9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

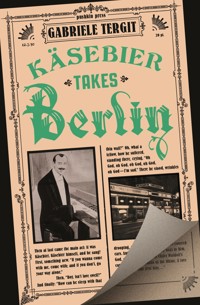

Fake news in Weimar Berlin: a blistering classic satire of journalism, lies and celebrity, in English for the first time In Berlin, 1930, the name Käsebier is on everyone's lips. A literal combination of the German words for "cheese" and "beer," it's an unglamorous name for an unglamorous man - a small-time crooner who performs nightly on a shabby stage for labourers, secretaries, and shopkeepers. Until the press shows up. In the blink of an eye, this everyman is made a star: one who can sing songs for a troubled time. All the while, the journalists who catapulted Käsebier to fame watch the monstrous media machine churn in amazement - and are aghast at the demons they have unleashed.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

TRANSLATOR’S INTRODUCTION

Käsebier Takes Berlin is a book about the power of the press. Not journalists or reporters, but the medium itself. Today, we might call it a tale of a story gone viral. In a week with no newsworthy stories, a journalist at a Berlin newspaper writes a short, throwaway article on an unknown popular singer, Georg Käsebier. But when the story is picked up by a famous poet and a young writer on the make, this nobody, whose name translates to “Cheese-Beer,” becomes Berlin’s new star, the everyman they’ve been looking for. Writers, photographers, movie makers, and bankers flock to Käsebier, hoping to convert his fame into reichsmarks. Berlin becomes a Käsebier economy. Yet fashion moves on quickly in the overheated capitalism of 1930s Berlin, and when Käsebier falls, many others fall too.

Though this novel is ostensibly about him, Käsebier is almost incidental to the story. The real protagonists of the book are the well-meaning journalists who unwittingly set off this fiasco. The writers at the Berliner Rundschau are a scrappy bunch of sleuths, critics, and know-it-alls dissecting and reporting on the world around them (though they can never publish the “really good stuff,” as they like to complain). When the Käsebier boom engulfs their own newspaper, they can only watch helplessly as they fall victim to their own creation.

Gabriele Tergit wrote Käsebier in 1931, but its depictions of fake news, sudden stardom, and bitter culture wars between left and right feel unnervingly contemporary. As she wrote, the Weimar Republic’s fragile parliamentary democracy was tumbling into dictatorship and Nazi terror. In only two years, she would have to leave the country, and would never live there again.

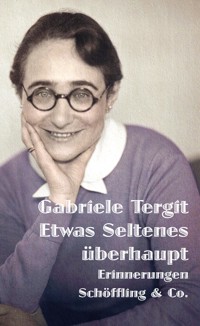

viii Tergit was born Elise Hirschmann, in Berlin, in 1894, into a family of successful Jewish industrialists. Ignoring protests from her bourgeois parents, Hirschmann became a journalist, writing under the pen name Gabriele Tergit. Today she is remembered as one of the few female writers of the New Objectivity movement, whose aim was to depict contemporary culture and society with cool dispassion. Within the writings of New Objectivity Käsebier stands out because it is a novel about the news, turning its eye on those who write about and reflect on events as they happen. Tergit’s voice is brisk, acerbic, and witty as she tells the story of a metropolis in upheaval. This translation of Käsebier brings this story, and Tergit’s trenchant brilliance and humor, to English readers for the first time.

In 1931, Tergit was at the height of her career, working as a journalist for the influential liberal newspaper Berliner Tageblatt. With her trademark round glasses, dark bob, and serious gaze, Tergit was a fixture of the Berlin literary scene, and could often be found at the Romanisches Café, the Café Adler, and the regulars’ table at Capri on Anhalter Strasse, just around the corner from Tageblatt headquarters. Tergit had spent most of her career as a court reporter, covering abortion trials, thefts, murders, bankruptcies, and political violence. Her interests ranged widely, though, and she wrote articles on women in the Weimar Republic, humorous essays on everyday life, and pieces for Carl von Ossietzky’s left-wing weekly Die Weltbühne. The publisher Rowohlt had just agreed to publish her first novel, Käsebier erobertden Kurfürstendamm, which would go on to be a hit. A year earlier, the Tageblatt had asked readers which public personalities the newspaper should profile. Alongside notables such as the poet Gottfried Benn and the cultural critic Oswald Spengler, they chose Tergit—the only woman featured.

It had taken willpower and hard work for such an unassuming woman to establish herself in the cutthroat newspaper world. Tergit published her first article at the age of nineteen, on women in the workforce. When she went to collect her pay, the editor exclaimed, ix “If I’d known you were so young, I wouldn’t have run the piece.” Tergit joined the staff of the Tageblatt in 1925 after cutting her teeth at the Berliner Börsen-Courier. Modest and sharp, she eschewed literary bravado for careful reporting and had a skeptical stance toward ideology, both right and left.

By early 1930, the economic depression and political instability was taking a toll on her career and family. Tergit’s salary at the Tageblatt had been reduced, and her husband, the architect Heinz Reifenberg, could only find occasional remodeling work. Her coverage of the Feme murders, assassinations committed by far-right paramilitary groups, had brought her the undesirable attention of the National Socialists. At five a.m. on March 4, 1933—the day before the federal election that brought Hitler to power—SA officers knocked at her door. Reifenberg told the maid not to open it, a choice that likely saved Tergit’s life. She quickly phoned a colleague with Nazi affiliations who pulled strings on her behalf to make the SA leave. She fled the following day to Czechoslovakia, while her husband and son remained behind in Berlin.

Tergit and her family spent the rest of their lives in exile, settling in London after several years in Palestine. She continued to write and publish as a freelancer, but never again found the audience of her prewar years. During and after the war she worked on Effingers, a novel in the spirit of Thomas Mann’s Buddenbrooks, portraying three generations of a Jewish family in fin de siècle Germany. Tergit considered it her magnum opus, though the book found little acclaim when it was published in 1951. In 1957, she became the secretary of the PEN Center for German Writers Abroad. Between the 1950s and the 1970s, she also wrote several successful books on the cultural history of flowers. This led her to comment sarcastically to a friend, “It seems that flowers are more popular than Jews.” To Tergit’s great disappointment, her third and final novel, So war’s eben, a social drama that begins in 1898 and ends in 1960s New York, never found a publisher.

Forgotten in her native country, Tergit was rediscovered in the 1970s, when Germans began to show interest in works written by x exiled authors. In 1977, Käsebier was republished and newly fêted by the press. At eighty-three, she reached her highest point of literary fame; her life’s work was celebrated at the Berliner Festwochen, a major annual cultural and literary festival, where she read from Käsebier to a captivated audience. Tergit died in London, at the age of eighty-eight, on July 25, 1982.

Käsebier Takes Berlin gives a view of the heady final years of the Weimar Republic from the inside of the newsroom. In 1930, Berlin had the greatest newspaper density of any European city: forty daily newspapers with a combined circulation of over three million copies. (The city itself had around four million inhabitants.) Competition was fierce, and newspapers engaged in bitter feuds, journalists raced one another to break stories, and publishers sold multiple daily editions and dozens of special-interest supplements to attract readers. The sheer volume and diversity of Berlin’s newspapers was overwhelming, yet many Berliners felt they could not afford to lag behind the never-ending stream of news. As Kurt Tucholsky writes in his satirical “Newspaper Reader’s Prayer,” “Dear Lord, please hear my prayer! Behold this stack, layer on layer! Dear Lord, I can’t take any more; here I have just one week’s score! And I have to read it all …”

Tergit’s Berliner Tageblatt was among the most important newspapers in the German capital and the country as a whole; as the flagship daily of Mosse, one of the big three Berlin publishers, it was the sixth-most-popular newspaper in Germany in 1930, with around 140,000 subscribers. During the Weimar years, the Tageblatt was also a significant voice of liberalism. Its editor in chief was Theodor Wolff, one of the “great men” of German journalism and a founder of the German Democratic Party, a left-of-center party committed to republican democracy. The GDP was largely made up of working professionals, and it was the party that most represented the interests of German Jews. The Tageblatt advocated for these politics and provided a strong voice in support of Germany’s fledgling democracy.

Tergit reported for the Berlin page of the Tageblatt along with xi two colleagues, Walther Kiaulehn and Rudolf Olden, with whom she formed a close-knit trio. The three friends embody the breadth and openneness of the intellectual scene of Berlin in the 1920s: Kiaulehn, who had worked as an electrician before joining the Tageblatt, came from a Prussian working-class family and held socialist sympathies; Olden had come to Berlin from Vienna, where he had already enjoyed a distinguished career working alongside Joseph Roth, Alfred Polgar, and Egon Erwin Kisch.

Tergit’s novel centers on the newsroom of the center-left BerlinerRundschau, a lightly fictionalized version of Tergit’s Tageblatt. Like the Tageblatt of the early 1920s, the Rundschau has a vibrant newsroom with a lively exchange of ideas, perspectives, and barbs. Both newspapers espouse progressive free-market positions, and have reporters who largely believe in the value of social democracy. But like the Tageblatt, which would face severe political and financial pressures in the late 1920s, the Rundschau ends up a splashy, slimmed-down version of itself—losing its credibility and public voice.

Kiaulehn and Olden, meanwhile, provided Tergit with inspiration for two of the book’s main characters: the cheery, sarcastic reporter Emil Gohlisch, and the verbose, intellectual editor in chief, Georg Miermann. Though Miermann was a composite figure, a paradigmatic example of the genteel, bourgeois intellectual, Olden spent weeks carrying a galley of Käsebier around under his arm, convinced he was its embattled protagonist. Like Miermann, Olden was a liberal editor with Jewish roots; unlike his fictional counterpart, who is steamrolled by political opportunists, Olden was outspoken, publishing strongly worded attacks against the German Right, including a 1932 book on conspiracy theories entitled Prophets in a German Crisis, and the damning 1935 biography Hitler the Pawn. Olden considered it his mission to be both an artist and a truth-seeker. He imbued every piece he wrote or edited with sharpness and clarity. In her autobiography, Tergit uses the same words to describe Olden’s editing that she had used decades earlier for the fictional Miermann: “He cut, reorganized, added punctuation, straightened out thoughts, lifted ideas out of the confusion of dim intuition and brought them into the xii clarity of enlightening prose, and only then did our articles become a good Kiaulehn, a good Tergit.”

When Tergit began writing Käsebier, the paper had undergone major changes. The newspaper had been significantly restructured by Hans Lachmann-Mosse, the son-in-law of the original founder, Rudolf Mosse. Lachmann-Mosse had taken over the reins of the Mosse empire in 1920, but lacked not only his father-in-law’s liberal convictions, but his business acumen as well. In the 1920s Lachmann-Mosse had undertaken a series of speculative investments, including a real estate development on a parcel of land long held by the family, which failed spectacularly (a central plot point in Käsebier).

By the late 1920s, staff salaries were low, as was morale. Theodor Wolff and Martin Carbe, the general director of the publishing company, frequently clashed with Lachmann-Mosse, who wanted to increase profits by taking direct control over the Tageblatt. By 1930, the Mosse empire was in peril. To save himself from ruin, Lachmann-Mosse drew money from employee pension funds and cut newspaper staff. Carbe resigned in protest and was replaced by Karl Vetter, a business-minded opportunist who reorganized the paper, added more illustrated supplements and lifestyle sections, and orchestrated large-scale advertising stunts. The Tageblatt became increasingly commercial, more entertainment than news.

In the federal election of September 14, 1930, the National Socialists increased their seats in parliament from 12 to 107. At first, many journalists doubted the Nazis would gain broader acceptance. The recognition of their error came too late, however, and soon the German liberal press lost its ability to intervene in the deteriorating political situation. After a string of failed cabinets, the German Democratic Party was dissolved, and a power vacuum emerged at the top of German government. Consensus on leadership was so difficult to achieve that by 1931 even newspapers critical of the Nazis had tempered their message, urging patience and cooperation with far-right politicians whom just two years earlier they had considered deeply repugnant.

The liberal press argued that Hitler should be included in the xiii government, in the hope that this might temper his party’s extremism. At the same time, journalists became increasingly fearful of repercussions for criticizing the Nazis or the army in print. What a few short years before had been a diverse and vibrant newspaper landscape was collapsing from within. On top of these internal problems, the ultranationalist Alfred Hugenberg had taken advantage of the economic instability caused by the Great Depression to buy up flagging newspapers across the country, including one of Berlin’s most popular dailies, the Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger, and built a powerful far-right media giant. Hugenberg’s company became the largest media corporation in Germany, one entirely at the service of the Right.

In this environment, the bustling world described by Tergit in her novel—the newsroom chatter, publishers’ gossip, animated meetings at the Romanisches Café—ground to a halt. At the Tageblatt, Theodor Wolff was reduced to one lead article a week and was asked by Lachmann-Mosse to desist from criticizing the cabinet led by Chancellor Heinrich Brüning. Tergit’s beloved editor, Olden, was dismissed in 1931, along with many longtime staff writers. Ultimately the war would separate Tergit from her colleagues too, both physically and ideologically: Tergit and Olden, both Jewish, and both politically undesirable, were forced into exile, where they continued to publish material against the Nazi regime. Kiaulehn remained, meanwhile, and while he initially received a professional ban from the Nazis, he later became a propaganda writer for the Nazis and an occasional announcer for the Deutsche Wochenschau, the newsreel of the Third Reich.

Along with the decline of the liberal press came a rise in anti-Semitism. The decline of the Berliner Tageblatt—tarred as a Judenblatt, or “Jewish paper”—was symptomatic of a broader cultural shift in which a liberal, cosmopolitan culture became displaced by a racist nationalist ideology. German Jews like Tergit, and her character Miermann, had made a home for themselves in modern Germany by adopting both German cosmopolitanism and a patriotism for the best of German culture. In Käsebier, Tergit shows the gradual exclusion of Jews from public life less through acts of overt anti-Semitism xiv than through an increasing devaluation of high culture, or Bildung, of which Jews were a prominent and visible part.

Late in the novel, Miermann wonders whether his family’s efforts to assimilate had been worthwhile. After walking past two Galician Jews with long beards and flowing caftans, he turns to ask his wife, “Have we become that much more beautiful, you with your blonde hair and blue eyes, and I with my books on romanticism and classicism?” An inextricable part of Miermann’s—and Tergit’s—German-Jewish identity is his love of Schiller, the liberal Romantic; Heinrich Heine, exiled Jewish poet and father of the feuilleton; and Anatole France, socialist progressive and defender of Zola in the Dreyfus Affair. Tergit believed that liberal thinkers were the spiritual fathers of the Weimar Republic, and remained the conscience of a nation that in the 1930s had lost the measure of things. Quotations from Schiller and Heine intersperse the novel as pointed references to a more civilized, open-minded time.

Tergit’s Jewish characters might not seem noticeably so to present-day readers, since they are neither portrayed differently nor perceive themselves as different from the German characters. Tergit felt it was not only clear who was Jewish, but worried her portrayals verged on the anti-Semitic. Käte Herzfeld and Reinhold Kaliski, for example, are both Jewish parvenu socialites who turn their social skill into financial success. When Käsebier was reprinted in 1977, Tergit tried to cut the subplot around Kaliski and change Käte’s last name to Brügger or Becker, fearing readers would find these characters unappealing. Her editors convinced her to leave the book untouched, however, leaving us with a picture of the social world of the 1920s in its original color.

The language of Käsebier is as colorful and varied as the world it portrays. Tergit’s book is not self-consciously experimental, but, as a product of New Objectivity, it easily moves between realism and modernism through its inclusion of fragmentary street scenes, headlines, snippets of songs, advertising slogans, and newspaper articles, xv as well as extended reflections on architecture, housing, work, and fashion. With each of these comes another register of language and particular vocabulary. Translating the novel meant following Tergit’s shifts from literary language to the most colloquial: a short conversation peppered with slang will be followed by a genteel description of an upscale apartment; the negotiation of a business contract will be interspersed with bawdy humor.

And, like all natives of the capital, Tergit has a love for Berlinerisch, the German spoken by the city’s inhabitants. Berlinerisch is sometimes crude and often cheeky, like the novel itself. It mixes cosmopolitan sophistication with earthy humor, and includes words from French, Flemish, Hebrew, Yiddish, and Rotwelsch, an argot used by beggars and thieves. Berlinerisch is well known for its creative insults and its characteristic sound, in which hard sounds become soft—“gut” becomes “jut” (pronounced: yoot)—and soft, hard—“Ich” becomes “Icke.” This translation attempts to convey the zip of Berlinerisch by using a combination of Anglo-American language of the era, everyday slang, and dropped consonants in colloquial speech. I deliberately chose this method over a distinct English dialect (for example, the slang of 1920s New York or London), which could distract from the novel’s geographic focus on Berlin. My goal has been to give an immersive sense of the world Tergit portrayed and try to relay the spark of Berlinerisch with a light hand.

Contemporary references have occasionally been glossed when they proved too obscure, but sometimes a gloss cannot re-create the same immediacy and urgency. For example, when Käte Herzfeld is asked how her love life is going, she responds somewhat cryptically, “Vertically excellent, so not taking bids on the horizontal”—yet her literal words are, “Vertically excellent, so horizontally crossed-out letter.” “Crossed-out letter,” or “gestrichen Brief,” refers to “-B,” financial shorthand for an exchange rate that has been cancelled because there are only offers but no demand. In a scant six words, Käte makes a sly but self-aware dig at the sexual mores and all-pervasive capitalism of the era. The phrase is gloriously precise and utterly peculiar; it shows Tergit’s journalistic knowledge of the floor of the stock exchange. xvi “Not taking bids” gets us only halfway there, but it is an attempt to uphold the spirit of the phrase, if not its specificity.

An important term that has no precise English equivalent is Käsebier’s métier: Volkssänger. While the literal translation is “folk singer,” a German “folk song” can include anything from a beer-hall schlager to a hiking song to a military melody or a show-tune. Käsebier conquers the hearts of Berliners because his songs, far from embodying the high ideals of Weimar cosmopolitanism and Bildung, are shallow and nostalgic throwbacks to the song traditions of Wilhelmine Germany, but even simpler, for the unsentimental, industrial present. But while his greatest hits—including “Boy, Isn’t Love Swell?” and “How Can He Sleep with That Thin Wall?”—elicit an easy attraction for Berliners, they are finally too superficial to last in the chaos of the early 1930s. They offer no solutions, just memories. Käsebier’s artistry is genuine, but it, too, gets swept away by events, and Käsebier ends his career in a shabby bar two hours outside Berlin.

Despite its ebullience and sprightly repartee, Käsebier is ultimately tragic. People lose their homes, their savings, and sometimes their lives. But along the way, the book also revels in the vitality and creativity of the people who made Weimar Berlin into a modern (and modernist) city. None of this was enough to ensure the survival of the liberal republic, of course, something Tergit knew when she was writing the novel. While she understood that this open, cosmopolitan Germany was still an unfulfilled vision rather than a reality, she saw in its spirit the best her country had to offer. It is this spirit that Tergit’s writing upholds—that of Minerva atop the crumbling newspaper headquarters.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Michael Brenner, The Renaissance of Jewish Culture in Weimar Germany (New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 1996)

Ursula Büttner, Weimar: Die überforderte Republik (Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, 2008)

Modris Eksteins, The Limits of Reason (London: Oxford University Press, 1975)

Ernst Feder, Cécile Lowenthal-Hensel, and Arnold Paucker (eds.) Heute sprach ich mit … : Tagebücher eines Berliner Publizisten,1926–1932 (Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1971)

Peter Fritzsche, Reading Berlin 1900 (London/Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996)

Bernhard Fulda, Press and Politics in the Weimar Republic (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009)

Peter Gay, Weimar Culture: The Outsider as Insider (New York: Norton, 2001)

Diethart Kerbs and Henrick Stahr (eds.), Berlin 1932: das letzte Jahr der ersten deutschen Republik (Berlin: Edition Hentrich, 1992)

Siegfried Kracauer and Tom Levin (trans. and ed.), The Mass Ornament (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995)

Wolf Lepenies, The Seduction of Culture in German History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006)

Peter de Mendelssohn, Zeitungsstadt Berlin (Berlin: Ullstein, 1959)

Georg Mosse, German Jews Beyond Judaism (Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press, 1985)

Juliane Sucker, “Sehnsucht nach dem Kurfürstendamm” (Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 2015)

Gabriele Tergit, Etwas seltenes überhaupt (Frankfurt a.M.: Ullstein, 1983)

Gabriele Tergit and Jens Brüning (ed.), Frauen und andere Ereignisse (Berlin: Das Neue Berlin, 2001)

Hans Wagener, Gabriele Tergit: gestohlene Jahre (Osnabrück: Universitätsverlag Osnabrück, 2013)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Books are never solitary endeavors; neither are translations. I owe a great deal of thanks to those who helped me make Tergit’s world come alive on the page in English. Thanks go to my editor, Edwin Frank, who took a chance on a translator who had yet to cut her teeth. I am grateful for the support of Shelley Frisch and Tess Lewis, who have been kind champions of my work and advisors in times of need. Thanks to the Goethe-Institut and the committee of the Gutekunst Prize, who helped me start my work as a literary translator and have continued to provide support since. A big thank-you to the friends who helped me work out problems and listened to my translational musings: Becky Fradkin, Abby Fradkin, Lois Beckett—your spirit helped me translate many a boozy dinner party conversation. Thanks also to Michael Swellander for his insights on Heine. Matthew Ward kindly helped me figure out some of the curiosities of Tergit’s German and smooth out my English. I am incredibly grateful to Michael Lesley for his voice, ears, and eyes, his creativity, energy, support, and perfectionism—thank you for throwing yourself into this with me, and making Käsebier as good as possible.

The biggest thanks go to my parents, Petra and Christian Duvernoy, who have been my editors, critics, and living encyclopedias for so many years. For Käsebier, my mother spent hours helping track down the meanings of period terms, deciphering Berlinerisch, and puzzling through countless odd phrases with great patience. My father, as always, pushed me to refine, check, and reflect on my own writing, and made sure my English sounded as close to Tergit’s German as possible.

I would like to dedicate this book to my grandparents, Hans and Christa Zehetmayer, and Wolf and Eva Duvernoy. They were witnesses to this time, and their stories are always with me. Though their lives, which would lead them to East Germany and Detroit, Michigan, respectively, could not have taken more different paths, they taught me about the complexities and realities of German history. This book is for them.

1

Nothing but slush

Berlin’s Kommandantenstrasse—half still the old newspaper district, half turning into the garment district—begins at Leipziger Strasse with a pleasant view over the trees of the Dönhoffplatz, now leafless, and disappears in the neighborhood of factories and workers on Alte Jakobstrasse.

Oh, Dönhoffplatz! On the right, the Tietz department store: Sale, Sale, Sale! Stiller’s Shoes: “Now Even Cheaper!” Umbrellas! They’re all there: Wigdor and Sachs and Resi. A blind man with newspapers squats in front of Aschinger’s distillery, waiting to snap a little something up. There’s the best store for artificial flowers. Boutonnières for suits in the spring, corsages for balls in the winter. Singers from Stettin! Invariably, a tall skinny one and a little fat one. Pastry shops, perfumes, suitcases, and woolens. So far, so good. The trouble begins on the first floor. Sales are slipping. Everything’s direct. Factory to retailer to consumer. If possible, straight from the factory to the consumer. That’s most of Donhöffplatz.

But over on the quiet side, almost by Kommandantenstrasse and its tiny, nameless shops, were the editorial offices of the Berliner Rundschau. The wide, long old house was four stories high, its corners topped with two large Greek amphoras. In the middle were two oversize plaster statues of Mercury and Minerva; between them stood a Roman shield. This house didn’t seem to have much business with Mercury these days. Half a floor was empty. It was unclear whether Miermann had joined the newspaper’s editorial staff because he had been seduced by Minerva, with her historical stone tablets, or because there were rose garlands hanging below the windows; either was 4 possible. What was clear, however, was that he had not been enticed by the baroque helmets with ostrich feathers that crowned the windows above, as he disliked military uniforms. A large golden date in the gable proclaimed that this exceedingly genteel house had been built in the year 1868.

Downstairs was a small café frequented mainly by journalists, which reeked of cigarette smoke and was badly ventilated through a small shaft that let out to the courtyard. The garbage bins sat directly underneath the shaft. The courtyard was so narrow that the sun barely reached the second floor. It was always dark in the café; only a few iridescent tulip lamps and dim electric bulbs lit the place. There were red marble tables, and small wooden chairs with cane backs and no armrests. But the owner was proud of having an intellectual clientele. He came from Vienna and thought highly of journalists. He knew each and every guest, and—more importantly—his articles.

At the top of the thoroughly worn-out stairs of the house was a glass box emblazoned with the word reception. In it sat a very young man. Beyond lay the editorial offices.

Emil Gohlisch, thirty years old, tall, pale, and blond, with extremely red hands, stood by the telephone. The editor, Miermann, some twenty years older than Gohlisch, sat at a desk. He had the breadth of an epic writer and the bleakness of a comedian. His collar permanently flaked with dandruff, and he never thought to wash his hands. He was an aesthete, but not when it came to himself. He somehow managed to pair a green tie with a purple suit, yet could tell just by touch whether a porcelain figure was from the 1730s or the 1780s. His parents had sent him away to apprentice as a salesman, which he couldn’t stand; his training was only useful insofar as it had expanded his horizons. Since he had never gone to grammar school, he couldn’t go to university. That was how he came to an art dealership, but he wasn’t particularly useful there either. He began to write. His family was glad that things hadn’t turned out even worse. Later, when he had made a name for himself—though he was still burdened with debt from earlier days—they even mustered up some pride. His two brothers were rather dull, a doctor and a lawyer who had married 5 money and championed Progress. They never said anything out of keeping, never uttered a phrase that wouldn’t have been said by anyone else in their generation. Gohlisch hung up the phone.

Miermann looked at the clock. “If my watch is still accurate,” he said, “tomorrow’s Thursday. I don’t have anything for Thursday’s page.”

“Someone should write about the new cafés sometime.”

“What use is sometime? Try today! Hic Rhodus, hic salta! Here’s Rhodes, here scatter your salt!”

“Let’s see if there’s anything.”

Miermann pulled a yellow folder with manuscripts out of a desk drawer. “There’s a good article on slush, but it’s still freezing. None of these people can write. No one can write a decent story. They don’t have any new ideas.”

“Someone should write about the bathroom situation in the Berlin schools sometime.”

“What am I supposed to run as the lead story tomorrow?”

Miehlke came in. He was the typesetter. Miehlke’s face was completely bare—no hair to be found anywhere on his face or head.

“G’day, gents. The page’s gotta be out by four thirty, it’s three now. Get to it. I’ve set the long article on the new construction work. If I take that one, the page’ll be full.”

“That’s far too long,” said Miermann shyly. He was bashful because Miehlke was the man who had once told the journalist Heye—Heye, who wrote the famous front-page editorials—“If you don’t cut this, Heye, I’ll cut twenty lines myself. You won’t believe how fast I can do that, and no one’ll notice.” And when Stefanus Heye smiled, Mielke added, “Maybe you think that one of your readers will notice? Eh, readers don’t notice nothin’, I tell ya. You gents always think something depends on it. Let me tell ya, nothin’ depends on it.”

“I don’t care,” Miehlke now said. “The paper can’t wait for you and cutting’s better than printing on the margins.”

Miehlke left.

“So, what shall we do?” asked Miermann.

“Well, I’m going to order coffee,” said Gohlisch.

Old Schröder came in. National desk. He still sported a full beard, 6 a green loden suit with horn buttons, and a wide black bow tie. “Things looked bad in the Reichstag today. I think the government’s collapsing, the Right’s on the rise. Just wait and see, they’ll pass all the taxes that they yelled at the Left over, no one but party members will get work, there will be pogroms, death sentences, and civil war. I know it. We’ll see something, all right; five battleships, subsidies to the German nationalists, we may as well pack up and go home.”

“I think they also put their trousers on one leg at a time,” said Miermann. “I know for a fact that the nationalists are just as corrupt as everyone else.”

“But Miermann! You have to admit that—”

“I never admit anything.”

“Sales taxes, just you wait, nothing but sales and excise taxes until our eyes bulge.”

“Maybe excise taxes are a good idea?”

“Miermann!” Schröder cried indignantly, “Be serious!”

“You ask too much of a man. I’m always supposed to get worked up: against sales taxes, for sales taxes, against excise taxes, for excise taxes. I’m not going to get worked up again until five o’clock tomorrow unless a beautiful girl walks into the room!”

“I should have been a political columnist. That old judge, now there was a man who knew every position, who had studied the whole state. Now we have a parliamentary system without a parliamentary commentator.”

Gohlisch got up. “Why bother? Breaking scandals sells more. Connections and a cushy little job. You’ve got a bee in your bonnet with your political commentator and your old judge. Put the headline in Borgis three bold. Here’s the coffee. Are you paying, Miermann, or is it my turn? I’ll pay.”

“What’s happening with the page?” said Miermann.

Schröder left. Gohlisch said, “Listen, Miermann, let me tell you a pretty little story. Just recently, there was a man who went from door to door, introducing himself to the Swiss presidents of big companies. He was their compatriot, a representative of Faber, asked them to purchase their supply of Faber pencils from him. So they 7 helped out their countryman, he went to Faber, bought leftovers, and sold crap for good money. One day, the boss asked for a pencil. He sharpened it, thought, hm, when the tip kept breaking off. Eventually, the affair came to light. The countryman was thrown out.

“You won’t believe,” Gohlisch said, “the things I learned on this trip. In Niedernestritz, the city council wanted to build a new town hall. Someone convinced the old servant he’d get a hundred marks, and the old dodderer, a slightly drunk figure who looks like a character out of Spitzweg,1 went over one night and built a pretty little fire in the basement. He didn’t skimp on gasoline or kindling, so the town hall burned and burned, the firefighters were only called in the morning—the servant hadn’t noticed, after all—he implored them not to use too much water, and the building burned merrily to the ground. But now the servant was only going to be paid fifty marks for his troubles. Naturally, he was very upset, and went to the insurance company to tell them that he’d set the fire and was prepared to go to jail, but he’d never suffered such an injustice as with these fifty marks. The insurance company had already noticed that they were dealing with arson, with a nice, well-made fire. But they hadn’t been able to sell any insurance in Niedernestritz or the surrounding area for the past fifteen years. They were quite pleased with the fire, since once people noticed how nice the new city hall the insurance company was building looked, they all got insured; it was practically raining insurance applications. The insurer was delighted; so was the city council, and everyone was happy.”

“That’s a nice story. Maybe the insurance company also paid the city council a little something, how about that?”

“That happened in Niedernestritz, but of course you can’t write about that. You can never write about the really good stuff.”

“Good story, but what are we going to do about the page?”

“I have an idea. An acquaintance recently told me about a popular cabaret: supposed to be a great singer there in Hasenheide, got to check it out.”

“I’ve only got bad manuscripts; Szögyengy Andor’s written about ‘The Last Horse-Cart Driver’ again …” 8

“What pests, these professional Hungarians!” said Gohlisch.

“There’s been an article on weekend outings lying around since September, good article, but since I’ve gotten it there’s been nothing but bad weather, so I can’t use that. You can’t run an article on weekends when it’s so cold. You just can’t.”

Miehlke came in again. “Well, what’m I supposed to do, gents, the page has to be out by four thirty. I’ll take the construction and cut it myself if you gents won’t deliver. Like I said, nothing depends on it.”

Miermann sat there, resigned. “All right, we’ll take the construction piece, but we’ll have to cut half of it. Gohlisch, you always leave me hanging. When will we run the article on the singer?”

“Next Wednesday, for sure. Upon my soul!”

“Well, that’s something! When you say Wednesday in eight days, I can be certain that you mean Wednesday in eight months.”

“I can’t work on command, it has to come to me. I’m not a fountain pen. I’m a steadfast servant of thought.”

“If it thaws next Wednesday, we’ll run the slush article; otherwise, yours.”

“Done.”

“But I need to be able to rely on you. That page is getting worse by the week. You writers are out of good ideas, and we aren’t getting any submissions. There’s no talent.”

“That’s true,” said Gohlisch, “but only because the untalented writers are popular and cheaper. A big shot publisher recently said that the worse newspapers are, the more they sell. What’s talent good for? No talent plus a dash of sadism sells a lot more. A rape is more popular than a sentence by Goethe, although Goethe’s still acceptable. Briand sat at the desk of the Petit Journal for over a decade and told people stories. That’s how his newspaper got started. He never wrote a line himself. He was paid a handsome salary, and that’s how Briand was made. But publishers haven’t got a clue about the business of writing.”

And with that, they vanished into the composing room.

2

Once again, nothing comes of the slush story

It was even colder the following Wednesday.

“Have we ever had a winter like this?” asked Gohlisch. “If we still had one of my articles lying around on frost and ice or frozen lakes in the Mark, it would surely thaw. Here’s the article. I’m going to order coffee now. Cake? No cake?”

“Cake,” said Miermann.

“My dear Miermann,” exclaimed Herzband the writer, who went by Lieven, as he burst into the room with outstretched hands, his cloak aflutter. “What do you have to say about that most exquisite piece Otto Meissner wrote about me?”

“I can say I read the lovely piece that you wrote about Otto Meissner,” said Miermann.

“I can’t ignore that your answer was meant to cut me to the quick. I admit that I’m vain to an almost ungodly degree. But can’t friends praise friends? I ask you: shouldn’t friends praise friends? Please, I ask you: isn’t it one’s duty to forge camaraderie in resistance to this world, inartistic as it is, bereft of gods? We few, creative, intellectual thinkers? The writer should praise his comrade, since only the like-minded can recognize one another! Have you already read my book, dearest Miermann, Dr. Buchwald Seeks His Path? Not yet? A political novel of the highest caliber! Nothing less, I assure you, dear editor, nothing less is offered than the solution to foreign affairs. I’ll send it to you. The writer must be a traveling salesman for his own books, the writer must manage his own reputation since his fame furthers that of the nation. The writer’s vanity is justified, and nothing can harm his stature more than if he looks upon the intellectual trade with scorn! 10 Think: my books have been translated into every culturally significant language, even Irish. Recently, I had a four-hour-long conversation with Bratianu on a trip to Bucharest. ‘I’ve just read,’ he said, ‘a very beautiful novel by a German writer named Lieven.’ I stood up and bowed. ‘I am that very man.’ What a moment! What an experience! What joy! Bratianu read a German novel; Bratianu loved this novel; Bratianu loved this novel’s author; I am that author! So, dear Miermann, so as not to take up any more of your precious time, I ask you to run a notice regarding an event of European import: the great French lawyer and poet Paul Regnier has asked me to write a play with him on the trial of the Soviet saboteurs. I have accepted his request. We will begin our work shortly. This is the first sign of Franco-German cooperation on a European theme. In a few words, I have sketched the importance of this event. Here they are. An international item. Please place it in the evening paper straight away.”

Gohlisch had, in the meantime, been looking out the window.

What a strange store over there, he thought. For years it had been a clothing store, but now it’s disappeared, like all the clothing stores. Recently, at Hausvogteiplatz, an old lady said to me, “Isn’t it awful, now D. Lewin’s gone too. I’ve been buying my coats at Manheimer’s for forty years. I just came in to the city from Karlshorst to buy myself a coat. V. Manheimer’s gone. I think to myself, I’ll go to D. Lewin. Lewin’s gone as well.” It was almost like the revolution, people spoke to each other on the street for no reason. Then the store became a wine shop. Germans drink German wine, but eventually they also began to sell Bordeaux and all kinds of schnapps. Six bottles of wine for five marks; even that was too much for people. Beer’s cheaper. Then came a store for kitchen furnishings. All sorts of kitchen furnishings. Eschebach’s Kitchen Units, three smooth cupboards next to one another, bottomless glass drawers; next to them, tasteful antique cupboards in carved wood or colored glass. Furniture stores don’t work. A person needs rent, gas, electricity, heating, and food—lots of food—fresh food three times a day, but he can walk around in the same coat for years and get his kitchen cupboards at the flea market. The kitchen store vanished as well, thought Gohlisch, and a restaurant 11 sprang up, but there are too many restaurants in the neighborhood. Good wine restaurants; Aschinger’s, free bread, forty-five pfennigs for a sausage, peas with bacon for seventy-five pfennigs; then there’s the old Münze, a beer restaurant, excellent; a kosher restaurant, separate meat and veg; lots of bakeries. Far too many restaurants in the neighborhood. New ones can’t compete. The restaurant disappeared and the storefront stood empty again until another restaurant took its place. Young plucky things who stuck a pickled herring in the window.

“You’re not interested in literature,” Lieven said venomously, addressing the back of Gohlisch’s head. Gohlisch was still looking out the window.

“Oh, certainly, but only good literature,” said Gohlisch. “Karl May, or Buried in the Desert, or things like that. By the way, there’s nothing doing with the slush,” he added in Miermann’s direction.

Miermann understood, and said to Lieven, “Excuse us, we have to put together a newspaper. Unfortunately, we’re just honest workers. Not free spirits, but servants to the publisher. Obedient slaves to the public. I’m very interested in your book. No doubt I’ll read it.”

Lieven bowed, put on his big, floppy hat, his cloak flying. “I bestow my greetings upon the men of the world,” he said.

“He’s really gone soft in the head,” said Gohlisch. “You only hear things like this about that man: ‘Mr. Adolf Lieven will write a drama that takes place among artists.’ No scenes, no title, no plot. Just ‘artists.’ Then they begin sending out press releases. ‘Mr. Adolf Lieven announces that his book, The Lame Vulture, will be translated into new Siberian.’ Mr. Adolf Lieven was received by the president of Argentina during his South American research trip. We don’t get news like that from Gerhard Hauptmann. But what will we do about Thursday’s page? Thank God, coffee. Say, girl, don’t catch a cold without your coat. Are you paying, Miermann, or is it my turn?”

“I’m paying this time,” said Miermann. “The slush isn’t going to work. The streets are disgustingly clean. But the slush has to come one day, otherwise, where’ll we get our spring from? I also have an article on marriage statistics.”

12 “That’ll fill a box, but you can’t lead with it.”

“I just received a lead article, a pleasant piece from Szögyengy Andor on the different ways that Berliners spend their Sundays.”

“These professional Hungarians again! Why don’t you take a look at my article on the singer, I don’t think it came out very well, it didn’t really come together—I’m not feeling that great anyways, I’m going to order a schnapps. D’you want one too?”

“Does a man stand on one leg?” said Miermann.

Gohlisch went to the phone and ordered two glasses of grappa.

Suddenly, there was a loud noise in the hall. The door flew open, and a scent wafted in; first the scent, then a very large woman. She wore a very thick, loose fur coat made of light brown bearskin, a thin, bright yellow dress underneath, out of which peeked a pair of long, shapely, pink-tinged legs. A yellow, brown, and red scarf fluttered around her neck. She wore a bright red beret perched atop many very blonde curls. The beret was set far back on her head, crooked and to the right. She was heavily made up, which only accentuated her gaudy appearance. She was young, and had a wily face. With a great din, she suddenly stood in the small room that was already packed with two desks. An engraving of the Forum Romanum hung on the wall above Miermann’s desk. Gohlisch had tacked up a watercolor of a sailboat he had painted over his desk. She looked around for a second, then ran toward Miermann, who had jumped up. She put her arms around his shoulders, kissed him, and cried, “God, Miermann, my darling, I haven’t seen you in ages, what’s wrong with us? Here!” She pressed a manuscript into his hand. “Print it, sugar lips, print it! Don’t you remember?”

“Of course, dear,” said Miermann. “The Academy Ball, four thirty, second closet, fourth corridor.”

She was out again in a flash. Gohlisch yelled, “I’m an honest republican from the clan of the Verrinas,” and banged his fist on the table.2 “Are you acquainted with that Kurfürstendamm slut?”

“No clue,” said Miermann. “I only know who she is.”

In that moment, a big blond man came in: Öchsli the theater critic. “What the hell was that?” he cried. “All of a sudden a gal came 13 sweeping down the hallway, called out, ‘Sweet Öchsli, haven’t seen you for ages, d’you still remember?’ But I don’t remember anything.”

“That happened to me too. She’s not a friend, but I know who she is. That was Aja Müller. She has one car, two poodles, and two relationships: one with the playwright Altmann and another with the son of a director at the D-Bank.”

“Must be quite nice sleeping with her,” Gohlisch replied, and continued writing.

“The things she writes are quite nice too,” said Miermann. “Snobby, but not too snobby given the topic. Parties and balls. I’ll give it straight to the setter, since I don’t have a lead. Maybe you can rework the thing on Käsebier.”

“I’ll see. By the way, the place was completely packed. Not a seat in the house, even at six thirty. A pair of acrobats performed, a lot better than in the big vaudeville shows. Käsebier is excellent. It’s worth it. He sings with a partner, also very good, by the way, traditional songs from the Rhine, unbelievably kitschy. One was especially good, the story of a tenement, ‘How Can He Sleep with That Thin Wall?,’ quite excellent. And then he plays the pimp.” Gohlisch picked up a scarf and took a few steps, soft and fresh. “Passage Friedrichstrasse, under the lindens green.” He raised his chin, thrust out his lower lip, and raised his open hand to his face, jerking it once, twice, to indicate business. “I’m pretty sure that there’s room for a thousand people in there. It’s quite a thing with the acrobats; a man walking on a tightrope is already enough for me. But apparently that isn’t enough. He also has to play the fiddle while he’s doing it. It’s a very strange thing: music as an accompaniment to a display of human agility. Plus an excellent clown; he wanted to sit on a chair but it was all wobbly, and he couldn’t get it to stand straight. He took out a big cigar box and with a great deal of difficulty broke it into little pieces, deadly serious. Finally, he ended up with a piece small enough to shove under the leg of the chair, but it kept slipping away. All of our male gravity, gone up in smoke. The tricky business of preventing a chair from wobbling that still wobbles. I’m going to get some breakfast.”

“You lack ambition,” Miermann said.

14 “Ambition? For lead articles?” asked Gohlisch. “No, I don’t have any. I don’t try; I want to be asked.”

“You’re being asked.”

“No, I’m not. I know only smooth talkers make it around here.”

Miermann laughed. Gohlisch went to breakfast at a Hungarian place on Kommandantenstrasse. The place was decorated in white, red, and green, like a Hungarian country tavern. Ears of corn hung from individual booths, and the whole place was garlanded with corncobs. The booths were brightly painted and looked like rustic canopy beds, with four wooden pillars holding up the roof. Dr. Krone was sitting in one of them.

“Greetings, sir,” said Gohlisch—then a conspiratorial figure who published unsavory exposés in various newspapers and magazines under the byline ‘Augur’ came creeping in. He carried twelve newspapers under his arm, kept his head down and his eyes up. Gloomily, without a word, he shook everyone’s hand. The three gentlemen ordered a bottle of Tokay.

“What have you got, sir?” Gohlisch asked Dr. Krone, who hadn’t opened his mouth.