1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

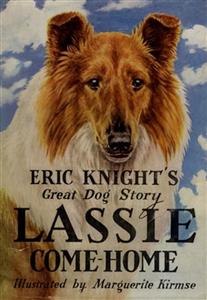

In "Lassie Come-Home," Eric Knight crafts a poignant narrative that captures the bond between a young boy, Joe, and his loyal Rough Collie, Lassie. Set against the backdrop of the English countryside during the interwar period, Knight employs a straightforward yet evocative literary style that effectively conveys themes of loyalty, courage, and the profound connection between humans and animals. The novel's episodic structure allows readers to engage deeply with both the emotional and physical landscapes that Joe and Lassie navigate in their quest to reunite, symbolizing resilience and hope amidst adversity. Eric Knight, an American author and playwright, was influenced by his own experiences growing up in Yorkshire, England. His affection for dogs and nature permeates his writing, reflecting a deep appreciation for the bond shared between humans and their animal companions. "Lassie Come-Home" was inspired by Knight's childhood encounters with a collie, and his own nostalgia and longing for connection drive the narrative, elevating it to an exploration of love, sacrifice, and the instincts that bind us. This timeless classic is a must-read for anyone who cherishes stories of companionship and adventure. Knight's engaging storytelling will resonate not only with lovers of animals but also with readers seeking an uplifting exploration of loyalty and the intrinsic value of relationships. Through the heartwarming journey of Joe and Lassie, readers are invited to reflect on the enduring power of love and the lengths one will go to for those they cherish.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

Lassie Come-Home

Table of Contents

1

CHAPTER ONE

Not for Sale

Everyone in Greenall Bridge knew Sam Carraclough’s Lassie. In fact, you might say that she was the best-known dog in the village—and for three reasons.

First, because nearly every man in the village agreed she was the finest collie he had ever laid eyes on.

This was praise indeed, for Greenall Bridge is in the county of Yorkshire, and of all places in the world it is here that the dog is really king. In that bleak part of northern England the dog seems to thrive as it does nowhere else. The wind and the cold rains sweep over the flat moorlands, making the dogs rich-coated and as sturdy as the people who live there.

The people love dogs and are clever at raising them. You can go into any one of the hundreds of small mining villages in this largest of England’s counties, and see, walking at the heels of humbly clad workmen, dogs of such a fine breed and aristocratic bearing as to arouse the envy of wealthier dog fanciers from other parts of the world.

And Greenall Bridge was like other Yorkshire villages. Its men knew and understood and loved dogs, and there were many perfect ones that walked at men’s heels; but they all agreed that if a finer dog than Sam Carraclough’s tricolor collie had ever been bred in Greenall Bridge, then it must have been long before they were born.

But there was another reason why Lassie was so well known in the village. It was because, as the women said, “You can set your clock by her.”

That had begun many years before, when Lassie was a bright, harum-scarum yearling. One day Sam Carraclough’s boy, Joe, had come home bubbling with excitement.

“Mother! I come out of school today, and who do you think was sitting there waiting for me? Lassie! Now how do you think she knew where I was?”

“She must have picked up your scent, Joe. That’s all I can figure out.”

Whatever it was, Lassie was waiting at the school gate the next day, and the next. And the weeks and the months and the years had gone past, and it had always been the same. Women glancing through the windows of their cottages, or shopkeepers standing in the doors on High Street, would see the proud black-white-and-golden-sable dog go past on a steady trot, and would say:

“Must be five minutes to four—there goes Lassie!”

Rain or shine, the dog was always there, waiting for a boy—one of dozens who would come pelting across the concrete playground—but for the dog, the only one who mattered. Always there would be the moment of happy greeting, and then, together, the boy and the dog would go home. For four years it had always been the same.

Lassie was a well-loved figure in the daily life of the village. Almost everyone knew her. But, most of all, the people of Greenall Bridge were proud of Lassie because she stood for something that they could not have explained readily. It had something to do with their pride. And their pride had something to do with money.

Generally, when a man raised an especially fine dog, some day it would stop being a dog and instead would become something on four legs that was worth money. It was still a dog, of course, but now it was something else, too, for a rich man might hear of it, or the alert dealers or kennelmen might see it, and then they would want to buy it. While a rich man may love a dog just as truly as a poor man, and there is no difference in them in this, there is a difference between them in the way they must look at money. For the poor man sits and thinks about how much coal he will need that winter, and how many pairs of shoes will be necessary, and how much food his children ought to have to keep them sturdy—and then he will go home and say:

“Now, I had to do it, so don’t plague me! We’ll raise another dog some day, and ye’ll all love it just as much as ye did this one.”

That way, many fine dogs had gone from homes in Greenall Bridge. But not Lassie!

Why, the whole village knew that not even the Duke of Rudling had been able to buy Lassie from Sam Carraclough—the very Duke himself who lived in his great estate a mile beyond the village and who had his kennels full of fine dogs.

For three years the Duke had been trying to buy Lassie from Sam Carraclough, and Sam had merely stood his ground.

“It’s no use raising your price again, Your Lordship,” he would say. “It’s just—well, she’s not for sale for no price.”

The village knew all about that. And that was why Lassie meant so much to them. She represented some sort of pride that money had not been able to take away from them.

Yet, dogs are owned by men, and men are bludgeoned by fate. And sometimes there comes a time in a man’s life when fate has beaten him so that he must bow his head and decide that he must eat his pride so that his family may eat bread.

2

CHAPTER TWO

“I Never Want Another Dog”

The dog was not there! That was all Joe Carraclough knew.

That day he had come out of school with the others, and had gone racing across the yard in a rush of gladness that you see at all schools, all the world over, when lessons are over for the day. Almost automatically, by a habit ingrained through hundreds of days, he had gone to the gate where Lassie always waited. And she was not there!

Joe Carraclough stood, a sturdy, pleasant-faced boy, trying to reason it out. The broad forehead above his brown eyes became wrinkled. At first, he found himself unable to realize that what his senses told him could be true.

He looked up and down the street. Perhaps Lassie was late! He knew that could not be the reason, though, for animals are not like human beings. Human beings have watches and clocks, and yet they are always finding themselves “five minutes behind time.” Animals need no machines to tell time. There is something inside them that is more accurate than clocks. It is a “time sense,” and it never fails them. They know, surely and truly, exactly when it is time to take part in some well-established routine of life.

Joe Carraclough knew that. He had often talked it over with his father, asking him how it was that Lassie knew when it was time to start for the school gate. Lassie could not be late.

Joe Carraclough stood in the early summer sunshine, thinking of this. Suddenly a flash came into his mind.

Perhaps she had been run over!

Even as this thought brought panic to him, he was dismissing it. Lassie was far too well-trained to wander carelessly in the streets. She always moved daintily and surely along the pavements of the village. Then, too, there was very little traffic of any kind in Greenall Bridge. The main motor road went along the valley by the river a mile away. Only a small road came up to the village, and that became merely narrow footpaths farther along when it reached the flat moorland.

Perhaps someone had stolen Lassie!

Yet this could hardly be true. No stranger could so much as put a hand on Lassie unless one of the Carracloughs were there to order her to submit to it. And, moreover, she was far too well known for miles around Greenall Bridge for anyone to dare to steal her.

But where could she be?

Joe Carraclough solved his problem as hundreds of thousands of boys solve their problems the world over. He ran home to tell his mother.

Down the main street he went, racing as fast as he could. Without pausing, he went past the shops on High Street, through the village to the little lane going up the hillside, up the lane and through a gate and along a garden path and then through the cottage door, to cry out:

“Mother? Mother—something’s happened to Lassie! She didn’t meet me!”

As soon as he had said it, Joe Carraclough knew that there was something wrong. No one in the cottage jumped up and asked him what the matter was. No one seemed afraid that something dire had happened to their fine dog.

Joe noticed that. He stood with his back to the door, waiting. His mother stood with her eyes down toward the table where she was setting out the tea-time meal. For a second she was still. Then she looked at her husband.

Joe’s father was sitting on a low stool before the fire, his head turned toward his son. Slowly, without speaking, he turned back to the fire and stared into it intently.

“What is it, Mother?” Joe cried suddenly. “What’s wrong?”

Mrs. Carraclough set a plate on the table slowly and then she spoke.

“Well, somebody’s got to tell him,” she said, as if to the air.

Her husband made no move. She turned her head toward her son.

“Ye might as well know it right off, Joe,” she said. “Lassie won’t be waiting at school for ye no more. And there’s no use crying about it.”

“Why not? What’s happened to her?”

Mrs. Carraclough went to the fireplace and set the kettle over it. She spoke without turning.

“Because she’s sold. That’s why not.”

“Sold!” the boy echoed, his voice high. “Sold! What did ye sell her for—Lassie—what did ye sell her for?”

His mother turned angrily.

“Now she’s sold, and gone, and done with. So don’t ask any more questions. They won’t change it. She’s gone, so that’s that—and let’s say no more about it.”

“But Mother ...”

The boy’s cry rang out, high and puzzled. His mother interrupted him.

“Now no more! Come and have your tea! Come on. Sit ye down!”

Obediently the boy went to his place at the table. The woman turned to the man at the fireplace.

“Come on, Sam, and eat. Though Lord knows, it’s poor enough stuff to set out for tea ...”

The woman grew quiet as her husband rose with an angry suddenness. Then, without speaking a word, he strode to the door, took his cap from a peg, and went out. The door slammed behind him. For a moment after, the cottage was silent. Then the woman’s voice rose, scolding in tone.

“Now, see what ye’ve done! Got thy father all angry. I suppose ye’re happy now.”

Wearily she sat in her chair and stared at the table. For a long time the cottage was silent. Joe knew it was unfair of his mother to blame him for what was happening. Yet he knew, too, that it was his mother’s way of covering up her own hurt. It was exactly the same as her scolding. That was the way with the people in those parts. They were rough, stubborn people, used to living a rough, hard life. When anything happened that touched their emotions, they covered up their feelings. The women scolded and chattered to hide their hurts. They did not mean anything by it. After it was over ...

“Come on, Joe. Eat up!”

His mother’s voice was soft and patient now.

The boy stared at his plate, unmoving.

“Come on, Joe. Eat your bread and butter. Look—nice new bread, I just baked today. Don’t ye want it?”

The boy bent his head lower.

“I don’t want any,” he said in a whisper.

“Oh, dogs, dogs, dogs,” his mother flared. Her voice rose in anger again. “All this trouble over one dog. Well, if ye ask me, I’m glad Lassie’s gone. That I am. As much trouble to take care of as a child! Now she’s gone, and it’s done with, and I’m glad—I am. I’m glad!”

Mrs. Carraclough shook her plump self and sniffed. Then she took her handkerchief from her apron pocket and blew her nose. Finally she looked at her son, still sitting, unmoving. She shook her head sadly and spoke. Again her voice was patient and kind.

“Joe, come here,” she said.

The boy rose and stood by his mother. She put her plump arm around him and spoke, her head turned to the fire.

“Look Joe, ye’re getting to be a big lad now, and ye can understand. Ye see—well, ye know things aren’t going so well for us these days. Ye know how it is. And we’ve got to have food on the table and we’ve got to pay our rent—and Lassie was worth a lot of money and—well, we couldn’t afford to keep her, that’s all. Now these are poor times and ye mustn’t—ye mustn’t upset thy father. He’s worrying enough as it is—and—well, that’s all. She’s gone.”

Young Joe Carraclough stood by his mother in the cottage. He did understand. Even a boy of twelve years in Greenall Bridge knew what “poor times” were.

For years, for as long as children could remember, their fathers had worked in the Wellington Pit beyond the village. They had gone on-shift, off-shift, carrying their snap boxes of food and their colliers’ lanterns; and they had worked at bringing up the rich coal. Then times had become “poor.” The pit went on “slack time,” and the men earned less. Sometimes the work had picked up, and the men had gone on full time.

Then everyone was glad. It did not mean luxurious living for them, for in the coal-mining villages people lived a hard life at best. But it was a life of courage and family unity, at least, and if the food that was set on the tables was plain, there was enough of it to go round.

Only a few months ago, the pit had closed down altogether. The big wheel at the top of the shaft spun no more. The men no longer flowed in a stream to the pit-yard at the shift changes. Instead, they signed on at the Labor Exchange. They stood on the corner by the Exchange, waiting for work. But no work came. It seemed that they were in what the newspapers called “the stricken areas”—sections of the country from which all industry had gone. Whole villages of people were out of work. There was no way of earning a living. The Government gave the people a “dole”—a weekly sum of money—so that they could stay alive.

Joe knew this. He had heard people talking in the village. He had seen the men at the Labor Exchange. He knew that his father no longer went to work. He knew, too, that his father and mother never spoke of it before him—that in their rough, kind way they had tried to keep their burdens of living from bearing also on his young shoulders.

Though his brain told him these things, his heart still cried for Lassie. But he silenced it. He stood steadily and then asked one question.

“Couldn’t we buy her back some day, Mother?”

“Now, Joe, she was a very valuable dog and she’s worth too much for us. But we’ll get another dog some day. Just wait. Times might pick up, and then we’ll get another pup. Wouldn’t ye like that?”

Joe Carraclough bent his head and shook it slowly. His voice was only a whisper.

“I don’t ever want another dog. Never! I only want—Lassie!”

3

CHAPTER THREE

An Evil-tempered Old Man

The Duke of Rudling stood by a rhododendron hedge and glared about him. He lifted his voice again.

“Hynes!” he roared. “Hynes! Where has that chap got to? Hynes!”

At that moment, with his face red and his shock of white hair disordered, the Duke looked like what he was reputed to be: the worst-tempered old man in all the three Ridings of Yorkshire.

Whether or not he deserved this reputation, it would seem sufficient to say that his words and actions earned it.

Perhaps it was partly due to the fact that the Duke was exceedingly deaf, which caused him to speak to everyone as if he were commanding a brigade of infantry on parade, as indeed he had done, many years ago. He had also a habit of carrying a big blackthorn walking stick, which he always waved wildly in the air in order to give emphasis to his already too emphatic words. And finally, his bad temper came from his impatience with the world.

For the Duke had one firm belief: which was that the world was going, as he phrased it, “to pot.” Nothing ever was as good these days as it had been when he was a young man. Horses could not run so fast, young men were not so brave and dashing, women were not so pretty, flowers did not grow so well, and as for dogs, if there were any decent ones left in the world, it was because they were in his own kennels.

The people could not even speak the King’s English these days as they could when he was a young man, according to the Duke. He was firmly of the opinion that the reason he could not hear properly was not because he was deaf, but because people nowadays had got into the pernicious habit of mumbling and snipping their words instead of saying them plainly as they did when he was a young man.

And, as for the younger generation! The Duke could—and often would—lecture for hours on the worthlessness of everyone born in the twentieth century.

This last was curious, for of all his relatives, the only one the Duke could stand (and who could also stand the Duke, it seemed) was the youngest member of his family, his twelve-year-old granddaughter, Priscilla.

It was Priscilla who came to his rescue now as he stood, waving his stick and shouting, beside the rhododendron hedge.

Dodging a wild swish of his stick, she reached over and pulled the pocket of his tweed Norfolk coat. He turned with bristling moustaches.

“Oh, it’s you!” he roared. “It’s a wonder somebody finally came. Don’t know what the world’s coming to. Servants no good! Everybody too deaf to hear! Country’s going to pot!”

“Nonsense,” said Priscilla.

She was indeed a very self-contained and composed young lady. From her continued association with her grandfather, she had grown to consider both of them as equals—either as old children or as very young grownups.

“What’s that?” the Duke roared, looking down at her. “Speak up! Don’t mumble!”

Priscilla pulled his head down so that she could speak directly into his ear.

“I said, Nonsense!” she shouted.

“Nonsense?” roared the Duke.

He stared down at her, then broke into a roar of laughter. He had a curious way of reasoning about Priscilla. He was convinced that if Priscilla had pluck enough to answer him back, she must have inherited it from him.

So the Duke felt in a much better temper as he looked down at his granddaughter. He flourished his long white moustaches, which were much grander and finer than the kind of moustaches that men manage to grow these days.

“Ah, glad you turned up,” the Duke boomed. “I want you to see a new dog. She’s marvellous! Beautiful! Finest collie I ever laid my eyes on.”

“She isn’t so good as the ones they had in the old days, is she?” Priscilla asked.

“Don’t mumble,” roared the Duke. “Can’t hear a word you say.”

He had heard perfectly well, but had decided to ignore it.

“Knew I’d get her,” the Duke continued. “Been after her for three years now.”

“Three years!” echoed Priscilla. She knew that was what her grandfather wanted her to say.

“Yes, three years. Ah, he thought he’d get the better of me, but he didn’t. Offered him ten pounds for her three years ago, but he wouldn’t sell. Came up to twelve the year after that, but he wouldn’t sell. Last year offered him fifteen pounds. Told him it was the rock-bottom limit—and I meant it, too. But he didn’t think so. Held out for another six months, then he sent word last week he’d take it.”

The Duke seemed pleased with himself, but Priscilla shook her head.

“How do you know she isn’t coped?”

This was a natural question to ask, for, if the truth must be told, Yorkshiremen are not only knowing about raising dogs, but they are sometimes alleged to carry their knowledge too far. Often they exercise devious secret arts in hiding faults in a dog: perhaps treating a crooked ear or a faulty tail carriage so that this drawback is absolutely imperceptible until much later, when the less knowing purchaser has paid for the dog and has taken it home. These tricks and treatments are known as “coping.” In the buying and selling of dogs—as with horses—the unwritten rule is caveat emptor—let the buyer beware!

But the Duke only roared louder when he heard Priscilla’s question.

“How do I know she isn’t coped? Because I’m a Yorkshireman, too. Know as many tricks as they do, and a few more to boot, I’ll warrant.

“No. This is a straight dog. Besides, I got her from Whatsisname—Carraclough. Know him too well. He wouldn’t dare try anything like that on me. Indeed not!”

And the Duke swished his great blackthorn stick through the air as if to defy anyone who would have the courage to try any tricks on him. The old man and his grandchild went down the path to the kennels. And there, by the mesh-wire runs, they halted, looking at the dog inside.

Priscilla saw, lying there, a great black-white-and-golden-sable collie. It lay with its head across its front paws, the delicate darkness of the aristocratic head showing plainly against the snow-whiteness of the expansive ruff and apron.

The Duke clicked his tongue, in signal to the dog. But she did not respond. There was only a flick of the ear to show that the dog had heard. She lay there, her eyes not turning toward the people who stood looking at her.

Priscilla bent down and, clapping her hands, called quickly:

“Come, collie! Come over here! Come see me! Come!”

For just one second the great brown eyes of the collie turned to the girl, deep brown eyes that seemed full of brooding and sadness. Then they turned back to mere empty staring.

Priscilla rose.

“She doesn’t seem well, Grandfather!”

“Nonsense!” roared the Duke. “Nothing wrong with her. Hynes! Hynes! Where is that fellow hiding? Hynes!”

“Coming sir, coming!”

The sharp, nasal voice of the kennelman came from behind the buildings, and in a moment he hurried into sight.

“Yes, sir! You called me, sir?”

“Of course, of course. Are you deaf? Hynes, what’s the matter with this dog? She looks off-color.”

“Well, sir, she’s a poor feeder,” the kennelman hurried to explain. “She’s spoiled, Hi should say. They spoils ’em in them cottages. Feeds ’em by ’and wiv a silver spoon, as ye might say. But Hi’ll see she gets over it. She’ll take her food kennel way in a few days, sir.”

“Well, keep an eye on her, Hynes!” the Duke shouted. “You keep a good eye on that dog!”

“Yes, sir. I will, sir,” Hynes answered dutifully.

“You’d better, too,” the Duke said.

Then he went muttering away. Somehow he was disappointed. He had wanted Priscilla to see the fine new purchase he had made. Instead, she had seen a scornful dog.

He heard her speaking.

“What did you say?”

She lifted her head.

“I said, why did the man sell you his dog?”

The Duke stood a moment, scratching behind his ear.

“Well, he knew I’d reached my limit, I suppose. Told him I wouldn’t give him a penny more, and I suppose he finally came to the conclusion that I meant it. That’s all.”

As they went together back toward the great old house, Hynes, the kennelman, turned to the dog in the run.

“Hi’ll see ye eat before Hi’m through,” he said. “Hi’ll see ye eat if Hi ’ave to push it down yer throat.”

The dog gave no motion in answer. She only blinked her eyes as if ignoring the man on the other side of the wire.

When he was gone, she lay unmoving in the sunshine, until the shadows became longer. Then, uneasily she rose. She lifted her head to scent the breeze. As if she had not read there what she desired, she whimpered lightly. She began patrolling the wire, going back and forth—back and forth.

She was a dog, and she could not think in terms of thoughts such as we may put in words. There was only in her mind and in her body a growing desire that was at first vague. But then the desire became plainer and plainer. The time sense in her drove at her brain and muscles.

Suddenly, Lassie knew what it was she wanted. Now she knew.