9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

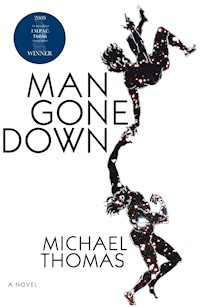

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

On the eve of this thirty-fifth birthday, the unnamed black narrator of Man Gone Down finds himself broke, estranged from his white wife and three children, and living in the bedroom of a friend's six-year-old child. He has four days to come up with the money to keep his kids in school and make a down payment on an apartment for them to live in. As we slip between his childhood in inner city Boston and present-day New York City, we discover a life marked by abuse, abandonment, raging alcoholism, and the best and worst intentions of a supposedly integrated America. This is a story of the American Dream gone awry, about what it's like to feel preprogrammed to fail in life and the urge to escape that sentence.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

MAN GONE DOWN

MAN GONE DOWN

Michael Thomas

First published in the United States of America in 2007 by Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

This paperback edition published in Great Britain in 2009 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd. Copyright © Michael Thomas 2007. All rights reserved.

The moral right of Michael Thomas to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-84887-243-1

eISBN: 978-0-85789-532-5

Printed in Great Britain.

Atlantic Books An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd Ormond House 26-27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Part I: The Loser

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Part II: Big Nig

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Part III: Evening’s Empire

Chapter 15

Part IV: Everybody Is a Star

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Acknowledgments

For Michaele— My wife, my love, my life: the one. Everything is for you.

We proclaim love our salvation …

—Marvin Gaye

I

The Loser

If you came at night like a broken king.

–T. S. Eliot, “Little Gidding” I

1

I know I’m not doing well. I have an emotional relationship with a fish—Thomas Strawberry. My oldest son, C, named him, and that name was given weight because a six-year-old voiced it as though he’d had an epiphany: “He looks like a strawberry.” The three adults in the room had nodded in agreement.

“I only gave you one,” his godfather, Jack, the marine biologist, told him. “If you have more than one, they kill each other.” Jack laughed. He doesn’t have kids. He doesn’t know that one’s not supposed to speak of death in front of them and cackle. One speaks of death in hushed, sober tones—the way one speaks of alcoholism, race, or secret bubble gum a younger sibling can’t have. Jack figured it out on some level from the way both C and X looked at him blankly and then stared into the small aquarium, perhaps envisioning a battle royal between a bowlful of savage little fish, or the empty space left behind. We left the boys in their bedroom and took the baby with us. “They don’t live very long,” he whispered to us. “About six weeks.” That was C’s birthday in February. It’s August, and he’s not dead.

He’s with me on the desk, next to my stack of books and legal pads. I left my laptop at my mother-in-law’s for C to use. She’d raised an eyebrow as I started to the door. Allegedly, my magnum opus was on that hard drive—the book that would launch my career and provide me with the financial independence she desired. “I write better if the first draft is longhand.” She hadn’t believed me. It had been a Christmas gift from Claire. I remember opening it and being genuinely surprised. All three children had stopped to see what was in the box.

“Merry Christmas, honey,” she’d cooed in my ear. She then took me by the chin and gently turned my face to meet hers. “This is your year.” She kissed me—too long—and the children, in unison, looked away. The computer was sleek and gray and brimming with the potential to organize my thoughts, my work, my time. It would help extract that last portion of whatever it was that I was working on and buff it with the requisite polish to make it salable. “This is our year.” Her eyes looked glazed, as though she had been intoxicated by the machine’s power, the early hour, and the spirit of the season. It had been bought, I was sure, with her mother’s money. And I knew Edith had never believed me to have any literary talent, but she’d wanted to make her daughter feel supported and loved—although she probably had expected it to end like this. C had seemed happy when I left, though, sitting on the floor with his legs stretched under the coffee table, the glow from the screen washing out his copper skin.

“Bye, C.”

“By-ye.” He’d made it two syllables. He hadn’t looked up.

Marco walks up the stairs and stops outside his kid’s study, where I’m working. He knocks on the door. I don’t know whether to be thankful or annoyed, but the door’s open and it’s his house. I try to be as friendly as I can.

“Yo!”

“Yo! What’s up?” He walks in. I turn halfway and throw him a wave. He comes to the desk and looks down at the stack of legal pads.

“Damn, you’re cranking it out, man.”

“I’m writing for my life.” He laughs. I don’t. I wonder if he notices.

“Is it a novel?”

I can’t explain to him that three pads are one novel and seven are another, but what I’m working on is a short story. I can’t tell him that each hour I have what I believe to be an epiphany, and I must begin again—thinking about my life.

“Want to eat something?”

“No thanks, man, I have to finish this part.”

I turn around on the stool. I’m being rude. He’s moved back to the doorway, leaning. His tie’s loose. He holds his leather bag in one hand and a fresh beer in the other. He’s dark haired, olive skinned, and long nosed. He’s five-ten and in weekend racquetball shape. He stands there, framed by a clear, solid maple jamb. Next to him is more mill-work—a solid maple bookcase, wonderfully spare, with books and photos and his son’s trophies. There’s a picture of his boy with C. They were on the same peewee soccer team. They’re grinning, holding trophies in front of what I believe to be my leg. Marco clinks his wedding band on the bottle. I stare at him. I’ve forgotten what we were talking about. I hope he’ll pick me up.

“Want me to bring you something back?”

“No, man. Thanks, I’m good.”

I’m broke, but I can’t tell him this because while his family’s away on Long Island for the summer, I’m sleeping in his kid’s bed and he earns daily what I, at my best, earn in a month, because he has a beautiful home, because in spite of all this, I like him. I believe he’s a decent man.

“All right, man.” He goes to take a sip, then stops. He’s probably learned of my drinking problem through the neighborhood gossip channels, but he’s never confirmed any of it with me.

“Call me on the cell if you change your mind.”

He leaves. In the margins, I tally our monthly costs. “We need to make $140,000 a year,” Claire told me last week. I compute that I’ll have to teach twenty-two freshman comp sections a semester as well as pick up full-time work as a carpenter. Thomas Strawberry swims across his bowl to face me.

“I fed you,” I say to him as though he’s my dog. He floats, puckering his fish lips. Thomas, at one time, had the whole family copying his pucker face, but the boys got tired of it. The little one, my girl, kept doing it—the fish, the only animal she’d recognize. “What does the cow say?” I’d ask. “What does the cat say?” She’d stare at me, blankly, giving me the deadeye that only children can give—a glimpse of her indecipherable consciousness. “What does the fish say?” She’d pucker, the same way as when I’d ask her for a kiss—the fish face and a forehead to the cheekbone.

I packed my wife and kids into my mother-in-law’s enormous Mercedes Benz at 7:45 p.m. on Friday, June 26. It was essential for both Claire and her mother to leave Brooklyn by eight with the kids fed and washed and ready for sleep for the three-and-a-half-hour drive to Massachusetts. Claire, I suppose, had learned the trick of planning long drives around sleeping schedules from her mother. Road trips required careful planning and the exact execution of those plans. I’d have to park in the bus stop on Atlantic Avenue in front of our building then run the bags, toys, books, and snacks down the stairs, trying to beat the thieves and meter maids. Then I’d signal for Claire to bring the kids down, and we’d strap them into their seats, equipping them with juice and crackers and their special toys. Then, in her mind, she’d make one last sweep of the house, while I’d calculate the cost of purchasing whatever toiletries I knew I’d left behind.

After the last bathroom check and the last seatbelt check, we’d be off. We’d sing. We’d tell stories. We’d play I Spy. Then one kid would drop off and we’d shush the other two until Jersey or Connecticut and continue to shush until the last one dropped. There’s something about children sleeping in cars, perhaps something felt by parents, and perhaps only by the parents of multiple children—their heads tilted, their mouths open, eyes closed. The stillness and the quiet that had vanished from your life returns, but you must be quiet—respect their stillness, their silence. You must also make the most of it. It’s when you speak about important things that you don’t want them to hear: money, time, death—we’d almost whisper. We’d honor their breath, their silence, knowing that their faces would be changed each time they awoke, one nap older, that less easily lulled to sleep. Before we had children, we joked, we played music loud, we talked about a future with children. “What do you think they’ll be like?” she’d ask. But I knew I could never voice the image in my head and make it real for her—our child; my broad head, her sharp nose, blond afro, and freckles—the cacophony phenotype alone caused. I would shake my head. She’d smile and whine, “What?” playfully, as though I was flirting with or teasing her, but in actuality, I was reeling from the picture of the imagined face, the noise inside her dichotomized mind, and the ache of his broken mongrel heart.

X was already beginning to fade when Edith turned on the engine. The sun was setting over the East River. The corrugated metal warehouses, the giant dinosaur-like cranes, and the silver chassis of the car were swept with a mix of rosy light and shadow. I used to drink on a hill in a park outside of Boston with my best friend, Gavin. He’d gotten too drunk at too many high school parties and he wasn’t welcome at them anymore, so we drank by ourselves outside. We’d say nothing and watch the sun set. And when the light was gone from the sky, one of us would try to articulate whatever was troubling us that day.

“Okay, honey.” Claire was buckling up. “We’re all in.” Edith tried to smile at me and mouthed, “Bye.” She took a hand off the wheel and gave a short wave. I closed C’s door and looked in at him to wave good-bye, but he was watching the dome light slowly fade from halogen white through orange to umber—soft and warm enough through its transitions to temporarily calm the brassiness of Edith’s hair. I saw him say, “Cool” as it dulled, suspended on the ceiling, ember-like. Perhaps it reminded him of a fire he’d once seen in its dying stages, or a sunset. I watched him until it went off, and there was more light outside the car than in and he was partially obscured by my reflection.

C said something to his grandmother and his window lowered. He unbuckled himself and got up on his knees. Edith put the car in gear.

“Sit down and buckle up, hon.” C didn’t acknowledge her and stuck his hand out the window.

“Say good-bye to your dad.”

“Bye, Daddy.”

There was something about daddy versus dad. Something that made it seem as though it was the last good-bye he’d say to me as a little boy. X’s eyes were closed. My girl yawned, shook her head, searched for and then found her bottle in her lap. C was still waving. Edith rolled up all the windows. Claire turned to tell him to sit, and they pulled away.

Thomas Strawberry’s bowl looks cloudy. There’s bright green algae growing on the sides, leftover food and what I imagine to be fish poop on the bottom—charcoal-green balls that list back and forth, betraying an underwater current. Cleaning his bowl is always difficult for me because the risk of killing him seems so high. I don’t know how much trauma a little fish can handle. So I hold off cleaning until his habitat resembles something like a bayou backwater—more suitable for a catfish than for Thomas. He has bright orange markings and elaborate fins. He looks flimsy—effete. I can’t imagine him fighting anything, especially one of his own.

I tap the glass and remember aquarium visits and classroom fish tanks. There was always a sign or a person in charge warning not to touch the glass. Thomas swims over to me, and while he examines my fingertip, I sneak the net in behind him. I scoop him out of the water. He wriggles and then goes limp. He does this every time, and every time I think I’ve killed him. I let him out into his temporary lodgings. He darts out of the net, back to life, and swims around the much smaller confines of the cereal bowl. I clean his bowl in the bathroom sink and refill it with the tepid water I believe he likes. I go back to the desk. He’s stopped circling. I slowly pour him back in. I wonder if his stillness in the net is because of shock or if he’s playing possum. The latter of the two ideas suggests the possibility of a fishy consciousness. Since school begins for the boys in two weeks and I haven’t found an apartment, a job, or paid tuition, I let it go.

I wonder if I’m too damaged. Baldwin somewhere once wrote about someone who had “a wound that he would never recover from,” but I don’t remember where. He also wrote about a missing member that was lost but still aching. Maybe something inside of me was no longer intact. Perhaps something had been cut off or broken down—collateral damage of the diaspora. Marco seems to be intact. Perhaps he was damaged, too. Perhaps whatever he’d had was completely lost, or never there. I wonder if I’m too damaged. Thomas Strawberry puckers at me. I tap the glass. He swims away.

I had a girlfriend in high school named Sally, and one day I told her everything. How at the age of six I’d been treed by an angry mob of adults who hadn’t liked the idea of Boston busing. They threw rocks up at me, yelling, “Nigger go home!” And how the policeman who rescued me called me “Sammy.” How I’d been sodomized in the bathroom of the Brighton Boys Club when I was seven, and how later that year, my mother, divorced and broke, began telling me that she should’ve flushed me down the toilet when she’d had the chance. I told Sally that from the day we met, I’d been writing poems about it all, for her, which I then gave to her. She held the book of words like it was a cold brick, with a glassy film, not tears, forming in front of her eyes. I fear, perhaps, that I’m too damaged. In the margins of the yellow pad I write down titles for the story—unholy trinities: Drunk, Black, and Stupid. Black, Broke, and Stupid. Drunk, Black, and Blue. The last seems the best—the most melodic, the least concrete. Whether or not it was a mystery remained to be seen.

The phone rings. It’s Claire.

“Happy almost birthday.”

“Thanks.”

It’s been three weeks since I’ve seen my family. Three weeks of over-the-phone progress reports. We’ve used up all the platitudes we know. Neither of us can stand it.

“Are you coming?”

“Yeah.”

“How?”

It’s a setup. She knows I can’t afford the fare.

“Do you have something lined up for tomorrow?”

“Yeah,” I answer. As of now it’s a lie, but it’s nine. I have till Labor Day to come up with several thousand dollars for a new apartment and long overdue bills, plus an extra fifty for the bus. It’s unlikely, but not unreasonable.

“Did you get the security check from Marta?” she asks, excited for a moment that someone owes us money.

“No.”

“Fuck.” She breathes. Claire’s never been convincing when she curses. She sighs purposefully into the receiver. “Do you have a plan?”

“I’ll make a plan.”

“Will you let me know?”

“I’ll let you know.”

“I dropped my mother at the airport this morning.”

“It’s her house. I like your mother.” It’s a lie, but I’ve never, in the twelve years we’ve been together, shown any evidence of my contempt.

“I think C wants a Ronaldo shirt.” She stops. “Not the club team. He wants a Brazil one.” Silence again. “Is that possible?”

“I’ll try.” More silence. “How’s your nose?”

“It’s fine.” She sighs. She waits. I can tell she’s crunching numbers in her head. She turns her voice up to sound excited. “We’d all love to see you,” then turns it back down—soft, caring, to pad the directive. “Make a plan.”

2

The last time I saw them was late July at Edith’s. The boys and I were in the kitchen. X was naked and broad-jumping tiles, trying to clear at least three at once. C had stopped stirring his potion, put down his makeshift magic wand and was pumping up a soccer ball. I was sipping coffee, watching them. We were listening to the Beatles. C was mouthing the words, X was singing aloud while in the air. As he jumped, he alternated between the lyrics and dinosaur names: Thump. “Dilophosaurus.” Jump. “She’s got a ticket to ride …” Thump. “Parasaurolophus.” His muscles flexed and elongated—too much mass and too well defined for a boy, even a man-boy, especially one with such a tiny, lispy voice. He vaulted up onto the round table. It rocked. I braced it. He stood up and flashed a toothy smile.

“Sorry, Daddy.”

X looks exactly like me. Not me at three years old, me as a man. He has a man’s body and a man’s head, square jawed, no fat or softness. He has everything except the stubble, scars, and age lines. X looks exactly like me except he’s white. He has bright blue-gray eyes that at times fade to green. They’re the only part of him that at times looks young, wild, and unfocused, looking at you but spinning everywhere. In the summer he’s blond and bronze—colored. He looks like a tan elf on steroids. It would seem fitting to tie a sword to his waist and strap a shield on his back.

X could pass. It was too soon to tell about his sister, but it was obvious that C could not. I sometimes see the arcs of each boy’s life based solely on the reactions from strangers, friends, and family—the reaction to their colors. They’ve already assigned my boys qualities: C is quiet and moody. X is eccentric. X, who from the age of two has believed he is a carnivorous dinosaur, who leaps, claws, and bites, who speaks to no one outside his immediate family, who regards interlopers with a cool, reptilian smirk, is charming. His blue eyes somehow signify a grace and virtue and respect that needn’t be earned—privilege—something that his brother will never possess, even if he puts down the paintbrush, the soccer ball, and smiles at people in the same impish way. But they are my boys. They both call me Daddy in the same soft way; C with his husky snarl, X with his baby lisp. What will it take to make them not brothers?

X was poised on the table as though he was waiting in ambush. C had finished pumping and was testing the ball against one of the four-by-four wooden mullions for the picture window that looked out on the back lawn. Claire came in, holding the girl, and turned the music down.

“Honey, get down, please.” X remained poised, unlistening, as though acknowledging that his mother would ruin his chance of making a successful kill.

“He’s a raptor,” said his brother without looking up.

“Get down.” She didn’t wait. She put down the girl, who shrieked in protest, grabbed X, who squawked like a bird, and put him down on the floor. He bolted as soon as his feet touched the ground and disappeared around the corner, growling as he ran.

“They’ll be here soon,” said Claire. “Can everyone be ready?”

“Who’ll be here?” mumbled C. His rasp made him sound like a junior bluesman.

“The Whites.” His shot missed the post and smacked into the glass. Claire inhaled sharply.

“Put that ball outside.”

C looked at me. I pointed to the door. He ran out.

“No,” Claire called after him. “Just the ball.” The girl screeched and pulled on her mother’s legs, begging to be picked up. Claire obliged, then looked to me.

“‘Look what the new world hath wrought,’” I said.

She looked at the table, the ring from my coffee cup, the slop in the bowl C had been mixing, and the gooey, discarded wand.

I shrugged my shoulders. “To fight evil?”

“Just go get him and get dressed. I’ll deal with the other two.”

I put my cup down and stood up at attention. “The Whites are coming. The Whites are coming!” When we moved out of Boston to the near suburbs, my cousins had helped. I’d ridden in the back of their pickup with Frankie, who had just gotten out of Concord Correctional. We’d sat on a couch speeding through the new town, following the trail of white flight with Frankie shouting, “The niggers are coming! The niggers are coming!”

I snapped off a salute. My girl, happy to be in her mother’s arms, giggled. I blew her a kiss. She reciprocated. I saluted again. The Whites were some long-lost Brahmin family friends of Edith’s. As a girl Claire had been paired with the daughter. They were of Boston and Newport but had gone west some time ago. They were coming to stay for the week. I was to go back to Brooklyn the next day and continue my search for a place to work and live. “The Whites are coming.” Claire wasn’t amused. She rolled her eyes like a teenager, flipped me the bird, and headed for the bedroom.

I went outside. It was cool for July and gray, no good for the beach. We’d be stuck entertaining them in the house all day. C was under the branches of a ring of cedars. He was working on step-overs, foxing imaginary defenders in his homemade Ronaldo shirt. We’d made it the summer before—yellow dye, stenciled, green indelible marker. I’d done the letters, he’d done the number nine. It was a bit off center and tilted because we’d aligned the form a bit a-whack. It hadn’t been a problem at first because the shirt had been so baggy that you couldn’t detect the error, but he’d grown so much over the year, and filled it out, that it looked somewhat ridiculous.

He passed the ball to me. I trapped it and looked up. He was standing about ten yards away, arms spread, palms turned up, and mouth agape.

“Hello.”

“The Whites are coming.”

“So.”

“So you need to change.”

“Why?”

“Because your mother said so.”

“I haven’t even gotten to do anything.”

“What is it that you need to do?”

He scrunched up his face, making his big eyes slits. Then he raised one eyebrow, signaling that it was a stupid question. And with a voice like mine but two octaves higher said, “Pass the ball.” Slowly, as though he was speaking to a child. “Pass the ball.” As if he were flipping some lesson back at me. “Pass the ball.” Then he smiled, crooked and wide mouthed like his mother. He softened his voice—“Pass, Dad.”

Almost everyone—friends, family, strangers—has at some time tried to place the origins of my children’s body parts—this person’s nose, that one’s legs. C is a split between Claire and me, so in a sense, he looks like no one—a compromise between the two lines. He has light brown skin, which in the summer turns copper. He has long wavy hair, which is a blend. Hers is laser straight. I have curls. C’s hair is red-brown, which makes one realize that Claire and I have the same color hair. “Look what the new world hath wrought.” A boy who looks like neither mommy nor daddy but has a face all his own. No schema or box for him to fit in.

“Dad, pass.” I led him with the ball toward the trees, which served as goalposts. He struck it, one time, “Goooaaaal!” He ran in a slight arc away from the trees with his right index finger in the air as his hero would’ve. “Goal! Ronaldo! Gooooaaal!” He blew a kiss to the imaginary crowd.

Claire knocked on the window. I turned. She was holding the naked girl in one arm. The other arm was extended, just as C’s had been. X came sprinting into the kitchen and leapt at her, legs and arms extended, toes and fingers spread like raptor claws. He crashed into his mother’s hip and wrapped his limbs around her waist all at once. She stumbled from the impact, then regained her balance. She peeled him off her waist and barked something at him. He stood looking up at her, his eyes melting down at the corners, his lip quivering, ready to cry. She bent down to his level, kissed him on his forehead, and said something that made him smile. He roared, spun, and bounded off. Her shoulders sagged. She turned back to me, shot a thumb over her shoulder, and mouthed, “Get ready!” She sat on the floor and laid the girl down on her back.

C was still celebrating his goal—or perhaps a new one I’d missed. He was on his knees, appealing to the gray July morning sky.

“Yo!” I yelled to him, breaking his trance. “Inside.”

“In a minute.”

“Cecil, now!” He snapped his head around and stood up like a little soldier. C had been named Cecil, but when he was four, he asked us to call him C. He, in some ways, had always been an easy child. As a toddler you could trust him to be alone in a room. We could give him markers and paper, and he would take care of himself. He was difficult, though, in that he’s always been such a private boy who so rarely asks for anything that we’ve always given him what he wants. “I want you to call me C.” Cecil had been Claire’s father’s and grandfather’s name, but she swallowed her disappointment and coughed out an okay. I’d shrugged my shoulders. It had been a given that our first child would be named after them.

I thought, when he was born, that his eyes would be closed. I didn’t know if he’d be sleeping or screaming, but that his eyes would be closed. They weren’t. They were big, almond shaped, and copper—almost like mine. He stared at me. I gave him a knuckle and he gummed it—still staring. He saw everything about me: the chicken pox scar on my forehead, the keloid scar beside it, the absent-minded boozy cigarette burn my father had given me on my stomach. Insults and epithets that had been thrown like bricks out of car windows or spat like poison darts from junior high locker rows. Words and threats, which at the time they’d been uttered, hadn’t seemed to cause me any injury because they’d not been strong enough or because they’d simply missed. But holding him, the long skinny boy with the shock of dark hair and the dusky newborn skin, I realized that I had been hit by all of them and that they still hurt. My boy was silent, but I shushed him anyway—long and soft—and I promised him that I would never let them do to him what had been done to me. He would be safe with me.

Claire was still on the floor wrestling the girl into a diaper. She turned just in time to see X leave his feet. His forehead smashed into her nose, flattening it, sending her down. C shot past me and ran into the house, past the accident scene and around the corner. The girl sat up and X, unsure of what it was that he’d done, smiled nervously. He looked down at his mother, who was lying motionless on the floor, staring blankly at the ceiling. Then her eyes closed. Then the blood came. It ran from her nostrils as though something inside her head had suddenly burst. Claire has a very long mouth and what she calls a bird lip. The top and bottom come together in the middle in a point, slightly off center—crooked—creating a deep valley between her mouth and her long, Anglican nose. So the blood flowed down her cheeks, over and into her ears, into her hair, down the sides of her neck, and onto the white granite floor.

C came running back in with the first aid kit and a washcloth. He opened it, got out the rubbing alcohol, and soaked the washcloth. He stood above his mother, looking at her stained face, the stained floor, contemplating where to begin. He knelt beside her and started wiping her cheeks. The smell of the alcohol brought her back, and she pushed his hand from her face. C backed away. She raised her arm into the air and began waving, as though she was offering up her surrender.

I came inside. I took the kit from C, dampened a gauze pad with saline, and began to clean her up. She still hadn’t said anything, but she began weeping. Our children stood around us in silence.

“It’s going to be okay,” I told them. “It looks a lot worse than it is.” X began to cry. C tried to hug him, but he wriggled loose and started backing out of the kitchen.

“It’s okay, buddy.” He stopped crying, wanting to believe me. “It’s not your fault.” I activated the chemical ice pack and gently placed it on her nose.

“Don’t leave me,” she whispered. Her lips barely moved. I wondered, if it hadn’t yet lapsed, if our insurance covered reconstructive surgery. Her chest started heaving.

“Hey, guys. Take your sister in the back and put on a video.” They wouldn’t budge. “C,” I pointed in the direction of the TV room. “Go on.” Claire was about to burst. “Go.”

They left and Claire let out a low, wounded moan, stopped, took a quick breath and moaned again. Then she let out a high whine that was the same pitch as the noise from something electrical somewhere in the house. My wife is white, I thought, as though I hadn’t considered it before. Her blood contrasted against the granite as it did on her face. I married a white woman. She stopped her whine, looked at me, and tried to manage a smile.

“Look what the new world hath wrought.”

Her face went blank; then she stared at me as though she hadn’t heard what I said, or hadn’t believed what I said. I should’ve said something soothing to make her nose stop throbbing or to halt the darkening purple rings that were forming under her eyes. I shifted the ice pack. Her nose was already twice its normal size. She closed her eyes. I slid my arms under her neck and knees and lifted.

“No.”

“No what?”

“Leave me.”

“I’m going to put you to bed.”

“Leave me.”

“I’m not going to leave you.”

Although she’d been through three cesarean sections, Claire can’t take much pain. She was still crying, but only tears and the occasional snuffle. Her nose was clogged with blood. She wasn’t going to be able to get up. Claire has always been athletic. She has muscular legs and injury-free joints. It seemed ridiculous that I should need to carry her—my brown arm wrapped around her white legs—I knew there was a lynch mob forming somewhere. I laid her down on the bed. She turned on her side away from me. There was little light in the room. The air was as cool and gray inside as it was out. I left her alone.

C was waiting for me outside the door. He was shirtless, trying to ready himself to face the Whites.

“Dad, is Mom gonna be okay?”

“She’ll be fine.” He didn’t believe me. He tried another tack.

“Is it broken?”

“Yeah.”

“Is that bad?”

“She’ll be fine.” I patted his head and left my hand there. C has never been an openly affectionate boy, but he does like to be touched. I’d forgotten that until he rolled his eyes up and, against his wishes, smiled. I steered him by his head into the bathroom and began to prepare for a shower and shave.

“Have I ever broken my nose?” he asked, fiddling with the shaving cream.

“No.”

“Have you ever broken your nose?”

“Yes.”

He put the can down, stroked the imaginary whiskers on his chin, and looked at my face. I have a thick beard—red and brown and blond and gray. It makes no sense. The rest of my body is hairless. I could see him trying to connect the hair, the scars, the nose.

“Did you cry?”

“No.”

“Really?”

“Really.”

“Did you break your nose more than once?”

“Yeah.”

“And you never cried?”

“Never.”

“What happened?” I had taken off my shirt and shorts, and he was scanning what he could see of my body, an athlete’s body, not like the bodies of other men my age he’d seen on the beach. He looked at my underwear, perhaps wondering why I’d stopped at them.

He grinned. “You’re naked.”

“No, I’m not,” I said sternly.

He tried mimicking my tone. “Yes, you are.”

“What are these?” I gestured to my boxers.

“The emperor has no clothes,” he sang.

“I’m not the emperor.”

C stopped grinning, sensing he shouldn’t take it any further.

“What happened?”

“When?”

“When you broke your nose.”

“What do you mean?”

“How did you break your nose all those times?”

“Sports and stuff.”

“What stuff?”

“Sports.”

He squinted at me and curled his lips in. He fingered the shaving cream can again. His face went blank, as it always seemed to when he questioned and got no answer. I hid things from him. I always had. Perhaps I was a coward. C already seemed to know what was going to happen to him. Just as I had been watching him, he’d been watching me, making the calculations, extrapolating, charting the map of the territory that lay between us—little brown boy to big brown man.

He was already sick of it. He was sick of his extended family. He was sick of his private-school mates. He seemed world weary before the age of seven. His little friends had already made it clear to him that he was brown like poop or brown like dirt and that his father was ugly because he was brown. He was only four the first time he’d heard it and he kept silent as long as he could, but his mother had found him alone weeping. He’d begged us not to say anything to his teachers or the other children’s parents—they were his friends, he’d said. Claire wanted blood spilt. There were meetings and protests and petitions and apologies. People had gotten angry at the kids who’d ganged up on the little brown boy. One mother had dragged her wailing son to me, demanding that he apologize, and seemed perplexed when I noogied his head and told him it was okay. Other parents were even more perplexed when I refused to sign the petitions that would broaden the curriculum. Claire had been surprised.

“Why don’t you want to sign?”

“What good would it do?”

“What do you mean?”

“No institutional legislation can change the hearts of bigots and chickenshits.”

Bigots and chickenshits, my boy was surrounded by them, and no one would come clean and say it, not even me. They would all betray him at some point, some because they actually were the sons and daughters of bigots and would become so themselves, some because they would never stand by his side—unswervable. Which little chickenshit would stand up for him when they chanted, “Brown like poop, brown like dirt”? They would all be afraid to be his friend. Even at this age they knew what it was to go down with him—my little brown boy.

The Whites were coming. I had to be ready.

“Get ready,” I said. I sent my little brown boy out and took a shower.

As soon as I finished, C knocked on the door. It was as if he’d been waiting right outside.

“Yeah?”

“Can I come in?”

“No.”

“Why?”

“Wait.”

Noah had appeared naked before his son Ham, and Ham’s line was cursed forever. I didn’t want to start that mess again. I dressed quickly. I opened the door. My three children stood there: the brown boy, the white boy, and the girl of indeterminate race. They wore the confused look of children who’d just finished watching TV.

“She’s got a poop,” C said, pointing at his sister’s bottom, holding his nose.

“Yeah, poop,” said X.

“No poopoo,” said the girl. I scooped her up and smelled, then I peeked into her diaper.

“No poop.”

I got them dressed and presentable and lined up near the front door. I could hear Claire in the bathroom, fiddling with her mother’s makeup. She seldom wore anything besides lipstick. We heard the car pull onto the gravel driveway. C leaned toward the kitchen.

“Let’s go.”

“Wait until you’ve said hello.” Claire emerged from the bathroom. It looked as though the kids had shoved a golf ball up her nose and then set upon her sinus area with dark magic markers. Her children looked at her in horror, as though their mother had been replaced by some well-mannered pug.

C pulled on my arm. “Please.” He sounded desperate. He was looking at the door as though something evil was about to enter. The screen door whined and the knob turned and he bolted to the back. Edith walked in, saw her daughter, and gasped. She remembered she had company with her and turned to welcome them in.

The Whites were here: the grandmother, the daughter, the grandchildren, and the son-in-law. Edith held him by the wrist, squeezing it as though to reassure him. I don’t think Edith had ever touched me, other than by mistake—both reaching for the marmalade jar, both pulling back. Edith is still very beautiful. I think she’s a natural blonde. She has blue eyes, not lasers like X’s, but firm, giving strength to her diminutive self. Her skin is beach worn, permanently tanned from walks in the wind and sand. High cheekboned, long nosed, as if she was trying to assume the face of some long dead Peqout or Wampanoag. Massachusetts. I thought about the word, like a name, Massasoit, as though I was he, welcoming a visiting tribe from the south, the Narragansett.

The prelude to the introduction was taking too long. I offered my hand to my alleged peer. I’m six-three and have the hands of someone a foot taller. They are hard and marked by the miscues of a decade and a half of absentminded carpentry. His hand disappeared in mine, but he didn’t flinch. He did his best to meet me.

“Good to see you.” He let go, stepped back. The two women had joined Edith, staring at Claire’s nose.

“Hello,” said Claire to the elder, trying to break the spell. They stopped staring, but they couldn’t move. Claire hugged both of them, kissing the sides of their faces as well.

“It’s been so long,” she said to the younger. Claire is truly beautiful—in visage, in tone, in manner. She’s always had the ability, at least in the world she’s from, to make everything seem all right, to make people feel that things are in their proper place and all is well. It wasn’t working. As she held the younger’s hand, the elder surveyed the wreckage of miscegenation: the battered Brahmin jewel, the afro blonde in her arms, the brown man. What was there to say other than hello and good-bye? The elder looked from Edith to Claire to the girl to me. Her eyes darted faster and faster. For a moment I wanted to explain, begin the narrative simply because I believed I could and I knew she couldn’t: Milton Brown of Georgia raped the slave girl Minette. That boy-child escaped and was taken in by the Cherokee peoples on their forced march to Oklahoma.

Claire knelt to address the children—two boys, perhaps three and five. They were both hiding behind their mother’s legs. The younger bent down and pushed her sons in front of her. They couldn’t look at Claire. They buried their faces into their mother’s skirt.

“And who is this?” asked the younger, looking at X. “Oh, my goodness—those eyes!” She gasped, forgetting herself, forgetting her children. It was as if X really was reptilian and she’d fallen under his hypnotic spell. The White children, against their better judgment, turned as well. They looked as though they’d been bled, particularly next to X, who seemed ready to jump, howl, or sprint. He stared back at them, not with the fear and wonder with which they regarded him, but in an equally inappropriate way, as though he was a boy looking at cupcakes, or a carnivore looking at flesh—child-eyed, man-jawed. If there was to be a battle, it was obvious who would be left when everything shook down. The new world regarded the old world. The old world clung to its mother’s legs.

The younger tried to snap out of it. “You’re such a big boy.”

“I’m not a boy,” said X in his lisp-growl. “I’m a Tyrannosaurus rex.”

“Oh my,” she said, summoning courage for her and her brood. The other Whites tittered nervously. The elder joined in.

“You must be Michael.”

X kept staring at the children as though they were tasty meat bits.

“I’m not Michael! I’m X!”

The younger pressed on.

“These are my boys, James and George.” The smaller of the two leaned his head forward and smiled.

“Hi.”

The Whites and Edith smiled, and then cooed in unison, “Oh.”

Edith leaned into X. “Michael, can you say hello?”

“I’m not Michael. I’m X.”

“Hello,” said the older child.

The bastard half-breed son of Milton and Minette was a schizophrenic. He married a Cherokee woman and they had two children. He disappeared, and she and her children were considered outcasts on the reservation. One day she left with them and headed east.

“I’m brown,” said X.

“No, you’re not,” said the older child. “You’re white.”

“I’m brown!” he growled. “I’m the tyrant lizard king!” He snorted at them. The boys took a step back. X widened his nostrils and sniffed at them in an exaggerated way. He opened his eyes wide so that they were almost circles and smiled, coolly, making sure to show his teeth. He leaned forward and sniffed again.

She met the traveling preacher-salesman Gabriel Lloyd, settled in central Virginia, and had one child with him. Then she and Lloyd died.

“I eat you.”

As she tells it, once an acquaintance of Claire’s who knew nothing of me had asked her upon seeing C for the first time, “How did you get such a brown baby?” Claire had shot back, “Brown man.” I went outside to find C. Like his younger brother, he can smell fear. It makes X attack. The same fear causes C to withdraw—to keep his distance. He was standing in the middle of the yard with his back to the window and his ball under one arm.

“Yo, C-dawg.” He turned and saw me, smiled weakly, walked over and took me by the hand. We turned toward the kitchen. The adults had entered and Edith and Claire were handing out drinks. My boy, big-eyed, vulnerable, brown, looked in at the white people. They looked out at him. The White boys ran into the room. The older one was crying. His father scooped him up and shushed him. The younger hid behind his mother. X came in, arms bent, mouth open. He was stomping instead of sprinting. He roared at everyone and stomped out.

“Do you have to go?”

“Yeah.”

He let go of my hand.

“He’s definitely a T. rex now.” C turned and punted the ball across the yard into a patch of hostas. He watched it for a while as though he expected the plants to protest. He turned back to me, squinting his eyes, I thought, to keep from crying.

3

In the midst of the ocean

there grows a green tree

and I will be true

to the girl who loves me

for I’ll eat when I’m hungry

and drink when I’m dry

and if nobody kills me

I’ll live ’til I die.

Claire’s grandfather wanted to sing that song at our wedding, but he’d stopped taking his Thorazine the week leading up to it and “flipped his gizzard.” So he’d sat quietly next to his nurse, cane between his legs, freshly dosed, staring into the void above the wedding party.

My father tried to assume the role of patriarch. In the clearing, between the woods and the sea, under the big tent, he’d stepped up on the bandstand. Hopped up on draft beer and with ill-fitting dentures, he’d taken the microphone. “May you and your love be evah-gween.” He’d been unable to roll the r’s. The drink and the teeth had undermined his once perfect diction. He raised his glass to tepid cheers.

Ray Charles is singing “America the Beautiful.” It’s a bad idea to put on music while trying to make a plan. It may be that I need to stop listening altogether. Dylan makes me feel alienated and old; hip-hop, militant. Otis Redding is too gritty and makes me think about dying young. Robert Johnson makes me feel like catching the next thing smoking and Satan. Marley makes me feel like Jesus. I thought for some reason that listening to Ray in the background would be good, or at least better than the others. He’s not. I’m confused. I never know what he’s singing about in his prelude. It makes no sense. A blind, black, R & B junkie gone country, singing an also-ran anthem—dragging it back through the tunnel of his experience, coloring it with his growl, his rough falsetto. The gospel organ pulse, the backing voices, not from Nashville, not from Harlem, Mississippi, or Chicago—they float somewhere in the mix, evoking pearly gates and elevators going to the mall’s upper mezzanine, “America, America …” It falls apart. I remember back in my school when people used to co-opt philosophy. They’d say that they were going to deconstruct something. I thought, one can’t do that; one can only watch it happen. Only in America could someone try to make the musings of a whacked-out Frenchman utile. Anyway, the song falls apart. Perhaps even that’s incorrect; I hear it for its many parts. It’s not like a bad song, which disappears. In this, the multiplicity sings. “America …” Democracy’s din made dulcet via the scratchy bark of a native son. “God shed his grace on thee …” Things fall apart, coalesce, then fall apart again. Like at the beach—fish schools, light rays. It’s like being a drunk teen again, waiting for Gavin in the freight yard under the turnpike. The whistle blows. I see him appear from behind a car, bottle held aloft in the sunset. Things fall apart, come together, and sometimes I feel fortunate to bear witness. The timpanis boom. “Amen …” I have to hear that song again.

I don’t. I turn it off. I go into the kiddie bedroom, turn the light off, and lie down in the kiddie bed. I need to make a plan, which means I need to make a list of the things I need to do. I need to get our security deposit back from our old landlady. I need to call the English Departments I’m still welcome in to see if there are any classes to be had. I need to call more contractors and foremen I know to see if there’s any construction work. I need to call the boys’ school to see if I can pay their tuition in installments. I need an installment. I try to make a complete list of things in my head. It doesn’t work. I open my eyes and try to picture it in the darkness. Claire has always been good at making lists—to do lists, grocery lists, gift lists, wish lists, packing lists. They have dashes and arrows to coordinate disparate tasks and do the work of synthesis—laundry to pasta, pasta to rent check, rent check to a flower or animal doodle in the margin, depicting perhaps the world that exists beyond the documented tasks or between them: of fish minds and baby talk and sibling-to-sibling, child-to-parent metalanguage or microcode; the green tree that grows in the middle of the ocean; the space in which the song exists.

From downstairs Marco’s clock chimes out the half hour. Outside, around the corner, the busted church bell sounds its metal gag. I’ll be thirty-five at midnight. The phone rings. It’s Gavin.

“Mush, what’s up?” His speaking voice, accent, and tone are always in flux. It’s never contingent on whom he’s speaking to, but on what it is that he’s saying. Now he uses a thick Boston accent. Not the bizarre Kennedy-speak that movie stars believe is real outside that family. Rs don’t exist and only the o and u vowel sounds are extended: Loser becomes loo-sah. It’s a speak that sounds like it needs a six-pack or two to make it flow, to make it sing. He sounds happy, full of coffee, still inside, yet to be struck by the day.

“S’up?”

“Nothin’, mush.”

“All right.”

“Happy birthday, mush. I’m a couple of days late.”

“You’re a couple of hours early.”

“Sorry.” He switches to another speaking voice, closer perhaps, to what his must be—a smoker’s voice, in which you can hear both Harvard and Cavan County, Ireland. Gavin spent much of his adolescence with his father in jazz bars and can sound like the combination of a stoned horn player and a Jesuit priest.

“It’s all right.” I’ve been told that my accent’s too neutral for me to be from Boston.

“You don’t sound so good, man.”

I almost tell him why—more out of resentment than camaraderie. He owes me at least four hundred dollars: a credit card payment, or a couple of weeks of groceries.

“I’m fine.”

“What’s the matter, white man gettin’ you down?”

“You’re the white man.”

“No, baby, I’m the Black Irish.”

“No. I’m the Black Irish.”

“Whatever, man. You drinking?”

“No.”

I had three friends in high school: Shaky—née Donovan—Brian, and Gavin. Brian had to become a Buddhist monk to sober up, went missing for a decade in the Burmese jungle, disrobed, became a stockbroker, and died in the Twin Towers attack. Shaky, who in high school and college had been named Shake because of basketball prowess, had moved with Gavin and me to the East Village, where he had a schizophrenic break. He was now roaming the streets of Lower Manhattan and south Brooklyn. Privately, between Gavin and myself, his name had evolved to Shaky. Gavin fluctuated between poems, paintings, and biannual death-defying benders, losing apartments, jobs, and potential girlfriends along the way.

When I moved out of the place I shared with him and in with Claire, he’d come to visit and use her mugs for his tobacco spit. We’d drink pots of coffee and cackle about institutions and heebie-jeebies and never ever succeeding. Gavin never dated much. Never settled down. He rarely had a telephone and was reachable only when he wanted to be. “He checked out,” Claire once said in such a way as if to be asking me if I’d done the same. She liked him, perhaps even loved him, but she was scared of him and he felt this. By the time C was a toddler she’d unconsciously pushed Gavin out of our lives—to the point where I didn’t even think about him in her presence. But after a while, when Claire could see that I’d had enough of the gentrifying neighborhood and private-school mixers, she tracked him down and invited him to a party at our place. He’d had a good five years clean and had managed to start over again in Boston and get himself a Harvard degree. “He’s too smart and cute to be single,” she’d said, looking at a commencement photo. When he returned to New York, she’d thought it would be a good idea for us to escort him back into the mainstream.

It was this past spring and he looked well—tall, dark haired, blue eyed, strangely russet skinned, as though some of his many freckles had leaked; the Black Irish. He’d made the transition, despite a good decade of delirium tremens and shelters, from handsome boy to handsome man. His lined face and graying hair made him look rugged and weary, but his freckles and eyes still flashed innocent. He’d just had a poem rejected by some literary rag, but on arriving, he seemed fine. We sat around the table. My girl was in my lap playing with my food. There were three other couples besides us, a single writer friend of Claire’s, and Gavin. The woman, his alleged date, asked him what kind of poems he wrote.

“Sonnets.”

“Sonnets?”

“Petrarchan sonnets.”

She giggled. “How quaint.”

“Quaint, hmm.”

He emptied his water glass, refilled it with wine, and swallowed it in one gulp. Claire looked at me, concerned. He drank another glass, excused himself, and stood to leave. I caught him in the hallway.

“Where are you going with this?” I asked.

“Down, I suppose.”

Three days later he showed up, beat up and already detoxing. Claire used to try to swap stories with us, about drunken uncles and acquaintances that had hit it too hard. She’s never seen me drunk. I never had a fall as an adult. I never suffered Gavin’s blood pressure spikes, seizures, or bat-winged dive bombers—only some lost years, insomnia, and psychosomatic heart failure. But she watched Gavin convulse on her couch while her babies played in the next room. She realized that the stories we told had actually happened to us and not to someone we used to know. The damage was real and lasting. And more stories were just an ignorant dinner comment away.

“How are you, Gav?” I ask. It sounds empty.

“I’m all right, I guess. My bell’s still a’ringing a bit.” He pauses for me to ask where he’s calling from, how the last jag went down, but I don’t. He covers for me. “You bustin’ out for the weekend, or are you staying around?”

“I’m supposed to go.”

“So you’re going to be away Friday?”

“I suppose.”

“Kids making you a cake?”

“Yeah. Probably.”

“Hey, man?”

“Yeah.”

“Your kids start giving you Old Spice yet?”

“No.”

“What’s going to happen?”

“C’s going to count to thirty-five, and even though he knows the answer, will then ask me how old I’ll be when he’s thirty-five.”

He snorts a laugh. “Children—a paradox.” He shifts to Mid-Atlantic speak, the accent of one who hailed from an island between high-born Boston and London. “I have no wife. I have no children.”

“Yes.”

“I’m calling from a pay phone in a detox.”

“Yes.”

“I went on a twelve-week drunk because a girl didn’t like my poems.”

I should say something to him—that I’ll come visit with a carton of cigarettes, or pick him up, like I always used to—but Claire’s list opens up in my head like a computer file and I stay silent.

“Mush.” He switches back. “Do something. Get your head out of your ass. Go get a coffee.” More silence. “Happy birthday.”

I go downstairs. It’s dark. Out of respect for my host I leave the lights off. I go into the kitchen. It’s posh and industrial, clad in stainless steel, maple, and absolute black granite. I open the oversized refrigerator. There’s a Diet Coke and a doggie bag. Butter. Marco is a good bachelor. The house seems far too big for the three of them. I close the door and wonder if it’s better to have an empty large refrigerator or a full one. There’s a white ceramic bowl on the center island full of change. I pick through it, taking the nickels and dimes, leaving the quarters, as though big-change larceny would be too great a crime.

There’s a big window in the back of the house. It’s double height. It rises up through a void in the ceiling above. The mullions are aluminum, glazed with large panes of tempered glass. The curtain-wall spans the width of the building with one centered glass door. It’s a structure unto itself. Like everything else in the house, it’s unadorned. It looks out on the backyard, which isn’t much, gravel, an unused sandbox, two soccer goals, and the neighbors’ tall cedar fences on all three sides. There’s no ocean, river, woods, or great lawn to look upon—functionless modernism. It may well have been a mirror—two stories tall, twenty-five feet wide—the giant mirror of Brooklyn. People could come from far and wee to look at themselves in it. I could run the whole thing for you, Marco. I’ll only take 20 percent. It’ll pay off whatever it cost you to put it in within the first year. I realize I don’t know how much it cost, how much the whole house cost to buy and renovate and furnish. I don’t have any way to price the glass, the metal, the labor, the markup. Marco had asked me my opinion on the quality of the work overall, the natural maple doorjambs and stairs and cabinetry—not with any bravado—he just wanted to know if he’d been treated fairly. I never told him anything. Perhaps he’s still waiting, though it did seem strange, the master negotiator, asking me for reassurance. What could I say to him now? I’ve stolen his change and watched his building fall.

I take the money and go out. I have a twenty in my pocket, too, but I don’t want to break it—not on coffee. Breaking it begins its slow decline to nothing.

I’ve forgotten that people go out, even on weeknights. Smith Street, which used to be made up of bodegas and check-cashing stores, looks more like SoHo. It’s lined with bars and bar hoppers, restaurants and diners. Many of them are the same age I was when I got sober. There was a time when people spoke Farsi and Spanish on the streets and in the shops, but now there’s white people mostly, all speaking English, tipsy and emboldened with magazine-like style. They peer into the windows of the closed knickknack emporiums that have replaced the religious artifact stores and social clubs.