8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

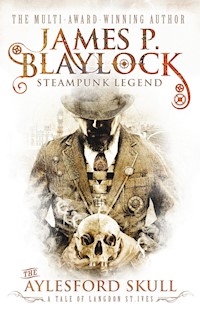

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

It is the summer of 1883 and Professor Langdon St. Ives, brilliant but eccentric scientist and explorer, is at home in Aylesford with his family. A few miles to the north a steam launch has been taken by pirates above Egypt Bay, the crew murdered and pitched overboard. In Aylesford itself a grave is opened and possibly robbed of the skull. The suspected grave robber, the infamous Dr. Ignacio Narbondo, is an old nemesis of Langdon St. Ives. When Dr. Narbondo returns to kidnap his four-year-old son Eddie and then vanishes into the night, St. Ives and his factotum Hasbro race into London in pursuit...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

ALSO BY JAMES P. BLAYLOCK

AND AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

Homunculus

Lord Kelvin’s Machine

The Aylesford Skull Special Edition

TITAN BOOKS

The Aylesford Skull

Print edition ISBN: 9780857689795

E-book edition ISBN: 9780857689818

Special edition ISBN: 9780857689801

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: January 2013

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

James P. Blaylock asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Copyright © 2013 James P. Blaylock

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at [email protected] or write to us at Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website.

WWW.TITANBOOKS.COM

And these are the gems of the Human Soul

The rubies & pearls of a lovesick eye

The countless gold of the akeing heart

The martyrs groan & the lovers sigh

WILLIAM BLAKE

“The Mental Traveler”

For Viki, John, and Danny,

and for

John Berlyne

CONTENTS

Prologue, 1883: River Thames, The Sea Reach

One: Into The Darkness

Two: Home at Last

Three: The Aylesford Skull

Four: The Weir

Five: The Return Of the Dead

Six: The Return Of Bill Kraken

Seven: Hereafter Farm

Eight: Corpse Candle

Nine: A Lane to the Land Of The Dead

Ten: What Duty Requires

Eleven: To London

Twelve: The Queen’s Rest

Thirteen: Lost Objects Found

Fourteen: On The Pilgrims Road

Fifteen: The Goat and Cabbage

Sixteen: Slocumb’s Millinery

Seventeen: Merton’s Rarities

Eighteen: The Rookery

Nineteen: Billson’s Half Toad Inn

Twenty: Mother and Son

Twenty One: Angel Alley

Twenty-Two: The Best-Laid Plans

Twenty-Three: Flaming Syllabub

Twenty-Four: After the Battle

Twenty-Five: Lord Moorgate

Twenty-Six: Shade House

Twenty-Seven: Aloft Over London

Twenty-Eight: The Cipher

Twenty-Nine: Cliffe Village

Thirty: The Barred Window

Thirty One: The Message Arrives

Thirty Two: The Tunnel Beneath the Inn

Thirty-Three: The King Of the Daft

Thirty-Four: Uncle Gilbert’s Encampment

Thirty-Five: Bloody Beefsteak

Thirty-Six: The Burning

Thirty-Seven: Mrs. Marigold

Thirty-Eight: Carried Away

Thirty-Nine: London Arrivals

Forty: Morning

Forty One: The Cathedral Of the Oxford Martyrs

Forty-Two: From The Arched Window

Forty-Three: The Ghost’s Revenge

Forty-Four: The Jam Pot

Acknowledgments

About the Author

PROLOGUE, 1883

RIVER THAMES, THE SEA REACH

The black smoke issuing from the chimney of the steam launch was nearly invisible under the cloudy night sky, although now and then the moon shone through a break in the clouds, illuminating the narrow launch, the streaming smoke, and the dirty canvas canopy that arched over the stern of the thirty-five-foot vessel. The river was empty in the early morning darkness, nothing to be seen ahead, and far behind them the shadow of the distant boat that they’d passed forty minutes back, low in the water, disappearing behind flurries of rain.

The launch wanted very little draft, and now she hugged the marshy Thames shore, running upriver toward Gravesend. The Pilot, Nathaniel Wise, stood at the wheel in the prow, his hat doing little to keep off the rain. Despite his time on the water, he had never learned to swim, and he meant to be as close in to the land as ever he could be if there were trouble, especially on this uncomfortably empty stretch of river. He owed nothing to the man who had hired him, and although the pay was good enough, it wasn’t worth dying for, not by a long chalk.

“Those lights you see,” he said to the dull-witted boy sitting by the furnace, “them’s the lights of the Havens, as we call them, and over there the Chapman Light.” The boy looked around, trying to make out what Wise was talking about. “There on the starboard shore, Billy. Not much farther now and we’ll slant ’round into the Lower Hope, and then it’s ten miles in all to Gravesend. In an hour by the clock you’ll be dry again, with the tide beating against the stern like it is.”

The boy nodded at him, but didn’t speak. Too miserable, perhaps. The wind sprang up now, the rain beat down, and there was thunder downriver. In Gravesend, Wise would collect his percentage and find a warm berth at a handy inn, leaving the unloading of the launch to the four men who huddled in the stern beneath the canvas now, out of the rain and dry, drunk on gin they’d bought by the quart in Margate. Their singing was loud and tuneless when it wasn’t drowned out by the rain and thunder. It had been worse when they were sober. Now and then one of them was taken with a fit of laughter that gave way to an explosion of coughing. That the man hadn’t spewed up his lungs was a miracle.

Pilot, captain, and bleeding engineer, Wise thought, commanding a crew of layabout drunks dredged out of a Billingsgate tavern by the fool of a merchant who had hired the launch. Wise was a lighterman by trade, and carried cargo upriver and down, but he had signed on for this cruise across the Channel to France because he couldn’t turn down the pay, which was five times what it should be. And it was the pay that was the two-edged sword, as the saying went – overlarge for the time spent, and that implied risk, although he was damned if he knew what sort.

The boy fed coal to the boiler with a big scoop, doing his duty, hunkering down in the falling rain and no doubt wishing he were lying abed wherever he called home. He had been sick on the Channel crossing, his first time at sea, he had told Wise. And the last, no doubt. He wasn’t made for it. The boy set the scoop down, sheltering his face with his hand, and with the other he picked up a heavy iron poker and stirred the coals, which glowed orange, throwing out a welcome heat. He had done his work steadily enough, despite the rain and in between puking over the side.

The launch had come around through the Dover Strait from a no-name, ramshackle dock on a deserted stretch of shore below Calais, where they had loaded a round dozen of beef kegs in the dead of night. If the kegs actually contained beef, Wise thought, he would eat his hat. Contraband was more like it, although the kegs were too light for brandy. But it was none of his business – his commission was purely temporary – and he had learned to shut off any curiosity at the tap. Curiosity was a beehive of trouble. And he wasn’t of the variety of lighterman who helped himself to cargo, either. Sooner or later that caper would spell the end of a man’s livelihood, or the gibbet, like as not. He looked back downriver toward the east, trying to hurry the dawn, but it was early yet, and the thick clouds would hide the daylight until the sun was well up.

When the rain fell off and made talking easier, Wise said, “There on the larboard side lies Egypt Bay, Billy, and with the Cliffe Marshes beyond. You can see the black shadow of the rise there along the shore. When the moon looks out you’ll make out the mouth of the bay, but on a filthy night like this it’s all one. Nought but smugglers and river pirates since the dawn of time in Egypt Bay. I’ve heard stories of the old Shade House Inn, with signal lights in the top window, and an honest man as good as dead if he came upon it on a dark night. There were tunnels away under the marsh, full of plunder brought in from distant lands. Like as not the plunder lies there today, although you’d be a fool to search for it. It’s still a den of cutthroats when the sun sets. What do you think of that, Billy?”

The boy looked out over the water, peering at the southern shore, but said nothing, although his eyes were wide and searching.

“There was a keg at the Shade House,” Wise said, looking ahead at the river, “full of rum, with a severed head aswim in it that they say was the Duke of Monmouth, preserved in spirits these many years. The rogues would drink of it and then top off the keg so that the head was always a-brewing. Many’s the time that the Duke’s head would rise up out of the keg and have his say, a-dripping rum from his mouth...”

The boy shouted a startled, “There!” just as the rain beat down again. He stood up and pointed with the iron poker. Wise looked sharply back to port, seeing with shocked surprise that a black cutter bore down on them, already close – six men on the thwarts leaning hard into muffled oars, black kerchiefs over their faces. The cutter must have rowed out of Egypt Bay, meaning to take the launch – What comes of speaking of the Devil, Wise thought.

“All hands!” he shouted, although the singing continued aft as he swung the wheel hard to port, thinking to run in toward shore – to run her aground if he had to and damn the cargo. The crew could earn their keep if they chose to stay and fight.

But it was too late. He heard the thud of a grappling hook striking home, the launch slewing sideways with the weight of the cutter, which backed water hard, coming around and slamming sideways into the launch, the pirates shipping their oars and swarming over the low gunwale.

The flap of the canvas flew back, the singing at an end, but the first man out from under the canopy was shot in the chest at close range. He reeled backward, pushing the canvas toward the stern with his head and his flung-back arms, the heavy, wet canopy encumbering the other three men, who tried to fight their way clear – sober enough now.

Wise abandoned the wheel, looking hard toward shore, still a good distance away, the launch turning in a lazy arc. Pistol shots mingled with the crack of thunder, the two running together. The river pirates were intent upon murder, and Wise wondered again what was in the kegs and how the pirates bloody well knew.

He stepped in a low crouch to the starboard railing, meaning to throw himself overside and take his chances with the river, but he saw that the boy still stood as if frozen. Wise grabbed him by the shoulder and shouted, “Can you swim, Billy?” He looked up in the same moment to see one of the pirates, a huge man, whose long black beard flowed out from beneath his kerchief, leveling a pistol at him. Without waiting for Billy’s reply, Wise picked the boy up bodily, spun around, and heaved him over the railing. The bullet punched Wise sideways, a searing pain in his left shoulder. He knew without question that the pirates would kill them all, and that he would just as surely drown in the river if he leapt in. With his good hand he snatched up the iron poker from beside the coal oven. It felt pitifully light to him now, but it was the only weapon within reach.

The big man who had shot him had turned away to club one of the crew with his pistol, the man crawling across the deck, as if he might yet slip beneath the railing and swim away. The pirate bent over the now-still form, placed the barrel against the back of the man’s head, and pulled the trigger. Wise, knowing that it was futile even as he sprang forward, hammered the bar down upon the big man’s head, heaving his full weight behind the blow, although already weakening from the bleeding wound in his shoulder, his left arm slick with blood. The bar tore itself out of Wise’s grip as he was shot in the neck by someone unseen and thrown back against the oven, the red-hot chimney searing his flesh through his clothing.

Wise reeled away. His senses were uncannily sharp in that moment; he heard the rain beating on the deck and hissing on the hot iron of the oven, and he smelled the rain and the river, and saw with particular clarity the lights winking along the far shore. He felt the railing in the small of his back, and he heard what sounded to him like the murmuring of the Thames flowing in its bed toward the sea, its waters unsettled and agitated by the incoming tide. He found himself teetering backward, his weight levering him over the railing – the brief sensation of falling and of the dark waters mercifully closing over him as he drowned in his own blood.

* * *

The pirates heaved the bodies into the river, then yanked the fallen canvas free and dumped it over the side in order to unencumber the deck. The big man, his forehead running blood from the blow that Wise had delivered, took a heavy pistol from within his coat, aimed it into the air, and fired it, the bullet blazing white as it exited the barrel, shooting up into the sky with a long, flaming tail, like a miniature comet. He put the pistol away in his coat, stepped to the wheel, and turned the launch back toward the bay, towing the cutter now.

The rest of the pirates watched sharply for the boy who had gone overside, although by now he would have been swept away with the corpses and so there was little chance of finding him. Within minutes they had run in around the spit of land that hid the bay’s northern shore, where they doused the glowing coal fire in the oven with buckets of water until the smoke ran white and then cleared away utterly. Taking to the cutter again, the rain beating down, they towed the launch toward the distant, farther shore, where there stood an acre or two of trees and dense shrubbery along both sides of a wide creek. They took the launch in under the trees and warped it in alongside a low, half-ruined dock with a boathouse built over it, a mere hovel of boards and tarred sailcloth, invisible from the bay.

A man in an Inverness cape stood on the dock, waiting for them, having seen the Fenian fire, as it was called, arc up into the sky. He was well satisfied with the behavior of the projectile, one of his more useful inventions, although he would experiment with it further in order to make very certain it wouldn’t fail him when he had real need for it. He held a lantern up in front of him now, the light shining on his pale features. There was an evident hump on his back, the cape doing little to hide it, and his face was as pale as a moth, although his hair was black. He walked along the dock to where the kegs were being lifted out of the launch and set down on their sides, two of the men rolling them along the planks toward a wagon that waited on shore, the horses huddled in the rain. The hunchbacked man said nothing, his attention concentrated on the kegs, which he counted carefully. After hanging his lantern on a rusty spike, he took up a mallet and crowbar and pried a stave out of the barrelhead of one of them. He regarded the contents of the keg for a time, peering closely at the bones and bone chips that studded the rubble of coal – one of the bones entire, almost certainly a human clavicle. He dipped his hand into the mix and then withdrew it, looking at the grit on his palm: coal dust, certainly, mixed with dry soil and miniscule bone fragments. He smelled and tasted it, and then dusted his hand on his trousers.

He had been promised a mixture of decomposing coal and fragments of Neolithic human bone, and he was well satisfied with what he found in the keg. If he had been cheated, he would have taken his pound of flesh, quite literally, from the London merchant who had arranged the sale of the contraband coal, despite the entertaining fact that he had refused to pay for the coal until it was delivered to him in London, and so he had no real need to pay for it at all, given that it would never be delivered.

ONE

INTO THE DARKNESS

The Bayswater Club, frequented by members of the Royal Society, stood on Craven Hill, with a view of Hyde Park to the south, and, through the trees, the roof of Kensington Palace. The view of the palace improved in autumn and winter when the trees weren’t so riotously green. What must have been half the population of London strolled up and down Bayswater Road and through the park today, sitting near the banks of the Serpentine, soaking up the sun’s warmth like salamanders after the rains of late spring. There had been an anarchist bomb, reportedly Fenian, set off just two days ago near Marble Arch, with two pedestrians killed – murdered was the more accurate term – but the city seemed already to have forgotten it.

Langdon St. Ives looked out through the window, half lost in thought, a glass of champagne in his hand. Nothing was more likely to give an anarchist the pip, it seemed to him, than public indifference, and surely there was some small justice in that, although justice was in uncommonly short supply lately. It had been a perilous two weeks, during which St. Ives had foolishly attempted to recover three notebooks of botanical illustrations drawn by Sir Joseph Banks as a boy, which had been turned over to Secretary Parsons of the Royal Society for authentication. The man who had “found” the notebooks had offered to sell them to the Society for an astonishingly moderate sum. No fewer than four experts had signed affidavits authenticating the drawings. But then, as if a magician had waved a wand over them, the original notebooks were spirited away, replaced by forgeries, and the owner of the notebooks demanded recompense.

In the interests of the Royal Society, St. Ives had played the part of a devious and interested collector to flush the thief out by offering to buy the purloined sketches. The result of the ruse had been the violent death of the thief, who, by the wildest happenstance, had apparently recognized St. Ives, knew at once that he had been practiced upon, and had fled pell-mell into the street, running with a heavy limp and carrying the three authenticated notebooks, which, along with the thief, had been trodden under the wheels of an omnibus. The man was dead where he lay, his widow and two children were left to beg in the streets, several score of early drawings by Sir Joseph Banks were ruined for good and all, and the Royal Society owed the moderate sum – no longer quite so moderate, given that it had bought them nothing – to the owner of the notebooks. It was a mess in so many ways that St. Ives scarcely knew where to begin when he attempted to itemize his regret.

The worst of it was that in a fit of remorse St. Ives had given money to the unfortunate thief’s widow when her husband lay dead in the street. The woman had unfortunately been hiding nearby with her children, she being almost certainly an accomplice as well as a witness. The money seemed to baffle her until she understood what it was for, which is to say, a guilt payment. She had loved her husband, just as St. Ives loved Alice, his own wife, and in the widow’s eyes there was no price that could be put on her husband’s bloody death. She had kept the money, however, clutching the five crowns in her hand, and had said to St. Ives, “There will be a time to judge every deed,” in a scarcely audible voice.

“I pray it won’t be soon,” he had replied, and had turned away, feeling shabbier than he remembered having felt in his life up until that time. After a period of reflection, however, it seemed to him that he might have played the fool in the matter – not his favorite instrument. The complications of the whole thing were rather too complicated to seem quite right to him now, and it had the earmarks of a plot, although the nature of the plot was beyond his grasp. He caught sight of his image in the window glass now, and saw that he looked even more craggy than usual, his long face careworn and drawn. He sat up, taking his long legs from the ottoman, suddenly restless.

He heartily wished that he were at home in Aylesford, with Alice and the children. Soon he would be, he told himself, and he looked at his pocket watch for the third time in the last half hour. The next train on the Medway Valley Line of the South Eastern Railway left Tooley Street Station in two hours, and he meant to be on it. He wouldn’t be home by suppertime, perhaps, but something very near.

He realized that his friend Tubby Frobisher was engaged in an argument with Secretary Parsons, heated on Parsons’s side – Parsons being disagreeable by nature – and ironic on Tubby’s, whose single-minded goal was to irritate Parsons. Parsons was an old man, humorless, stooped, and narrow-shouldered. His eyebrows were heavy and wild, which gave his face a fierce appearance. There was nothing at all fierce about Tubby, whose name was perfectly appropriate, although his enormous girth and cheerful demeanor sometimes mislead his enemies into thinking that he wasn’t both quick and ready to act.

“I tell you that Quittichunk’s Tablets have no virtue at all,” Parsons said, his face flushed and his beard quivering with passion. “Complete fraud. Medicinally inert if not poisonous.” He set his empty glass down and signaled for another bottle.

“Nonsense,” said Tubby. “My Uncle Gilbert swears by them. He’s an amateur sailor, you know. Docks his steam yacht in Eastbourne Harbour. He used to feed the tablets to me as a boy, before he’d allow me to go punting on the lake. I never suffered from a moment’s scurvy. You can have my affidavit on it.”

“On the bleeding lake?” Parsons sputtered. “The man was raving.”

“Never,” Tubby said. “Quittichunk’s Tablets were efficacious there, too, you know – in the case of lunacy, that is to say. Uncle Gilbert ground them with a pestle and consumed the powder with a measured dose of whisky when he was tempted to run mad.”

Parsons blinked, speechless, his heavy features frozen into a rictus of bewildered loathing. The waiter brought the fresh bottle, which was beaded with moisture and apparently steaming cold. He poured it into Parsons’s glass, and the rush of ascending bubbles seemed to restore the man to partial equanimity.

“You remember Uncle Gilbert, Langdon?” Tubby said. “You can vouch for his sanity?”

“Indeed I can,” St. Ives replied. “As sane as you or I and with a measure left over.”

“I have no argument with that,” Parsons muttered.

St. Ives, in fact, would not swear an oath on the matter of Uncle Gilbert’s sanity, if it came down to it, although it was true that sanity was a difficult thing to define.

“Do you know that he’s come up from Dicker on a birding expedition in the Cliffe Marshes?” Tubby asked. “He’s keen on finding the great bustard, which have largely been shot out of existence.”

“He intends to bag the rest of them?” Parsons asked.

“Not Uncle Gilbert. He intends to count them. Goes off hunting with his binocle and a notebook. The bird was allegedly seen in the brushlands in the marshes by an amateur birder, although it might easily have been an enormous pheasant. Uncle Gilbert means to sort the bustard out. He’s setting up a bivouac above the bay. Another glass of this capital champagne?” Tubby asked St. Ives.

“No,” St. Ives said. “It’s wasted on me.”

“You were off your feed at lunch, I noticed. Pining for home and hearth again?”

St. Ives nodded, started to reply, but was abruptly distracted when it came into his mind that he had been promised begonia cuttings, and that he might have time to fetch them before leaving for the station. The thought perked him up considerably. Something good might come of this damnable two-weeks-long detour after all. Alice was a slave to begonias – one of her chief hobbyhorses. She could plant a fragment of a leaf in a pot of sand, and it would put down roots and produce fresh leaves in a fortnight. She would be doubly happy to see him if he arrived with cuttings, and, it seemed to him at that moment, her happiness was his own.

He bent forward and looked back out of the window, where he could see the glass roof of the conservatory, a small palm house kept by an ancient gardener named Jensen Shorter, recently the secretary of the Royal Horticultural Society. Shorter had seemed to decline in stature over the long years and was now as old as Moses and as tall as Commodore Nutt. The interior of the glass building appeared to St. Ives to be inordinately dark, given the bright afternoon, as if the coal oil heater were smoking, although why the heater would be on in midsummer was a poser. Shorter was a begonia fancier of the first water: rhizomatous exclusively, no gaudy tuberous show-offs. He had been given two-dozen new species from Brazil a year ago, but he wouldn’t hear of parting with any of the plants until his cuttings had flourished. Given that he hadn’t taken the lot of them out to the gardens at Chiswick, it wouldn’t take ten minutes for Shorter to snip off a few pieces of rhizome, which would ride home snugly in various coat pockets.

St. Ives stood up decidedly. “Good day to you both,” he said. “I’ve got to see Shorter about begonia cuttings before I set out for Tooley Street.”

“Begonias,” said Parsons dismissively, “I don’t fancy them myself. Hairy damned abominations, like something out of a nightmare.”

“I couldn’t agree more,” St. Ives said, shaking the man’s hand. “Please convey my apologies to the Society for the way this business of Banks’s notebooks fell out. I would have had it turn out in any other way than it did.”

“As would I,” Parsons said, shaking his head and scowling. “The loss in money is troubling enough, not to mention the reputation of the Society, but that’s the least of it. Forty-seven original drawings by the greatest botanist of his age reduced to muddy rubbish! Still, no one’s suggesting that you were careless in the matter. Time and chance happeneth to all of us, eh? Some of us perhaps more often than others. All the more reason to put it behind us, as they say.”

“Time and chance it will have to be,” St. Ives said, seeing that Tubby had a dangerous look about him, as if he were on the verge of committing an act of violence against Secretary Parsons. “I’ll just be off, then. Tubby, give my best to Chingford.”

“I’ll do that,” Tubby said. “I’m on my way out myself, though. I’ll see you to the street.” He drank off the rest of his champagne, nodded darkly at Parsons, and put on his hat.

They passed through the book room, which was nearly empty, although it appeared to contain a high percentage of luminaries among the several men lounging at the tables. Lord Kelvin sat alone near the window, sketching something out on a piece of foolscap. St. Ives knew two of the others by reputation, both mad doctors, who sat nattering away in Latin; one of them a wild-eyed French phrenologist and the other a crackpot criminologist from Turin University named Lombroso, whose work with imbeciles had impressed certain members of the Royal Society, especially Secretary Parsons, who was happy with the idea that the greater part of the world’s population suffered from imbecility. St. Ives was currently inclined to include himself among that number.

“There might be a bigger fool than Secretary Lambert Parsons alive in the world,” Tubby said, “but if there is, he keeps himself moderately well hidden. The man is a humorless oaf. It’s a marvel that air allows itself to enter his lungs.”

They walked down into the entry hall, where Lawrence, the doorman, was propped against the wall just inside the open door, taking advantage of a warm ray of sunlight, his eyes closed.

“Do you have a coin for Lawrence?” Tubby whispered to St. Ives. “My pockets are empty.”

St. Ives reached into his pocket, and in that instant there sounded a shattering explosion and he was thrown bodily to the floor, Tubby landing on top of him like two-hundredweight of sand. St. Ives was deafened by the blast, and he found himself looking up at the chandelier swaying dangerously overhead, plaster raining down.

“Move!” he shouted at Tubby, his voice sounding small and distant, but his friend was already pushing himself to his feet, and the two of them staggered at a run through the door, the chandelier crashing to the tiles behind them, glass crystals pelting them on the back of the legs.

Lawrence crouched on the footpath now, holding his palm over a bloody gash on the side of his head. There was the sound of screams, people shouting and running. The ground was littered with broken glass and wood, fragments of stone pots, and uprooted trees and shrubs.

Shorter lay folded in half, dead still, twenty feet away on the lawn, his neck and head canted back at an unnatural angle. St. Ives saw at once that the man’s arm was missing at the shoulder, torn off in the blast. He looked away, his chest tightening.

The glasshouse had blown to pieces. Where it had been there was a stone foundation and little more. Along the base of the inside wall, between what had been the glasshouse and the Bayswater Club proper, a gaping hole looked down into the Ranelagh Sewer. Sunlight shone through the hole, revealing the shimmering surface of the Westbourne River moving toward the Thames through its immense brick tunnel.

Secretary Parsons appeared, looking stunned. “Thank God the force of the blast went out through the glass,” he said. “Aside from the odd window and the chandelier in the entry, the club itself seems to be sound. Poor Shorter.” He shook his head, looking across the lawn. “He was with Wellington at Waterloo, you know. Ninety years old if he was a day. And now he’s done down by a damned anarchist in his own palm house.”

“Do we know that?” asked St. Ives.

“Take a look at the man,” Parsons said. “He’s been blown to pieces.”

“I mean do we know it was an anarchist’s device? Why would anarchists blow up a palm house?”

“Because they’re imbeciles. They exist to be imbeciles. No one but an imbecile would detonate a bomb in a hollow tree near Marble Arch, but the thing was done.”

Parsons and Tubby moved away toward where a policeman was just then laying a coat across Shorter’s body. It occurred to St. Ives that the totality of the old man’s begonias lay in fragments amidst the rubble. He would gather pieces of them up before he left, he thought, and Alice could carry on with them – something saved from this carnage. He stepped down onto the floor of the ruined glasshouse and looked around, seeing at once that there was a wash of fine black dust on the ground, despite the turbulence of the blast, which must have thrown most of it into the atmosphere. Several clay pots that had miraculously survived the blast burned with an orange flame, which was damned odd. He smelled a wisp of rising smoke. Greek fire? Sulfur, surely. He tried to recall the ingredients of the incendiary fluid – pitch? Resin? The smell of sulfur overrode the others. He recalled that the interior of the glasshouse had been uncommonly dark when he had looked out at it through the window. Coal gas was a filthy substance when it burned, but that scarcely explained things here, unless it had been leaking badly.

He stepped across and peered into the sewer, although it was too dark to see more than a few feet in either direction. The brick floor of the enormous pipe was so broad as to be nearly flat, with a depression in the floor along which the Westbourne rippled in its channel. There was a litter of wet brick lying about and more of the black dust. He crouched at the edge of the ragged hole and bent into the pipe, looking back upriver into utter darkness. A person could trudge all the way to Hampstead Heath in that direction, to where the Westbourne rose at Whitestone Ponds, but it would be a long and tiresome journey. He turned to look downriver, and immediately saw a light in the far distance: the mouth of the sewer, perhaps, where it emptied into the Thames below the Chelsea Embankment.

Abruptly the light shifted, however, then disappeared entirely, and then winked back on – not the mouth of the sewer at all, but a lantern some distance away, moving in the direction of the Thames. Perhaps a lone anarchist.

St. Ives stepped into the sewer, down the several feet to the floor, and set out into the musty air, the light through the hole in the sewer wall giving up almost immediately so that he quickly found himself in darkness. His going back after a lantern would simply waste time – no value in even thinking about it. And besides, a lantern would give him away. It was stealth he wanted. He trailed his left hand along the wall, watching the lantern light ahead, unable to gauge its distance. Thank God, he thought, that the moving water smelled as if it were more river than filth, but he was careful where he stepped – as careful as was possible in the darkness.

He hastened forward, emboldened by the comparatively smooth brick floor, but almost immediately he stumbled over an impediment and fell to his knees, scraping his palms on the bricks and letting out a muffled shout, cursing himself under his breath, and then staying very still. The lantern in the distance went on apace. He looked back, but could see nothing behind him now, the tunnel curving slightly to the west as it ran beneath Hyde Park. That he could still see the lantern meant that it was closer than he had thought; otherwise it, too, would be hidden by the swerve of the tunnel wall.

He pushed himself to his feet, flexing his bruised knees, and went quietly on, listening hard. The awful picture of Shorter lying dead on the lawn came into his mind, and abruptly he wished that he had a weapon of some sort. He thought of Tubby Frobisher, who was as fearless as a water buffalo and nearly as vast. Tubby would have come along with him in a cold moment if only St. Ives had thought to summon him before setting out. But there was nothing for it but to go on. Nothing ventured, he thought, nothing gained – aside from a knife in the ribs.

It came to him now that he could hear a squeaking and rattling, like axles turning, as if the moving lantern were fixed on a cart. Had they brought machinery with them? To what end...?

He heard a sharp, scraping sound behind him now. He turned, seeing too late a moving shadow lunging toward him, a man’s narrow face slightly pale against the darkness. St. Ives was borne over backward, the back of his head banging down onto the brick floor so that his skull rang with the force of it. Before he could come to his senses he was rolled bodily into the river, his assailant clutching him by the hair, pushing his head beneath the surface of the water.

St. Ives flailed with his hands, seeking a purchase on the brick, which scraped past beneath him as he was swept downward in the flood, pulled from the grip of the man who was endeavoring to drown him. He lurched upward, gasping in a breath of air and twisting around, getting his feet under him so that he managed to half stand up. Immediately he was struck hard on the right cheek with something heavy and flat – the blade of a shovel? – and he reeled back against the wall of the tunnel, his cheek throbbing with pain, holding out his hands to keep the blade away from his face, hoping that his assailant was equally blind and that it had been a lucky blow.

He saw that the distant lantern bobbed toward him now – almost certainly a second assailant, coming at a run to finish him off. The word “imbecile” was no doubt writ large on his own face where the shovel had struck him. Then he realized that he was looking upriver and not down – that the lantern was coming down from above – two lanterns, in fact, come to rescue him. He heard his assailant’s splashing footfalls receding down the tunnel. There was no lantern to be seen downstream at all now, no sound of turning axles, nothing but dark silence.

TWO

HOME AT LAST

“You say that you followed these men into the darkness alone, Langdon?” Alice asked.

“Not men, do you see. One man.”

“But you said that you believed one to be pushing a cart with a lantern on it while the other one lurked behind to waylay you. I count two.”

“Lurked, as you so accurately put it. I had no idea of anyone lurking, not until he sprang out at me.” St. Ives helped himself to a second slice of cold beef and kidney pie and poured more ale from the pitcher on the breadboard. Moonlight shone through the bullseye glass in the kitchen window, casting circular shadows on the wall behind him.

“Lurkers are clever that way,” she said. “They’ve been schooled in the art of lurking. That’s why one doesn’t wade into dark tunnels to seek them out. You’ve still got black grit along the edge of the wound.” She dipped a cloth in a basin of water and wiped gingerly at the dried blood.

The wind had come up outside, and the night beyond the wall was alive with moaning and creaking. It had been a hellish trip out from London – a three-hour wait outside Gravesend for repairs to be made to the tracks, and with every hour that passed St. Ives had regretted not having taken a coach. Walking would have made considerably more sense than waiting, or at least wouldn’t have been so wretchedly frustrating. Despite the noise of the wind, Alice had opened the front door the moment she heard him step up onto the veranda half an hour ago. She had been up waiting for him, perhaps watching from the bedroom window upstairs.

“You’re quite fortunate that you were turning away from him,” she said, peering closely at his face. “He might easily have disfigured you. You’ll have an untidy scar.”

Her dark hair was tousled from sleep, giving her a slightly wild air, and she wore a silk robe that made her appear... lithe, perhaps. She was tall, nearly six feet, and under certain circumstances could appear to be quite formidable – at the present moment, in fact – largely because of her eyes, which had the keenness of those of a predatory bird, and were intensely beautiful. It seemed to him now that he had been away a foolishly long time, and he wondered what she was wearing beneath the robe.

“What I feel most,” he said, shifting the subject into a safer realm, “is the death of the book thief. I didn’t want that. I’m certain that I behaved as a complete flat throughout. The escapade seems to me too contrived, elaborately choreographed up until the point of the man’s death, which was a grotesque accident.”

“But it’s done now, if I follow your story correctly.”

“Done and done, as was I – done to a turn.”

“Indeed. First by this mysterious book thief, and then by yourself, and then by a man with a coal shovel.”

“By myself, do you say?”

“You went into the tunnel out of a sense of guilt, it would seem. You had failed to solve the first crime, and in fact blamed yourself for compounding it. So you set out into the sewer to put things right as a salve to your conscience.”

He sat in silence considering this. It sounded logical enough to him, although equally unfair. Human motivation was surely more complex than this.

“At the time,” he said to her, “it seemed to me that there was a man’s murderer to catch, and it was within my power to do so.”

“Good enough. But you’re also telling me that you had Tubby Frobisher close at hand, but you failed to invite him to join you in the pursuit of this murderer, this anarchist?”

“I’m not persuaded that anarchy had anything to do with it,” he said.

“Ah, surely that makes a great difference. Were you worried that Tubby would be discommoded, then?”

“Tubby? Of course not. He would have seen it as sport. You know Tubby.”

“Indeed I do. I’m baffled that you didn’t know him a little better yourself when you decided to go sporting in the sewer alone.” She tossed the cloth onto the tabletop, stepped back, and gave him a steady look, staring not at the wound on his cheek, but into his eyes, holding his gaze. It wouldn’t do to look away, and clearly it was best not to answer. “The next time you behave like an impulsive schoolboy and witlessly put yourself in danger, you won’t have to go into a sewer in order to be beaten with a coal shovel. I can accommodate you in that regard right here at home.”

He had a difficult time swallowing his mouthful of pie, but he nodded his head with what he hoped was agreeable determination.

“There exist in London what have come to be called ‘the police,’” she continued. “You seem already to be aware of that fact. I distinctly recall your mentioning only five minutes ago that at least one of them was there on the grounds of the Club not long after the blast, before you made your foray into the tunnel. Did it occur to you that they might take some interest in the very thing that was interesting you at that moment?”

“I... It seemed to me that...”

“It seems to me that I don’t want a dead husband, Langdon, and your children don’t want a dead father. Can you grasp that? I believe that the cat has sufficient genius to catch my meaning. Easier than catching a mouse, I should think. It’s not your business to bring anarchists and book thieves to justice in any event. I honor you for your bravery and sacrifice, you know that, but... For God’s sake, Langdon!”

“Of course,” St. Ives said. “Of course. Quite right.” He reached for his glass and was sorry to find it empty. It came to him abruptly that she was more distraught than he had imagined – more distraught than angry. He wondered whether she was on the verge of tears, something that was blessedly rare, but far worse than anger when it happened. He felt hollow and wretched. She glared at him now, shaking her head as if confounded by his antics. In that moment he knew that it was as good as done. She would let him down easily after all.

Alice picked up the pitcher of ale and filled his glass. “Drink it,” she said. “You’ll sleep better. You look done up.”

“In a moment, Alice. Have a look at these.” He reached into his coat pockets and began to haul out chunks of begonia rhizome. There hadn’t been an opportunity earlier, but now that the storm had begun to clear, the promise of exotic begonias might chase it over the horizon. “I haven’t any idea what species. Shorter had a recent lot from Brazil, and this could easily be them, or pieces of them, rather.” He drew more from his trouser pockets, and then opened his portmanteau, which sat nearby on the floor, and picked several more from among his things. “They rained down over the lawn when...” Abruptly he pictured Shorter lying dead on the grass, and the enthusiasm went out of him.

“They’ll abide here quite well until tomorrow morning,” she told him, arranging them alongside the sink. “You, however, will do better in bed. I’m more than a little tired of it being empty.”

THREE

THE AYLESFORD SKULL

Dr. Narbondo watched as the woman, Mary Eastman by name, crossed the green and stepped over the stile into the Aylesford churchyard. Even in the moonlight he could see that there was an element of angry pride in her walk, nothing furtive or fearful, as if she had some hard words for him and was anxious to throw them into his face after all these years. “Careful you don’t take a fall,” he muttered, but at the same time he was aware that she still had a certain beauty, her hair still red, as he remembered it. He stepped clear of the shadow of the tomb behind him and stood at the edge of the open grave with its small headstone.

She stood staring at him, the grave standing between them now. “Of course,” she said. “I knew it would be you. I prayed that you were dead, but my prayers clearly went unanswered. I wanted to be certain.”

“Prayer is indeed uncertain, Mary. Flesh and blood are certain enough.” He affected a smile. The night was warm, the air clear and dry. In the grave lay a broken coffin and a scattering of bones, the skull conspicuously missing. A high mound of soil lay heaped at the head of the grave, burying the foot of the headstone. Hidden behind the nearby tomb lay the body of the sexton, his coat soaked in blood. He had taken Narbondo’s money happily enough, and had been richer for the space of some few seconds. Until Narbondo had made up his mind, he wouldn’t let Mary see the dead sexton or the skull that he had taken from the grave.

“The years haven’t been kind to you,” she said bitterly, choosing to look into his face rather than into the grave. “You’ve grown a hump, which is as it should be. It’s the mark of Cain, sure as I’m standing here.”

“The years are never kind,” he said. “But in any event I have no interest in kindness. As for the hump, I’m disappointed that you would cast such stones. That was never your way, Mary.”

“My way? What do you know of my ways, then or now? I deny that you know me.”

“And yet you knew that it was I when you received the note. Surely you did. Edward’s ghost is restless, but it hasn’t taken to writing missives. And yet despite your knowledge you came freely. That gives me a degree of hope.” He kept his voice tempered. There would be no hint of pleading or desire – quite the opposite. Just an even-handed statement of the facts, such as they had undeniably come to be over the long years.

Abruptly she began to weep, the moonlight shining on her face. A breeze stirred the leaves in a nearby willow. Somewhere in the village a dog barked and then fell silent, and there was the low sound of a horse’s whinny nearby and its hoof scuffing against loose stones. She looked up at the scattering of stars, as if searching for solace. He found the gesture tiresome.

“I thought that you would profit from seeing my half-brother’s condition,” he said to her, looking about to ascertain that they were indeed alone. “I won’t say ‘brother,’ for he was never more than half alive to me. The flesh is gone from the bones now, and the skull, the salient part of his skeleton, is missing, as you can see for yourself. He was half a brother and half a man – half a boy, to be more precise – and in death he remains so. Your kindness to him was laudable, no doubt, but misconceived. Sentimentality pays a very small dividend.”

She stared at him now with a loathing that was clearly written in her features. “What do you want?” she asked. “It’s late, and I’m weary of hearing your voice.”

“You ask a direct question. Excellent,” he said. “I have a simple proposition. I want your hand in marriage. You’re a spinster, with no prospects other than that doom that awaits us all, some of us sooner than others.” He gestured at the grave by way of explanation. “I can offer you wealth and freedom from want. I won’t press my affections upon you, however. In short, I desire what was rightfully mine thirty years ago when you were a girl of fifteen. Think carefully before you deny me.”

“Rightfully yours? Do you say so? You hanged your own brother from a tree branch, leering at him as he swung there choking. It’s my undying shame that I was too cowardly to come forward, although I still can, and you know that. You have no right to ask anything of anyone but forgiveness, which I can assure you you’ll never find on Earth. Even your own mother despises you. I’ve been told that you’ve changed your name. No doubt you despise yourself.”

“I have the right to do as I please, Mary, including abandoning a name that I had grown to loathe. And the truth is, as we both know, Edward would have hanged himself eventually, or some such thing, if I hadn’t done him the kindness. He was a sniveling little toad. As for your not coming forward when you might have, that was simply good sense. Surely you recall our bargain, and so you know that your silence has so far gained you thirty years of life. Now I’m offering you that same bargain again, except that the life that I would grant you is considerably more handsome than the life you enjoy. You’re a serving wench, or so I’m told, in my own mother’s employ. Or is it a mere charwoman? It amounts to charity in either event. I tell you plainly that you might have servants of your own, if that’s what you desire.”

She stared at him as if he were insane. “I’d sooner die,” she said.

He nodded, momentarily silent, and then said, “You’ve always been a woman who spoke plainly, Mary, when you chose to speak. One thing, though, before you take your leave...”

He turned and drew out his murdered brother’s skull from where it sat atop the wall of the tomb behind him, holding it out to her as if it were an offering. She stared at it in horror, recoiling from it. Unlike the dry bones in the grave, the skull had a mocking semblance of life: the hollows of the eyes were set with illuminated silver orbs, the mouth agape, the skull itself trepanned, the opening fitted with a clockwork mechanism beneath a crystal shell. It sat on a polished wooden base, like a trophy.

“Your paramour has been well-treated, as you can see,” he said. “In life he accounted for nothing, but in death, thanks to the skills of his own loathsome father, he has ascended to something very like the plain of glory.”

Narbondo’s interest was drawn to a movement beneath a heavy branch of the willow, a shifting glow like misty candlelight on the fine curtain of leaves. He peered at it, turning his head slightly to the side to see it more clearly. He returned the skull to its resting place, and then nodded for Mary’s benefit at the figure that was slowly taking shape in the light that hovered within the wavering shadows. “The ghost walks,” he whispered.

The semblance of a boy, Narbondo’s murdered brother, paced silently toward them, his hand outstretched, the animated branches of the willow visible through his transparent body. He seemed to see Mary standing before him, and she put her hand to her mouth in happy surprise. The ghost flickered in the moonlight, winking away and then reappearing beneath the branch as before, walking toward them again over the same ground, reaching out as if there were something that he wanted – to touch Mary’s hand, perhaps. Again he flickered away, and again he reappeared and set out. His mouth worked, as if he were trying to find words that had been choked out of him thirty years ago.

Mary started toward the ghost, sobbing aloud now, putting out her arms as if to embrace it. In that moment Narbondo sprang across the open grave like an ape, his black cloak flying behind him, a knife glinting in the hand that had held the skull only moments before. She heard him alight, and she spun around, looking in horror at the knife, reaching upward to stop the hand that swept toward her, but too late. The force of the blow knocked her over backward, blood spraying from her lacerated neck, welling out of her voiceless throat where she lay now on the ground beside the open grave. She tried to push herself up onto her elbows but fell back again and lay still.

Narbondo saw that there was a rose-shaped spattering of her blood on the headstone, shining crimson in the moonlight, which struck him as slightly theatrical, although entirely fitting. It would bloom there considerably longer than would a living rose, especially after the summer sun had baked it into the stone.

FOUR

THE WEIR

With two hours remaining before the tidal surge, the river below Aylesford was shallow, slow moving, and deserted. The day was warm and the breeze had dropped, so that the silent afternoon had a brooding and timeless air, the shadows deep and still along the wooded shore. Alice St. Ives, wearing men’s trousers and India rubber wading boots over her shoes, moved farther into the river, throwing her fishing line into the deep waters behind the weir, jigging it hard, feeling it jerk once and then release. Something was interested in it.

She was fishing her own lure, tied up out of peacock feathers, silver wire, and a strip of green wool with a barbless treble hook. She had lost two big pike in the last twenty minutes, although it might have been the same pike twice. Both of them had thrown the hook, which was frustrating, but she was anxious not to do any damage to the fish’s lips with a barbed hook, since her goal was taxidermy and not dinner. There was nothing wrong with pike stuffed with ground veal and tiny pearl onions out of the garden, though, and she might have Mrs. Langley roast one for the family after all if she caught nothing larger than the single fish that lay now in her creel.

She found that she was distracted by the silence, and her gaze was drawn again to the forest, her mind running on the unpleasant idea that someone was hidden among the trees, watching her. It was a foolish apprehension. She had actually seen nothing, and nothing stirred now in the dead air. The only sound was the tiny chatter made by small stones in the moving water that flowed out of the narrow passage in the weir. She looked back downriver at her creel – an oversized salmon basket, big enough to hold a pike. It was apparently still lodged securely among the stones on the river bottom.

She’d had to kill the pike when she’d caught it half an hour ago. Despite the damage from the gaff, the ten-pound fish was ferocious enough to tear the creel apart if it were given a chance. She had used a pike-gag to hold its mouth open in order to work the hook out of the tongue, but the creature had twisted in her grip, dislodged the gag, and lacerated her hand with its teeth. Now the fish rested in wet moss, which, along with the cool river water, would keep it fresh. She wanted a larger fish if she could catch one, for the sake of the head, which she intended to mount on a plaque and give to her husband. There was a particular giant living in the weir, which she’d had on her line more than once. Langdon had volunteered to persuade it to the surface with a nitroglycerin bomb, but Alice was a proponent of fairness, especially when it came to fishing.

Their friend Tubby Frobisher had brought the greenheart wood for her fishing rod back from an expedition to South America. It looked like English walnut, but was light and flexible, the ten-foot-long rod weighing only a couple of pounds despite the heavy fittings. It was too short for salmon or trout fishing, but perfect for the kind of coarse fishing that was Alice’s passion. She had caught a heavy-bodied carp with the pole in the pond on their own property – an enormous thing with scales the size of twopenny pieces, black with burnished gold slashes on the side and a golden underbelly, quite the most beautiful thing she had ever seen. Unfortunately the fixative that St. Ives had developed had failed to harden the skin, and in the end the carp was ruined, which seemed an almost criminal offense to her. She would try his newly reconstituted fixative on the pike, if she managed to land him.