1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Librorium Editions

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Moscow is a city of slow historical growth, and down to the present time its different parts have wonderfully well retained the features which have been stamped upon them in the slow course of history. The Trans-Moskva River district, with its broad, sleepy streets and its monotonous gray painted, low-roofed houses, of which the entrance-gates remain securely bolted day and night, has always been the secluded abode of the merchant class, and the stronghold of the outwardly austere, formalistic, and despotic Nonconformists of the ‘Old Faith.’ The citadel, or Kreml is still the stronghold of Church and State; and the immense space in front of it, covered with thousands of shops and warehouses, has been for centuries a crowded beehive of commerce, and still remains the heart of a great internal trade which spreads over the whole surface of the vast empire. The Tverskáya and the Smiths’ Bridge have been for hundreds of years the chief centres for the fashionable shops; while the artisans’ quarters, the Pluschíkha and the Dorogomílovka, retain the very same features which characterized their uproarious populations in the times of the Moscow Tsars. Each quarter is a little world in itself; each has its own physiognomy, and lives its own separate life. Even the railways, when they made an irruption into the old capital, grouped apart in special centres on the outskirts of the old town their stores and machine-works and t

Politicsheir heavily loaded carts and engines.

However, of all parts of Moscow, none, perhaps, is more typical than that labyrinth of clean, quiet, winding streets and lanes which lies at the back of the Kreml, between two great radial streets, the Arbát and the Prechístenka, and is still called the Old Equerries’ Quarter—the Stáraya Konyúshennaya.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

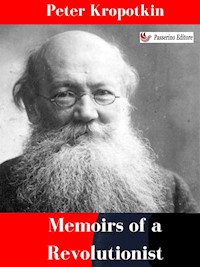

MEMOIRSOF A REVOLUTIONIST

P. KROPOTKIN. 1906.

Photo. by Lavender, Bromley, Kent.

MEMOIRSOF A REVOLUTIONIST

BYP. KROPOTKIN

© 2024 Librorium Editions

ISBN : 9782385747558

This book would not probably have been written for some time to come, were it not for the kind invitation and the most friendly encouragement of the editor and the publisher of the ‘Atlantic Monthly’ to write it for a serial publication in their Review. I feel it a pleasant duty to acknowledge here my very best thanks both for the hospitality that was offered to me, and for the friendly pressure that was exercised in order to induce me to undertake this work. It was published in the ‘Atlantic Monthly’ (September 1898 to September 1899) under the title of ‘Autobiography of a Revolutionist.’ Preparing it now for publication in book form, I have considerably added to the original text in the portions relating to my youth and my stay in Siberia, and especially in the Sixth Part, in which I have narrated my life in Western Europe.

P. K.

October, 1899.

CONTENTS

I.

CHILDHOOD

II.

THE CORPS OF PAGES

III.

SIBERIA

IV.

ST. PETERSBURG—FIRST JOURNEY TO WESTERN EUROPE

V.

THE FORTRESS—THE ESCAPE

VI.

WESTERN EUROPE

PREFACE

The Autobiographies which we owe to great minds have in former times generally been of one of three types: ‘So far I went astray, thus I found the true path’ (St. Augustine); or, ‘So bad was I, but who dares to consider himself better!’ (Rousseau); or, ‘This is the way a genius has slowly been evolved from within and by favourable surroundings’ (Goethe). In these forms of self-representation the author is thus mainly pre-occupied with himself.

In the nineteenth century the autobiographies of men of mark are more often shaped on lines such as these: ‘So full of talent and attractive was I; such appreciation and admiration I won!’ (Johanne Louise Heiberg, ‘A Life lived once more in Reminiscence’); or, ‘I was full of talent and worthy of being loved, but yet I was unappreciated, and these were the hard struggles I went through before I won the crown of fame’ (Hans Christian Andersen, ‘The Tale of a Life’). The main pre-occupation of the writer, in these two classes of life-records, is consequently with what his fellow-men have thought of him and said about him.

The author of the autobiography before us is not pre-occupied with his own capacities, and consequently describes no struggle to gain recognition, Still less does he care for the opinions of his fellow-men about himself; what others have thought of him, he dismisses with a single word.

There is in this work no gazing upon one’s own image. The author is not one of those who willingly speak of themselves; when he does so, it is reluctantly and with a certain shyness. There is here no confession that divulges the inner self, no sentimentality, and no cynicism. The author speaks neither of his sins nor of his virtues; he enters into no vulgar intimacy with his reader. He does not say when he fell in love, and he touches so little upon his relations with the other sex, that he even omits to mention his marriage, and it is only incidentally we learn that he is married at all. That he is a father, and a very loving one, he finds time to mention just once in the rapid review of the last sixteen years of his life.

He is more anxious to give the psychology of his contemporaries than of himself; and one finds in his book the psychology of Russia: the official Russia and the masses underneath—Russia struggling forward and Russia stagnant. He strives to tell the story of his contemporaries rather than his own; and consequently, the record of his life contains the history of Russia during his lifetime, as well as that of the labour movement in Europe during the last half-century. When he plunges into his own inner world, we see the outer world reflected in it.

There is, nevertheless, in this book an effect such as Goethe aimed at in ‘Dichtung und Wahrheit,’ the representation of how a remarkable mind has been shaped; and in analogy with the ‘Confessions’ of St. Augustine, we have the story of an inner crisis which corresponds with what in olden times was called ‘conversion.’ In fact, this inner crisis is the turning point and the core of the book.

There are at this moment only two great Russians who think for the Russian people, and whose thoughts belong to mankind, Leo Tolstoy and Peter Kropotkin. Tolstoy has often told us, in poetical shape, parts of his life. Kropotkin gives us here, for the first time, without any poetical recasting, a rapid survey of his whole career.

However radically different these two men are, there is one parallel which can be drawn between the lives and the views on life of both. Tolstoy is an artist, Kropotkin is a man of science; but there came a period in the career of each of them, when neither could find peace in continuing the work to which he had brought great inborn capacities. Religious considerations led Tolstoy, social considerations led Kropotkin, to abandon the paths they had first taken.

Both are filled with love for mankind; and they are at one in the severe condemnation of the indifference, the thoughtlessness, the crudeness and brutality of the upper classes, as well as in the attraction they both feel towards the life of the downtrodden and ill-used man of the people. Both see more cowardice than stupidity in the world. Both are idealists and both have the reformer’s temperament. Both are peace-loving natures, and Kropotkin is the more peaceful of the two—although Tolstoy always preaches peace and condemns those who take right into their own hands and resort to force, while Kropotkin justifies such action, and was on friendly terms with the Terrorists. The point upon which they differ most is in their attitudes towards the intelligent educated man and towards science altogether; Tolstoy, in his religious passion, disdains and disparages the man equally with the thing, while Kropotkin holds both in high esteem, although at the same time he condemns men of science for forgetting the people and the misery of the masses.

Many a man and many a woman have accomplished a great life-work without having led a great life. Many people are interesting, although their lives may have been quite insignificant and commonplace. Kropotkin’s life is both great and interesting.

In this volume will be found a combination of all the elements out of which an intensely eventful life is composed—idyll and tragedy, drama and romance.

The childhood in Moscow and in the country, the portraits of his mother, sister, and teachers, of the old and trusty servants, together with the many pictures of patriarchal life, are done in such a masterly way that every heart will be touched by them. The landscapes, the story of the unusually intense love between the two brothers—all this is pure idyll.

Side by side there is, unhappily, plenty of sorrow and suffering: the harshness in the family life, the cruel treatment of the serfs, and the narrow-mindedness and heartlessness which are the ruling stars of men’s destinies.

There is variety and there are dramatic catastrophes: life at Court and life in prison; life in the highest Russian society, by the side of emperors and grand dukes, and life in poverty, with the working proletariat, in London and in Switzerland. There are changes of costume as in a drama; the chief actor having to appear during the day in fine dress in the Winter Palace, and in the evening in peasant’s clothes in the suburbs, as a preacher of revolution. And there is, too, the sensational element that belongs to the novel. Although nobody could be simpler in tone and style than Kropotkin, nevertheless parts of his narrative, from the very nature of the events he has to tell, are more intensely exciting than anything in those novels which aim only at being sensational. One reads with breathless interest the preparations for the escape from the hospital of the fortress of St. Paul and St. Peter, and the bold execution of the plan.

Few men have moved, as Kropotkin did, in all layers of society; few know all these layers as he does. What a picture! Kropotkin as a little boy with curled hair, in a fancy-dress costume, standing by the Emperor Nicholas, or running after the Emperor Alexander as his page, with the idea of protecting him. And then again—Kropotkin in a terrible prison, sending away the Grand Duke Nicholas, or listening to the growing insanity of a peasant who is confined in a cell under his very feet.

He has lived the life of the aristocrat and of the worker; he has been one of the Emperor’s pages and a poverty-stricken writer; he has lived the life of the student, the officer, the man of science, the explorer of unknown lands, the administrator, and the hunted revolutionist. In exile he has had at times to live upon bread and tea as a Russian peasant; and he has been exposed to espionage and assassination plots like a Russian emperor.

Few men have had an equally wide field of experience. Just as Kropotkin is able, as a geologist, to survey prehistoric evolution for hundreds of thousands of years past, so too he has assimilated the whole historical evolution of his own times. To the literary and scientific education which is won in the study and in the university (such as the knowledge of languages, belles-lettres, philosophy, and higher mathematics), he added at an early stage of his life that education which is gained in the workshop, in the laboratory, and in the open field—natural science, military science, fortification, knowledge of mechanical and industrial processes. His intellectual equipment is universal.

What must this active mind have suffered when he was reduced to the inactivity of prison life! What a test of endurance and what an exercise in stoicism! Kropotkin says somewhere that a morally developed personality must be at the foundation of every organization. That applies to him. Life has made of him one of the cornerstones for the building of the future.

The crisis in Kropotkin’s life has two turning points which must be mentioned.

He approaches his thirtieth year—the decisive year in a man’s life. With heart and soul he is a man of science; he has made a valuable scientific discovery. He has found out that the maps of Northern Asia are incorrect; that not only the old conceptions of the geography of Asia are wrong, but that the theories of Humboldt are also in contradiction with the facts. For more than two years he has plunged into laborious research. Then, suddenly, on a certain day, the true relations of the facts flash upon him; he understands that the main lines of structure in Asia are not from north to south or from west to east, but from the south-west to the north-east. He submits his discovery to test, he applies it to numerous separated facts, and—it holds its ground. Thus he knew the joy of scientific revelation in its highest and purest form; he has felt how elevating is its action on the mind.

Then comes the crisis. The thought that these joys are the lot of so few, fills him now with sorrow. He asks himself whether he has the right to enjoy this knowledge alone—for himself. He feels that there is a higher duty before him—to do his part in bringing to the mass of the people the information already gained, rather than to work at making new discoveries.

For my part I do not think that he was right. With such conceptions Pasteur would not have been the benefactor of mankind that he has been. After all, everything, in the long run, is to the benefit of the mass of the people. I think that a man does the utmost for the well-being of all when he has given to the world the most intense production of which he is capable. But this fundamental notion is characteristic of Kropotkin; it contains his very essence.

And this attitude of mind carries him farther. In Finland, where he is going to make a new scientific discovery, as he comes to the idea—which was heresy at that time—that in prehistoric ages all Northern Europe was buried under ice, he is so much impressed with compassion for the poor, the suffering, who often know hunger in their struggle for bread, that he considers it his highest, absolute duty to become a teacher and helper of the great working and destitute masses.

Soon after that a new world opens before him—-the life of the working classes—and he learns from those whom he intends to teach.

Five or six years later this crisis appears in its second phase. It happens in Switzerland. Already during his first stay there Kropotkin had abandoned the group of state-socialists, from fear of an economical despotism, from hatred of centralization, from love for the freedom of the individual and the commune. Now, however, after his long imprisonment in Russia, during his second stay amidst the intelligent workers of West Switzerland, the conception which floated before his eyes of a new structure of society, more distinctly dawns upon him in the shape of a society of federated associations, co-operating in the same way as the railway companies, or the postal departments of separate countries co-operate. He knows that he cannot dictate to the future the lines which it will have to follow; he is convinced that all must grow out of the constructive activity of the masses, but he compares, for the sake of illustration, the coming structure with the guilds and the mutual relations which existed in mediæval times, and were worked out from below. He does not believe in the distinction between leaders and led; but I must confess that I am old-fashioned enough to feel pleased when Kropotkin, by a slight inconsistency, says once in praise of a friend that he was ‘a born leader of men.’

The author describes himself as a Revolutionist, and he is surely quite right in so doing. But seldom have there been revolutionists so humane and mild. One feels astounded when, in alluding on one occasion to the possibility of an armed conflict with the Swiss police, there appears in his character the fighting instinct which exists in all of us. He cannot say precisely in this passage whether he and his friends felt a relief at being spared a fight, or a regret that the fight did not take place. This expression of feeling stands alone. He has never been an avenger, but always a martyr.

He does not impose sacrifices upon others; he makes them himself. All his life he has done it, but in such a way that the sacrifice seems to have cost him nothing. So little does he make of it. And with all his energy he is so far from being vindictive, that of a disgusting prison doctor he only remarks: ‘The less said of him the better.’

He is a revolutionist without emphasis and without emblem. He laughs at the oaths and ceremonies with which conspirators bind themselves in dramas and operas. This man is simplicity personified. In character he will bear comparison with any of the fighters for freedom in all lands. None have been more disinterested than he, none have loved mankind more than he does.

But he would not permit me to say in the forefront of his book all the good that I think of him, and should I say it, my words would outrun the limits of a reasonable Preface.

GEORGE BRANDES.

PREFACETO THE SECOND EDITION

When the first edition of this book was brought out at the end of 1899, it was evident to those who had followed the development of affairs in Russia that, owing to the obstinacy of its rulers in refusing to make the necessary concessions in the way of political freedom, the country was rapidly drifting towards a violent revolution. But everything seemed to be so calm on the surface, that when a few of us expressed this idea, we were generally told that we merely took our desires for realities. At the present moment Russia is in full revolution. The old system is falling to pieces, and amidst its ruins the new one is painfully making its way. Meanwhile the defenders of the past are waging a war of extermination against the country—a war which may prolong their rule for a few additional months, but which raises at the same time the passions of the people to a pitch that is full of menaces and danger.

Looked upon in the light of present events, the early movements for freedom which are related in this book acquire a new meaning. They appear as the preparatory phases of the great breakdown of a whole obsolete world—a breakdown which is sure to give a new life to nearly one hundred and fifty million people, and to exercise at the same time a deep and favourable influence upon the march of progress in all Europe and Asia. It seems necessary, therefore, to complete the record of events given in this book by a rapid review of those which have taken place during the last seven years, and were the immediate cause of the present revolution.

The thirteen years of the reign of Alexander III., 1881-1894, were perhaps the gloomiest portion in the nineteenth century history of Russia. Reaction had been growing worse and worse during the last few years of the reign of his father—with the result that a terrible war had been waged against autocracy by the Executive Committee, which had inscribed on its banner political freedom. After the tragic death of Alexander II., his son considered it his duty to make no concessions whatever to the general demand of representative government, and a few weeks after his advent to the throne he solemnly declared his intention of remaining an autocratic ruler of his Empire. And then began a heavy, silent, crushing reaction against all the great, inspiring ideas of Liberty which our generation had lived through at the time of the liberation of the serfs—a reaction, perhaps the more terrible on account of its not being accompanied by striking and revolting acts of violence, but slowly crushing down all the progressive reforms of Alexander II., and the very spirit that bred these reforms, and turning everything, including education, into tools of a general reaction.

Sheer despair got hold of the generation of the Russian ‘intellectuals’ who had to live through that period. The few survivors of the Executive Committee laid down their arms, and there spread in Russian intellectual society that helpless despair, that loss of faith in the forces of ‘the intellectual,’ that general invasion of common-place vulgarity which Tchékhoff has pictured with such a depressing sadness in his novels.

True, that Alexander III., since his advent to the throne, had vaguely understood the importance of several economic questions concerning the welfare of the peasants, and had included them in his programme. But with the set of reactionary advisers whom he had summoned to his aid, and whom he retained throughout his reign, he could accomplish nothing serious; the reactionaries whom he trusted did not at all want to make those serious improvements in the conditions of the peasants which he considered it the mission of autocracy to accomplish; and he would not call in other men, because he knew that they would require a limitation of the powers of autocracy, which he would not admit. When he died, a general feeling of relief went through Russia and the civilized world at large.

Never had a Tsar ascended the throne under more favourable circumstances than Nicholas II. After these thirteen years of reaction, the state of mind in Russia was such, that if Nicholas II. had only mentioned, in his advent manifesto, the intention of taking the advice of his country upon the great questions of inner policy which required an immediate solution, he would have been received with open arms.

The smallest concession would have been gladly accepted as an asset. In fact, the delegates of the Zemstvos, assembled to greet him, asked him only—and this in the most submissive manner—‘to establish a closer intercourse between the Emperor and the provincial representation of the land.’ But instead of accepting this modest invitation, Nicholas II. read before the Zemstvo representatives the insolent speech of reprimand, which had been written for him by Pobiedonostseff, and which expressed his intention of remaining an autocratic ruler of his subjects.

A golden opportunity was thus lost. Distrust became now the dominating note in the relations between the nation and the Tsar, and it was striking to see how this distrust—in one of those indescribable ways in which popular feelings develop—rapidly spread from the Winter Palace to the remotest corners of Russia.

The results of that distrust soon became apparent. The great strikes which broke out at St. Petersburg in 1895, at the time of the coronation of Nicholas II., gave a measure of the depth of discontent which was growing in the masses of the people. The seriousness of the discontent and the unity of action which this revealed were quite unsuspected. What an immense distance was covered since those times, of which I speak in this book, when we used to meet small groups of weavers in the Viborg suburb of St. Petersburg, and asked them with despair if it really was impossible to induce their comrades to join in a strike, so as to obtain a reduction of the hours of labour, which were fourteen and sixteen at that time! Now, the same working-men combined all over St. Petersburg, and brought out of their ranks such speakers and such organisers, as if they had been trade-union hands for ages.

Two years later, in 1897, there were serious disturbances in all the Russian universities; but when a second series of student disturbances began in 1901, they suddenly assumed a quite unexpected political significance. The students protested this time against a law, passed by Nicholas II., who had ordered—again on the advice of Pobiedonostseff—that students implicated in academical disorders should be sent to Port Arthur as soldiers. Hundreds of them were treated accordingly. Formerly, such a movement would have remained a university matter; now it assumed a serious political character and stirred various classes of society. At Moscow the working-men supported the students in their street demonstrations, and fought at their side against the police. At St. Petersburg all sorts of people, including the workmen’s organizations, joined in the street demonstrations, and serious fighting took place in the streets. When the manifestations were dispersed by the lead-weighted horsewhips of the Cossacks, who cut open the faces of men and women assembled in the streets, there was a strikingly unanimous outburst of public indignation.

I have mentioned in this book how tragical was the position of our youth in the seventies and eighties, on account of ‘the fathers’ having abandoned entirely to their sons the terrible task of struggling against a powerful government. Now, ‘the fathers’ joined hands with ‘the sons.’ The ‘respectable’ Society of Authors issued a strongly worded protest. A venerated old member of the Council of the State, Prince Vyazemsky, did the same. Even the officers of the Cossacks of the Bodyguard notified their unwillingness to carry on such police duties. In short, discontent was so general and so openly expressed, that the Committee of Ministers, assuming for the first time since its foundation the rôle of a ‘Ministry,’ discussed the Imperial order concerning the students, and insisted upon, and obtained, its withdrawal.

Something quite unexpected had thus happened. A rash and ill-tempered measure of the young autocrat had thus set all the country on fire. It resulted in two ministers being killed; in bloodshed in the streets of Kharkoff, Moscow and St. Petersburg; and it would have become the cause of further disasters if Nicholas II. had not been prevented from declaring the state of siege in his capital, which surely would have led to still more bloodshed.

All this was pointing to such a deep change in the mind of the nation, that already in the early spring of 1901—long before the declaration of war with Japan—it became evident that the days of autocracy were already counted: ‘Speaking plainly,’ I wrote in the ‘North American Review,’ ‘the fact is that Russia has outgrown the autocratic form of government; and it may be said confidently that if external complications do not disturb the peaceful development of Russia, Nicholas II. will soon be brought to realize that he is bound to take steps for meeting the wishes of the country. Let us hope that he will understand the proper sense of the lesson which he has received during the past two months’ (May 1901, p. 723).

Unfortunately, Nicholas II. understood nothing. He did, on the contrary, everything to bring about the revolution. He contributed to spread discontent everywhere: in Finland, in Poland, in Armenia (by confiscating the property of the Armenian Church), and in Russia itself amongst the peasants, the students, the working-men, the dissenters, and so on. More than that. Efforts were made, on different sides, to induce Nicholas II. to adopt a better policy; but always he himself—so weak for good—found the force to resist these influences. At a decisive moment he always would find enough energy to turn the scales in favour of reaction, by his personal interference. It has been said of him that obstinacy was a distinctive feature of his character, and this seems to be true enough; but he displays it exclusively to oppose those progressive measures which the necessities of the moment render imperative. Even if he occasionally yields to progressive influences, he always manages very soon to counteract them in secrecy. He displays, in fact, precisely those features which necessarily lead to a revolution.

In 1901 it was evident that the old order of things would soon have to be abandoned. The then Minister of Finances, Witte, must have realized it, and he took a step which certainly meant that he was preparing a transition from autocracy to some sort of a half-constitutional régime. The ‘Commissions on the Impoverishment of Agriculture in Central Russia,’ which he convoked in thirty-four provinces, undoubtedly meant to supply that intermediary step, and the country answered to his call in the proper way. Landlords and peasants alike said and maintained quite openly in these Commissions that Russia could not remain any longer under the system of police rule established by Alexander III. Equal rights for all subjects, political liberties, and constitutional guarantees were declared to be an urgent necessity.

Again a splendid opportunity was offered to Nicholas II. for taking a step towards constitutional rule. The Agricultural Commissions had indicated how to do it. Similar committees had to be convoked in all provinces of the Empire, and they would name their representatives who would meet at Moscow and work out the basis of a national representation. And once more Nicholas II. refused to accept that opening. He preferred to follow the counsels of his more intimate advisers, who better expressed his own will. He disowned Witte and called at the head of the Ministry of Interior Von Plehwe—the worst produce of reaction that had been bred by police rule during the reign of Alexander III.!

Even that man did not undertake to maintain autocracy indefinitely; but he undertook to maintain it for ten years more—provided full powers be granted to him, and plenty of money be given—which money he, a pupil of the school of Ignatieff, freely used, it is now known, for organizing the ‘pogroms’—the massacres of the Jews. More than that. Prince Meschersky, the well-known editor of the Grazhdanin—an old man, a Conservative of old standing, and a devotee of the Imperial family—wrote lately in his paper that Plehwe, in order to give a further lease to autocracy, had decided to do his utmost to push Nicholas II. into that terrible war with Japan. Like the Franco-German conflict, the Japanese war was thus the last trump of a decaying Imperial power.

I certainly do not mean that Plehwe’s will was the cause of that war. Its causes lie deeper than that. It became unavoidable the day that Russia got hold of Port Arthur—and even much earlier than that. But this move of Plehwe, and the support he found in his master, are deeply significant for the comprehension of the present events in Russia.

Plehwe was the trump card of autocracy. He was invested with unlimited powers, and used them for placing all Russia under police rule. The State police became the most demoralized and dangerous body in the State. More than 30,000 persons were deported by the police to remote corners of the Empire. Fabulous sums of money were spent for his own protection—but that did not help; he was killed in July 1904, amidst the disasters of the war that he had been so eager to call upon his country. And since that date the events took a new and rapid development. The system of police rule was defeated, and nobody in the Tsar’s surroundings would attempt to continue it.

For six weeks in succession nobody would agree to become the Tsar’s Minister of Interior; and when the Prince Svyatopolk-Mirsky was induced at last to accept it, he did so under the condition that representatives of all the Zemstvos would be convoked at once, to work out a scheme of national representation.

A great agitation spread thereupon in all Russia, when a Congress of the Zemstvos was allowed to come together ‘unofficially’ at Moscow in December 1904. The Zemstvos were quite outspoken in their demands for constitutional guarantees, and their ‘Memorandum’ to the Tsar, signed by 102 representatives out of 104, was soon signed also by numbers of representative persons of different classes in Russia. By-and-by similarly worded ‘Memoranda’ were addressed to the Tsar by the barristers and magistrates, the Assemblies of the Nobility in certain provinces, some municipalities, and so on. The Zemstvo memorandum became thus a sort of ultimatum of the educated portion of the nation, which rapidly organized itself into a number of professional unions. The year 1904 thus ended in a state of great excitement.

Then a new element—the working-men—came to throw the weight of their intervention in favour of the liberating movement. The working-men of St. Petersburg—whom that original personality, Father Gapon, had been most energetically organizing for the preceding twelve months—came to the idea of an immense manifestation which would claim from the Tsar political rights for the workers. On January 22, 1905, they went out—a dense and unarmed crowd of more than 100,000 persons, marching from all the suburbs towards the Winter Palace. Up to that date they had retained an unbroken faith in the good intentions of Nicholas II., and they wanted to tell him themselves of their needs. They trusted him as if he really was their father. But a massacre of these faithful crowds had been prepared beforehand by the military commander of the capital, with all the precautions of modern warfare—local staffs, ambulances, and so on. For a full week the manifestation was openly prepared by Gapon and his aids, and nothing was done by the Government to dissuade the workers from their venture. They marched towards the Palace and crowded round it—sure that the Tsar would appear before them and receive their petition—when the firing began. The troops fired into the dense, absolutely pacific and unarmed crowds, at a range of a few dozen yards, and more than a thousand—perhaps two thousand—men, women and children fell that day, the victims of the Tsar’s fears and obstinacy.

This was how the Russian revolution began, by the extermination of peaceful, trustworthy crowds, and this double character of passive endurance from beneath, and of bloodthirsty extermination from above, it retains up till now. A deep chasm is thus being dug, deeper and deeper every day, between the people and the present rulers, a chasm which—I am inclined to think—never will be filled.

If these massacres were meant to terrorize the masses, they utterly failed in their purpose. Five days after the ‘bloody Vladimir Sunday’ a mass-strike began at Warsaw and similar strikes soon spread all over Poland. All classes of Polish society joined more or less actively in these strikes, which took a formidable extension in the following May. In fact, all the fabric of the State was shattered by these strikes, and the series of massacres which the Russian Government inaugurated in Poland in January and in May 1905, only led to an uninterrupted series of retaliations in which all Polish society evidently stands on the side of the terrorists. The result is, that at the present time Poland is virtually lost to the Russian autocratic Empire. Unless it obtains as complete an autonomy as Finland obtained in 1905, it will not resume its normal life.

Gradually, the revolts began to spread all over Russia. The peasant uprising now assumed serious proportions in different parts of the Empire, everywhere the peasants showing moderation in their demands, together with a great capacity for organized action, but everywhere also insisting upon the necessity of a move in the sense of land nationalization. In the western portion of Georgia (in Transcaucasia) they even organized independent communities, similar to those of the old cantons of Switzerland. At the same time a race-war began in the Caucasus; then came a great uprising at Odessa; the mutiny of the iron-clads of the Black Sea; and a second series of general strikes in Poland, again followed by massacres. And only then, when all Russia was set into open revolt, Nicholas II. finally yielded to the general demands, and announced, in a manifesto issued on the 19th of August, that some sort of national representation would be given to Russia in the shape of a State’s Duma. This was the famous ‘Bulyghin Constitution,’ which granted the right of voting to an infinitesimal fraction only of the population (one man in each 200, even in such wealthy cities as St. Petersburg and Moscow), and entirely excluded 4,000,000 working-men from any participation in the political life of the country. This tardy concession evidently satisfied nobody; it was met with disdain. Mignet, the author of a well-known history of the French Revolution, was right when he wrote that in such times the concessions must come from the Government before any serious bloodshed has taken place. If they come after it, they are useless; the Revolution will take no heed of them and pursue its unavoidable, natural development. So it happened in Russia.

A simple incident—a strike of the bakers at Moscow—was the beginning of a general strike, which soon spread over all Moscow, including all its trades, and from Moscow extended all over Russia. The sufferings of the working-men during that general strike were terrible, but they held out. All traffic on the railways was stopped, and no provisions, no fuel reached Moscow. No newspapers appeared, except the proclamations of the strike committees. Thousands of passengers, tons of letters, mountains of goods accumulated at the stations. St. Petersburg soon joined the strike, and there, too, the workers displayed wonderful powers of organization. No gas, no electric light, no tramways, no water, no cabs, no post, no telegraphs! The factories were silent, the city was plunged in darkness. Then, gradually, the enthusiasm of the poorer classes won the others as well. The shop assistants, the clerks in the banks, the teachers, the actors, the lawyers, the chemists—even the judges joined the strike. A whole country struck against its government, and the strikers kept so strict an order, that they offered no opportunity for military intervention and massacres. Committees of Labour Representatives came into existence, and they were obeyed explicitly by the crowds, 300,000 strong, which filled the streets of St. Petersburg and Moscow.

The panic in the Tsar’s entourage was at a climax. His usual Conservative advisers proved to be as unreliable as the talons rouges were in the surroundings of Louis XVI. Then—only then—Nicholas II. called in Count Witte and agreed on the 30th of October to sign a constitutional manifesto. He declared in it that it was his ‘inflexible will’ ‘to grant to the population the immutable foundations of civic liberty, based on real inviolability of the person, conscience, speech, union, and association.’ For that purpose he ordered to elect a State’s Duma, and promised ‘to establish it as an immutable rule that no law can come into force without the approval of the State Duma,’ and that the people’s representatives ‘should have a real participation in the supervision of the legality of the acts of the authorities appointed by the Crown.’

Two days later, as the crowds which filled the streets of St. Petersburg were going to storm the two chief prisons, Count Witte obtained from him also the granting of an almost general amnesty for political offenders.

These promises produced a tremendous enthusiasm, but, alas, they were soon broken in many important points.

It appears now from an official document, just published—the report of the Head of the Police Department, Lopukhin, to the Premier Minister Stolypin—that at the very moment when the crowds were jubilating in the streets, the Monarchist party organized hired bands for the slaughter of the jubilating crowds. The gendarme officers hurriedly printed with their own hands appeals calling for the massacre ‘of the intellectuals and the Jews,’ and saying that they were the hirelings of the Japanese and the English. Two bishops, Nikon and Nikander, in their pastoral letters, called upon all the ‘true Russians’ ‘to put down the intellectuals by force’; while from the footsteps of the Chapel of the Virgin of Iberia, at Moscow, improvised orators tried to induce the crowds to kill all the students.

More than that. The same Prince Meschersky confessed in his paper—‘with horror’ as he said—that it was a settled plan, hatched among some of the rulers of St. Petersburg, to provoke a serious insurrection, to drown it in blood, and thus ‘to let the Duma die before it was born, so as to return to the old régime.’ ‘Several high functionaries have confessed this to me,’ he adds in his paper.

I have endeavoured in this book to be fair towards Alexander II., and I certainly should like to be equally fair towards Nicholas II., the more as he, besides his own faults, pays for those of his father and grandfather. But I must say that the cordial reception which he gave at that time in his palace to the representatives of the above party, and his protection which they have enjoyed since, were certainly an encouragement to continue on these lines of breeding massacres of innocent people—even if the encouragement be unconscious.

But then came the insurrection at Moscow, in January 1906, provoked to a great extent by the Governor-General, Admiral Dubassoff; the uprising of the peasants in the Baltic provinces against the tyranny of their German landlords; the general strike along the Siberian railway; and a great number (over 1,600) of peasant uprisings in Russia itself; and in all these cases the military repression was accomplished in such terrible forms, including flogging to death, and with such a cruelty, that one could really come to totally despair of civilization, if there were not by the side of these cruelties acts of sublime heroism on behalf of the lovers of freedom.

It was under such conditions that the Duma met in May 1905, to be dissolved after an existence of only seventy days. Its fate evidently had been settled at Peterhof, before it met. A powerful league of all the reactionary elements, lead by Trépoff, who found strong support with Nicholas II. himself, was formed with the firm intention of not allowing the Duma, under any pretext, to exercise a real control upon the actions of the Ministers nominated by the Tsar. And as the Duma strove to obtain this right above all others, it was dissolved.

And now, the condition of Russia is simply beyond description. The items which we have for the first year of ‘Constitutional rule,’ since October 30, 1905, till the same date in 1906, are as follows: Killed in the massacres, shot in the riots, etc., 22,721; condemned to penal servitude, 851 (to an aggregate of 7,138 years); executed, mostly without any semblance of judgment, men, women and youths, 1,518; deported without judgment, mostly to Siberia, 30,000. And the list increases still at the rate of from ten to eighteen every day.

These facts speak for themselves. They talk at Peterhof of maintaining ‘autocracy,’ but there is none left, except that of the eighty governors of the provinces, each of whom is, like an African king, an autocrat in his own domain, so long as his orders please his subordinates. Bloodshed, drumhead military courts, and rapine are flourishing everywhere. Famine is menacing thirty different provinces. And Russia has to go through all that, merely to maintain for a few additional months the irresponsible rule of a camarilla standing round the throne of the Tsar.

How long this state of affairs will last, nobody can foretell. During both the English and the French Revolutions reaction also took for a time the upper hand; in France this lasted nearly two years. But the experience of the last few months has also shown that Russia possesses such a reserve of sound, solid forces in those classes of society upon whom depends the wealth of the country, that the present orgy of White Terror certainly will not last long. The army, which has hitherto been a support of reaction, shows already signs of a better comprehension of its duties towards its mother country; and the crimes of the joined reactionists become too evident not to be understood by the soldiers. As to the revolutionists, after having first minimized the forces of the old régime, they realize them now and prepare for a struggle on a more solid and a broader basis; while the devotion of thousands upon thousands of young men and women is such, that virtually it seems to be inexhaustible. In such conditions, the ultimate victory of those elements which work for the birth of a regenerated, free Russia, is not to be doubted for a moment, especially if they find, as I hope they will, the sympathy and the support of the lovers of Freedom all over the world. Regenerated Russia means a body of some 150,000,000 persons—one-eighth part of the population of the globe, occupying one-sixth part of its continental parts—permitted at last to develop peacefully—a population which, owing to its very composition, is bound to become, not an Empire in the Roman sense of the word, but a Federation of nations combined for the peaceful purposes of civilization and progress.

Bromley, Kent,November, 1906.

PART FIRSTCHILDHOOD

I

Moscow is a city of slow historical growth, and down to the present time its different parts have wonderfully well retained the features which have been stamped upon them in the slow course of history. The Trans-Moskva River district, with its broad, sleepy streets and its monotonous gray painted, low-roofed houses, of which the entrance-gates remain securely bolted day and night, has always been the secluded abode of the merchant class, and the stronghold of the outwardly austere, formalistic, and despotic Nonconformists of the ‘Old Faith.’ The citadel, or Kreml is still the stronghold of Church and State; and the immense space in front of it, covered with thousands of shops and warehouses, has been for centuries a crowded beehive of commerce, and still remains the heart of a great internal trade which spreads over the whole surface of the vast empire. The Tverskáya and the Smiths’ Bridge have been for hundreds of years the chief centres for the fashionable shops; while the artisans’ quarters, the Pluschíkha and the Dorogomílovka, retain the very same features which characterized their uproarious populations in the times of the Moscow Tsars. Each quarter is a little world in itself; each has its own physiognomy, and lives its own separate life. Even the railways, when they made an irruption into the old capital, grouped apart in special centres on the outskirts of the old town their stores and machine-works and their heavily loaded carts and engines.

However, of all parts of Moscow, none, perhaps, is more typical than that labyrinth of clean, quiet, winding streets and lanes which lies at the back of the Kreml, between two great radial streets, the Arbát and the Prechístenka, and is still called the Old Equerries’ Quarter—the Stáraya Konyúshennaya.

Some fifty years ago, there lived in this quarter, and slowly died out, the old Moscow nobility, whose names were so frequently mentioned in the pages of Russian history before the time of Peter I., but who subsequently disappeared to make room for the new-comers, ‘the men of all ranks’—called into service by the founder of the Russian state. Feeling themselves supplanted at the St. Petersburg court, these nobles of the old stock retired either to the Old Equerries’ Quarter in Moscow, or to their picturesque estates in the country round about the capital, and they looked with a sort of contempt and secret jealousy upon the motley crowd of families which came ‘from no one knew where’ to take possession of the highest functions of the government, in the new capital on the banks of the Nevá.

In their younger days most of them had tried their fortunes in the service of the state, chiefly in the army; but for one reason or another they had soon abandoned it, without having risen to high rank. The more successful ones obtained some quiet, almost honorary position in their mother city—my father was one of these—while most of the others simply retired from active service. But wheresoever they might have been shifted, in the course of their careers, over the wide surface of Russia, they always somehow managed to spend their old age in a house of their own in the Old Equerries’ Quarter, under the shadow of the church where they had been baptized, and where the last prayers had been pronounced at the burial of their parents.

New branches budded from the old stocks. Some of them achieved more or less distinction in different parts of Russia; some owned more luxurious houses in the new style in other quarters of Moscow or at St. Petersburg; but the branch which continued to reside in the Old Equerries’ Quarter, somewhere near to the green, the yellow, the pink, or the brown church which was endeared through family associations, was considered as the true representative of the family, irrespective of the position it occupied in the family tree. Its old-fashioned head was treated with great respect, not devoid, I must say, of a slight tinge of irony, even by those younger representatives of the same stock who had left their mother city for a more brilliant career in the St. Petersburg Guards or in the court circles. He personified, for them, the antiquity of the family and its traditions.

In these quiet streets, far away from the noise and bustle of the commercial Moscow, all the houses had much the same appearance. They were mostly built of wood, with bright green sheet-iron roofs, the exteriors stuccoed and decorated with columns and porticoes; all were painted in gay colours. Nearly every house had but one story, with seven or nine big, gay-looking windows facing the street. A second story was admitted only in the back part of the house, which looked upon a spacious yard, surrounded by numbers of small buildings, used as kitchens, stables, cellars, coach-houses, and as dwellings for the retainers and servants. A wide gate opened upon this yard, and a brass plate on it usually bore the inscription, ‘House of So-and-So, Lieutenant or Colonel, and Commander’—very seldom ‘Major-General’ or any similarly elevated civil rank. But if a more luxurious house, embellished by a gilded iron railing and an iron gate, stood in one of those streets, the brass plate on the gate was sure to bear the name of ‘Commerce Counsel’ or ‘Honourable Citizen’ So-and-So. These were the intruders, those who came unasked to settle in this quarter, and were therefore ignored by their neighbours.

No shops were allowed in these select streets, except that in some small wooden house, belonging to the parish church, a tiny grocer’s or greengrocer’s shop might have been found; but then, the policeman’s lodge stood on the opposite corner, and in the daytime the policeman himself, armed with a halberd, would appear at the door to salute with his inoffensive weapon the officers passing by, and would retire inside when dusk came, to employ himself either as a cobbler or in the manufacture of some special stuff patronized by the elder servants of the neighbourhood.

Life went on quietly and peacefully—at least for the outsider—in this Moscow Faubourg Saint-Germain. In the morning nobody was seen in the streets. About midday the children made their appearance under the guidance of French tutors and German nurses, who took them out for a walk on the snow-covered boulevards. Later on in the day the ladies might be seen in their two-horse sledges, with a valet standing behind on a small plank fastened at the end of the runners, or ensconced in an old-fashioned carriage, immense and high, suspended on big curved springs and dragged by four horses, with a postillion in front and two valets standing behind. In the evening most of the houses were brightly illuminated, and, the blinds not being drawn down, the passer-by could admire the card-players or the waltzers in the saloons. ‘Opinions’ were not in vogue in those days, and we were yet far from the years when in each one of these houses a struggle began between ‘fathers and sons’—a struggle that usually ended either in a family tragedy or in a nocturnal visit of the state police. Fifty years ago nothing of the sort was thought of; all was quiet and smooth—at least on the surface.

In this Old Equerries’ Quarter I was born in 1842, and here I passed the first fifteen years of my life. Even after our father had sold the house in which our mother died, and bought another, and when again he had sold that house, and we spent several winters in hired houses, until he had found a third one to his taste within a stone’s-throw of the church where he had been baptized, we still remained in the Old Equerries’ Quarter, leaving it only during the summer to go to our country-seat.

II

A high, spacious bedroom, the corner room of our house, with a wide bed upon which our mother is lying, our baby chairs and tables standing close by, and the neatly served tables covered with sweets and jellies in pretty glass jars—a room into which we children are ushered at a strange hour—-this is the first half-distinct reminiscence of my life.

Our mother was dying of consumption; she was only thirty-five years old. Before parting with us for ever, she had wished to have us by her side, to caress us, to feel happy for a moment in our joys, and she had arranged this little treat by the side of her bed which she could leave no more, I remember her pale thin face, her large, dark brown eyes. She looked at us with love, and invited us to eat, to climb upon her bed; then suddenly she burst into tears and began to cough, and we were told to go.

Some time after, we children—that is, my brother Alexander and myself—were removed from the big house to a small side house in the courtyard. The April sun filled the little rooms with its rays, but our German nurse Madame Búrman and Uliána, our Russian nurse, told us to go to bed. Their faces wet with tears, they were sewing for us black shirts fringed with broad white tassels. We could not sleep: the unknown frightened us, and we listened to their subdued talk. They said something about our mother which we could not understand. We jumped out of our beds, asking, ‘Where is mamma? Where is mamma?’

Both of them burst into sobs, and began to pat our curly heads, calling us ‘poor orphans,’ until Uliána could hold out no longer, and said, ‘Your mother is gone there—to the sky, to the angels.’

‘How to the sky? Why?’ our infantile imagination in vain demanded.

This was in April 1846. I was only three and a half years old, and my brother Sásha not yet five. Where our elder brother and sister, Nicholas and Hélène, had gone I do not know: perhaps they were already at school. Nicholas was twelve years old, Hélène was eleven; they kept together, and we knew them but little. So we remained, Alexander and I, in this little house, in the hands of Madame Búrman and Uliána. The good old German lady, homeless and absolutely alone in the wide world, took toward us the place of our mother. She brought us up as well as she could, buying us from time to time some simple toys, and overfeeding us with ginger cakes whenever another old German, who used to sell such cakes—probably as homeless and solitary as herself—paid an occasional visit to our house. We seldom saw our father, and the next two years passed without leaving any impression on my memory.

III

Our father was very proud of the origin of his family, and would point with solemnity to a piece of parchment which hung on the wall of his study. It was decorated with our arms—the arms of the principality of Smolénsk covered with the ermine mantle and the crown of the Monomáchs—and there was written on it, and certified by the Heraldry Department, that our family originated with a grandson of Rostisláv Mstislávich the Bold (a name familiar in Russian history as that of a Grand Prince of Kíeff), and that our ancestors had been Grand Princes of Smolénsk.

‘It cost me three hundred roubles to obtain that parchment,’ our father used to say. Like most people of his generation, he was not much versed in Russian history, and valued the parchment more for its cost than for its historical associations.

As a matter of fact, our family is of very ancient origin indeed; but, like most descendants of Rurik who may be regarded as representative of the feudal period of Russian history, it was driven into the background when that period ended, and the Románoffs, enthroned at Moscow, began the work of consolidating the Russian state. In recent times, none of the Kropótkins seem to have had any special liking for state functions. Our great-grandfather and grandfather both retired from the military service when quite young men, and hastened to return to their family estates. It must also be said that of these estates the main one, Urúsovo, situated in the government of Ryazán, on a high hill at the border of fertile prairies, might tempt any one by the beauty of its shadowy forests, its winding rivers, and its endless meadows. Our grandfather was only a lieutenant when he left the service, and retired to Urúsovo, devoting himself to his estate, and to the purchase of other estates in the neighbouring provinces.

Probably our generation would have done the same; but our grandfather married a Princess Gagárin, who belonged to a quite different family. Her brother was well known as a passionate lover of the stage. He kept a private theatre of his own, and went so far in his passion as to marry, to the scandal of all his relations, a serf—the genial actress Semyónova, who was one of the creators of dramatic art in Russia, and undoubtedly one of its most sympathetic figures. To the horror of ‘all Moscow,’ she continued to appear on the stage.

I do not know if our grandmother had the same artistic and literary tastes as her brother—I remember her when she was already paralyzed and could speak only in whispers; but it is certain that in the next generation a leaning toward literature became a characteristic of our family. One of the sons of the Princess Gagárin was a minor Russian poet, and issued a book of poems—a fact which my father was ashamed of and always avoided mentioning; and in our own generation several of our cousins, as well as my brother and myself, have contributed more or less to the literature of our period.

Our father was a typical officer of the time of Nicholas I. Not that he was imbued with a warlike spirit or much in love with camp life; I doubt whether he spent a single night of his life at a bivouac fire, or took part in one battle. But under Nicholas I. that was of quite secondary importance. The true military man of those times was the officer who was enamoured of the military uniform and utterly despised all other sorts of attire; whose soldiers were trained to perform almost superhuman tricks with their legs and rifles (to break the wood of the rifle into pieces while ‘presenting arms’ was one of those famous tricks); and who could show on parade a row of soldiers as perfectly aligned and as motionless as a row of toy-soldiers, ‘Very good,’ the Grand Duke Mikhael said once of a regiment, after having kept it for one hour presenting arms—‘only they breathe!’ To respond to the then current conception of a military man was certainly our father’s ideal.

True, he took part in the Turkish campaign of 1828; but he managed to remain all the time on the staff of the chief commander; and if we children, taking advantage of a moment when he was in a particularly good temper, asked him to tell us something about the war, he had nothing to tell but of a fierce attack of hundreds of Turkish dogs which one night assailed him and his faithful servant, Frol, as they were riding with despatches through an abandoned Turkish village. They had to use swords to extricate themselves from the hungry beasts. Bands of Turks would assuredly have better satisfied our imagination, but we accepted the dogs as a substitute. When, however, pressed by our questions, our father told us how he had won the cross of Saint Anne ‘for gallantry,’ and the golden sword which he wore, I must confess we felt really disappointed. His story was decidedly too prosaic. The officers of the general staff were lodged in a Turkish village, when it took fire. In a moment the houses were enveloped in flames, and in one of them a child had been left behind. Its mother uttered despairing cries. Thereupon, Frol, who always accompanied his master, rushed into the flames and saved the child. The chief commander, who saw the act, at once gave father the cross for gallantry.

‘But, father,’ we exclaimed, ‘it was Frol who saved the child!’

‘What of that?’ replied he, in the most naïve way. ‘Was he not my man? It is all the same.’

He also took some part in the campaign of 1831, during the Polish Revolution, and in Warsaw he made the acquaintance of, and fell in love with, the youngest daughter of the commander of an army corps, General Sulíma. The marriage was celebrated with great pomp, in the Lazienki palace; the lieutenant-governor, Count Paskiéwich, acting as nuptial godfather on the bridegroom’s side. ‘But your mother,’ our father used to add, ‘brought me no fortune whatever.’