Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

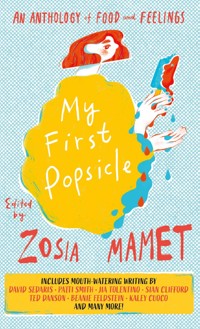

With an incredible list of celebrated contributors including DAVID SEDARIS, NAOMI FRY, PATTI SMITH, SIAN CLIFFORD and JIA TOLENTINO, My First Popsicle revels in the delights of food in all its forms. Edited by ZOSIA MAMET - Shoshanna in Girls - this is a riotous, mouth-watering celebration of jelly, mac and cheese, donuts, the best sandwich in the entire world - and much more. Of all the essentials for survival: oxygen, water, sleep and food, only food is a vast treasure trove of memory and of sensory experience. Food is a portal to culture, to times past, to disgust, to comfort, to love: no matter one's feelings about a particular dish, they are hardly ever neutral. In My First Popsicle, Zosia Mamet has curated some of the most prominent voices in art and culture to tackle the topic of food in its elegance, its profundity and its incidental charm. With contributions from David Sedaris on the joy of a hot dog, Jia Tolentino on the chicken dish she makes to escape reality, Patti Smith on memories of her mother's Poor Man's Cake, Busy Philipps on the struggle to escape the patterns of childhood favourites and more, My First Popsicle is as much an ode to food and emotion as it is to life. After all, the two are inseparable.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 369

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

v

To everyone who contributed to and made this book possible

vi

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Zosia Mamet

THERE ARE A FEW THINGS WE CAN’T LIVE WITHOUT. I mean, there are things we think we can’t live without, like coffee or sex or our favorite television show. But in terms of basic survival, the things we actually need are few in number. Water, oxygen, sleep, and food. And maybe love. But that’s if you wanna get existential about it, and I feel like we should stay literal for the time being. So, the first three things are obviously essential. But also slightly boring. Water, oxygen, sleep, sure … Food? That’s something else entirely. Food as a subject is a black hole. It is a word ripe with associations: stories, attachments, memories, disorders, emotions, hang-ups … the list is endless. My point being that at the end of the day we all have thoughts and feelings and emotions when it comes to food, certain foods more than others. But all of us, just the same. And given that food is listed as one of the few basic things we need to survive, I think we often forget how intimate our connections are to this topic. So I wanted to create a book of stories that highlighted that connection. xii

This all started a few years ago when my husband, Evan, and I went out to dinner with two friends of ours. During the meal, the wife took out her phone and said that she had to show us the cutest video. It was of their two-year-old son having a popsicle for the first time. The video was incredible. In the video, his mom hands him the popsicle and he tentatively puts it to his lips. He immediately pulls the popsicle away and starts to cry, but then a wave of curiosity washes over his face and he very slowly touches the popsicle to his lips again. There are another few moments where he looks slightly confused and is certainly debating the pros and cons of whether to venture forward or abandon the mission of this cold, sweet, alien thing. But eventually he takes the plunge and shoves the popsicle in his mouth. And then … the most epically massive smile breaks out over his face, and he starts to cackle in an infectiously giddy way. So the broken-down TV Guide version of this two-minute iPhone video is: kid eats popsicle for the first time. Sounds pretty mundane, right? But believe me when I tell you that this video was striking on so many levels. I hadn’t thought about experiencing a food for the first time in … I couldn’t even remember. Let alone having actually experienced a new food for the first time. Probably not since I was around this boy’s age. And the range of emotions that played across his face throughout this short video was exceptional. It was like watching a brilliant French mime. He hit all the big ones: fear, confusion, dislike, distaste, sadness, joy, jubilation. It was all there. And it was new. He had discovered something. I was blown away by it. And I couldn’t stop thinking about it. As we walked home from dinner, it was as if a burr had gotten stuck in my brain, scratching away at it. Food and emotions … food and emotions … the three words kept knocking about in my head like a pinball machine.

And then, over the next few days or weeks (I’m not entirely sure xiiiof the timeline here; my memory isn’t great), the topic continued to stew. I suffered from severe anorexia growing up, so I have my own history and emotionally fraught connection to food. I thought deeply about that on a personal level: my journey with it; the stories I had to tell about food, in general; specific foods, dishes, and my feelings toward them. And then, as I thought more about it, I realized how universal this topic is. No matter who you are, what your upbringing was, where you came from, your religion, your age, your profession, no matter what, we all have some form of emotional connection to food and stories to tell about it.

Once the idea had fully formed in my brain, I became convinced that this had to have been done before. Somebody had for sure already written this book. I knew I wanted it to be an anthology. I wanted to acquire as many essays from as many wonderfully different human beings as I could and hear their stories about food. I had a few to tell, but who wants to hear only from me? So I reached out to my book agents and I told them the idea. And they too thought, “This is potentially a good idea—it has to have been done before.” They did their due diligence and some deep digging to see if anything like this book existed. And hark! It did not! So in a conference room at Janklow & Nesbit on a very hot Manhattan afternoon, My First Popsicle was born.

I wrote up a little pitch/prompt to send to folks to get the creative juices flowing (please note that I will insert as many awful dad-joke food puns into this introduction as possible, so sorry not sorry). And I decided to start by dipping my toe in, or, I guess you could say, dipping my finger into the sauce? That one doesn’t quite work. Anyway, I sent it to a few friends and asked if this book was something that they might consider writing a piece for. And every person came back with a resounding yes. Then I asked two friends xivwhom I love and admire as writers. I knew I wanted the book to be comprised of some essays by professional writers, but also by humans from all walks of life, artists of all different kinds—some cooks, musicians, actors, singers—really, whoever had an interesting story to tell and would say yes to writing an essay. But I thought it wise to ask two writers first. So I did. My prompt was very loose because I wanted to give the contributors the longest leash possible and the fewest parameters to hopefully allow them to write whatever they wanted without confines. Basically, my criterion was: it needs to be about food and feelings, go. What I got back were two of the most beautiful essays I have ever read. And they were exactly what I had hoped for. Both were about food (one more than the other) and an emotional, circumstantial connection to that food or dish. And they were both wonderful, engaging, and personal stories deeply specific to the humans who had written them. And they were both vastly different. I was over the fucking moon.

And then, I got a job. My day job—acting. So that took up a bunch of time. And then a global pandemic happened, and the world shut down. And then, I don’t know, my brain broke? And for some reason, My First Popsicle got put in a drawer in the back of my mind. Until one chilly morning in January, Evan and I were having coffee in our kitchen in upstate New York, and out of nowhere he said, “Whatever happened with the cookbook?” And I didn’t really have a good response. I sat there and thought about it for a moment, and all I could say was, “I don’t know. It just kind of got put on pause.” And he said, “That was a great idea, you should pick it up again.” And so I did.

I’m sort of like a dog with a bone. When my brain hooks on, or in this case hooks back on, to an idea, I go. So I wrote to my book agents and told them I was picking Popsicle back up, and off I xvwent. Full steam ahead. I shot off emails like a chipmunk on Adderall. My agents had told me that with the two essays we already had, we’d probably want a list of ten confirmed contributors to go out and pitch the book with and a list of about twenty more that I would reach out to once we had a buyer. It took me a week. The responses to my “Hey, here’s this idea I have for a cookbook/book of essays. Wanna write a piece for it?” emails were swift in coming, and short of someone writing their own book, just having a baby, or shooting an epic film in Serbia, the responses were always a deeply excited yes. And that sealed the deal for me. These human beings who I loved and admired and revered were excited to write about this topic for my book. It felt surreal. I felt like our friend’s toddler experiencing the joy of his first popsicle.

I am still pinching myself that this book, this potluck of words from all of these exceptionally special literary cooks, has come to-gether. I am so grateful to each and every one of them for sharing their histories and stories and thoughts and feelings about food for this book. Some of these stories are raw and gut-wrenching. Some are make-your-face-hurt funny. But they are all personal and from the heart. And isn’t that when food tastes best? When it’s made with love?

I hope you enjoy reading this book as much as I have enjoyed creating it. May you relish in the words, make delicious messes attempting to cook the recipes, and feast on the beautiful images. Bon appétit.

Made with love,

xvi

CONTENT NOTE

HELLO, READER! THANK YOU FOR EMBARKING ON this literary/culinary adventure with us. We hope you enjoy every page of this book as much as we all enjoyed creating it for you.

I wanted to give you a heads-up before you venture further into these pages. I gave the contributors free rein to write about whatever they wanted as long as, at its core, their essays came back to food and feelings. Some chose to write silly essays or comedic ones or lighthearted stories. But there are also essays within the pages of this book that deal with some heavy matters.

The goal behind this book was to show that our relationship to food is varied and complicated and can span myriad emotions, and sometimes those emotions lead us to dark places. These essays are just as beautiful and important as the others, but I wanted you, reader, to know that they live here, in case the subject matter is triggering for you. xviiiThere are essays that deal with the topics of disordered eating, absent parents, death, dysfunctional families, insecurity, loneliness, self-hatred. I am not warning you about these essays so you don’t read them, but just so you know they’re there.

I would also add that I feel honored to have these pieces in the book because these are all, sadly, common issues that so many of us struggle with. Life is not perfect and it can be incredibly hard. There is no shame in having troubles or struggling. As our contributors show so beautifully in their essays, we all have something. And as someone who has struggled with many things herself—disordered eating, anxiety, depression—I encourage anyone who feels the need to seek help. Lean on those around you, reach out, use the endless resources out there. There is no shame in needing help with whatever it is you may be struggling with. And please always know, you are not alone.

MY FIRST POPSICLE

POOR MAN’S CAKE

Patti Smith

MY MOTHER HAD A WAY OF ALWAYS MAKING THINGS better. If my father was on strike at the factory and things looked exceptionally bleak, she would sing show tunes and let my siblings and me stay up late to watch monster movies on our little black-and-white TV. If the refrigerator was nearly empty, she would sit in the kitchen smoking a cigarette, thinking about how to brighten our situation. Then she would get up, flip through her recipe book, and somehow conjure the ingredients for Poor Man’s Cake, our favorite hard-times fare.

While we waited for the cake to cool, she would tell us stories of the Great Depression. She told of how families would cross the country in search of work, and how they’d pool their meager supplies and make the same cakes and wrap them in their bandannas, to be assured of something to eat in the morning.

Sometimes she would be obliged to send us off to school with nothing but a chunk of the cake, but that was fine with us. I’d tie up my chunk, a little burned around the edges with lots of raisins, 2in one of my father’s old blue paisley bandannas and imagine I was going west.

We always wondered why it was called Poor Man’s Cake. Then after my mother passed away, my sister Linda found two coffee-stained copies of the recipe. She noticed the words NO EGGS at the top of one, solving the riddle. No eggs or milk, both expensive back then, were required. Just simple ingredients, stirred with a wooden spoon and poured into a cast-iron loaf pan.

Recently, Linda made me my own Poor Man’s Cake. Breaking off a chunk, I pictured my mother in her housecoat, inevitably spattered with batter, sitting at the kitchen table pouring a cup of coffee. Linda’s cake, made with our mother’s recipe, brought back the happiest memories of the one who always found a way to laugh away tears and feed us when we were hungry.

Poor Man’s Cake

*NO EGGS*

INGREDIENTS:

2 cups sugar

2 cups raisins

2 cups water

1 cup margarine

Pinch of salt

2 teaspoons ground cloves

2 teaspoons cinnamon

3½ cups sifted all-purpose flour

Preheat the oven to 350°F.

Grease and flour a 9 x 13-inch baking dish

Place all the ingredients, aside from the flour, in a large saucepan on top of the stove.

Bring to a boil and stir.

Set aside to cool.

When cool, add the flour, stirring it in with a wooden spoon.

Pour the mixture into a greased and floured 9 × 13-inch baking dish.

Bake for about 1 hour or until a toothpick comes out clean when inserted in the middle.

SHALLOT VINAIGRETTE INSURANCE

Stephanie Danler

THE NEW YORK CITY BOXES CAME ON A MOVING truck to the cottage in Laurel Canyon. Pomelo trees scraped the roof of the truck when it turned in, so it couldn’t pull all the way into the long drive. I helped two guys from the moving company carry my stuff the rest of the way up to a shed. These boxes had been in a storage unit in the Brooklyn Navy Yard for three years, since my divorce. I felt like I had been much younger when I packed them.

The first box I opened had sweaters in it. His and mine. I remember taping up that box and thinking that we would be right back. That we were separating, dismantling our home in a cold spring, but we would be unpacking this box before the next snow came. Surveying my things in the shed, I looked at my KitchenAid stand mixer, halfheartedly protected by plastic wrap gone loose. A box of antique Bundt pans, collected at flea markets. I opened 5another box that had KITCHEN written on the side. It was full of Mason jars. Or what had been Mason jars. They were pulverized glass at this point. It hurt afresh to see it all again. To remember my ex-husband and me circling the tiny Williamsburg apartment, packing it all up, drinking iced coffee after iced coffee, not knowing how to speak to each other. I still loved him. He still loved me. We wept constantly, without ceremony, in front of the movers. They avoided us, whispering to each other in Polish. Surely, we would be coming right back to each other. It wasn’t possible that there had been many snows since then, snowstorms when I hadn’t even thought of him, or that I had moved to a place unmarked by that kind of weather.

Beyond books, most of these boxes were part of a kitchen. My marriage had revolved around food and wine. Our lives were spent in our respective restaurants where we worked the requisite twelve-hour days, and our leisure time was spent in the restaurants of our friends. I opened another box and there was my ex-husband’s bourbon collection. I laughed. Rare releases of Blanton’s and WhistlePig rye, even a bottle of Pappy Van Winkle I had scavenged for his birthday. The storage unit where they’d been residing was not climate controlled. Was the whiskey still drinkable? Yes, we had packed them like idiots full of denial. How much of our lives had we wasted in that way?

For the seven years of our relationship we were what Laurie Colwin calls “domestic sensualists.” We never ate for subsistence, only for experience. We entertained frequently and ambitiously. We made cassoulet from scratch, including grinding the meat and stuffing the sausage casings. It took weeks. Pastas were kneaded, rolled, and cut; cheeses were tempered under mesh domes; slivers of truffles 6were slid under the skin of capons. We had a culinary book collection with rare cookbooks from Kitchen Arts & Letters and Bonnie Slotnick. My ex-husband brewed beer, and each season we pickled, dropping the Mason jars into boiling water. Jars of ramps, onions, and cucumbers lined up, throwing colored light. We changed glassware as we revolved our wines, moving from stemless aperitif-style glasses to slim white-wine glasses to Burgundy bowls. After dinner we often moved the dining table to the side of the room so we could dance.

This decadence occurred in accordance with the full blooming of a zeitgeist, my ex-husband and I riding a wave that surfaced after the millennium with Anthony Bourdain, April Bloomfield, and David Chang, but one that had broken in the mid-aughts and—joyfully—kept breaking. Restaurants were New York City’s cutthroat sport. It seemed everyone was discovering the Jura wine region in France, or the salinity of Manzanilla sherry, or the pucker of fish sauce. That our passions were considered niche (at best) to the rest of the world didn’t bother us. In the city, we spoke the same language of taste. Every discretionary penny was thrown into this search for pleasure. My discovery of the food world coincided with my marriage and became inseparable. That made it seem less like a graciously prolonged moment and more like the banquet that would always be my life.

When I left our apartment in Williamsburg—and it was my first home, really—I moved into a room in a Victorian town house in Bushwick. I had only a mattress, books, and a dining table as a desk. Two suitcases of clothes. The rest of it I locked away in the storage unit. Eight other people lived in this house. I rarely saw them or even heard them. Regardless of the weather, my room had the powdery 7gray light of a storybook orphanage. I wore sandals in the shower. I could play music in my room only at certain hours. It was impossible not to feel that I had left a vibrant adulthood for an ashen version of myself at twenty-two: broke, prickly with loneliness. No belongings, no footing. The kitchen in this formerly grand town house was a playground for mice and cockroaches. Only one of the roommates ever used it. He was an Indian man, a photographer in his late forties, and he made his own Indian food every evening. The scent dominated the hallways. I could smell that his ghee was rancid, and I always wanted to say something, but I was ashamed of my snobbery. One morning there was mice shit in a line across the bottom of my bed. I didn’t trust my own authority on anything.

I stopped enjoying food. Wine felt flabby and desperate without the accompaniment. The act of changing out stemware (in an apartment with no dishwasher!) came to stand in for the fraudulence of my married life. I had become a bourgeois mannequin, had taken to caring about the wrong things. Alone again, I was safest when caring about nothing. Take-out containers piled up inside my room until I got nervous that the kitchen mice would find them. Tuna salad from a bodega, eaten with Triscuits; jars of cornichons; Greek yogurt; round after round of toast. Fried rice and steamed vegetables I could get from a Chinese place for less than ten dollars, which I could make last a week. It wasn’t just that my financial situation had drastically changed; I knew well from married life that a vat of Marcella Hazan’s minestrone could be half eaten, the other half frozen, and would be gratifying on both occasions. Cooking is nearly always the cheaper option. Yet I did not cook in that house for a year. Not even an egg. It was a form of self-recrimination. Even the thought of these once-sacred rituals made me feel empty. I had stopped believing in their power.

8Depression is always a taste to me. The tongue desiccated and parched, the oversteeped and forgotten tea, the tilting-toward-decay fizziness of sour grapes. An ambient and unspecific sense of death that keeps you from your senses. I lost food and accepted it. Though I quit cooking, I still walked to the Union Square Greenmarket in all seasons. Out of habit, I still checked out Lani’s Farm, Guy Jones, Keith’s, and still waved to the farmers I knew. On an unremarkable winter day I bought a shallot.

A smooth, lavender teardrop of a shallot.

It was a joke among my college friends that I couldn’t boil water for pasta. Maybe it was because my mother was a gifted cook who had gone to culinary school, or because we were estranged and I imagined myself nothing like her, or because I had been working in restaurants since I was fifteen years old—but I came into my twenties completely dependent on others to feed me. That changed when I moved to New York City and started serving at Union Square Cafe. But I didn’t teach myself to cook because I was inspired. I did it because I fell in love. I had just started dating my future husband and we were planning a trip to Paris. We had a lengthy list of restaurants 9to hit, but we had rented an apartment with the idea that we would also go to the markets and cook at home. The fact that neither one of us cooked did not impede this fantasy. I assumed that my general knowledge of food would translate into a virtuoso performance in the kitchen. I assumed that by buying myself The Art of Simple Food by Alice Waters, reading it cover to cover, carting it over to Paris, I would, in a small but significant way, become Alice Waters vacationing in Paris with her love. The culinary results of that Paris trip were edible but not close to transcendent. I remember reading that I should skim the fat off a beef stew and not understanding the direction. Instead I stirred as hard as I could so that fat stopped collecting on the top. I kept burying it. That, to me, was skimmed.

But one of the simpler recipes I did manage to execute in Paris was a shallot vinaigrette. While the vinaigrette came out just good enough the first time (there was too much acid to oil, but I was interested exclusively in sharp flavors back then), it was still exciting: Why would anyone buy salad dressing if they could make this? In the years to come I always had a jar of it in the fridge. It went on lettuces, on rice and farro, on steamed kale, on baked potatoes and omelets, on one hundred avocados.

In addition to a finely chopped shallot, the recipe calls for vinegar and oil. Though I prefer red wine or sherry, whatever vinegar is on hand is probably fine. I’ve also been known to add, according to mood and availability: lemon zest, anchovies, fresh thyme, chopped soft herbs like parsley or chives, fish sauce, Aleppo pepper, crème fraîche. The key to the recipe—which isn’t really a recipe as much as a gesture—is time. That means maceration. Leave the shallots and the acid alone together for an hour. The shallots will flush and plump. They will lose their rawness to the vinegar. They become their own element, not simply an accompaniment. 10

Shallot vinaigrette was the first thing I made in my transient Bushwick kitchen. It needed something to be spooned over. And so I made something to spoon it over. It did not feel like an achievement. It felt like eating, an urge temporarily satiated. But seeing the leftovers in a jar in the fridge begged me to make something else. I bought eggs and butter. I bought the good sourdough and the leftover ends of expensive cheeses: gouda, comté, triple crèmes. Dried lentils. Cans of cannellini beans, rinsed, splashed with olive oil, just heated through. I bought a head of Little Gem lettuce and a watermelon radish. Because I had the radish and the vinegar, why not do a quick pickle of it? It wasn’t exactly a triumph over dark forces: the symphony swelling, me throwing back the heavy drapes to face the sunlight. But this is how I started over. I did not have my own plates or mugs; I had my own jar of vinaigrette.

Standing in the Laurel Canyon shed with my mangled boxes, just about as far as I could get from Brooklyn, I had so much sympathy for the idiots who packed them. That sympathy made it impossible to separate my life into organized compartments—my phases, my lovers, my sublets. I don’t believe anymore that I was one person in my marriage and another when it was over, that those selves were disparate and unrepeatable. The halcyon meals of the marriage, its disappearance, and leaving New York City—it was all a wash of loss and creation. The truth is that even within that frenzy of epicurean highs, there were the seeds of our collapse. There was our penchant for drinking too much, our delirious avoidance of conflict, my fear of vulnerability, and my lust for all sorts of lives outside of matrimony. It was—much like the present moment—both paradisaical and cautionary. “The good news,” a friend said to me, “is that you 11did it once. You know you can do it again.” She meant making a home, but of course when it landed on me, it was about love. I do not live in Williamsburg or Bushwick or even Laurel Canyon anymore, but there are things from my first marriage that I’ve carried with me and have no idea what to do with. But I did cook again. I unpacked the kitchen boxes and started calling those things mine instead of ours. New beliefs emerged: A shallot vinaigrette in the fridge is insurance against hunger. There is nothing more elegant than eating leftovers with your hands. Time is the key element of any recipe. I am still learning how to skim the fat.

Shallot Vinaigrette

Finely dice some shallots.

Cover with vinegar (I prefer red wine or sherry).

Sprinkle some salt.

Leave to macerate for an hour or up to overnight.

Come back and add good olive oil (the traditional ratio is three parts oil to one part vinegar, but I usually do this to taste).

Optional: black pepper, Aleppo pepper, lemon zest, anchovies (let them macerate as well—they’ll break down), fresh thyme, chopped soft herbs like parsley or chives, fish sauce, crème fraîche.

SUMMERTIME ON LONG ISLAND

Patti LuPone

I’M LONG ISLAND BORN AND BRED. I EAT SHELLFISH, I yearn for it, I never turn it down on a menu. Every time I see steamers, or pissers, as we call them, on a menu, I order them. I had a basketful in Maine recently and they were good, but the best ones come from my beloved Northport Bay.

They say you can take the kid out of Northport Bay and Long Island Sound, but you can’t take the bay waters and all its succulent treasures out of the kid.

As children, we’d wait for low tide—that distinct, overpowering scent of life and death, muddy waters with creatures just below the surface but at the shoreline—ah!

Steamers, littlenecks, cherrystones, mussels, all for the scraping and picking.

Once, I ate a bushelful of raw littlenecks. Had my knife, pried the delectables open, and scarfed the clams down. 13

My dad belonged to the Kiwanis Club, and they would have clambakes at Crab Meadow Beach. I will always treasure the memory of those days and nights: the deep hole, dug in the early morning; the fire and coals; the seaweed; the crustaceans, the corn, and the potatoes all steamed to perfection; and we still hunted at the water’s edge because it was fun!

Any crab, shrimp, clam, or lobster takes me home to summertime on Long Island.

14

Russell’s Linguine con Vongole

30 littleneck clams

Scrub the outside of the shells, then put the clams into a bowl filled with cold water and lots of salt to clean the sand out, and put the bowl in the fridge for a few hours.

IN PREPARATION TO COOK:

Place into a large sauté pan (with a cover):

Olive oil—enough to cover about half the pan

Anchovy paste—about a 3-inch length of paste from the tube

Red pepper flakes—about 1 teaspoon

Fresh garlic—6 large cloves, thinly sliced

WHEN READY TO COOK:

Turn on heat to medium under the pan, then stir until all the ingredients meld together and become fragrant.

Add clams and cover.

Check after about 5 minutes, shaking the pan back and forth a bit to help the clams open.

Once the clams are all open, remove from the heat—it’s done.

Pour over buttered linguine cooked al dente.

Sprinkle with finely chopped fresh Italian parsley.

Salt to taste, if needed!

Toss and enjoy!

BALL BUSTER

Andrew Bevan

HOW WAS I MEANT TO KNOW THAT THE MOMENT I took a giant bite of that meatball, my entire world would crash down?

It was a midweek Valentine’s Day evening. I was in my mid-twenties. My boyfriend and I sat at an intimate, cash-only Italian boîte called Max on Avenue B and East Fourth Street, a place the Times had rubber-stamped as serving well-prepared food with warmth. It was the perfect low-key, low-pressure, unpretentious, romantic neighborhood spot to celebrate a low-key, low-pressure, unpretentious, romantic relationship. After years of chasing the proverbial golden ring of trendy New York hotspots and the aloof throngs of cool urbanites that inhabited them, tonight felt comforting and beautifully habitual.

I had a history of throwing myself at dudes where the only prerequisites were that they occasionally held a guitar or a skateboard and were as unemployed as they were emotionally unavailable. Set up by my co-worker three years prior, this was the sanest 16and sincerest partnership I’d ever experienced. As a whole, it felt like a significant change of habit from the flash-in-the-pan novelty of my past dalliances. My first blissfully regular, real, and reliable adult union. While my boyfriend did exhibit the ideal mussed brown locks of a skater dude, he called and showed up when he said he would. He was polite, measured, contemplative, and complimentary. He loved his family and had good but not stuffy taste. I was seduced by his functionality and the functionality of this relationship.

There was an old charm and coziness to the restaurant with its reclaimed wood and Edison bulb accents that were light-years ahead of this now particularly ubiquitous Mumford & Sons design crutch. My boyfriend and I sat across from each other, tightly flanked by two straight couples. On my left was an older turtlenecked married pair who looked like they were in a high-end optical ad. On my right was an overly touchy thirtysomething duo. She clutched a bodega bouquet of two dozen roses with baby’s breath. They were clearly just hitting their three-month mark.

New Yorkers must develop tunnel vision when dining at the city’s many cramped restaurants, lest the chatter, compelling (good and bad) sartorial choices, or PDA of our table neighbors prove too distracting. Worse is the accidental eye contact that leads to a perfunctory “How are the mussels?”—breaking the fourth wall to the point of no return. Your two-top is now a four-top and you’re on a double date with strangers. The next thing you know, you’re looking at pictures of their three-legged schnauzer and debating whether long-sleeved wedding dresses are evergreen.

As a friendly gay man, whether I’m feeling chatty or not, I somehow either instigate or attract these impromptu conversations. It’s a blessing and a curse: it’s part of what makes this town 17and being a friendly gay man so great. Yet at times it’s essential to keep things one-on-one—especially when your partner is shy and slightly socially awkward, as my boyfriend was.

That Valentine’s Day, we were hyperfocused on not breaking the imaginary barrier while we ate our beet and burrata salad with pistachio vinaigrette and toasted garlic bread topped with anchovies—the latter of which he flicked onto my plate before taking a bite. He liked anchovies but knew I loved them more.

We talked about a movie we wanted to see and how his photo shoot that day had ended early instead of late, which never happens. Despite working under one of the best fashion photographers of our time and having his own successful solo career, he had an almost sheepish schoolboy charisma. A year or so before we met, he had lost forty pounds and was now certifiably hot—and it was the holy grail of hot because he didn’t love himself enough yet to be narcissistic or egomaniacal. He was a genuinely great guy with a great head of hair (predating the man-bun mania-turned-punch-line), a great heart, and a great career. With him, there was no smoke and mirrors and no gimmicks. He was husband material, the type of man I wanted to marry and then argue with about banal things like him forgetting to buy toothpaste at the store (or, worse, buying the expensive, natural, clay-tasting herbal kind) and be secretly annoyed but charmed that he always said “What’s doing?” instead of “What’s up?”

Our overzealous waiter set down my entrée—a heaping bed of spaghetti covered by a blanket of marinara and topped with extra-large meatballs—with a certain over-Coca-Cola’d (or more likely, cocained) franticness. He seemed desperate for me to take it off his hands. I was happy to oblige.

As a big-city transplant from Colorado, comfort food always 18seems to take on a lot of meaning. I once dated a twenty-six-year-old who invited me over to his apartment for the first time for dinner and a movie. “His apartment” ended up being his childhood home, and his nanny served us her famous homemade tomato soup and grilled cheese as we watched The Ring. With each bite, my shock and awe for a grown-ass man still shamelessly relying on his nanny for supper melted into a euphoric sense of nostalgia and adolescence.

Having the latest food trends and an encyclopedia of far-flung cuisines at our fingertips at any given time (Sri Lankan food at one a.m., quail egg and sea urchin as menu mainstays, waffles sold out of trucks) is part of what sets Manhattan apart. But sometimes you just need something ordinary and straightforward, like spaghetti and meatballs, to amplify your peaks and console your valleys. The culinary equivalent of watching When Harry Met Sally for the twenty-eighth time, comfort food grounds you in your happy place, returning you to a simpler, wholesome time, if even just for a moment—a hug in a bite.

“How’s the gnocchi?” I asked my boyfriend as I confidently tornado-twisted the pasta onto my fork. I halved one of the enormous meat spheres and popped it into my mouth, a move that was both plucky and presumptuous. I noticed him becoming nervous and visibly shifty, like that kid in the spelling-bee finals too old to be wearing overalls. The gnocchi must be too dry or the Gorgonzola too strong, I thought. Maybe I should give him some of mine.

He swigged some water, and then … he said … it.

“I don’t think I can be in a relationship right now,” he muttered in the casual tone usually reserved for commentary like “I don’t know if it’s going to be cold enough to wear my new coat tomorrow” or “I wonder if the tiramisu here is homemade or frozen.” 19(For the record, I’d order it either way. Any tiramisu is better than no tiramisu.)

So there we sat, wading in our own existential reduction sauce. Was this unrehearsed or premeditated? Trapped on a rustic banquette (in an act of passive-aggressive chivalry, I always offer my dining companion the booth side of the table and then resent them for accepting the gesture), he avoided eye contact. How could he lull me to this place with this sense of homey security only to drop a bomb? A place where the stakes felt so low only a few moments ago. This is not where you break up with someone. This isn’t even where you have business discussions or talk about a family will (and even if it were, might I remind you again that it’s fucking Valentine’s Day). This is a place where the menu is written on chalkboards and they pour molten cheese on top of juicy, sweaty meat orbs. The upcycled and lived-in wooden school chair beneath me and the lone antique lightbulb that swayed ever so slightly above lost their quaintness and suddenly felt hard and cold—fit for a time-out corner or a cinder-block Law & Order interrogation room.

I wanted to say “Fuck you, you just gave me your anchovies, you little bitch!” but instead I stared in disbelief with a mouth full of a gargantuan ball of meat. I demanded some sort of eye contact, but his pupils were playing a nervous game of Frogger. Curiously, his kind eyes had not instantly turned to dead pools of ink.

Despite being a shamelessly reactionary and emotional person, when the bottom is truly pulled out from under me, I become stupefied and confounded to the point of paralytic shock. The little red string connectors and microchips in my brain seem to melt into a pudding. I freeze, waiting for someone to hit my reset button. 20

Once I deciphered that what he was saying was actually what he was saying, I realized I essentially had two options:

Immediately spit out the ball in a napkin or, better yet, on his face. How great that meat-and-tomato bloodshed would be with ball guts dripping down his puppy-dog cheeks and onto his gray boiled cashmere sweater.Masticate the colossal mass of red meat to completion, which would lead to, I’d say, an awkward pause of about thirteen to sixteen seconds. Ample time for me to gain sustenance for battle.The meatball was delicious and really the only thing working in my favor at this traumatic moment in my life, despite the fact that it now seemed entirely too inelegant and vulnerable to eat during what was becoming “the last supper.” My keen foresight also told me I probably would be too scarred in the future to ever return to this now-tainted establishment, let alone consume a meatball again. There could be some sort of sense memory reminder of him and this night anytime I encountered one for the rest of my life. I did not want to be left with meatball PTSD in perpetuity. I love meatballs. I mean, I really love meatballs. So I decided to take the bold step of savoring the bite for a full NINETEEN seconds.

I made a conscious effort to deeply relish that meatball as if it were my death-row meal, taking any solace I suddenly had left in this world from the savory consolation prize of marinara and meat in my mouth. He stared timidly at his plate while strategically moving his food around it. Maybe he was thinking how he’d just 21ruined gnocchi for himself for years to come. Regardless, he still looked like that spelling-bee kid, but one who was getting scolded by his helicopter parents for accidentally mumbling a swear word after misspelling eudaemonic in the final round. Like the time I was sent to the principal’s office for yelling “FUCK LIKE A DUCK” after losing a fourth-grade field-day race.

I finished my last chew and swallowed gingerly with an almost ladylike finesse. This was obviously to offset the giant, unapologetic bite I had been working on, or rather, through.

Truth be told, I have a history of biting off more than I can chew, figuratively and quite literally. I’m not a delicate eater, which makes me often fit right in at a Denver barbecue but stick out at the Condé Nast cafeteria or, say, um, a Met Gala or a Chanel dinner. That’s not to say I like a mess. I practically came out of the womb in a complete Ralph Lauren look and extra-stiff Bass saddle shoes, and I’ve always made my bed every day. And though I love kids, I often wince at sticky babies drenched in chocolate ice cream or tomato sauce while others continue to assure me how utterly adorable they are.

I’ve been told since I was probably seventeen that I resemble Ira Glass or Stephen Fry. Though I can now respect both men and also my own face, they’re not ideal aesthetic comparisons you want to hear as a teenager starting to creep out of the closet. I’ve always had a long face, a commanding forehead (that I aptly cover with bangs), a strong chin, two sleepy, contemplative little eyes, and a slight, almost Bernadette Peters–like pout (despite always yearning for a sizable Calista Flockhart or Julia Roberts trap).

While my giant glasses and overly astute visual awareness always 22