Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

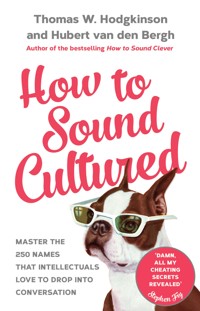

'Damn, all my cheating secrets revealed. In book form' Stephen Fry Which philosopher had the maddest hairstyle? Which novelist drank 50 cups of black coffee every day? What on earth did Simone de Beauvoir see in Jean-Paul Sartre? How to Sound Cultured offers a wry and yet profoundly useful look inside the mirrored palaces of high culture. Covering such inscrutable characters as Heidegger, Montaigne, Kahlo and Lévi-Strauss (apparently not just a designer of jeans), inscrutable polymaths Thomas W. Hodgkinson and Hubert van den Bergh – the author of the acclaimed How to Sound Clever – have done the hard work of sorting the cultural wheat from the chaff. Read this book and you'll never again mistake Rimbaud for Rambo or Georg Lukacs for George Lucas, you'll know precisely when to drop Foucault's name into a conversation and how to pronounce 'Borgesian', and you'll learn many more essential pointers for the intellectual life.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 433

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

How to Sound Cultured

How to Sound Cultured

MASTER THE 250 NAMES THAT INTELLECTUALS LOVE TO DROP INTO CONVERSATION

Thomas W. Hodgkinson and Hubert van den Bergh

Published in the UK in 2015 by Icon Books Ltd,

Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email: [email protected]

www.iconbooks.com

Sold in the UK, Europe and Asia

by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House, 74–77 Great Russell Street,

London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe and Asia

by TBS Ltd, TBS Distribution Centre, Colchester Road, Frating Green, Colchester CO7 7DW

Distributed in Australia and New Zealand by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd,

PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street,

Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in South Africa by

Jonathan Ball, Office B4, The District,

41 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock 7925

Distributed in India by Penguin Books India, 7th Floor, Infinity Tower – C, DLF Cyber City,

Gurgaon 122002, Haryana

Distributed to the trade in the USA by Publishers Group West,

1700 Fourth Street, Berkeley, CA 94710

Distributed in Canada

by Publishers Group Canada,

76 Stafford Street, Unit 300, Toronto, Ontario M6J 2S1

ISBN: 978-184831-930-1

Text copyright © 2015 Thomas W. Hodgkinson and Hubert van den Bergh

The authors have asserted their moral rights

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher

Typeset in Minion by Marie Doherty

Printed and bound in the UK by

Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

Contents

About the authors

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Party Throwers

Album Artists

Hard To Kill

Sapiosexuals

The Silver Screen

Hermits

Islanders

Sapphic Love

Self-Slaughter

Highly Sexed

Slumped Over the Soup

Creative Traumas

Who, Little Ol’ Me?

Consumed by Flames

Cunning Linguists

Synaesthesia

Rambo/Rimbaud

Champagne Socialists

Champagne Drinkers

Dipsomaniacs

Box Sets

Musicals!

F*** You

Bastards

Social Climbers

Coffee Addicts

Misshapen

Midgets

Sickly Children

Pistols at Dawn

Names that Mean Something

Actually, We’re Related

Stammerers

Adopted

Late Bloomers

Insane in the Membrane

Inspired Rock Singers

Very Late Bloomers

Just Let Me Find Out If …

Not to Be Confused With

Murderous Types

Succès de Scandale

Shaken Not Stirred

Adolf

As Blind as a Bard

Where’s Your Laundry?

Fatties

Gruesome Deaths

Stinkers

Plane Crashes

Sartorially Strange

Eureka!

The Desecrated Dead

Public Spats

Adored by Maggie

Wannabe Politicians

Fisticuffs

Militant Atheists

Loved by Woody

A Penchant for Prostitutes

Cousin Love

The Vatican Says No

Alchemists

I Can’t Take it Anymore

Coining Phrases

JFK

Car Wrecks

Athletes

Fascists

Investigated by the FBI

The Oscars

Surprise Bestsellers

The Resistance

Suitcase Mishaps

Harassed by Nazis

Four Weddings

Love Letters

Much Married

Index of main entries

About the authors

Thomas W. Hodgkinson is the author of the novel Memoirs of a Stalker (Silvertail Books, 2015). He writes regularly for The Spectator and the Daily Mail, and is a contributing editor at The Week.

Hubert van den Bergh is the author of How to Sound Clever (Bloomsbury, 2010). He has written for the Daily Telegraph and The Guardian and appeared on Vanessa Feltz’s BBC Radio 2 show.

Acknowledgements

Joint acknowledgements: Sheila Ableman; Duncan Heath; Leena Normington; Andrew Furlow; Steve White.

Thomas’s acknowledgements: Anna Yermakova; Thomas Fink; Alastair Hall; Charles Campbell; Peter Philipp Földeáky; Tom Stevens; Mia More; Ray Monk; Stephen Fry; Nick Thompson; Theo Tait; Martina Caruso; Emma Castagno; Jeremy O’Grady; Thomas Leveritt; Alexander Fiske-Harrison; Alex Preston; Russell Brand; Jocelyn Baines; Julia Hodgkinson; Dominic Hodgkinson; Nicholas Allen; Virginia Price; Philip O’Mahony; Woody Allen; James Price; Richard Curtis.

Hubert’s acknowledgements: My wife Louisa; my parents and my ten wonderful siblings and their spouses: John and Marion van den Bergh; Antonia and Olivier Hopkes; James and Louisa van den Bergh; Mary and Guy van der Westhuizen; John, George, Billy, Benedict, Caroline, Sarah Jane, and Lucy van den Bergh; James and Viviane Mayor; Claude Reed; Sue Ginsberg; Timothy Baum; Crispin Odey; Alex Buchanan; Feras Al-Chalabi; Piers Ouvaroff; Patrick Long; Dom Waugh; Louisa Elder; Michael Davies; Jasper Thornton; John Bentley; Lady Murton.

Please contact the authors with views, criticisms and all else at:

Introduction

A friend of ours was recently at a dinner party. It was given by an artist and there were intellectual types dotted around the table. After what seemed like hours of the other guests discussing intimidating figures such as Chomsky and Wittgenstein, she was relieved when the conversation turned to Rambo. Finally: a chance for her to join in. She started to talk about the gun-toting muscleman as played by Sylvester Stallone in the 1980s action movies, mentioning (a point she was particularly pleased with) that the US government at the time had taken the films seriously, viewing their popularity as an implied critique by the public of the administration’s foreign policy.

Everyone stared at her.

‘Actually,’ one messy-haired academic eventually drawled, ‘we were discussing Rimbaud, the 19th-century decadent poet.’

Yet when she told us this story, it got us thinking. Rimbaud isn’t the only one, not by a long shot. There are, for most of us, literally hundreds of cultural names we are expected to know something about, but about whom we actually don’t have much of a clue – apart from possibly recognising the name. Stefan Zweig. Bertrand Russell, Friedrich Engels. (Could you hold forth for a minute about any of these?) Then there’s Bertolt Brecht, Denis Diderot and Michel Foucault. All slippery customers. Journalists constantly cite names such as these, as proof of their cultural credentials. Intellectuals just love to drop them into conversation, like a badge of membership to some elite club, tossed onto the tabletop. We decided to listen out for these names; round them up; and then pluck out the heart of their mysteries.

We learnt a few surprising things along the way. When you look into it, it turns out these formidable individuals are usually known mainly for just one thing. For example, all you really need to know about Virginia Woolf ’s achievement as an author is that she employed a stream-of-consciousness technique. (This basically involves recording what you think, unedited. Oversharing can be the result.) That he started the anti-consumerism movement – by going and living in a forest by himself – is what Henry David Thoreau was about. And Ayn Rand devoted her life to arguing that governments had no business interfering in the lives of their citizens; they shouldn’t even ask for taxes. All intriguing concepts. And a lot less intimidating than many intellectuals would have you believe.

Another thing we learnt is that a lot of these characters knew each other, or at least crossed paths at some point. Some of them even went to bed together. Others contented themselves with a swift punch-up.

And we stumbled on a lot of surreal or surprising connections, which we’ve used to divide up our book into short chapters. Take, for example, the chapter entitled ‘Gruesome Deaths’ (page 234). This comprises three of our 250-odd cultural names, all of whom met a particularly unpleasant end: Isadora Duncan, Federico García Lorca, and Che Guevara. Apart from dying horribly, Che, when alive, smelt terrible. In fact, his hygiene was so careless his friends nicknamed him ‘The Pig’ – which is why he connects to the following chapter: ‘Stinkers’. The other ‘Stinkers’ are Mao, who died without ever having brushed his teeth, and the sweaty novelist Ernest Hemingway – who connects to the next chapter, ‘Plane Crashes’. (In fact, Ernest was unlucky enough to have experienced two such accidents, the pain of which drove him to suicide.) And so it goes on …

That’s one way of approaching How To Sound Cultured: to keep turning the pages, letting these chapter groupings and their links propel you forward. Or else you could just turn to the index, pick out a few names that have always troubled you, and take it from there. Either way, if we’ve done our job properly, you should find that this book is a quick and easy read – and that it slays a whole host of intellectual dragons, who by the time you’ve finished reading, will lie in a heap, underneath a cloud of cultural smoke.

Party Throwers

There’s a talent in recognising talent in others – and it may be that it’s for this, above all else, that the following characters will be remembered by posterity. They all threw fantastic parties, to which they invited the most gifted artists and writers of their time.

Peggy Guggenheim, art collector (1898–1979)

USAGE: In reference to any struggling artist, you might observe, ‘What he needs is a Peggy Guggenheim figure to come along.’

Peggy Guggenheim was once asked how many husbands she had had. ‘My own, or other people’s?’ she replied. Sex seems to have been a major preoccupation of the American heiress’s life, with art running it a close second. Sometimes the two coincided. She slept with the Surrealist painter Max Ernst* (who didn’t?) and even went so far as to marry him, although the union didn’t last long.

Generally, however, men didn’t treat Peggy well. Her first husband beat her and the Expressionist painter Jackson Pollock* once observed that she was so ugly, you’d first have to put a towel over her head if you wanted to make love to her. (Alas, Peggy had a bulbous nose, which she tried unsuccessfully to improve by plastic surgery.) You’d think that Pollock, who never put his theory to the test, would have been more grateful, since Guggenheim persistently invited him to the famous parties she threw, where he got to meet the great and the good of his day. Despite her huge wealth, her tightfistedness meant she famously served only dreadful scotch and ready-salted potato chips at these soirées. She did, though, became one of Pollock’s most generous patrons.

The original poor little rich girl, Guggenheim found a purpose in life when she travelled around Europe spending her dough on magnificent works of art by the geniuses of her day, including Picasso*, Kandinsky*, Klee*, Dalí, Magritte and Mondrian, to name a few. These eventually found a permanent home in a palazzo in Venice, which was renamed the Guggenheim Museum (not to be confused with the Guggenheim Museum in New York, which was created by her uncle, Solomon R. Guggenheim). There’s some debate over whether Peggy had a real eye for artistic excellence herself, or if the quality of her collection can largely be attributed to her experienced advisors.

Gertrude Stein, writer (1874–1946)

USAGE: If you’re unimpressed by someone’s garden, but don’t wish to be rude, you could quote Stein’s most famous line: ‘A rose is a rose is a rose is a rose.’

Woody Allen’s film Midnight in Paris seems to have been inspired by the thought: wouldn’t it be great to go to one of Gertrude Stein’s parties! Stein, a wealthy gay Jewish author, moved to Paris when she was 29 with her brother Leo. They soon put together such an amazing art collection, people started dropping by at all hours, just to see the pictures (and also, if they were artists, to try to sell their works). Finally the Steins decreed that they would welcome visitors only on Saturday evenings – and thus began their famous ‘salons’, which became an institution in Paris.

After falling out with her brother, Gertrude carried on the tradition with her lover, Alice B. Toklas. When guests turned up – Picasso*, Matisse, Hemingway*, Fitzgerald, and the rest – they would talk shop with Stein, while Alice entertained their wives and girlfriends in another room. For Stein was a serious author in her own right, even if her writing was almost incomprehensible. She took the idea of stream-of-consciousness to an extreme, apparently believing that, if something occurred to her, she should jot it down. She also favoured repetitions to ensure she got her message across. Her best-known line of verse was ‘A rose is a rose is a rose is a rose.’ (‘In that line,’ she later congratulated herself, ‘the rose is red for the first time in English poetry for a hundred years.’) Or here’s another sample: ‘Out of kindness comes redness and out of rudeness comes rapid same question.’ Crazy, right? But Stein failed to see that if something made no sense, it couldn’t be interesting for long.

Her biggest commercial success was the more straightforward prose work The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. With typical modernist tricksiness, it told not Alice’s life story but Gertrude’s. Stein’s legacy has been tarnished by claims she kowtowed to the Nazis during the Second World War. Even her gifts as an art collector have been called into question. One critic claimed she had a knack for ‘collecting geniuses’. But some have argued it was actually Leo who had the eye for truly talented artists, and that after the siblings parted, Gertrude’s art collection went downhill.

Stéphane Mallarmé, poet (1842–98)

USAGE: On seeing a film that’s rich in stirring imagery but isn’t quite logically coherent, you could say that it takes its place in a fine tradition that goes back to Stéphane Mallarmé.

The French littérateur Stéphane Mallarmé spent most of his life struggling to make ends meet. Yet he still managed to cobble together a few sous so he could throw a drinks party once a week at his home in the rue de Rome in Paris. The regular guests at these salons became known as the Mardistes – after the French word for Tuesday, which was when they met – and they included many of the most gifted authors of the time. W.B. Yeats, André Gide* and Paul Valéry*, to name but a few. Edgar Degas and Auguste Rodin used to shamble along too.

If you’re a poet, a good way of ensuring your legacy is to persuade a great composer to put your words to music. And that was what Mallarmé, staggeringly well connected as he was, managed to do. His poem ‘L’Après-midi d’un faune’ was set to music by Claude Debussy, and later choreographed for a notorious ballet by Vaslav Nijinsky*. Ravel and Boulez also wrote scores for poems by Mallarmé. Musicality was something he aimed for in his work. He was less interested in what words meant than in how they sounded. Indeed, he liked to introduce homophones (words that sounded exactly like other words) into his verse, so that, if it was read aloud, the listener wouldn’t be sure what was actually being said. He or she could only listen to, and enjoy, the music of the words.

Mallarmé’s emphasis on style over substance was one of his qualifications for membership of the literary movement known as Symbolism in late 19th-century France. This basically meant having interests that ran counter to those of the Realists, who wanted to depict life as accurately as possible. Mallarmé’s influence, by all accounts, was vast, and not only in literature. He inspired the Cubist and Futurist artists, and the Dadaists, and the Surrealists. More dubiously, perhaps, the British rock group Coldplay claimed to have had Mallarmé in mind when they wrote their song ‘Viva la Vida’, thereby establishing their high cultural credentials. They didn’t, however, go as far as the pop singer Lady Gaga, who for the sleeve design of one of her albums recruited the services of one of America’s best-known contemporary artists …

Footnote

* If a name has an asterisk next to it, this means it has its own entry in the book and is therefore in the index.

Album Artists

The contemporary art scene can seem a bit recherché, with few artists having much of an impact on the younger generation (or anyone else for that matter). One way to avoid this trap is to have one of your artworks used as the cover for an album by a trendy singer or rock band.

Jeff Koons, artist (b. 1955)

USAGE: A divisive figure, Koons is usually referred to in tones of contempt or adoration. Be controversial: say you think he’s ‘fine’.

In 2013, Jeff Koons designed the artwork for the album ArtPop by the pop star Lady Gaga. Some might say that ‘Gaga’ is the appropriate word here. For Koons’ artworks incorporate elements that seem designed to appeal to the pre-speech toddler: the shiny, squeaky, kitsch and cartoon. A huge balloon dog made out of chrome metal. A basketball suspended in a fish-tank of water. Sculptures of Michael Jackson and the Incredible Hulk.

A former broker, Koons has brought a Wall Street savvy to his work, turning his creative output into an industry. Some 100 assistants are employed at his factory-like studio in New York. His masterstroke has been to combine his infantile attributes with references to art’s grand tradition. As a result, serious art museums can display his works, knowing they’ll have as wide an appeal as an exhibition of erotica – which they can resemble in other respects too. His Made in Heaven series (1991) consisted of explicit photos of Koons having sex with his wife, the Hungarian porn star La Cicciolina (the word means ‘woman who appeals to fat little boys’). Obviously titillating, the arrangements were deliberately similar to those found in paintings by the 18th-century French artists Boucher and Fragonard.

The decision to feature himself in his works points to another key Koonsian feature. He is not only interested in celebrity, he’s a celebrity himself. If it’s all a confidence trick, it has been highly successful. In 2013, his Balloon Dog (Orange) became the most expensive work by a living artist ever sold at auction, after it fetched $58.4m. Whatever else one might want to say about Koons, his brazen commercialism can seem rather fun.

Gerhard Richter, artist (b. 1932)

USAGE: If someone asks you your favourite artist, you might respond, ‘I’m tempted to say Richter. But he’s worked in such a variety of styles …’

Since the death of Lucian Freud, the German artist Gerhard Richter is often said to be the world’s greatest living painter. What has he done to deserve this accolade? Crucially, he has stayed interested in using paint at a time when many regard the medium as a bit old-fashioned. An obvious example would be his Abstrakte Bilder series of the 1980s and 90s (the term just means ‘abstract pictures’). Typical examples involve a photograph printed on a large canvas, with paint thickly applied on top and then smeared with a squeegee (of the kind you might use to scrape ice from a windscreen). This simple-sounding technique often achieves the hat-trick of creating a work that is innovative, dynamic, and pleasant to look at.

As if to prove he could do it, Richter is also known for realistic paintings involving skulls and lighted candles, in the style of Georges de La Tour. For an example, see his cover design for 1988’s Daydream Nation album by the American rock band Sonic Youth. His reputation as a Picasso-like genius rests partly on the wide range of styles in which he has worked. His back catalogue also includes works inspired by the op art of the 1960s, and his beautiful stained-glass window in Cologne Cathedral, which consists of small squares, their colours chosen randomly by a computer.

Richter was born in Dresden. His father was a member of the Nazi party. His maternal aunt, a schizophrenic, was killed by the Nazis as part of their programme of euthanasia for the sick. In person, the artist combines the gravity of his traumatic background with a wry sense of humour and an air of courteous surprise, as if he’s startled to find himself still around. Painting, he says, is something to be taken seriously, a fundamental human capacity, like dancing or singing. At the same time, he dismisses the astronomical prices his works now command as ‘daft’.

Andy Warhol, artist (1928–87)

USAGE: These days Andy Warhol is most often name-checked in reference to his ‘fifteen minutes of fame’ concept.

To some, the contemporary art world seems shallow. Yes, Andy Warhol would say. Isn’t it beautiful! (Beautiful was one of his favourite words.) More interested in fame than talent, in his lurid silkscreen prints the artist chose as his subjects actors and pop stars such as Marilyn and Elvis. ‘In the future,’ Warhol memorably declared, ‘everyone will be world-famous for fifteen minutes.’ In one sense, this was wilfully controversial; in another, though, it has arguably come true. The internet now allows anyone to shout their opinions to the world. Who knows? Your Tweet may go viral.

As with many great artists, his achievement is to some extent a marketing ploy, but only to some extent. Part of the challenge is to establish new territory: for the visual artist, this means creating a kind of work that is so associated with you that ever afterwards, if anyone does anything similar, they will be said to be ripping you off. Warhol certainly achieved this with his screen prints, which fetishised the faces of the famous, along with commercial household objects such as a can of soup, say, or (as in his sleeve design for the debut album by rock band The Velvet Underground) a banana. Somewhat less impressive, perhaps, were the avant-garde films he made, with thumpingly explicit titles. Sleep (1963) consisted of footage of one of his friends sleeping. Blowjob (1964) largely focused on … well, you get the idea.

Warhol believed that if you want to be a celebrity, you need only look like one. Accordingly he wore silver wigs, which he changed regularly, so it looked as if his hair was growing. At his New York studio, The Factory, he attracted a gang of marginal characters: transvestites and drug-addled bohemians, whom he called his ‘superstars’. One hanger-on, Valerie Solanas, got fed up and shot him in 1968. Warhol, however, survived. It’s possible he felt a mere shooting was too conventional a method of assassination for an original such as himself. Not something that could be said of the bizarre way in which the Soviet Union tried to liquidate one of its greatest novelists …

Hard To Kill

Challenging the status quo will get you into hot water. The next three characters all had to remain on their guard, after narrowly escaping attempts on their lives.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, novelist (1918–2008)

USAGE: Solzhenitsyn’s name is often conjured as an example of a brave author writing about systematic state oppression while also stoically enduring it.

In 1971 the KGB tried to assassinate Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (pronounced: SOL-juh-nit-suhn) by rubbing a poisonous gel into his skin while he was buying sweets. The result was a painful rash that confined him to bed, but didn’t kill him. A few years later, the Soviet authorities had the novelist deported. He settled in the American state of Vermont, but remained on his guard against another attempt on his life. The KGB, it’s said, resorted to sending him horrific photographs (of car accidents and brain surgery, for instance) in the hope of triggering a nervous breakdown. This too proved ineffective.

Solzhenitsyn has something of the status of a literary saint, for suffering the oppression of one of the worst dictatorial regimes in history, and, with a rare obstinacy of spirit, continuing writing, and writing well, about the injustices being carried out. He knew what he was talking about. Having served with distinction in the Second World War, he was tried for subversion after he wrote a letter to a friend that hinted at criticism of Stalin. The author then served eight years in the gulags (forced labour camps), enduring horrific conditions. After Josef Stalin’s death, his successor Nikita Khrushchev permitted the publication of Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, a novel describing a day in the life of a man in a gulag. The book made Solzhenitsyn famous.

Then Khrushchev was ousted, and the author found himself back on the blacklist. Undaunted, he devoted himself to writing what some regard as his masterpiece, The Gulag Archipelago, a heavyweight tome describing the Soviet system of forced labour camps. It was this that prompted his exile – and the fact that, having won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1970, he was becoming too influential. He hated living in America, proclaiming horror at the country’s ‘TV stupor and intolerable music’. As soon as he was able, after the fall of Communism, he returned to Russia.

Baruch Spinoza, philosopher (1632–77)

USAGE: To justify paying for expensive psychoanalysis, say that you’re attempting to ‘render my emotions active, in the Spinozan sense’.

One day, on the steps of his local synagogue, the Portuguese Jewish philosopher Baruch Spinoza (pronounced: ba-ROOKH spin-O-za) was attacked by a man who thought him a heretic. Ever afterwards, he kept (and occasionally wore) the knife-slashed cloak as a reminder to himself to live more cautiously. Although Spinoza, who lived in Amsterdam, was a mild-mannered fellow, his beliefs enraged people. For he argued that the soul was not immortal, and there was no point praying to God, since He took no hand in affairs. God, Spinoza said, was essentially the sum of all the things in the universe. God was Nature.

As he explained in his masterpiece, Ethics (published posthumously), Spinoza believed there was no such thing as free will. All our actions, if we knew enough, could be predicted. The only way to have anything like free will is to have understanding, which renders our dictatorial emotions ‘active’, as he put it, instead of ‘passive’. ‘To understand,’ Spinoza declared, ‘is to be free.’

Spinoza devoted himself with astonishing purpose to these goals of freedom and understanding. He lived very frugally, ate little, abstained from sex, and often spent days on end working, without leaving the house. His only vice, it’s said, is that he sometimes enjoyed watching spiders chase flies. Academic honours were offered him and rejected. Instead, he earned a meagre income by making lenses for microscopes and telescopes. The dust from the grinding of the required powders is thought to have exacerbated the lung condition that killed him aged 44. However, Spinoza’s impact as a man of fearless rationality – one of the exemplary forefathers of the Enlightenment – is incalculable.

Leon Trotsky, revolutionary (1879–1940)

USAGE: If someone is described as a Trotskyist, or a Trotskyist Marxist, it often means they subscribe to Trotsky’s belief that the revolution has to be carried out all over the globe simultaneously: a concept sometimes expressed by the phrase ‘permanent revolution’. This is in contrast to Stalin’s belief that you should first concentrate on your own country.

Not content with banishing his former revolutionary colleague Leon Trotsky from Russia, the dictator Josef Stalin ordered his assassination. Despite the fact that Trotsky had taken refuge on the other side of the planet, in Mexico, he was tracked down. In a first attempt, killers entered his house but were fought off by bodyguards. Then, in a later incident, an assassin stole up on Trotsky while he was reading and struck him in the back of the head with an ice axe. He was clumsy and missed his mark. Trotsky spat on and wrestled with his assailant. But he died a day later from blood loss.

It goes without saying that Trotsky is in some ways a more attractive figure than Stalin. In addition to having a funky beard and moustache, he was a brilliant military leader, orchestrating the Red Army’s successful victory in the civil war that followed the 1917 revolution. But in doing so, he was clinically brutal. Consider this representative sentence from his memoirs, which is finely expressed but at the same time chilling: ‘So long as those malicious tailless apes that are so proud of their technical achievements – the animals that are called men – will build armies and wage wars, the command will always be obliged to place the soldiers between the possible death in the front and the inevitable one in the rear.’ This was Trotsky’s way of saying deserters would be shot.

He was a compelling speaker, and this, perhaps, contributed to his downfall. After the extremities of the previous years, in the 1920s many Russians longed for a return to a calmer life, and in this respect the boring-seeming Stalin seemed a safer bet. When Lenin died, Trotsky was away. Don’t hurry back, Stalin told him. Trotsky didn’t, and by the time he returned Stalin had taken control. In exile, first in Turkey and later in Mexico, he was consoled by the companionship of his wife, Natalia. But he couldn’t quite resist having an affair with a certain dashing painter …

Sapiosexuals

They say that like attracts like. So when important cultural figures sleep with important cultural figures, it’s no more surprising than when, say, Brad Pitt ends up with Angelina Jolie.

Frida Kahlo, artist (1907–54)

USAGE: Cite Kahlo as an example of an artist who was inspired by the experience of extreme physical trauma.

The art of Frida Kahlo is inextricably linked to pain. When she was just eighteen years old, she was involved in a horrific accident in Mexico City when the bus she was travelling in collided with a tram. Kahlo suffered a broken spine, collarbone, ribs, pelvis, leg and foot. An iron handrail that detached from the wreckage pierced her womb. It was while she was recuperating from these injuries, which prevented her from having children, that she resolved to be an artist, going on to create vibrant personal paintings that would ultimately make her the most successful female painter in Mexico.

During her lifetime, she was better known for being married to another Mexican artist, Diego Rivera. Their relationship was volatile, to say the least. Neither was faithful. Kahlo had affairs with women as well as men. Apparently Rivera didn’t mind about the women. Kahlo, however, drew the line when she discovered her husband had been sleeping with her younger sister, Christina. In retaliation she went to bed with the exiled Communist leader Leon Trotsky*. As responses to romantic betrayal go, that’s pretty hard to beat.

The Surrealists claimed her as their own for the naive, dreamlike quality of her art, which she filled with symbols from Mexican mythology. Kahlo has also been hailed as a feminist icon for the bold independence not only of her private life but also of her art. Its subject matter is often visceral (in one picture, she portrays herself emerging from her mother’s womb). In her many self-portraits, her gaze is direct, and she refuses to prettify herself. A handsome woman, she invariably depicts the way her eyebrows met in the middle and the downy moustache on her upper lip.

Hannah Arendt, philosopher (1906–75)

USAGE: If reading a profile of a murderer who, apart from their penchant for killing people, seems quite normal, you could exclaim: ‘Another example of Arendt’s banality of evil.’

When the German philosopher Hannah Arendt embarked on an affair with her university professor, Martin Heidegger*, it was a rather unlikely union. Arendt was a Jewish anti-fascist, while Heidegger was, at least for a time, a supporter of Nazism. (For example, it was he who instituted the Hitler salute at the university where he worked.) Much later, long after the relationship was over, Arendt defended her ex-lover against Allied charges, claiming that he had been at worst naive. Her words carried a certain weight, coming from someone who had at one point been incarcerated in a concentration camp. On top of which, she was by then a literary star, particularly renowned for her analysis of dictatorial regimes.

In her most famous work, The Origins of Totalitarianism, Arendt pointed to similarities between Stalinism and Nazism, which had in common not only their rampant anti-Semitism, but also their respective nostalgia for lost empires. Russia and Germany had both at one stage controlled colonies around the world, which they had been forced to give up.

During her research into Nazism, Arendt coined the phrase ‘the banality of evil’, to make the point that atrocious acts are often carried out by characters who are apparently not possessed by demons or just purely evil. She used it to describe Adolf Eichmann, one of the architects of the Holocaust. Arendt believed that Eichmann had been able to send countless Jews to their deaths not because he hated Jews or was a sadist, but for the tragically banal reason that he was ambitious. He knew that killing Jews would help him advance up the Nazi party ranks, and so had simply turned a blind eye to the horrors it entailed.

Martin Heidegger, philosopher (1889–1976)

USAGE: Next time you go for a walk, claim to be doing it not only for the exercise, but also in the hope of escaping from your Heideggerian ‘thrown-ness’ or Geworfenheit.

The German philosopher Martin Heidegger was once asked what people might do to lead better lives. He replied that we should all ‘spend more time in graveyards’. As advice goes, this may sound a little morbid, but Heidegger’s overarching philosophy, of which the acceptance of our mortality is an integral part, is surprisingly practical and positive.

In his work Being and Time (1927), Heidegger argued that it is only by confronting the fact we are going to die that we can start to live. Or to use his terminology, it is only by embracing Das Nichts (non-existence) that we can get to grips with Das Sein (existence). Most of us spend most of our time living ‘inauthentic’ lives: worried about the opinions of people who don’t really care for us, and who in any case cannot save us from death – so why are we striving to impress them? Secondly, he wrote that we are all ‘thrown’ into this world. By this he meant that we don’t choose to be born, or where we are born, or who our parents are, or what our education should be. As a result, our early experiences and beliefs are ‘thrown’ upon us. This ‘thrown-ness’ (Geworfenheit), like our inauthenticity, is something we must transcend. How? Heidegger recommended long walks in the countryside, pondering the miracle of existence.

If this all makes Heidegger sound relatively easy to understand, don’t be misled. One of the most important, and complicated, philosophers of the 20th century, he took his place in a tradition of German philosophical incomprehensibility, along with the likes of Immanuel Kant*. (This of course makes him a particularly impressive name to drop into conversation.) Which means that one can’t say with total certainty what he believed about anything.

Man Ray, artist and photographer (1890–1976)

USAGE: Any photograph that contains a surreal element – something absurdly out of context – may be said to owe something to the influence of Man Ray.

Like a lot of creative types, the American artist Man Ray liked to go to bed with other creative types. One example was the Belgian poet Adon Lacroix, who became his first wife in 1914. When they separated in 1919, she told him bitterly: ‘You’ll never amount to anything without me!’ His reply was understated: ‘We’ll see.’ Yet it must have seemed an increasingly crushing riposte as time went by. Soon afterwards, Ray moved to Paris and embarked on the most fertile phase of a career that would see him hailed as one of the most important artists of the 20th century.

‘There is no progress in art,’ Ray once remarked, ‘any more than there is progress in making love. There are simply different ways of doing it.’ It was a nice line, but there was definitely progress in his own artistic development. Born Emmanuel Radnitzky, the son of a tailor, he started out painting in a rather conventional style, but later, inspired by Marcel Duchamp*, he became a key member of the Surrealist movement. One of his signature works was Enigma of Isidore Ducasse: it consisted of a sewing machine (a nod to his father’s profession) draped in a piece of cloth.

Ray knew everyone who was anyone, and moved from style to style with effortless energy. He is perhaps best remembered these days for his experiments in photography. A characteristic example of his visual wit was Violon d’Ingres, a black and white photograph of his lover, the splendidly named Kiki de Montparnasse, whose naked back, seen from behind, suggests the curves of a violin. He also cannily took photographs of many of the brilliant people of his time, including James Joyce*, Gertrude Stein*, and a certain gifted and extremely beautiful protégée …

Lee Miller, photographer and muse (1907–77)

USAGE: To endear yourself to a precocious young woman, try declaring admiration for the work of Lee Miller.

It’s easy to think of men who were good-looking, lived and loved with style, and occasionally produced great art or literature, but the female examples are relatively few. One is the American photographer Lee Miller. Preternaturally beautiful, she started out as a fashion model for Vogue; then ran off to Paris to become the muse and lover of the Surrealist photographer Man Ray (among others); and later reinvented herself as a war photographer, being among the first to take pictures of the horrors of the Nazi death camps.

As a rule, her style behind the camera combined the wit of the Surrealists with the savoir faire of glossy magazines. Yet she’s more likely to be remembered for the pictures taken of her than for those she took herself (always a danger when you’re preternaturally beautiful). Perhaps the most extraordinary is an image of her, naked, in Adolf Hitler’s bathtub in Munich, taken a few days before the Führer killed himself in his Berlin bunker. In front, we can see Miller’s boots, still caked in mud from the concentration camps.

In later life, she became an alcoholic, haunted by the horrors she had seen. Some critics speak of her slightingly as a flibbertigibbet or egomaniac or both: men are always troubled by women who do as they like. After marrying the artist Roland Penrose (who was eventually knighted, meaning she became Lady Penrose), Miller settled in a farmhouse in the English countryside. She devoted herself to creating Surrealist culinary dishes such as blue spaghetti and cauliflowers made to resemble breasts, and rarely spoke of her former life – though anyone in any doubt can peruse her historic photographs, or look out for her appearance in Jean Cocteau’s* 1929 movie The Blood of a Poet. With her sleek beauty, she confirmed cinema as what a certain Canadian cultural theorist would term ‘a hot medium’. The latter would himself pop up on screen from time to time …

The Silver Screen

You know you’ve made it when you get name-checked in a movie. Better still if you actually appear on screen.

Marshall McLuhan, philosopher and media theorist (1911–80)

USAGE: A nice way to put down someone who accuses you of talking nonsense – turn to them and murmur, ‘As Marshall McLuhan used to say, “You know nothing of my work.”’

It’s such a great scene. In 1977’s Annie Hall, Woody Allen is annoyed by a self-important man in a movie queue, who keeps droning on about the theories of Marshall McLuhan. To prove him wrong, Allen produces McLuhan himself, who declares, ‘You know nothing of my work.’ Then, turning to the camera, Allen observes, ‘Boy, if only life were like this!’ In a sense, though, it was like life. ‘You know nothing of my work,’ was one of McLuhan’s favourite phrases. It was a postmodern scene (in that it drew attention to its own unreality) and McLuhan was a postmodern theorist.

‘The medium is the message’ is a key quote used to sum up his central idea. McLuhan, a Canadian academic who practically invented media studies, believed it was more interesting to consider the medium of books and films in isolation from their content. What effect does it have on us, the fact that we’re readers and film-goers? Until relatively recently, most people didn’t read. Now it looks as if few will continue to do so. Until the 1950s, most people didn’t have a TV. Now we all watch films on our laptops. According to McLuhan, these changes in the medium (regardless of whether books and films have a moral or immoral content) have a huge impact on the very structure of our thought processes, defining who we are as people. He set out his ideas in The Gutenberg Galaxy (1951) and Understanding Media (1964), which made him a huge intellectual celebrity in the 1960s. McLuhan also seems to have predicted the internet about 30 years before it was invented.

One key distinction he made was between ‘hot’ and ‘cool’ media. The way McLuhan used these terms was a bit confusing, but he would probably have regarded the modern blockbuster as hot, since it blasts out at you and you lie back and let it hit you. By contrast, a complicated book – such as one by McLuhan himself – is ‘cool’. The reader has to work hard to understand it.

Pina Bausch, choreographer (1940–2009)

USAGE: If you’re clumsy on the dance floor, suggest to your partner, ‘Let’s don blindfolds and pretend we’re taking part in a sight-impaired performance of Pina Bausch’s Café Muller.’

Pina Bausch grew up in the German town of Solingen, where her parents ran a hotel. As a girl – the name Pina is short for Philippina – she would watch couples fall in love or break up in the restaurant, and this prompted her obsession with the intricacies of human relationships. Violence and tenderness, she saw, could be two halves of the same coin. Always resistant to categories, in her work she concentrated on so-called Tanztheater, also known as dance-theatre. As the name suggests, it refers to something halfway between dance and theatre.

This blurring of boundaries characterised her career. A dancer herself, who had trained at the renowned Juilliard School in New York, in her choreography Bausch blended tradition with improvisation. She cut an androgynous figure, with sharp, strong, almost manly features; in several of her works, she would dress her male dancers in drag. Her vision could seem bleak – to some, it seemed exhaustingly so – its emphasis on strife and a search for meaning that is doomed to failure. In her most famous work, Café Muller (a direct homage to her upbringing in Solingen), many of the dancers performed with their eyes closed, knocking over chairs and tables.

Her influence, like her choreography, crossed boundaries. She has been revered and imitated by everyone from the rock star David Bowie to the film-maker Pedro Almodóvar, who incorporated her techniques into his 2001 film Talk to Her. Her ambition was never in doubt – evidenced, for instance, in her 1975 version of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, which involved a stage covered in soil, and ended with the dancers exhausted, covered in sweat and dirt.

Jean Baudrillard, philosopher (1929–2007)

USAGE: You can name-drop Baudrillard whenever you see someone purchasing a luxury item: ‘Do you really want it? Or, to paraphrase Baudrillard, do you just crave the status it denotes?’

In the sci-fi thriller The Matrix, a character is seen reading a copy of Simulacra and Simulation by the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard (pronounced: BOE-dree-ar). Fittingly so. For the film questions the nature of reality, and Baudrillard’s big idea was that images of reality have become more ‘real’ than reality. For instance, pornographic images dominate the way we think of sex more than the experience of sex itself. (To which one is tempted to say: speak for yourself, Baudrillard!) Or when we think of love, we don’t think of love as it is, but as we have seen it portrayed in movies such as Titanic or Brief Encounter, or in advertisements for after-shave or washing powder. Ditto cars, dogs, packets of biscuits – pretty much everything, in fact. To make his theory sound more impressive, the author referred to each of these received and influential images as a ‘simulacrum’ (plural: simulacra).

Taking the argument further, he pointed out that an object was never merely an object, but always came with certain ideas and values attached. For example, a BMW is not only a car but also a proof that you are well off. He got into trouble when he claimed that the Gulf War didn’t exist; it was just TV images of it that existed. Not a very tactful observation. His critics say that when you decode Baudrillard’s theories, it turns out he’s just stating the obvious. More than that, he’s overstating it. For while it might be true that we send more emails than we have conversations over the course of an average day, that doesn’t mean the internet is more real for us than the real world. It merely means we’re making use of technology.

Some have also suggested that Baudrillard may have taken himself too seriously. He was never entirely comfortable with the idea of being associated with The Matrix, and tried to distance himself from the movie, claiming that the brothers who had directed it had misunderstood his oeuvre.

F.R. Leavis, literary critic (1895–1978)

USAGE: If spotted reading a serious novel, explain that you’re trying to be more of a ‘Leavisite’ in your literary tastes.

In a scene in the 2001 romantic comedy Bridget Jones’s Diary, the heroine, who works in publishing, pretends to be on the phone to the literary critic F.R. Leavis. Her bluff is called by her boss, who points out that Leavis died in the 1970s. Why did Bridget pick Leavis? Presumably because he was the only critic she could think of. People who write about books don’t tend to become household names, but the Cambridge English literature professor was an exception.

One way he achieved his fame was by the startling severity of his literary judgements, which jolted readers into fearing that perhaps he might know something they didn’t. T.S. Eliot*, W.B. Yeats and D.H. Lawrence* were all geniuses, in Leavis’s eyes. By contrast, in The Great Tradition (1948) he pointedly ignored the works of Charles Dickens*, Thomas Hardy and Laurence Sterne*, though he later changed his mind about Dickens.

Leavis didn’t always get it right. He was a fanatical admirer of the works of one Ronald Bottrall: a judgement that has not been borne out by posterity. What he did succeed in doing was in persuading the lazy English to take the business of literature a bit more seriously. He is now generally thought to have been a sounder critic of poetry than of novels: in the case of the latter, he tended to get carried away with his insistence that a book could only be ‘good’ if it engaged with the moral complexities of the age in which it was written. Looking at the list of the authors Leavis admired, one is tempted to suggest he may have favoured ones who used double initials. His own initials, incidentally, stood for Frank Raymond.

Thomas Pynchon, novelist (b. 1937)

USAGE: Any novel that’s sprawlingly long, and mixes references to high and low culture, may be described as Pynchon-esque.

In the recent film of his novel Inherent Vice, it’s rumoured Thomas Pynchon has a cameo. Hard to be sure, since he’s such a recluse that no one knows what he looks like. If you scan images online, there are a few of a lazy-eyed, un-beautiful young man with severely protruding teeth. There’s a rumour that embarrassment about his teeth may be one reason the author shuns the limelight. He did, though, once provide the voice for a cartoon version of himself (with a paper bag on its head) in the animated TV show The Simpsons.

We know he studied at Cornell University in New York and attended lectures by Vladimir Nabokov*, despite the fact that Nabokov said he had no memory of Pynchon, and Pynchon has given out that he couldn’t understand a word Nabokov said, owing to the latter’s thick Russian accent. There are some who have found Pynchon’s books similarly incomprehensible. Hefty volumes, many of them, they are definitively postmodern, bursting with humour, digression, and a signature blend of high and low culture. One critic likened the style to a combination of Hieronymus Bosch and Walt Disney. The big one is Gravity’s Rainbow (1973), viewed by some as the greatest post-war American novel. What’s it about? As Pynchon himself might put it, it’s about 750 pages.

Other qualities of a novel that might earn the description Pynchon-esque are a mood of paranoia, and descriptions of drug use and bizarre sexual practices. The novelist Salman Rushdie is one of the few who is known to have met the author. Asked to describe him, he said he was very ‘Pynchon-esque’. The recluse tag has got people so excited, crazy theories abound as to his true identity. There’s a theory that he is really a woman named Wanda. Few have made such a virtue of shunning the limelight as Pynchon, though there are one or two who have tried. Consider the case of a certain South African novelist, who rarely even deigns to turn up in person to receive prestigious literary awards …

Hermits

You don’t have to live in a cave to write a good book, but it helps if you’re not especially sociable.

J.M. Coetzee, novelist (b. 1940)

USAGE: There doesn’t seem to be one accepted correct pronunciation of Coetzee’s name. Be confident and pronounce it as eccentrically as possible. Perhaps Cut-say-yah!

The South African novelist J.M. Coetzee is so reclusive that, on the two occasions when he won the Booker prize, he didn’t bother turning up to receive it. But when he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2003, he deigned to attend the ceremony, where he heard himself praised for novels that explore ‘the surprising involvement of the outsider’, and which display ‘well-crafted composition, pregnant dialogue and analytical brilliance’. A shy, gentle, softly spoken, lightly bearded man, Coetzee is reported to have a habit of attending dinner parties but not uttering a single word. A colleague who knew him for years claimed to have heard him laugh on only one occasion. Sadly, history doesn’t relate the nature of the joke that prompted this outburst.

Along with Nadine Gordimer, Coetzee is an example of a South African author who has dared to analyse his country’s troubled politics, and done so with such a measured intelligence that he has for the most part escaped censure. There are no quick or clumsy allocations of blame in Coetzee’s books. Disgrace – perhaps his best-known novel internationally – tells the story of a white South African literature professor who takes sexual advantage of one of his students (in a way that falls just short of rape). Sacked from his job, he moves to live with his daughter on her farm. Some black thugs break in, and rape and impregnate his daughter. Coetzee doesn’t assign a moral equivalence to the crimes. By juxtaposing them, he encourages a more thoughtful response to each.

Arthur Schopenhauer, philosopher (1788–1860)

USAGE: In a conversation about retirement plans, you might reveal your intention to ‘withdraw from society, and cultivate a Schopenhauerian detachment from the common struggle’.

One difficulty with understanding philosophers is that they’re nearly always responding to other philosophers. To understand philosopher A, you need to know something about philosopher B. So it was with Arthur Schopenhauer, whose masterwork The World As Will And Representation commented on the theories of his fellow German Immanuel Kant*.

Kant had claimed it was impossible to penetrate our veil of perception and grasp anything about the real or ‘noumenal’ world. Not so, Schopenhauer retorted. We can sense within our every mental action the workings of our will, which he termed ‘the will to live’, and conceived as a constant struggle to survive and reproduce. The original bleak existential philosopher, he was extraordinarily (one might say ‘wilfully’) pessimistic. For Schopenhauer, life was ‘a constantly prevented dying’, just as walking is ‘a constantly prevented falling’.