6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

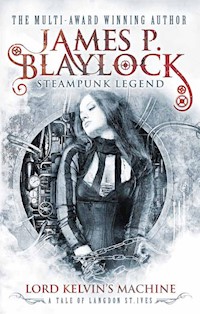

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

Within the magical gears of Lord Kelvin's incredible machine lies the secret of time. The deadly Dr. Ignacio Narbondo would murder to possess it and scientist and explorer Professor Langdon St. Ives would do anything to use it. For the doctor it means mastery of the world and for the professor it means saving his beloved wife from death. A daring race against time begins...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

ALSO BY JAMES P. BLAYLOCK

AND AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

Homunculus

The Aylesford Skull

The Aylesford Skull Limited Edition

TITAN BOOKS

Lord Kelvin’s Machine

Print edition ISBN: 9780857689849

E-book edition ISBN: 9780857689856

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: March 2013

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

James P. Blaylock asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Copyright © 1992, 2013 James P. Blaylock

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers.

Please email us at [email protected] or write to us at Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website.

WWW.TITANBOOKS.COM

This book is for Viki

And for Mark Duncan, Dennis Meyer, and Bob Martin.

The best is in the blood, there’s no coincidence about it.

Contents

Epigraph

Prologue

Part I: In the Days of the Comet

The Peruvian Andes

Dover

London and Harrogate

London and Harrogate Again

Norway

London

Part II: The Downed Ships: Jack Owlesby’s Account

The Hansom Cab Lunatic

The Practicing Detective at Sterne Rat

Aloft in a Balloon

My Adventure at the Hoisted Pint

Villainy at Midnight

Parsons Bids Us Adieu

Part III: The Time Traveler

In the North Sea

The Saving of Binger’s Dog

The Time Traveler

Limehouse

Mrs. Langley’s Advice

The Return of Dr. Narbondo

Epilogue

About the Author

...And we cannot even regard ourselves as a constant; in this flux of things, our identity itself seems in a perpetual variation; and not infrequently we find our own disguise the strangest in the masquerade.

ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON

“Crabbed Age and Youth”

PROLOGUE

MURDER IN THE SEVEN DIALS

Rain had been falling for hours, and the North Road was a muddy ribbon in the darkness. The coach slewed from side to side, bouncing and rocking, and yet Langdon St. Ives was loath to slow the pace. He held the reins tightly, looking out from under the brim of his hat, which dripped rainwater in a steady stream. They were two miles outside Crick, where they could find fresh horses—if by then it was fresh horses that they needed.

Clouds hid the moon, and the night was fearfully dark. St. Ives strained to see through the darkness, watching for a coach driving along the road ahead. There was the chance that they would overtake it before they got into Crick, and if they did, then fresh horses wouldn’t matter; a coffin for a dead man would suffice.

His mind wandered, and he knew he was tired and was fueled now by hatred and fear. He forced himself to concentrate on the road ahead. Taking both the reins in his left hand, he wiped rainwater out of his face and shook his head, trying to clear it. He was foggy, though. He felt drugged. He squeezed his eyes shut and shook his head again, nearly tumbling off the seat when a wave of dizziness hit him. What was this? Was he sick? Briefly, he considered reining up and letting Hasbro, his gentleman’s gentleman, drive the coach. Maybe he ought to give it up for the rest of the night, get inside and try to sleep.

His hands suddenly were without strength. The reins seemed to slip straight through them, tumbling down across his knees, and the horses, given their head, galloped along, jerking the coach behind them as it rocked on its springs. Something was terribly wrong with him—more than mere sickness—and he tried to shout to his friends, but as if in a dream his voice was airy and weak. He tried to pluck one of the reins up, but it was no use. He was made of rubber, of mist...

Someone—a man in a hat—loomed up ahead of the coach, running out of an open field, up the bank toward the road. The man was waving his hands, shouting something into the night. He might as well have been talking to the wind. Hazily, it occurred to St. Ives that the man might be trouble. What if this were some sort of ambush? He flopped helplessly on the seat, trying to hold on, his muscles gone to pudding. If that’s what it was, then it was too damned bad, because there was nothing on earth that St. Ives could do to save them.

The coach drove straight down at the man, who held up a scrap of paper—a note, perhaps. Rainwater whipped into St. Ives’s face as he slumped sideways, rallying his last few remnants of strength, shoving out his hand to pluck up the note. And in that moment, just before all consciousness left him, he looked straight into the stranger’s face and saw that it wasn’t a stranger at all. It was himself who stood at the roadside, clutching the note. And with the image of his own frightened face in his mind, St. Ives fell away into darkness and knew no more.

They had traveled almost sixteen miles since four that afternoon, but now it was beginning to seem that continuing would be futile. The black night was cold, and the rain still beat down, thumping onto the top of the coach and flooding the street six inches deep in a river that flowed down High Holborn into the Seven Dials. The pair of horses stood with their heads bowed, streaming rainwater and standing nearly to their fetlocks in the flood. The streets and storefronts were empty and dark, and as Langdon St. Ives let the drumming of raindrops fill his head with noise, he dreamed that he was a tiny man helplessly buried in a coal scuttle and that a fresh load of coal was tumbling pell-mell down the chute...

He jerked awake. It was two in the morning, and his clothes were muddy and cold. On his lap lay a loaded revolver, which he meant to use before the night was through. The coach overturning outside Crick had cost them precious hours. What that had meant—seeing the ghost of himself on the road—St. Ives couldn’t say. Most likely it meant that he was falling apart. Desperation took a heavy toll. He might have been sick, of course, or tired to the point of hallucination, except that the fit had come over him so quickly, and then passed away entirely, and he had awakened to find himself lying in the mud of a ditch along the roadway, wondering how on earth he had gotten here. It was curious, but even more than curious, it was unsettling.

Long hours had gone by since, and during those hours Ignacio Narbondo might easily have spirited Alice away. He might have... He stared out into the darkness, shutting the thought out of his mind. The chase had led them to the Seven Dials, and now the faithful Bill Kraken, whose arm had been broken when the carriage overturned, was searching through a lodging house. Narbondo would be there, and Alice with him. St. Ives told himself that, and heedlessly rubbed the cold metal of the pistol, his mind filled with thoughts even darker than the night outside.

Generally, he was the last man on earth to be thinking about “meting out justice,” but there in the rainy Seven Dials street he felt very much like that proverbial last man, even though Hasbro, his gentleman’s gentleman, sat opposite him on the seat, sleeping heavily, wrapped in a greatcoat and carrying a revolver of his own.

And it wasn’t so much a desire for justice that St. Ives felt; it was cold, dark murder. He hadn’t spoken in three hours. There was nothing left to say, and it was too late at night, and St. Ives was too full of his black thoughts to make conversation; he was empty by now of anything save the contradictory thoughts of murder and of Alice, and he could find words for neither of those. If only they knew for certain where she was, where he had taken her... The Seven Dials was a mystery to him, though—such a tangle of streets and alleys and cramped houses that there was no sorting it out even in daylight, let alone on a night like this. They were close to him, though. Kraken would root him out. St. Ives fancied that he could feel Narbondo’s presence in the darkness around him.

He watched the street past the wet curtain. Behind them a mist-shrouded lamp shone in a second-story window. There would be more lamps lit as the night drew on into morning, and for the first time the thought sprang into St. Ives’s head that he had no desire to see that morning. Morning was insupportable without Alice. To hell with Narbondo’s death. The gun on St. Ives’s lap was a pitiful thing. Killing Narbondo would yield the satisfaction of killing an insect—almost none at all. It was life that mattered, Alice’s life. The life of the London streets on an April morning was a phantasm. Her life alone had color and substance.

He wondered if he was bound, ultimately, for a madhouse, following in the sad footsteps of his father. Alice was his sanity. He knew that now. A year ago such a thought would have puzzled him. Life had largely been a thing of beakers and calipers and numbers. Things change, though, and one became resigned to that.

There was a whistle. St. Ives sat up, closed his fingers over the revolver handle, and listened through the rain. He shoved half out through the door, the coach rocking gently on its springs and the sodden horses shaking themselves in anticipation, as if finally they would be moving—somewhere, anywhere out of the flood. A sudden shout rang out from ahead, followed by the sound of running footsteps. Another shout, and Bill Kraken, looking nearly drowned, materialized through the curtain of water, running hard and pointing wildly back over his shoulder.

“There!” he shouted. “There! It’s him!”

St. Ives leaped into the street and slogged after Kraken, running heavily, the rain nearly blinding him.

“The coach!” Kraken yelled, out of breath. He turned abruptly and grabbed for St. Ives’s arm. There was the rattling sound of another coach in the street and the clop of horse’s hooves. Out of the darkness plunged a teetering old cabriolet drawn by its single horse, the driver exposed to the weather and the passenger half hidden by the curtain fixed across the narrow, coffin-shaped side chamber. The cab slewed around into the flood, the horse throwing streamers of water from its hooves, and the driver—Ignacio Narbondo—whipping the reins furiously, his feet jammed against the apron to keep himself from flying out.

St. Ives leaped into the street, lunging for the horse’s neck and shouting futilely into the rain. The fingers of his right hand closed over a tangle of streaming mane, and he held on as he was yanked off his feet, waving the pistol in his left hand, his heels dragging on the wet road as the horse and cab brushed past him and tore away, slamming him backward into the water. He fired the already-cocked pistol straight into the air, rolled onto his side as he cocked it again, and fired once more at the hurtling shadow of the cab.

A hand clutched his arm. “The coach!” Kraken yelled again, and St. Ives hauled himself heavily out of the water-filled gutter and lunged after him.

Hasbro tossed at the reins even as St. Ives and Kraken clambered in, and the pair of horses lurched off down the narrow street, following the diminishing cab, which swayed and pitched and flung its way toward Holborn. As soon as St. Ives was in and had caught his balance, he threw the coach door open again and leaned out, squinting through the ribbons of water that flew up from the wheels and from the horses’ hooves. The coach banged along, tossing him from side to side, and he aimed his pistol in a thousand directions, never fixing it on his target long enough for him to be able to squeeze the trigger.

They had Narbondo, though. The man was desperate. Too desperate, maybe. Their haste was forcing him into recklessness. And yet if they didn’t pursue him closely they would lose him again. An awful sense of destiny swarmed over St. Ives. He held on and gritted his teeth as the dark houses flew past. Soon, he thought. Soon it’ll be over, come what will. And no sooner had he thought this than the cabriolet, charging along a hundred yards ahead now, banged down into a water-filled hole in the street.

Its horse stumbled and fell forward, its knees buckling. The tiny cab spun like a slowly revolving top as Narbondo threw up the reins and held on to the apron, sliding half out, his legs kicking the air. The cab tore itself nearly in two, and the sodden curtain across the passenger chamber flew out as if in a heavy wind. A woman—Alice—tumbled helplessly into the street, her hands bound, and the cabriolet crashed down atop her, pinning her underneath. Narbondo was up almost at once, scrambling for a footing in the mire and staggering toward where Alice lay unmoving.

St. Ives screamed into the night, weighed down by the heavy dreamlike horror of what he saw, of Alice coming to herself, suddenly struggling, trapped beneath the overturned cabriolet. Hasbro reined in the horses, but for St. Ives, even a moment’s waiting was too much waiting, and he threw himself through the open door of the moving coach and into the road, rolling up onto his feet and pushing himself forward into the onslaught of rain. Twenty yards in front of him, Narbondo crawled across the wreckage of the cab as the fallen horse twitched in the street, trying and failing to stand up, its leg twisted back at a nearly impossible angle.

St. Ives pointed the pistol and fired at Narbondo, but the bullet flew wide, and it was the horse that whinnied and bucked. Desperately, St. Ives smeared rainwater out of his face with his coat sleeve, staggering forward, shooting wildly again when he saw suddenly that Narbondo also had a pistol in his hand and that he now crouched over the trapped woman. He supported Alice’s shoulders with his left arm, the pistol aimed at her temple.

Horrified, St. Ives fired instantly, but he heard the crack of the other man’s pistol before he was deafened by his own, and through the haze of rain he saw its awful result just as Narbondo was flung around sideways with the force of St. Ives’s bullet slamming into his shoulder. Narbondo managed to stagger to his feet, laughing a hoarse seal’s laugh, before he collapsed across the ruined cab that still trapped Alice’s body.

St. Ives dropped the pistol into the flood and fell to his knees. Finishing Narbondo meant nothing to him anymore.

PART I

IN THE DAYS OF THE COMET

THE PERUVIAN ANDES

ONE YEAR LATER

Langdon St. Ives, scientist and explorer, clutched a heavy alpaca blanket about his shoulders and stared out over countless miles of rocky plateaus and jagged volcanic peaks. The tight weave of ivory-colored wool clipped off a dry, chill wind that blew across the fifty miles of Antarctic-spawned Peruvian Current, up from the Gulf of Guayaquil and across the Pacific slope of the Peruvian Andes. A wide and sluggish river, gray-green beneath the lowering sky, crept through broad grasslands behind and below him. Moored like an alien vessel amid the bunch grasses and tola bush was a tiny dirigible, silver in the afternoon sun and flying the Union Jack from a jury-rigged mast.

At St. Ives’s feet the scree-strewn rim of a volcanic cone, Mount Cotopaxi, fell two thousand feet toward steamy open fissures, the crater glowing like the bowl of an enormous pipe. St. Ives waved ponderously to his companion Hasbro, who crouched some hundred yards down the slope on the interior of the cone, working the compression mechanism of a Rawls-Hibbing Mechanical Bladder. Coils of India-rubber hose snaked away from the pulsating device, disappearing into cracks in the igneous skin of the mountainside.

A cloud of fierce sulphur-laced steam whirled suddenly up and out of the crater in a wild sighing rush, and the red glow of the twisted fissures dwindled and winked, here and there dying away into cold and misty darkness. St. Ives nodded and consulted a pocket watch. His left shoulder, recently grazed by a bullet, throbbed tiredly. It was late afternoon. The shadows cast by distant peaks obscured the hillsides around him. On the heels of the shadows would come nightfall.

The man below ceased his furious manipulations of the contrivance and signaled to St. Ives, whereupon the scientist turned and repeated the signal—a broad windmill gesture, visible to the several thousand Indians massed on the plain below. “Sharp’s the word, Jacky,” muttered St. Ives under his breath. And straightaway, thin and sailing on the knife-edged wind, came a half-dozen faint syllables, first in English, then repeated in Quechua, then giving way to the resonant cadence of almost five thousand people marching in step. He could feel the rhythmic reverberations beneath his feet. He turned, bent over, and, mouthing a quick silent prayer, depressed the plunger of a tubular detonator.

He threw himself flat and pressed an ear to the cold ground. The rumble of marching feet rolled through the hillsides like the rushing cataract of a subterranean river. Then, abruptly, a deep and vast explosion, muffled by the crust of the earth itself, heaved at the ground in a tumultuous wave, and it appeared to St. Ives from his aerie atop the volcano as if the grassland below were a giant carpet and that the gods were shaking the dust from it. The marching horde pitched higgledy-piggledy into one another, strewn over the ground like dominoes. The stars in the eastern sky seemed to dance briefly, as if the earth had been jiggled from her course. Then, slowly, the ground ceased to shake.

St. Ives smiled for the first time in nearly a week, although it was the bitter smile of a man who had won a war, perhaps, but had lost far too many battles. It was over for the moment, though, and he could rest. He very nearly thought of Alice, who had been gone these twelve months now, but he screamed any such thoughts out of his mind before he became lost among them and couldn’t find his way back. He couldn’t let that happen to him again, ever—not if he valued his sanity.

Hasbro labored up the hillside toward him carrying the Rawls-Hibbing apparatus, and together they watched the sky deepen from blue to purple, cut by the pale radiance of the Milky Way. On the horizon glowed a misty semicircle of light, like a lantern hooded with muslin—the first faint glimmer of an ascending comet.

DOVER

LONG WEEKS EARLIER

The tumbled rocks of Castle Jetty loomed black and wet in the fog. Below, where the gray tide of the North Sea fell inch by inch away, green tufts of waterweed danced and then collapsed across barnacled stone, where brown penny-crabs scuttled through dark crevices as if their sidewise scramble would render them invisible to the men who stood above. Langdon St. Ives, wrapped in a greatcoat and shod in hip boots, cocked a spyglass to his eye and squinted north toward the Eastern Docks.

Heavy mist swirled and flew in the wind off the ocean, nearly obscuring the sea and sky like a gray muslin curtain. Just visible through the murk some hundred-fifty yards distant, the steamer H.M.S. Ramsgate heaved on the ground swell, its handful of paying passengers having hours since wended their way shoreward toward one of the inns along Castle Hill Road—all the passengers, that is, but one. St. Ives felt as if he’d stood atop the rocks for a lifetime, watching nothing at all but an empty ship.

He lowered the glass and gazed into the sea. It took an act of will to believe that beyond the Strait lay Belgium and that behind him, a bowshot distant, lay the city of Dover. He was overcome suddenly with the uncanny certainty that the jetty was moving, that he stood on the bow of a sailing vessel plying the waters of a phantom sea. The rushing tide below him bent and swirled around the edges of thrusting rocks, and for a perilous second he felt himself falling forward.

A firm hand grasped his shoulder. He caught himself, straightened, and wiped beaded moisture from his forehead with the sleeve of his coat. “Thank you.” He shook his head to clear it. “I’m tired out.”

“Certainly, sir. Steady on, sir.”

“I’ve reached the limits of my patience, Hasbro,” said St. Ives to the man beside him. “I’m convinced we’re watching an empty ship. Our man has given us the slip, and I’d sooner have a look at the inside of a glass of ale than another look at that damned steamer.”

“Patience is its own reward, sir,” replied St. Ives’s manservant.

St. Ives gave him a look. “My patience must be thinner than yours.” He pulled a pouch from the pocket of his greatcoat, extracting a bent bulldog pipe and a quantity of tobacco. “Do you suppose Kraken has given up?” He pressed curly black tobacco into the pipe bowl with his thumb and struck a match, the flame hissing and sputtering in the misty evening air.

“Not Kraken, sir, if I’m any judge. If our man went ashore along the docks, then Kraken followed him. A disguise wouldn’t answer, not with that hump. And it’s an even bet that Narbondo wouldn’t be away to London, not this late in the evening. For my money he’s in a public house and Kraken’s in the street outside. If he made away north, then Jack’s got him, and the outcome is the same. The best...”

“Hark!”

Silence fell, interrupted only by the sighing of wavelets splashing against the stones of the jetty and by the hushed clatter of distant activity along the docks. The two men stood barely breathing, smoke from St. Ives’s pipe rising invisibly into the fog. “There!” whispered St. Ives, holding up his left hand.

Softly, too rhythmically to be mistaken for the natural cadence of the ocean, came the muted dipping of oars and the creak of shafts in oarlocks. St. Ives stepped gingerly across to an adjacent rock and clambered down into a little crab-infested grotto. He could just discern, through a sort of triangular window, the thin gray line where the sky met the sea. And there, pulling into view, was a long rowboat in which sat two men, one plying the oars and the other crouched on a thwart and wrapped in a dark blanket. A frazzle of black hair drooped in moist curls around his shoulders.

“It’s him,” whispered Hasbro into St. Ives’s ear.

“That it is. And up to no good at all. He’s bound for Hargreaves’s, or I’m a fool. We were right about this one. That eruption in Narvik was no eruption at all. It was a detonation. And now the task is unspeakably complicated. I’m half inclined to let the monster have a go at it, Hasbro. I’m altogether weary of this world. Why not let him blow it to smithereens?”

St. Ives stood up tiredly, the rowboat having disappeared into the fog. He found that he was shocked by what he had said—not only because Narbondo was very nearly capable of doing just that, but also because St. Ives had meant it. He didn’t care. He put one foot in front of the other these days out of what?—duty? revenge?

“There’s the matter of the ale glass,” said Hasbro wisely, grasping St. Ives by the elbow. “That and a kidney pie, unless I’m mistaken, would answer most questions on the subject of futility. We’ll fetch in Bill Kraken and Jack on the way. We’ve time enough to stroll round to Hargreaves’s after supper.”

St. Ives squinted at Hasbro. “Of course we do,” he said. “I might send you lads out tonight alone, though. I need about ten hours’ sleep to bring me around. These damned dreams... In the morning I’ll wrestle with these demons again.”

“There’s the ticket, sir,” said the stalwart Hasbro, and through the gathering gloom the two men picked their way from rock to rock toward the warm lights of Dover.

“I can’t imagine I’ve ever been this hungry before,” said Jack Owlesby, spearing up a pair of rashers from a passing platter. His features were set in a hearty smile, as if he were making a strong effort to efface having revealed himself too thoroughly the night before. “Any more eggs?”

“Heaps,” said Bill Kraken through a mouthful of cold toast, and he reached for another platter at his elbow. “Full of the right sorts of humors, sir, is eggs. It’s the unctuous secretions of the yolk that fetches the home stake, if you follow me. Loaded up with all manners of fluids.”

Owlesby paused, a forkful of egg halfway to his mouth. He gave Kraken a look that seemed to suggest he was unhappy with talk of fluids and secretions.

“Sorry, lad. There’s no stopping me when I’m swept off by the scientific. I’ve forgot that you ain’t partial to the talk of fluids over breakfast. Not that it matters a bit about fluids or any of the rest of it, what with that comet sailing in to smash us to flinders...”

St. Ives coughed, seeming to choke, his fit drowning the last few words of Kraken’s observation. “Lower your voice, man!”

“Sorry, Professor. I don’t think sometimes. You know me. This coffee tastes like rat poison, don’t it? And not high-toned rat poison either, but something mixed up by your man with the hump.”

“I haven’t tasted it,” said St. Ives, raising his cup. He peered into the depths of the dark stuff and was reminded instantly of the murky water in the night-shrouded tide pool he’d slipped into on his way back from the tip of the jetty last night. He didn’t need to taste the coffee; the thin mineral-spirits smell of it was enough. “Any of the tablets?” he asked Hasbro.

“I brought several of each, sir. It doesn’t pay to go abroad without them. One would think that the art of brewing coffee would have traveled the few miles from the Normandy coast to the British Isles, sir, but we all know it hasn’t.” He reached into the pocket of his coat and pulled out a little vial of jellybean-like pills. “Mocha Java, sir?”

“If you would,” said St. Ives. “‘All ye men drink java,’ as the saying goes.”

Hasbro dropped one into the upheld cup, and in an instant the room was filled with the astonishing heavy aroma of real coffee, the chemical smell of the pallid facsimile in the rest of their cups retreating before it. St. Ives seemed to reel with the smell of it, as if for the moment he was revitalized.

“By God!” whispered Kraken. “What else have you got there?”

“A tolerable Wiener Melange, sir, and a Brazilian brew that I can vouch for. There’s an espresso too, but it’s untried as yet.”

“Then I’m your man to test it!” cried the enthusiastic Kraken, and he held out his hand for the little pill. “There’s money in these,” he said, plopping it into his full cup and watching the result as if mystified. “Millions of pounds.”

“Art for art’s sake,” said St. Ives, dipping the end of a white kerchief into his cup and studying the stained corner of it in the sunlight shining through the casement. He nodded, satisfied, then tasted the coffee, nodding again. Over the previous year, since the episode in the Seven Dials, he had worked on nothing but these tiny white pills, all of his scientific instincts and skills given over to the business of coffee. It was a frivolous expenditure of energy and intellect, but until last week he could see nothing in the wide world that was any more compelling.

He bent over his plate and addressed Bill Kraken, although his words, clearly, were intended for the assembled company. “We mustn’t, Bill, give in to fears about this... this... heavenly visitation, to lapse into metaphysical language. I woke up fresh this morning. A new man. And the solution, I discovered, was in front of my face. I had been given it by the very villain we pursue. Our only real enemy now is time, gentlemen, time and the excesses of our own fears.”

St. Ives paused to have another go at the coffee, then stared into his cup for a moment before resuming his speech. “The single greatest catastrophe now would be for the news to leak to the general public. The man in the street would dissolve into chaos if he knew what confronted him. He couldn’t face the idea of the earth smashed to atoms. It would be too much for him. We can’t afford to underestimate his susceptibility to panic, his capacity for running amok and tearing his hair whenever it would pay him in dividends not to.”

St. Ives stroked his chin, staring at the debris on his plate. He bent forward, and in a low voice he said, “I’m certain that science will save us this time, gentlemen, if it doesn’t kill us first. The thing will be close, though, and if the public gets wind of the threat from this comet, great damage will come of it.” He smiled into the befuddled faces of his three companions. Kraken wiped a dribble of egg from the edge of his mouth. Jack pursed his lips.

“I’ll need to know about Hargreaves,” continued St. Ives, “and you’ll want to know what I’m blathering about. But this isn’t the place. Let’s adjourn to the street, shall we?” And with that the men arose, Kraken tossing off the last of his coffee. Then, seeing that Jack was leaving half a cup, he drank Jack’s off too and mumbled something about waste and starvation as he followed the rest of them toward the hotel door.

Dr. Ignacio Narbondo grinned over his tea. He watched the back of Hargreaves’s head as it nodded above a great sheet of paper covered with lines, numbers, and notations. Why oxygen allowed itself to flow in and out of Hargreaves’s lungs Narbondo couldn’t at all say; the man seemed to be animated by a living hatred, an indiscriminate loathing for the most innocent things. He gladly built bombs for idiotic anarchist deviltry, not out of any particular regard for causes, but simply to create mayhem, to blow things to bits. If he could have built a device sufficiently large to obliterate the Dover cliffs and the sun rising beyond them, there would have been no satisfying him until it was done. He loathed tea. He loathed eggs. He loathed brandy. He loathed the daylight, and he loathed the nighttime. He loathed the very art of constructing infernal devices.

Narbondo looked round him at the barren room, the lumpy pallet on the ground where Hargreaves allowed himself a few hours’ miserable sleep, as often as not to lurch awake at night, a shriek half uttered in his throat, as if he had peered into a mirror and seen the face of a beetle staring back. Narbondo whistled merrily all of a sudden, watching Hargreaves stiffen, loathing the melody that had broken in upon the discordant mumblings of his brain.

Hargreaves turned, his bearded face set in a rictus of twisted rage, his dark eyes blank as eclipsed moons. He breathed heavily. Narbondo waited with raised eyebrows, as if surprised at the man’s reaction. “Damn a man that whistles,” said Hargreaves slowly, running the back of his hand across his mouth. He looked at his hand, expecting to find heaven knew what, and turned slowly back to his bench top. Narbondo grinned and poured himself another cup of tea. All in all it was a glorious day. Hargreaves had agreed to help him destroy the earth without so much as a second thought. He had agreed with uncharacteristic relish, as if it was the first really useful task he had undertaken in years. Why he didn’t just slit his own throat and be done with life for good and all was one of the great mysteries.

He wouldn’t have been half so agreeable if he knew that Narbondo had no intention of destroying anything, that his motivation was greed—greed and revenge. His threat to cast the earth forcibly into the path of the approaching comet wouldn’t be taken lightly. There were those in the Royal Academy who knew he could do it, who supposed, no doubt, that he might quite likely do it. They were as shortsighted as Hargreaves and every bit as useful. Narbondo had worked devilishly hard over the years at making himself feared, loathed, and, ultimately, respected.

The surprising internal eruption of Mount Hjarstaad would throw the fear into them. They’d be quaking over their breakfasts at that very moment, the lot of them wondering and gaping. Beards would be wagging. Dark suspicions would be mouthed. Where was Narbondo? Had he been seen in London? Not for months. He had threatened this very thing, hadn’t he?—an eruption above the Arctic Circle, just to demonstrate the seriousness of his intent, the degree to which he held the fate of the world in his hands.

Very soon—within days—the comet would pass close enough to the earth to provide a spectacular display for the masses— foolish creatures. The iron core of the thing might easily be pulled so solidly by the earth’s magnetic field that the comet would hurtle groundward, slamming the poor old earth into atoms and all the gaping multitudes with it. What if, Narbondo had suggested, what if a man were to give the earth a push, to propel it even closer to the approaching star and so turn a long shot into a dead cert, as a blade of the turf might put it? And with that, the art of extortion had been elevated to a new plane.

Well, Dr. Ignacio Narbondo was that man. Could he do it? Narbondo grinned. His advertisement of two weeks past had drawn a sneer from the Royal Academy, but Mount Hjarstaad would wipe the sneers from their faces. They would wax grave. Their grins would set like plaster of Paris. What had the poet said about that sort of thing? “Gravity was a mysterious carriage of the body to cover the defects of the mind.” That was it. Gravity would answer for a day or two, but when it faded into futility they would pay, and pay well. Narbondo set in to whistle again, this time out of the innocence of good cheer, but the effect on Hargreaves was so immediately consumptive and maddening that Narbondo gave it off abruptly. There was no use baiting the man into ruination before the job was done.

He thought suddenly of Langdon St. Ives. St. Ives was nearly unavoidable. For the fiftieth time Narbondo regretted killing the woman on that rainy London morning one year past. He hadn’t meant to. He had meant to bargain with her life. It was desperation had made him sloppy and wild. It seemed to him that he could count his mistakes on the fingers of one hand. When he made them, though, they weren’t subtle mistakes. The best he could hope for was that St. Ives had sensed the desperation in him, that St. Ives lived day-to-day with the knowledge that if he had only eased up, if he hadn’t pushed Narbondo so closely, hadn’t forced his hand, the woman might be alive today, and the two of them, St. Ives and her, living blissfully together, pottering in the turnip garden. Narbondo watched the back of Hargreaves’s head. If it was a just world, then St. Ives would blame himself. He was precisely the man for such a job as that—a martyr of the suffering type.

The very thought of St. Ives made him scowl, though. Narbondo had been careful, but somehow the Dover air seemed to whisper “St. Ives” to him at every turning. He pushed his suspicions out of his mind, reached for his coat, and stepped silently from the room, carrying his teacup with him. On the morning street outside he smiled grimly at the orange sun that burned through the evaporating fog, then he threw the dregs of his tea, cup and all, over a vine-draped stone wall and strode away east up Archcliffe Road, composing in his mind a letter to the Royal Academy.