Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Influx Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

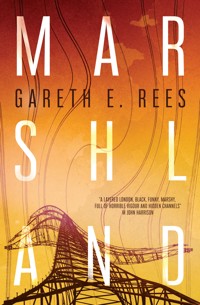

Cocker spaniel by his side, Gareth E. Rees wanders the marshes of Hackney, Leyton, and Walthamstow, avoiding his family and the pressures of life. He discovers a lost world of Victorian filter plants, ancient grazing lands, dead toy factories and tidal rivers on the edgelands of a rapidly changing city. As strange tales of bears, crocodiles, magic narrowboats, and apocalyptic tribes begin to manifest, Rees embarks on a psychedelic journey across time and into the dark heart of London itself. First published by Influx Press in 2013, Marshland is a deep map of the east London marshes where nothing it as it seems, blending local history, folklore, and weird fiction in a genre-straddling classic of contemporary place writing. This fully revised and expanded 2024 edition features brand-new material and never before-seen photographs from the author's archive.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 328

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

1

2

3

MARSHLAND

DREAMS AND NIGHTMARES ON THE EDGE OF LONDON NEW EXPANDED EDITION

Gareth E. Rees

Influx Press

London

4

5

6

DEDICATION:

In memory of Andrew Weatherall, who enjoyed this book so much that he made a Marshland mixtape.

mixcloud.com/Hackneymarshman/marshland-the-andrew-weatherall-mix/8

9

10

11

I do dimly perceive that whilst everything around me is ever changing, ever dying, there is underlying all that change a living power that is changeless, that holds all together, that creates, dissolves, and re-creates.

Mahatma Ghandi

CONTENTS

12

AUTHOR’S FOREWORD

The marshland of London’s Lower Lea Valley is the most important place in my life. Its canals, football pitches, industrial estates and meadows irrevocably changed me.

On the day I crossed the Lee Navigation to the misty wonderland between Hackney and Walthamstow, I passed through the looking glass. The citified, adult version of myself shrank into the form of an enraptured child as I crouched beneath slimy bridges to listen to thundering trains, swung my legs from a giant banquet table beneath towering pylons, and crept into leafy enclaves where Page 3 girls beamed at me from torn tabloid pages in the smoking embers of campfires.

There was the potential for amazement and terror behind every bush, for this was a place where bears and crocodiles were rumoured to lurk in the undergrowth. These wild beasts had either slipped through time or remained here since the Ice Age, feeding on unlucky travellers and drunken vagabonds. It was a place where the corpses of the drowned rose from the canal; where time-travelling Victorians returned to work in the ruined filter beds; and ghosts from demolished factories drifted through luxury apartment blocks.

As a freelance writer who worked from home, I was able to walk though this landscape every day for years with my half-blind cocker spaniel, Hendrix. The more we explored, the more fascinated I became. The Lower Lea Valley’s 14fusion of Ice Age marshland, medieval pastureland and industrial edgeland was weird in its truest sense. There were interactions between objects which shouldn’t have existed in that time or place – a pair of shop mannequin’s feet in a tree; a heron in a bomb crater framed by a glass skyscraper; office furniture on the bend in a river; the sounds of a dual carriageway reverberating in dense woodland; a horse grazing beneath an electricity pylon; a long-horned cow beneath a stalled commuter train. It could be eerie, too. I’d stumble across abandoned tents in the scrub and hear crackly Sixties hits drift across a riverbank as shadows shifted on the walls of derelict warehouses and silent narrowboats emerged from coils of fog.

Eventually, I began to catalogue my experiences in a blog, which I called The Marshman Chronicles. I wanted to capture the imaginal place as much as the physical one; the fictional aspect as much as the factual; and add my own threads of folklore to that which already circulated. Those posts caught the eye of Gary Budden and Kit Caless from Influx Press, who asked me to write a book. I had never written a book before and had no idea what I was doing. Was this an autobiographical novel? A psychogeography? A collection of weird fiction? A time travel adventure? Alternative guidebook? Influx was a new indie press with a desire to challenge the usual narratives, so they encouraged me to put it all in there. This resulted in the unusual concoction you hold in your hands. A blend of disparate elements and genres that don’t normally go together, just as the marshes themselves are an incongruous mishmash of functions and chronologies. In its review, The Londonist wrote that ‘One day, all books will be written like this’, but 15this has not been borne out in the decade that has passed since. Books that can’t fit into genres are much more difficult to sell. And so this remains a punk rock debut album of a book. Odd, dishevelled and awkward – naïve, even – but full of energy.

Marshland was the first step in a journey of discovery that resulted in all the fiction, non-fiction, music and lyrics I produced over the next ten years. My eyes had been well and truly opened. Everywhere I wandered now brimmed with narrative potential, no matter how ugly or mundane: a supermarket car park, new-build housing estate, business park, factory or hospital outbuilding. Folklore can take root in places like these. Monsters and murderers can stalk their corridors and enclaves. Ghosts can haunt their ruins. Memories of love and loss can cling to their concrete, asphalt and steel.

Every place has a story to tell if you take the time to look and listen. The world becomes strange and mysterious if you allow yourself to dwell in a space, focus your attention on the details, and open your mind to its resonances and synchronicities. Even familiar objects can become weirdly unfamiliar the more closely they are observed; warping, shifting and receding from comprehension. Sometimes, it’s as if the inanimate becomes sentient. Seemingly unconnected objects and events start to link together into a narrative that you only vaguely understand but which compels you to speculate further. For a writer, that’s when the magic happens. But also, sometimes, the horror. When you probe beyond the veil of material appearances there are demons to be found among the angels. Nightmares among the dreams. You dabble at your peril. 16

My experiences in the marshes mangled my sense of time and space, dismantling my old ways of viewing the world and my place in it. It sparked creative obsessions that consumed my attention at the expense of my working life and marriage. You can see the first cracks forming in this book, and if you were to read the two books that followed it – The Stone Tide and Car Park Life – you’d bear witness to the complete disintegration.

Among its hallucinatory timeslip tales and oddball hyperlocal histories, Marshland describes the daily walks I took between 2008 and 2013, capturing the place in all its seasons, wind, rain and shine. In a sense, it has become a historical artefact, depicting East London in the white heat of gentrification as the 2012 Olympics approached and debate raged over the value of green spaces and the expansion of privatised space. As protestors lay down in front of truck wheels on Leyton Marsh to prevent basketball courts being built on an irreplaceable wildflower meadow, members of the Occupy London movement were camped outside St Paul’s Cathedral and taking over disused buildings throughout the city, calling for a change to an unjust global economic system that was ‘causing massive loss of natural species and environments’ and ‘accelerating humanity towards irreversible climate change’.

At the beginning of this narrative, I was a thirty-five-year-old man only recently married with a newborn baby. Now I am fifty years old, divorced, remarried, with two scowling teenage children. Yet despite the ravages of time on my poor face, the marshes have barely changed. There is little in this book that won’t resonate with anyone who visits today. Despite it being a much busier place, with signposts 17to tell you where you are and information boards to tell you what you are looking it, you will find that almost everything described in these pages is still in its place, albeit differently graffitied and a little more degraded, with most of the shabby industrial canal side now developed into properties. The battles to protect this public space have not ended either. Local campaigners continue to resist attempts to build on the marshes, turn it into a live events hub or raise yet more apartment blocks on its peripheries.

If anything, Marshland might be more relevant in this era of mass extinction and ecological breakdown. We cannot continue to expand into every available space, destroying ancient meadows, woodlands and wetlands, along with their intricate ecosystems. We need to let rivers and marshes return to their natural ebb and flow so they might act as barriers to floods as storms rage and seas rise, rather than damming waterways for our short-term convenience and building housing estates on floodplains. Above all, the people living in this hectic, exhausting and deeply troubled modern world need a free space to breathe, wander and dream. This is what the marshes can still offer anyone who dares step over the threshold.

Gareth E. Rees, 2024.

18

I

ENTROPY JUNCTION

My first daughter, Isis, was born in Homerton Hospital in November 2008. My parents looked after our cocker spaniel, Hendrix, while we adjusted to our new life. Our ground-floor flat became a cocoon. We warmed bottles and washed muslin cloths. We worked through boxes of congratulatory chocolates. We welcomed visitors and stacked teddy bears in the corner.

We did the parent thing.

When Hendrix returned, I realised, with queasy vertigo, that we were a proper family. The sort you see in children’s drawings standing next to a house beneath a smiling sun. So it was on a bright, freezing December afternoon that my wife, Emily, and I took Isis out for the first time. We went to Millfields Park on the borderland of the marshland. Daddy, Mummy, baby, dog.

The enormous pram seemed ridiculous as we wheeled it into Millfields. Isis was ensconced in layers of white. All you could see was a pixie nose and her eyes, freshly woken from myopia, taking in the elms passing overhead. I took some photos, feeling like a tourist who had just quantum-leaped into someone else’s life. 20

As we walked down through the park towards the River Lea and the marshes of East London which lay beyond, the city’s gravity began to lose its hold and my happy narrative fell to pieces. From the water’s edge a shape moved towards us at speed. Though small in the distance, I could tell it was a bullmastiff or some similar barrel-chested Hackney man-dog. I knew right away it was heading for us. It didn’t waver from its route, thundering on the frozen ground, growing closer and larger.

Emily and I stopped walking and watched it hurtle up the slope. Hendrix sniffed the grass, oblivious. I removed his lead from my pocket and called him, but it was too late. The dog was upon us. It ground to a halt before Hendrix and the two began to spin. The mastiff’s tail, stiff and vertical, quivered with aggression. Hendrix’s tail was slung low as he snarled back. A voice echoed across the park as a dreadlocked man staggered towards us with a lead.

I reached out to grab Hendrix’s collar. It was like pushing the ‘ON’ button on a blender. The two dogs whirled into a blurry frenzy round my arm, barking, teeth bared. I staggered back in pain, bitten. Emily cried out, jerking the pram away. The animals were separated but circling again.

‘Sorry man,’ wheezed the owner in a Caribbean accent, shaking his head. ‘He’s a puppy. You okay?’

He had a hold of his dog, but it was too late. The idyll was shattered. My family dream exposed for what it was: an artificial construct, fragile as glass. Isis screaming her tiny lungs out. Emily shaking her head in disappointment, me staggering around saying, ‘shitshitshit’. A scenario which would characterise many subsequent family occasions. 21

A few months later, I saw them again in Millfields, this time on the Lee towpath. I spotted the dog first. He ran up to Hendrix,chest puffed out, whorls of hot air snorting from his nostrils. Then I recognised the owner. The dreadlocks, the deep vertical lines on his face. He wore a dark blue tracksuit and smoked what was either a rollup cigarette or the last remnant of a joint.

The dogs circled. Mr Mastiff’s dog rose up on his hind legs and gave Hendrix a couple of right hooks. Hendrix took two steps backwards and plunged into the river. All that remained on the water’s surface was a cloud of dirt. His head bobbed up and he started paddling against the current. He moved absolutely nowhere at first, then backwards as he lost strength.

‘Sorry, sorry, sorry,’ Mr Mastiff mumbled.

I dropped to my belly and tried to reach into the water. The ledge was too high to get my hands on him.

‘My legs,’ I said to Mr Mastiff. ‘You’ll need to hold my legs.’

I piled my mobile phone, keys and loose change on the concrete, lay on my stomach and said, ‘Okay – now.’ Mr Mastiff held my ankles and slid me forwards until I was dangling over the water, clawing at Hendrix’s collar.

If I’d been someone else passing by – if, say, I’d been myself on one of my walks – I would have returned home and written excitedly about seeing a Caribbean man in a tracksuit doing ‘the wheelbarrow’ with a scruffy white bloke on the edge of the river while a tiny dog swam backwards. But I wasn’t the observer. I’d become one of those people you see doing inexplicable things when you come to the marshes. I’d been exploring the place only a matter of months and already I had been assimilated into the weirdness. For this 22reason, I consider that moment – being dragged back over the ledge with Hendrix, soaking wet – as a kind of baptism.

From that day forth, I named this place ‘Entropy Junction’. It was the frontier crossing on the borderland between city and marshland, where the competing gravities of two worlds created a zone of chaos and disorder.

Things happened here.

It was Hendrix, a cataract-stricken puppy, jet black and bumbling, who first brought me to this frontier, shortly after my wife Emily and I moved from Dalston in the west of Hackney, to Clapton in the north-east of the borough. When he was strong enough to walk the distance, Hendrix led me away from Hackney’s Victorian terraces through Millfields Park. I remember the day well, the perfume of freshly cut grass and Hendrix’s tiny legs tripping over twigs. We passed a Jack Russell shitting pellets into a shrub. A jogger whooped, ‘Yeah!’ and boxed the air. Toddlers shrieked on the swings. A drunk lay on a bench, beer can on his belly oozing dregs. A suited man mumbled into a mobile phone. Two kids kicked a football. A murder of crows amassed by a bin. Then, at the bottom of the park, it all came to a halt.

At the River Lea, the park ended abruptly at a tumbledown verge, twisted with weeds and dandelions, iron bollards tilted like old tombstones, chain links snapped. Where you’d expect a towpath to be was, well, nothing. A soup of stone and soil poured into the water. Across the river a concrete peninsula bristled with weeds, empty but for an office chair, traffic cone and a Portaloo circled by gulls. 23A moorhen stared back at me from a rusted container barge. Beyond the corrugated fencing, geese flapped across a wide sky where pylons, not tower blocks, ruled the horizon. Near a footbridge, narrowboats were moored beneath a brow of wild scrub. Ruddy-cheeked people in Barbour jackets and mud-spattered wellies strolled across the river, followed by giant dogs, as if a time-space portal had opened between London and some faraway countryside.

This was my first encounter with the marshland. It was a place unmarked on my personal map of the city. Until now I’d perceived London as a dense, functional infrastructure spreading out to the M25. Each citizen’s experience depended on the transport connectivity between their workplace, home, and favoured zones of entertainment. Londoners journeyed through their own holloways, routes worn deep into their psyche. The idea of deviating from this psychological map hadn’t occurred to me. I assumed I lived in a totalitarian city. London’s green spaces were prescribed by municipal entities, landscaped by committees, furnished with bollards and swings. There was no wilderness. There was no escape. You couldn’t simply decide to wander off-plan. Or so I thought.

Now my dog had brought me to a threshold between the city I knew and a strange semi-rural wetland known as ‘the marshes’. On one side of the river, London was in hyper flux, perpetually regenerating, plots as small as toilets snapped up by developers, gardens sold off, Victorian schools turned into apartments, bomb sites into playgrounds, docklands into micro-cities, power stations into art galleries. Everything was up for grabs. On the other side of the river – a stone’s throw away – lay a 24landscape of ancient grazing meadows scarred with Second World War trenches, deep with Blitz rubble, ringed by waterlogged ditches, grazed by long-horned cows, where herons and kestrels hunted among railways, aqueducts and abandoned Victorian filter beds. It was untamed, unchanged in some parts since the Ice Age. It had not yet been claimed by developers. It was nobody’s manor.

Discovering this place was like opening my back door to find a volcanic crater in the garden, blasting my face with lava heat, tipping reality topsy-turvy.

In that year when Hendrix dropped off the edge of London into the Lea, the riverside was the booming frontier of Hackney’s redevelopment. For decades the Lea had been dominated by Latham’s timber yard and other warehouses. Now these edifices were being torn down and the skeletons of waterfront flats rose in their place, wrapped in wooden hoardings. Among the graffiti tags, guerrilla advertising stickers and splashes of dog piss, developers’ posters envisioned the future in neat lines and diagrams. There was a phone number you could ring to discuss the price of a space in the sky that hadn’t been built yet. Above the rim of the hoardings, yellow excavating scoops bowed on hydraulic necks.

A few old warehouses remained on the towpath. Sometimes a figure stood smoking in one of their iron-grilled doorways, ghosts of fag breaks in times past. Signs on the walls said DANGER, DEEP EXCAVATION. Beyond, I could hear the chugging of the diggers and the crunch of steel on 25brick. Eventually the wall would come down and a shiny corrugated edifice would rise in its place, reflecting fresh aspects of light onto the river.

Month by month the topography of the river’s edge mutated. Gaps appeared between buildings and quickly filled with cones, planks of wood, crumpled sleeping bags and beer cans. Protective wooden hoardings were built out onto the towpath, narrowing the passage. At times I was forced onto strips of path so slender I tottered on the water’s edge to let cyclists past. London was flowing inexorably east, like hot lava, cooling on contact with the Lea, bulging at the riverside, forcing me over. I could feel the city’s desperation to burst across and swallow the marshland whole. Some mornings a layer of thick mist shrouded the river’s surface, as if the inert world on the marsh side of the water was sublimating on contact with the super-heated city.

I could see where previous layers of development had cooled, especially by The Anchor and Hope pub, a Victorian watering hole near High Hill Ferry, an old river crossing point. Among the cyclists supping cask ales, jocular men in a hotchpotch of fashions from several eras – bobble hats, donkey-jackets, tracksuits, garish shirts and teddy-boy coats – were dwarfed by a hill of 1930s multistorey flats and newer municipal school buildings. There used to be two other pubs here, The Beehive and The Robin Hood Tavern. They formed a bustling hub at the northern end of Hackney’s own Riviera, a popular East End holiday resort. Until the early twentieth century the riverside from the Lea Bridge to Springfield Park enjoyed a festival atmosphere, with crowds, boaters and stalls selling sweets, cockles and whelks. Today it’s little more than a narrow thoroughfare for cyclists and walkers. 26The towpath drops into steep, littered verges of weed, where rats scuttle and swans nest in islands of sludge.

There’s something heroic about The Anchor and Hope pub standing firm against time, its drinkers obstructing the commuter flow, while its environs have been fossilised by the pressure of progress. The Beehive was closed sometime after the Second World War, later converted into flats. The Robin Hood Tavern was demolished in 2001. The site was a waste-ground for several years until locals converted it into a community garden. Now a pub sign adorned with an image of Robin Hood and Friar Tuck overlooks a driftwood bench and herb beds. A flyer pinned to the gate advertises ‘Folk Dancing’. It’s one of many pockets of resistance along the Lea’s edge where the past refuses to vanish.

Beneath a railway arch, a smiling sun goddess and a Green Man are painted on Victorian brick. The latter is a symbol found in many ancient churches and cathedrals. Nobody is sure of its exact meaning and origin. Many pagans link the Green Man to the cycle of birth, life, death and decay. He has also been linked to Robin Hood (perhaps a reference to the Robin Hood Point crossing nearby, where the pub once stood) and other figures, including the Green Knight. Nearby, in a plot behind the rowing sheds, a scarecrow watches over the allotments. Latin graffiti daubed on the path by the narrowboat moorings reads Omnia Lumina Fiat Lux (‘Let there be light’). From a branch overhanging the river a driftwood dragon spins in the breeze. These intriguing folklore fragments suggest something wild and primal trying to break through the veneer of modern Hackney. 27

It was the school holidays. The sun was hazy warm. I was crossing the footbridge over the Lea from the marshland to Millfields with Hendrix, absorbed in my thoughts, when I neared a group of kids milling at the edge of the park. I’m accustomed to bored teenagers in parks, but there was something unsettling about this scenario. They were all male. There must have been twenty boys whispering and jostling in a huddle.

As I drew closer the fog of self-reflection lifted. I became aware something was about to happen. The boys nervously adjusted their jackets. The park crackled with tension. I wanted to turn back but I was too close now. The touchstone was lit. With a whoop, one of the boys vaulted onto his bike 28and bolted across the grass towards the Lea Bridge Road. The group swarmed after him. I was directly in their path but they flowed past me like I wasn’t there.

One boy said, ‘We’ll come at them from three ways.’ Another reached in his coat.

‘Come on!’ shouted the lead boy, peddling furiously. The pack began running at a pace. At the railings they slowed and jeered at two figures on bikes who jeered back from the Lea Bridge Road.

Two gunshots rang out. Screams filled the park. The playground emptied. Women ducked their children behind trees. Another gunshot, followed by cheers. The two boys fled on their bikes. The gang fizzed by the railings, collectively deciding what to do next. In the dead silence that followed the final shots, I realised they were probably going to run back the way they came, brandishing weapons. I was the only person wandering in the middle of the park. I picked up the pace, hoping my camp speed-walking would not be considered inflammatory. When I looked back, the gang had vanished under the Lea Bridge.

I checked the local news. There was no report of the incident. Nobody died. Nobody got shot. But later I discovered that many centuries before this shootout, Millfields Park was the scene of an Anglo-Saxon skirmish known as the Battle of Hackney. It was alleged to have taken place there in AD 527 when Octa, King of Kent, was having trouble with Erchewin, founder of Essex, who had turned against him. Octa gathered his forces in Hackney for a march on London but was surprised when Erchewin’s supporters came out to meet them there for a pitch battle. 29Perhaps what I’d witnessed that day in the park was a historical cycle repeating; another leak of dark energy from that fissure where tectonic plates of two worlds grind together in Hackney’s molten borderland.

30

II

THE MEMORY OF WATER

In a hot room in Singapore on 6 July 2005, the President of the International Olympics Committee, Jacques Rogge, announced that London had won its bid to host the 2012 Olympic Games. The British delegation leaped for joy. Meanwhile, a city came unglued. A bacchanalian horde celebrated in London’s pubs. Jubilant citizens imagined a future where pleasure-domes rose in the east; where dollars, euros and yen poured into the city’s coffers; where specimens of human perfection raced through our streets and fucked joyously for the salvation of humankind in a Stratford neo-village.

Before the hangover set in the following day, bombs tore apart three underground trains and a double-decker bus on Tavistock Square. London fell to her knees and wept. Once again, the spectre of violence tapped on her shoulder to remind her of IRA attacks, the Blitz, the Great Fire, plague pits, Viking sackings, clashing prehistoric beasts, the grinding of the Earth’s tectonic plates and the lakes of fire that bubble beneath her. This city is a pile of bricks and mortar on shifting sands. We are only flesh and bone. Nothing is safe.

Four days after the bombs, a crocodile came to the River Lea. On a peaceful morning, a delegation from the Inland 32Waterways Association travelled by boat up the tidal stretch of the Old River Lea from Stratford to Hackney Marshes. The passengers included Mark Gallant of the Lea Rivers Trust and ecologist Annie Chase. They were making an assessment of the Lower Lea Valley before work began on the Olympic site. As they sailed up the river, they started noticing weird holes in the riverbanks.

Holes aside, everything seemed as normal. Moorhens and coots paddled in the waters. A heron preened itself on the bank. A Canada goose drifted across the bow of the boat. Then, suddenly, it vanished beneath the water. In less than a second the bird was gone. All that remained were concentric ripples on the surface. The shocked crew waited in vain for the goose to reappear. Soon it dawned on them.

It was murder.

Mark Gallant later told the BBC: ‘I felt responsible for these people and I wasn’t about to go over and investigate, or get too close – put it that way.’ He added: ‘Whatever that thing was, it had to be big.’

There are many predators in England’s waterways. Pikes. Otters. Catfish. Escaped terrapins. But in this case the finger of suspicion pointed to a crocodile. Could such a beast lurk in the Lea?

Journalists from the East London and West Sussex Guardian went to find out. Lacking the essential tracking skills of modern crocodile hunters, they discovered nothing. They called on the services of Mark O’Shea, a television herpetologist. After his own investigation, he suggested that the culprit could be a discarded pet caiman or ‘a large pike’.

Gallant said: ‘I’m sceptical about the idea it could be a pike… I would’ve thought if it was a pike, there would have 33been a bit more of a struggle. The way this thing disappeared was almost instantaneous.’

This story could have died along with the Canada goose. But on 13 December 2011, the beast returned. Mike Wells was having a cup of coffee with a friend on the deck of his boat when he saw a ‘goose go vertically down – in the space of half a second it had gone’. He estimated the weight of the bird to be around seven kilos. This wasn’t something a fish could pluck from the surface like an insect. He told reporters: ‘It was pretty surprising the speed with which it disappeared – and it didn’t come back up.’

In the rising heat of Olympic fever, the story hit the mainstream press. A Daily Mail headline screamed:

KILLER BEAST STALKS OLYMPIC PARK AS EXPERTS FEAR ALLIGATOR OR PYTHON IS ON THE LOOSE

The Mail described whatever was in the Lea as a ‘mysterious giant creature’. They reminded readers, ‘The number of swans on the river and waterways near the newly-built £9bn Olympic Park is also dropping.’

They were wrong, of course. What lurks in the Lea isn’t a crocodile. What was seen in the rippled surface after the goose disappeared was a reflection of those human faces, terrified of what lies beneath the city, wild, ancient and unstoppable. The memory of water.

The Thames cuts a lonely swathe through maps of contemporary London. She’s one of the last visible remnants of a natural landscape lost beneath concrete and steel. She trails sadly through the megalopolis like a party ribbon hanging from the back of a crashed wedding limousine.

It wasn’t always this way. In the past the Thames enjoyed the company of many tributaries, including the Fleet, the Effra, the Tyburn, the Westbourne, Walbrook, Falconbrook, Stamford Brook and Counter’s Creek. These rivers have been bricked up, turned into sewers, forced underground. The forty-mile-long Lee is one of the few to stand firm against the insatiable city as it spreads east. She begins life in the Chiltern Hills at Leagrave, flows south through Ware, Cheshunt, Waltham Abbey, Enfield Lock, Tottenham, Clapton, Hackney Marsh, Hackney Wick, Stratford, Bromley-by-Bow, Canning Town and finally Leamouth, where she pours into the Thames.

In the lower Lea Valley the river carves a border between the modern boroughs of Hackney, Leyton and Waltham Forest, and the historical counties of Middlesex and Essex. Between the ninth and eleventh centuries AD, the Lea was the frontier between Saxon England and Danish Viking territory. The Danish Vikings had established a foothold in East and North England in AD 865, carrying out raids on the Saxons, looting villages and stealing livestock. To keep the peace, King Alfred signed a treaty with King Guthrum agreeing a border which stretched from the Thames up the Lea, then up the Ouse to the ancient track known as Watling Street. This border became known as the Danelaw. The Saxons would stay to the south and west of the Lea. The Danes would keep to 35their patch to the north and the east. The Vikings, however, were a notoriously restless bunch. In AD 894, the Lea was wide enough for a fleet to sail as far as Ware in Hertfordshire, their ships adorned with images of dragons, banners bearing ravens, the crew hungry for pillage. Saxon legend has it that Alfred responded by draining lower reaches of the river, cutting off the water channel at Waltham and stranding the enemy.

This was only the beginning of human meddling with the Lea. Over the centuries, artificial channels have sapped her strength. She’s been diverted through mills, forced into filter beds, hemmed into reservoirs and siphoned away by factories. In the eighteenth century the process of canalisation began. A series of cuts and locks aided the transportation of grain and building materials into the city. Like a harpooned sperm whale at the mercy of hunters, the Lea grew slower with every blow. Each new drainage channel was a slashed artery leaching her lifeblood. Her wounds filled with silt and her heart clogged with oil spewed from industrial barges. Slower she moved, her vision narrowing, until she was flanked on both sides by timber, concrete and iron. By the end of the Industrial Revolution, the Lea had been forced into the servitude of London, her curvy lines straightened, her naturally wayward character repressed and conditioned by the demands of the metropolis.

Today the river remains a repository of the city’s filth, riddled with faecal e-coli and human effluence. Water from washing machines, toilets and baths in London’s many poorly connected homes flows directly into the river. Oil leakage from millions of cars and trucks is washed into the water during heavy rain. 36

The stretch of river between the Lea Bridge weir and the bridge to the Middlesex filter beds is one of the most visibly polluted sections of the canal. The oil and shit is joined by a flow of…

beer cans cigarette packets

vodka bottles hubcaps flip-flops

naan bread surgical gloves probiotic yoghurt cartons

party balloons vomit shampoo bottles

fried chicken boxes Styrofoam containers tyres

nappies

carrier bags

fake tan canisters shopping trolleys

decomposing rats

In the summer, sewage and duckweed form black pustules on the surface, bubbling in the midday sun, the air curdling with the stench of faeces. The geese, swans, ducks, coots, moorhens, gulls and crows of the Lea aren’t put off by this pollution. They’re too addicted to the abundant supply of food alongside the parks. People throw bread into the water, scatter crumb trails on the towpaths, abandon takeaways on the grass or stuff their leftovers into tiny park bins. By morning the foxes have scattered the bounty wide. Thanks to a perpetual banquet of processed food, the wild birds are junkies, hooked on white flour, salt and chemical 37treatment agents, bonded to the towpath by their addiction. They nest among cans, bottles and bags, unheeding of the squalor. Geese stalk towpath users, begging for a scrap, eyes milky with humiliation. These are the tortured guardians of the threshold.

Occasionally, skeletal blue boats with names like Taranchewer go to work, dragging rubbish from the canal with a conveyor belt. In the six months before the 2012 Olympics, these craft worked on overdrive and the Lea was miraculously cleansed. You could see your face in it – without your face being superimposed with kebab meat and a can of Old Jamaica Ginger Beer. It didn’t last. Within a month of the closing ceremony a sofa bobbed against the weir among a mush of algae, bottles and cans.

But the Lea is irrepressible. She’s not like those other tributaries which submitted to the tide of concrete. She isn’t broken so easily. It’s at the Lea Bridge weir, where the effects of canalisation are most evident, that something remarkable happens. The Lea splits into two. One part of her flows towards Stratford in an artificial cut known as the Lee Navigation. The other plunges into Hackney Marshes, where she reconnects with a deeper chronology, before the city, before people, when monsters hunted on her banks.

She remembers herself.

The transformation is instantaneous. The water slides down the weir and foams at the bottom of the drop. Thick curls of oxygenated white spin down a green gulley where umbrellas of giant hogweed loom. Trees bow at her passing, trailing leaves in her current. Joyously she flows beneath a cast-iron pipe, twirling round rocky islets, swelling and spilling over muddy slopes. She burbles and bubbles. She breathes again. 38

Bream, chub, carp, roach, eel and flounder return to her shallows to spawn. Kingfishers and dragonflies dance on her fringe. Herons, cormorants, coots, moorhens and gulls gather on her rocks. In autumn, teal, tufted duck and gadwall fly from Siberia and Scandinavia to pay their homage. Dogs crash into her in search of sticks. Fishermen huddle around small fires on her banks and stare at her lovingly.

There are other signs of human devotion to this stretch of river. A kingfisher is spray-painted on the outflow of a flood relief channel where it joins the river, celebrating the return to natureof prodigal water. On a concrete wall nearby, a mutant bird with three eyes and ice-cream-cone-shaped beak caricatures the degenerate creatures of the canalised Lee. These animal totems have never been whitewashed by the council. They understand that the old river can look after herself. What she wants, stays. What she doesn’t want, she forcibly ejects.

39

When heavy rains come, she swells into the trees and shrugs her rubbish onto their branches. When the waters subside, she leaves behind a sarcastic parade of blue flags, polythene streamers and bottle-top confetti. The further she flows through Hackney Marsh’s woodland of poplars, oak, maple, ash and blackthorn, the more Proterozoic the Lea becomes. Her banks get wider and blacker with mud. Dead branches jut from the surface, creating eddies that catch your peripheral vision, as if something has been dragged beneath the water. Trees stagger into her, trunks warped and split. The air clags with rotten vegetation. Dock leaves the size of whale tongues flop from forests of nettles. Nature seeps from a deep fissure beneath the riverbed, threatening to subsume you and pull you down into the earth.

As the old river arcs past the site of Dick Turpin’s long-demolished watering hole, The White House, towards Temple Mills, she runs temptingly clear, sand and stone sparkling on the riverbed, geese racing over tendrils of green weed. Here the tarmac footpath ends. To continue walking on the riverside towards the Olympic Park, you must duck through a shaggy tunnel of weeping willow, strewn with motoring paraphernalia: number plates, driving licenses, car logbooks and torn MOT certificates. The path ends at a wall of bush which forces you away from the river, up an incline. At the top you stand on the edge of a crossing over the A12, confronted with a view of the Olympic stadia, flyovers and the Westfield Shopping Centre like a concrete layer cake. Here you straddle a paper-thin border between London’s future and that dark, primal memory which flows beneath the city and bubbles, occasionally, to the surface in the Old River Lea. 40

It’s no surprise that it was on this stretch of water that the boat passengers saw a goose killed by a crocodile – a terrapin – an otter – a pike. Whatever it was, it tells you everything you need to know about the Old River. She’s the city’s amygdala. She’s the wild nature threatening to burst through the cracks in our streets. She’s the insubordinate river, resisting London’s spread, refusing assimilation.

When the human project fails, when London lies in ruins, and global warming raises the seas and brings forth mighty deluges, it will be the old Lea who leads the great river rebellion. Rise! she’ll cry. Arise! From Dagenham to Hounslow, the rivers of London will burst free from their subterranean prisons, spilling crocodiles onto the streets to feast on the last survivors, engulfing the lowlands, swallowing up old marshes and turning parks into new marshes. Brooks will become streams. Streams will become rivers. Those rivers will connect with each other like reawakening synapses until they form a single aquatic consciousness. She will remember a time before her humiliation at the hands of humankind, when the waters of the world were united as one, and the land was a lonely continent.41