Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Sandstone Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

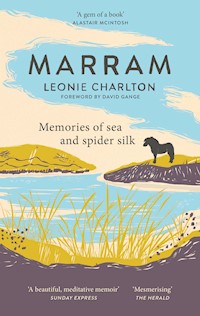

'Beautiful, meditative memoir.' -Sunday Express From the southern tip of Barra to the ancient stone circle of Callanish, Leonie and her friend Shuna ride off the beaten track on their beloved Highland ponies, Ross and Chief. In deeply poetic prose, she not only describes the beauties of the Hebridean landscape, its spare, penetrating light and its people, but also confronts the ghost of her mother and their fractured relationship.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 381

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Leonie Charltonlives in Glen Lonan, Argyll. She writes poetry, fiction and creative non-fiction and is a graduate of the MLitt in Creative Writing at University of Stirling. Her work is informed by a deep attachment to the West Coast of Scotland where she spends most of her time. She enjoys walking and time with horses as ways to feel her way into landscape, to explore whatever reveals itself through quiet attentive travel. She also loves to sleep on the hill, to experience, over and over again, the privilege of re-entering that world when she wakes.

www.leoniecharlton.co.uk

First published in Great Britain in 2020

Sandstone Press Ltd

Suite 1, Willow House

Stoneyfield Business Park

Inverness

IV2 7PA

Scotland

www.sandstonepress.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or

transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

Copyright © Leonie Charlton

Editor: Robert Davidson

Contains Ordnance Survey Data.

© Crown copyright and database right 2019

The moral right of Leonie Charlton to be recognised as the

author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

The publisher acknowledges support from Creative Scotland

towards publication of this volume.

Sandstone Press is committed to a sustainable future. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council ® certified paper.

ISBN: 978-1-913207-10-6

ISBNe: 978-1-913207-11-3

Cover design by Two Associates

For my mother, Kathryn Ade,

for her inimitable joie de vivre.

Acknowledgements

So many people supported me on this journey through the Outer Isles. Too many to mention here, but I extend my heartfelt thanks to them all, to those who helped us during our travels with their warmth and hospitality and advice, to those who so generously shared their stories. Lasting gratitude to my three companions on the trip: Shuna Shaw, her wise, good-humoured and treasured company – we have travelled many paths together and I look forward to many more; the Highland ponies, Ross and Chief, who have taught me, and brought me, so much – their hearts are vast, their level of presence endlessly inspiring. Thanks also to writer and activist Alastair McIntosh whose book Poacher’s Pilgrimage broadened my vision and enriched my experience.

Deepest thanks to my husband Martin without whom this journey wouldn’t have been possible, his generosity and unstinting support constantly amaze me – thank you from the furthest reaches of my heart. Thanks also to our three children, Brèagha, Finn and Oran, who put up with my absences, both while away, and then at home when I don’t answer questions, burn the dinner, am utterly lost to my internal worlds; their patience means the world to me.

On my writing journey I would like to thank in particular the Creative Writing Department at University of Stirling, to the tutors Liam Bell, Meaghan Delahunt, Chris Powici and Kathleen Jamie, who opened up new worlds of words to me, ones founded on integrity and possibility. Sophy Dale for her support during the writing of the first draft ofMarram, I honestly don’t know if it would ever have happened without her help with time management and her generous encouragement. Frances Ainslie for her writerly sisterhood and eagle-sharp editing eye. ToIsland Reviewwho published an extract from an earlier version of this book. Finally, thanks to Robert Davidson and the whole Sandstone Press team.

Author's Note

I inherited a love of wildlife and landscape from my parents. My feeling of interconnectedness with the natural world defines and sustains my existence. Throughout this book I have taken the poetic licence of capitalising plant and animal names; not on every occasion, but in the moments that call for particular emphasis on a plant or animal’s presence. It feels crucial, in these times of climate crisis and mass species extinction, that we bring our full awareness and appreciation to the diversity around us. I have been inspired by writers such as Glennie Kindred who capitalises all tree names in her bookWalking with Trees, and Robin Wall Kimmerer, who inBraiding Sweetgrassbreaks with grammatical convention to write freely of Maple and Heron.

Leonie Charlton

Taynuilt, Argyll

2020

Contents

Acknowledgements

Author's Note

Preface

Day One: Oban to Barra

Day Two: Tangasdale Machair to Eoligarry

Day Three: Exploring Eoligarry

Day Four: Barra to South Uist

Day Five: Garrynamonie to Bowmore

Day Six: Howmore to Iochdar

Day Seven: Staying in Iochdar

Day Eight: Iochdar to Balivanich, Benbecula

Day Nine: Benbecula to Grimsay

Day Ten: Grimsay to North Uist

Day Eleven: Carinish to Vallay

Day Twelve: Leaving Vallay

Day Thirteen: Solas to Berneray

Day Fourteen: Berneray to Harris

Day Fifteen: Getting Organised

Day Sixteen: Leverburgh to Horgabost

Day Seventeen: Horgabost to Aird Asaig

Day Eighteen: Aird Asaig to Kinloch Rèasort

Day Nineteen: Kinloch Rèasort

Day Twenty: Loch Rèasort to Aird Asaig

Day Twenty-one: Aird Asaig to Callanish

Preface

I’m sitting in my writing box in Glen Lonan, Argyll. It’s early September, and three months since I got back from riding through the Outer Hebrides with my friend Shuna and our two Highland ponies, Ross and Chief. I can see Ross now, grazing on grass that has lost its summer sheen. The forested hillside rises up behind him, a single Rowan in full bright-berry stands out amongst the Birch and Oak. Beyond the soft shrug of these trees, half hidden in cloud, is Ben Cruachan. The writing box is the back of a refrigerated van that my father converted. He took out the steel meat hooks, put in windows and a door. Despite his attention to detail it relies on a dehumidifier to stay dry. Today is my first time in here for a while and I’m aware of its particular smell; a combination of damp emulsion and plywood, metal and mould. I push the window open wide and breathe in the cuspy autumn air.

Bracken has grown up past the windowsill. Coppery tones seep upwards from the ground and colour the under-fronds. There are Thistles too – purple flowers long gone but the heads are still holding onto tufts of down, silver turned to peaks of grey after weeks of rain. A single Foxglove folds across, its leaves riddled with rust-edged holes, empty flower cups darkening to a loam brown. On the inside of the windowsill is a stem of Marram Grass I found in my saddlebags after the trip. It is sharp and lucent. It reminds me of how I’d felt coming home, bright and still after all those slow-spent hours in the marram and cotton grass.

My mother passed to me a passion for horses which has been a lifeline, a source of love and grounding throughout my life. My relationship with her was fraught with pain and misunderstanding, at times I’d wondered if life would be better without her. Then she died and I was broken. Almost seven years after her death, long enough for nearly every cell in my body to have renewed itself, it felt like the grief and regret were intensifying. I was bone-weary of the guilt,a redundant emotionMum herself had always said. She’d been a jeweller and a passionate collector of beads. During the months of planning for the Hebrides trip an idea had formed to leave a trail of beads for Mum. Where better than through this archipelago that she’d loved, itself a necklace of granite and sand, schist and gneiss, strung on streams of salt and fresh water.

I have loved the Hebrides for decades, ever since travelling to some of the islands on work-trips with my father, Max Bonniwell, who was a vet in Oban. One summer Dad took my younger brother and me on a camping trip through the Outer Hebrides, memories of that fortnight remain amongst the most luminous of my life. I associated the islands with him and everything he embodied, which was the opposite of the emotional, cultural and physical chaos of life with Mum. Dad represented safety and stability. He smelt of veterinary disinfectant. He knew the names of all the seabirds and of all the sailing boats. Mum had also travelled widely in the Hebrides, but I’d never been out there with her, and now, in this unexpected way, was my chance.

The islands and strands we crossed, the people and wildlife we met, the days of travel alongside the ponies, the memories that surfaced as I laid down beads, would all wrest changes in my inner landscape. At the head of Loch Rèasort, where Harris meets Lewis, I would nearly lose my pony. I would be stripped back by fear in that place and find my own bedrock that had been hidden under layers of life-silt. The journey would prove to be a pilgrimage of love and personal sea-change.Marramis the story of how I found new relationships with my mother and with myself. It is also a love story of place, not just of how environment renews and nourishes us human beings, but also of how our wakefulness, our attentiveness, may give something back in return. We leave behind footprints steeped in appreciation, and perhaps the best gift of all to the sand and peat, two sets of smooth hoof prints.

Today seems a fitting day to start writing about this journey. The apples are half turned to red on the trees outside. A young Buzzard is mewing, he has been doing it for weeks while he flies elliptical circles. Each day the calls are getting stronger and higher. He is on his own now.

Day 1 to Day 14: Castlebay to Leverburgh

Day 15 to Day 22: Leverburgh to Callanish

DAY ONE

Oban to Barra

Our stuff was spread out across the metal-rimmed table in the dining area of MV Isle of Lewis: water bottles, camera cases, lip salve, cable ties, bananas, a stack of pink OS maps numbered 31, 22, 18, 14 and 8. There were two books placed face down at significant pages: Pocket Walking Guide No 3, Western Isles; The Outer Hebrides, 40 Coast and Country Walks. A purse full of Mum’s beads was there too.

We moved everything to one side when the smiling steward brought across our plates of fish and chips and rolling peas. ‘So, here’s to our trip then,’ said Shuna, her eyes aquamarine in the sunlight coming through the salt-chalked glass. We clinked the tops of our Peroni beer bottles. Shuna and I had been friends for fifteen years and we’d done several long horse trips together. We were both aware there were big gaps in our planning this time, but there wasn’t much we could do now, just hope that everything would work out. I told her about the man talking on the radio that week of the benefits of travelling without plans, how it leaves you open to new experiences, to meeting people in a different way. I’d taken it as a positive sign.

We drank quickly and, sitting there, watching diving Gannets spill the sea into spindrifts of white, our shoulders began to soften. The water bottles rolled backwards and forwards across the table as the sea pushed the boat up beneath us. I picked up the bead purse. It wasn’t exactly classy, made of soft plastic, the words ‘LAS VEGAS’ repeated in gold and silver and white across a shiny black background. Mum definitely wouldn’t have approved, but it was the perfect size and had a good sturdy zip. I opened it and looked inside at the huddle of beads, wondering where they would all end up. There was also a little roll of ivory silk thread which I’d found in Mum’s bead drawers. I’d originally thought I’d take a fishing line to tie the beads onto things because it was tough and wouldn’t weather. Then I’d started to worry that a bird might get caught in it, or worse. The silk thread would decompose eventually, but there was no need for the beads to stay put forever; Mum’s necklace would be fluid, made up of gestures of emotion in a certain place, in a certain moment. It would change shape, the beads free to move through storms and tides and seasons.

The boat rolled again and I felt my guts tilt. I tried to close the zip but a loose strand of silk had snagged in the zipper. I carefully teased it out, my fingers touching this spool of thread that Mum must have handled countless times. I thought of her hands and felt that old familiar wash of pain. I could see her fingers now, red from the cold. They were always cold. We were all always cold, living in those old stone-walled houses and barely able to afford to keep one room warm. She used to say that her hands were ugly, that they were manly. She didn’t wear rings because she hadn’t wanted to draw attention to her hands. I remember watching them for hours while she worked, her dexterity, her skill, even after the first brain tumour when they trembled and trembled. Yet still she’d persevere with threading the tiniest crystals, the tiniest seed pearls, taking as long as it took. Handling things she loved in those hands she didn’t love. Holding treasures between her fingertips, angling them to the light.

My brothers, Will and Tom, and I always said that she should have been rich; she had a taste for expensive things, for luxury, and yet had so little of that in her life. I knew she wouldn’t have approved of all the beads I’d chosen. I’d been in a hurry that day. Had found it difficult opening those drawers that still smelt of her. I’d kept thinking about her nails, always filed smooth so they wouldn’t snag on the thread. Then in her last few years how they had been bright red. How she’d had acrylic nails ‘done’ by a professional every month. Standout nails. So, did that mean she’d made peace with her hands by then? I hadn’t asked, that would have felt dangerously like connection. I was sorry that we hadn’t got a professional in to do her nails when she was in the Lynne of Lorne Nursing Home, that we’d let somebody we never met do them, a volunteer. Yes, her hands. They haunted me. Even when she was dying, and the rest of her rattled tiny, her hands had stayed big. Right to the end. I looked at my own hands as I pulled the zip closed. I didn’t know whose hands I had, but I knew they weren’t my mother’s.

It was bright out on deck. The bolted-down plastic seats were coral red under the overhead sun. The ferry’s jade-streaked wake trailed back down the Sound of Mull towards the mainland. I could make out the double peak of Ben Cruachan, my home hill. We’d already passed the Lighthouse on Eileen Musdile on the starboard side, and the green contours of Lismore, that fertile limestone island where my pony Ross was born in the year 2000. Now on the port side was the Isle of Mull where Shuna’s pony, Chief, was born in 2010. The ferry trip was taking us past their birthplaces. It hadn’t occurred to me until then that the ponies, now in an Ifor Williams horsebox on the vehicle deck below us, were both islanders.

I stood on the stern deck for a long time. The engine’s vibrations travelled up through my feet to the tangle of nerves under my ribcage. The air smelt of salt and diesel. As we came to the end of the Sound of Mull, Ardnamurchan Lighthouse snuck into sight on the point. To the west the isles of Rum, Eigg and Muck hunkered down on the horizon. Rum’s hills lifted in easy blue across the miles of sea. Ross is a Rum Highland pony with rare ancient bloodlines. These ponies were bred to be versatile, one of their jobs being to take deer carcasses off the hill. They were described by Dr Samuel Johnson in his 1775Journey to the Western Islandsas ‘very small but of a breed eminent for beauty’. They have unique colour combinations: fox dun and silver dun, liver and mouse and biscuit dun too. Some have zebra stripes up their pasterns and eel stripes along their spines. Ross’s passport states his colour as ‘dappled chocolate’; his mane has blonde highlights and in summer you can see the dark dapples across his body. It may be myth, but some say the unusual colours come from stallions that swam ashore from Spanish Armada shipwrecks and bred with native ponies. I love to think of the Spanish horses mixing with the Scottish horses on this Atlantic seaboard. I also love to think of some of those shipwrecked horses having survived, and Ross carrying their blood all these centuries later. Chief is a bright silvery grey. They are a striking pair, but most important of all they are great travel companions. Ross’s experience makes up for Chief’s inexperience, and Chief’s bravery bolsters Ross in moments of doubt.

We’d left the Sound of Mull behind and were now out in the Sea of Hebrides. The last time I’d made this crossing was ten years previously, in July 2007, with Martin and the children on our way back from a holiday on Barra. It had been a hot windless day and the crossing was smooth. We’d leaned over the railings as we sailed through a broth of Basking Sharks. The sea was alive with them, their black fins visible a long way into the distance, cutting through the glittering sea. Today there was no sign of them, but every now and again a great spear-billed Gannet glided past, quickening my pulse every time.

I found Shuna standing in the observation lounge. It was exhilarating up there, all that height and light and the views through 180° of glass. My feet stepped across the carpeted floor. There was a quiet reverence in the air with people dotted about, binoculars on tables, maps out, knees crossed.

‘It’s fascinating,’ Shuna whispered, turning to me. ‘The couples, I think they must be the Jaguar Club, and they’re all in matching pairs. Look, over there, those two, angular and skinny, and this couple, bespectacled and round-faced, and these two,’ her voice dropped even lower as she nodded towards the nearest couple, sitting with their long legs stretched out, ‘they’ve both got hair that sticks out at the back, and matching socks.’ We were both smiling. A woman walking past swayed suddenly as she lost her balance. ‘Better than Alton Towers, this is,’ she laughed, her face wide with delight. I recognised her from the ferry queue. She was in a camper van which had stood out; the rest of the queue was mostly made up of classic Jaguars, crouching convertibles with their soft-tops down, their curved panels gleaming suede green and pearl.

Will the owner of the pickup and horsebox please go to the front desk.The voice on the tannoy sounded serious.

‘Shit, hope they’re okay,’ I said loudly. Faces turned to look at us as we made our unsteady way back down the steep stairs.

‘It’s nothing to worry about,’ the steward said, ‘just thought you might like to check on the ponies, seeing as it’s such a long trip. It’s going to get a bit rougher for the next couple of hours.’

‘They’re so nice on this boat,’ Shuna said as we made our way down another two steep flights of stairs to the vehicle deck.

‘Look at that.’ I reached out and touched her arm. From where we stood we could see into the trailer. Chief had his head over in Ross’s side of the box. They were both resting, cheek to cheek, ears touching.

I opened the side door and two sets of dark eyes looked down at us. It was warm in the box and the windows were steamed up, we breathed in the earth-sweet smell of horse and haylage. It struck us both then, that we were really doing this, we were on the boat out to Barra, the four of us. My eyes were swimming as I closed the drop-latches.

Back at our table in the dining area I scanned the sea. I’d never seen so many Dolphins, lines and lines of them coming towards us in leaps of slate-dark joy. ‘A calf!’ I looked to where Shuna was pointing, her face showing pure delight. The calf was in a line of about ten adults, bounding towards us broadside to the boat. She was her mother’s half-size shadow, matching her fin for fin, eye for eye. Then they were almost beneath us and their underbellies glowed pale amber in the sunshine as they dived, backs shining in perfect arcing alignment.

My heart raced. There we were, high above the plimsoll line, Ross and Chief below us in their tilting trailer, and these Dolphins swimming through the sea beneath them. I thought about horses that had travelled on other boats in past centuries, and remembered why horses in the Americas were so extraordinary. Because only the fittest had survived the gruelling sea voyage from Spain, suspended in slings, living on rancid water and weevil-infested feed. The trust of horses constantly astonishes me. They would have followed their handlers along gangplanks, down into a swaying dark hold where they would have sickened and often died. The survivors would have stepped out onto new land, probably emaciated, but alive and prepared to face whatever their handlers asked of them.

Resting my chin on my hands, I remained without moving for a long time as the boat started to roll more steeply. Shuna, wisely, had already lain down on the dining area floor. Now I didn’t dare move. It was that critical stage where the slightest change can tip the balance of seasickness from uncomfortable to sick-bag stage. I’m a coward with nausea. My parents separated when I was two, and travel sickness was connected to high emotion from then onwards. I can still recall the nauseous feeling of being at the airport in Accra. I would have been three when Mum and my brothers and I left my father in Ghana where he worked at a veterinary aid project. Then there were long car trips with Dad when he was back on leave, and the sailing trips with him. I never did find my sea legs. When Dad came back from Africa for good there were car trips to the halfway meeting point between Argyll and Dumfries and Galloway, usually the car park outside the Little Chef at Dumbarton. I’d inherited travel sickness from Mum, who understood how being touched was the last thing you wanted when you were being sick. North of Dumbarton Dad would put his hand on my back when he stopped for me to be sick in this lay-by or that lay-by. I never asked him to take his hand away though.

I heard a commotion of seabirds and opened my eyes. The surface of the sea was pixelated with silver Sprats and above was a stramash of feeding seabirds. Dad would know what those birds were. If he was here, he’d be out on the deck, binoculars up, watching intently. How many years had it been since I stood on a CalMac deck, or sat on a wet bench in his Drascombe Lugger, listening to him naming birds: ‘Kittiwake, fulmar, storm petrel.’ Hearing how his voice would lighten, understanding that birds made him happy, and knowing how happy that made me. I promised myself to make more of an effort to see him when I got back from this trip. Looking down at the shadows of the lifeboats in the surf below, I closed my eyes and squeezed my hands together, as if closing them around time itself, stopping the slippage. Surf bulged against the side of the ferry as nausea reeled through me.

Oban was five and a half hours and ninety odd miles behind us. Shuna and I were back out on deck with the islands of Muldonaich and Vatersay on the portside and Barra on the starboard. As the ferry turned smoothly into Castlebay, three Arctic Terns serrated the air with their cries as they swooped to the sea, trailing their forked tails behind them. These three ‘sea swallows’ had just made it back from their wintering grounds in the Antarctic, ten thousand miles, nowthatwasa journey.

Kisimul Castle, on its rock in the bay, was lit up in sunshine. The hill behind it, Heaval, was black in cloud shadow. Not even the marble statue of the Madonna and child was visible today, but the Church of Our Lady of the Sea made up for it, resplendent in sunlight in the village below. I can’t see Roman Catholic icons and churches without thinking of Mum. She had burst out of a convent when she was eighteen and made up for a crushing and abusive education every second of the rest of her life. I’d set out on this trip with a purse full of beads and a belief that what I needed to do was make my peace with her, but I would come to realise that I’d already done that when she was dying from the brain tumour that slowly took everything away from her. Only the quick-fire in her eyes stayed until the very end. She had died on a night with a full moon that shone hard and bright as platinum, which was somehow fitting for a woman who was full-hearted and flinty-sharp in equal measure. Yes, I had made my peace with her in those terrible winter-thin months. It was myself I needed to make peace with now. The regrets around our relationship were still grabbing at the back of my throat, still making it hard for me to breathe sometimes.

Scanning the darkened hillside for the white lady, I could hear Mum talking with passion about the Roman Catholic Church, the cruelty of the nuns, the hypocrisy of the priests. What else would you expect from a religion that believes animals don’t have souls, she’d say bitterly. I had taken this to heart and always felt uncomfortable around the rituals: the robes, mass, confession. I’d heard too many stories of what went on behind closed doors, the cruelty suffered by Mum in the convents she’d gone to, and by her two brothers in their boarding schools with the ‘brothers’. Yet, at the very end, she’d chosen to have a rosary on her bedside table. My mother, so full of contradictions, always surprising. I hope it brought her comfort but, for me, I carry a prejudice. I shiver at religious iconography. My chest tightens when I see a nun’s habit, a priest’s collar. I am an animist through and through. That is where I find my God, in the natural world. In the birds and animals and frosts and mosses, and in the humanity of our own animal being.

Would owners of all vehicles please make their way to the vehicle deck.

On the way down we stopped to take a photograph of a pinned notice:THE PEOPLE OF BARRA WELCOME ALL VISTORS. HOWEVER, THE FOLLOWING RULES WILL APPLY:Rule number four read: THE SPEED LIMIT IS 60mph NOT 30mph. Beneath our shared amusement we were both anxious, and worried about traffic. Chief was very inexperienced and, although Ross was fairly confident, I had my own issues around traffic. To be honest, I found riding on the roads terrifying. People had been warning us that this year the island roads were busier than ever, even this early in the season.

As we drove up the hill I looked in the side mirror. The last vehicle to disembark was a red quad bike, the same colour as the funnels on the ferry towering above it, a raw brave red. In front of it was one of the classic Jaguars, azure and flawless as the sky overhead. That picture. Right there. Utter perfection. I turned to face forwards again and let out a ‘whoop’ as we drove past the signFailte. Live it. Visit Hebrides.

‘You must be Shuna,’ said the woman standing at the driver’s window. ‘How was the crossing? How are the ponies?’ She rattled off questions. Naomi had pulled over in front of us when we’d stopped to get our bearings. ‘I’ve been keeping an eye out for you. Not too many horseboxes come off this ferry.’ She was laughing and her ponytail whipped round in the wind. Naomi, a friend of a friend of a friend, had pre-arranged for us to camp on the common grazing at Tangasdale Machair in the south-west corner of the island.

‘Follow me, I’ll show you where to go.’

When we took their halters off, both ponies lifted their heads and sniffed the air. Ross led Chief off to explore, swinging his head from side to side, the great pony explorer. In the evening light we agreed they looked magnificent, lit up from inside and out. We loved seeing them like this. Loose-limbed they set off, adventure and newness defined their muscles, altered the lift of their necks. We found a sheltered spot out of the wind and, after arranging to meet Naomi later, set up camp. Every now and again the ponies would come back to our camping spot, a hollow where the machair sward merged into marram grass, and grazed distractedly on the new grass that was just starting to show. Then they would canter off once more in wild mustang mode.

Once the tent was up, sleeping mats and bags in, we decided to have a look at the beach and walked with the ponies along sandy paths strewn with empty, sun-bleached snail shells. The air was a-spin with the chatter of Starlings. Ross’s mane and the marram were the same sun-on-straw colour, both being flicked seaward by the wind. On the beach the ponies’ soft footfall joined the soundscape of the Oystercatchers’ and Common Gulls’ commotion-at-dusk and, higher up, like a stitch being pulled in the evening sky, the call of Geese.

A woman and a dog approached us from the north end of the bay. ‘Hello, do you mind if he meets the ponies? He’s just a pup, he’s interested…’ She told us he was a red and white setter. Not a breed either of us knew, he was stringy and windblown and all ears and tongue-lolling delight.

‘I’ve been here nearly a week,’ said the hatted and scarfed woman, her shoulders pulled up towards her ears, ‘and I’m shattered by the wind.’ I felt the sincerity of her words. Chief, like the clouds, was limned by the dropping sun. Silver strokes flashed along his top-line, the curve of his ear, tangled in his whiskers and tail. The rest of his body was in near-darkness, his sand-shadow stretched away from the sea back towards the dunes, the machair and the hill where a single salmon-pink roof stood out against the pearly rock.

Later, in the warmth of Naomi’s house overlooking Castlebay, with mugs of strong tea in our hands, we heard a little of the life she shared with her son and husband, their multiple jobs including veterinary supplies dispenser and firefighter at the airport, and their many animals. Those animals were at the centre of their world. A Norwegian Forest Cat and Tibetan Mastiff puppy absorbed the living room in precious long-haired splendour, and over the fireplace was a picture of Naomi’s three horses, looking down at us from a rock on the hill, rulers of their world.

That night we lay listening to Oystercatchers piping outside and the wind tugging at the tent as we passed the hip flask back and forth. We had a lot to celebrate. By dawn we’d put on every item of clothing we had with us, including coats, hats and buffs. It was Baltic, the tent and sleeping bags had come short of the mark. We’d bought the spring/summer range; autumn/winter would have been more suitable. It was the first of many uncomfortable nights, yet the magic of being there together was inextinguishable. In the night the ponies galloped by the tent and I wondered if I was dreaming, but theboran-beat of their hooves on the machair and the racket of disturbed Oystercatchers were more real than even my wildest, most vivid dreams.

DAY TWO

Tangasdale Machair to Eoligarry

Packing away the tent was like trying to put a feral cat into a bag. The wind was sending the light fabric into a frenzy when I was ragged with lack of sleep. We worked quietly and quickly, spots of rain pinging our skin, that weighty grey sky was about to let rip.

‘Good job we’ve got the horsebox this morning,’ Shuna said with feeling. The rain pummelling on the metal roof syncopated with the soft hiss of the gas stove. Steam bloomed on the inside of the window while on the outside fat raindrops smeared the Marram Grass into a leaden sky. There was no sign of the ponies so we guessed they’d found a sandy hollow to shelter in and were standing side by side, heads down, bums to the rain and wind.

Shuna carefully sliced a banana into our porridge. ‘Honey?’ she asked. I nodded and sat on a plastic-wrapped haylage bale. Luxury. Most nights, camping would be without the trailer. The rough plan as we rode up the islands was to drive the pickup and trailer to the next ferry crossing, leave it there and hitch a lift back to the ponies. Or ride first, and hitch back to collect the vehicle. Either way would require some leapfrogging and a willingness to go with the flow. On other trips we’d had everything organised in advance: daily itineraries; each night’s accommodation sorted; drop offs planned; and food parcels sent ahead. This time, since we needed the trailer to get the ponies onto each ferry, we’d decided to make the most of that extra space. We had a chest full of food: tins of sardines, smoked oysters and mussels, a few camping-ready meals, bags of couscous and pasta, dark chocolate, whisky, coffee, Earl Grey teabags, Nairn’s oatcakes, hunks of cheese, packets of Naked bars, porridge oats, honey and raisins, salted peanuts and cashews. We definitely wouldn’t starve. We also had a case of Prosecco and six half-bottles of Oban whisky to give as gifts.

When Shuna handed me a cup of porridge, I noticed my resistance but was determined to be a porridge eater on this trip. Mum had loved her porridge, but she’d made hers with full-fat milk and lavished it with double cream and brown sugar. No salt and water for her. In the horsebox that morning I managed to eat almost all of my porridge before any thoughts of gagging snuck in. Perhaps the success was down to my spork. Having shopped, planned, prepared for this trip for a long time, we had all the camping gear. The tiny foldable gas stove was Shuna’s pride and joy, crouching steady on its stainless steel lobster legs on the sawdust-strewn floor. As well as being a professional horse trainer Shuna also works as a cook. Her organisation around food is fabulous. This is great for me, and for my food anxiety. The thought of running out has always sent me into a panic. I have no reason for this, I’ve never been food deprived. We may not have had treats when I was growing up, there was never any spare money, but there was always food. Mum did funny things around food though. She’d have butter that wasonly for her, the rest of us had margarine, and chocolate that wasonly for her. She had a good excuse, having been perpetually hungry in boarding school, in the convents in Wales, England and Belgium. Other children’s parents would send goody parcels. Hers hadn’t, I never asked why, but the result was that food, especially her own ‘special treats’, had been very important to her. Perhaps some of her anxiety had rubbed off on me.

The strong aroma of coffee mingled with the fresh wood shavings and yesterday’s horse dung, three smells that filled me with a deep sense of well-being. The tiny new Bialetti was perfect for slipping into a saddlebag. Lifting its lid I saw the last of the coffee bubble up. Our hearts got lively with caffeine and the rain battered on. We weren’t in any hurry, having only seven miles to ride that day and were happy to wait and see if the rain would pass. We brought our gear in from the pickup, packed our saddlebags, looked at the map and folded it into the waterproof case, had another coffee. Then the sun pressed a golden light through the clouds which, from one moment to the next, transformed the morning.

At the burn to wash the pots, I found each wet stem of marram grass was balancing light like a sword edge. A drake Mallard flew over, his head a startle of tourmaline. I cleaned the pots with strands of sheep’s wool that I found caught on the fence. Judging by the lines of dark Bladderwrack tangled along its base it got regular batterings by the sea. The fence was a work of art, patched with zigzags of baler twine holding the upper strand of barbed wire to the Rylock below. Some of the twine was orange, some was yellow, and the crisscrossing seemed perfectly symmetrical between the fence posts that leant in all angles from their volatile sandy base. I have always had a thing about gate and fence repairs and my eye picks them out everywhere I go. I like to imagine the minds behind the hands that mended. I like to see the layers of time and weathering made visible by each twist of wire, knot of string, breadth of rope. The ingenuity and creativity always delights me, but I’d never seen such decisive zigzagging as this before. The colours were synthetic and strident, but even they weren’t resistant to the weathering. Fibres that had twisted awry of the main body of twine had faded to translucence. Mum would have appreciated this fence: its withstanding, its refusal to be beaten.

I took the bead purse out of my pocket. It was wet. My Ebay-bought Gortex jacket hadn’t stood up to the drive of the rain earlier. I unzipped the purse and looked inside and the moment suddenly sat heavily on me. A memory of a morning in Oban and Islands District Hospital, turning to wave goodbye to Mum from the ward door, seeing her face brightening.

‘You said the words,’ she’d said, in a smalling voice from the bed.

‘What?’ I’d answered.

‘You saidI love you.’

I ran a hand through the water that flowed topaz-coloured down from Loch Tangasdale, and settled for two beads: a smooth oval wooden one and a second ceramic one that was irregularly shaped and glazed in a bold metallic bronze. Carefully threading them onto a length of the silk string, I twisted it onto the upper strand of wire, making sure a barb kept the two beads separate. The bronze bead rested beneath the wire next to a triangulated summit of orange baler twine. The wooden bead rested on top of the wire. I was satisfied, and wondered if the crofter would find them as he or she made their next round of repairs, or if they’d make it to the sea, or fall to the sand, before being seen by a human again.

We were looking for Chief. We’d found Ross alone by the roadside fence being petted by walkers, he was walking beside me now through the dunes. Every now and again he’d stop and lift his head and call out a high-pitched neigh, his whole body vibrating with tremors that carried along the rope to my hand, up my arm, into my body. The three of us listened for a reply but couldn’t hear anything above the wind. Shuna was quiet. It doesn’t take long for the imagination to go into overdrive: Chief’s legs caught in wire, Chief escaped and gone for miles, Chief swimming out to sea, Chief stolen. We followed sets of hoof tracks through the dunes where they’d been galloping in the night. Down on the beach the tracks thinned to just one set of hoof prints which led to the far end of the bay. There the fence line ended a little short of the sea, and if he really wanted to, a pony could cross the rocks and head up onto the hill. Shuna set off at a run. Ten minutes later we met her and Chief coming back round the shoreline.

‘He was so pleased to see me! Don’t know what he was doing round there, but he’s fine. He’s totally fine.’ Relief lightened her face.

We’d left the road and were riding down a grassy track to the burial ground on the point at Borve Point. The ponies were striding out, looking all around them, their hooves making soft thuds on the sandy soil. We passed a sheep track that trickled through the machair to a single standing stone, clearly a favoured rubbing post. There was a long fenced off potato strip, the sandy soil piled up in neat ridges, tattie shaws just starting to show. Then, between Ross’s ears, a huddle of crosses showed up on the skyline against a pewter sea. They were all facing eastwards, to us and to the rising sun. The graveyard was enclosed by a tall dry-stone dyke. It had fallen down in places and the ubiquitous strands of barbed wire were strung across the gaps, ribbons of last year’s silage bale wrap fluttered in the wind like Tibetan prayer flags. A plaited fisherman’s rope lay in recumbent coils between the dyke and the shore. It was melded into the shoreline, its hemp spirals sewn through with Moss and Silverweed. Alongside it, boulders that had rolled from the wall were embossed in yolk-yellow Lichen, cat’s-tongue rough to the touch.

We got off and led the ponies to a gate on the far side of the burial ground. A sign told us it was a Commonwealth graveyard, that casualties from both the First and Second World Wars were buried here. We took it in turns to hold the ponies while the other wandered amongst the stones, listening, touching, reading. The lettered, dated summations of lives, short-lived and long-lived, were being taken over by Lichens, some like smooth spillages of cream, others sage-green and wiry. The air was strung with the oscillating calls of Curlews, and Lapwings flung themselves in somersaults against the wind. This place of remembrance was a sanctuary for birds. I felt a sense of privilege to be there that was almost too much to bear. We walked in silence towards the tip of the point, the carved gravestones replaced by body-sized rocks left by the sea, or glaciers, or maybe both. A Curlew whistled in alarm and we stopped. The sky was full of birds watching over their nests, we had a sense of trespassing on hallowed ground. The bird calls escalated, echoing our own sense of wonder. As we retreated a slender head and neck peered at us from above a rock, there was something strangely adolescent about this bird as it wheeled up, all awkward elegance before the sky stole it. Later, the bird book told us it was a Godwit.

We walked back in the lee of the wall. Underfoot was a mixture of dried cow dung and sand, a refuge for cattle in the winter months. As we left quietly through the gate, its metal rungs holey with rust, an Arctic Tern trailed its long tail with impossible grace in the air above us.Shapeshifter,I thought, as a fine rain blew across our faces.

The Curlews’ spiralling calls had tuned me in to a world tilting ever-so-slightly differently on its axis, a world I wanted to know more deeply, and one I’d need to learn a new language to explore. Shuna had told me, down at the graveyard, that Karen Matheson, her sister-in-law, had family buried there. Karen’s mother had left Barra when she was sixteen to go and work in the hotels in Oban. She had been ashamed of her Gaelic, as many were at that time, and hadn’t spoken it in the home. In spite of this, or perhaps because of it, Karen had gone on to become a world-renowned Gaelic singer, forming the band Capercaillie with Shuna’s brother Donald Shaw, and becoming an impassioned ambassador for the language. Her last album was a return to her Hebridean roots, recording traditional songs and poems. ‘Urram’, the Gaelic for ‘respect’ and ‘honour’.Urram, what a beautiful word.

‘Look, I can post my cards.’ We were back on the tarmac road and Shuna was pointing to the postbox on the verge ahead. As she leant over and posted from the saddle, delight spreading across her face, I laughed at the improbability of it all. At us Michelin women padded out in full waterproofs, our faces red-ruddy from the wind. At the two glossy postcards sent on their way at the end of a quiet township road on Barra.

As the road cut inland the surge of beryl sea on our left was replaced by fields and stock fences. In places each barb on the wire was coated in sorrel cattle hair, like felted pearls. ‘Allasdale,’ said Shuna, looking at a road sign ahead. ‘I read what that means:elves’ milking place, from the Norse’. I imagined them nipping in and milking the cattle, their fair dues. For what, I wondered.