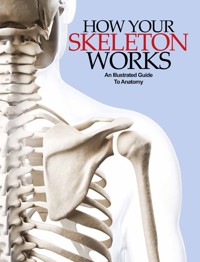

HOW YOUR SKELETON WORKS

An Illustrated Guide To Anatomy

GENERAL EDITOR: DR. PETER ABRAHAMS

This digital edition first published in 2019

Published by Amber Books Ltd United House North Road London N7 9DP United Kingdom

Website: www.amberbooks.co.uk Instagram: amberbooksltd Facebook: amberbooks Twitter: @amberbooks

Copyright © 2019 Amber Books Ltd

ISBN: 978-1-78274-452-8

All rights reserved. With the exception of quoting brief passages for the purpose of review no part of this publication may be reproduced without prior written permission from the publisher. The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. All recommendations are made without any guarantee on the part of the author or publisher, who also disclaim any liability incurred in connection with the use of this data or specific details.

www.amberbooks.co.uk

Contents

Introduction6

Head8

Neck24

Thorax30

Upper Limbs44

Pelvis62

Lower Limbs66

The Whole Body System86

Index94

Introduction

What are our bones for? To support us, to allow us to move and to protect us, you might suggest. You’d be right, but what about storing minerals, producing blood cells and hormones? Those all happen in bones, too. And clearly we can’t talk or eat without bones, but did you know that we can’t hear without them, either? Bones are for all these things. We are born with 270 of them, but, as they fuse during childhood, by the time we’re adults we have 206.

SO, TO ELABORATE on the roles they play, bones support us: the skeleton is a framework that supports the body and maintains its shape. Bones also support the eyes, the nose and the mouth. The kneecap – one of the few bones that doesn’t exist at birth – forms in early childhood to support the knee for walking and crawling. Bones provide support and flexibility at the joints and anchor the muscles that move the limbs.

Bones allow us to move: they act as attachment points for the skeletal muscles. Almost every skeletal muscle works by pulling two or more bones either closer together or further apart.

Bones protect us: the skull protects the brain, the vertebrae protect the spinal cord, and the ribcage, spine and sternum protect the heart, lungs and major blood vessels. A secondary function of the pelvis is to protect the reproductive organs.

Bones produce blood cells: red bone marrow produces red and white blood cells.

Bones store minerals: both iron and calcium are stored in bones. The yellow bone marrow inside our hollow long bones – those of our arms and legs – is used to store energy. When required, bone releases minerals into the blood, facilitating the balance of minerals in the body.

Bones produce hormones: bone cells release the hormone osteocalcin, which helps regulate blood sugar (glucose) and how fat is deposited in the body.

Bones enable us to hear: the body’s three smallest bones – the malleus, incus and stapes – help us to hear,

by transmitting and amplifying sounds from the eardrum to the inner ear. From support to movement to protection, from blood cells to hormone production, the skeleton’s functions are not just structural, but also chemical.

INSIDE A BONE

The skeleton makes up about 30-40% of an adult’s body mass, with each bone a complex living organ that consists of many cells, protein fibres and minerals, including water, collagen, calcium carbonate and calcium phosphate.

Living bone cells are found on the

edges of bones and although they make up very little of the total bone mass, they play several very important roles. They allow bones to grow and develop, to be repaired following an injury or daily wear, and to be broken down to release their stored minerals.

Arranged from head to toe, elbow to ankle, How Your Skeleton Work expertly shows you how the skeleton functions, how the different joints all work, and how you manage to sit up, move your head and turn the page to be able to read this book.

Within the middle ear are three tiny bones that carry movements of the eardrum towards the inner ear.

The knee is the most complex joint in the body, linking the thigh bone, the kneecap and the lower leg.

6

INTRODUCTION

The skeleton of an adult male. Including bones and cartilage, it accounts for one-fifth of the body’s weight. The longest bone in the body is the thigh bone (femur).

7

HEAD

The skull

The skull is the head’s natural crash helmet, protecting the brain and sense organs from damage. It is made up of 28 separate bones and is the most complex element of the human skeleton.

Frontal bone Forms forehead and roof of orbital cavity

Supra-orbital notch Hole or notch in the upper eye socket through which nerves and vessels pass

Zygomatic bone Forms the cheekbone and side wall of the eye socket

Calvaria The vault of the skull (also called cranial vault or skull-cap); the upper part of the cranium that encloses the brain

Orbit Cavity containing the eyeball and its assorted muscles, nerves and vessels; also known as the eye socket

Temporal bone One of two bones that form part of the sides and base of the skull

Glabella Joins the nasal bones and the frontal processes of the maxilla

Nasion Point of articulation between the two nasal bones and the frontal bone

Nasal bone Pair of bones forming the bridge of the nose

Inferior nasal concha (turbinate) Enlarges the surface area of the nasal cavity

Lesser wing of sphenoid bone One of two side wings extending from the body of the sphenoid bone

Infra-orbital margin The lower edge of the orbital opening

Body of mandible Horseshoe-shaped bone that forms the lower jaw

Infra-orbital foramen This is a hole through which blood vessels and a nerve pass

Maxilla One of a pair of bones that form the upper jaw

Mental foramen Hole through which nerves and vessels from the roots of the teeth pass to the lower lip and chin

Nasal septum Thin partition in the nasal cavity separating the nasal passages

The skull is the skeleton of the face and the head. The basic role of the skull is protecting the brain, the organs of special sense such as the eyes, and the cranial parts of the breathing and digestive system. It also provides attachment for

many of the muscles of the neck and head.

Although often thought of as a single bone, the skull is made up of 28 separate bones. For convenience, it is often divided into two main sections: the cranium and the mandible. The basis for

this is that, whereas most of the bones of the skull articulate by relatively fixed joints, the mandible (jawbone) is easily detached.

The cranium is then subdivided into a number of smaller regions, including:

•cranial vault (upper dome

part of the skull)

•cranial base

•facial skeleton

•upper jaw

•acoustic cavities (ears)

•cranial cavities (interior of skull housing the brain).

8

HEAD

Illuminated skull

Most of the bones of the skull are connected by sutures – immovable fibrous joints. These, and the bones inside the skull, can be seen most clearly using a brightly illuminated skull.

The areas where skull bones meet are called ‘sutures’. The coronal suture, for example, occurs between the frontal and parietal bones, and the sagittal suture connects the two parietal bones. It is important to learn the position of these joints,

because they can be confused with fractures on X-rays.

In babies, there are relatively large gaps between skull bones, allowing the head to squeeze through the birth canal without fracturing. The gaps are covered in

fibrous membranes called ‘fontanelles’. In most ‘head-first’ births, the fontanelles can be palpated (examined using the fingertips) during vaginal examinations to determine the position of the head.

Because children have only rudimentary teeth and

sinuses, their faces are smaller proportionally to adults’. (The skull of a newborn, however, is one-quarter of its body size.) As we get older, the relative size of the face diminishes as our gums shrink and we lose our teeth and the bony sockets.

Frontal sinuses Pockets of air connected to the nasal passage; not fully understood, but believed to help shape the orbitals and provide binocular vision

Greater wing of sphenoid bone One of two wings extending from the sphenoid bone

Crista galli Also known as ‘cock’s comb’ – a crest-like projection from the ethmoid bone

Ethmoidal sinus Made up of eight to ten air cells within the outer mass of the ethmoidal bone

Superior orbital fissure Space between the roof and side wall of the orbit through which vessels and nerves pass

Zygomatic arch Thin bridge of bone between the temporal and zygomatic bones

Nasal concha (turbinate) Shell-shaped bone that projects into the nasal cavity

Ramus of mandible Bone projecting upwards from the mandible behind the teeth; provides support for jaw muscles

Maxillary sinus Pyramid-shaped sinus occupying the cavity of the maxilla

9

HEAD

Side of the skull

A lateral or side view of the skull clearly reveals the complexity of the structure, with many separate bones and the joints between them.

Frontal bone Forms the forehead and upper parts of both orbits. At birth, consists of two halves which later join up

Lacrimal bone The smallest bone of the face, contributing to the orbit (eye socket)

Parietal bone One of a pair of bones forming the top and sides of the cranium

Coronal suture The joint between the frontal and parietal bones

Pterion The area where the frontal, parietal, squamous part of the temporal and greater wing of the sphenoid bones articulate

Nasal bone One of a pair of narrow, rectangular bones forming the bridge and root of nose

Zygomatic bone Forms prominent part of cheek, and some of the orbit

Lambdoid suture Occurs between the parietal and occipital bones

Occipital bone Saucer-shaped bone which forms the back and part of the base of the cranium

External acoustic meatus temporal bone The canal through to the middle and inner ears

Styloid process of temporal bone Finger-like bone to which muscles and ligaments attach

Zygomatic arch Horizontal arch formed by zygomatic and temporal bones

Maxilla Upper jaw

Sphenoid bone Forms the base of the cranium behind the eyes

Body of mandible The lower jaw

Mental foramen Opening for the passage of blood vessels and nerves

Mastoid process of temporal bone Protuberance extending behind ear; point of attachment for several neck muscles

Squamous (flat) part of temporal bone Forms part of side of cranium

Condyle of mandible Articulates with temporal bone to form temporomandibular joint

Several of the bones of the skull are paired, with one on either side of the midline of the head. The nasal, zygomatic, parietal and temporal bones all conform to this symmetry. Others, such as the ethmoid and sphenoid bones, occur

singly along the midline. Some bones develop in two separate halves and then fuse at the midline, namely the frontal bone and the mandible (lower jaw).

The bones of the skull constantly undergo a process of remodelling:

new bone develops on the outer surface of the skull, while the excess on the inside is reabsorbed into the bloodstream. This dynamic process is facilitated by the presence of numerous cells and also a good blood supply.

Occasionally, a deficiency in the cells responsible for reabsorption upsets the bone metabolism, which can result in severe thickening of the skull – osteopetrosis, or Paget’s disease – and deafness or blindness may follow.

10

HEAD

Inside the skull

The inside of the left half of the skull shows the large cranial vault (calvaria) and facial skeleton in section.

Comparing this photograph with the one of the skull’s exterior, many of the same bones can be seen, as well as additional structures. The bony part of the nasal septum (the dividing wall of the nasal cavity) consists of the vomer and the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone.

In this skull, the sphenoidal air sinuses are large. The pituitary fossa, containing the pea-sized, hormone-producing pituitary gland, projects down into the sinus. The circle marks the pterion, corresponding to the position marked on the external photograph.

The skull covers the brain, and skull fractures can lead to potentially life-threatening situations. If the side of the skull is fractured in the region of the temporal bone, the blood vessel of the middle meningeal artery may be damaged (extra dural haemorrhage). This vessel

supplies the skull bones and the meninges (outer coverings of the brain), and if ruptured, the escaping blood may cause pressure on vital centres in the brain. If not relieved, this can rapidly cause death. The artery is accessible to the surgeon if entry is made near the pterion.

Grooves for middle meningeal vessels Run upwards and backwards to the meninges, which are situated outside the brain

Coronal suture

Pituitary fossa (sella turcica) Compartment that contains the pituitary gland

Orbital part of frontal bone Forms part of eye socket

Pterion

Parietal bone

Frontal air sinus

Sphenoidal air sinus

Nasal bone

Internal acoustic meatus in petrous part of temporal bone

Perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone

Vomer

Body of mandible

Occipital bone

Lambdoid suture

Palatine maxilla

External occipital protuberance

Margin of foramen magnum

Mandibular foramen

Ramus of mandible

Angle of mandible

Pterygoid hamulus of medial pterygoid plate

11

HEAD

Top and base of the skull

The calvaria, or vault of the skull, is the upper section of the cranium, surrounding and protecting the brain.

Top of the skull exterior

Top of the skull interior

BACK

Occipital bone Just visible from above; also forms part of the back and base of skull

Coronal suture Runs between the frontal bone and the two parietal bones

Sagittal suture Joins the two parietal bones

Grooves for middle menigeal vessel Allow the passage of vessels to the meninges outside the brain

Parietal tuberosity Protruberance at the side of the skull

Vertex ‘Peak’ of the head

‘Flat’ bone of parietal Made up of three layers: inner table, diplöe and outer table

Parietal bone Paired, one on either side

Frontal bone Forms the front section of the calvaria, and the forehead

Frontal crest Projection from the frontal bone into the cranial cavity

FRONT

The four bones that make up the calvaria are the frontal bone, the two parietals and a portion of the occipital bone.

These bones are formed by a process in which the original soft connective tissue membrane ossifies (hardens) into bone

substance, without going through the intermediate cartilage stage, as happens with some other bones of the skull.

Points of interest in the calvaria include:

•The sagittal suture running longitudinally from the

lambdoid suture at the back of the head to the coronal suture.

•The vertex (highest point) of the skull; the central uppermost part, along the sagittal suture.

•The distance between the two parietal tuberosities is

the widest part of the cranium.

•The complex, interlocking nature of the sutures which enable substantial skull growth in the formative years, and provide strength and stability in the adult skull.

12

HEAD

Base of the skull

This unusual view of the skull is from below. The upper jaw and the hole through which the spinal cord goes can be seen.

Incisive fossa Depression through to the root of the canine tooth

Median palatine suture Runs between the two palatine processes of the maxillae

Palatine process of maxilla

Zygomatic bone

Sphenoid bone

Horizontal plate of palatine bone Together with palatine processes of maxillae forms the hard palate

Zygomatic arch

Vomer Forms the division between nasal cavities

Pharyngeal tubercle From which pharynx muscles hang

Foramen spinosum

Foramen ovale

Foramen lacerum

Carotid canal

Mastoid notch

Stylomastoid foramen

Jugular foramen

Mastoid process Protrusion of the temporal bone

Foramen magnum Hole through which the spinal cord joins the brain stem

External occipital crest

Mastoid foramen

External occipital protuberance

The bones found in the midline region of the base of the skull (the ethmoid, sphenoid and part of the occipital bone) develop in a different way from those of the vault of the skull. They are derived from an earlier cartilaginous structure in a process called endochondral ossification.

The maxillae are the two tooth-bearing bones of the upper jaw, one on each side. The palatine processes of the maxillae and the horizontal plates of the palatine bones form the hard palate.

PALATE DEFECTS

A cleft palate occurs when the structures of the palate

do not fuse as normal before birth, creating a gap in the roof of the mouth. This links the oral and nasal cavities. If the gap extends through to the upper jaw, a harelip will become apparent on the upper lip. However, surgery can often improve the defect.

Children with narrow

palates and crowded teeth can have an orthodontic appliance fitted which gradually increases tension across the longitudinally running midline palatine.

Over a period of months, the edges of the suture are forced apart, allowing for the growth of new bone, and extra space for the teeth.

13

HEAD

Inside the base of the skull

The floor of the skull is divided into three cranial fossae, which accommodate the brain.

Crista galli Process extending upward from the cribriform plate; the falx cerebri (sheet of meninges covering the brain) attaches here, separating the cerebral hemispheres

Foramen magnum Point of exit for the upper part of the spinal cord from the brain

Frontal sinus Air-filled space within the frontal bone, above the eyes. Connects with the nasal cavity

Cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone Fills gap (the ethmoidal notch) in the midline between the orbital parts of the frontal bone and is depressed below the level of the rest of the floor

ANTERIOR CRANIAL FOSSA

POSTERIOR CRANIAL FOSSA

MIDDLE CRANIAL FOSSA

MIDDLE CRANIAL FOSSA

KEY

Orbital plates of frontal bone

Cribriform plate of ethmoid bone

Sphenoid bone

Temporal bone

Parietal bone

Occipital bone

Internal occipital protuberance Gives attachment to the falx cerebelli, a layer of meninges passing between the two hemispheres of the cerebellum

The three fossae (cup-like depressions) have a marked step-like appearance, with the floor of the anterior cranial fossa the highest level and the floor of the posterior fossa the lowest

The nose and eyes lie under the anterior cranial fossae. The floor is formed by the frontal bone (orbital plates), the ethmoid bone

and part of the sphenoid bone. Extending upwards from the cribriform plate is a process (projection) called the crista galli.

The floor of the ‘butterfly-shaped’ middle cranial fossa is formed by the body of the sphenoid bone centrally, and the greater wings of the sphenoid and the temporal bones laterally. The

depressions in the floor contain the temporal lobes of the brain.

HOUSING THE BRAIN

The posterior fossa is the largest of the cranial fossae. It contains the cerebellum pons and medulla oblongata of the brain. The floor and posterior wall of the posterior cranial fossa are

formed mainly by the occipital bone.

The anterior wall of the posterior crania fossa leading up to the middle cranial fossa is formed by the basilar part of the occipital bone, the temporal bones (petrous and mastoid parts) and the sphenoid bone.

14

HEAD

Inside the skull in detail

There are several foramina (openings for blood vessels and nerves) within each of the three cranial fossa.

Foramen caecum Allows the passage of a vein linking the superior sagittal venous sinus (main venous drainage of the brain) to the veins in the nose

Prechiasmatic groove Contains the optic chiasma (where the two optic nerves join and redivide on their way from the optic canals)

Dorsum sellae Plate of bone forming the posterior border of the pituitary fossa

Hypoglossal canal One of a pair of channels on either side of the foramen magnum. Carries the hypoglossal nerve (the 12th cranial nerve), which supplies the muscles of the tongue

Cribriform plates Transmit olfactory nerves into the roof of the nose

Grooves from transverse sinus Provide attachment for the tentorium cerebelli (a layer of meninges that forms a ‘tent’ over the cerebellum)

Pituitary fossa (sella turcica) Contains the pituitary gland. A prominent feature of the middle fossa, lying above the sphenoidal sinuses; a sheet of meninges (diaphragma sellae) forms a roof over the fossa

Superior petrosal venous sinus Links the cavernous and the sigmoid sinuses

Clivus Sloping surface of sphenoid bone

Jugular foramen Passage for the internal jugular vein, which drains blood from the brain

There are three openings in the floor of the anterior cranial fossa: the two cribriform plates and the foramen caecum.

The anterior ethmoidal nerve (a branch of the fifth cranial nerve) enters the