5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

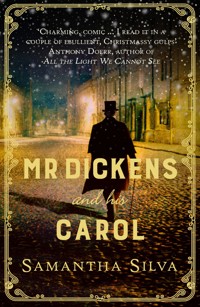

For Charles Dickens, each Christmas is been better than the last. His novels are literary blockbusters, avid fans litter the streets and he and his wife have five happy children and a sixth on the way. But when Dickens' latest book, Martin Chuzzlewit, is a flop, the glorious life threatens to collapse around him. His publishers offer an ultimatum: either he writes a Christmas book in a month, or they will call in his debts, and he could lose everything. Grudgingly, and increasingly plagued by self-doubt, Dickens meets the muse he needs in Eleanor Lovejoy. With time running out, Dickens is propelled on a Scrooge-like journey through Christmases past and present.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 358

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

By Samantha Silva

Mr Dickens and His Carol

For Atticus, Phoebe & Olive

‘Such dinings, such dancings, such conjurings, such blind-man’s-buffings, such theatre-goings, such kissings-out of old years and kissings-in of new ones, never took place in these parts before.’

– CHARLES DICKENS

Contents

Part I

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Part II

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Part III

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Author’s Note

Acknowledgements

CHAPTER ONE

On that unseasonably warm November day at One Devonshire Terrace, Christmas was not in his head at all.

His cravat was loose, top button of his waistcoat undone, study windows flung open as far as they’d go. Chestnut curls bobbed over his dark slate eyes that brightened to each word he wrote: this one, no, that one, scribble and scratch, a raised brow, a tucked chin, a guffaw. Every expression was at the ready, every limb engaged in the urgent deed. Nothing else existed. Not hunger nor thirst, not the thrumming of the household above and below – a wife about to give birth, five children already, four servants, two Newfoundlands, a Pomeranian, and the Master’s Cat, now pawing at his quill. Not time, neither past nor future, just the clear-eyed now, and words spilling out of him faster than he could think them.

The exhilaration of his night walk had led him straight to his writing chair by first morning without even his haddock and toast. He’d traversed the city twice in half his usual time, from Clerkenwell down Cheapside, across the Thames by way of Blackfriar’s Bridge, and back by Waterloo, propelled by a singular vision – the throng of devoted readers that very afternoon pressing their noses against the window of Mudie’s Booksellers, no doubt awaiting the new Chuzzlewit instalment, with its flimsy green cover, thirty-three pages of letterpress, two illustrations, various advertisements, and the latest chapter of pure delight by the ‘Inimitable Boz’ himself! Why, it was plain to him that humanity’s chief concern, now that Martin Chuzzlewit had sailed for America, was the fate of Tom Pinch and the Pecksniffs, and he considered it his sacred duty to tell them.

And so Charles Dickens didn’t hear the slap-bang of the door knocker downstairs that would alter the course of all his Christmases to come.

Like any man, he’d known a good share of knocks in his thirty-some years. Hard knocks at lesser doors, insistent rap-rap-raps on wind-bitten, rain-battered doors whose nails had lost all hope of holding. And with fame came gentler taps at better doors, pompous, pillared, and crowned thresholds in glazed indigo paint, like his own door two floors below, where the now-polite pounding was having no effect at all.

Because there are times in a man’s life when no knock on any door will divert him from the thing at hand, in particular when that thing is a goose-feather pen flying across the page, spitting ink.

CHAPTER TWO

When the fusee table clock on his desk struck three o’clock, a smallish groom (as was the fashion) with fiery red hair (as wasn’t the fashion at all) appeared at the study door with a tray of hot rolls, fancy bread, butter, and tea. Dickens dotted his final i, brandished his pages, and stood.

‘Topping! I’ve just this moment finished the new number.’

‘Wot good news, sir.’

Dickens took a roll and tore a bite out of it, his hunger returning. Everything – the whole house – seeped back into his awareness. Oh, glorious Devonshire Terrace, a house of great promise (at a great premium), undeniable situation, and excessive splendour. He was glad for the great garden outside, the clatter of crockery and clanging of tins in the kitchen downstairs, the chatter and play of his children somewhere above. And here was Topping right in front of him, vivid as ever, in his usual tie and clean shirtsleeves instead of a livery, with no sense of impropriety, and a kindly expression that asked what more he might do, because doing was what he liked best. He was the longest-lived of the household servants, and Dickens regarded him most like family of them all, something between the father he’d always wanted and the brother he wished his were.

‘Oh, Topping.’ He leant in, clutching his pages. ‘I believe I have once again . . . stumbled upon perfection.’

Topping squinched his eyes as a way of smiling without showing his teeth, which went in every direction except straight up and down. Dickens felt a great affection for him, for everyone, even the handsome house itself, which had subdued itself all day in the service of his art. He was sure he had Topping to thank for it.

A sustained holler from the bedroom upstairs announced Catherine Dickens in the full tilt of a labour of her own. The two men looked up and held their breath until it stopped. Dickens smiled with one corner of his mouth, wistful. Another child was nearly born, he knew, if stubbornly resisting its arrival into the world.

‘I suppose it altogether too much to think Catherine would hear it now,’ he said with a playful frown.

Topping’s caterpillar brows arched and fell in ironic agreement. ‘Well, sir. Masters Chapman and Hall are downstairs.’

‘Chapman and Hall, here?’ Dickens returned the half-eaten roll to the tray and trusted his pages to Topping. He sprang for the mirror to quick-comb his hair, fasten his green velvet waistcoat, and fluff his blue satin cravat. ‘Apparently even my publishers cannot wait to know what happens next!’

‘They do sit a bit on the edge of their seats, sir.’

‘Splendid. I shall read it to them!’

Topping looked at the pages, curious. ‘May I ask, does Chuzzlewit’s man Tapley have, this month, a line or two?’

‘Or three, or four.’ Dickens turned with a wink, retrieved the pages, and tapped them three times for luck. ‘I think it far and away my finest book.’

Topping blinked in solidarity and stood aside. Dickens rounded the brass ball at the banister and skittered down the stairs by twos. He had that feeling of finishing that had always been for him like floating, air under his feet and lungs like full sails. It seemed wrong to be going down when he should be soaring instead, but down he went, pages tight under his arm, edges ruffling as if with their own excitement. He thought it only his due, Chapman and Hall at his door instead of him at theirs. And so, like an actor expecting an audience squeezed into the pit and overflowing the gallery, he bounded into the drawing room to greet them, only to find the publishing partners sitting stiffly in a pair of pink parlour chairs, looking like cold fried soles.

‘Chapman! Hall!’ Dickens offered his hand as the partners stood. ‘What a surprise.’

‘I hope not an unpleasant one,’ said Hall, with his fingertips-only handshake, limp as old lettuce.

‘Certainly not.’ Dickens gave Chapman a warm double-hander. ‘Of course, normally you wouldn’t be the first to hear it, but never mind that.’

He stepped onto his favourite footstool and bowed theatrically, stirring the air with his pages. ‘Gentlemen, I give you the next instalment of everything that matters.’

‘Charles,’ interrupted Hall. ‘We’ve come on a matter of grave importance.’

Dickens peeked over his pages. Hall gripped his top hat with sharp white knuckles. Chapman mopped his beading brow.

‘In fact, we drew straws,’ said Chapman, pulling a broom bristle from his pocket.

‘His was the shorter one!’ said Hall.

Dickens looked from one to the other, confused. ‘Yet here you both are.’

A long loud shriek from above caused Hall to grimace and Chapman to sink. ‘But we’ve come at a bad time,’ said Hall.

‘Nonsense. I think you’ll find this new number strong to the very last word.’

A string of sharp yelps from upstairs punctuated their discomfort. The visitors gazed at the ceiling in horror.

‘Oh, that,’ said Dickens. ‘You mustn’t worry. The louder it is, the nearer the end.’

‘The end?’ Chapman pressed his kerchief to his lips.

‘A child!’ Dickens beamed.

Chapman and Hall looked at each other, grim. Dickens was used to the way they were – the obverse of each other in temperament and gesture, but ringers when they shared the same end. It had been Edward Chapman, short and excitable, who years before had stumbled on the notion that certain comic etchings about the exploits of Cockney sportsmen might be in want of a hack writer. But it was William Hall, tall and stern, who’d found the young Charles Dickens – court reporter, freelancer, would-be actor, and playwright – then hungry for recognition and income; in fact, any at all would do. Hall had a knack for computation.

‘Charles. I’m afraid it’s a matter of money.’

Dickens lowered his pages and stepped off the stool. If it was a matter of money, it could be one thing only. ‘My father’s been to you for a loan again, hasn’t he?’ Dickens started for the slant front desk by the window with a frustrated sigh. ‘I shall pay it at once, as always.’

‘It’s not your father this time, Charles. It’s Chuzzlewit.’

Dickens turned, his face pinched with worry. Martin Chuzzlewit had become, like so many of his characters, as good as an old family friend. He watched the partners trade glances, grave indeed.

‘It’s not selling one-fifth of Nickleby,’ said Chapman.

‘Not one-fifteenth of Twist,’ added Hall.

‘There must be some mistake.’

‘A few of the booksellers have been forced to sell at . . . a discount,’ said Chapman in a whisper, knowing the word would pierce the author’s heart.

‘A discount?’ Dickens flopped onto the giltwood settee, dangling an arm over the edge. He could swing like a pendulum, from hot to cold, light to dark. ‘It’s the name. When the name isn’t right . . . I had so many others: Sweezleback, Chuzzletoe, Chubblewig—’

‘The Americans do not like it,’ blurted Hall.

‘The name?’

‘The story.’

‘America, the republic of my imagination?’

The partners nodded as if their jaws were wired together, like puppets.

‘Where I have never shaken so many hands, been so feted and accosted for autographs, had orange peels and eggshells filched from my plate, locks of hair snipped from my head and fur from my coat?’

‘They now take you as a . . . misanthrope,’ said Hall.

Dickens pulled himself to full height. ‘I? A misanthrope?’

‘You’ve portrayed them as hypocrites, braggarts, bullies, and humbugs,’ said Chapman.

‘Humbugs?’ Dickens puffed his chest, indignant. ‘Bah!’

He drew back to wait for a retraction, or a reaction, at least. As his renown had grown, he’d learnt that a small, tactical tantrum could work wonders. Not this time. The partners were unmoved, faces expressionless. Dickens put a palm to his forehead, feeling warm and dizzy. ‘Sales are definitely down, then?’

Hall nodded to Chapman, who patted his pockets and pulled out a thin velvet box. ‘But we’ve brought you a pen.’

Dickens stared at the offering in Chapman’s hand. He could not think of a quill in the world that would ease this terrible sting. ‘At least my own countrymen do not abandon me. Why, only yesterday I saw a crush of people at Mudie’s—’

‘Waiting for the new Thackeray, no doubt,’ said Hall, doubling the blow. He took a copy of The Times from the breast of his coat and read from above the fold. ‘“Charles Dickens has risen like a rocket, but will sink . . . like . . . a . . . rock.”’

Dickens snatched the paper and read it himself, twice to be sure. ‘Well! From now on I should simply ask my public what it is they’d like to read.’

The partners seemed to admire the novelty of his thinking, but before they could say so—

‘Should Little Nell live? Sikes not kill Nancy? Should Oliver want some less?’

‘Charles,’ said Hall, retrieving the paper from Dickens’ grasp, ‘we are simply suggesting perhaps the public needs a bit of a—’

‘Christmas book!’ said Chapman, unable to contain his zeal.

‘A Christmas book? But I’m in the middle of Chuzzlewit. And Christmas is but weeks away!’

‘Not a long book,’ said Hall. ‘A short book. Why, hardly a book at all.’

‘And we’ve organised a public reading of the book on Christmas Eve!’ said Chapman.

‘A public reading of the book I have not written?’

‘We have every confidence you will,’ said Hall.

‘And have brought you a pen,’ Chapman tried again, with a toady grin.

‘We were thinking something festive,’ said Hall. ‘A bit Pickwickian, perhaps.’

‘And why not throw in a ghost for good measure?’ Chapman knocked his chubby knuckles together. ‘The public adore spirits and goblins in a good winter’s tale.’

‘A ghost?’ Dickens spluttered. ‘I am not haunted by ghosts, but by the monsters of ignorance, poverty, want! Not useless phantoms that frighten people into . . . inactivity. I do not abide such nonsense.’

‘Perhaps the ghost is wrong.’ Chapman tried the gift one last time. ‘Anyway, it is a pen.’

Dickens took the velvet box and turned it in his hand. He shook his head and thrust it back, calm in his new resolve.

‘Gentlemen. I will not write your Christmas book.’

Hall cleared his throat and withdrew a contract from a second pocket. ‘I’m afraid there’s the matter of a certain . . . clause,’ he said, opening it with a flick of his wrist. ‘To the effect that in the unlikely event of the profits of Chuzzlewit being insufficient to repay the advances already made, your publishers might, after the tenth number, deduct from your pay—’

‘Deduct from my pay?’

‘Forty pounds sterling per month.’

‘But I alone have made you wealthy men! Such a loss will ruin me.’

Hall handed him the contract, as another ear-puncturing bawl echoed through the house, shaking its walls.

‘Chuzzlewit, Charles, will ruin us all.’

CHAPTER THREE

When Catherine’s labour stalled by evening, and the doctor advised there would be no baby before morning, Dickens knew he wasn’t any use at all. Lying on the sofa did nothing to relieve his torment; a late trip to the larder for a cold lump of steak produced only indigestion and regret. He cleaned his nails and rearranged the furniture, but it didn’t help. The house had gone maddeningly quiet. It couldn’t contain his worry, and worry would do nothing to ease Catherine’s confinement or Chuzzlewit’s fate. Both now seemed fraught with danger. His brain flooded with the sort of fears night brings on: what if Catherine were lost to him, his children motherless, his work unable to save them from the maw of poverty, the poorhouse their only refuge? His nerves, one by one, prickled and popped under his skin. His legs, as they often did, twitched for elsewhere. With nothing left to do for it, he traded his writing slippers for a pair of seven-league boots and set out for his great palace of thinking – the city of London itself.

Vigorous night walks of some twenty miles were his own regular fix for a disordered mind that no amount of fighting with the bedsheets could defeat, the city’s vivid restlessness in the dark a fitting mirror for his own. From his earliest writing days, all of London had been his loyal companion and cure-all, by day and night, even in the most unforgiving weather. The city forgave. A map of it was etched on his brain, its tangle of streets and squares, alleys and mews a true atlas of his own interior. The city had made him. It knew his sharp angles, the soft pits of his being. It was a magic lantern that illuminated everything he was and feared and wished would be true. It was his imagination – its spark, fuel, and flame. From the highest Inns of Court to the lowest crumbling slums, Dickens had found his writing here, filled his mental museum with all that he’d seen and smelt, heard and felt worth keeping. But he had also found himself.

His best friend, John Forster, liked to say that his famed perambulations about the city had become a sort of royal progress, with people of all classes tipping their hats as Dickens passed. He was ubiquitous. Everyone knew his conspicuous attire; next to Count d’Orsay, he was the best-dressed dandy in London, in high satin stock, shiny frock coat, velvet collar; an excess of white cuff and rings, his waistcoats the most boldly coloured, his cravats the most brave. But it was his face, with its kind, searching eyes, variously reported in the press as chestnut brown, clear blue, not blue at all, glowing grey, grey-green, and glittering black, that drew people to him, and a smile that threw light in all directions.

Fashionable ladies stopped him in the street wanting to know, before anyone else, what plot turn was coming next. Cigar-smoking men in top hats and tails liked to think they had guessed. Omnibus drivers knew him by name; gin-shop illiterates, the piemen, even the beggars called out to ‘Boz’ cheerfully, and got a coin in return. The men who smelt of drink, Forster told him, knew him no less than those who smelt of rank.

And now he had sunk like a rock. There was no escaping it. Even the grey marbled moon low in the sky taunted him from the moment he turned out of Devonshire Terrace, no matter how fast he walked, or how far. He had stood his ground with Chapman and Hall, that was one thing. Charles Dickens could not allow himself to be pushed about by mere publishers, who were reliably first at the trough when the trough was full. But around the next corner he was bound to them, too, their futures inextricably tied.

At least he had cover of night, and a layer of smoke that washed everything in the same dull hue. He didn’t want to be seen or, worse, seen and passed by. He could hardly bear the thought that his reading public, who’d followed his career from its bright morning to its dazzling noontide, would turn away and forsake him.

Failure was not in his repertoire.

Dickens quickened his steps, counting them off in his head. He could hear himself breathe, feel his heart like a knuckle-thump in his chest. When he crossed the stinking Thames, holding his nose against the feculence that rolled up in clouds, he felt relief to leave behind the midnight world of elegant theatregoers jostling into late hansom cabs. Tonight he wanted a nether London with only poor down-and-outs to keep him company, a ragtag procession of beggars, brawlers, and drunkards whose seeming houselessness echoed some emptiness inside him.

When the last low public house turned out its lamps and the voice of a straggling potato-man trailed away, a street-sad loneliness prevailed. The air was still and heavy, not enough to flutter even a curtain at an open window. He felt himself the only person alive, as if the magic lantern had snuffed itself out, throwing his own darkness into bright relief. He didn’t know where his bleakness came from, or why, but it followed him like a shadow through the black streets of Bermondsey and Southwark, a shroud for his own low spirits. This was the land of smoke-spewing tanners and bone-boilers, sawmills and breweries. It smelt of yeast, dung, and carcasses; ash and murk pushed on his lungs, made him strain for each breath. The night was as grim as Pluto. Dickens worried the dawn might never come.

When it did, at last, he found himself in the comfort of Covent Garden, where the city sparked to something he recognised as life. An early constable surprised two street urchins sleeping in baskets and drove them away, shaking his stick. Growers’ boys stretched and yawned under wagons spilling over with cauliflowers and cabbages. Costermonger carts jingled across the piazza, tea-sellers set up tables against its pillars, itinerant dealers lined its sides. Everything was on offer: oysters, hot eels, and pea soup; gingerbread, cough drops, and pies; second-hand clothes, violins, and books; ginger beer, tea, and hot cocoa. The sellers nattered and called to each other, holding entire conversations in a single grunted syllable. Dickens stopped to take it all in and thought it as good as a party. The gentler light of day faded his low feeling and restored some mighty faith in the marvellousness of everything.

And so, rekindled by the fires of the first breakfast-men and the smell of fresh coffee and toast, he remembered there was a child about to be born, and made his way, quick-footed, for home.

CHAPTER FOUR

The coincidence of births and books in the Dickens household was by now old hat. Twelve-year-old Charley preceded publication of a three-decker Twist; Katey greeted the first monthly instalment of Nickleby, Mamie followed neatly the last. The Old Curiosity Shop was elder brother to Walter, little Frank to Barnaby Rudge. But today the five Dickens children, dressed and breakfasted by half seven, sat stairsteps on the uppermost landing, bored with books and babies both.

The mild weather was making them glum. With not a smidge of cold nor any sign of snow, Christmas seemed all but forgotten. Even the family Newfoundlands, Timberdoodle and Sniffery, and Mrs Bouncer the Pomeranian, appeared lacking in holiday cheer. There was not a holly sprig in sight, not a whiff of plum pudding, and no talk at all of the big Christmas party, which had grown in length and girth each year of their young lives. By now they should be counting the days to their father’s abracadabra conjuring spectacular, a homespun holiday theatrical, and a riotous game of blind man’s buff. Even the traditional trip to Bumble’s Toy Shop seemed on no one’s mind but theirs.

‘We must all do our headwork to solve it,’ said Katey, twirling her fat sausage curls. The charming schemer of the lot, she was dressed in plum silk to her calves, pleated, ruffled, and trimmed. Mamie, the quiet one in the pinafore, read to Walter, who rested his chin on a fist, watching Charley try to balance a marble on his shoe. Little Frank sucked on a barley candy, now and then wiping his sticky fingers on his small sailor shirt.

‘What is Christmas without Bumble’s?’ Walter traded one fist for the other.

‘I suppose Mother and Father have just forgotten, that’s all. Though I should think Mr Bumble will be sad not to see us,’ said Mamie, ever thinking of the feelings of others. Little Frank began to cry.

‘Why are you crying?’ asked Walter. ‘Crying won’t help.’

Katey sat up tall and rapped Walter lightly on the crown of the head. ‘That’s it! I’ve hit upon the very thing that will save us!’

Downstairs, just returned from his night walk, Dickens stepped inside quietly, listening for some sign of new life. Hearing nothing, he closed the front door, relieved to be on the lighter side of it. If he hadn’t eradicated Chapman and Hall from his mind altogether, at least they were tucked quietly into a far corner instead of the drawing room of his own house waiting to hold him to ransom. Yes, they had nipped at his thoughts all the way home, but only as ambient mumbling, easily ignored. Still, he pressed his forehead against the door and gave himself a good talking-to in any case, a little lecture on the importance of putting on his most inscrutable face and not blemishing the day.

‘Oh, Father,’ said Katey, swishing down the last flight of stairs. ‘It is another boy!’

Dickens turned, snapping to. ‘A boy?’

‘But we prefer girls!’ Katey fell into his arms, playing it up for sniffles and sobs. The boys rushed down behind her, crying on cue. He knew it was a conspiracy of false tears, but Dickens winked sideways to his sons and put an arm around Katey. ‘As do I, my Lucifer-Box. But never mind us.’

He wanted to leap for the stairs to greet his new son, but here were his children already born, clamouring for his attention and compelling as ever. Katey was his Lucifer-Box, the pet name he’d invented in honour of her fiery petulance. Young Charley was Flaster Floby or the Snodgering Blee. Walter was Young Skull for his fine high cheekbones. Frank was Chicken Stalker, after a comic character in The Chimes. But dear Mamie was Mild Glo’ster for her quiet, reliable nature, like the cheese. She hung back now, as she often did, searching his face for some clue to his true state of mind. She was a worrier, like he was, and could sense unease in the smallest gesture. So he gave her sudden merriment, all play. Walter wanted a magic trick. Little Frank, still sucking his barley candy, tugged on a trouser leg. Dickens hoisted him onto a shoulder, sticky fingers, sticky face, and all. Katey seized her chance.

‘Father, we were just thinking of poor Mr Bumble, who must miss us so.’

Before he could answer, Catherine’s maid, Doreen, appeared at the top of the stairs, preceded by her own heavy sigh. She was red in the face, as if her mistress’s mighty labour had been hers as well. Dickens looked up, eager for news.

‘Does she bid me come to her?’

‘This is number six, sir.’ Doreen dabbed her ruddy neck with an apron hem. ‘She bids you stay well away.’

But he couldn’t wait another second. He swung Frank down with a growling kiss on the cheek and started straight for the stairs. Walter yanked on Katey’s dress. She tried one more time, calling after him.

‘Oh, Father. Can you think of nothing to cheer us?’

But he was two flights up already, and didn’t hear her plea.

CHAPTER FIVE

Catherine Dickens, in a white satin bed gown purchased specially for this occasion, leant against a hillock of pillows, holding the newest member of their family. Dickens paused inside the door, struck by a buttery glow in the room. His wife looked weary but happy.

‘A boy?’ he whispered, tiptoeing towards them.

Catherine nodded. Dickens kissed her forehead and sat on the edge of the bed beside her. He leant on an elbow to pull aside a corner of blanket, enough to glimpse his newborn son, whose little chest rose sharp and quick, each breath a startling discovery of air. The baby had one tiny hand curled against his own pink-perfect cheek; the other clutched instinctively at his father’s ink-stained finger, seeking an anchor in the world.

‘Oh, my,’ said Dickens, overwhelmed.

‘I do hope you’ve a name in mind.’

‘Oh, Cate. Just in this moment I’ve no confidence in my naming skills whatsoever.’

‘What is it, Charley?’

Catherine was sensible to his ups and downs. She could read between the lines of his face, kept a running tally of the faintest furrows on his brow. It took some effort to mask the worry he’d walked in with. ‘Nothing,’ he lied gently. ‘I am bursting with happiness.’

Catherine looked at their son. ‘How clever he is to have come in time for the Christmas party.’

‘Christmas,’ said Dickens. ‘Yes.’ He had not the heart to tell her the Chuzzlewit news. Not now. Catherine depended on him; they relied on each other. There was a going forward about them, as if life should be an ever-expanding affair – more children, a bigger house, better things. Dickens himself was known to be quick with the sterling, and generous to a fault. Every charity and beggar in London thought him an easy mark. Catherine was fond of fine fabrics, fresh flowers in every room, and had more than once mentioned having spied a magnificent marzipan in the shape of a goose that might be the perfect centrepiece for the party this year.

‘Do you remember our first Christmas at Furnival’s Inn?’ she asked. ‘When you told me to close my eyes and declare my heart’s desire?’

Dickens did remember, in exquisite detail. How lovely his new bride was, cheeks flushed in the firelight, dark curls delighting the sides of her face, eyes sparkling with hope. His first romantic attachment to one Maria Beadnell had ended badly, but Catherine was just the remedy. The eldest daughter of an esteemed music critic, she was an unsentimental Scottish beauty whose wit and wants were a match for his own. They had begun their life together when she’d joined him at his three small rooms at Furnival’s. It was elbow-to-elbow in the early days, but they found a gladsome affection between them, a comfortable ease. Their shared memory of it was a touchstone.

‘So close them,’ said Dickens. ‘And tell me again.’

‘All right, then.’ Catherine closed her eyes. ‘I wish for a home.’

‘A home. Well wished, my dearest pig.’

‘For happiness.’

‘For what is a home without happiness?’

‘And children with which to share them.’

‘How many children?’

‘Neither too few nor too many, of course.’

‘Then just the right number.’

‘Just.’ Catherine opened her eyes to find her husband’s gaze. ‘And that every Christmas will be more splendid than the last.’

Dickens recalled those days at Furnival’s with fondness, too, how they’d lived well with less, pretending it was more. Tomorrow would make good whatever debt there was today. It had always proved true. Each Christmas had been more splendid than the last. And why shouldn’t it be so? He was Charles Dickens, after all. Catherine believed in him. Chapman and Hall thought better of the trough, perhaps, but even they would eat again.

‘Is it too much to ask for,’ she asked, ‘even now?’

‘For Mrs Charles Dickens? Whose husband is believed to have great prospects?’ He could still recite each word he’d pledged when he waltzed her about their modest rooms at Furnival’s all those years ago, giddy with thoughts of their life to come. ‘Why, we shall have such dinings, such dancings, such kissings-out of old years and kissings-in of new as have never been seen in these parts before!’

Catherine held their newborn to her cheek. ‘Oh, darling. I thought we had just the right number of children, but today I feel sure of it.’

How often he and Catherine had repeated this very scene, often in quick succession, each child greeted with trumpeting joy. Children were an act of optimism – sheer belief that the future will outshine the present. How he longed for that feeling now, the heart breaking open and flooding one’s veins with love, breaching even those banks to wash the world with it, so that every worry fell away. Everything but this.

Dickens took the swaddled child in his arms and considered his sweet-sleeping face.

‘Number six,’ he sighed. ‘I suppose we shall need a bigger house.’

With a heavy-lidded wink, Catherine patted his knee and settled back to rest. ‘Perhaps a small refurbishment will do.’

Doreen alerted them to her presence with a gravelly cough. She flung back the curtains and threw open a window. The air hung thick; dust pooled in a shaft of light. A cobweb joined the flocked fuchsia wallpaper to a yellow damask chaise. The creamy glow of the room turned to glare. Doreen took the child in her doughy arms. ‘When it’s summer for winter,’ she said, shaking her head, ‘sure enough the world’s about to go topsy-turvy.’

Dickens stood to go, kissing his wife on the top of the head.

‘I do hope the weather improves for the party,’ said Catherine, rallying long enough to suggest that if her husband had any influence in the matter of snow, he might use it now.

‘I’ll see what I can do, darling mouse.’

Catherine reached for his hand; he let his fingers twine and linger in hers. ‘We are bursting with happiness, aren’t we?’ she asked.

‘We are,’ he said, as if willing it so. He let go and turned for the door.

‘Oh, and don’t forget Bumble’s for the children, dear. They’ve been waiting for days.’

His hand gripped the knob like a vice. The mere mention of Bumble’s Toy Shop, their annual rite of merry excess, wrenched him back to the tight spot he was in. The bill would come due soon enough, and if Chapman and Hall were true to their word, sterling would be scant. But surely they were wrong. The new Chuzzlewit chapter would fix everything and all would be well with the world once again.

Books had always been the thing to save them.

CHAPTER SIX

John Forster sat behind a carved mahogany desk pulling hard on his bushy muttonchops. Dickens liked to say that the hair on his friend’s face – in the hierarchy of whiskers, somewhere between flapwings and a chin muffler – could never quite agree to meet in the middle and make a beard. It didn’t matter. Forster was thickset, pugnacious, and pompous, but the truest friend there ever was. The son of a butcher, he had long ago decided he preferred books to beef. If there were those who believed no one should be a writer who could be anything better, John Forster believed no one who could write should do anything but. He’d risen to prominence as an editor and critic, but was best known as Charles Dickens’ greatest enthusiast. He was first in line for the latest instalment on Magazine Day each month, and the last to sleep. ‘You know him?’ people in line at Mudie’s would ask. ‘Boz himself?’

‘Know him?’ Forster was known to bellow back. ‘I represent him!’

On this particular afternoon, he watched with consternation as Dickens paced back and forth in front of him like a newly caged animal.

‘Chapman and Hall have rubbed bay salt in my eyes. And on the birth of my son!’

‘A book this Christmas?’

‘Precisely.’

‘But Christmas is only weeks away. Why, it’s not humanly possible.’

Dickens stopped briefly to consider whether it was, in fact, humanly possible. ‘Well, perhaps I could do. But refuse!’

‘As you must.’

A flying rubber band stung Forster on the side of the head. It was meant to be an earnest office with only grown men in it, but here were the Dickens children in the anteroom, tending to their boredom with the amusements of rubber bands and paperweights. Forster watched Little Frank pull a linty candy from his pocket, discard a piece of gullyfluff, and stick it in his mouth.

Dickens took Forster’s grimace as a gesture of solidarity. He stopped, awaiting some further expression of indignation to match his own.

‘Why, you cannot leave Chuzzlewit stranded in America,’ said Forster.

‘My point exactly.’ Dickens slumped into a slat-back chair. ‘And yet what is the point? My public have abandoned poor Martin, and with him, me.’

‘We must not panic.’

Dickens inched to the edge of his seat, tapping the contract on Forster’s desk. ‘But what about this clause? You never mentioned any clause.’

‘I never thought they would invoke it. It’s nothing but legal mumbo jumbo.’

‘Well, they have threatened to “mumbo jumbo” me to the tune of forty pounds sterling. On a monthly basis!’

‘Preposterous! We must not succumb to this sort of blackmail.’

Dickens swayed from pique to self-pity, like the rising and falling flames of the fat office candles. ‘You are my fixer, John. What do you advise?’

Forster had been his fixer, his bulwark, bully, and protector, from the early days of Pickwick onward. When hawkers stood on street corners yelling, ‘Git yer Pickwick cigars, corduroys, figurines!’, it was Forster who’d run down the factory middlemen and demanded his friend’s fair share. The two had been ardent allies ever since, thick against the thieves of the publishing world.

Forster pawed the contract from his desk, eyes darting from clause to clause. Another rubber band struck his nose. He batted it away, impatient. ‘Besides writing the book?’

‘Yes!’

Forster sighed and tugged on his muttonchops, appraising his friend’s pleading eyes. ‘Well. I suppose you could . . . cut down.’

Dickens cocked his head as if hearing a language yet unknown to human ears. ‘Cut down?’

‘That is . . . cut back,’ said Forster, as gingerly as he could manage.

Dickens gazed at the ceiling, where his thoughts sometimes congealed. ‘Cut back,’ he said, trying out the sound of it.

CHAPTER SEVEN

Christmas had been hiding in the streets all along. The Dickens children marched behind their father in obedient single file, but their eyes were bright and round as new pennies. Shopkeepers stood on ladders, decking their windows with evergreen boughs. Old men roasted chestnuts in crowded courts; the poulterer had a hand-painted sign for his goose-and-brandy club, the butcher his roast beef, the grocer his plum pudding. Never mind the warmish weather or the clatter of carts and coaches. The air smelt like it had hailed nutmeg and snowed cinnamon.

Dickens couldn’t see or smell it. He barrelled forward like a racehorse with blinders on, head first, locked jaw and neck, crunching on his bit while rehearsing an impromptu speech about the virtues of ‘cutting back’. He was unaware that his children could barely keep up. It took them two strides for each of his, except for little Frank, who needed three in double time and a skipping step. But as they took the last corner for Bumble’s Toy Shop, there was no mistaking the elevated beating of their little hearts.

‘This must not be our usual spree, children. We are merely looking, that we may comprehend our one Christmas wish.’

‘But Katey said—’ Young Charley took a sharp elbow to the ribs.

‘Yes, of course, Father,’ said Katey as she turned to the sibling behind with a wink. ‘Merely looking. Pass it on.’

‘Because Christmas is not in the end about things, children. It is about feeling.’

‘It is about feeling, Father,’ Katey parroted. ‘Pass it on.’

Dickens was only midway through his lecture when he watched them, one by one, break ranks and rush ahead to wonder at Bumble’s famed window display, a profusion of garlands, ornaments, and fat red bows. A thousand tiny white dots had been painted around the edge of the glass, pretending to be frost. The boys admired a tinplate toy train on a track lined with painted trees. Katey imagined herself the master of a French puppet theatre. Mamie fell in love with a doll.

Dickens’ shoulders sagged. This battle would be hard won.

At the first jingle of the bell over the door announcing their arrival, the children pushed past him, scattering to every corner. Dickens froze at the threshold, gut bracing at the sight. Stacked floor to ceiling, cranny to nook, were dollhouses, drums, and music boxes, guns and swords, bows and arrows, toy soldiers, rocking horses, blocks and kites. There were toys of wax, wood, rubber, and brass; toys that rolled, toys that pushed, skipping ropes, hoops, ninepin skittles, and battledores. He had stood here a hundred times before, enchanted, but today the elaborate exhibit of childhood trappings threatened to swallow him whole.

He had a sudden urge to flee, but Bumble had spotted him, with that twinkle in his eye suggesting money and merriment would soon change hands. The Dickens children were a reliable bunch. ‘Ah, Mr Dickens!’ Bumble pranced towards him on spindly legs, spectacles bouncing on his beak-like nose. ‘Wonderful to see you!’

‘We are merely looking, Mr Bumble.’

‘Of course, Mr Dickens,’ said Bumble, with the usual fluttering and flapping about. ‘Look all you like. But how glad I am you’ve come, as I was hoping to put you down first for our Christmas fund for the Field Lane Ragged School. It is your prized position, Mr Dickens, and no one else shall have it as long as I live and breathe.’

Forster’s counsel to ‘cut down’ drummed in Dickens’ head, against all his instincts. The ragged schools had been his great cause since a visit to Field Lane when he was writing Twist showed him wretched children no charity school nor church would admit. The poor boys had no place to go and no one who’d have them, save the Fagins of the world who would use them up and toss them away like chewed-up, spat-out food scraps. What they needed was a school, and it was Dickens who’d led the charge. But he couldn’t carry it alone, not now. He tugged at his cravat, his face contorting, trying to find a way to say so.

‘I admire Field Lane, as we all do.’

‘You more than anyone,’ said Bumble.

‘Admire, and yet, sometimes it seems—’

‘That we cannot do enough. I know.’

‘Yes, but sometimes enough is—’

‘The best place to start. I quite agree.’

Dickens was never at a loss for words, words with precision and punch. But here he was, stumbling through his own thoughts, trying to find a way out. If he could not state the simple fact of being hard up for guineas, how would he ever write a book again, any book at all? Bumble seemed to take the stalling as computation. He licked the point of his pencil, ready to write any sum whatsoever, Dickens supposed, especially a big one. He couldn’t blame Bumble for expecting it. He had always given more each year than the last, where now he just hemmed and hawed.

When the bell tinkled over the door, Dickens saw his chance. ‘I shall detain you no longer, Mr Bumble. Do not miss a customer on my account.’

‘Not to worry, Mr Dickens. I shall be rid of him at once.’

Bumble flitted towards a rotund fellow with a red bulbous nose, capacious waistcoat, and a white wig perched on top of his head but not quite right. Despite his reprieve, Dickens couldn’t help listening in. ‘I shall remember,’ said Bumble, lifting his spectacles to inspect the fine print on the man’s business card: ‘Fezziwig and Cratchit.’

‘Good names!’ Dickens marched towards them, momentarily forgetting his own predicament. He plucked the card from Bumble’s hand. ‘“Fezziwig and Cratchit.” I shall put them in my mental museum.’

Glad to see his best customer’s enthusiasm waxing, Bumble cut in: ‘Mr Dickens. Let me introduce you. This is Mr . . . which one are you again?’