6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

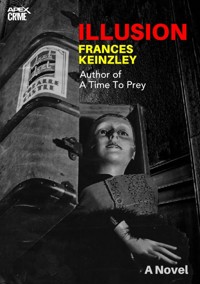

On a raw, wet, winter's day, as Eloise watches her daughter Deborah's coffin being lowered into the cold ground of the little country churchyard, her over-riding emotions are those of hatred and revenge. To Eloise, Steven appears a cold-blooded murderer, in that by forcing Deborah to agree to an abortion, he has caused her death as surely as if he had killed her with his own hands. Driven by grief and the desire for revenge, Eloise determines she will contrive somehow that Steven shall meet a murderer's rightful end at the hands of the Law.

Illusion tells the story of Eloise's ingenious scheming; of how she uses her simple- minded twin sister as, together, they leave their life of self- imposed, strangely old-fashioned seclusion, for the romantic setting of a luxury liner; and of how, on the voyage taking them halfway round the world, strange and entirely unforeseen complications arise, over which Eloise realises she has no control...

This spine-chilling mystery is one of the most exciting novels by Frances Keinzley (1922 – 2006), winner of the Literary Award in New Zealand in 1960. Keinzley is more than a talented and intelligent storyteller; she is a subtle psychologist who is able to create believable characters. Ingenious and inventive, with a surprise solution, the book is most cleverly and sensitively worked out. It is both powerful and memorable!

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

FRANCES KEINZLEY

ILLUSION

A novel

Apex-Verlag

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Das Buch

ILLUSION

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Das Buch

On a raw, wet, winter's day, as Eloise watches her daughter Deborah's coffin being lowered into the cold ground of the little country churchyard, her over-riding emotions are those of hatred and revenge. To Eloise, Steven appears a cold-blooded murderer, in that by forcing Deborah to agree to an abortion, he has caused her death as surely as if he had killed her with his own hands. Driven by grief and the desire for revenge, Eloise determines she will contrive somehow that Steven shall meet a murderer's rightful end at the hands of the Law.

Illusion tells the story of Eloise's ingenious scheming; of how she uses her simple- minded twin sister as, together, they leave their life of self- imposed, strangely old-fashioned seclusion, for the romantic setting of a luxury liner; and of how, on the voyage taking them halfway round the world, strange and entirely unforeseen complications arise, over which Eloise realises she has no control...

This spine-chilling mystery is one of the most exciting novels by Frances Keinzley (1922 – 2006), winner of the Literary Award in New Zealand in 1960. Keinzley is more than a talented and intelligent storyteller; she is a subtle psychologist who is able to create believable characters. Ingenious and inventive, with a surprise solution, the book is most cleverly and sensitively worked out. It is both powerful and memorable!

ILLUSION

To Clancy and Shannon

For their Loving Endurance

Chapter One

THE RAIN, THOUGH LIGHT, FELL WITH A CONSTANCY THAT

proved to those obliged to be out in it more drenching than the heaviest downpour. In the churchyard, it cellophaned the grey and leaning tombstones and ran down in glassy stalactites from the outspread wings of a petrified angel. Under its conforming membrane the ginger-coloured patches of newly turned earth sat like glossy hunks of amber, and against the church wall a winter tree hunched miserable as a beggar and snivelled its wet drops with maddening irregularity on to the ground below. Even the rib ends of the parson’s umbrella continued down in liquid wires so that he, in white altar plumage, stood a damp and dejected bird in his heaven-wrought cage.

Eloise Blassing stood tall and straight, her neat leathered feet not moving their disciplined position by so much as a quarter-inch throughout the long graveside service; her attentive eyes expressing neither the discomfort nor the grief that in the first instance she felt so acutely and in the second so poignantly.

She thought about the parson and his voice resounding through the rain like an organ. There was the up-pitch, the down-pitch and the drawn-out solemnity but nothing at all of its melody. Why, she wondered, did all parsons resort to the unnatural sonorous baying at funerals? Did they truly believe that it bespoke grief? Who did they hope to impress – for comfort they did not – the mourners, the Deity or their own sense of theatre?

Yes, that was it. It was theatrical, shamelessly theatrical, and the pity of it was one could not walk out on so bad a performance. A note of tasteful regret would say it all: ‘We are gathered here today to bury a young girl who, to our mortal way of thinking, was too young to die. Death at twenty-three seems to us a witless entry in the Book of Human Account, but if there is a Plan of promised hope and happiness behind the death of the very young, then let us try very hard to believe that it is kinder to be glad that Deborah has at least this promise of happiness and has escaped the certainty of Life’s misery that most surely increases with our years and our wisdom. And so, I ask Rest in Peace, not for Deborah but for you, her sorrowing kin. Go in Peace.’

It was, Eloise thought, all very depersonalizing, even without the funeral. Particularly the stone angel – certainly the last choice of memorial for Deborah’s grave. Deborah alive had not believed in angels therefore it would be unethical to mount one over her now, especially with the power of protest denied her. Also, Deborah had loved the sun, and those monstrous wings which would soon be covered with faint green slime could do nothing but throw a chillier shadow on a place already betrothed to gloom. No, it would never do.

She stopped looking at the angel and looked instead at her sister beside her, her identical twin in all except intellect. Anastasia stood with clasped hands and downcast eyes. Eloise sighed. Even in honest grief Anastasia looked as if she were pretending. Anastasia always looked as though she were pretending, as if realizing that having no positive character of her own she must borrow one from whatever the moment or the occasion offered. Eloise’s lips tightened slightly; the rejection of the angel would not be easy – Anastasia believed in them so.

The burial was almost over. A shovelful of clay had already been thrown down on the expensive coffin with its discreet polish and plain silver handles. The parson was closing his thick gold-edged book, thin red ribbons marking the more frequent services he was called upon to perform. Eloise turned away, pleased in her practical mind that all concerned would soon be out of the rain – Deborah included, who alive had so hated the damp. The parson accompanied them both to the big, black, ageing Bentley waiting at the church gates and Eloise was glad that he remained silent during the short walk and did not try to add further inanities to the countless inanities that he had already spoken. Silence was such a safe condition at any time, implying as it did an emotion or mood not necessarily felt.

Eloise had many such opinions fixed in the firmament of her intellect, and the sight of her sister’s black silk ankles beneath the hem of her long bereavement dress as she walked ahead of Eloise and the parson brought to mind the one Eloise believed in most of all; where Beauty is the tenant, the Devil is the landlord. It surprised her that Anastasia did have such beautiful ankles, the slim heel bone centring the pretty hollows either side and enhanced by the neat way Anastasia had of placing her feet. She wondered why, only now at a funeral, she should think of beauty where her unbeautiful sister was concerned and after pondering the question decided it was the legacy of the dead and that from this moment on it was going to be the most difficult thing in the world to see beauty in any measure and not think of Deborah.

At the door of the car the parson shook wet hands with Anastasia and then with Eloise, who accepted it as just one more unpleasant funeral detail before pulling her hand free and entering the big, black car. She immediately lowered the shade, not to keep private her grief but to close out the sight of the cleric’s sanctimonious face looking in.

It was only a short distance back to the house on the outskirts of the village, but the chauffeur, ever mindful of the standing instruction ‘...to drive with dignity at all times’ managed to treble the time it should have taken if driven at any speed other than that of a royal motorcade. Eloise settled back, her eyes looking straight ahead but seeing none of the stark grey countryside beyond the car windows. Her mind was travelling its own roads, and while nostalgic wanderings for most are purported to be glowing with colour and languid with scent, her roads were black and white and lonely as moon country.

She thought of Anastasia sitting so sensitively beside her, of the guilty pleasure she had seen flash in and flash out of her sister’s pale eyes at having her hand held, if only by a country parson. It had been a touch, a man’s touch, and however much Anastasia declared otherwise Eloise knew her feathery sister dreamed by day and by night of being courted and captured and of loving happily ever after. A small anger fluttered under her primly pleated bodice. She knew it was more than a personal anger against her sister or against the parson, knew it to be the age-old indignation at the vulnerability of one kind against the cunning of the other.

She herself had been vulnerable, had twenty-four years back believed in love and happy endings. The first disillusionment had been love itself; it had not been the fabled fusion of body and soul to body and soul but a furtive, clumsy collision of two bodies, one certain and knowing, her own ignorant and unrhythmic but eager to be convinced that the ugliness and deepening shame growing within her was a price worth paying. The second disillusionment had been in the discovery that there was no such thing as a happy ending, only endings like amputations, sudden and sore, and that admitting pregnancy to a lover was a slashing through of the strings holding up a marionette affair. She had wanted to die and as punishment had been made to live. Not so Deborah, Deborah had wanted to live and as punishment had been made to die.

Poor sweet Deborah. So wholly perfect in beauty with her young rounded body and long firm thrusting legs. At least Death held her suspended in mid-stride forever, had seen to it that she would never become arid and ridiculous as Anastasia and herself had become arid and ridiculous, and now that Deborah was dead they would perhaps become more arid and ridiculous without her coming every third weekend to spark them to life, those wonderful weekends when she would swoop down from her London flat to spend ‘...forty-eight tonic hours, dear aunts, among the real birds and bees and far from those other B’s in London. Dear Aunt ’Stasia! I’ll swear you’ve washed the air – I’ve never smelt it so clean. And you most darling of aunts (Eloise), you make grey seem the only colour skies should be. Why do I let myself leave you both, and Winton House?’

But she always did, each Monday morning on the 6.27. At first, she went back because she was young and London was old, and then she hurried back because Winton House was intolerable, because the whole world was intolerable wherever two people in love could not be with each other.

Only Deborah’s lover had not been a young vibrant boy as eager for her gifts as she was for his. Deborah, with an orphan’s hunger for a father image, had fallen in love with an older man whose vanity was pleased and whose lust refreshed at the chance of savouring such an offering. That their excursions in bed were, to his young mistress, an extension of the nursery warmth and intimacy she had never consciously known as a child, made his possession of her a voyage of discovery, even an addiction, and at the thought of the abstinence her pregnant body would eventually demand, it must simply have been a matter of policy to him to have her visit that back-street doctor.

Steven Maddren! Eloise rolled the name like a marble around in her mind, a mind still with the power to remain aloof from the calamities of the heart. Only once had she given all of herself to any one thing, and so well had her lesson been learned that not even grief for her dead daughter could amount to a totality within her.

She told his imagined face: I know who you are. Deborah spoke of you often, but only because she was in love with you and love cannot keep its own secret. She said such commonplace things about you, things she might have said about anyone, but it was the way she said those commonplace things that alerted me. Also, she called you Steven. Even allowing this generation’s informality you must agree that it was still a most irregular practice between a business senior and his secretary. Inconclusive? Yes, it is. But this isn’t. The night she died she tried for many hours to call your London number from Winton House. She must have considered it desperately urgent because, ill though she was, she refused to leave the telephone table until she collapsed over it and my sister and I carried her from it.

She died during the night from an induced abortion and the next morning when I sat down to telephone I found I had a lot of reading to do – all the scribbling she had done on the message pad the night before: dear Steven ... kind and dearest Steven ... please be in ... tomorrow might be too late ... I’m frightened, Steven ... frightened ... frightened ... there’s a bear inside me ... it thinks I’m a tree ... it’s clawing at my stomach ... ripping it ... tearing it ... stop him, Steven, stop him ... please be in this time ... please, please, please – and then came your telephone number, kind and dearest Steven, in English numerals, Roman numerals, in dots, in a circle, in a straight line, a vertical line, indeed there was no way that she hadn’t written it.

I suppose I, too, would have doodled at the telephone had there been a number for me to ring when it happened to me, but, in strict accordance with my father’s ethics, I was cut off from post or pigeon and bundled off to Ireland until it was over and my little bundle of shame given to an impoverished relative until it could be returned to us... an orphaned kin. Ireland in the war years was a benign place; I see now that it was a perfect place to heal in but subconsciously, I suppose, I didn’t want to heal – the death wish, perhaps? I have never been able to say with certainty that it was or was not – all I know is that my motivation for living, even for hitting back, had left me. Anastasia’s optimism was no match for my pessimism, my lethargy smothered her as well and she was the only one I would allow to share the dim little world I moved in. And that was the beginning of our withdrawal from life – so natural at any time in Ireland, itself so remote in time and disposition: nothing stirred around me to challenge me to stir within myself. I was in the world but not of it. My father’s death, followed by the ramifications of his will, required our return to England shortly after Peace was declared – the contrast between the quiet shy land we had left and the war-convulsed England we arrived in was more than I could take. I had no interest in catching up with the world and fitting in. Indeed, the very thought of it was unmitigated horror. I couldn’t get to Winton House quick enough to slam its door between ourselves and the world.

Had I seen my child from the beginning things might have been different, had she been given to me to care for and keep from infancy, she, you, and I, Mr. Maddren, might still be as separate as star is from star, but I neither saw her nor knew her until she was twelve years old, and when we did first meet I could acknowledge only that we had shared a body; I refused to accept that we shared a heart. What had a strange gawky twelve-year-old to do with me? Either emotionally or intimately? It was preposterous! She meant nothing to me – nothing at all. Such a nondescript child favouring neither me nor her over-the- hill father; she could have been Cook’s child for all the pull or evocation that failed to make itself felt. I kept strictly out of her way because she bored me – as children usually do to adults who have forgotten what it is like to be children. And she angered me, because every glimpse of her hurt and puzzled eyes made me remember only too vividly my own hurt and puzzlement.

She was a strange, strange child. The more I shunned her the more she sought me. The more I ignored her the more she made me aware of her. The more I displayed my irritation the longer and sweeter was her smile for me. I did not want to love her but she made me love her by electing to love me. My discouragement should have been too much even for the most determined adult, it wasn’t anywhere near enough for my child. Deciding to love me was for her the all of it and the end of it. It became the all of it and the end of it for me. The moment came – as it had to – when I loved her as a mother was born to love a child, irrevocably and unconditionally – and I was too ashamed to declare myself. The thought of falling from the pedestal she had put me on was intolerable.

I know now that admitting I was her mother would have assured me my place on that pedestal for all time, because more than all else Deborah was compassionate – the first attribute to divinity in love, if philosophers are to be believed. But I wasn’t compassionate, therefore I had no way of knowing that love loves to forgive or that love qualifies as a perfect love only by the imperfections it chooses to accept. Also, she was a child loving a mother, surely the most reliable and faithful love of all, and I failed to claim that love – worse, I failed to claim her. She died without knowing that I was her mother.

In time, her love might have generated that honesty in me. I feel sure it would have, only now I’ll never know – because of you, I’ll never know. So, you see, Mr. Maddren, for that alone I’m obliged to hate you. And I do. Not passionately, nor ardently nor furiously; you are not worthy of any woman’s emotional landslide, least of all mine, no, I hate you as a doctor hates a killer virus. I hate you as the fox hates the hound. I hate you as a priest hates sin. Hate that is action. Action that demands destruction. Destruction that is justified by result. It is as simple as that.

I cannot hold you entirely guilty of your violation of her; for any young girl, this is a natural hazard, any young girl, that is, who goes out into the world too soon. My daughter was too young for the world; she would always have been too young for the world even had she been ten years older. You see, she was afflicted. The affliction? That vulnerable innocence that comes with altruism or stupidity. In Deborah’s case, it was not stupidity.

While she was away at school it was easy – she was always at a given place at a given time. Her term holidays were spent with us and that was easy too. When she was at school no longer, my uncertain monarchy of her came to an end.

She insisted on being her own compass. I knew how dangerous that could be. I also recognized in her my own young fallible self. I offered her the world: she preferred to discover her own. I bribed her with my wealth: she said that to enjoy it she would have to stop living. She said she wanted to work and wish and to grow wise. To wish for things she couldn’t have because there was a happiness in wishing. To be a little bit mad and buy something she couldn’t really afford and go ‘broke’ doing so. That to feel extravagant just now and again would be like pulling the sky down around one; that extravagance was an intoxication that only the non-rich (I would have used the word poor) could know; that the poor rich couldn’t ever know it. The awful innocence of it all, and yet there were some things she knew too soon. She already knew things that the old have taken a lifetime to learn.

So far, I had simply requested her not to work. Now I wanted to forbid it and knew I couldn’t. She was eighteen with no more than a hundred or so pounds in her over-fingered bankbook. The law would agree that she was right to work rather than grow destitute. Nor was there any statute in the land that said: rich living must be accepted and enjoyed when offered.

I was her legal guardian but legal guardians can only wave a limp stick when the plans of a young woman are not counter to law and order. Nor could I exercise a mother’s prerogative and embezzle her love and sympathy. She saw me only as an indulgent aunt with too many foolish fears. I had to let her go if I was to keep her.

So, you see, Mr. Maddren, my daughter’s innocence was her violation, not you, but I do charge you with having killed her. Oh yes, you killed her as surely as if you had strangled the breath out of her and that of course makes you a murderer. I have had more than enough time to think about this and often during these past weeks I have come very close to taking a train to London and killing you, only killing you in hate would not satisfy me – I am my banker-father’s daughter and every debt must carry a little interest – it would also be morally wrong. You broke the law therefore the law must attend to you. And how will I convince the world that you have committed a crime? My dear Mr. Maddren, it is not my intention to convince the world, the less the world knows of it the better, sufficient that I know. I have judged you and found you guilty, nothing remains but to bring you to justice.

The motor-car turned in through carved gates and drew to a dignified stop in front of a large country house. From behind the wheel of the outdated limousine the chauffeur emerged with two black umbrellas and handed them to the two sisters, who, holding them high above their heads, ascended the stone steps to the doors swung wide for them by a maid wearing a long-starched apron over her sombre dress, and a serving cap with streamers.

Once in the hall, the umbrellas taken from their neatly gloved hands, Anastasia was held back by Eloise’s light touch on her arm, and for the first time since leaving the house that morning Anastasia raised her weepy red eyes to her sister. ‘Yes, Eloise?’

‘Your ankles, Anastasia.’

Anastasia succeeded in looking guilty. The least word from Eloise could always make her feel this way. ‘Yes, I know, sister, it is the rain, it has shrunk the hem, I’ll change immediately.’

Eloise nodded. ‘Please do. Black silk stockings are an indecency at any time – at a time of mourning they are a profanity.’

‘Yes Eloise.’ Fresh tears welled up in Anastasia’s eyes and slid sedately down her cheek, tears for the lovely black silken things that had given such a dancing look to her legs before she had pulled her petticoat down over them. They had been one of the secret gay and forbidden gifts from Deborah: ‘Dear Aunt ’Stasia, Nice Aunt 'Stasia, I’ve brought you some more contraband. What an awfully naughty girl you would be if you could!’

Eloise interpreted the tears as funeral tears and was moved to a rare indulgence of her silly sister. Unbuttoning her long cape and dropping it into the maid’s waiting hands, she called to Anastasia scurrying up the stairs. ‘When you come down you shall have a glass of sherry. So, dry up your tears and be quick.’

Anastasia’s face lighted up. ‘Oh, thank you, sister, thank you, that will be very nice.’ She continued up the stairs quickly, her sadness forgotten.

Chapter Two

THE MEDICAL TERM FOR IDENTICAL TWINS IS UNIOVULAR.

The explanation for them is a single seed split. It has been said that identical twins are not two beings but a double focus of one being like two sides of a door hinged by a single destiny. Nor could this notion be successfully argued considering that there is not a single variance to be found in the true uniovular twins, not even in that most exclusive of personal uniquities, the fingerprint. If one has a stunted toe, the other has a stunted toe; if one has a birth mole one millionth of an inch thick, the other has a birth mole one millionth of an inch thick; if one has fifty-three hairs to the eyelash and the forty-ninth is a shorter one, so too has the other. Also, their mental potentiality is equal at birth and only life and its experiences, or lack of them, can unequalize the balance; but this is an exterior result and not an inherent conclusion.

The theory that uniovular twins are one being is not borne out by the evidence of parents who make the rational point that from birth onwards two cradles are required, two sets of nursery garments and two feeding bottles. In later life, it is noticed that uniovular twins have between them four feet instead of the singular set of two, and that they have to be shod, and that in the matter of sustenance one portion on one plate does not come off with the same brilliance of result as did the loaves and fishes.

From the moment of their birth Lord Blassing, bank director and monopoly shareholder in shipping, steel and hotel interests, was in no doubt that when his wife was delivered of twins he was the father of two children – as his holdings implied he was an unusually astute man – nor was it any secret to his wife or to his world that he would greatly have preferred one son to two daughters though two daughters to no issue at all.

Eloise, the first to exit into a life of indolent richness, had her little clenched fist forcibly opened to take the gold pocket watch beautifully inscribed ‘To My First Son’ from her disappointed father. When Anastasia arrived twenty-two minutes later Lord Blassing retrieved the watch from the crib and dumped it in a drawer. Not until he had later swallowed three cognacs at his club did he begin to get over his disappointment and start to feel the importance of twice being a father at once, and for the first time, at the age of fifty-eight.

To act without thinking was to Lord Blassing the mark of a frightened animal, a state of mind that did not at any time qualify as valid in the rule book of human behaviour, and because he himself was not a capricious man he dedicated himself to seeing that there was nothing capricious about the daughters to whom his vast and vested interests must soon pass. He succeeded with Eloise and failed with Anastasia, who under the clandestine and counter guidance of her sister became a parasitic personality asking only to obey whenever her sister saw fit to command, which was more often than seldom. If nothing else it made the twinship a bearable relationship though not always a comfortable one.

Up until the age of eighteen Eloise was as vulnerable as a girl of eighteen can be and equally as frivolous in matters of fashion and the pursuits of fun; nor was she above enjoying the thrill of simple flirtations with the well-referenced males met in the ornate ballrooms and sumptuous country houses of her world. Only after the heartbreak of taking one too seriously who had taken her not seriously enough did Eloise discard with absolute thoroughness the remnants of girlhood, draw down the blinds on living and retreat, taking Anastasia with her; and although the many clocks in the great house ticked on with unfailing accuracy, time itself for the two sisters came to a complete standstill. They were recluses, first by choice and as the years passed irrevocably, by nature.

Visitors were neither invited nor received, and apart from a rare call from their doctor, no hand beat the massive gargoylian door knocker. They ate frugally and wore dresses of dark cloth with neither brooch nor lace fichu for relief and finishing five inches above their grey woollen ankles. Their figures remained slender and good but intentionally shapeless beneath their dirgeful dresses, and their delicate feet were solemnly shod in black leather shoes with a single bar and button across their insteps; their pale and composed hands seemed to be an impious flash of light against the thunder of their garb, and whatever positivity their faces had once had was now lost in the nonentity of pale complexions, pale grey eyes palely lashed, pale pink lips, pale brown hair pulled severely back from pale brows and twisted into a prim knot at the back of their elegant heads.

It was a manner of dress and mode of life intended not to disguise but to repel and protect – like the prickles of a porcupine and the stench of a skunk – and more Anastasia than her sister. Eloise, having been the loser once, knew that she never could again. She also knew that Anastasia in her unworldliness would gladly be attracted to all males, and that, accepting this as a factor that neither advice nor warning would change, she must see to it that no man would be attracted to her. At forty-two years of age, through their primness and outdated clothes, the sisters had managed to add almost a decade to their appearance.

Their servants were few and of long service; a gatekeeper, a gardener, a chauffeur, a cook and three maids who remained as obscure as their duties would permit and who ate better than the sisters but not so well as staff might have expected in so securely financed an establishment. But Eloise had an opinion on this too: anything more than enough was too much, and although she conscientiously saw to it that they were well fed she was equally as conscientious in seeing that they did not feast. They were good servants, untalkative and loyal to the eccentric sisters, who had been visionary enough to have the solicitor inform them that each one of them would be comfortably recompensed for life at the end of a given span of service; an announcement that did much to placate the frequent irritations of their posts and induce them to drone more zealously for the Queen Bee and her obedient court of one. Like her dear dead father, Eloise was unusually astute.

It was Eloise’s nature to speak only when it was necessary to do so, and then to say only that which needed to be said in her communications with her sister and servants, and so well was the household attuned to her ways that one of her looks was often more eloquent than ten of her utterances. After the funeral, she appeared to have even less to say and unprecedently left the lesser delegations of responsibility to Anastasia, who delighted in the importance of being able to give instructions or opinion without first having to search Eloise’s eyes for approval. The servants also welcomed the change. No matter how impressively Anastasia acted towards them she succeeded only in amusing them rather than cowing them, but being good servants and understanding the relationship between the sisters, and the lesser sister’s need for power, however brief or comic, they complied as submissively to Anastasia’s directives as they had to Eloise’s. Anastasia had not known that power could taste so sweet, nor was she ever to forget it.

That Eloise was preoccupied to the exclusion of almost all else in her well-ordered life was apparent most at table where Anastasia was able to serve her plate generously without being reminded of the perilously short distance separating greed from gluttony. It was clear that her sister no longer noticed such transgressions and, if noticing, no longer cared.

Eloise spent the finer mornings in the high-walled gardens of Winton House, sometimes sitting for long stretches of time in quiet and patient repose on one or another garden seat, other times walking the red-gravelled paths and green swards, hands tucked in her sleeves, eyes downcast on the emergence of one black shoe following the other like little black rabbits from under the hem of her gown. The dreary mornings she spent in her own secluded parlour deep within the house where she would sit, like a reproduction of ‘Whistler’s Mother’, on a ladder-back chair, neat feet at rest on the shining fender, and stare for hours on end into the contorting flames of the fire as if mesmerized.

But Eloise Blassing was far from mesmerized; never before had she brought all her marvellous mental powers together at once and for so long as she was bringing to the thought of how to bring Steven Maddren to justice and to death. That it could be done she did not doubt, a certainty endorsed by the cross-stitch sampler of her childhood, framed in speckled bamboo and hanging beside an eighteenth-century sideboard flanking the French window: ‘Through Me All Things are Possible’, Saith the Lord; that it must be done was as urgent a drive within her as life itself, so that by night and day, eating or sleeping, awake or dreaming, the problem was never away from her mind but stayed with her as firmly lodged as a neurosis.

On her instruction, a box of books was sent down from London, gilded, portentous tomes on The Law of Tort; Popular Misconceptions of Law; The Layman’s Book of Law; The Law of Equity; Common Law and Case Law. She searched them sedulously for some clear determinative covering the degree of guilt for which Steven Maddren could lawfully be held responsible. At the end of three days of searching, the nearest she had come to it was a two-line insertion in the section dealing with Unconsummated crimes under the heading Incitement:

‘... incitement by one person or another to commit a crime, and conspiracy between two or more persons to commit a crime ...’

Abortion was a crime; Deborah had been incited to be a partner in that crime: Steven Maddren had conspired with her and with another – most likely a back-street doctor – to bring it about. Eloise marked the place with a green watered-silk ribbon and put the book to one side.

In another volume in the section given to the analysis of Joint Crimes, she read:

‘A principal in the first degree is a man who commits a crime or who induces its commission by some other person who himself does not understand what he is doing. In most cases of grave crime participants in a crime are equally guilty and liable to the same punishment ...’

Deborah’s punishment had been death so too must Steven Maddren’s punishment be death: he had induced the commission of a crime by some person who did not understand what she was doing: he was therefore a principal in the first degree: the Law said it.

And still she searched for a further finger of guilt and found under the classification Criminal Responsibility the ultimate indictment:

‘... it is now provided that a person who kills (or is a party to the killing of) another shall not be convicted of murder if he was suffering from such abnormality of mind as substantially impaired his mental responsibility ...’

Men whose minds were substantially impaired killed clumsily, personally and without thought of consequence, they did not make furtive appointments or pay out blood money, these were the acts of the thinking killer above and beyond any impairment of mind: he had known that the crime he instigated was against the law (a nicety of distinction not given to madmen), if he hadn’t actually killed he had been a party to the killing of ... and not being mad was therefore deserving of a conviction of murder: the Lord and the Law were on her side.

The books were now so much litter, and pushing free of them Eloise arose from her desk and, crossing the room, stood thoughtfully in front of a mullioned window beyond which an inquisitive bird with a limp worm in its beak stood looking in at her with a look of tiny surprise. She told it: ‘Let justice be done,’ and with a busy beat of its little wings it flew straight to the rooftop as if to broadcast the news.

Now that the obligation was confirmed there remained only the planning of his conviction. Nothing less than murder could get Steven Maddren the death penalty, and for that the Law would require a body (or clear evidence that there had been one) before charging, judging and passing sentence; and so ardently did Eloise Blassing yearn for Steven Maddren’s destruction that she seriously considered the sacrifice of herself. Death was death, and though able to be anticipated it could never be postponed; how very sensible then to die for a cause rather than as a result. But there was Anastasia, as equally grave a charge on her conscience as Deborah, dead. Anastasia was foolish, gullible, romantic and eager, a totally inadequate animal in an animal world: she could not be left alone in it. The choice was an unclouded one: either she, Eloise, must continue to live, or Anastasia must die with her.

The thought was not without compensation; the death of one lonely woman by foul play in a country house might, because of uncalculated influences, fail to bring the maximum penalty, but the deaths of two lonely ageing women by foul play must surely stifle any leaning to mercy in a conscientious jury.

Eloise did not think it in the realms of fantasy or beyond the bounds of possibility to believe that such a crime could be arranged ... and would be, she vowed, if a better solution did not present itself.

Chapter Three

FOR THE FIRST TIME IN HER LONG RETIREMENT ELOISE

went up to London and took Anastasia with her so that she, too, might have a taste of a forgotten world. It was, Eloise knew, the first cautious step in a series of steps that alone could bring about their slow and painful rehabilitation, without which no part of any plan eventually decided on could begin to succeed. Many times, throughout the morning Eloise realized just how sensible a move it was, as Anastasia, a compulsive gawper at any time, stopped abruptly at every store window they passed to feast her unbelieving eyes on the unbelievable merchandise of a world that had not stopped its clocks. And while the two emergent sisters observed the greatly changed London around them, London observed them right back, hardly daring to believe the identical, outdated pair passing it by, not knowing whether to smile on them indulgently or look at them askance.

In a West End post office Eloise consulted a directory for Steven Maddren’s place of business and any other pertinent information listed, jotting the information down in the classic script of her girlhood. That done she allowed herself time to look and listen and notice the passing of nearly all that had once made London familiar. The war had done much, she hadn’t known it could do so much. The lush Aladdined glass-fronted caves remained and the scarlet omnibuses prowling the constricted streets like lumbering land leviathans, other than those there was nothing to reduce the feeling of exile that filled her.

They walked up the Charing Cross Road into New Oxford Street and, making still another nostalgic turn into Gower Street, followed it through to a small back street in Euston where Steven Maddren’s business address was listed to be. She found his office at the top of a flight of wooden stairs, its door glossy with toffee-coloured varnish on which a paler wooden board with gold lettering grandly announced:

MADDREN ENTERPRISES:

BUSINESS PROMOTER & ROVING AGENT.

COMMISSIONS UNDERTAKEN –

ANYWHERE, ANY TIME.

Eloise did not enter, merely stood long enough to jot down the information in her book before returning to the street and Anastasia, obediently waiting where she had been left to wait, at the show window of a tucked away shop and a little dazed at the unglazed contemporary pottery on view, roughly surfaced and devoid of symmetry in a way meant to pass as crude primitive art; after the colour, the glaze and the elegance of the porcelain at Winton House, Anastasia thought it all very hopeless and intolerably ugly.

They retraced their steps to the wider, brighter part of Euston and into the Tottenham Court Road, where halfway along they found a little tea shop with impeccable white linen and pink silk lamps where Eloise ordered China tea for two and allowed Anastasia to choose two sickening tea-cakes from the trolley for herself.

They returned by a late afternoon train to Winton House, arriving at the tiny toy-town station a little before dusk, where a dutiful Bleecher stood waiting beside the Bentley and respectfully commented as he opened the limousine door for the sisters: ‘I trust you had a satisfactory day, Miss Eloise.’

‘It was not a disappointing day, thank you, Bleecher. You may drive a little faster tonight, both Miss Anastasia and myself are unusually tired.’