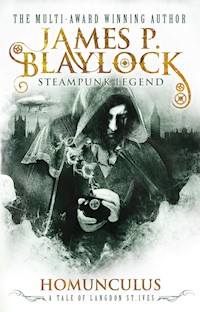

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

A mysterious airship orbits through the foggy skies above Victorian London. Its terrible secrets are sought by many, including: the Royal Society; a fraudulent evangelist; a fiendish vivisectionist; an evil millionaire; and an assorted group led by the scientist and explorer, Professor Langdon St. Ives. Can St. Ives keep the alien homunculus out of the claws of the villainous Ignacio Narbondo?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Also by James P. Blaylock

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue: London 1870

One: The West End

Two: The Trismegistus Club

Three: A Room With a View

Four: Villainies

Five: Shadows on the Wall

Six: Betrayal

Seven: The Blood Pudding

Eight: At the Oceanarium

Nine: Poor Bill Kraken

Ten: Trouble at Harrogate

Eleven: Back to London

Twelve: The Animation of Joanna Southcote

Thirteen: The Royal Academy

Fourteen: Pule Sets Out

Fifteen: Turmoil on Pratlow Street

Sixteen: The Return of Bill Kraken

Seventeen: The Flight of Narbondo

Eighteen: On Wardour Street

Nineteen: On the Heath

Twenty: Birdlip

Epilogue

About the Author

Also Available from Titan Books

ALSO BY JAMES P. BLAYLOCK

AND AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

Lord Kelvin’s Machine

The Aylesford Skull

The Aylesford Skull Limited Edition

TITAN BOOKS

Homunculus

Print edition ISBN: 9780857689825

E-book edition ISBN: 9780857689832

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: February 2013

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

James P. Blaylock asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Copyright © 1986, 2013 James P. Blaylock

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at [email protected] or write to us at Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website.

WWW.TITANBOOKS.COM

To Viki

And, this time,

To Tim Powers, for scores of good ideas, unending friendship, and good cheer.

To Serena Powers, who deserves more than this humble volume. William Hazlitt sends his apologies to Jenny Bunn.

“What a delicate speculation it is, after drinking whole goblets of tea, and letting the fumes ascend into the brain, to sit considering what we shall have for supper—eggs and a rasher, a rabbit smothered in onions, or an excellent veal cutlet! Sancho in such a situation once fixed upon cow-heel; and his choice, though he could not help it, is not to be disparaged.”

WILLIAM HAZLITT

“On Going a Journey”

“I should wish to quote more, for though we are mighty fine fellows nowadays, we cannot write like Hazlitt. And, talking of that, Hazlitt’s essays would be a capital pocketbook on such a journey; so would a volume of Ashbless poems; and for Tristram Shandy I can pledge a fair experience.”

ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON

“Walking Tours”

PROLOGUE

LONDON 1870

Above the St. George’s Channel clouds thick as shorn wool arched like a bent bow from Cardigan Bay round Strumble Head and Milford Haven, and hid the stars from Swansea and Cardiff. Beyond Bristol they grew scanty and scattered and were blown along a heavenly avenue that dropped down the sky toward the shadows of the Cotswold Hills and the rise of the River Thames, then away east toward Oxford and Maidenhead and London. Stars winked and vanished and the new moon slanted thin and silver below them, the billowed crescent sail of a dark ship, swept to windward of stellar islands on deep, sidereal tides.

And in the wake of the moon floated an oval shadow, tossed by the whims of wind, and canting southeast from Iceland across the North Atlantic, falling gradually toward Greater London.

Two hours yet before dawn, the wind blew in fits above Chelsea and the sky was clear as bottled water, the clouds well to the west and east over the invisible horizon. Leaves and dust and bits of paper whirled through the darkness, across Battersea Park and the pleasure boats serried along the Chelsea shore, round the tower of St. Luke’s and into darkness. The wind, ignored by most of the sleeping city, was cursed at by a hunchbacked figure who drove a dogcart down the Chelsea Embankment toward Pimlico, a shabby vehicle with a tarpaulin tied across a humped and unnatural load.

He looked back over his shoulder. The end of the canvas flapped in the wind. It wouldn’t do to have it fly loose, but time was precious. The city was stirring. The carts of ambitious costermongers and greengrocers already clattered along to market, and silent oyster boats sailed out of Chelsea Reach toward Billingsgate.

The man reined in his horse, clambered down onto the stones, and lashed the canvas tight. A putrid stench blew out from under it. The wind was from the northeast, at his back. Such was the price of science. He put a foot on the running board and then stopped in sudden dread, staring at an open-mouthed and wide-eyed man standing on the embankment ahead with a pushcart full of rags. The hunchback gave him a dark look, most of it lost in the night. But the ragpicker wasn’t peering at him, he was staring skyward where, shadowing the tip of the moon overhead, hovered the dim silhouette of a great dirigible, a ribby gondola swinging beneath. Rhythmic humming filled the air, barely audible but utterly pervasive, as if it echoed off the dome of the night sky.

The hunchback leaped atop the seat, whipped his startled horse, and burst at a run past the stupefied ragpicker, knocking his barrow to bits against a stone abutment. With the wind and the hum of the blimp’s propellers driving him along, the hunchback scoured round the swerve of Nine Elms Reach and disappeared into Westminster, the blimp drifting lower overhead, swinging in toward the West End.

Along Jermyn Street the houses were dark and the alleys empty. The wind banged at loose shutters and unlatched doors and battered the new wooden sign that hung before Captain Powers’ Pipe Shop, yanking it loose finally in the early morning gray and throwing it end over end down Spode Street. The only light other than the dim glow of a pair of gaslamps shone from an attic window opposite, a window which, if seen from the interior of Captain Powers’ shop, would have betrayed the existence of what appeared to be a prehistoric bird sporting the ridiculous rubber beak of a leering pterodactyl. Beyond it a spectacled face, half frowning, examined a rubber ape with apparent dissatisfaction. It wasn’t the ape, however, that disturbed him; it was the wind. Something about the wind made him edgy, restless. There was too much noise on it, and the noises seemed to him to be portentous. Just when the cries of the windy night receded into regularity and faded from notice, some rustling thing – a leafy branch broken from a camphor tree in St. James’ Square or a careering crumple of greasy newspaper – brushed at the windowpane, causing him to leap in sudden dread in spite of himself. It was too early to go to bed; the sun would chase him there soon enough. He stepped across to the window, threw open the casement, and shoved his head out into the night. There was something on the wind – the dry rustle of insect wings, the hum of bees… He couldn’t quite name it. He glanced up at the starry sky, marveling at the absence of fog and at the ivory moon that hung in the heavens like a coathook, bright enough, despite its size, so that the ghosts of chimney pots and gables floated over the street. Closing the casement, he turned to his bench and the disassembled shell of a tiny engine, unaware of the fading of the insect hum and of the oval shadow that passed along on the pavement below, creeping toward Covent Garden.

It wasn’t yet four, but costermongers of all persuasions clustered at the market, pushing and shoving among greengrocers, ragpickers, beggars, missionaries, and cats. Carts and wagons full of vegetables were crammed in together along three sides of the square, heaped with onions and cabbages, peas and celery. On the west side of the square sat boxes and baskets of potted plants and flowers – roses, verbena, heliotrope and fuchsia – all of it emitting a fragrance which momentarily called up memories, suspicions of places at odds with the clatter and throng that stretched away down Bow Street and Maiden Lane, lost almost at once among a hundred conflicting odors. Donkey carts and barrows choked the five streets leading away, and flower girls with bundles of sweet briar competed with apple women, shouting among the carts, the entire market flickering in the light of gaslamps and of a thousand candles thrust into potatoes and bottles and melted heaps of wax atop brake-locked cartwheels and low window sills, yellow light dancing and dying and flaring again in the wind.

A tall and age-ravaged missionary advertising himself as Shiloh, the Son of God, stood shivering in sackcloth and ashes, shouting admonitory phrases every few seconds as if it helped him keep warm. He thrust tracts into random faces, as oblivious to the curses and cuffs he was met with as the throng around him was oblivious to his jabber about apocalypse.

The moon, yellow and small, was sinking over Waterloo, and the stars were one by one winking out when the dirigible sailed above the market, then swept briefly out over the Victoria Embankment on its way toward Billingsgate and Petticoat Lane. For a few brief seconds, as the cry went round and thousands of faces peered skyward, the slat-sided gondola that swayed beneath the blimp was illuminated against the dying moon and the glow it cast on the clouds. A creaking and shuddering reached them on the wind, mingled with the hum of spinning propellers. Within the gondola, looking for all the world as if he were piloting the moon itself, was a rigid figure in a cocked hat, gripping the wheel, his legs planted widely as if set to counter an ocean swell. The wind tore at his tattered coat, whipping it out behind him and revealing the dark curve of a ribcage, empty of flesh, ivory moonlight glowing in the crescents of air between the bones. His wrists were manacled to the wheel, which itself was lashed to a strut between two glassless windows.

The gondola righted itself, the moon vanished beyond rooftops, and the dirigible had passed, humming inexorably along toward east London. For the missionary, the issuance of the blimp was an omen, the handwriting on the wall, an even surer sign of coming doom than would have been the appearance of a comet. Business picked up considerably, a round dozen converts having been reaped by the time the sun hoisted itself into the eastern sky.

It was with the dawn that the blimp was sighted over Billingsgate. The weathered gondola creaked in the wind like the hull of a ship tossing on slow swells, and its weird occupant, secured to the wooden shell of his strange swaying aerie like a barnacle to a wave-washed rock, stared sightlessly down on fishmongers’ carts and bummarees and creeping handbarrows filled with baskets of shellfish and eels, the wind whirling the smell of it all east down Lower Thames Street, bathing the Custom House and the Tower in the odor of seaweed and salt spray and tidal flats. A squid seller, plucking off his cap and squinting into the dawn, shook his head sadly at the blimp’s passing, touched two fingers to his forehead as if to salute the strange pilot, and turned back to hawking and rubbery, doleful-eyed occupants of his basket, three to the penny.

Petticoat Lane was far too active to much acknowledge the strange craft, which, illuminated by the sun now rather than the reflected light of the new moon, had lost something of its mystery and portent. Heads turned, people pointed, but the only man to take to his heels and run was a tweed-coated man of science. He had been haggling with a seller of gyroscopes and abandoned shoes about the coster’s supposed knowledge of a crystal egg, spirited away from a curiosity shop near Seven Dials and rumored to be a window through which, if the egg were held just so in the sunlight, an observer with the right sort of eyesight could behold a butterfly-haunted landscape on the edges of a Martian city of pink stone, rising above a broad grassy lawn and winding placid canals. The gyroscope seller had shrugged. He could do little to help. To be sure, he’d heard rumors of its appearance somewhere in the West End, sold and resold for fabulous sums. Had the guv’nor that sort of sum? And a man of science needed a good gyroscope, after all, to demonstrate and study the laws of gravity, stability, balance, and spin. But Langdon St. Ives had shaken his head. He required no gyroscope; and yes, he did have certain sums, some little bit of which he’d gladly part with for real knowledge.

But the hum of the blimp and the shouts of the crowd brought him up short then, and in a trice he was pounding down Middlesex Street shouting for a hansom cab, and then craning his neck to peer up out of the cab window as it rattled away east, following the slow wake of the blimp out East India Dock Road, losing it finally as it rose on an updraft and was swallowed by a white bank of clouds that fell away toward Gravesend.

ONE

THE WEST END

On April 4 of the year 1875 – thirty-four centuries to the day since Elijah’s flight away to the stars in the supposed flaming chariot, and well over eighty years after the questionable pronouncement that Joanna Southcote suffered from dropsy rather than from the immaculate conception of the new messiah – Langdon St. Ives stood in the rainy night in Leicester Square and tried without success to light a damp cigar. He looked away up Charing Cross Road, squinting under the brim of a soggy felt hat and watching for the approach of – someone. He wasn’t sure who. He felt foolish in the top shoes and striped trousers he’d been obliged to wear to a dinner with the secretary of the Royal Academy of Sciences. In his own laboratory in Harrogate he wasn’t required to posture about in stylish clothes. The cigar was beginning to become irritating, but it was the only one he had, and he was damned if he’d let it get the best of him. He alternately cursed the cigar and the drizzle. This last had been falling – hovering, rather – for hours, and it confounded St. Ives’ wish that it either rain outright or give up the pretense and go home.

There was no room in the world of science for mediocrity, for half measures, for wet cigars. He finally pitched it over his shoulder into an alley, patted his overcoat to see if the packet beneath was still there, and had a look at his pocket watch. It was just shy of nine o’clock. The crumpled message in his hand, neatly blocked out in handwriting that smacked of the draftsman, promised a rendezvous at eight-thirty.

“Thank you, sir,” came a startling voice from behind him. “But I don’t smoke. Haven’t in years.” St. Ives spun round, nearly knocking into a gentleman under a newspaper who hurried along the cobbles. But it wasn’t he who had spoken. Beyond, slouching out of the mouth of an alley, was a bent man with a frazzle of damp hair protruding from the perimeter of a wrecked Leibnitz cap. His extended hand held St. Ives’ discarded cigar as if it were a fountain pen. “Makes me bilious,” he was saying. “Vapors, it is. They say it’s a thing a man gets used to, like shellfish or tripe. But they’re wrong about it. Leastways they’re wrong when it comes to old Bill Kraken. But you’ve got a dead good aim, sir, if I do say so myself. Struck me square in the chest. Had it been a snake or a newt, I’d have been a sorry Kraken. But it weren’t. It were a cigar.”

“Kraken!” cried St. Ives, genuinely astonished and taking the proffered cigar. “Owlesby’s Kraken is it?”

“The very one, sir. It’s been a while” And with that, Kraken peered behind him down the alley, the mysteries of which were hidden in impenetrable darkness and mist.

In Kraken’s left hand was an oval pot with a swing handle, the pot swaddled in a length of cloth, as if Kraken carried the head of a Hindu. Around his neck was a small closed basket, which, St. Ives guessed, held salt, pepper, and vinegar. “A pea man, are you now?” asked St. Ives, eyeing the pot. Standing in the night air had made him ravenous.

“Aye, sir,” replied Kraken, shaking his head. “By night I am, usually up around Cheapside and Leadenhall. I’d offer you a pod, sir, but they’ve gone stone cold in the walk.”

A door banged shut somewhere up the alley behind them, and Kraken cupped a hand to his ear to listen. There was another bang followed close on by a clap of thunder. People hurried past, huddled and scampering for cover as a wash of rain, granting St. Ives’ wish, swept across the square. It was a despicable night, St. Ives decided. Some hot peas would have been nice. He nodded at Kraken and the two men hunched away, sloshing through puddles and rills and into the door of the Old Shades, just as the sky seemed to crack in half like a China plate and drop an ocean of rain in one enormous sheet. They stood in the doorway and watched.

“They say it rains like that every day down on the equator,” said Kraken, pulling off his cap.

“Do they?” St. Ives hung his coat on a hook and unwound his muffler. “Any place special on the equator?”

“Along the whole bit of it,” said Kraken. “It’s a sort of belt, you see, that girds us round. Holds the whole heap together, if you follow me. It’s complicated. We’re spinning like a top, you know.”

“That’s right,” said St. Ives, peering through the tobacco cloud toward the bar, where a fat man poked bangers with a fork. Lazy smoke curled up from the sausages and mingled with that of dozens of pipes and cigars. St. Ives was faint. Nothing sounded as good to him as bangers. Damn pea pods. He’d sell his soul for a banger, sell his spacecraft even, sitting four-fifths built in Harrogate.

“Now the earth ain’t nothing but bits and pieces, you know, shoved in together.” Kraken followed St. Ives along a trail of sausage smoke toward the bar, crossing his arms in front of his pot. “And think of what would come of it if you just set the whole mess aspin. Like a top, you know, as I said.”

“Confusion” said St. Ives. “Utter confusion”

“That’s the very thing. It would all go to smash. Fly to bits. Straightaway. Mountains would sail off. Oceans would disappear. Fish and such would shoot away into the sky like Chinese rockets. And what of you and me? What of us?”

“Bangers and mash for my friend and me,” said St. Ives to the publican, who looked at Kraken’s peapot with disfavor. “And two pints of Newcastle.” The man’s face was enormous, like the moon.

“What of us, is what I want to know. It’s a little-known fact.”

“What is?” asked St. Ives, watching the moon-faced man spearing up bangers, slowly and methodically with pudgy little fingers, almost sausages themselves.

“It’s a little-known fact that the equator, you see, is a belt – not cowhide, mind you, but what the doctor called elemental twines. Them, with the latitudes, is what binds this earth of ours. It isn’t as tight as it might be, though, which is good because of averting suffocation. The tides show this – thank you, sir; God bless you – when they go heaving off east and west, running up against these belts, so to speak. And lucky it is for us, sir, as I said, or the ocean would just slide off into the heavens. By God, sir, this is first-rate bangers, isn’t it?”

St. Ives nodded, licking grease from his fingertips. He washed a mouthful of the dark sausage down with a draught of ale. “Got all this from Owlesby, did you?”

“Only bits, sir. I do some reading on my own. The lesser-known works, mostly.”

“Whose?”

“Oh, I ain’t particular, sir. Not Bill Kraken. All books is good books. And ideas, if you follow me, facts that is, are like beans in a bottle. There’s only so many of them. The earth ain’t but so many miles across. I aim to have a taste of them all, and science is where I launched out, so to speak.”

“That’s where I launched out too,” said St. Ives. “I’ll just have another pint. Join me?”

Kraken yanked a faceless pocket watch out of his coat and squinted at it before nodding. St. Ives winked and pushed away once more toward the bar. It was an hour yet before closing. A tramp in rags sidled from table to table, uncovering at each the stump of a recently severed thumb. A man in evening clothes lay on the floor, straight out on his side, his nose pressed against a wall, and three stools, occupied by his sodden young friends, propped him up there as if he were a corpse long gone in rigor mortis. There was an even cacophony of sounds, of laughter and clanking dishes and innumerable conversations punctuated at intervals by a loud, tubercular cough. More floor was covered by shoe soles and table legs than was bare, and that which was left over was scattered with sawdust and newspaper and scraps of food. St. Ives mashed the end of a banger beneath his heel as he edged past two tables full of singing men – seafaring men from the look of them.

Kraken appeared to be half asleep when minutes later St. Ives set the two pint glasses on the tabletop. The pleasant and solid clank of the full glasses seemed to revive him. Kraken set his peapot between his feet. “It’s been a while, sir, hasn’t it?”

“Fourteen years, is it?”

“Fifteen, sir. A month before the tragedy, it was. You wasn’t much older’n a bug, if I ain’t out of line to say so.” He paused to drink off half the pint. “Them was troublesome times, sir. Troublesome times. I ain’t told a soul about most of it. Can’t. I’ve cheated myself of the hereafter; I can’t afford Newgate”

“Surely nothing as bad as that…” began St. Ives, but he was cut short by Kraken, who waved broadly and shook his head, falling momentarily silent.

“There was the business of the carp,” he said, looking over his shoulder as if he feared that a constable might at that moment be slipping up behind. “You don’t remember it. But it was in the Times, and Scotland Yard even had a go at it. And come close, too, by God! There’s a little what-do-you-call-it, a gland or something, full of elixir. I drove the wagon. Dead of night in midsummer, and hot as a pistol barrel. We got out of the aquarium with around a half-dozen, long as your arm, and Sebastian cut the beggars up not fifty feet down Baker Street, on the run but neat as a pin. We gave the carps to a beggar woman on Old Pye, and she sold the lot at Billingsgate. So good come of it in the end.

“But the carp affair was the least of it. I’m ashamed to say more. And it wouldn’t be right to let on that Sebastian was behind the worst. Not by a sea mile. It was the other one. I’ve seen him more than once over the fence at Westminster Cemetery, and late at night too, him in a dogcart on the road and me and Tooey Short with spades in our hand. Tooey died in Horsemonger Lane Gaol, screaming mad, half his face scaled like a fish”

Kraken shuddered and drained his glass, falling silent and staring into the dregs as if he’d said enough – too much, perhaps.

“It was a loss when Sebastian died,” said St. Ives. “I’d give something to know what became of his notebooks, let alone the rest of it”

Kraken blew his nose into his hand. Then he picked up his glass and held it up toward a gaslamp as if contemplating its empty state. St. Ives rose and set out after another round. The moon-faced publican poured two new pints, stopping in between to scoop up mashed potatoes with a blackened banger and shove it home, screwing up his face and smacking his lips. St. Ives winced. An hour earlier a hot banger had seemed paradisaical, but four bangers later there was nothing more ghastly to contemplate. He carried the two glasses back to the table, musing on the mutability of appetite and noting through the open door that the rain had let off.

Kraken met him with a look of anticipation, and almost at once did way with half the ale, wiping the foam from his mouth with the sleeve of his shirt. St. Ives waited.

“No, sir,” said Kraken finally. “It wasn’t the notebooks I’m sorry for, I can tell you.” Then he stopped.

“It wasn’t?” asked St. Ives, curious.

“No, sir. Not the bleeding papers. Damn the papers. They’re writ in blood. Every one. Good riddance, says I.”

St. Ives nodded expansively, humoring him.

Kraken hunched over the table, waggling a finger at St. Ives, the little basket of condiments on his neck swaying beneath his face like the gondola of a half-deflated balloon. “It was that damn thing,” whispered Kraken, “what I’d have killed.”

“Thing?” St. Ives hunched forward himself.

“The thing in the box. I seen it lift the corpse of a dog off the floor and dance it on the ceiling. And there were more to it than that.” Kraken spoke so low that St. Ives could barely hear him above the din. “Them bodies me and Tooey Short brought in. There was more than one of them as walked out on his own legs.” Kraken paused for effect and sucked down the last half inch of ale, clunking the glass back down onto the oaken tabletop. “No, sir. I don’t rue no papers. And if they’d asked me, I’d ’a’ told them Nell was innocent as a China doll. I loved the young master, and I cry to think he left a baby son behind him, but by God the whole business wasn’t natural, was it? And the filthy shame of it is that Nell didn’t plug that damned doctor after she put one through her brother. That’s what I regret, in a nut.”

Kraken made as if to stand up, his speechifying over. But St. Ives, although shaken by bits of Kraken’s tale, held his hand up to stop his leaving. “I have a note from Captain Powers,” said St. Ives, proffering the crumpled missive to Kraken, “asking me to meet a man in Leicester Square at eight-thirty.”

Kraken blinked at him a moment, then peered over his shoulder toward the door and squinted round the pub, cocking an ear. “Right ho,” he said, sitting back down. He bent toward St. Ives once again. “I ran into the Captain’s man, up in Covent Garden, at the market it was, three days back. And he mentioned the…” Kraken paused and winked voluminously at St. Ives.

“The machine?”

“Aye. That’s the ticket. The machine. Now I don’t claim to know where it is, you see, but I’ve heard tell of it. So the Captain put me onto you, as it were, and said that the two of us might be in a way to do business.”

St. Ives nodded, pulse quickening. He patted his pockets absentmindedly and found a cigar. “Heard tell of it?” He struck a match and held it to the cigar end, puffing sharply. “From whom?”

“Kelso Drake,” whispered Kraken. “Almost a month ago, it was. Maybe six weeks.”

St. Ives sat back in surprise. “The millionaire?”

“That’s a fact. From his very lips. I worked for him, you see, and overheard more than he intended – more than I wanted. A foul lot, them millionaires. Nothing but corruption. But they’ll reap the bread of sorrow. Amen”

“That they will,” said St. Ives. “But what about the machine – the ship?”

“In a brothel, maybe in the West End. That’s all I know. He owns a dozen. A score. Brothels, I mean to say. There’s nothing foul he don’t have a hand in. He owns a soap factory out in Chingford. I can’t tell you what it is they make soap out of. You’d go mad.”

“A brothel that might be in the West End. That’s all?”

“Every bit of it.”

St. Ives studied the revelation. It wasn’t worth much. Maybe nothing at all. “Still working for Drake?” he asked hopefully.

Kraken shook his head. “Got the sack. He was afraid of me. I wasn’t like the rest.” He sat up straight, giving St. Ives a stout look. “But I’m not above doing a bit of business among friends, am I? No, sir. I’m not. Not a bit of it.” He watched St. Ives, who was lost in thought. “Not Bill Kraken. No, sir. When I set out to do a man a favor, across town, through the rain, mind you, why it’s, ‘keep your nose in front of your face. Let it rain!’ That’s my motto when I’m setting out on a job like this one.”

St. Ives came to himself and translated Kraken’s carrying on. He handed across two pound notes and shook his hand. “You’ve done me a service, my man. If this pans out there’ll be more in it for you. Come along to the Captain’s shop on Jermyn Street Thursday evening. There’ll be a few of us meeting. If you can round up more information, you won’t find me miserly.”

“Aye, sir,” said Kraken, rising and fetching up his peapot. He secured the cloths and tied them neatly about the lip of the pot. “I’ll be there.” He folded the two notes and slipped them into his shoe, then turned without another word and hurried out.

St. Ives’ cigar wouldn’t stay lit. He looked hard at it for a moment before recognizing it as the damp thing he’d pitched at Kraken an hour and a half earlier. It seemed to be following him around. The man without the thumb loomed in toward him. St. Ives handed him a shilling and the cigar, found his coat on the rack, checked the inside pocket for his parcel – actually a sheaf of rolled paper – and set out into the night.

Powers’ Pipe and Tobacco Shop lay at the corner of Jermyn and Spode, with long, mullioned windows along both the south and east walls so that a man – Captain Powers, for instance – might sit in the Morris chair behind the counter and, by rotating his head a few degrees, have a view of those coming and going along either street. On the night of the fourth of April, though, seeing much of anything through the utter darkness of the clouded and rainy night was unlikely. The thin glow cast by the two visible gaslamps, both on Jermyn Street, was negligible. And the light that shone from lit windows here and there along the street seemed to have an antipathy to flight, and hovered round its sources wary of the damp night.

Captain Powers would hear the sound of approaching feet on the pavement long before the traveler would appear in one of the two yellow circles of illuminated pavement, then disappear abruptly into the night, the footsteps clop-clopping away into silence.

The houses across the street were inhabited by the genteel, many of whom wandered into the pipe shop for a pouch of tobacco or a cigar. It would have been lean times for the Captain, however, if it hadn’t been for his pension. He’d been at sea since he was twelve and had lost his right leg in a skirmish fifty miles below Alexandria, when his sloop sank in the Nile, blown to bits by desert thieves. He had saved a single tusk of a fortune in ivory, and twenty years later William Keeble the toymaker had made him a leg of it, the best by far of any he’d worn. Not only did it fit without taking the skin off that little bit of leg he had left, but it was hollow and held a pint of liquor and two ounces of tobacco. In a pinch he could smoke the entire leg, could press a button at the tip and manipulate a hidden plate, the size of a half crown, which would slide back to reveal the bowl of a pipe. A tube ran up the inside of his pantleg and coat, and he could walk and smoke simultaneously. The Captain had only done so once, largely because of a sort of odd fascination with the idea of Keeble’s having built it. The bewildered stares of passersby, however, had seemed to argue against the wisdom of revealing in public the wonderful nature of the thing. Captain Powers, grizzled from sea weather and stoic from thirty years of discipline before the mast, was a conservative at heart. Dignity was his byword. But friendship precluded him from letting on to Keeble that he had no real desire to be seen smoking a peg leg.

Keeble’s house, in fact, sat opposite Powers’ store. The Captain looked across the top of his companion’s head at the lamp burning in the attic shop. Below was another room alight – the bedroom of Jack Owlesby; and on the left yet another, the bedroom, quite likely, either of Winnifred – Keeble’s wife – or of Dorothy, the Keeble daughter, home for a fortnight now from finishing school.

His companion cleared his throat as if about to speak, so Captain Powers let his gaze fall from the window to his friend’s face. It had the unmistakable look of nobility to it, of royalty, but it was the face of Theophilus Godall of the Bohemian Cigar Divan in Rupert Street, Soho, a face that at that moment was drawing on an old meerschaum pipe. Carved on either side of the bowl was the coat of arms of the royal family of Bohemia, a house long since scattered and flown from a fallen country. The pipe had had, no doubt, a vast and peculiar history before passing into the hands of Godall, and who knew what sort of adventures had befallen it since?

“I was with Colonel Geraldine,” Godall was saying, “in Holborn. Incognito. It was late and the evening had proven fallow. All we’d accomplished was to have spent too much good money on bad champagne. We’d had a pointless discussion with a fellow who had a promising story about a suicidal herb merchant on Vauxhall Bridge Road. But the fellow – the second fellow, that is, the herb merchant – turned out to be already dead. Hanged himself these six months past with his own gaiters, and the first fellow turned out to be uninteresting. I wish I could say he meant well, but what he meant was to drink our champagne.

“Before he left, though, in came two of the most extraordinary men. Obviously bound for the workhouse but neither had any color to him. They had the skin of frog bellies. And they had no notion of where they were. Not the foggiest. They had a sort of dazed look about them, as if they’d been drugged, you might say. In fact that’s what I thought straightaway. Geraldine spoke to the larger of the two, but the man didn’t respond. Looked at him in perfect silence. Not insubordinately, mind you. There was none of that. There was simply no hint of real consciousness.”

The Captain shook his head and tapped the ashes of his pipe into a brass bowl. He looked at the clock under the counter – nearly ten-thirty. The rain had slackened. He could see none at all falling across the illuminated glass of the streetlamp. Footsteps approached slowly, drawing up along Jermyn Street. They stopped altogether. Captain Powers winked at Theophilus Godall, who nodded slightly. The footsteps resumed, angling away across the road toward Keeble’s house. It was just possible that it was Langdon St. Ives, come round to Keeble’s to discuss his oxygenator box. But no, St. Ives would have stopped in if he’d seen a light. He’d have spoken to Kraken by now and be full of alien starships. This was someone else.

A hunched shadow appeared on the pavement opposite – the shadow of a hunchback, to be more exact – and hurried past the gaslamp into darkness, but the Captain was certain that he’d stopped beyond it. He had for five nights running. “There’s your man across the road,” said the Captain to Godall.

“Are you certain of it?”

“Aye. The hunchback. It’s him all right. He’ll hang round till I switch out the lights.”

Godall nodded and resumed his story. “So Geraldine and I followed the two, halfway across town into Limehouse where they went into a pub called the Blood Pudding. We stayed long enough to see that it was full of such men. The two of us stood out like hippopotami. But I can’t say we were noticed by any but him” And Godall shrugged back over his shoulder at the street. “He was a hunchback, anyway. And although I’m not familiar with this fellow Narbondo, it could conceivably have been he. He was eating live birds, unless I’m very much mistaken. The sight of it on top of champagne and kippers rather put us off the scent, if you follow me, and I’d have happily forgotten him completely if it weren’t for your having got me onto this business of yours. Is he still there?”

The Captain nodded. He could just see the hunchback’s shadow, still as a bush, cast across a bit of wall.

A new set of steps approached, accompanied by a merry bit of off-key whistling.

“Get your hat!” cried Captain Powers, standing up. He stepped across and turned down the lamp, plunging the room into darkness. There, striding purposefully up toward Keeble’s door carrying his packet of papers was Langdon St. Ives, explorer and inventor.

In an instant the hunchback – Dr. Ignacio Narbondo – had vanished. Theophilus Godall leaped for the door, waved hastily at Captain Powers, and made away into the night, east on Jermyn toward Haymarket. Across the street, William Keeble threw back the door and admitted St. Ives, who squinted wonderingly at the dark, receding figure that had hurried from the suddenly darkened tobacco shop. He shrugged at Keeble. The Captain’s doings were always a mystery. The two of them were swallowed up into the interior of Keeble’s house.

The street was silent and wet, and the smell of rain on pavement hung in the air of the tobacco shop, reminding the Captain briefly of spindrift and fog. But in an instant it was gone, and the thin and tenuous shadow of the sea vanished with it. Captain Powers stood just so, contemplating, a lazy shaving of smoke rising in the darkness above his head. Godall had left his pipe in his haste. He’d be back for it in the morning; there was little doubt of that.

A sudden light knock sounded at the door, and the Captain jumped. He’d expected it, but the night was full of dread and the slow unraveling of plots. He stepped across and pulled open the heavy door, and there in the dim lamplight on the street stood a woman in a hooded cloak. She hurried past him into the room. Captain Powers closed the door.

St. Ives followed William Keeble up three flights of stairs and into the cluttered toyshop. Logs burned in an iron box, vented out into the night through a terra cotta chimney, and the fire was such that the room, although large, was warm and close, almost hot. But it was cheerful, given the night, and the heat served to evaporate some of the rainwater that dripped in past the slates of the roof. A tremendous and alien staghorn fern hung very near the fire, below the leaded window of the gable that led out onto the roof, and a stream of water, nothing more than a dribble, ran in along the edge of the ill-sealed casement and dripped from the sill into the mossy, decayed box that held the fern. Every minute or so, as if the rainwater pooled up until high enough to run out, a little waterfall would burst from the bottom of the planter and fall with the hiss of steam into the firebox.

Darkened roof rafters angled sharply away overhead, stabilized by several great joists that spanned the twenty-foot width of the shop and provided avenues along which tramped any number of mice, hauling bits of debris and working among the timbers like elves. Hanging from the joists were no end of marvels: winged beasts, carved dinosaurs, papier-mâché masks, odd paper kites and wooden rockets, the amazed and lopsided head of a rubber ape, an enormous glass orb filled with countless tiny carven people. The kites, painted with the visages of birds and deep-water fish, had hung among the rafters for years, and were half obscured by cobweb and dust amid the brown stains of dirty rainwater. Great shreds had been chewed away by mice and bugs to build homes among the hanging debris.

The red pine floor, however, was swept clean, and innumerable tools hung over two work benches, unordered but neat, brass and iron glinting dully in the light of a half-dozen wood and glass sconces. Coughing into his sleeve, Keeble cleared a score of mauve seashells and a kaleidoscope from the benchtop, then swept it clean with a horsehair brush, the handle of which was elegantly carved into the form of an elongated frog.

St. Ives admired it aloud.

“Like that do you?” asked Keeble.

“Quite,” admitted St. Ives, an admirer of William Morris’s philosophy concerning beauty and utility.

“Press its nose”

“Pardon me?”

“Its nose,” said Keeble. “Press it. Give it a shove with your fingertip.”

St. Ives dubiously obeyed, and the top of the frog’s head, from nose to mid-spine, slid back into its body, revealing a long, silver tube. Keeble pulled it out, unscrewed a cap at the end, found two glasses wedged in behind a heap of wooden planes, and from the tube poured an equal share of liquor into each. St. Ives was astonished.

“So what have you got?” asked Keeble, draining his glass and hiding it away once again.

“The oxygenator. Finished, I believe. I’m counting on you for the rest. It’s the last of the lot. The rest of the ship is ready. We’ll launch it in May if the weather clears up.” St. Ives unrolled his drawing onto the benchtop, and Keeble leaned over it, peering intently at the lines and figures through startlingly thick glasses.

“Helium, is it?”

“And chlorophyll. Powdered. There’s an intake here and a spray mechanism and filter there. The clockworks sit in the base – a seven-day works should do it, at least for the first flight.” St. Ives sipped at his glass and looked up at Keeble. “Birdlip’s engine: could it be duplicated on this scale?”

Keeble pulled off his glasses and wiped them on a handkerchief. He shrugged. “Perpetual motion is a tricky business, you know – rather like separating an egg from its shell without altering the shape of either, and then suspending the two there, one a quivering, translucent ovoid, the other a seeming solid, side by side. It’s not done in a day. And the whole thing is relative, isn’t it? True perpetual motion is a dream, although a sage named Gustatorius claimed to have produced it alchemically in 1410 in the Balkans, for the purpose of continually turning the back lens of a kaleidoscope. A wonderful idea, but alchemists tend to be frivolous, taken on the whole. Birdlip’s engine, though, is running down. I’m afraid his appearance this spring may be his last.”

St. Ives glanced up sharply. “Are you?”

“Yes indeed. When it passed five years ago it was low, fearfully so, and far to the north of its passing in ’65. So I’ve a suspicion that the engine is declining. The blimp may well drop into the sea, but I rather think it’s tending toward Hampstead where it was launched. There’s a homing element in the engine; that’s what I think. A chance product of its design, not anything I intended”

St. Ives rubbed his chin, unwilling to let Keeble’s revelation push him off his original course. “But can it be miniaturized? Birdlip has been up for fifteen years. In that time I can easily reach Mars, Saturn even, and return.”

“Yes, in a word. Look at this.” Keeble slid open a drawer and pulled out a wooden box. The joints were clearly visible, and the box was painted with symbols that appeared to be Egyptian hieroglyphs – walking birds and amphibians, eyeballs peering out of pyramids – but there was no sign of a hinge or a latch.

It immediately occurred to St. Ives that the box was a tamper-proof bottle of some sort, perhaps a tiny, self-contained still, and that he would be asked to poke the nose of a painted beast in order to reveal an amber pool of Scotch whisky. But Keeble set the box squarely atop the bench, spun it round forty-five degrees or so, and the lid of the box opened on its own.

St. Ives watched as the lid rose and then fell back. From out of the depths of the box rose a strangely authentic-looking miniature cayman alligator, its long, toothed snout opening and shutting rhythmically. Four little birds followed, one at each corner, and the cayman snapped up and devoured the birds one by one, then grinned, rolled its eyes, made a sound like a rusty hinge, and sank into its den. After a ten-second pause, up it rose again, followed by miraculously restored birds, fated to be devoured over and over again into infinity. Keeble shut the lid, rotated the box a few degrees farther along, and smiled at St. Ives. “It’s taken me twelve years to perfect that, but it’s quite as workable now as is Birdlip’s engine. It’s for Jack’s birthday. He’ll be eighteen soon – fifteen years he’s been with us – and he’s the only one, I fear, who sees these things with the right sort of eye.”

“Twelve years it took?” St. Ives was disappointed.

“It could be done more quickly now,” said Keeble, “but it’s fearsomely expensive.” He was silent for a moment while he put the box away in its drawer. “I’ve been approached, in fact, about the device – about the patent, actually.”

“Approached?”

“By Kelso Drake. He seems to have dreams of propelling entire factories with perpetual motion devices. I haven’t any idea how he got onto them in the first place.”

“Kelso Drake!” cried St. Ives. He almost shouted, “Again!” but hesitated at the melodramatic sound of it and the moment passed. It was an odd coincidence, though, to be sure. First Kraken’s suspicion of Drake’s possessing the alien craft, and now this. But there could hardly be a connection. St. Ives pointed at the plans lying on the bench. “How long then, a month?”

“I should think so,” said Keeble. “That should do nicely. How long are you in London?”

“Until this is accomplished. Hasbro stayed on in Harrogate. I’ve got rooms at the Bertasso in Pimlico.”