10,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: And Other Stories

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

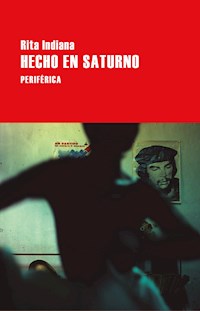

These are the children of revolutions, and this is their story. This is the Caribbean. This is Argenis Luna: an artist who no longer paints, a heroin addict who no longer uses, and an overgrown child trying to make sense of his inheritance in a country where his once-revolutionary father is now part of the ruling elite. Thrown out of rehab in Havana, with Goya's tyrannical god Saturn on his mind, Argenis picks his way through the detritus of an abandoned generation: the drag queens, artists, hustlers and lovers trying to build lives amidst the wreckage. Mesmerising and visionary, Made in Saturn is a hangover from a riotous funeral, a rapid-fire elegy for the revolutionary spirit, and a glimpse of hope for all who feel eclipsed by those who came before them.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 241

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

First published in English in 2020 by And Other Stories Sheffield – London – New York www.andotherstories.org

First published as Hecho en Saturno by Editorial Periférica in 2018 Copyright © Rita Indiana c/o Schavelzon Graham Agencia Literaria, 2020 English-language translation © Sydney Hutchinson, 2020

All rights reserved. The right of Rita Indiana to be identified as author of this work and of Sydney Hutchinson to be identified as the translator of this work has been asserted.

ISBN: 9781911508601 eBook ISBN: 9781911508618

Editor: Bella Bosworth; Copy-editor: Gesche Ipsen; Proofreader: Sarah Terry; Typesetting and eBook: Tetragon, London; Cover design: Steven Marsden.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

And Other Stories gratefully acknowledge that our work is supported using public funding by Arts Council England.

In memory of Milagros Dottin

Contents

Made in SaturnNote to the ReaderCurrent and Upcoming BooksAbout the Author and TranslatorCome down off your throne and leave your body alone Somebody must change You are the reason I’ve been waiting so long Somebody holds the key Well, I’m near the end and I just ain’t got the time And I’m wasted and I can’t find my way home.

‘Can’t Find My Way Home’, Blind Faith

Made in Saturn

Doctor’s office light. Dull light, wet behind a hood of clouds that sank the shoulders of the horizon. Dull, like the orthopaedic shoes of Dr. Bengoa, like the folder on which the doctor had written the name of his new patient, Argenis Luna, who was just coming off a Cubana Airlines flight, dizzy and dripping a pasty, cold sweat. Bengoa was waiting for him on the tarmac in his wrinkled, champagne-colored guayabera shirt, both hands on a sign whose bold letters he had filled in impeccably.

As soon as he recognized Argenis, the doctor came over to take his pulse while looking at his wristwatch. As they walked down the tarmac to pick up his bags he introduced him to the young soldier escorting them, saying, “This is the son of José Alfredo Luna.” The palm trees defied the lightning’s flashes against the gray background of the clouds, and in spite of his malaise Argenis thought it was beautiful. The air was charged and he breathed with difficulty, his nose running like an open faucet. Now at the baggage carousel, Bengoa spoke again to the soldier, adding, “My comrade José Alfredo is a hero of the Dominican urban guerrilla war and a student of Professor Juan Bosch.”

Argenis’s bags dropped out onto the carousel just as Bosch surfaced into the conversation. They rode all the way around before he could be bothered to identify them, before he could be bothered to interrupt Bengoa. The heroic attributes Dr. Bengoa was listing orbited eternally around his father’s legend, and Argenis along with them, just another satellite, like the red fabric suitcases on the belt. He had no strength to grab them, full as they were of the stuff his mother had bought to outfit his detox treatment in Cuba. He pointed them out with his finger and pulled the hood of his jacket up to combat the air-conditioning and the embarrassment of his obvious weakness. For months he had been living on the sofas of those friends who could still stand him, his only property a green Eastpak backpack he used to hold his syringes, his spoon, and a Case Logic full of CDs. His mother had thrown everything into the trash except the CDs and the backpack, which now held a bottle of Barceló Imperial rum as a gift for Dr. Bengoa and a big box of Frosted Flakes.

The young soldier helped them carry the bags to the car, the muscles of his lower arms barely contracting from the weight of the luggage. He feigned enthusiasm for Bengoa’s topic and looked at Argenis out of the corner of his eye, as if trying to find something of the heroic father in the 120 pounds of skin and bones his son amounted to that spring.

From far away Dr. Bengoa’s brick-red Lada looked new, but now inside, suffering a chill of the sort that precedes diarrhea, Argenis calculated the real age of the car by the cracks in the dashboard. He had gone forty-eight hours without heroin and had thrown up in the airplane. The Cuban flight attendants with their anachronistic uniforms and hairstyles had seemed as absurd to him as the Alka-Seltzer tablets they offered to relieve his symptoms.

Dr. Bengoa opened the glove compartment with a whack of his hand and extracted a disposable needle, some cotton, a length of rubber, and a strip of amber-colored capsules that said “Temgesic 3mg.” The strip fell onto Argenis’s lap and for the first time he noticed the dirt that had accumulated on his jeans. They were the same ones he had been wearing a little less than a month ago when he moved into his pusher Rambo’s house.

As he tied the rubber strap around Argenis’s left arm to make the vein pop out, Dr. Bengoa explained the details of his stay, and then, pushing the syringe into the ampoule, he said, “It’s buprenorphine, a synthetic morphine used to treat addiction.” Bengoa injected him right there in the José Martí airport parking lot, with all the tranquility and legality his profession permitted, and Argenis let him do his job like a girl in love while taxi drivers in Cadillacs from a bygone era came and went, full of nostalgia tourists. Argenis had assumed that his treatment would be one of pain and abstinence, but there he was on his way to La Pradera, a hotel-turned-clinic for the health tourists who came to Cuba from all over the world, completely relieved of his symptoms and feeling how the chemical made ideas and objects lose their borders, their sharp edges.

From the outside at least, the complex looked like a cheap all-inclusive resort, one of the ones that fill up with middle-class families during Holy Week in Puerto Plata. The walls along the hallway to the reception area were decorated with posters of communist solidarity. Argenis tried unsuccessfully to imagine a hotel like this in the Dominican Republic. Colorful prints with maps and flags representing the various peoples of the world paid homage to the medical profession as a revolutionary bastion. On one of them, orange liquid from an immense syringe was being injected into a map of Latin America, with Haiti as the fortunate vein. At any other time Argenis would have made a joke.

Right in front of the injection poster, an older woman with an Argentine accent was asking a nurse for information about Coppelia, the ice-cream parlor, and next to her a younger woman who resembled her sat in a wheelchair, hiding the baldness of chemotherapy under a Mickey Mouse cap. Haydee, as the ID badge clipped to the nurse’s shirt read, was not in uniform but was wearing those rubber-soled shoes that only gardeners or health professionals wore back then – everything-proof moccasins that had come from outside the country, the product of a night spent with a European, a satisfied patient’s appreciation, or the guilty conscience of a sister exiled in Miami.

The nurse watched Bengoa with smiling complicity as she told the women about the history of the famous ice-cream parlor. She pulled a heavy wooden key ring with the number nineteen painted on it from her pocket and handed it to the doctor, saying “the lock has a trick to it,” before helping the Argentines into a taxi.

The new chemical was entering his system to the hurried rhythm of Bengoa’s conversation: a torrent of dates emblematic of the anti-imperialist struggle; recipes for detox shakes; bits of songs by Silvio, Amaury Pérez, and Los Guaraguao; the Chinese economy; and baseball statistics. His mouth was dry and his pupils so dilated that everything around him was starting to look like a high-contrast photo. He held on to the doctor’s arm as they walked around the pool to room nineteen. The room, which Bengoa had called a privilege, had a view of the pool and a sliding glass door, in front of which two men, one in pajamas and the other in a bathing suit, were playing cards at a little wrought-iron table topped with plastic flowers. The doctor struggled with the lock, unable to hit on the trick Haydee had mentioned, while Argenis took stock of the furnishings of his new room through the glass: a ceiling fan, twin beds, a nightstand.

The door to his pusher Rambo’s house also had a trick to it: you had to pull on it as you inserted the key. “Let me try,” he said to Bengoa, and the doctor moved aside, satisfied with the noticeable improvement in his new patient. Argenis tried once, twice, wiggling the key in the lock like the tail of a happy dog until the door gave way and the smell of bleach and clean sheets hit them in the face.

Privilege. He could feel the word in his mouth, as it made the same movements it would make to taste and swallow a spoonful of frosting. He said it every morning after brushing his teeth and washing his face, as he put on the tiny Speedos his mother had picked out. Then he would swim a bit, not very athletically, doing a few laps of breaststroke. Bengoa had prescribed it to stimulate his appetite and it was working. Around eight a.m., Haydee would bring a tray of fried eggs, toast, and coffee that he’d scarf down in his room without being able to avoid thinking about the people outside the clinic, people who mainly breakfasted on a watery coffee of chickpeas and old grounds.

“Eat it all up, Argenis,” Haydee would tenderly request as she filled her bag with paper from the bathroom trashcan to throw out. Argenis wondered if Haydee lived in La Pradera or if she took the patients’ leftovers home every night. Her rubber-soled shoes were as hygienic as they were discreet and they didn’t reveal much beyond the work that allowed her to have them. They would never let on what Haydee thought of the foreigners whose dollars gave them access to places and services Cubans couldn’t even dream of. According to Bengoa, Argenis wasn’t in La Pradera because of the dollars his dad had sent along with him in a diplomatic pouch on the Cubana Airlines flight, but rather because of his father’s revolutionary credentials, his political career, the expanding orbit of his attributes.

After breakfast, he would read a bit at the iron table from a coverless copy of Asimov’s Foundation and Empire which Bengoa had brought, and a half-hour later he’d be in the water again. Arms spread like a cross, his back to the edge of the pool, he would bicycle his legs and watch how the hospital awoke little by little, how the ill would emerge from their rooms with lazy eyes and feet. He amused himself by thinking that the hotel was an old movie he was projecting with the movements of his legs underwater, and he would slow the bicycle down as if it was a crank that would make the scenes go by in slow motion. He always achieved the desired effect; it was a simple trick, since everyone in La Pradera moved as slow as hell.

If it was really sunny the pool would fill up by about ten a.m. and Argenis would get out, afraid of contracting some strange disease, or rather another disease, because Bengoa had made him see that he was sick, that addiction was a physical condition and that he was there to cure it. He would be cured of shooting up, although addiction itself had no cure. “Your brain will always have that hunger, that thirst for relief,” Bengoa had said, as he handed Argenis a pack of Popular cigarettes.

Bengoa and Argenis had lunch together every day and they would smoke at the iron table before and after the meal, observing the staff giving a blond boy with Down syndrome water therapy. They would discuss Argenis’s symptoms and then the doctor would return to the gravitational center of all his conversations, the Cuban Revolution. Bengoa had been in the mountains with Fidel and had met Argenis’s father during the Latin American Solidarity Conference of 1967. He would speak of these events with the solemnity of a preacher, highlighting dates and the names of forgotten places where he’d cured the wounds, fevers, infections, and asthma of the revolutionaries’ flesh. Each day Bengoa would extract a sample from his bottomless sack of anecdotes. Most of these memories were as precise as Argenis’s dose of buprenorphine, and it was obvious that they filled the doctor with the same kind of calm that the medicine gave his patient. Remembering these events and their sensations, Bengoa’s pupils would dilate, his pulse accelerate, and then the inevitable comedown would make him stare at the pool water and throw out a last, usually tragic, line to ease his forced landing just a bit.

“When your dad came I met Caamaño, who was training here so that he could sacrifice himself in the DR later on.”

Argenis imagined the word “sacrifice” beating in Caamaño’s veins and those of his companions, the dark euphoria that had made them disembark on a boggy beach on the Dominican Republic’s north coast in 1973 in order to topple Balaguer’s government with just nine men. A tremendous high. Cuba and its revolution had pricked their veins and those of millions of young people around the world.

When Bengoa finished his daily historical venting, it was usually just before four p.m., the time when, without fail, he would inject Argenis in his room. He could have done it by the pool, but Argenis preferred to lie down on the bed for a bit, looking at the ceiling fan or at a transfer of an Argentine flag someone had stuck onto the sliding door. Argenis had thought the flag was an allusion to Che Guevara, but Bengoa explained proudly that Maradona had once stayed in that clinic and pointed out the sticker as irrefutable proof of the star’s past presence. The sticker had started to peel off and air pollution had tinted the transparent edges the same amber color as the Temgesic capsules.

Argenis had never been good at packing suitcases, which might seem strange for a professional painter with a fine arts education and a proven talent for composition, perspective, and proportion. For him, transferring objects from the world or from his imagination onto canvas in a balanced way had always been a natural inclination, even before his artistic training. When he was little he would draw his classmates’ heads during the Spanish class he hated, achieving a realism so effective that his mom raced to sign him up for lessons with the master painter Silvano Lora. Silvano had been one of his parents’ comrades in arms in the seventies and his exile during Balaguer’s twelve years in power had been one of the topics of the article for which the journalist Orlando Martínez had been assassinated. “Orlando Martínez died so that people like you and Silvano could be free today,” Etelvina had told him as they were waiting for Silvano to open the door of his studio.

Like Bengoa, Argenis’s mom was a natural-born storyteller, but unlike the doctor, her memories of that era brought her little comfort. Instead they made her speak slowly and painfully, in the rhythm of someone drinking a bitter tonic.

Order and cleanliness were the only weaknesses Argenis had been able to detect in his mother. The last time she had taken him into her house, after his divorce from Mirta, he had dared to say that her desire for pulchritude was merely a Trujillist relic. Etelvina refused to speak to him for three years – until the night when, having dragged Argenis out of his pusher’s apartment by force, José Alfredo had left him in her house. She had made him swallow a sedative without water and he’d awoken on her sofa twelve hours later with his stomach turning from the smell of salami being fried up for breakfast. There were two red fabric suitcases open in the middle of the living room which Etelvina was filling with clothing, tins of food, and toiletries. “Where are you going?” Argenis asked, and she looked at him, glad to see him awake, wearing an expression of tenderness he hadn’t seen on her face since he was a boy.

Just hours before Bengoa picked Argenis up from La Pradera to take him to the apartment he’d rented for him in Havana’s Chinatown, Argenis’s clothes, which had arrived in Cuba as orderly as a good game of Tetris, had been strewn all around the room: on the bed, on the floor, falling out of drawers, and untidily hung over the towel rod in the bathroom. He was too lazy to pick them up. He was too lazy for anything. He was wearing the same old pink rubber flip-flops from his pusher’s house. His new shoes, leather moccasins and a pair of sneakers, were still in one of the suitcases. The second suitcase, which contained cans of food and Nesquik, was still locked.

Argenis’s grandmother Consuelo, his father’s mom, had folded many more shirts and pants than Etelvina had, and not for her good-for-nothing kids, but because she had worked as a servant for more than forty years. Reflecting on those numbers, Argenis decided to fold a few items in her honor. He gathered up his things and threw them on the bed, but as he looked at the pile of dirty clothes he saw his grandmother as the Little Prince on a tiny planet of stinking clothing and dirty dishes, fighting against other people’s grease, her eternal baobab. The apathy came over him again, a profound feeling of sloth, a tiredness of the world in general. “My grandmother has folded enough clothes,” he thought, as if the old woman’s years of hard work had exonerated him from doing the same. That exoneration, bought with Argenis’s grandmother’s sweat, was the excuse he used for spending every day he was married to Mirta watching porn on the internet and snorting coke, then his preferred drug, while his now ex-wife put in her nine-to-five in the Banco Hipotecario.

Argenis felt for the pack of cigarettes in his pants pocket. That rectangular bulge in his jeans calmed him a bit. He rolled everything into a big ball and stuffed it into the suitcase, pulled the zipper up with some difficulty, and went outside to smoke a Popular. It was not yet ten a.m., and after three weeks of treatment the mornings were often pitted by brief yet recurrent feelings of unease which Argenis calmed by silently repeating, “Bengoa will be here soon.” If he had been under the effects of Temgesic, he’d at least have folded a shirt or two. Temgesic makes everything interesting, even dirty clothes.

Bengoa arrived and Argenis noticed that he wasn’t wearing the little fanny pack with the syringes, cotton, alcohol, rubber, and vials. By way of a greeting, Argenis nervously asked, “Is the treatment already over, asere?” With a half-smile, the doctor wheeled his cases toward the car under a sun that made his bald head glisten and answered, “Now that you’re going to have your own place, you’ll be injecting yourself.” When they got to the car, he handed over a box filled with twelve 3mg vials, and Argenis couldn’t remember ever having been so happy in his whole life.

On their drive, Havana was looking glorious and desperate, an old woman with legs open, brazenly displaying her wide and empty streets – streets that reminded Argenis of an amusement park; no cars, buses, or trams. The people who were coming and going wore an anguish on their faces he could recognize as his own: it was the anguish of having to hustle for everything on the black market, just as he’d hustled for heroin in Santo Domingo.

The routine at La Pradera had been good for him. He felt strong and self-sufficient. “This is a new era,” he told himself. As he helped to take the suitcases out of the trunk, he was conscious of the eight pounds of muscle mass he’d gained thanks to Bengoa’s attentions. The renewed capabilities of his body surprised him as they carried the bags upstairs together. As if going through a second puberty, his insides swelled with something resembling the awkward happiness he’d felt when his childish cheeks were newly populated with dark hairs.

The uneven beard that had started to grow when he was thirteen was his first triumph over his brother Ernesto, who at fifteen already had two definite callings: kissing their dad’s ass and making Argenis’s life impossible. Ernesto was the best student in his year, besides being class president, and he had already had a couple of girlfriends. But that summer, while Argenis stood in front of the bathroom mirror trying out shaving with his mother – since José Alfredo had already left them for Genoveva – his older brother’s hairless white face was colonized by the nastiest acne case in history. Traces of blood and pus stained every pillow in the house.

Their father had boasted a splendid beard from a young age. He proudly pointed it out whenever he showed them pictures from his militant stage: pictures of him at protests sporting an untrimmed Afro and thick-rimmed sunglasses. He was a different person back then, a person who knew less than Argenis did about the dark phenomena that would turn him into the hypertensive, clean-shaven, permanently suited guy who defended his party, the Dominican Liberation Party, in the newspapers.

The paint on the stairs going up to Argenis’s new home was surrendering to the extreme humidity. Flakes of it hung down like the petals of an enormous funeral flower. The bronze spiral bannister decorated in art nouveau motifs had been recently polished, although here and there pieces had been hacked off by some thief or other. When they reached the fifth floor, his T-shirt soaking wet, Argenis felt like a man again and not like the shadow that had loomed over the untidy property of his best friends for the last few months.

From the apartment’s entryway you could see a balcony about three meters long, and a lovely breeze was blowing in from it. He dropped his bags and walked over to see if the view of decrepit buildings, rooftops, and laundry lines had the same contagious harmony as the rest of Havana. It wasn’t his first time in the city. In 1992 he had come to a summer camp for young revolutionaries from all over Latin America. His impression then had been the same as now: a heartbreaking mix of need and beauty. Standing out on the apartment’s balcony, he felt like a humble eighth note in a grandiose symphony whose sounds, audible only to the soul, greatly surpassed the appearance of its score of colonial architecture, dirty water, and ideology.

Standing with him on the balcony, Bengoa was speechifying on the history of the neighborhood, on Chinese immigration, on the old folk who used to stand in their doorways smoking opium – stories that he would embellish when he felt they were too short in the telling. Then he drew a little map of the best restaurants, in case Argenis wanted to blow the twenty bucks he was going to leave him, and Argenis supposed that, just as he had considered it appropriate to trust him with the administration of his own medicine, the doctor would eventually let him manage the money his dad sent, too.

Bengoa had equipped the kitchen with coffee, sugar, bread, eggs, rice, and a couple of potatoes, stuff he pointed out while opening the cabinets with the smiling gestures of a magician showing the inside of a box in which his assistant has been pierced by swords. Then he showed him the apartment’s two bedrooms, and Argenis mentally converted one of them into a painting studio. He saw himself there looking robust and inspired, putting the finishing touches to a monochromatic nude of a headless woman.

“Can I trust you?” Bengoa asked, passing him a key chain sporting a cheap medal of the Virgen de la Caridad del Cobre, and Argenis said yes, of course.

With difficulty, Argenis waited for four p.m., the time the doctor had indicated he should inject himself. To deal with the anxiety, he eyed the vial that was lying on the decorative flowers of the rattan sofa in the living room, smoked a Popular, and drank the coffee he had made in the blue greca pot that came with the kitchen. The coffee came from one of the five packages of Café Santo Domingo that Etelvina had put in the suitcase. Each time he saw them he loudly asked, “Why didn’t you also pack me five cartons of Marlboro Lights?” as if his mother could hear him.

When only a few minutes remained, he sat down on the rattan sofa and laid all his instruments out on the coffee table. It was all much easier now that there was nothing to light. He put the needle into the vial and filled the syringe.

Bengoa hadn’t left him the rubber strap, so he took off his belt, and as he tied it around his bicep the Janet Jackson song “Escapade” emerged from some place in the building. Its first notes, in this setting strange and at the same time familiar, made Argenis think about the Cubans’ obsession with eighties’ synthesizers, those bland keyboards that for them are the essence of modernity, the things with which Phil Collins and Peter Gabriel made millions.

Millions.

With the relief the injection brought, he savored the idea for the first time. If he had millions, he would buy all the heroin he’d need for the rest of his life. The purest goddamn smack in the world. He would live a tranquil life, not bothering anyone, disciplined and satisfied with his daily ration of happiness, as triumphant as a worker on a Soviet poster, a syringe in one fist and a giant spoon in the other.

The Bible says that God saw man was lonely, so he made him a woman from his own flesh. Argenis’s father, lacking such superpowers, sent him a boom box with a CD player. Bengoa brought it over, and Susana with it, “to clean your apartment.” Susana had curly dark brown hair, a perfect belly button, and beautiful toes with pink polish peeking through her plastic sandals. She had brought a cheap cloth apron, which she put on immediately in order to attack the dirty dishes piled up in the sink. The water made refreshing sounds as it splashed on the plates, though Bengoa insisted on interrupting them with his praise of Sony, the makers of the boom box.

“This is what I call aerodynamic design, Argenis. If you don’t want it, I’ll take it,” he said with childlike enthusiasm as he plugged the apparatus in and stuck his hand without permission into the Case Logic, which was lying on the counter. He rooted around until he found a CD by Joan Manuel Serrat that Argenis never played but which the doctor apparently loved. Then he sat on one of the rocking chairs and took a swig from the flask of Havana Club he always had in his back pocket, and which he’d sometimes used to spike their coffees at La Pradera.

Susana was cleaning Argenis’s room with a broom and a mop she had found in the kitchen. He could hear her clanking around in the closet and prayed she wouldn’t find any dirty underwear that hadn’t made it to the laundry basket. Bengoa, now standing in front of Argenis, took another swig from his bottle, grimaced, and then puckered his lips as for a kiss, looked toward the room where Susana was working and, while pushing his fat middle finger in and out of the circle he’d made with his other hand, said loudly enough for Susana to hear, “Susana studied art history, Argenis. You’ll get along very well.”