9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

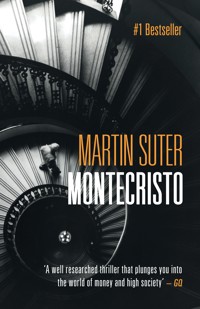

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

Video journalist Jonas Brand is on a rail journey from Zurich to Basel when stock trader Paolo Contini appears to throw himself from the train to his death. Brand sets his footage of the aftermath of the incident aside to investigate a strange coincidence: two 100-Swiss-franc banknotes bearing the same serial number have come into his possession. Sensing an opportunity to graduate from celebrity journalism to serious investigation, he has the banknotes analysed, with bizarrely contradictory... and fatal results. Set in the tangled world of finance, politics and the media, Montecristo is a pacy conspiracy thriller full of betrayal and underhand tactics - a sharp and entertaining demonstration of the topical maxim that some banks are simply 'too big to fail'.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

MONTECRISTO

Video journalist Jonas Brand is on a rail journey from Zurich to Basel when stock trader Paolo Contini appears to throw himself from the train to his death. Brand sets his footage of the aftermath of the incident aside to investigate a strange coincidence: two 100-Swiss-franc banknotes bearing the same serial number have come into his possession. Sensing an opportunity to graduate from celebrity journalism to serious investigation, he has the banknotes analysed, with bizarrely contradictory... and fatal results.

Set in the tangled world of finance, politics and the media, Montecristo is a pacy conspiracy thriller full of betrayal and underhand tactics – a sharp and entertaining demonstration of the topical maxim that some banks are simply ‘too big to fail.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Martin Suter is a writer, columnist and screenwriter. Until 1991 he worked as a creative director in advertising, before deciding to focus exclusively on writing. His previous novels (most recentlyThe Time, The Time)have enjoyed huge international success, selling over 7 million copies with numerous number ones, and have been published in thirty-two languages. Martin lives in Zurich with his family.

MARTIN SUTER – AWARD WINNING AUTHOR

Small World – 1997

Swiss Award for culture, 1997, Ehrengabe des Kantons Zurich

A Deal with the Devil (aka The Devil from Milan) – 2006

Friedrich Glauser award for best novel

Montecristo – 2015

Literary Prize of the Economic Club at the House of Literature

BESTSELLERS

Montecristo – #1 Spiegel Bestseller, #6 overall Spiegel for 2015 The Time, the Time – Spiegel Bestseller

Allmen and the Dahlias – Spiegel Bestseller

Allmen and the Vanished Maria – Top ten Bestseller in Germany and Switzerland

The Chef – #1 Bestseller in Germany, Switzerland and Austria at the same time

TV AND FILM ADAPTATIONS

A Perfect Friend – 2006, Film adaptation

Small World – 2010, Film adaptation

Lila, Lila – 2008, Film adaptation

The Chef – 2014, Film adaptation

The Devil from Milan – 2011, TV adaptation

The Dark Side of the Moon – 2015, Film adaptation

Allmen and the Dragonflies – 2016, TV adaptation

Allmen and thePink Diamond –2016, TV adaptation

‘Martin Suter will always surprise you. Each new novel is a challenge and an adventure’ – Les Echos

‘There is charm, irony and undeniable elegance in the novels of Martin Suter, who is probably one of the best contemporary authors’ – Le Nouvel Observateur

‘An exceptionally gripping, well written book, the type you don’t want to put down until you find out how the showdown ends’ – Handelsblatt

‘Martin Suter’s thriller plunges into the world of money and high society. So well researched that you can’t help but reconsider the good old method of keeping your savings tucked away under the mattress’ – GQ, Munich

‘A fast-paced novel with a finale reminiscent of Dürrenmatt. This is Suter’s most political novel so far’ – ZDF

‘The narrative is action-packed and leaves out absolutely none of the genre’s typical thrills…and the reader learns a great deal about banks and monetary policy along the way…’ – Stern

‘A thriller, set in the banking world, which reveals that our financial system is still built on sand’ – ORF Vienna

‘Martin Suter’s thriller is wry, cryptic and action-packed. If you love crime thrillers, then don’t miss this!’ – Emotion, Hamburg

‘In Montecristo the author remains true to his usual elegant style and polished dialogue’ – Spiegel Online

‘A holiday read of the very highest quality. Excellently researched, as usual, and apparently checked for authenticity by those in the know’ – Tages-Anzeiger, Zurich

‘Taking visible pleasure in the plotting and detail, Martin Suter has created a smooth, character-rich play of intrigue which is easily understood despite the complex material, and has well-known names to vouch for its authenticity’ – Neue Zürcher Zeitung

‘Martin Suter’s gaze is fresh and wicked, his ear for dialogue infallible. Quite simply, his works are literary genius’ – Die Wochenzeitung

‘Martin Suter reaches a huge readership with his novels. He writes exciting, well constructed, almost cinematic, stories; he catches his readers with ingenious, streamlined plots’ – Der Spiegel

‘Suter is fond of dramatic turns of events with a psychological undertone’ – Matthieu London, Libération

For Toni

Part One

1

The train jolted. Glassesand bottles flew from tables, while the deafening whistle of the engine and the screech of metal on metal accompanied the clattering, shouting and clinking in the buffet car. Until everything fell silent with another jolt.

It was pitch black outside. They were in a tunnel.

The silence was broken by the obligatory joker: ‘Are we there yet?’

A few passengers laughed, then everybody started speaking at once and wiping the beer and wine from tables, clothes, handbags and briefcases.

‘Emergency brake,’ someone stated.

Jonas Brand was sitting in the buffet car of the five-thirty intercity to Basel, surrounded by regulars – commuters who had the same conversations over the same drink every evening, some of them for years. The carriage was thick with the stale odour of alcohol, smoke-impregnated suits, sweat and the almost dissipated notes of men’s aftershaves.

His overweight neighbour, who’d managed to rescue the laptop he’d been gawping at the entire journey, sighed, ‘Customer incident.’

Jonas got up to recover the camera rucksack he’d put on the floor beside him, and which had slid some way down the aisle when the train came to an abrupt halt. His camcorder was undamaged, even though as usual he’d failed to pack it away carefully.

He knew what ‘customer incident’ meant: someone had thrown themselves under the train. Jonas had been on another train a few years back when this happened, and once more he felt a shivering sensation rising from his feet to his neck.

At the rear of the buffet car some passengers were attending to the waiter, who had a cut on his head. Someone was trying to stop the bleeding with a napkin.

Nobody paid heed to the pallid young man who entered the restaurant car, looking around in search of something. He walked past all the tables to the other end of the carriage where Jonas was sitting, almost bumping into the conductress who rushed in and shouted, ‘Who pulled the emergency brake?’

Only now did his fellow passengers notice the man. For he answered with a defiant ‘Me!’

The conductress gave him a stern look. The man was a good head taller than her. He wore a sleek-cut suit with trousers whose turn-ups sat a finger’s width over his pointed shoes.

‘Why?’

Now he was standing beside Jonas, who could see how pale and agitated the young man was. ‘Somebody fell out,’ he stammered.

‘Where?’ the conductor asked.

‘Back there,’ the young man replied, pointing to where he’d come from. She led the way and he followed.

Taking his camera and shoulder rig from the rucksack, Jonas followed the two of them.

Stopping by the nearest exit, the man explained how he’d been standing there waiting for the loo to become free. He’d looked out of the window and all of a sudden something had flown past, like a large mannequin, and smashed against the tunnel wall. He’d only seen it for a moment, in the faint light through the train window. But he was sure it was a person; it had a face.

Jonas had the camera on his shoulder and was filming.

‘Please stop that,’ the conductress said.

Without breaking from filming he showed her his press pass.

‘Television,’ he explained.

The woman let him continue. She went on her way through a full second-class carriage. The passengers were sitting down, resigned to the delay. Because of the cameraman’s presence nobody asked the conductress what had happened.

The next exit was not fully closed. Someone had pulled the emergency release to open the door. The conductor opened it fully and they were met by the smell of damp rock and metal dust.

Jonas filmed the tunnel which was dimly lit by the light from inside the train. Taking a step down, he focused the lens on the rear carriages. In the murky distance he could make out a shape in the narrow gap between the train and the tunnel wall. He couldn’t say what it was; he didn’t have the right lens.

*

At this point a hard-nosed video journalist would have got out to film the bundle at close range. But Jonas Brand was not hard-nosed. He wasn’t even a real video journalist. He’d only landed in this job after a sequence of coincidences. As he liked to see it, it was a stopover on his way to becoming a film director.

But Jonas had been on this journey for quite a while now. Ever since he’d left school, to be precise. After falling out with his parents he’d hung around film sets, jobbing as a runner, cable puller and production driver. He learned about lighting and made it to the position of best boy. With the money he earned he financed a cinematography course at the London Film School and after that worked as a camera assistant. His CV since then included a few feature films, a handful of documentaries and an increasing number of advertisements.

Once he stepped in as cameraman for a sick colleague and filmed a few reports about the World Economic Forum. When the editor on that job switched to a local TV channel he started giving Jonas the occasional commission. Soon Brand was a permanent fixture on the team, and when the broadcaster introduced the role of video journalist as a cost-cutting measure, the man responsible for the words was dropped, while the one responsible for the pictures was retained. And so Jonas Brand inadvertently became a video journalist.

Regarding this job merely as a temporary solution, he hadn’t progressed very far. Jonas plodded along without much ambition, content to produce sound work. True, he was soon able to go freelance and became known as a safe pair of hands if the emphasis was on punctuality, reliability and economy. But where creativity was called for, Jonas Brand, now almost forty, would always be second choice.

He was enough of a video journalist, however, to turn on his camera and document this uncomfortable episode.

The cheerful early-evening atmosphere in the restaurant car had subsided and been replaced by a combination of impatience and tedium. Few words were exchanged; everyone was waiting for an announcement.

But when it came, preceded by some ear-piercing feedback, most passengers were startled.

‘Due to a customer incident this train will remain stationary for the time being,’ the conductress’s voice said. ‘We apologise for any inconvenience.’

The announcement was immediately followed by sighs of resignation from the seasoned commuters, mixed with anxious questions from the new faces. ‘Customer incident?’

‘It means someone’s gone under the train. We could be here for hours.’

Jonas went from table to table, interviewing the passengers. Some demanded to see his press pass, while two didn’t want to be filmed or interviewed. But most of them were pleased for some distraction and happy to respond to his questions.

‘It’s terrible to think that someone’s lying down there squashed.’

‘This must be the tenth time it’s happened to me in six years of commuting. I get the feeling it’s on the increase.’

‘I think it’s plain rude to kill yourself like that. There are other ways, ones that don’t ruin the evenings of a few hundred non-depressives.’

‘Jumped off the train? He could have waited till we got out of the tunnel.’

‘Or she.’

The waiter, now with a plaster on his forehead, was taking orders again. He was a short, tubby Tamil who the regulars called Padman. He spoke a carefree Swiss German and smiled into Jonas’s camera with a magnificent set of teeth. Yes, he explained, this was a regular occurrence. The good life that the Swiss people enjoyed must be unbearable.

The overweight man who’d been sitting next to Jonas had buried himself in his laptop again. He had no objections to being filmed, but didn’t want to say anything. Jonas focused on him as he moved down the carriage. The atmosphere was now quite subdued. The few people who were talking spoke softly.

A man in a business suit got up from a table, came towards Jonas, filling the screen before walking past. Jonas heard him ask, ‘Have you seen Paolo?’

Jonas panned back to the fat man, who replied without looking up from his laptop, ‘Wasn’t he sitting with you?’

‘His phone rang and he went out to take the call. But he never came back.’

The fat man finally looked up to his acquaintance in the business suit, shrugged and said, ‘Maybe he’s the customer incident.’

The man shook his head and returned to his table. Jonas was convinced he’d muttered ‘Arsehole’ under his breath.

*

He was on his way to Basel for a fundraising event, where with much fanfare the great and good of the city made a not particularly large sum of money for a charitable cause which changed each year. He’d forgotten who the beneficiary was this time.

His coverage of the event was a bread-and-butter job commissioned by ‘Highlife’, a public-service TV lifestyle magazine, and one of his best clients, if not his favourite one.

It was past nine o’clock when Jonas finally arrived at the hotel where the charity ball was being held. He’d been in regular phone contact with the promoter’s PR lady, who sounded as if she regarded the incident as a targeted attack on her event, and postponed the auction several times.

Most of the lots had nonetheless been auctioned by the time he found his way into the ballroom. At the climax of the evening, a ‘VIM’ poster by Niklaus Stoecklin from 1929, which soared to the inflated price of eleven thousand francs, Jonas had to change his battery because of the unscheduled footage he’d taken of the customer incident. He missed the fall of the hammer, for which the buyer posed expressly. Jonas pretended to be filming, giving a casual nod when the press woman asked, ‘Did you get that?’

*

It was the beginning of a warm December, full of incongruous-looking Christmas decorations and busy street cafés.

Two and a half months had passed since the incident on the intercity. This had led to a reprimand for Jonas from ‘Highlife’, his client. The PR agency in charge of the charity ball had complained that the most important moment of the evening, the purchase of the main lot, was missing from his report.

The material from the railway carriage lay unused together with the other fragments that one day Jonas planned to assemble into a major documentary. Entitled ‘On the sidelines’, it was going to be a black-and-white film presenting the impressions of a video journalist.

All that had been said about the customer incident was that it was a passenger suicide. The privacy laws had drawn a veil over any further details.

*

Jonas was in an excellent mood, and this was down to Marina Ruiz.

He had met Marina all of two hours ago, but had already arranged to see her again. Things never usually happened so quickly for him, but this rendezvous was less of a date and more the next stage of a conspiracy.

Marina was a tall woman from Zürich with straight, shoulder-length hair and oriental features. She worked for the events agency in charge of the film première that Jonas was compiling a report on. The film was being released simultaneously in a number of European cities, and only a few supporting actors were left as the star guests for the Zürich première. One of them, Melinda Trueheart, had been assigned to the care of Marina, who was tasked with accompanying the actress to interviews and shooing away the imaginary fans.

In interview Miss Trueheart proved to be an appallingly affected individual. While Jonas tried to ask relatively serious questions, Marina, who stood behind her, started miming and making fun of her answers. It was so astonishing and so funny that Jonas kept losing his composure. Each time he laughed out loud the starlet turned around to her PR woman for help.

And each time Marina managed to pull an earnest, concerned face at the last moment, which in itself was so amusing that Jonas couldn’t help laughing again.

Melinda Trueheart wasn’t sure whether the presenter was making fun of her or simply had a comic interviewing style. Gradually she began laughing too, and providing witty answers. By the end her affectation had practically vanished and the result was a surprisingly entertaining piece.

Marina led her ward away. As Jonas was packing up his gear she returned.

‘May I invite you to dinner?’ he asked.

‘I thought you’d never ask,’ she replied.

*

The following evening they met in a new Indian restaurant. It didn’t appear that word had got around yet, because the place was half empty.

Jonas had suggested the restaurant because he loved Indian food and he hoped his expertise in this area might create something of an impression. But Marina turned out to be a connoisseur too, or at least enough of one to see that the menu was far too long and the dishes deep-frozen and reheated in the microwave.

To begin with they spoke in hushed voices like all the other diners. But Marina had that ability to focus so exclusively on another person that they quickly forgot their surroundings. Jonas told her things he would never normally talk about. She soon learned that he was thirty-eight years old, he’d divorced six years previously, had been a freelance video journalist for eight, and deep down was a filmmaker.

‘Filmmaker?’ Marina pushed her plate to one side – a stringy mutton buhari – leaned forward on her crossed arms and buried her gaze more deeply into his.

And so he came to tell her about Montecristo.

‘The story is based on The Count of Monte Cristo, but it takes place now. There’s this young man who’s made millions from a dotcom company he’s founded. While on holiday in Thailand a large quantity of heroin is slipped into his luggage. He’s caught and sent to prison as a dealer. He’s facing the death penalty or life imprisonment. The case causes a stir back home, but when his three business partners, who his lawyer has called as witnesses, surprisingly incriminate him, the public loses interest. The man is sentenced to life imprisonment and vanishes into one of Thailand’s notorious prisons. His business partners gain control over the firm and sell it for a fortune.’

Jonas took a sip of his beer.

‘Go on,’ Marina urged.

‘The man…’

‘What’s his name?’

‘Till now I’ve called him “Montecristo”. Do you think that’s over-egging it?’

‘Can’t tell yet. Go on.’

‘A few years later Montecristo manages to escape. He’s still got plenty of money put aside from before, and now he uses it to exact his revenge. He undergoes a number of cosmetic operations, creates a new identity for himself and travels back home. The rest of the film shows how Montecristo, in the guise of an investor, ruins his three former partners.’

‘They’re the ones who smuggled the heroin into his luggage, right?’

‘Arranged for it to be put there, exactly.’

For the first time since he’d started talking Marina turned her green eyes away from Jonas, looked at her glass and took a sip. After seeing the wine list she’d also plumped for an Indian Kingfisher beer.

She gave Jonas her undivided attention once more. ‘You know that with the right cast that could be a blockbuster.’

Jonas gave a grim smile. ‘With the right cast, the right screenplay, the right director and right producer.’

Marina nodded thoughtfully. ‘How long have you been working on this project?’

Jonas poured out the rest of the beer from their bottles. ‘Gross time or net?’ he asked.

‘Both.’

‘I wrote the first sketch of the story in a single night. So about twelve hours net. That was in 2009. So six years gross.’

‘And no one’s shown any interest?’

‘That’s what the film business is like. Everyone wants experience, but nobody lets you get any.’

Marina gave a knowing smile. ‘And by the time you’ve got some you’re too old.’

‘How do you know that?’ Jonas asked in astonishment.

‘It’s what my stepfather always says.’

‘Is he in films too?’

‘He’s a careers adviser.’

*

As Marina’s flat was close to the restaurant, they walked back. The Föhn was blowing that night; a hefty wind shook the Christmas decorations of the Turkish, Tamil and Italian shops they passed. Marina had taken his arm and they strolled through the night like a happily married couple on their way home.

She was a tall woman, and the high heels she wore made her a touch taller than Jonas. Right from the start he’d felt very comfortable in her presence, and this feeling now intensified as she walked on his arm, delicately and affectionately, in spite of her height.

She let go of his arm by the entrance to a modern apartment block and fished a key from her handbag. Wearing the same smile that he’d found so funny during his interview with the starlet, she waited for him to say something.

Somewhat embarrassed, he said, ‘I assume you don’t invite men up for a nightcap on a first date.’

‘Oh I do,’ she replied. ‘But never those I want to see again.’ Taking his head she pulled it towards her and gave him a fleeting kiss on the lips. He put his hands around her waist, but she took them away, unlocked the door and slipped into the entrance hall.

*

Too excited just to take a taxi and go to bed, he set off on foot in the direction of his flat, which was in a different area altogether. He would let inspiration be his guide and then either hail a cab, pop in somewhere for a drink or saunter back the entire way.

The Föhn was still driving its capricious gusts through the unprepossessing streets. Here and there, scattered supporters of a victorious football team bellowed into the night, and smokers stretched their legs outside night clubs.

Jonas had been through several relationships since his divorce, but he’d never been as enchanted as on this unhospitable evening.

Arriving at the main train station, he took the shortcut through the concourse, where there was the usual mixture of movement and inertia. People from the sticks who’d spent the evening in town were hurrying to get their trains back. Commuters who’d been working late met them going in the other direction. And amidst this coming and going, the usual station folk hung around, people who’d come from nowhere and were going nowhere.

There was hardly a soul in the street outside. The wind set in motion the hundred-and-fifty thousand LED lights overhead, but they still paled against the bright Christmas illuminations and advertisements of the shops.

Deep in thought, Jonas passed the watch and jewellery shops, and the plant troughs and boulders that protected these establishments from being ram-raided.

At the next stop he saw one of the last trams that was heading to his part of town. He got on and leaned against the window at the back of the carriage, even though it was almost empty. Jonas was still full of beans and had no desire to sit.

The handful of passengers were absorbed in themselves. The silence was only broken by the announcements of the successive stops and possible transport connections.

Like a spaceship, Jonas thought, gliding through the nocturnal unreality of the fancy shops and venerable big banks. Two worlds unfamiliar to each other.

The lake dimly reflected the brightness of the streetlights and sporadic night-time traffic. The Föhn rippled the surface of the water, shaking the jetties of the closed boat-hire places and the wrapped-up boats.

A few passengers got off, a few got on, and the journey continued on its way, past the opera house and small station, and into his neighbourhood.

Jonas got out. He wanted to walk the last two stops home. Which would also leave open the option of spontaneously popping into Cesare’s.

An option he took. Nodding to a smoker by the door he knew by sight, he went in. The volume of the music suggested the place was busier than it actually was. A few drinkers were chatting at the bar and a few tables were still occupied. Here two people in a serious discussion, there a couple who hadn’t yet decided on his place or hers.

Jonas went to one of the bar tables. An Italian waiter asked him what he’d like to drink. He stuck with beer.

A young woman came over. She was holding a glass with more greenery than liquid, and having trouble maintaining her balance in her stilettos. ‘I know you,’ she said, putting her drink down next to his beer.

People would occasionally recognise him because he sometimes edited himself into an interview to make it appear more natural, but also to get a bit of screen presence. It facilitated access to the semi-important people and could be helpful in these sorts of situations.

This was not one of those evenings, however.

The woman was pretty in a rather conventional sort of way. She wore more make-up than was necessary and had clearly reapplied her lipstick in advance of this encounter. ‘You’re from Highlife, aren’t you?’ she asserted.

He shook his head and took a large gulp of beer to show her that he wasn’t planning on staying long.

‘But I’ve seen you on Highlife. You’re a reporter.’

‘You may have done; I do the odd bit of work for them,’ he replied, looking around for the waiter.

She looked him in the eye and said, ‘In a hurry?’

‘Sort of.’

The woman nodded ironically. ‘Just in urgent need of one last beer. I know what it’s like.’

The waiter came and put his heavy purse on the table. ‘All on the same bill?’

‘We haven’t known each other long enough for that,’ Jonas said.

‘I’ve got plenty of time,’ she pouted.

Brand looked in his wallet for six francs, but all he could find was a little change and a two-hundred. ‘Sorry, I haven’t anything smaller.’

‘That’s OK. It makes it quicker to count up when I clock off,’ the waiter said, giving him his change.

The woman with the empty glass watched the notes changing hands. ‘Some have time, others money.’

Jonas couldn’t help laughing. Pointing to her glass he said, ‘And another one of whatever that was.’

‘A mojito,’ she said. ‘But you’ve got to have a drink with me.’

He waited until the waiter returned with her mojito, toasted her with his last sip of beer and wished her goodnight.

‘Shame,’ she said, before looking around for someone else.

*

It was no more than ten minutes to his flat. The wind storm had become so violent that Jonas carefully avoided the pavements close to house fronts. The Föhn clattered and creaked in balconies, roared through bare trees lining the streets and hammered unfastened shutters.

Number 73 Rofflerstrasse was a four-storey brick building from the 1930s. The entrance was behind a narrow, neglected front garden, and flanked by four ugly, standard aluminium post boxes on either side, which had been added later. Jonas collected his post and went up the three steps to the front door.

Acquiring his flat had been one of those instances when his presence on screen had come in handy. At the viewing a queue of interested parties had lined the steps, as affordable period flats with high ceilings were a rarity in this part of town. The elderly lady from the property management company had recognised him. Although she hadn’t actually said anything, Jonas had developed an inkling for whether someone recognised him from television.

At any rate, he was preferred to all the couples and families, even though on the questionnaire he’d made no secret of the fact that he was divorced and still single.

To liven up the three rooms and generous hallway, he’d furnished and decorated them with everything he’d been able to lay his hands on. Jonas became a regular customer of the city’s second-hand shops, flea markets and junk dealers.

Brand was a collector without an overarching plan. He bought Asiatica, militaria, porcelain, folk art, textiles, posters, trinkets, photographs, kidney tables, tubular furniture, crystal chandeliers – simply anything he liked the look of or found striking.

This unsystematic collecting fury gave his flat a rather museum-like cosiness, which didn’t suit him particularly well as his style was basically unfussy and straightforward. But sometimes he had the feeling that he was starting to adapt to his surroundings.

He hung his coat on the round stand that looked as if it had come straight out of a 1950s school staffroom, went into the sitting room and embarked on his lighting ceremony. The room didn’t have a central ceiling light, but was full of desk and wall lamps, standard lamps, spots and floor lights. A neon sign for a club called ‘Chérie’ and an illuminated Michelin man served as further light sources.

Jonas switched everything on, made himself a green tea and lit a sandalwood incense stick.

On one of his forays he’d come across a small collection of bizarre incense-stick holders. Nymphs at the end of elongated ponds, which caught the ashes; leisurely looking skeletons, whose eye sockets accommodated the incense sticks; or dragons into whose jaws the sticks were inserted like spears. He’d acquired the entire collection for a very good price, and as a bonus the stallholder had given him a handful of boxes with different perfumes of incense. Which made him doubt that he’d got such a bargain after all. But he did acquire a taste for incense.

He sat in a leather armchair which he’d covered with a kanga to hide the damaged patches. This printed garment showed a green palm tree and four coconuts on a yellow background with the writing: Naogopa simba na meno yake siogopi mtu kwa maneno yake. Which was Swahili for ‘I fear a lion with its strong teeth, but not a man with his words.’

Jonas grabbed the remote control, turned on the stereo and gave a start. The guitar intro to Bob Dylan’s ‘Man in the Long Black Coat’ tore through the silence at full volume.

The volume setting was from one of those sentimental evenings which sometimes came upon him and degenerated into a session with too much alcohol and too loud music. Infrequent and always occurring without prior warning, they were characteristic of the loneliness of the single man. If he were being honest, he even quite enjoyed them.

Jonas turned down the volume, stood up and put on something that better suited his mood. He wasn’t sad, or at most only a touch sad that she hadn’t invited him up.

Marina had elicited things from him that he had scarcely told anyone else. He very seldom spoke about himself, and whenever he did he always felt bad later, like after an evening with excessive alcohol and hazy recollections.

But this time there was no bad aftertaste. He’d been at ease from the outset and it had felt perfectly normal to talk about himself.

It was as if he’d known Marina for years. He’d never felt anything like this before and, now alone in his flat, he was still buoyed by their encounter.

Going into the kitchen he made himself another tea. As he listened to the kettle getting louder his gaze fell on the notebook that belonged to Frau Knezevic, his Croatian cleaning lady. It lay on top of the espresso machine, precisely where Jonas couldn’t miss it. This meant that the money he left inside the book was now all gone. Or even that she’d had to pay for things out of her own pocket. Not much, surely, for he suspected that she always did a little shopping at the right time just to give him a bad conscience.

He took his tea and the notebook into the sitting room. It bulged with all the receipts and lists it contained. Brand would check her calculations each time, even though he’d never yet discovered a mistake. He didn’t want Frau Knezevic to think that he wasn’t concerned about a few francs here or there. Even though that wouldn’t be entirely wrong.

Money wasn’t especially important to Jonas. Not because he had a lot of it, but because for him it was no more than a means to enjoying a more or less comfortable life and taking the odd holiday. He didn’t regard his car as a status symbol either. It was only of interest to Jonas as a means of getting himself and his gear from A to B, and thus he’d never made an effort to keep his diesel VW Passat, almost ten years old now, looking pristine.

Brand’s indifference to money might cause him to lose track of his finances, risking a call from Herr Weber, the long-serving and amicable account manager at his bank, because he’d gone overdrawn.

Every September when his tax declaration was due, he also strained the nerves of the bookkeeper at his company, Brand Productions, because he was sloppy about making a strict distinction between business and private accounting, and mixed up or mismatched his receipts.

But he was always precise when it came to Frau Knezevic, taking great care to add up every item.

He owed her eight francs. He placed a pedantic tick by the balance sum, scrunched up the receipts and threw them in the bin. He would always refill Frau Knezevic’s empty coffers with two hundred francs. Opening his wallet all he could find was the hundred plus the change the waiter at Cesare’s had given him, so he had to go to the safe.

Brand’s safe was in his bedroom, beside a wall full of butterflies mounted under glass. It was a statue from Vietnam, a seated woman in a green-lacquered dress with bronze trim and a matching turban. He’d bought it from an antiques dealer in Saigon who’d told him it was a mother goddess from an ancient Vietnamese folk religion.

Part of the stole could be detached at the back of the statue, revealing beneath a lid varnished in exactly the same lacquer as the rest of the dress. If you pressed the edge in the right place the opposite edge would slide up enough for you to take hold of it and remove the lid. Behind this was a hollow opening measuring about nine centimetres by nine. This was where the woman’s soul had once lived, the antiques dealer had told him. When she swapped her existence as a goddess for that of a figurine the soul had taken flight. The empty space now provided enough space for a few banknotes.

Currently there was just one hundred in there. Taking it, Jonas returned to the sitting room and placed it beside the other one inside the notebook, on the front of which Frau Knezevic had written ‘Cash’ in her rather childish hand.

There they lay, the two banknotes. On the right, the portrait of Alberto Giacometti, who always appeared to Jonas as if he had a blocked nose and had to breathe through his slightly opened mouth; on the left, his most famous sculpture, L’homme qui marche (The Walking Man), who looked to Jonas as if he’d just swung his right leg over the barrier of digits that comprised the banknote’s serial number. The last seven digits would have made a pleasing telephone number: 200 44 88.

Startled by a loud crash, Jonas ran into the kitchen. The Föhn had blasted open the upper part of the kitchen window, whose catch hadn’t been properly fastened. Jonas closed it and calmly went back into the sitting room.

The gust of wind had blown the notes from the table. The one with the serial number ending in 200 44 88 was right beside the armchair he’d been sitting in.

He found the other one under the flower stand beside the window, in which a fern was fighting for survival. Picking up the errant banknote, he examined it and noticed the last seven digits: 200 44 88.

What a strange coincidence, he thought, comparing the two notes. He wasn’t mistaken. The last seven digits were identical. And not only that – the first three characters were the same too! Both hundred notes had the serial number 07E2004488.

What could that mean? Only one thing, according to Brand’s layman’s amateur knowledge of banknotes: one of the two had to be fake.

He took them to his studio, as he called his study. Unlike the rest of the flat it was decorated very soberly. White office furniture and matching shelves with carefully labelled archive boxes. The heart of the studio was the editing area: a large, tidy desk with two flat screens, a keyboard and a mouse. In front of the desk stood a shiny chrome executive chair with leather upholstery, which he’d bought a couple of years ago after suffering a prolapsed disc, and was occasionally embarrassed about when visitors came round.

He took out a magnifying glass from the top drawer of the mobile filing cabinet, switched on the desk lamp, pointed it at the banknotes and examined them. Which one was fake?

Jonas couldn’t see any difference, but then again he didn’t know what he was looking for. One of the hundreds felt newer and crisper; it was the note he’d taken from the statue. All that remained of his last visit to the cash machine.

The other note had already passed through many hands and was slightly limp. This was the one the waiter in Cesare’s had given him. Was this the fake banknote? And if so, had the waiter known?

Brand put the notes into his wallet. He’d go to the bank first thing tomorrow morning and find out which one was fake and which one genuine.