11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

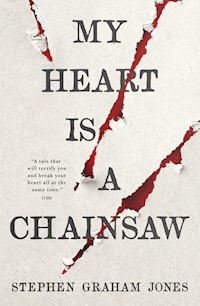

A gripping, bloody tribute to classic slasher cinema, final girls and our buried ghosts, combining Friday the 13th, the uncanny mastery of Shirley Jackson, and the razor wit of the Evil Dead. The Jordan Peele of horror fiction turns his eye to classic slasher films: Jade is one class away from graduating high-school, but that's one class she keeps failing local history. Dragged down by her past, her father and being an outsider, she's composing her epic essay series to save her high-school diploma. Jade's topic? The unifying theory of slasher films. In her rapidly gentrifying rural lake town, Jade sees the pattern in recent events that only her encyclopedic knowledge of horror cinema could have prepared her for. And with the arrival of the Final Girl, Letha Mondragon, she's convinced an irreversible sequence of events has been set into motion. As tourists start to go missing, and the tension grows between her community and the celebrity newcomers building their mansions the other side of the Indian Lake, Jade prepares for the killer to rise. She dives deep into the town's history, the tragic deaths than occurred at camp years ago, the missing tourists no one is even sure exist, and the murders starting to happen, searching for the answer. As the small and peaceful town heads towards catastrophe, it all must come to a head on 4th July, when the town all gathers on the water, where luxury yachts compete with canoes and inflatables, and the final showdown between rich and poor, past and present, townsfolk and celebrities slasher and Final Girl.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 624

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Also by Stephen Graham Jones and available from Titan Books

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Night School

Just Before Dawn

Slaughter High

The Initiation

Graduation Day

Curtains

Silent Rage

Don’t Go in the Woods

Happy Birthday to Me

Visiting Hours

Stage Fright

Don’t Go in the House

Final Exam

Hell Night

The Final Chapter

Acknowledgments

“At once an homage to the horror genre and a searing indictment of the brutal legacy of Indigenous genocide in America, Stephen Graham Jones’ My Heart Is a Chainsaw delivers both dazzling thrills and visceral commentary … Jones takes grief, gentrification and abuse to task in a tale that will terrify you and break your heart all at the same time.”—TIME Magazine

“He’s a master of that creepy, anxious feeling … It’s wickedly suspenseful and incredibly clever.”—Tor.com

“Horror fans [will] be blown away by this audacious extravaganza.”— Publishers Weekly starred review

“Meticulously crafted horror [with a] vivid, moving, gory end ... This extraordinary novel is an essential purchase.”—Library Journal starred review

“Every detail both entertains and matters. Brilliantly crafted, heartbreakingly beautiful.”—Booklist starred review

“A homage to slasher films that also manages to defy and transcend genre. You don’t have to be a slasher fan to read My Heart is a Chainsaw, but I guarantee that you will be after you read it.”—Alma Katsu, author of The Deep and The Hunger

“Brutal, beautiful, and unforgettable. It’s everything I never knew I needed in a horror novel.”—Gwendolyn Kiste, Bram Stoker Award-winning author of The Rust Maidens

“A frantic, gory whodunnit mystery, with an ending both savage and shocking. Don’t say I didn’t warn you!”—Christopher Golden, New York Times-bestselling author of Ararat and Red Hands

“An easy contender for Best of the Year. It left me stunned and applauding.”—Brian Keene, World Horror Convention Grandmaster Award-winning author of The Rising and The Damned Highway

Also by Stephen Graham Jones and available from Titan Books

THE ONLY GOOD INDIANS

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

My Heart is a Chainsaw

Print edition ISBN: 9781789098099

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789098105

Published By Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition: September 2021

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Copyright © 2021 Stephen Graham Jones

The right of Stephen Graham Jones to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

To Debra Hill: thank you, from all of us.

The slasher film lies by and large beyond the purview of the respectable

—Carol J. Clover

NIGHT SCHOOL

On the battered paper map that’s carried the two of them across they’re not sure how many of the American states now, this is Proofrock, Idaho, and the dark body of water before them is Indian Lake, and it kind of goes forever out into the night.

“Does that mean there’s Indians in the lake, or does it mean that Indians made it?” Lotte asks, a gleam of excitement to her eyes.

“Everything here’s named after Indians,” Sven says back, whispering because there’s something solemn about being awake when everyone’s asleep.

Their rental car is ticking down behind them from the six-hour push from Casper, the doors open because they just wanted to look, to see, to soak all this in before going back to the Netherlands at the end of the week.

Lotte shines her phone’s light down onto the fluttering map and looks up from it and across the water, like trying to connect what she’s seeing in lines and grids to what she’s actually standing in.

“Wat?” Sven says.

“In American,” Lotte tells him for the two-hundredth time. If they want partial course credit for immersion, they have to actually immerse.

“What?” Sven repeats, the word belligerent in English, like trying to make elbow room for itself.

“That should be the national forest on the other side,” Lotte says, chinning across the water because her hands are struggling to get the map shut.

“Everything’s a national forest,” Sven grumbles, angling his head as if to peer deeper into the darkness at all these black trees.

“But you can’t do that in the king’s forest, can you?” Lotte asks, finally getting the map folded in one of the six different ways it’s possible to fold it.

Sven follows her eyes across Indian Lake. There’s little floating pinpoints of light over there that only really come into focus when you look into the darkness right beside them.

“Hunh,” he says, Lotte coming up behind him to rest her chin on his shoulder, hold his waist in her hands.

Sven breathes in deep with wonder when the lights rearrange themselves, suggesting great yellow necks in the inky blackness: strange and massive animals, piecing the world together one lakeshore at a time. Then, a ways down the shore, a ball of flickering light arcs up into the velvety sky and hangs, hangs.

“Mooi,” Lotte says right next to his ear, and Sven repeats it in American: “Beautiful.”

“We shouldn’t,” Lotte says, which of course means the exact opposite.

Sven looks back to the car, shrugs sure, what the hell. It’s not like they’re going to be here again, right? It’s not like they’re going to get another chance to be twenty years old in America, a whole lake at their feet like it bubbled up just for them to dip their toes into—and maybe more.

They leave their clothes on the hood, the antenna, draped over the open doors.

The mountain air is crisp and thin, their skin pale and bare.

“The water will be—” Sven starts to say, but Lotte finishes for him, “Perfect,” and with that they’re running the way naked barefoot people do across gravel, which is delicately, hugging themselves against the chill but laughing too, just to be doing this.

Behind them Proofrock, Idaho, is dark. Before them a long wooden pier is reaching out over the water, pointing them across the lake.

To get their nerve up for how cold this is going to be, once their feet find those wooden planks, Lotte and Sven stretch out and really run, not worried about the chance of nails or splinters or falling. Sven howls up into the vast open space all around them and Lotte snaps a blurry picture of him with her phone.

“You brought that?” he says, turning around to jog backwards.

“Document, document,” she says, her arms drawn in like a boxer’s now that Sven’s looking back.

He raises an imaginary camera, takes his own picture of her.

Lotte is looking past him now, though, her eyes not as sure as they just were, her strides shortening, slowing, her hands and elbows going into strategic-coverage mode.

There’s a much closer light flickering at what’s got to be the end of the pier, and it looks for all the world like a fisherman in dark rain gear, holding an old-style lantern up at face level. No, not a fisherman: a lighthouse keeper who hasn’t seen another soul for three years. A lighthouse keeper who thinks that holding his lantern close to his own eyes will improve his vision.

And then the light’s gone.

Sven’s hand finds Lotte’s and they slow to a shuffle, the sky yawning empty and deep above them. All around them.

“Wat?” Lotte says.

“In American,” Sven chides, forcing his smile.

“I don’t anymore think we should—” Lotte starts, but doesn’t finish because Sven, walking now instead of running, is jumping on his left foot, his right splintered or nailed or stubbed, something sudden and unpleasant.

The light at the end of the pier comes on, curious.

“Look,” Lotte says to Sven.

When he stops hopping and grabbing at the sole of his foot, the light goes back off.

He nods, getting it, then stomps his hurt right foot down with authority.

The light glows on.

“Try it,” he says to Lotte.

Hesitant, she does, stomping, getting no response. But then she jumps with both feet, comes down hard enough to jangle whatever bad connection is happening down there.

“Gloeilamp isn’t screwed enough,” Sven diagnoses, pulling her ahead.

“Screwed in enough,” Lotte fixes, traipsing behind.

When they get there, step into that puddle of wavering light, Sven licks the pads of his fingers and reaches up under the rusty cowl to tighten the bulb, the light losing its thready flicker immediately, shining an unwavering cone of warmth down onto their pale thighs now, their shadows stark behind them, bleeding off into the darkness.

“We’re gonna fix this place up right,” Sven says, meaning all of America.

Lotte darts in to kiss him on the cheek, then, her eyes locked on Sven’s the whole while, and still holding his fingertips until she can’t, she steps over the end of the pier as easy as anything.

Sven turns his head against the splash, smiling and cringing both, but the splash doesn’t come.

“Lotte?” he says, stepping forward, shielding his face from the water he knows has to be coming.

She’s in a dark green canoe that’s rocking back and forth— she must have spotted it while he was fiddling with the lightbulb. Sven raises his hands, snaps another make-believe picture of her, says, “Cover up, this one’s for the grandchildrens. I want them to see how amazing their grootmoeder was when I first was knowing her.”

Lotte purses her lips, unable to hide her smile, and Sven steps down with her, arms wide so as not to roll them.

“This isn’t stealing,” he says, reaching up to unhook the canoe’s rope. “It was just floating here—out there, I mean. We had to swim out even to get it, to save it.”

“We’re gonna fix this place up!” Lotte says as loud as she can around Sven, leaning on the shaky little left-behind cooler to push them away from the pier. She trails her hands in the water and, drifting out from the pier now, can just see their rental car. It looks like a laundry bomb exploded over it. No: it looks like two kids from the Netherlands fizzed away from pure joy, disappeared into nothing, leaving only their clothes behind.

“What?” Sven asks in perfect American.

“We don’t have a paddle,” Lotte says. It’s the funniest thing in the world to her. It’s making this little expedition even more perfect.

“Or pants, or shirts . . .” Sven adds, taking both sides of the canoe and rocking it back and forth.

“Koude,” Lotte agrees, hugging herself. Then, like a dare, “Warmer in the water.”

“Out where it’s diepere,” Sven says, correcting himself before she can: “Deeper.”

They reach over to paddle with their hands, the water bitter cold, and after about twenty yards of this Sven liberates the white lid off the little cooler. It’s a much better paddle than their hands, and—importantly—it doesn’t care about freezing.

“My hero,” Lotte says in precise English, pressing herself into his back.

“It can be warmer up here too,” Sven says, but doesn’t stop drawing them farther out onto the lake.

Lotte presses the side of her face into his back, her new vantage point giving her an angle into the now-open tiny cooler.

“Hey!” she says, and extracts a clear baggie with a sandwich inside, its peanut butter smearing.

“Ew, pindakaas,” Sven says, and pulls deep with the cooler lid, surging them ahead.

Lotte unceremoniously shakes the sandwich out into the water without touching it, crosses her finger over her lips so Sven will know not to tell on her about this, then drops her phone into the baggie and neatly seals the top, blowing into it at the very end so the phone is in a make-do balloon.

“Your ziplock tas can also be a flotatie device,” she says in her best KLM flight attendant voice.

Sven chuckles, says, “Flotation.”

The phone in the bag is still recording. Lotte angles it away from her, holds it up so it can see ahead of them.

“What do you think they are?” Sven asks, nodding to the lights they don’t seem to be any closer to yet.

“Giant fireflies,” Lotte says with a secret thrill. “American fireflies.”

“Mastodons met—with bioluminescente tusks,” Sven says.

“Air jellyfish,” Lotte says, quieter, like a prayer.

“Isn’t there a tree fungus that’s fosforescerend?” Sven asks. “Being serious, nu.”

“Now,” Lotte corrects, still using her wispy-dreamy voice. “It’s the Indians. They’re painting their faces and their bodies for revolt.”

“Until John Wayne Gacy hears about it,” Sven says with enough confidence that Lotte has to giggle.

“It’s just John Wa—” she starts, doesn’t finish because Sven is jerking back from leaning over the side of the canoe, jerking back and pulling his hands up fast, something long stringing from them. He stands shaking it off, trying to, and the canoe overbalances, starts to roll. Instead of letting it, he dives off the other side, his Netherbits mostly hidden from the phone’s hungry eye.

He slips in almost without a sound, just one gulp and gone.

Alone on the canoe now, Lotte stands unsteadily, the back of her hand coming instantly up to her nose, her mouth—the smell from whatever stringy grossness Sven dragged in over the side.

She dry heaves, falls to her knees from it.

They’ve drifted into . . . what? A mat of algae? Lake scum? At this altitude, snow still in the ditches?

“Sven!” she calls to the blackness encroaching from all sides now.

She covers herself with her arms, sits on her heels as best she can.

No Sven.

And now she knows what that smell has to be: fish guts. Some men from the town gutted a big haul of them over the side of their boat, the intestines and non-meaty parts adhering together with the congealing blood to make a gooey floating scab.

She coughs again, has to close her eyes to keep from throwing up.

Or maybe it wasn’t a whole net of fish—they can’t do that here in inland America, can they?—but one or two of the really big fish, pulled up from the very bottom of the lake. Sturgeon, pike, catfish?

Sven will know. His uncle is a fisherman.

“Sven!” she calls again, not liking this game.

Not necessarily in response to her call, probably more to do with his lung capacity, Sven surfaces maybe twenty feet to Lotte’s left.

“Gevonden—got it!” he’s yelling.

What he’s waving over his head is the bright white lid of the little cooler.

“Come back!” Lotte calls to him. “I don’t want to see the giant fireflies anymore!”

“Mastodons!” Sven yells back, clapping the lid on the water, the sound almost unbearably loud to Lotte, like drawing attention they don’t want. She looks to the lights on the far shore to see if they’re all turning this way.

She gathers her phone-balloon, shakes the camera so it’s facing her, and says into it in perfect English, “I hate you, Sven. I’m cold and scared and when you’re asking yourself what you did wrong, why you didn’t get any in the big state of Idaho, you can play this and you can know.”

Then she wedges the phone backwards half under the canoe’s bow deck, up against the stem—the pointy hidden corner at the front where you can stuff a ziplock baggie you’ve blown up and hidden a phone inside.

“Come to me!” Sven says. “I don’t want to touch that . . . that hair again!”

“It’s not hair!” Lotte calls back. “It’s fish gut—”

What stops her from finishing is the distinct sense that someone was just standing behind her. Which would be impossible, of course, since behind her there’s only the lake. Still, she whips around to the other end of the boat, certain there was a shadow there, just in her peripheral vision, already gone.

“It is kelp?” Sven’s asking now. “Is that how you say it in Engels?”

“English,” Lotte corrects, losing patience with this.

“Fuck English!” Sven says back. “Het is haar!”

It’s not hair, though.

If it were hair, that would mean that . . . Lotte doesn’t know: would it mean that a moose or a bear or a cowboy horse had died out here, or floated out here while dead and bloated, then burst in the heat of the day, geysering blood and gore up in a chunky fountain?

The canoe thunking into something where there should be nothing tells her that’s just what it has to be.

She shrieks, can feel sudden tears on her face, her breath the kind of deep she’s about to lose control of.

“Sven!” she screams, holding hard to the side of the canoe, and now, instead of another thunk, what she hears, fast like little footsteps, is a series of . . . not quite splashes, but some disturbance on the surface of the water. Fish in a line, jumping? A formation of bats snatching insects from the top of the lake? A rock someone skipped in the daytime, still making it across to the other shore?

She pushes away from whatever it is.

“Sven, Sven, Sven!” she’s saying, less loud each time, because it feels like her voice is putting a bullseye on her back.

They never should have come to America. This isn’t some big adventure.

Lotte looks back to the pier, to the light she knows is real, and right when she looks is when it blinks off then on again—no, no, it didn’t go off, something passed between her and it.

Seconds later, a profanely intimate sound squelches across the water to the canoe, like a wet ripping. From where Sven was? Is she even still in the same place in relation to him?

Lotte stands, feels more exposed than she ever has, even though she can’t see her own arms.

She falls back, almost over the side, when Sven starts screaming. In Dutch, in English, in human, except more primal— the way you only ever scream once, Lotte knows.

All Lotte can make out is “Wat is er mis met haar mond?” before his voice gargles down, stops abruptly.

Lotte reaches in to paddle back, away, she’s sorry, Sven, she’s sorry, she’s sorry to America too, they shouldn’t have violated her at night, they should have driven all the way around Idaho, she’ll tell everybody, she’ll warn them all away if she can just—

Her arm is up to the elbow in the mat of hair and rot and guts, it’s stringing off her, draping into the canoe, wrapping around her but she doesn’t care, she’s lying on her stomach now to pull harder for the shore, her fingertips pushing down to where the water’s even colder.

Once, twice, twenty times, and then—her hand connects with something solid? Her head is instantly filled with the slow-motion image of a dead horse floating underwater, the pads of her fingers brushing the white diamond between its eyes, her lightest touch pushing the huge dead body drifting down even deeper.

She pulls back, sits up holding her hand to herself like it’s injured, and then what she touched with that hand bobs past.

The white cooler lid, streaked red.

Lotte shakes her head no, no, no, and then, because what else can she do, she rolls over the other side of the canoe, fights through the tendrils of decay, some even going in her mouth, trying to reach down her throat, and then she’s to open water, swimming hard for the dim lights of Proofrock like only an elementary school swim-meet veteran can.

The phone she left behind in its foggy balloon is just recording the empty aluminum canoe now, and one blurry corner of the little cooler. But it’s listening in its muted way.

What it hears is the front part of Lotte’s scream.

She doesn’t get to finish it.

JUST BEFORE DAWN

Jade Daniels slouches—that’s the only word for it—into the staging area for Terra Nova on a twelve-degree night on the thirteenth of March, the Friday before spring break officially gets going for Proofrock.

In the left pocket of her thin custodian coveralls is a box-cutter, what her dad would probably call a “shitrock” knife, and in her right is her fist. Under her overalls there’s just a girl-cut Misfits t-shirt, probably technically too small if that matters, and her threadbare jeans, most of the holes in the thighs not from washing dishes at the pancake house or moving boxes in a shipping warehouse—Proofrock isn’t big enough for either of those places—but from scraping at the fabric with her fingernails during seventh period, her state history class, which she calls Brainwashing 101. Her fingernails are black, of course, and her hair is supposed to be green, that was the plan one hundred percent, it was going to look killer, but Indian hair doesn’t take the dye like the box says “all hair” should, so she’s got a bobbed orange mop to deal with, which was what started the fight at her house thirty minutes ago, spitting her up here.

If her dad had just been able to watch her cross from the front door to the hall without saying anything, she’d probably be in her bedroom right now, headphones clamped on, a bootleg slasher crackling on the screen of her thirteen-inch television set with the built-in VCR.

Her dad can never keep his mouth shut, though, especially six beers into a night that’s probably going to take a whole case to get through.

“You got to stop eating so many carrots, girl,” he said with a halfway chuckle, punctuating it with a drink from his bottle.

Jade stopped like she had to, like she guesses he must have wanted her to.

His name, Tab Daniels, is the one he earned in high school, because he threaded fishing line back and forth across the headliner glued to the roof of his Grand Prix, festooned it with fishing hooks, and then proceeded to hang enough pull tabs onto those barbed hooks that the headliner finally collapsed onto him one seventy-mile-per-hour night.

The wreck should have killed him, Jade knows. Or wishes. She was already on the way by then, so it’s not like it would have blipped her out of existence. All it would have blipped her to would be a less crappy version of her life, one where she lives with her mother, not her so-called father.

But of course, because she’s doomed to grow up in the same house with her own personal boogeyman, the wreck just broke his bones, Freddy’d his face up, because, as he always tells anybody who doesn’t know to have already left the room, God smiles on drunks and Indians.

Jade would humbly disagree with that statement, being half as Indian as her dad and getting zero smiles from Above, pretty much. Case in point: her dad’s drinking buddy Rexall chuckling about her dad’s orange-hair joke, and tipping his chin up to Jade: “Hey, I got a carrot she can—”

Hating herself for it the whole while, Jade had actually bared her teeth at this, expecting her dad to backhand Rexall, living reject that he is. Or if not backhand him, at least give him an elbow in warning. At the very very least Tab Daniels could have whispered not so loud to his high school bud. Wait till she’s gone, man. Anything would have been enough.

He’d just chuckled in drunk appreciation, though.

Maybe if Jade’s mom were still in the picture, then she could have thrown that maternal elbow, glared that glare, but whatever. Kimmy Daniels’s place is only three-quarters of a mile away from Jade’s living room, but that might as well be another galaxy. One not in Tab Daniels’s orbit anymore—which is exactly the idea, Jade knows.

She also knows that stopping in the living room like she did was a mistake. She should have just kept booking, pushed on, shouldered through the smoke and the jokes, landed in her bedroom. Once you’re stopped, though, then starting again without a comeback, that’s admitting defeat.

She fixed Rexall in her glare.

“My dad was saying that about eating carrots because girls who want to be skinny try to eat only carrots, and the whites of their eyes will sometimes go orange, from overdoing it,” she said, touching her hair to make the connection for Rexall. “I’m guessing you being such a shit-eater explains the color of your eyes?”

Rexall surged up at this, clattering empties off the coffee table, but Jade’s dad, his eyes never leaving Jade, did hold Rexall back this time.

Rexall’s name is because he used to deal, back in whatever his day was, and Jade’s pretty sure it was exactly that: one single day.

Jade’s dad chewed the inside of his cheek in that gross way he always does, that makes Jade see the knot of spongy scar tissue between his molars.

“Got her mother’s mouth,” he said to Rexall.

“If only,” Rexall said back, and Jade had to blur her eyes to try to erase this from her head.

“That’s right, just—” she started, not even sure where she was going with this, but didn’t get to finish anyway because Tab was standing, stepping calmly across the coffee table, his eyes locked on Jade’s the whole way.

“Try me,” Jade said to him, her heart a quivering bowstring, her feet not giving an inch, even from the oily harshness of his breath, the ick of his body heat.

“This were two hundred years ago . . .” he said, not having to finish it because it was the same stupid thing he was always going on about: how he was born too late, how this age, this era, he wasn’t built for it, he was a throwback, he would have been perfect back in the day, would have single-handedly scalped every settler who tried to push a plow through the dirt, or build a barn, tie a bonnet, whatever.

Yeah.

More like he’d have been Fort Indian #1, always hanging around the gate for the next drink.

“Might have to take you over my knee anyway,” he added, and this time, instead of continuing with this verbal sparring match, Jade’s right fist was already coming up all on its own, her feet set like she needed them to be, her torso rotating, shoulder locked, all of it, her unathletic, untrained body swinging for the fences.

It should have worked, too. Tab’s head was turned for the last drink in his bottle, and she’d never tried anything like this before, so he wasn’t special on-guard. He had been getting suckerpunched his whole stupid life, though, and had some radar as a result. Either that or God really was smiling on him.

Him, not his daughter.

He caught her fist in his open left hand easy as anything, pulled her face right to his, said, “You do not want to do this with me, girl.”

“Not with,” Jade said right into his lips, “to,” bringing her knee up into his balls like there was a rocket in her boot heel, and then, in the time it took him to keel over into the coffee table, clattering empty bottles away, Jade was running through the screen door, exploding out into the night, never mind that she wasn’t dressed for it.

The only reason she got her work coveralls at all was that they were hanging on the laundry line, skinned with frost—nobody expected weather to have rolled in over the pass like it had. She didn’t put the coveralls on until the end of the block, though, and when she did she was watching the street the whole time, her eyes the only heat she had anymore.

“Alice,” she says to herself now, shuffling through the open gate of the staging area for the Terra Nova construction going on twenty-four/seven across the lake.

Alice, the final girl from Friday the 13th, has sort-of orange hair, doesn’t she?

She does, Jade decides with a cruel smile, and that makes this dye-job not a disaster, but providence, fate. Homage. This is Friday the 13th, after all, the holiest of the holies. But she’s pissed, she reminds herself. There’s no smiling when you’re the kind of pissed she is. All that’s left to do now is turn up somewhere with hypothermia. What she’ll tell Sheriff Hardy is that her dad was partying like always and kicked her out just like last time.

All Jade has to do is tough it out. Go past shivering to something more blue-lipped and dry-eyed. Her loose plan had been to walk down the town pier to get that done—it’s public, it’s dramatic, somebody’ll find her before she’s all the way dead—but then she’d seen the flickering glow from the staging area, had no choice but to moth over.

The flickering glow is a fire, it turns out. Not a bonfire, but . . . she has to smile when she gets what she’s seeing: the grunts on the night shift have used the front-end loader to scoop up all the wood and trash from around the site, probably their last task before clocking out, and then they left all that trash in the big steel bucket, kept it lifted a foot or so off the ground, and dropped a flame in, probably on a shop towel they held on to until the last finger-burning instant.

Burning’s one way to get rid of a load of trash, Jade supposes. With Proofrock trying to dip down into single digits, maybe it’s the best way.

What gives Jade license to come right up to the fire with the rest of the grunts, by her reasoning at least, are her work coveralls, grimy from afternoons and weekends mopping floors and emptying trash and scrubbing toilets. Her name—“JD” for “Jennifer Daniels”— sewn onto her chest in cursive thread proves she’s like them: not important enough to bother remembering, but the front office has to have something to call you when there’s a spill needs taken care of.

“Howdy,” she says all around, trying for no lingering eye-contact, no extra attention drawn to her. She immediately regrets howdy, is certain they’re going to take that as insult, but it’s too late to reel it back in now, isn’t it?

The one with the yellow aviators—shooting glasses, right?— nods once, leans over to spit into the fire.

The guy beside him with the mismatched gloves backhands Shooting Glasses in rebuke, nodding to Jade like can’t Shooting Glasses see there’s a lady among them?

To show it’s no big deal, Jade leans over into the heat, her frozen face crackling, and spits all she can muster down into the swirling flames, her eyelashes curling back from the heat, it feels like.

The grunt with his faded green Carhartts tucked into his cowboy boots chuckles once in appreciation.

Jade wipes her lips with the back of her bare hand, can feel neither her lips nor the skin of her hand, is just using the brief action to case the place.

It looks the same from inside as it does through the ten-foot chain link: pallets and pallets of building material, ditch witches and scissor lifts, tired forklifts and crusty cement chutes, trucks parked wherever they were when dusk sifted in, brought the real chill with it. The heavy equipment like the front-end loaders and the bulldozers are all herded onto this side of the fenced-in area, the silhouette of the backhoe rising behind like a long-necked sauropod, the crane the undeniable king of them all, its feet planted halfway between this fire and the barge that ferries all this equipment back and forth across Indian Lake.

The day that barge was delivered by a convoy of semis and then assembled on-site, just before Thanksgiving break, it had been enough of an event that a lot of the elementary school classes took a field trip to watch. And ever since that day, Proofrock hasn’t been able to look away. It never seems like that long, flat non-boat can carry one of these ten-ton tractors, but each time it just squats down in the water like it thinks it can, it thinks it can, and then, somehow, it does. Watching through the window during seventh period, Jade hates the way her heart swells, seeing the monstrous backhoe balanced on the nearly-submerged back of the barge again.

Does she want the backhoe to slide off, plummet down to Drown Town under the lake, or does she want the water to just rise and rise around its tall tires, nobody noticing until it’s too late?

Either will do.

At the other end of that ferry trip is Terra Nova, which Jade despises just on principle. Terra Nova is the rich development going up across the lake, in what used to be national forest before some fancy legal maneuvers carved a lip of it out for what the newspapers are calling the most gated community in all of Idaho— “So exclusive there aren’t even roads around to it!” If you want to get there, you either go by boat, balloon, or you swim, and balloons fare poorly with mountain winds, and the water’s just shy of freezing most of the year, so.

What “Terra Nova” means, all the articles are proud to reveal, is “New World.” What one of the incoming residents said, kind of famously, was that when there are no more frontiers, you have to make them yourself, don’t you?

Right now there’s ten mansions going up over there at a pace so breakneck it looks almost like the houses are rising in time lapse.

What those entrepreneurs and moguls and magnates probably don’t know, though, is that if you walk the shore around to the east from Proofrock to Terra Nova, having to tippy-toe along the dam’s spine at a certain point, the one clearing you’ll stumble into will be the old summer camp, long gone to seed: nine falling-down cabins against a chalky white bluff, one chapel with open sides so it’s pretty much just a low roof on pillars, like a church that’s sinking, and a central meeting house nobody’s met at since forever. Unless you count the ghosts of all the kids murdered on those grounds fifty years ago.

To everyone in Proofrock it’s “Camp Blood.” Give Terra Nova a summer or two, Jade figures, and Camp Blood will be the Camp Blood Golf Course, each fairway named after one of the cabins.

It’s sacrilege, she tells anyone who’ll listen, which is mostly just Mr. Holmes, her state history teacher. You don’t remake The Exorcist, you don’t sequel Rosemary’s Baby, and you don’t be disrespectful about soil an actual slasher has walked across. Some things you just don’t touch. Not that anybody in town cares. Or: everybody likes the fifteen dollars an hour Terra Nova’s smooth-talking liaisons are paying anybody who wants to hire on for the day. Anybody like, say, Tab Daniels. Thus the surge of beer he’s been riding the last couple of months.

The transaction’s not what they think, though, that’s the thing. They’re not selling their time, their labor, their sweat, they’re selling Proofrock. Once Camelot starts sparkling right across Indian Lake, nothing’s ever going to be the same—this rant courtesy of Mr. Holmes. Before, all the swayed-in fences and cars with mismatched fenders on this side of the lake were just the way it was, the way it had always been. Now, with Terra Nova’s Porsches and Aston Martins and Maseratis and Range Rovers rolling through to park at the pier, Proofrock’s cars are going to start seeming like a rolling salvage yard. When people in Proofrock can direct their binoculars across the water to see how the rich and famous live, that’s only going to make them suddenly aware of how they’re not living, with their swayed-in fences, their roofs that should have been re-shingled two winters ago, their packed-dirt driveways, their last decade’s hemlines and shoulder pads, because fashion takes a while to make the climb to eight thousand feet.

As Mr. Holmes put it on one of his sad digressions—it’s his last semester before retirement—Terra Nova wants to make the other side of the lake pretty and serene, nice and pristine. It’s not quite so concerned about Proofrock, which before long is going to be just what gets left behind on the way to something better: cigarettes ground out under boot heels, quick pisses behind tires as tall as a house, little jigs and jags of angle iron pushed into the dirt along with layer after sedimentary layer of lonely washers and snapped-off bolts, which is why no way will Jade be staying here even one more minute than she has to after graduation. That’s a promise. There’s Idaho City, there’s Boise, there’s the whole rest of the world waiting for her. Anywhere but here.

But that, like the hypothermia, is all later.

Right now it’s just rubbing her hands together over the fire, never mind the sparks swirling up. If she flinches from them, she’s a girl, she won’t deserve to be here at this hour.

“You all right there?” Shooting Glasses asks.

“Excellent,” Jade says back, giving him a sliver of a grin. “You?”

Instead of answering, Shooting Glasses tries to make subtle eye contact with the other grunts, except quarters are too close for “subtle.”

“I interrupting something?” Jade says all around.

Mismatched Gloves shrugs, which means yes.

“Feel like I just barged into a wake, I mean,” Jade says, going from face to face.

“Good call,” Cowboy Boots says while wiping at his nose.

“I’m not Catholic,” Jade says, pulling back with all of them from a long swirling exhalation of sparks, “but isn’t there usually more drinking at a wake?”

“You’re thinking Irish,” Mismatched Gloves says with a sort-of grin.

“Let me guess,” Jade says. “Your name . . . McAllen? McWhorter? Mc-something?”

“That’s Scottish,” Shooting Glasses says, staring into the fire. “Irish is O’Shaunessy, O’Brien—think luck O’ the Irish, that’s how I remember it.”

“Which of them has leprechauns?” Cowboy Boots asks.

“Shh, shh, you’re Indian, man,” Shooting Glasses tells him. “We’re talking Europe stuff here, yeah?”

“Me too,” Jade says.

“You’re a leprechaun?” Mismatched Gloves asks, smiling now as well.

“Indian,” Jade says, and, by way of formal introduction to Cowboy Boots, “Blackfoot, my dad tells me.”

“Isn’t that Blackfeet?” Shooting Glasses asks.

“Montana or Canada?” Mismatched Gloves adds in.

Jade doesn’t tell them that, in elementary, until she caught the Montana return address on what turned out to be a Christmas check, she’d always thought she was Shoshone, because those were the Indians her social studies class said were in Idaho. So, being in Idaho, that’s what she must be. But then that return address, and that tribal seal by the address—she’d saved it, kept it hidden alongside her Candyman tape. Too, back in those days she’d had the idea that, since she was starting out half Indian, that as she got bigger and taller—got more and more physical actual blood—someday she’d be full-blood like her dad.

“Blackfeet,” she says back with faked authority. “What the fuck do you think I said?”

“Yeah,” Mismatched Gloves says, holding his different-colored hands high and away, not touching this anymore, “she sounds Blackfeet all right.”

“Adopted,” Cowboy Boots says about himself, by way of introduction. “Could be anything.”

“What he’s saying is he’s a mutt,” Mismatched Gloves says.

“Mutt your ass,” Cowboy Boots says back, and Jade files that away: on this job-site, “your ass” is the add-on way of turning anything around. Her kind of place.

“So who died?” she says to whoever’s answering.

“He didn’t die,” Cowboy Boots says, blinking something away.

“Depends on what you consider dead,” Mismatched Gloves adds.

“Greyson Brust,” Shooting Glasses says, being respectful with the name.

“Hired on with us,” Mismatched Gloves tells Jade, then shrugs an exaggerated shrug, like trying not to think of something.

“Zero days since the last accident?” Jade asks, aware of the eggshells she’s walked onto here.

Shooting Glasses chuckles kind of humorlessly.

“Place is cursed,” Jade says, which gets all of their attention, a few more unsubtle glances among them. “Probably, I mean,” she adds.

“So where you headed?” Cowboy Boots asks, trying to get Jade’s eventual exit started.

Jade, not a poker player, accidentally sneaks a glance in the direction of the great void in the night Indian Lake is, shrugs.

“She’s not going to,” Mismatched Gloves says, watching Jade hard. “She’s going from, right?”

“Killer name,” she says back to him, the answer to a question he hadn’t even been asking a little.

“Say what?” Cowboy Boots says.

“Greyson Brust,” Jade says, obviously. “That’s—he sounds like horror royalty, I mean. You can hear it, can’t you? ‘Greyson Brust’ is right up there with Harry Warden, with Billy Loomis, with John Wakefield, with Victor Crowley and Sammi Curr. With . . . I’m gonna say it . . . Jason Voorhees. Some names just have that killer ring, don’t they?”

“You good, there?” Mismatched Gloves asks, and Jade looks down to where he means: the red blooming slow in the left pocket of her coveralls, from when she was flicking the utility knife’s razor blade open and shut against her leg on the walk here.

“Got some red on me, yeah,” she kind-of-quotes, shrugging his inspection off, all the tiny scars up and down her thighs and hips crawling over themselves to be seen. And then, because now nobody’s saying anything and everything’s awkward and starting to suck, Jade backs up a smidge from the fire, says, “But you’re right, yeah. I have to be careful here. Shouldn’t be standing so close to open flames like these, I mean.”

“You were—” Cowboy Boots starts, then tries again: “I thought you were talking about—”

“Slashers,” Jade says with her best evil grin. “I was talking about slashers. They’re why I can’t catch fire here. I’m a janitor, I mean, a custodian, and what’s that but a caretaker, right? I’m practically Proofrock’s caretaker when I’m wearing this. And if I stand too close, catch a sleeve on fire, and the rest of me goes up, then . . .”

Jade has to gulp her smile down.

“I’m talking about Cropsy,” she says, looking from face to face for even a hint of recognition. “Slashers from 1981, Alex.”

“Um,” Shooting Glasses says.

“Okay, okay,” she says, backing up in her head to figure out where to start for them. “Say you’re the main and only caretaker for Camp Blackfoot. The one from The Burning, I mean. Not the one from Camp Blood, which is a movie to them, a place to us around here, but forget that for now. It’s just—it’s the same way Higgins Haven is in both Friday the 13th Part III and Twisted Nightmare, right?”

“You’re the janitor for this camp,” Cowboy Boots fills in, playing along.

“If I’m Cropsy I am, yeah,” Jade says, ignoring everything else. “And I’ve got my own cabin and everything. But these kids, these punks, they don’t really appreciate the way I’ve been ‘taking care’ of things, so much. Remember, this is sleepaway camp. It’s its own little closed system of punishment and reward.”

“Think I know that camp,” Shooting Glasses says.

“You went to camp?” Mismatched Gloves says.

“I know the punishment part, I mean,” Shooting Glasses says back to him.

“So I’m Cropsy, I’m the janitor, the caretaker,” Jade goes on, before they forget they’re listening to her. “It’s my job to clean up all the blood in the showers. It’s my job to tump the cut-off fingers out of the bottom of the canoe. Any deaths by wasp-nest or arrow or axe, I clean them up just the same. But then all these kids get it in their head that I need to be taught a lesson, so they elect to play a harmless little prank. Kind of a time-honored tradition of camp, right?”

“Got a jacket in the truck, you want one,” Cowboy Boots says to Jade. Probably because of the way her jaw’s chattering and the muscles around her eyes are jerking. But that’s not cold, that’s excitement. Usually Mr. Holmes will have cut her off by now, his big hand up between them, telling her he’s not letting her write any more papers on horror movies, sorry.

But she can do them out loud, too.

“The prank these kids dream up,” she explains, her voice gearing down, really getting into this, “it’s that they sneak a probably-fake human skull into Cropsy’s—into my bedroom while I’m sleeping, leave it there with two little candles burning in the eye sockets, and then bang on the window to wake me up. You can guess what happens next. The prank works—I’m scared, terrified, I’ve woken up to a nightmare—my cabin’s on fire! Lesson learned, right? Wrong. In my half-asleep panic, I knock this skull over, the sheets catch fire, and then for some reason I’ve got a full can of gas in there with me. Probably to keep it away from the kids. To keep them from hurting themselves with it in some stupid way.”

“Shit,” Shooting Glasses says.

“Now fast-forward five years after that explosion,” Jade says, like it’s a campfire they’re gathered round. “I, Cropsy, I lived through that burning . . . somehow. Kind of. Because I’m all melty and cratered, I wear trench coats, and my hat’s always pulled down low because any sunlight practically hisses against my tender skin, my pizza knots of scar tissue—this is three years before Freddy, cool?”

“Got some gloves too,” Cowboy Boots offers, starting to pull his off.

“I don’t need a glove,” Jade says, set up so perfect. “First person I kill, it’s with scissors.”

“Should we—?” Shooting Glasses says to everybody but Jade.

“Shh, shh,” Mismatched Gloves tells him, getting into this.

Jade grins a not very secret grin. “By the time I make it back to the lake Camp Blackfoot’s on, though—that’s Blackfoot—those scissors have gone magnum. They’re full-on hedge clippers now. And . . . why scissors, you think? Why hedge clippers? That’s what I’m wanting to get at here. Maybe you can guess it. My history teacher couldn’t.”

“There somebody we can call?” Shooting Glasses asks.

“Think back to that initial prank, right?” Jade says, stopping at each face like an interrogation. “Two candles burning like eyes in that skull? Now, say I just woke up, saw that in the very last part of what I’m going to come to consider the good part of my life, wouldn’t my first impulse be to cover those eyes, to ruin those eyes, to stop this scary shit from happening? But, if I just had a letter opener, say, I’m screwed. I have to either stick it in the left eye or the right eye, which doesn’t make the scare go away, it just turns it into a pirate. But, if I’ve got scissors like Schizoid from the year before, well. Then I can pop both eyes at once. They’re the perfect weapon for this terror I’ve woken up to. But now it’s five years later and I’m back at good old Camp Blackfoot, and there’s just a metric shit-ton of killing that needs to get done. So I ditch the scissors. Hedge clippers, though, with them I can stay back at a safe distance, just chop-chop-chop.” Jade mimes it for them, coming at each of their throats. They just watch her. “And anyway, hedge clippers, they’ve, one, never been used in a slasher before 1981, and, two, when held up so they kind of flash in the light, they kind of make you feel like you’re already dead.”

“Can I give you, you know, a ride somewhere?” Shooting Glasses asks.

“But also,” Jade barrels on, having to remind herself to breathe, “scissors and hedge clippers, they kind of fit the name, don’t they? Think about it. ‘Cropsy.’ If the name is at all descriptive, then it has to mean cropping things. Cutting them shorter than they were. Look it up in the dictionary when you get home. To ‘crop’ is to cut off the outer or upper parts. This is what I do as revenge to these campers, this summer. I crop the living shit out of them. In the woods. On a raft. In a mineshaft . . . all things we have right here in Proofrock.”

“What are you saying?” Cowboy Boots says, looking around like to check if he’s the only one of them wondering this.

“I’m saying that this is why I say I should be careful here,” Jade tells him, opening her hands to the fire. “If I get too close to this and go up in flames, then I’m going to come back in five years and carve through this town like, like—but I forgot to tell you all the other stuff. Shit. Did you know that on the set of The Burning, Tom Savini still had Betsy Palmer’s decapitated head from Friday the 13th, and the actors actually got to play with it like a volleyball? And, talking Friday, did you know it and Mother’s Day were filming across the lake from each other in 1979? Yeah, yeah, the crews would get together at night and drink beer, and they, no way could they have known that the f-f-floodgates were about to open, like—like those elevator doors in The Shining, right? It must have—it was, it had to be—can you even imagine—”

Jade hates it, but she’s crying a little bit now.

Maybe kind of a lot, really.

And now Shooting Glasses has her by the arm, his jacket off, around her shoulders.

He guides her away from the precious heat of the trashfire, delivers her into the passenger seat of a late-model dust-caked car that’s out of place for a construction site.

“I—I’m f-fine,” Jade finally manages to get out, trying to prove that it’s okay, she can stay, she can talk all night, she did all her slasher homework, she knows every answer, please, just ask, ask.

“I’m taking you to—” Shooting Glasses says from the driver’s seat, grubbing the keys up from the passenger seatback pocket, which makes it feel like his fingertips are touching her back. “Are you really, like, running from something?”

Jade considers this question for long enough that it becomes an answer.

“Where can I take you, then?” Shooting Glasses asks, cranking the engine.

“This your car?” Jade asks him back, wiping her face, finally breathing, and breathing too much now, too deep, like she’s about to just collapse into a girl-shaped column of tears and wishes.

“It’s like Cody out there,” Shooting Glasses says, nodding back to either Mismatched Gloves or Cowboy Boots. “We adopted it.”

Cowboy Boots, then.

“Adopted it your ass,” Jade says, pausing for a slice of a moment to clock if he hears that she’s talking like them. “Adopting a car means—it means you s-s-stole it.”

She hates shivering like this, showing weakness like this, having to have a body like this. But it’ll pass, she knows. You only shiver for a bit, when your body still has hope it can get back to warm.

“It was in the way of loading the barge last weekend,” Shooting Glasses says with an easy shrug. “We moved it in here to keep it from getting dinged up.”

“That d-doesn’t mean it’s y-y-yours.”

“We’ll give it back whenever whoever’s it is comes for it.”

“Maybe it’s m-mine,” Jade says, her shoulders jerking in spite of the jacket she’s wrapped in.

In answer to that, Shooting Glasses plucks a glittery pink Deadwood shirt off the dash, holds it up.

Jade has to smile, caught. No way can a horror fan claim a shirt like that.

“Now where we going, final girl?” Shooting Glasses says.

Jade’s heart stops, being called that. It stops and then inflates like a balloon in her chest. But, “That’s not me,” she has to say, looking out the side of the car, through her own reflection. “F-final girls are virg—they’re p-p-pure . . . they’re not like me.”

“Question stands.”

“I’ll show you,” Jade says, and nods to the right, into downtown Proofrock, then says to Shooting Glasses, “N-now you.”

“Me what?” Shooting Glasses says, easing the car one tire at a time over the fence panel laid on its side that Jade guesses is a gate. Close enough. When he turns the headlights on, though, she reaches across, touches his arm, shakes her head no. He sucks the light back into the front of the car. It makes it feel like they’re driving through church.

“I’d never even been here before,” Shooting Glasses says about Proofrock, sleeping all around them.

“Lucky,” Jade says, a wave of shivers rolling up her back again, her lips set against this physical betrayal. “Here.”

Shooting Glasses hand-over-hands the wheel to the left again, easing them past the drugstore, past the bank, and it’s not like church anymore. Now it’s like they’re coasting through a painting: “Quaint Mountain Towns.” “Lakeside Pastoral.” “What If 1965 Never Stopped Happening?”

“Your turn,” Jade tells Shooting Glasses. “I told you—I told you some stuff. Now you tell me some stuff. That’s how it works. Quid pro quo, Clarice.”

Shooting Glasses shakes his head side to side slow, apparently impressed that, in spite of these early stages of hypothermia, the girl’s still got it.

Jade nods that, yes, this is her, this is what she does.

“Where were you the last four years?” she says to him, kind of accidentally out loud.

“I was—” he starts, then hears it like she means it, just purses his lips, peers ahead into the unheadlit darkness.

“This is where you tell me about your buddy,” Jade explains to him. “The one that wasn’t a wake for back there. The one who didn’t die all the way or whatever.”

“Greyson.”

“Did he go live with a distant aunt to recover? Was her barn full of pitchforks, her hands full of s-sewing needles, her head full of bad ideas?”

Shooting Glasses looks over to her about this.

“That’s how it usually goes, I mean,” Jade explains, trying to show she means no insult. “The wronged party, victim of the prank, has to go somewhere long enough that everyone else can forget all about him, so it can be a s-s-surprise when he’s back.”

“You said this place was haunted,” Shooting Glasses tells her.

“By all the ghosts of who everybody used to want to be, before they died inside,” Jade says.

“What were you doing out here?” Shooting Glasses asks.

“Did you know Friday the 13th, it was trying to cash in on Halloween, yeah, sure, but then right at the very end it forgot what it was doing, started thinking it was Carrie?”

“Why do you talk about horror so much?”

“Slashers,” Jade corrects, is always correcting.

“I mean, and don’t take this the wrong way, but, have you considered that maybe you’re just hiding be—”

“Can’t I just like horror because it’s great? Does there have to be some big explanation?”

“I’m just, your leg, I think maybe that’s blood. I think maybe I should—”

Jade doesn’t hear the end because she’s popped the door, is rolling out into the cold, can’t take any more of this—her dad, this town, high school. Questions, glances, judgments. The sad way stupid Sheriff Hardy looks at her. The way Mr. Holmes is always asking her these exact same questions, every time she turns in a paper. Now even construction grunts she doesn’t know are treating her like she’s in need of special-delicate handling.

Fuck that. Fuck all of them.

She falls on the heels of her hands and her knees, doesn’t let that stop her, is already running like a ragdoll down the town pier, that kind of running that’s all untied boots, that you have to lift your chin for, because you know you’re going so fast. Halfway to the end of the pier, the stolen car’s brights blast on, throwing her shadow out ahead of her, where it plunges past the wooden planks, into the water.

Jade tries to stop but it’s slick, so, yeah, the perfect capper to the perfect night: she goes flailing over the end, just like every kid all summer long, except it’s not summer yet, and she’s seventeen, and it’s cold-thirty in the dead-dead morning.

The last thing she thinks as she’s slipping over the end is how stupid it is that that shaky light is steady for once, isn’t flickering out, and then she’s holding her breath for the icy plunge, is trying to insulate herself with slashers that happen in the snow but can only come up with Cold Prey and Cold Prey 2, and that’s not going to be enough to keep her blood from freezing.

Instead of splashing into the lake or cracking through the thin sheet of ice that has to be there, she thunks into the bottom of the green canoe always tied there, BYOP-style: Bring Your Own Paddle.

The canoe rocks and founders, doesn’t quite roll.

Jade sits up holding the back of her head, the world blurry and getting blurrier, then, hearing footsteps coming for her, she lets the scratchy nylon rope loose, reaches out with one boot to push off into the darkness, the scrim of ice on the surface crackling around her in large, slow sheets. So she won’t have to see Shooting Glasses standing there looking for her, she fetals down on her side in the bottom of the canoe, the gunwales to either side hiding her and her orange hair, her blue lips, her red left leg, her pitch-black heart.

And she hates it more than anything, but she’s sobbing now.

No, she can never be a final girl.

Final girls are good, they’re uncomplicated, they have these reserves of courage coiled up inside them, not layer after layer of shame, or guilt, or whatever this festering poison is.

Real final girls only want the horror to be over. They don’t stay up late praying to Craven and Carpenter to send one of their savage angels down, just for a weekend maybe. Just for one night. Just for one dance, please? One last dance?

That’s all Jade needs in the world, she knows.

Instead she’s got Tab Daniels for a father, Proofrock for a prison, and high school for a torture chamber.

Kill em all, she says in her heart of hearts. Let God sort them out.

Or just leave them unsorted, floating facedown in the shallows. That works too.

Jade chuckles to herself through the tears, pats her chest pocket for the cigarette she doesn’t have, because these coveralls were just hanging on the line.

Once she’s drifted far enough out that the light from the pier can’t reach her, she sits up, takes stock, and keeps monologuing even though the trashfire is just a flickering speck of light on shore: “Did you know that kid the shark eats in Jaws, his name’s ‘Voorhees’ too?” she asks the construction grunts, all three of them so ready to smile with wonder at this. “Yeah, yeah, Voorhees kids should maybe stay out of the water, think? But that’s not even what I meant to say, okay, sorry. I was just—when Jason comes up out of the water in mossy slow motion for Alice, floating there in her safe canoe, roll-the-credits music already cueing up, that’s Friday’s Carrie