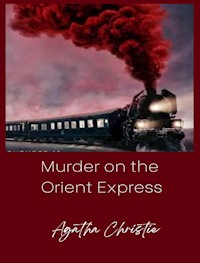

4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Planet editions

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

A luxurious journey aboard the Orient Express turns into a race against time when a murder is committed. Detective Hercule Poirot interrogates the suspects during a long stop in the mountains of Yugoslavia.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

INDEX

I - The Facts

I - An important passenger on the Taurus Express

II - Mr Bouc

III - A refusal by Poirot

IV - A cry in the night

V - Crime

VI - A woman

VII - The corpse

VIII - The abduction of little Armstrong

II - Depositions

I - The removal of conductor Michel

II - The Secretary's Testimony

III - The deposition of the waiter

IV - The deposition of the American lady

V - The deposition of Swedish Miss

VI - The deposition of the Russian princess

VII - The deposition of Count Andrenyi

VIII - The deposition of Colonel Arbuthnot

IX - Mr Hardman's testimony

X - The deposition of the Italian

XI - Miss Debenham's affidavit

XII - The deposition of the German maid

XIII - Summary of witness statements

XIV - The testimony of the weapon

XV - The testimony of baggage

III - The Meditations of Hercule Poirot

I - Which of them?

II - Questions

III - Significant Points

IV - The stain on the passport

V - Princess Dragomiroff's name

VI - Second interrogation of Colonel Arbuthnot

VII - Who Mary Debenham was

VIII - Other Revelations

IX - Poirot proposes two solutions

Agatha Christie

Murder on the Orient Express

I - The Facts

I - An important passenger on the Taurus Express

It was about 5 o'clock on a winter morning in Syria. Along the pavement

The train, pompously named Taurus Express in international railway timetables and consisting of two normal carriages, a sleeping car and a dining car with kitchenette, had already formed at Aleppo station.

Near the ladder of one of the sleeping car doors, a young French lieutenant in uniform ( ) was talking to a small man hooded up to his ears, whose only visible features were a reddened nose and the tip of an upturned moustache.

It was bitterly cold, and the task of escorting a distinguished foreigner to the station was certainly not one to be envied, but Lieutenant Dubosc carried it out with manly courage, polite words came out of his mouth in polished French, and although he knew nothing of certain events, he had heard rumours that hinted at a mysterious affair. The general - his general - seemed to be in an increasingly bad mood lately. Then the stranger from England had arrived, a Belgian by all accounts, and his arrival had been followed by a week of strange tensions in military circles. Strange things had happened: a very distinguished officer had committed suicide, another had resigned; anxious and worried faces had suddenly become more serene and certain rather strict military precautions had become less strict. As for the general, one could have said that he was suddenly ten years younger.

Dubosc had overheard part of the conversation between him and the stranger. "You have saved us, mon cher," said the general in a frail voice, his snow-white moustache quivering as he spoke. "You saved the honour of the French army, thanks to you a great bloodshed was avoided! How can I repay you?"

To these words, the stranger (his name was Hercule Poirot) had replied, among other things: "Do you think I have forgotten that you saved my life back then?". The general had then said that that episode belonged to the past, that he was not guilty of anything, and after a few more allusions to France, Belgium, fame, honour and other such things, the two had embraced each other affectionately and the conversation had ended there.

Lieutenant Dubosc still did not know what had happened; he had been assigned to accompany Poirot to the station where he was to catch the Taurus Express, and had obeyed with the eagerness and enthusiasm befitting a young officer with a promising career.

-Today is Sunday,' he said at one point. - Tomorrow night, Monday, you will be in Istanbul.

It was not the first time he said the same thing. The conversation that takes place on a platform between those who leave and those who stay is subject to a series of repetitions.

-In fact, ' agrees Mr Poirot.

-And you plan to stay there for a few days?

-Mais oui. I have never had the opportunity to visit Istanbul. It would be a real shame to go through this.... comme ça. - He snapped his fingers and made a meaningful gesture. - I'm in no hurry, I want to be a tourist for a few days.

-Ah, the Hagia Sophia Mosque, how wonderful! - Said Lieutenant Dubosc, who had never seen it before.

A sudden gust of icy wind blew around the two men, who were shivering. The lieutenant took the opportunity to glance furtively at his watch: 4.55 am. Five minutes to go. Certain that the Belgian had not noticed this manoeuvre, he hurried to find another topic so as not to interrupt the conversation.

-Few travellers at this time of year," he noted, glancing at the windows of the sleeping car.

-In fact, ' said Poirot.

-Let's hope you don' t get snowed in.

-Does this happen sometimes?

-Yes , it happened, but not yet this winter.

-Let's hope so. The weather bulletins from Europe are bad.

-Very bad. In the Balkans, for example, it has already snowed a lot and threatens to snow again.

The conversation threatened to backfire and Lieutenant Dubosc hastened to avert the danger.

-So tomorrow evening at seven forty he will be in Constantinople.

-Yes, ' said Poirot. And he added, also eager to keep the conversation going: -I have heard that the mosque of St Sophia is beautiful.

-Truly great!

Above their heads, the curtain of a window was pulled back, revealing the face of a young woman: she was looking at the canopy without lowering the glass.

Mary Debenham had hardly slept since she left Baghdad the previous Thursday. That is, she had not been able to sleep on the train that took her to Kirkuk, nor in the so-called Mosul rest home, nor last night. Tired of the enforced and nerve-wracking vigil in the compartment, however heated, that she occupied, she had pulled back the curtain to look out of the window.

It must have been Aleppo. Of course there was nothing to see but a long, dimly lit pavement. From an undefined place, an angry roar was heard in Arabic: probably an argument was going on. The two gentlemen under her window spoke French: one was a French officer, the other a small man with a huge upturned moustache. Mary smiled: she had never seen such a loaded man.

Then he saw the conductor of the sleeping car approach the two men to warn them that the train was about to leave, and heard him politely ask Monsieur to enter the compartment. The little man took off his hat.... What a strange egg-shaped bald head, thought Mary. Although plagued by serious thoughts, the girl smiled. This guy is really funny!

Lieutenant Dubosc now makes his farewell speech to Poirot. He had been preparing it in his head for some time, it was a very polished speech, very polite and appropriate to the occasion. Mr Poirot, who is not one to be defeated, responded accordingly.

-En volture, Monsieur,' repeated the host.

Mr Poirot finally boarded the train: he seemed to hesitate. The Belgian waved his hand in greeting, the Frenchman froze and returned the military salute. At that moment, with an anxious snap, the train slowly began to move.

"En fin!" murmured Mr Hercule Poirot to himself.

-Voilà , Monsieur,' said the conductor with a grand theatrical gesture, so that Poirot could see the comfort and convenience of the compartment assigned to him. Then he pointed to the neatly arranged suitcases. - The briefcase - I put it there, you see,' he added.

The outstretched hand had another meaning: Poirot understood and placed a folded banknote in it.

-Thank you very much, sir. - The conductor has become talkative and more helpful than ever. - I have tickets for the gentleman. You should also favour me with your passport.... This interrupts the journey to Istanbul, doesn't it?

-Yes . Not many travellers, apparently.

-No , monsieur, there are only two others, both English: an Indian colonel and a young woman from Baghdad. Do you need anything, monsieur?

Poirot asked for half a bottle of mineral water.

It was uncomfortable to board the train at 5 a.m., two hours before dawn; Poirot did not think he could sleep for long, huddled as he was in a corner; instead he dozed off almost immediately.

He woke up at 9.30 a.m. and went straight to the wagon restaurant for a hot cup of coffee.

At that moment only one lady was present: certainly the young Englishwoman the presenter had mentioned. She was tall, thin, brunette, in her early twenties. There was a confidence in the way she ate, in the way she called the waiter to ask for more coffee, that testified to a habit of travelling and a knowledge of the world. Hercule Poirot, who had nothing better to do, made an effort to study his travelling companion without attracting attention. He judged her to be one of those young women who can take care of themselves anywhere: She must have been cold and a little haughty. Poirot did not like the severe regularity of her features nor the delicate whiteness of her skin; he admired instead the beautiful wavy black hair and the calm, impersonal grey eyes. But she, Poirot finally decided, was a little too haughty to be called a jolie femme.

Then another traveller entered the wagon restaurant. He was a tall man, between forty and fifty, thin, tanned, his hair greying at the temples. "The Indian colonel," Poirot said to himself.

The newcomer bowed slightly to the girl.

-Good morning , Miss Debenham.

-Good morning , Colonel Arbuthnot.

-Can I ?

-Of course! Sit down.

The officer sat down, called the waiter over and ordered eggs and coffee. His gaze lingered on Hercule Poirot for a moment, then he turned away indifferently.

The two Englishmen were not very talkative; they exchanged only a few more short and trivial sentences, then the girl got up and went back to her compartment.

At breakfast, Poirot noticed that they were again sitting at the same table. They were now talking a little more animatedly. The colonel talked about the Punjab and from time to time asked the girl a few questions about Baghdad, where, he could easily understand, she had worked as a governess in some family. From the conversation that followed, Poirot realised that the two of them had discovered they had mutual friends, which immediately made them less forthcoming and, contrary to English usage, almost friends. The colonel then asked her whether she wanted to go directly to England or stay in Istanbul.

-No , I am going directly to England.

-Don't you think that's a shame?

-Two years ago I made the same trip, then with a three-day stay in Istanbul.

-I understand . Well, I confess that I am glad, because I too do not stop.

At this point, the colonel bowed a little awkwardly and blushed slightly.

He is very sensitive, our colonel,' Poirot said to himself, amused.

Miss Debenham replied that she was pleased, but in a distant tone.

Then Poirot watched as the colonel led them back into the compartment. Poirot got up, got out as well and joined them in the same carriage.

Shortly afterwards, the train crossed the beautiful Taurus landscape. The two Englishmen standing behind the window looked on in admiration. Miss Debenham suddenly sighed and Poirot heard her murmur:

-Oh , how beautiful it is here! I wish... I wish...

-How ? - asked the colonel.

-I wish I could enjoy it, this beautiful landscape! Arbuthnot took on a more determined expression and something

Then he said in a low voice: 'I wish you had nothing to do with this!

-Sst ! Pay attention, please!

-No problem,' said the colonel, looking at Poirot contritely. Then

he added: 'I don't like that I have to be a governess.

The girl laughed, a laugh that could have been described as a bit forced.

-Oh , she mustn't say such things! The trampled and harassed governess is now just a myth.

They said no more to each other. Perhaps the colonel was now ashamed of his outburst.

The train arrived in Konya at around 11.30 in the evening. The two Englishmen got off to stretch their legs and walked back and forth on the snow-covered platform. Poirot was content to observe the feverish activity at the station from the window. After about ten minutes, however, he told himself that a fresh breeze would do him good. For his part, he climbed onto the platform and strolled back and forth.

At some point he passed the tractor and heard soft voices: he immediately recognised who they were, barely visible in the shadows of a freight wagon.

-Maria . - Arbuthnot said. But the girl interrupted him.

-No , not now, not now. When it's all over. Then...

Conspicuously, Poirot turned back, rather perplexed. If he had not heard the colonel speak, he would hardly have recognised in the woman's trembling voice the confident, almost cold tone that Miss Debenham had assumed up to that moment.

The next morning he thought that the two English travellers might even quarrel. They hardly spoke to each other, and the girl looked worried and troubled: her eyes circled as if she had slept badly, her face pale and gloomy.

It was about 2.30 p.m. when the train came to an almost sudden halt. The heads of curious or restless passengers peered out of the windows. Along the tracks a small group of men could be seen talking to each other and pointing at something under the dining car. Poirot looked out in turn and asked the conductor of the passing sleeping car why. The man answered him, Poirot winced; turning around, he almost bumped into Miss Debenham; he had not realised he was behind her.

-What happened? - Miss Debenham asked in French. - Why the stop?

-Not serious, mademoiselle, something caught fire under the dining car. Meanwhile, the fire has been extinguished and the

Breakdown. Don't worry, there is no danger.

She made a gruff gesture, as if to say that the danger did not matter, and answered:

-Yes, yes, I understand: but it is the weather that worries me. We will definitely be late.

-Yes , probably,‖ agrees Poirot.

-But we must not delay! This train is due to arrive in Istanbul at 6.55pm. Then it takes another hour to cross the Bosphorus and catch the Orient Express at nine. If we were a few hours late, we would miss our connection!

-Yes , that could also happen... - said Poirot. He looked at the woman with some curiosity. The hand she held against the window trembled slightly and her lips quivered as well. - 'Is it really that important to you, mademoiselle? - she asked.

-very important. I must not miss the Orient Express for any reason. She turned her back on him and went into the corridor to join the colonel.

Arbuthnot.

However, his concern was in vain. Ten minutes later, the train set off again and arrived in Haydapassar only five minutes late; he had made up most of the time lost during the journey. The Bosphorus was rough that day and Poirot did not enjoy the short crossing. Arriving at the port of Galata, he had himself taken directly to the Tokatlian Hotel.

II - Mr Bouc

POIROT asked for a room with a bathroom and then inquired whether any mail had arrived for him. He collected three letters and a telegram. At the sight of the latter, he arched his eyebrows slightly: he had not expected this. Naturally, as usual, he opened it without too much haste and read it carefully.

UNEXPECTED DEVELOPMENTS IN THE KASSNER CASE AFTER HIS PREDICTIONS. STOP. IMMEDIATE RETURN.

-Voilà ce qui est embètant - Poirot murmured and looked around.

to the clock. He turned to the porter: - I have to leave tonight. What time does the Orient Express leave?

-Nine o'clock, sir.

-Can you reserve a seat for me in the sleeping car?

-Of course , Monsieur. At this time of year there are no difficulties: the trains are almost empty. First or second class?

-First .

-Très bien, monsieur. Where are you going?

-London .

-Then I will have a place reserved for you in the Istanbul-Calais sleeping car. Poirot returned to the office and unpacked the room he had been allocated,

Finally he entered the dining room. He was ordering from the waiter when he felt a hand on his shoulder and a voice calling behind him:

-Ah , mon vieux! This is a truly unexpected pleasure.

The man was old, short and stocky, with his hair combed back.

He smiled, evidently pleased. Poirot got up immediately.

-Monsieur Bouc!

-Mr Poirot!

Bouc, like Poirot, was Belgian and was on the board of the Wagon-Bed Company; he knew the man who had led the Belgian police for many years.

-How did you end up here? - Bouc asked warmly.

-A little business to do in Syria.

-When does it start again?

-Tonight itself.

-Excellent ! I'm going too. I'm going to Lausanne on business. Are you travelling on the Orient Express?

-Yes . -I just told the porter to reserve a place for me in the sleeping car. I was actually planning to stay here for a few days, but I received a telegram calling me to England on important business.

-Ah, business, business! - Bouc exclaimed. - Well, see you in a minute,' he concluded.

He turned away as the detective set to work on the soup, trying not to get his moustache dirty.

After tasting it, he looked around waiting for the second. There were five or six other people in the room, of whom only two interested him: two men sitting at a table not far from his own. One was a good-looking man in his thirties, no doubt American, the other - the one who had particularly caught Poirot's eye - was in his sixties or seventies. From a distance, he had the friendly appearance of a philanthropist: the slight baldness, the high forehead, the smiling mouth showing very white false teeth, everything seemed to recognise in him a man with a mild and benevolent soul. The eyes, however, suggested a very different type: small, sunken in, with a cunning and cruel look. Then, as the old man, who was saying something to his companion, looked around the room, those eyes rested on Poirot and for a split second had an expression of strange malice.

-Pay the bill, Hector,' he then said and stood up.

The voice was slightly muffled: it had a strange tone, almost sweet, but with a gentleness that would be described as dangerous.

When Poirot joined his friend Bouc in the hall, the two men were obviously on their way out; their luggage had already been brought into the hall and the young man the other had called Hector was supervising the action. Finally he opened the glass door and said to his companion: 'Now we are ready, Mr Ratchett.

The other nodded and continued.

-Eh bien, what do you think of these two gentlemen? - Poirot asked.

-They are Americans,' Bouc replied promptly. - The young man seems like a good guy...'.

-And the other?

-The other one? If I'm honest, I don't like him: he gave me an unpleasant impression. You too?

Poirot thought for a moment before answering.

-When he passed me in the restaurant, I too had a strange impression: as if a wild animal, or rather a beast, was passing by. - He spoke very calmly.

-But from the look of him one would say that he is a perfectly respectable person.

-Maybe . But I can't help thinking that the evil spirit has passed me by.

-Evil, this respectable American gentleman?

-This respectable American gentleman, indeed.

-It will be as you say! - Bouc concluded cheerfully.

-After all , there is so much evil in the world!

At that moment the goalkeeper approached. He looked confused and sad.

-This is unbelievable, sir! - called Poirot in an apologetic tone. - There is not a single free seat in first class in the sleeping car!

-Comments, ' said Bouc in amazement. - At this time of year!

But maybe there are some groups of journalists, of politicians.

-I don't know, sir,‖ the porter said respectfully and turned to him.

-But don't worry, my friend,' said Bouc, patting Poirot lightly on the shoulder. - We'll do things properly: there's always a free compartment, and it's number sixteen: the conductor won't give it to anyone. - He smiled, looked at his watch and added: - Let's go, it's time to leave.

At the station, Bouc was greeted with obsequious courtesy by the driver of the sleeping car.

-Good evening , Mr Bouc: your compartment is the one with the number one. - Then he signalled to the porters, who pushed the trolley with luggage along the carriage, which had signs saying 'Istanbul-Trieste-Calais'.

-It's all full tonight, isn't it Michel? - Bouc asked the host.

-This is incredible, Monsieur! It seems that half the world wants to leave tonight.

-However, I will have to find a place for this gentleman who is a friend of mine. Can you give him number 16?

He punctuated his request with a glance at the driver, a tall, thin, middle-aged man who smiled sympathetically but replied in an apologetic tone:

-Unfortunately, number 16 is also already occupied, sir.

-How ? What is going on here? - Bouc asked in an irritated tone. - Is there a congress? A tourist group?

-But no, a simple case, Monsieur! As I said, everyone seems to want to travel tonight.

-Turned on ! - Bouc annoyed. - Let's see: the Athens wagon will be docked in Belgrade, and also the Bucharest-Paris wagon: there will be enough space, I'd say. But we won't arrive in Belgrade until tomorrow evening.... So the

The problem is for tonight. Isn't there even a second-class bed available?

-Yes , that's true, but... - But?

-But the compartment is already occupied by a woman, a German waitress.

-Don't worry, dear friend,' Poirot interjects. - I will be able to travel in a normal car.

-Never ! - protested Bouc. Then he turned again to the train conductor: 'Tell me, Michel, have all the passengers in the sleeping car arrived?

-Not quite all of them, Mr Bouc, one is still missing,' said the landlord with some hesitation.

-And what position would you take?

-Number seven, in a second compartment. He's not here yet, and it's only four minutes to nine.

-Who is it exactly?

-An Englishman... - And Michel looked at the list in his hand. - Here, Mr Harris.

-Put monsieur's luggage in number seven,' ordered Bouc. - 'When this Mr Harris turns up, we will tell him that, given the delay, we thought he had changed his plans..... In short, we will resolve the situation one way or another.

-As you wish, Monsieur,' replied the conductor and immediately instructed the porters to take Poirot's luggage into the carriage. Then he stepped aside and ushered them into the carriage.

-In the back, Monsieur - she warned him. - The penultimate compartment. The detective walked down the corridor, but not without difficulty; most of the travellers crowded into the narrow passage, and only with difficulty did he reach the compartment indicated to him. While he was busy rearranging a suitcase, he saw the young American waiting for him at the entrance.

"Tokatlian'. When Poirot appeared, he frowned.

-Excuse me , but there must be a mistake,' he said immediately in English. Then he repeated in somewhat awkward French: - Ie crois que vous avez un erreur.

- Are you Mr Harris? - Poirot asked in turn in English.

-No , my name is MacQueen, but...

He was interrupted by the conductor's voice coming up behind Poirot: a gentle voice speaking to the American in an apologetic tone.

-I am sorry, monsieur, there are no more free beds in the carriage; this gentleman must take his seat here. - Michel then opened the window of the

In the corridor, he gets Poirot's luggage delivered by porters.

The investigator had noticed his apologetic tone and concluded that Mr MacQueen must undoubtedly have promised the conductor a good tip for leaving him alone in the compartment. There is no doubt that even the most generous tip loses value when put in relation to the wishes of a company director who is also on the train.

Michel placed the luggage on the grate, then returned to the corridor.

-Voilà , monsieur, everything is solved. Your bed is the top one, number seven. We will leave in a minute. - And he hurried away.

Poirot re-entered the compartment. His travelling companion smiled. He had evidently repressed his momentary dissatisfaction with what he undoubtedly regarded as interference and had decided to take it philosophically.

-The train is full,' he said politely.

A trilling whistle sounded, the locomotive in turn emitted a long, plaintive whistle, and a voice called out from the platform: - En volture.

The two men went out into the corridor.

-You see . - said the young American suddenly to Poirot. - If you prefer to have the bed lower because it's more comfortable and so on, go ahead; it's all the same to me, without any compliments.

A fine young man,' thought Poirot and replied:

-No , no thanks; I don't want to deprive you....

-But there is no need to talk about it!

-very cordial, but... Polite protests from both sides, then the investigator explained: -Look, it's just one night; in Belgrade...

A sudden jolt interrupted them and the two men approached the windows: the illuminated platform seemed to glide slowly along the train. The Orient Express began its three-day journey through Europe.

III - A refusal by Poirot

The next day, Hercule Poirot gets into the carriage a little late.

restaurant. He had got up early, eaten breakfast alone and spent the morning re-reading his notes on the assignment for which he had been called to England.

Mr Bouc, who was already seated at one of the tables, greeted him and motioned for him to sit down, and when Poirot joined him, he invited him to take a seat in a vacant seat opposite him. The detective sat down at the table and thus found himself in a privileged situation: Bouc was served first and both would have the best parts.

Only with cheese - a delicate and delicious cheese - did Bouc find a way to occupy himself with something other than breakfast. He was in that state of physical satisfaction that seems to predispose the mind to philosophy.

-Ah ! - he sighed. - If I at least had Balzaci's pen, I would describe this scene.... - And with a circular gesture he beckoned the round.

-It's an idea,' agrees Poirot.

-Right ? I don't think it has happened yet, yet there is the makings of a novel here. People from different social classes, different nationalities and different living conditions who have to be brought together for three days, strangers to each other.

They eat and sleep under the same roof, so to speak, without being able to stray too far from each other. And after three days they will go their separate ways and probably never see each other again.

-Also try to imagine that an accident might happen,' said Poirot.

-Ah, no, my friend...

-Of course, from his point of view, there is no hope, but let's try to think about it for a moment. For example, if all these people had in common... death.

-A little more wine? - Bouc asked, and as he poured, he spilled a drop outside. - He makes morbid talk, mon cher. Maybe it's the digestion.

-Yes , maybe so,‖ said Poirot. - The fact is that the food here in Syria is not suitable for my stomach.

He took a sip of wine, then leaned back in his chair and looked around.

At different tables sat thirteen other people who, as Mr Bouc had said, belonged to different social classes and nationalities. Poirot began to examine them one by one.

At the opposite table sat three men, probably travellers.

blocks that the confident appreciation of the waiters in the carriage restaurant had brought together. One of them was a tall, tanned Italian, who took obvious pleasure in using the toothpick; opposite him sat a thin, wiry Englishman, with an impassive and somewhat disapproving face, typical of well-bred waiters, and an American who looked like a salesman. The American and the Italian were talking, one in a high, nasal voice, the other gesticulating with a toothpick.

Poirot's gaze went further.

At a small table for two sat alone and very erect one of the ugliest women he had ever seen, but she was a distinguished and aristocratic ugliness and fascinated rather than repelled him. The lady wore a necklace of large, naturally genuine pearls around her neck and her fingers were literally covered with rings. She wore a black coat thrown carelessly over her shoulders and a tiny but very elegant cap that contrasted strangely with the toad-like face beneath. Poirot heard her speaking to the waiter in a clear, polite but unmistakably self-deprecating voice.