9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

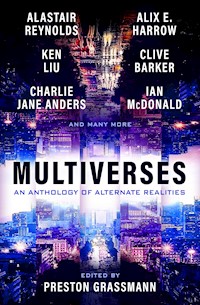

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

A mind-blowing anthology of 18 stories bringing you the infinite Earths of the multiverse.Featuring Alix E. Harrow, Clive Barker, Ken Liu, Charlie Jane Anders, Annallee Newitz, Alastair Reynolds and more.Imagine infinite Earths, an endless universe containing every possible world. What if the mistakes we make be taken back? What if the war wasn't won, or that life wasn't saved, or that heart wasn't broken?Explore the infinite potential of the multiverse with the finest minds writing in science fiction today, and see what could have been…Featuring stories from:Alix E. HarrowClive BarkerAlastair ReynoldsKen LiuCharlie Jane AndersAnnalee NewitzIan McDonaldLavie TidharJeffrey ThomasChana PorterPaul Di FilippoJayaprakash SatyamurthyEugen BaconYukimi OgawaAlvaro Zinos AmaroD. R. G. SugawaraRumi Kaneko.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Worlds in Waiting: An Introduction – Preston Grassmann

PARALLEL WORLDS

Banish – Alastair Reynolds

Cracks – Chana Porter

A Threshold Hypothesis – Jayaprakash Satyamurthy

Crunchables – Ian McDonald

Quorum’s Eye – Alvaro Zinos-Amaro

Nine Hundred Grandmothers – Paul Di Filippo

Days of Magic, Nights of War – Clive Barker

ALTERNATE HISTORIES

A Brief History of the Trans-Pacific Tunnel – Ken Liu

Thirty-six Alternate Views of Mount Fuji – Rumi Kaneko (translated by Preston Grassmann)

The Cartography of Sudden Death – Charlie Jane Anders

The Rainmaker – Lavie Tidhar

The Imminent World – D.R.G. Sugawara

FRACTURED REALITIES

#Selfcare – Annalee Newitz

A Witch’s Guide to Escape – Alix E. Harrow

Amber Too Red, Like Ember – Yukimi Ogawa

The Set – Eugen Bacon

There is a Hole, There is a Star – Jeffrey Thomas

There was a Time – Clive Barker

Acknowledgements

About the Author

ALSO BY PRESTON GRASSMANNAND AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

Out of the Ruins

Edited by

PRESTON GRASSMANN

TITAN BOOKS

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

MULTIVERSESAN ANTHOLOGY OF ALTERNATE REALITIES

Print edition ISBN: 9781803362328

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803362335

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: March 2023

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

‘Worlds in Waiting: An Introduction’ © Preston Grassmann 2023

‘Banish’ © Alastair Reynolds 2023

‘Cracks’ © Chana Porter 2023

‘A Threshold Hypothesis’ © Jayaprakash Satyamurthy 2015.

Originally published in Weird Tales of a Bangalorean. Used by permission of the author.

‘Crunchables’ © Ian McDonald 2023

‘Quorum’s Eye’ © Alvaro Zinos-Amaro 2023

‘Nine Hundred Grandmothers’ © Paul Di Filippo 2023

‘Days of Magic, Nights of War’ © Clive Barker 2004.

Originally published in Abarat: Days of Magic, Nights of War. Used by permission of the author.

‘A Brief History of the Trans-Pacific Tunnel’ © Ken Liu 2013.

Originally published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, edited by Gordon Van Gelder.

Used by permission of the author.

‘Thirty-six Alternate Views of Mount Fuji’ © Rumi Kaneko 2023

‘The Cartography of Sudden Death’ © Charlie Jane Anders 2014.

Originally published at Tor.com, edited by Patrick Nielson Hayden. Used by permission of the author.

‘The Rainmaker’ © Lavie Tidhar 2023

‘The Imminent World’ © D.R.G. Sugawara 2023

‘#Selfcare’ © Annalee Newitz 2021.

Originally published at Tor.com, edited by Lindsey Hall. Used by permission of the author.

‘A Witch’s Guide to Escape’ © Alix E. Harrow 2018. Originally published in Apex Magazine.

Used by permission of the author.

‘Amber Too Red, Like Ember’ © Yukimi Ogawa 2023

‘The Set’ © Eugen Bacon 2023

‘There is a Hole, There is a Star’ © Jeffrey Thomas 2023

‘There was a Time’ © Clive Barker 2023

Interior art © Yoshika Nagata 2023

The authors assert the moral right to be identified as the author of their work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

“The Duchess . . . was resolved to make a world of her own invention, and this world was composed of sensitive and rational self-moving matter.”Margaret Cavendish, The Blazing World

“Imagining a world creates it, if it isn’t already there.”N.K. Jemisin, The City We Became

WORLDS IN WAITING:AN INTRODUCTION

PRESTON GRASSMANN

Even within our beloved genre of science fiction, so accepting of new ideas and perspectives, there are those who prefer to set limits and guidelines, as if to protect their sacred temples from the vines of strangler trees. Fortunately, there are many more of us who turn to the genre for its inclusiveness, to celebrate the kind of diversity that foreshadows and calls into being a world of heterogeneous complexity. Nowhere is this more apparent than in our celebration of the “multiverse,” where divergence and difference are its raison d’être, and whether it’s books like Kindred by Octavia Butler, the MCU, or the diamond glare of Moorcock’s myriad suns, there is something in it for everyone.

Long before the “multiverse” became the pop-culture buzzword of modern science fiction, the notion of other universes and worlds existing in parallel with our own is as old as science itself. A third-century BCE philosopher named Chrysippus made the claim that our world was in a state of eternal regeneration, prefiguring the concept of many universes existing over time. It was part of Ancient Greek atomism, which proposed that colliding atoms could bring about an infinity of parallel worlds. However, it wasn’t until 1873 that the word itself made its first appearance in an issue of ScientificAmerican, in which William Donovan referred to it in a debate about planetary motion and God: “The Great Mechanic presides over a universe, and not merely a cohering multiverse.” Thirty years later, the word reappeared in a lecture by the philosopher-psychologist William James, who referred to the indifference of nature as “a moral multiverse… and not a moral universe.” But as with many endeavors in science, the idea of parallel worlds began in early examples of science fiction (or proto-science fiction). In The Blazing World (1666), for example, Margaret Cavendish refers to a utopian world that exists parallel to our own. In Men Like Gods (1923), H.G. Wells writes about an alternate Earth in a far-future utopia. Despite the abundance of examples in the genre, it wasn’t until the publication of Michael Moorcock’s The Blood Red Game and Sundered Worlds that the “multiverse” became a literary phenomenon. From that point on, it took root and broke through the genre like the banyan trees striving for World Tree status, extending into every part of science fiction. Although it appeared in early hard science fiction, like Isaac Asimov’s End of Eternity and Greg Egan’s Diaspora, it opened into the alternate histories of Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle and Kingsley Amis’s The Alteration. It emerges in the fantasy of the Chrestomanci series by Diana Wynne Jones and The Dark is Rising sequence by Susan Cooper. It extends outwards, giving rise to new subgenres with works like Paul Di Filippo’s The Steampunk Trilogy and William Gibson and Bruce Sterling’s The Difference Engine. Thankfully, the multiverse is worlds-wide, as broad-ranging and all-inclusive as the word itself implies.

At the very core of all science fiction is the question “what if?” What if surgical operations could be performed between one universe and another, as we see in “Banish” by Alastair Reynolds? What if we could view different versions of ourselves in others, as in “Cracks” by Chana Porter? What if a transpacific tunnel had been built after World War I, connecting the US and Japan, as in Ken Liu’s “A Brief History of the Trans-Pacific Tunnel”? The question can be asked of both the past and the future, or a present that offers a multiplicity of choices, of worlds unlike ours. It can be seen in the dream-logic reality of Yukimi Ogawa’s “Amber Too Red, Like Ember,” and Alix E. Harrow’s world of witch-librarians in “A Witch’s Guide to Escape: A Practical Compendium of Portal Fantasies.” In some form, the question is at the heart of every story in this book, and the myriad answers on offer are never short of compelling. What better way to celebrate the wide-ranging, kick-ass diversity of our genre than with an anthology of multiverse stories. If you yearn for original stories about other universes, alternate histories (and futures), and parallel worlds, then you’ve come to the right place.

If ever there was a time when we were in need of a multiverse, it’s here and now, when all the future worlds of the past have collapsed into some other timeline that some of us would rather escape from. It is with that spirit in mind, with a scope as wide as its title implies, that I’ve included a broad range of stories here, from a diverse gathering of international voices. I hope you enjoy them as much as I have.

PARALLELWORLDS

“Ghosts are, as it were, shredsand fragments of other worlds”

Fyodor Dostoevsky, Crime and Punishment

BANISH

ALASTAIR REYNOLDS

The call came in on a Monday afternoon, a little after three. Within half an hour I had reviewed my caseload for the rest of the week, spoken to my usual surgical team, bribed and arm-twisted colleagues, arranged workarounds where possible, and apologised to those patients whose procedures might need to wait until I returned. By four, I had confirmed my availability and travel arrangements were already falling into place.

I left the hospital, drove home and explained to Fabio that I had been summoned to Geneva.

Fabio watched, leaning against the doorframe, hand on hip as I threw things into a grubby plastic suitcase. I kept an overnight bag on standby but I expected to be away for at least the duration of the window.

“What’s the case?”

“A tricky one. Tumour at the base of the brain, hard to reach, and in risky territory.”

“Tiger country.”

“Exactly.” He had been living with me long enough to pick up the lingua franca of surgeons. “We need to get the tumour out without doing too much damage on the way, and make sure the margins are completely clean. Then there’s some bone under the skull that doesn’t look good on the scans, so that also needs to come out.” I paused, dithering over exactly how many pairs of underwear I really needed. “The other side are printing up a ceramic scaffold, ready for when we go in.”

Fabio nodded. “But you’ve done something similar, or they wouldn’t bring you in?”

“Three similar ones. Two went pretty well.”

“And the third?”

“A disaster.” I looked up from my packing. “That still makes me and my team about the best possible hope for this patient.”

“Isn’t there a version of your team over there?”

“Evidently not, or they wouldn’t go to this much trouble.” I shoved a ski-patterned winter jumper into the case, then took it out again. It would be much colder in Geneva than Johannesburg, but I doubted that I’d be spending much time outdoors.

“How long do you have?”

“Overnight flight, arriving early morning Tuesday. From what they’re telling us, our window stays open until somewhere between Thursday evening and Friday morning. Back by Saturday evening at the latest, I’d imagine.” I drifted to my bedside table, thinking of taking something to read. As always there was a teetering pile of prose and technical literature. I picked up the small, orange-backed collection of Christina Aroyo poetry I had been working through lately, then put it back down again. Who was I kidding? What with the medical reading I needed to do, the planning and preparation ahead of the surgery, and then the small matter of the operation itself, I’d be wiped out by the time I got back to my bed.

“You’re learning,” Fabio said, smiling as he read my thought process.

“Slowly.”

We kissed goodbye as a black Mercedes arrived outside. Bang on time. I slung my case in the back, got in, waved to Fabio as the car moved off. The driver nodded at me through the rear-view mirror, but said nothing through the glass of his Covid screen. It was a frictionless ride to the airport, traffic easy and the lights all green, allowing us to speed through intersections. Strings were being pulled at all levels, with nothing left to chance.

By the time I got to the terminal, just before six, Bruno and Fillipe were already there, bags at their feet. We greeted each other with the wariness of old friends summoned to battle, caught between the excitement of a challenge and the burden of expectation now placed upon us.

“We lose tonight travelling, and then tomorrow we have to coordinate with the local surgical teams,” Bruno said, scratching his chin with a familiar complaining look. “That’s a lot of lost time, when we’re already up against it.”

“It is not as bad as it seems,” Fillipe said, always one to look on the bright side. “We cannot go in until the scaffold is printed, and that will not be until Wednesday morning.”

I frowned. “What’s keeping them?”

Bruno shouldered his Adidas bag. “They’re a few years behind us when it comes to 3-D printing. On the plus side, we’re handling the computer design work, so that part can be done quickly.”

“You’re better briefed than me.”

He shrugged. “I read on the ride in. But don’t worry. Plenty of time to catch up on the flight.”

Half an hour later we were wheels up, all of us sitting together in a window row. As soon as the seat-belt light went off, I folded down my tray-table and powered up my Chromebook. I connected to the Swissair Wi-Fi and delved into my email. Bunching up at the top, in and around the usual admin messages, were a set of patient files, medical images and secure hyperlinks, all of them originating from a dedicated World Health Organization account.

The plane banked, golden glare from the setting sun cutting across my screen. I leaned over Bruno and tugged down the plastic window shield.

“Basal meningioma,” I said, beginning to skim through the patient notes again now that the immediate rush was over. “Man in his sixties, in otherwise good health. It’s a displacing rather than infiltrating tumour, so that’ll help with the suction. Margins should be obvious. We shouldn’t have to remove too much healthy tissue.”

“The bone is a mess,” Fillipe commented.

“Yes. Looks mushy. But there’s plenty of good bone around the bad, for anchoring the scaffold.” I used the tracker pad to zoom in on one of the scans, where a gridded pattern indicated the intended placement of the printed implant. “Do you think we might want to be a little more conservative with those margins?”

“We’ll talk it through with the other side,” Bruno said unconcernedly.

I browsed through the documents, piecing together a gradually clearer picture of the work ahead of us. I was already visualising surprises, pitfalls and the possible dodges we might use to get out of them.

“You know, this is tricky,” I said, “but I’m surprised they bounced it all the way up to World Health. It’s flattering to us that they want our expertise, but I’m surprised they felt their own teams weren’t up to the job.”

Bruno tore into a packet of salted peanuts. “Maybe they’re as behind on neurosurgery as they are on 3-D printing.”

I nodded half-heartedly, but deep down I knew it was unlikely. The worlds where we had already done remote surgery tended to be at a similar level to our own across a range of scientific, medical and engineering disciplines, rarely being more than five to ten years out of step in any one area. That was how it needed to be: what the quantum engineers called a “multiversal self-selection effect”. There were countless worlds out there with vastly different histories to our own, but unless they had been doing very similar experiments in quantum computation, with similar technical setups, the odds were against a window opening up between us and them in the first place.

I read for four hours, then spent the rest of the eleven-hour flight trying to get some sleep ahead of a full day’s work. By the time we touched down in Zurich I was in that brittle, jangling state of semi-alertness, red-eyed and overdosed on lukewarm coffee. A small executive plane took us to Geneva, where a smiling, relieved WHO delegation met us with a black limousine and a full police escort. It was mid morning on Tuesday, cold and foggy, a contrast to the last time I had been here, in the full bloom of spring. I barely had time to blink before we were driving into the sleek, glass-fronted WHO complex. There was just time to check in to our allocated rooms, have a quick shower and freshen up before we were ushered into a windowless, wood-panelled teleconferencing suite.

Coffee arrived while technicians fussed over the link to the other side. The signal was good, but it needed constant nursing. On a previous visit I’d asked if we could see the quantum computer down in the basement, the one that was whispering to its counterpart in the other version of the WHO. I was gently discouraged; apparently it looked just like any other room full of gently humming, LED-blinking cabinets, and the technicians got itchy whenever someone got too close to their baby.

Up in the conference room, on clean-scrubbed screens, surgical staff and administrators were filing into a room not dissimilar to our own, in their counterpart to the WHO. Sometimes it was called the WHO, sometimes something else, but the basics never changed. It was nearly always located in Geneva.

Introductions were made, names and faces noted, friendly professional banter exchanged. They looked just like us, down to their tired but guardedly hopeful expressions. But they were not us, nor were any of their names known to us, other than my opposite number, Beckmann. It was quite likely that they had counterparts over here who were still in medicine but who had been pulled into different disciplines, far from neurosurgery. The same would apply to our counterparts in their worldline.

“It is good of you to come at such short notice,” Beckmann told me through the screen. “We can all imagine the disruption it must cause to your schedules, as well as the time away from families.”

“If we can save a life, then it’s worth any amount of inconvenience,” I replied.

“Your expertise in this type of procedure will be invaluable.”

“It’s just luck, if you can call it that, that we’re a little further ahead of the curve in this area,” I answered diplomatically. “I’m sure, if we had time, we would find that there are many surgical approaches where you have the lead on us.”

“Time is the one thing not on our side,” Beckmann answered regretfully. “I gather you have had a chance to review our plan for the bone scaffold?”

“Yes, and it looks good.” I glanced at the WHO dossier in front of me, containing hard-copy summaries of much of the information that had already come through on my laptop, as well as a few overnight additions. “Your side kindly shared your 3-D printer software compatibility protocols with us. That allowed us to tweak the design a little on our side, just strengthening a few things here and there, and lightening where we don’t need as much density, so we can speed up the print.”

“I gather you had some concern over the margins?”

“Nothing major,” I allowed, pausing to sip at the coffee. “I always want to make sure we removed all the diseased bone, but until we’re actually in there, looking at it, we can’t be totally confident about the margins.”

“Would you like to abandon the current print, and go with a revised design, to cover a wider margin?”

I glanced at my team. The obvious answer was “yes”, because then we would be covering ourselves against any nasty surprises once we had the skull open. But restarting the design and print process now would push the actual surgery even further back. “I think we continue…” I said, mouthing a silent “for now”, just to cover myself.

“Very well then. Perhaps now we might review the remote surgical set-up?”

“No better time,” I agreed.

We abandoned our drinks and biscuits and adjourned from the conference suite into the adjoining remote surgical theatre. Screens and cameras dotted around the room meant that we could carry on the dialogue with our colleagues on the other side as they moved into their own operating theatre, the one where the actual surgery would take place. At the moment there was just a dummy on the table, but in all other respects the set-up was just as it would be on the day of the procedure, with all the necessary equipment wheeled in and all staff gowned and scrubbed in appropriately.

“If all goes well,” I said, “our only involvement will be through your screens, offering guidance when you need it.”

“But we must be ready for more than that,” Beckmann said.

So we were. If my team needed to get physical, there were two levels of engagement. The first and simplest was through robotic surgical devices that could be operated via cameras and hand controls. These hulking devices, shrouded in sterile plastic wrapping, were familiar to us all, even if there were slight differences in manufacture and function between the robots on their side and ours. Those differences were easily smoothed out by software, so that if I operated the robot in our theatre, the one in the counterpart would respond accordingly, seamlessly transferring my intentions from one worldline to the next.

If that proved insufficient – the surgery needing the precision and finesse of a surgeon’s hands – then we would go up a level, donning haptic feedback suits with full virtual-reality immersion. These would allow us to operate human-like mannequins with arms, hands and fingers. That was very much a last resort, though, because it would mean cutting Beckmann’s team entirely out of the loop, and no one wanted that. Although we would never deal with these people again after the window closed, we had a strong sense of professional empathy. I could imagine how humiliating it would feel for me if I was on the end of the same treatment.

These machines – the robots and the haptic rigs – were the reason my team had needed to fly to Geneva, rather than doing it all remotely from Joburg. The quantum computers handling the cross-talk between the two worldlines already introduced a degree of latency into the information flow. Any additional timelag on top of that built-in latency would have made the surgery far harder and far riskier. Nothing could be done about the gradual degradation in the signal, though, nor the inevitable point when the link became swamped in noise.

Chatting amiably to the other side, we completed a thorough check-out of the robots and haptics. Donning the VR goggles, each of us got the chance to feel momentarily embedded in that other worldline, just as if we had been born in it. I wondered if I was alone in feeling an urge to escape out into that curious counterpart to Geneva, to wander its streets, taste its airs and begin to gain some understanding of the altered world beyond it. Somewhere out there was almost certainly another me, another Fabio. Perhaps we had even met and fallen in love, although there was no guarantee of that.

With the theatres covered, we moved back into the conference room. There were just a few small details to be attended to. Each of us now had a separate browser running in a sandbox on our laptop. These were linked through to the WHO server connected to the basement, allowing access to the parallel internet on the other side. The purpose of this link was strictly professional: it allowed both teams to access medical databases and literature in the alternate worldline, enabling a fruitful cross-fertilisation of knowledge. There were no restrictions on the use of the browsers – the WHO treated us like adults, not children – but we were strongly discouraged from surfing the wider web. We did not need to know about the history of the other worldline, just that there was a man needing our help.

One of us had never been much good at taking encouragement, though.

* * *

Late in the afternoon, after the third meeting of the day, I found I needed some urgent fresh air. I grabbed a coffee from a machine and found my way out onto a balcony, looking out over a grey cityscape already settling into dusk. The darkening ground dropped away in leafy terraces toward the lake, for the moment mist-shrouded. Lights were coming on, inviting against the gloom. I took in invigorating breaths, pushing away the drowsiness that would probably dog me all the way back to Johannesburg.

The meetings might have been gruelling, but I could feel my confidence building. The tumour was in a difficult place, but gradually we – my team and Beckmann’s – had converged on a strategy we all liked, one that minimised the chances of wreaking too much havoc on the way. Once the tumour had been excised and pressure relieved on surrounding structures, the worst of the patient’s symptoms should start to ease. I could do nothing about post-operative complications, the long road to recovery or the chances of the cancer returning. Of the ultimate outcome, with the window long closed, we would be forever ignorant. But with the work we would do in the operating theatre, at least I could guarantee the patient the best possible odds of success.

The door slid open behind me. Bruno joined me on the balcony, elbows on the railing, saying nothing.

I waited a few moments then started to speak, about to make some observation about anaesthetic levels.

Bruno said, “It’s Banish.”

I looked at him properly. He was visibly shaken, his pallor clammy, a man in shock.

“It’s what?” I asked.

“The patient is Banish,” he stated again, speaking slowly and clearly. “He’s alive in Beckmann’s worldline.”

I shook my head slowly, wondering what had got into him. “I saw the name. I can’t even remember it now. Edward something. Edvard, maybe. It hardly matters given that we won’t be speaking to him before or after the operation. But it wasn’t Banish.”

“Banish was not his birthname. It’s a name he adopted, a nom de guerre. The real name, the one almost no one knows – except his victims and war-crimes prosecutors – that’s the one belonging to our patient.” He paused, rattled but beginning to recover his usual composure. “In Beckmann’s worldline, they don’t know about Banish. Or the war.” His eyes widened with amazement. “It just didn’t happen. Switzerland stays the same, of course – it always does. But the rest of Europe – it’s totally different. I didn’t even recognise half the names of the countries!”

I nodded slowly, believing everything he said. “There’s a reason we’re not supposed to look this stuff up. What made you do it in the first place?”

“I just wanted to know a bit more about the man we were going to save. What his life was like, what kind of person he was.” He looked down, abashed. “I shouldn’t have done it. That was mistake number one, although don’t tell me you’ve never done it. Number two was telling you. Look, I’m sorry.”

I watched city traffic for a few moments. “Maybe it’s not so bad. We all make different life choices. You say there was no war in his worldline. That means he can’t be a war criminal.”

“He isn’t,” Bruno said falteringly.

“Good.”

“But he’s not much better. He’s a politician. Populist, hardline anti-immigration, anti-democratic, you name it. Corrupt to the eyeballs, too. He’s almost as bad as the real Banish. He just didn’t get the chance to become an all-out murdering warlord.”

“Well, now at least we know why they bumped this up the chain. VIP treatment for our bad boy.”

“It’s not a joke.”

“And the crimes of his counterpart also aren’t his responsibility – or ours.”

“But he’s the same man!” Bruno pleaded. “It’s just that his life played out differently, because of other factors in his worldline.”

I tightened my fingers on the cold grey metal of the balcony railing, imagining it as a gun barrel. “We don’t get to judge him, Bruno. History’s already done that, in our worldline. That’s why Banish hanged himself, before he could go before the International Criminal Court.”

“It just seems wrong,” Bruno said. “Think of his victims, the dead and the displaced. The ones he disappeared on his rise to power. The artists and the critics he put in the ground. Did they have the benefit of a hugely expensive surgical team, beaming in from another dimension?”

“That’s the WHO’s call, not ours.”

His lips moved nearly silently. “It stinks.”

“And sometime between Thursday and Friday, we’ll lose the link with his worldline. Whatever happens in there, we’ll never hear from them again and vice versa. That box of tricks, down in the basement? The odds against it achieving another resonant lock with the same worldline are so huge, there aren’t enough zeros in the universe to calculate it. He’ll be gone, forgotten – and you and I will be knee-deep in another list of surgical cases.”

“You say it doesn’t matter?”

“I’m saying… out of sight, out of mind.”

Bruno pondered my answer. “It’s not good enough for me. I worry about what he’ll do after we take out that tumour. He’s not so old, for a politician. I used the sandbox browser to access some articles about the rise in popularity of his pro-nationalist party…” I groaned, but he carried on doggedly. “What’s to say he doesn’t start a war in his worldline in a year or two, just as bad as the one we had? Or worse?”

“Or maybe he renounces his ways and becomes a nice, caring human being.” I shrugged. “We can’t know, Bruno, and that’s why there’s no sense in worrying about it.” Before he could doubt my moral compass, I added: “I don’t like it either. There are a million people I’d sooner be treating than Banish’s slightly less evil shadow. But we’ve agreed to help Beckmann’s team with their patient, and that’s all that matters.”

He brooded. “Fillipe won’t like it.”

I thought about what I knew about Fillipe’s family, and how the war had touched them. “No, he wouldn’t. Which is as good a reason as any not to tell him.”

Bruno said nothing. To the east, even as the city fell into the night, the fog was beginning to lift from the steely shimmer of Lake Geneva.

* * *

Half an hour later I was just about keeping a lid on all-out mutiny in my surgical team. We were in my room, the three of us. I was leaning against the window, trying to keep my cool. Fillipe was practically foaming at the mouth, standing at the foot of my bed, phone clutched in his hand, looking like he was close to bludgeoning someone with it. Bruno sat on the bed, his face a mask of dejection, just about ready to crawl under the sheets.

“Just keep it down!” I implored as Fillipe’s voice broke into a shout. “We’re professionals – and sounds carry through these walls!”

“I am not lifting a finger to help that bastard. Not after what he did!”

“That’s precisely the point! The man we’re meant to be treating didn’t do any of those things!” I had to fight not to start shouting just as loudly as Fillipe. “We have to separate our thoughts about Banish from the man Beckmann has asked us to treat. They aren’t the same!”

“He has the same name, he was born in the same town, he went to the same school, he married the same woman! How much closer do you want it?”

“I am sorry,” Bruno said pitifully, for about the twentieth time. “I shouldn’t have looked.”

“I am very glad you did look!” Fillipe snapped back, also not for the first time. “Now I do not get to have to have the stain of saving him on my conscience!”