Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

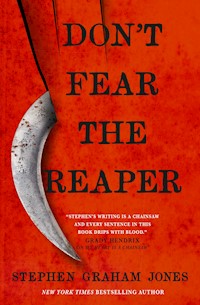

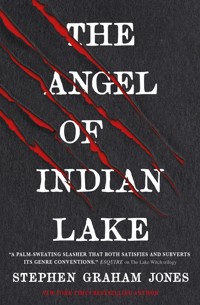

The most lauded trilogy in the history of horror novels concludes four years after Don't Fear the Reaper as Jade returns to Proofrock, Idaho, to build a life after the years of sacrifice—only to find the Lake Witch is waiting for her in New York Times bestselling author Stephen Graham Jones's breathtaking finale. It's been four years in prison since Jade Daniels last saw her hometown of Proofrock, Idaho, the day she took the fall, protecting her friend Letha and her family from incrimination. Since then, her reputation, and the town, have changed dramatically. There's a lot of unfinished business in Proofrock, from serial killer cultists to the rich trying to buy Western authenticity. But there's one aspect of Proofrock no one wants to confront…until Jade comes back to town. The curse of the Lake Witch is waiting, and now is the time for the final stand. New York Times bestselling author Stephen Graham Jones has crafted an epic horror trilogy of generational trauma from the Indigenous to the townies rooted in the mountains of Idaho. It is a story of the American west written in blood.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 714

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Praise for Stephen Graham Jones

Also by Stephen Graham Jones and available from Titan Books

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Here Comes The Boogeyman

Scary Movie

Batteries Not Included

Night Crew

House of Evil

Nightmare at Shadow Woods

The Night Has 1000 Screams

Bloodbath

Of Death and Love

Trick or Treat

The Last Ritual

The New Blood

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Praise for Stephen Graham Jones

“Stephen’s writing is a chainsaw and every sentence in this book drips with blood, every paragraph is clotted with skin, and every period is a bullethole. He makes me feel like an amateur.”—Grady Hendrix, New York Times-bestselling author of How to Sell a Haunted House and The Final Girl Support Group

“A homage to slasher films that also manages to defy and transcend genre. You don’t have to be a slasher fan to read My Heart is a Chainsaw, but I guarantee that you will be after you read it.”—Alma Katsu, author of The Deep and The Hunger

“Brutal, beautiful, and unforgettable, My Heart Is a Chainsaw is a visceral ride from start to finish. A bloody love letter to slasher fans, it’s everything I never knew I needed in a horror novel.”—Gwendolyn Kiste, Bram Stoker Award®-winning author of Reluctant Immortals and The Rust Maidens

“Stephen Graham Jones can’t miss. My Heart Is A Chainsaw is a painful drama about trauma, mental health, and the heartache of yearning to belong… twisted into a DNA helix with encyclopedic Slasher movie obsession and a frantic, gory whodunnit mystery, with an ending both savage and shocking. Don’t say I didn’t warn you!”—Christopher Golden, New York Times-bestselling author of All Hallows and Road of Bones

“An easy contender for Best of the Year. A love letter to (and an examination of) both the horror genre and the American West, it left me stunned and applauding.”—Brian Keene, World Horror Grandmaster Award and two Bram Stoker Award®-winning author of The Rising and The Damned Highway

“Jade Daniels is … the ultimate final girl. Bruised, battered, bleeding but never broken. Dark Mill South has no idea what he’s hit. Delivering characters as riveting as an axe to the face and surprise reveals like body blows, Don’t Fear the Reaper is another bloody triumph.”—A. G. Slatter, author of The Briar Book of the Dead and All the Murmuring Bones

“Stephen Graham Jones masterfully navigates the shadowy paths between mystery and horror. An epic entry in the slasher canon.”—Laird Barron, author of Swift to Chase

Also by Stephen Graham Jones and available from Titan Books

THE ONLY GOOD INDIANS

I WAS A TEENAGE SLASHER

THE LAKE WITCH TRILOGY:

MY HEART IS A CHAINSAW

DON’T FEAR THE REAPER

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

The Angel of Indian Lake

Print edition ISBN: 9781835410264

E-book edition ISBN: 9781835410271

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: March 2024

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Stephen Graham Jones 2024.

Stephen Graham Jones asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

for this kid named Jason.I would have swam out for you, man.we all would have.

There’s never been a final girl like this.

—Carol Clover

HERE COMES THE BOOGEYMAN

The Savage History of Proofrock, Idaho opens looking through the two eyeholes of a mask, with some heavy, menacing breathing amping up the menace.

What those eyeholes are fixed on from behind the bushes is a ten-year-old kid. It’s nighttime, well after midnight, and the kid’s sitting on a barely moving swing at Founders Park. It’s where the staging area for Terra Nova used to be, eight years ago.

The kid’s head is down so his face is hidden. He could be dead, posed there, his hands wired to the swing’s galvanized chains, but then a thin breath comes up white and frosted, and he starts to look up, eyes first.

Before his face comes into focus, The Savage History of Proofrock, Idaho cuts to an occluded angle into . . . a shed?

It is. A dark workshop of some sort, like a room you scream through at a haunted house down in Idaho Falls.

No more mask to look through. Just a nervous space between two boards of the wall.

Words sizzle into the bottom of the screen and then flame away: tHe ChAINsaw’s bEEN DEAd for YeARs. The irregular capitalization is supposed to make it scarier, like a ransom note.

In this shed, on this grimy workbench, a man in a leather apron is working on this chainsaw. This man’s got a bit of size—linebacker shoulders, veins cresting on his forearms. His hands are white and tan, and the camera stays on them, documenting his every ministration on this chainsaw.

It’s dark, the angle’s bad and unsteady, but that only makes it better, really.

“Is that Slipknot?” Paul says about the music thumping in this shed.

Hettie shushes him, says, “He’s old, okay?”

He’s old and he’s taking the top cover off the chainsaw, or trying to. Eventually he figures out to push the chain brake—the cover comes right off. It’s enough of a surprise that the cover goes clattering onto the floor, almost loudly enough to cover the squeaky yelp that’s much closer to the camera.

Almost loud enough to cover that, but not quite.

Instead of a nightmare face stooping down into frame after this runaway chainsaw cover, there’s twelve seconds of listening silence after the song’s turned off. The man’s hands are still on the workbench, the fingertips to the dirty wood, the palms high and arched away so it’s like there’s two pale spiders doing that thing spiders do when their cluster of eyes and their leg bristles have told them there’s a presence in the room.

And then that grimy leather apron is rushing to this camera, blacking the screen out.

Paul chuckles, draws deep on the joint and holds it, holds it, then leans forward to breathe that smoke into Hettie’s mouth like she used to like, when they were fourteen.

“You’re going to secondhand kill me,” she says with a satisfied cough, holding the videocamera high and wide, out of this.

“Only after I first-hand do something else . . .” Paul says back, his hand rasping up the denim of her thigh.

“But did it scare you?” Hettie asks, keeping his hand in check and shaking the camera so Paul’s syrupy-thinking self can know what she’s talking about: the documentary.

She pinches the joint away from him for her own toke, and doesn’t cough it out.

Where they’re sitting is the doorway alcove of the library on Main Street, right under the book deposit slot. Out past their knees, Proofrock’s dead. Someone just needs to bury it.

“Your mom know you snuck Jan out after dark?” Paul asks, squinting against Hettie’s exhale.

“She’s more worried about who my dad’s dating this week in Arizona or Nevada or wherever,” Hettie says from the depths of her own syrup bottle. “Janny Boy’s a good little actor, though, isn’t he? I told him to pretend he was a ghost, just sitting there.”

“What’d you do with the snow?” Paul asks, his eyes practically bleeding.

It’s nearly halfway through October, now. The snow they always get by Halloween hasn’t come yet, but there’s been plenty of small ones, trying to add up into the real deal.

“I edited it out,” Hettie says, sneaking a look up to Paul to see if he’ll buy this, but his stoned mind is still assembling her words into a sentence. Hettie shoulders into his chest, says, “We shot it in July, idiot.”

“But his breath,” Paul manages to cobble together, doing his fingers to slow-motion the puff of white Jan had breathed out that night.

“I didn’t give him a cigarette, if that’s what you’re asking.”

“So he’s really a ghost?”

“Confectioner’s sugar.”

“In his mouth?” Paul asks.

Hettie shrugs, says, obviously, “He loved it.”

“Ghosts and swings and baking goods,” Paul says, hauling the camera up to his shoulder, aiming it at Hettie. “Tell us, Herr Director, why do little ghost boys with sweet white mouths like to frequent parks after dark?”

“Because it looks good for my senior project,” Hettie says, cupping the lens in her palm, guiding the camera down.

It would be easier to shoot this documentary with her phone, which is much better for low-light situations, but this is throwback. Her dad’s VHS camera was still in the attic, along with everything else he’d left when he bailed, but Hettie’s paying for these blank tapes herself, “to show she’s committed,” that “this isn’t just another passing thing.”

What it is is her ticket out of here.

The world will roll out the red carpet for footage like this, from the heart of the murder capital of America. First there was Camp Blood half a century and more ago, then there was the Independence Day Massacre when she was in fourth grade, and then, for junior high, there was Dark Mill South’s Reunion Tour. Forty people dead in a town of three thousand is a per capita nightmare, even across a few years.

And that translates to serious bucks.

Now if she can only get this Angel of Indian Lake’s tattered white nightgown and J-horror hair and supposedly bare feet on tape tonight, blurry and distant, “ethereal and timeless,” then . . . then everything, right? The doors to the future open up for Hettie Jansson, and she walks through with a Joan Jett scowl, squinting from the sea of flashing cameras but not ever wanting them to stop, either.

The problem, though, it’s that the Angel isn’t reliable, is probably just some practical joke the jocks have kept going all the way since summer. Joke or not, though, she’s the missing ingredient for The Savage History of Proofrock, Idaho, the piece that sends it into the horror stratosphere. And they’ve got all night to fit her into a viewfinder, hit record, and hold steady fifty-nine and a half seconds—it’s how long that famous Bigfoot recording is, right?

And if the Angel doesn’t show tonight, then there’s still two more weeks of nights until the rough cut’s due. Two more weeks and the rest of the stash Paul liberated from a bright orange Subaru some nocturnal tourists left unlocked for their big skinnydipping expedition.

Sorry, Colorado, Paul keeps saying, every time he’s rolling another fatty from the Subaru. The license plates had been white mountains on a green background—the first car you try if you’re in a red state, are looking for something to smoke.

Sorry, GPA, Hettie always adds, watching Paul’s fingers roll, tighten, twist.

But she’s not.

Soon, she’s past all that.

“What’d you use for . . . at the beginning?” Paul asks, his hands making binoculars over his eyes.

The mask point-of-view—slashercam, Hettie knows to call it, now.

She lets this toke out slow and languorous, imagining herself a movie star from the thirties, and hikes what Paul’s asking about up from the front pocket of her jean jacket, where it’s been since before the semester started.

“Shi-it . . .” Paul says, and holds the little circle of black cardboard up to try to look through. The two eyeholes are sized for an action figure, though, not a full-size burnout.

“Trick of the trade,” Hettie says with a shrug, fitting that cardboard circle into the lens so Paul can peer through the eyepiece, see the magic himself.

He stands, feels ahead with his left hand, the right holding the camera to his face.

“Look, look, I’m a killer!” he says. “Somebody do something sexy, so I can stab you!”

Down Main a little ways, a lone light fizzles on, holds itself wavery bright for a few seconds, then dies back down.

That too, Hettie tells herself.

She’s going to document it all, she’s going to lay Proofrock bare, she’s going to show the world this place she grew up in. No, this place she survived.

“Push play,” she says, pulling Paul back down beside her.

When he can’t figure it out—This is your brain on drugs—Hettie does it for him.

On the little screen, now, The Savage History of Proofrock, Idaho is moving through the cemetery like a balloon let go, a balloon that’s lost most of its helium, so it’s just riding along about two feet off the ground.

“No, Het, you can’t—” Paul says, pushing the camera away.

Hettie tracks up to him but doesn’t stop playing the footage.

She knew this was going to be the hard part for him. His aunt was Misty Christy—the most prominent headstone in that scene. Her daughters, Paul’s cousins, the little sisters he never had, are the reason Hettie knows he’ll never be leaving Proofrock. The whole week leading up to the Fourth back then, Paul had been chasing his little cousins around with all the shark stuff he had—he was a fan, lived for Jaws, probably watched it once a week that summer, until he knew all the lines, couldn’t stop saying them.

The night-of, he was one of the ten-year-olds with a fin strapped around his ribs, a snorkel chimneying off the back of his head, eyes in scuba goggles, a wide carnivorous smile on his face.

In 2015, there had been no one more excited for the movie on the water than Paul Demming. Hettie still remembers him standing from his parents’ stupid raft to sing that Spanish Ladies song, and how it looked like he felt like he was leading that song, that he was part of this adult world now, part of Proofrock, of Indian Lake.

And then, half an hour later, he was trying to drag his aunt up onto shore, and his dad had to pull him off her when he kept trying to breathe into her lungs, even though half her head was gone. Hettie’s pretty sure that that’s where her love affair with horror started: seeing Paul at ten years old in the shallows, fighting with his dad, his whole lower face slathered red.

“It’s a memorial for all of them,” Hettie tells Paul about the cemetery Steadicam, as she calls it, and passes him the joint, has to hold it there for probably ten seconds before he finally rips it from her fingers hard enough that some of the cherry crumbles away, its small light leaving slow orange tracers in the dark.

Paul draws deep, painfully deep, like punishing himself. Like he can erase the past, just be from somewhere else, please. Somewhere normal.

His fingers are shaking now. Hettie creeps her hand over, holds them still.

“I hope you really do get out of here someday,” he says to her, snuffling his nose.

“Watch,” Hettie says.

The Savage History of Proofrock, Idaho is still playing. She props the camera between them, they resituate to see better, and—

“Fucking Rexall,” Paul mutters.

Which is what the words at the bottom of the screen should say. But it already took Hettie all weekend just to get those ransom note letters in place.

Less of that from here on out, thanks.

This isn’t technically due until January, but if she wants to get it into any of the spring filmfests, she needs to have it wrapped a lot sooner than that.

And? It’s counting for the interview portion of senior History, and that is due before the semester’s over. Without it, no graduation in June. No blasting off into the world beyond Idaho.

On the little screen, Rexall’s blurry at the far end of a long hall in the elementary. He’s sitting on a mechanic’s stool, has his tool bag beside him, is doing something to or with the fire extinguisher cabinet.

“Installing another perv camera?” Paul asks, pulling the screen closer and angling it back and forth like that’ll let him see deeper into the frame.

“It’s not the girls’ locker room,” Hettie mumbles. Still, she does have extensive footage—with her cellphone—of every square inch of that fire extinguisher cabinet. For whatever that’s worth. All she ever found was “Rx” on the fire extinguisher’s inspection label.

She’s thinking she might should cut Rexall, really. Knowing him, he’ll think he’s the star, the glue, the beating heart of Proofrock. When really he’s just the scum floating on the surface.

Hettie taps the fast-forward button three or four times, bounces past the high school.

“Oh, yeah, gotta have that,” Paul says then.

Terra Nova, glittering across the water.

When Hettie was a freshman, Terra Nova was still burned ruins, too thrashed out and spooky to even drink beer in. Now, though, it’s coming back to life, construction crews working twenty-four seven again.

She still remembers walking single file from Golding Elementary to see the barge carrying that big bulldozer across Indian Lake. She was the caboose that day, which Ms. Treadaway told her was the most important place in their waddling train of Goslings—it was her job to make sure everybody stayed on the tracks, see?

Hettie was so proud to get to be the caboose.

And it was such bullshit.

But that doesn’t change how it felt, watching that barge balance on top of the water. It should have sank, she knows. It should have leaned over far enough to one side or the other to plunk that big yellow tractor down to Drown Town, into Ezekiel’s Cold Box.

“Idiots,” Paul says about Terra Nova.

It’s a sentiment Hettie shares. And most of Proofrock, this time around.

Not that anybody can do anything about it.

“You’re not supposed to say that,” a small voice says from the darkness, startling Paul enough that he drops the joint, throws an arm across Hettie like protecting her from going through a windshield.

The Angel doesn’t speak, though. And this non-Angel’s a whole lot shorter, anyway.

“Jan?” Hettie says, standing, fighting out of the safety of Paul’s arm.

Her little brother steps into the weak light coming through the glass door from some glow in the library, the long blond hair that always gets him mistaken for a girl hanging half over his face.

“Guess the ghosts are walking tonight . . .” Paul says with appreciation.

Jan’s done his own ghost make-up this time. Meaning he probably left a mess in the kitchen—great. Confectioner’s sugar everywhere. Just what Mom needs, come morning.

“He must have seen me leaving with this,” Hettie says, hefting the camera.

“I want to be in the movie some more,” Jan says, his lower lip starting to push out, meaning the waterworks won’t be far behind.

Hettie steps out, scoops him up, situates him on her hip. He weighs probably half as much as her, she knows, but she also knows that a woman’s hips can hold anything. Especially a little brother.

“What smells funny?” Jan asks.

Paul fans his hands at the smoke danking up the alcove.

“Moths with dirty wings flying into that lightbulb,” Hettie says, walking the two of them out onto the grass.

Behind them, Paul’s phone buzzes.

“What?” Hettie asks, lasering her eyes to his.

“Waynebo,” Paul says with a shrug.

“What, he finally found it?”

“I think it’s a butt dial?”

This makes Jan laugh in Hettie’s arms. “Butt dial” is his favorite term. Along with anything else to do with butts.

“Can we at least . . . not have my dead aunt’s name in it?” Paul says then. “I don’t want people making fun of it, yeah?”

Hettie notes that he’s crushing their roach under the heel of his combat boot. It’s against his religion to waste, but he’s protecting Jan from their bad influence, Hettie knows.

“But I’ve already—”

“Reshoot,” Paul says. “What’s it called? ‘Pickups’?”

“Do you know how hard it is to edit actual videotape?” Hettie asks. “I have to—”

“I’ll help,” Paul tells her.

They both know he’s lying, that he’ll just kick back on her bed and throw a rubber ball against the ceiling the whole time, leaving Hettie to convert the VHS to digital, play it on her laptop, then paste letters or whatever on the screen and record enough stop and start shots of that—because the scan rates don’t match up—to add up to a second or three of continuous footage.

“Just to be sure I’m hearing you right,” she says, using her mom’s point-by-point voice, “you want us to go to the cemetery on Friday the 13th, at night, with—?” Instead of saying the last part, she mimes the joint they were just smoking.

“Maybe we could skinnydip while we’re there too?” Paul says.

Hettie looks out over Proofrock, shrugs what the hell.

“Maybe that’s where she is, right?” she says about the Angel, looking over in the direction of the cemetery.

“Bet so,” Paul says, playing along.

Ten minutes later, via a coasting motorcycle ride Jan’s not to ever mention again, under threat of having his butt cut off, they’re at the cemetery.

“I’m coming to get you, Barbara . . .” Paul tries, his voice up and down, fake spooky.

“Her name is Hettie!” Jan yells with a thrill, just to be involved.

Paul cocks his bike up on its kickstand and Hettie guides the oversize helmet up off Jan’s head. He was sandwiched between them for the ride over.

“Stay here,” Hettie says to him, stationing him with Paul, and cues into the blank tape at the end of The Savage History of Proofrock, Idaho so she can do her version of Steadicam: her purse strap unlatched, then hooked through the front and back connections on the top of the videocamera. She hangs the camera by her leg a little ahead of her, hits record, and is walking through the graves again—so many, since 2015—this time avoiding Misty Christy’s headstone, even though this scene’s going to lose some of its oomph now, from being censored.

Still, it’s Paul, right? Paul who she actually trusts with Jan. Paul who she’s broken up with probably a dozen times since junior high. But they always find each other again, don’t they? When you’re a reject in Proofrock, have undercuts and piercings and intricate plans for full sleeves, you can’t stay away from the one other person drawing on their arm with a ballpoint pen.

If only she could take him with her when she leaves.

But don’t think about that now. You’re a filmmaker, she reminds herself. You’re documenting, you’re documenting. And, never mind that the smart kids in horror movies avoid graveyards at night.

This is for school, though. And it’s not like they’re drinking beer on the actual headstones, it’s not like they’re sparking up—they’re being respectful, observing the rules . . . It’ll be fine, Hettie tells herself.

Until she looks up from her feet and the camera that’s so hard to keep from spinning, sees the grave over by the fence.

It’s where the county buries those who don’t have anyone to bury them.

And, “grave” isn’t the right word. Not anymore. More like “hole.” More like the crater left after an eruption. Either somebody dug this dead person up, or that dead person clawed through the dirt themselves, and walked away.

“What the what?” Hettie says, pulling the camera up to her shoulder to document the living hell out of this.

Through the viewfinder she can read the name: GREYSON BRUST.

“Who?” she mutters, trying to dredge up anyone in school with a last name Brust, but is interrupted by snow crunching behind her. She turns fast and scared, is already falling away, one arm out to block whatever’s coming.

It’s Paul. He’s got Jan on his hip.

“What?” he says, holding Jan halfway behind himself.

Maybe Hettie won’t leave him?

Maybe she’ll just stick it out here in Proofrock like her mom, and forget about who she used to want to be, where she wanted to go. How she was going to have the world wrapped around her finger. When you’ve got someone’s whole hand to hold, that can be all that matters, right? That can be enough.

“Look,” she says, stepping to the side.

Paul edges up to the open grave.

“Who’s he?” Paul says about this “Greyson Brust,” and then reaches for the lens, points the camera to the light snow to her left, his right.

Tracks.

Hettie lowers the camera, her face slack.

“I don’t—I don’t—” she stutters.

“I’m the map, I’m the map!” Jan says, bouncing in Paul’s arms.

It’s from Hettie’s old Dora the Explorer DVDs. He’s addicted to them.

And he’s right.

If they follow these tracks, then they get to the, to the—to the what? The dam, the way the tracks are headed?

Except: why is Paul just staring at the tracks like they don’t make sense?

His phone buzzes and he rearranges Jan, reads the text.

“Don’t fucking believe it,” Paul says, holding the phone face out like this proves it. “He found it.”

What Waynebo—Wayne Sellars—has been on the trail of all summer is what some out-of-state hunters are supposed to have stumbled on in the woods, when they were lost themselves: half a white Bronco. Maybe three-quarters of one, if it held together enough for its long roll down from the highway. Because they were traditional hunters, though, just stickbows and compasses, even had fringe on their canteens, they hadn’t been able to direct anybody back to wherever they were. Everybody knew that was shorthand for the two having been hunting where they weren’t supposed to be—bows without wheels are quiet—but that didn’t make the Bronco any easier to find.

The Bronco’s pretty much the last mystery left in Proofrock, though: after Dark Mill South brought his special brand of violence to town, a trucker had reported a Ford buried nose-first into a snowbank on the high side of the highway—the temporary grave of the previous sheriff and his deputy. Because there had been so many dead in Proofrock to deal with, though, Highway Patrol had just cordoned the Bronco off, set some rookie up to guard it, and then not got Lonnie to drag it out for a week.

It turned out not to be the whole truck, but just its ass end. Evidently it had been hit broadside by Dark Mill South’s stolen snowplow, at speed, and then had just slid sideways in front of that big blade until it calved off in either direction. The Bronco’s tailgate and rear bumper landed upright in the snow on the high side of the road, and the rest of the truck? That was the thing: Where? Directly across from that tailgate and bumper made sense, but the thing is, wrecks don’t have to make sense. On the down side of the highway, the Indian Lake side, the country was rugged and rough, deep as hell, and not even a little bit forgiving. And it doesn’t give up its dead until it wants to.

Which, according to Waynebo, must be tonight.

He’d spent the first week of summer gridding Fremont County up on his computer, somehow plugging that into a hand-held GPS he had, and ever since then he’d been working those imaginary lines back and forth on his horse, insisting the Bronco had no choice but to show up. And, now that it maybe had, he was going to be the one to collect the twenty-five-hundred-dollar reward Seth Mullins, the deputy’s husband, had somehow pulled together, for whoever found his wife’s body.

Well, Waynebo was going to collect that twenty-five hundred and the ten grand Lana Singleton had added on, because, as she said in the announcement in the Standard, Proofrock needs to heal, doesn’t it?

“He wants you to bring your camera,” Paul says, lowering his phone. It won’t stop buzzing with Waynebo’s celebration.

“He doesn’t have his phone?”

“He says this should be in your movie.”

“But the footprints,” Hettie says, about the tracks in the snow.

“About those . . .” Paul says, kind of like he . . . regrets saying it?

“What do you mean?” Hettie asks, stepping in to see.

Paul waits for it to make sense to her. There are footprints like there should be—even in snow this light, you can’t avoid them—but it’s just the front part of some dress shoes? Then Hettie sees it, has to gasp a little: to either side of the footprints, the fingers leaving clear ridges, there’s handprints as well.

“Like this,” Paul says, and slings Jan onto his back like a cape, Jan squealing with delight.

Paul leans forward beside the tracks, and he’s right: his hands are wider than his feet, and only the front parts of his combat boots are leaving prints in the snow.

“I don’t underst—this doesn’t make sense,” Hettie says. “The Angel, she . . . she walks, she’s upright.”

“Angel?” Jan asks, excited.

“She doesn’t wear shoes either, does she?” Paul says.

“Meaning?” Hettie asks.

“Meaning we’re in a cemetery at night on Friday the 13th,” Paul says, popping up easily with Jan on his back. “I’m not just super sure things are supposed to make sense. Why come out here to dig someone up. Why leave on all fours.”

“Maybe they fell down,” Hettie tries, trying to squint it true.

“Maybe,” Paul says, but he’s not buying that.

“And where are the tracks coming in?” Hettie asks, trying to make sense of the snow they’ve trampled.

“More important,” Paul leads off, shifting Jan around to his side, “would you rather follow these tracks and film some sick graverobber, or, would you rather . . . you know. Solve the biggest mystery in town?”

“It’s videotape, not film,” Hettie mumbles, kind of bouncing on her feet, not sure which way to go.

“These tracks’ll still be here tomorrow . . .” Paul says with a shrug.

In his arms, Jan does the same shrug.

It’s so damn cute.

“But we call it in?” Hettie says, slinging the camera around her neck like the purse it isn’t.

“We can be he-roes,” Paul sings, and leads them back to the motorcycle, going through what he knows of the rest of the song, which isn’t much.

Half an hour later, three on the bike again, they’re picking their way down the rut-road that eventually tiptoes under the dam, crossing Indian Creek at the big clearing and going back where the hunters go. Hettie wants to get a shot from there, of the dam looming over them. Maybe she can even superimpose a Jaws poster over all that concrete? It might be perfect—the image that sends Savage History viral, into the stratosphere.

Just that lone swimmer, and the shark coming up from the depths for her.

Jan’s helmet bounces up for the fiftieth time, taps her in the chin.

She’s the one holding Paul’s phone now, directing them to the pin Waynebo dropped, that he insists is so top secret that this message is probably going to self-destruct—sorry, Paul’s phone. As soon as they stop, she keeps telling herself, she’s hauling her own phone out, to call the grave robbing in.

But they’re going so fast. It’s like this night’s a slip ’n slide. She took one tentative step out onto it and now she can’t stop, is just going faster and faster. Weren’t they looking for the Angel? How’d that turn into a tour through the graveyard, and now a stab out into the timber to see a dead body or two?

This is Proofrock in October, though, she knows.

Once the clock strikes midnight, anything can happen.

Two hundred yards up, Waynebo’s paint horse is standing in the road, its reins hanging down by its feet.

Paul slows, his feet to the ground to keep them from falling over.

“Just up here,” Hettie says, and Paul takes them into the tall grass dusted with snow, to keep from spooking Waynebo’s horse. Under Hettie’s chin, Jan’s helmet pivots slowly. He’s watching that horse with wonder. There’s something about horses at night, isn’t there?

Hettie’ll have to come back, get this on tape too.

This documentary is going to be longer than the twenty minutes she promised Teach. Much longer.

Proofrock just keeps opening up and opening up, doesn’t it? And then she decides that, no, she won’t superimpose Jaws on the dry face of the dam, she’ll get those elevator doors from The Shining up there, with blood crashing through, to paint the valley red—just how Savage History already opens up. Which is to say, all she’ll have to do is project Savage History up there. It’ll be perfect.

“There,” Paul says, because he’s the only one not looking back at the horse.

It’s the front part of the Bronco, lodged in a thick tangle of falldowns, their root pans making a sort of cradle around the wreck, the better to hide it. And, really, Hettie can tell, this is where the wreck rolled down to, and recently, judging by how the pine needles it jarred loose are on top of the crust of snow.

Paul stops, waits for Hettie to lift Jan down before rocking the bike onto its kickstand. The way he does it, there’s something fifties about it, like he should be rolling the cuffs of his jeans and combing his hair back until it’s a perfect ducktail.

No, Hettie isn’t leaving Proofrock, she knows. And she guesses she’s always known, goddamnit.

Home is where your heart is, though, isn’t it?

And her heart’s parking the bike, right now. And setting her little brother up on it, and telling him to wait here, to not get down no matter what, okay?

Jan nods his little-kid nod, his eager-to-please nod.

“Promise?” Hettie says to him, and he nods faster, is thrilled just to be tagging along for this grand nighttime adventure.

“I can’t believe this . . .” Paul says, about the Bronco actually finally being somewhere.

“Are they still in it?” Hettie says, stepping around, leading with her camera, not sure if she wants to see actual dead people or not.

Paul has his phone’s flashlight on, winking on a piece of red reflector somehow embedded in the trunk of a tree. He steps forward gingerly, and Hettie sees that the passenger side of the Bronco isn’t just crushed, it’s flattened.

“Shit,” Paul diagnoses.

Hettie nods slowly, has to agree.

“It was probably caught upslope for the last four years,” Paul mansplains, looking up there. “The trees holding it finally got cold enough to snap, and—”

“It rolled the rest of the way down,” Hettie finishes. Then, “But are they still . . . ?”

Paul shines his silvery light into the cab, and, just like in Jaws, there’s a rotted head bobbing up into the brightness.

Hettie and Paul both fall back, holding onto each other.

The camera dislodges into the grass and snow, some button jarring the tiny heads into furious motion. When no zombies lumber up from the wreck to eat their brains, Paul laughs an embarrassed, nervous laugh. Hettie knows she should as well, because it’s so stupid it’s funny, except—

She’s seen these movies.

That might just be a cat in a closet, but there’s probably a penis-headed alien bug unfolding from the backseat, its mouth already slavering.

“What?” Paul says, holding his hand up, fingers spread away from each other.

With his phone, he lights them all up.

Blood.

He spins around on his ass and hands, drops his phone, has to get it back from the snow, and—and . . .

It’s Waynebo.

“No,” Hettie says, or hears herself saying, not even aware of having pushed back from all this already.

Waynebo’s been ripped open. His blood looks so red, so fake.

Hettie crabs farther back, her arms and movement stiff, no scream erupting—she knows not to put that bullseye on her back.

Any more than it probably already is.

“Paul, Paul, Paul,” she gulps out, still trying to buttslide away, which turns out to be into the missing door of the Bronco.

A rotted skeleton arm falls down on her shoulder and what’s left of the truck settles down with a sudden whoompf, nearly crushing her.

She flinches away, surges almost all the way up, her feet already running, never mind if the rest of her’s ready.

“Paul, Paul! We need to—!”

She stops a step or three away because: Paul?

Hettie desperately pans around to every quadrant. Except you can’t watch all of them at once. Your back’s always to one of them.

She spins, spins again, stumbles, is about to cry, can feel it welling up in her throat, in her chest, in her soul.

“Paauuulllll!” she calls out all around, who cares about bullseyes now.

She shakes her head no, that she doesn’t want to make the documentary anymore, that she’ll stop, she’ll throw it away, she’ll do something normal for her senior project.

The woods don’t answer.

She hugs herself, still looking left and right and behind her.

“Paul?” she says, quieter.

She falls to her knees, shaking her head no, no, please, and fastcrawls ahead to the videocamera, its light blinking record-red, now.

Hettie claws it to her to use like a hammer, to swing at whatever’s coming, and inadvertently hits play, then drops the camera when she turns around fast, sure something was just behind her.

On the small screen of her videocamera in the snow and yellow grass, the documentary is playing back, now.

It’s past the cemetery, is to . . . the Pier.

It’s a wide shot from the side, and’s far away but that’s just to make it feel like she’s spying, like she’s not supposed to be seeing this.

Really, though, she knows the sheriff.

He was the one getting that chainsaw going, to Slipknot—his choice.

It was setup for this: to the end of the Pier, now, Sheriff Tompkins fires that chainsaw up, its blue smoke gouting up into the night sky in a way that would make David Lynch sigh with contentment, a way that would make Martin Scorsese have to wipe a single tear away.

Sheriff Tompkins revs that chainsaw once, twice, then takes a knee like he’s going to saw through the planks of the new Pier, and now Hettie’s over his shoulder for this dirty-loud work.

He’s not chewing those fast teeth into the Pier, though. He’s chainsawing the town canoe in half, the blunt leading end of the blade frothing the lake water, the pale, gummy fibers of the hull writhing and flailing.

It’s supposed to mean Proofrock’s slasher days are over.

The chainsaw chugs through the green fiberglass and finally the canoe falls into two pieces, both of them Titanic’ing down into the murky depths, and then it’s a wide shot again: Sheriff Tompkins holding that chainsaw up and shaking it at the gods.

Just as Hettie wrote it.

In the viewfinder of her camera, though, nothing’s scripted. Or, it was all scripted long before she was born. Hettie’s on her knees, she’s spinning around again, she’s sneaking a look to her camera like to pick it up again, but then the rabbit in her senses she’s . . . not alone?

She clamps her hand over her own mouth, holds her breath, muffling what would have been her scream.

Slowly, so as not to draw attention, she turns, and whatever she sees just out of frame makes her fall away and then rush to the side, which is right into the camera.

A flurry of motion later, her face slams down right in front of the lens, comes up caked with snow. The blood from her nose and mouth is bright against that whiteness, is either stringing away from her or trying to hold her together, and she’s still reaching ahead, like the camera’s heavy enough that, if she can just grab it, it can become her weapon, her savior, her way out of this, whatever it is.

But she only manages to jostle it the littlest bit.

Her face is still filling that viewfinder slightly off-center, and her hand is reaching around to the controls, to push record, so she can say something.

“Mom,” she whispers right into the camera, her voice shaky, and then she’s ripped to the side like Chrissie in Jaws, some snow flecking up onto the lens, distorting the left side of the frame.

Moving from bubble to bubble through it is . . . it’s more upright than a dog or bear, is nightgown-pale, black and loose at top, like a headful of hair.

So much hair.

A woman.

The Angel of Indian Lake.

She’s ethereal and wrong, dead except for the walking-around part, and when the thing perched on Hettie steps off of her—snapping from bubble to bubble on the camera lens, it’s a man on all fours, a pale man in the tatters of a suit—when this thing that’s also dead approaches her, its head dipping obsequiously over and over, as if it knows it’s in the presence of its god, it’s also . . . dragging something?

Something large and squirming, held between its teeth like an offering.

Which it lays at the Angel’s feet.

After a moment of what feels like consideration, the Angel lowers herself to this offering, then looks sharply up at the thing that delivered it to her.

A flurry of motion later, the thing’s head is rolling across the lens, past the bubbles to the clear part, where a pause would show a staticky human face, mouth ringed with blood, eyes hollow, hair still perfectly in place from whatever glue or spray the embalmer used.

And then it’s gone. As is the Angel.

All that’s left in the camera eye is the top of the tall grass and the pale crust of the snow and the trees and then, forty or fifty feet out, centered just like Hettie would have done if she were operating this camera, the motorcycle.

There’s no little boy up on the seat.

The Savage History of Proofrock, Idaho isn’t over, no.

It’s just getting started.

SCARY MOVIE

This isn’t Freddy’s high school hallway, this isn’t Freddy’s high school hallway.

If it were, Tina would be twenty feet ahead in her foggy plastic bodybag, being dragged around the corner on a smear of her own blood.

Instead—again, but it always feels like the first time—I’m the one in that bodybag.

I’m helpless on my back, there’s no air in here, my feet are travois handles to pull me with, and the lockers and doorways and educational posters and homecoming banners to either side are blurry, are in a Henderson High I’m not part of anymore.

Not since Freddy got his claws into me.

I want to scream but know that if I open my mouth, what’s coming out is a sheep’s dying bleat. I clap my scream in with my palm, try to clamp my throat shut, tamp the panic down, but my elbow scraping on the plastic wall of this bodybag rasps louder than it should, and—

He looks back.

His face is scarred and cratered, and there’s a glint of humor in his eyes like he’s getting away with something here, a glint that spreads to his lips, one side of his twisted mouth sharpening into a grin right before his head Pez-dispensers back because his neck’s been chopped open, and what comes up from that bloody stump is the grimy hand of a little dead girl fighting her way back into the world, and—

And it doesn’t have to be this way, according to Sharona.

She’s my twice-a-month therapist, courtesy of her champion and main benefactor, Letha Mondragon.

It’s only a movie, it’s only a movie, Sharona’s taught me to repeat in my head.

To fight my way through panic attacks, I’m supposed to think of my life as playing on a drive-in screen. Not that I’ve ever been to a drive-in. But evidently, late in their evolution, there would be six or eight or ten drive-in screens all in this big-ass Stonehenge circle, each with their own parking lot. If you didn’t like what was playing on one screen, you could take your popcorn, cruise over for the next movie, and the next, until you found one that worked for you, that helped you through this night instead of trapping you in it.

“You’re the consumer here,” Sharona told me so, so earnestly our first session. “And what you’re paying with is anxiety and dread and panic, see?”

The first part of me being the one carrying the popcorn, it’s supposed to be buying into this being all a movie, all a movie. Like that was ever enough to keep the horror in The Last House on the Left from touching you where it counts.

Sharona doesn’t know horror, though. Just feelings, regrets, strategies, and how to see through my own rationalizations and paranoia, my bad history and worse family shit.

I say quid pro quo to her a lot, but I don’t think she ever really gets it like I mean it.

The way she explains what I’m feeling in moments like this—“feeling” being clinical-speak for “consumed by”—is that my anxiety is a straitjacket constricting me: at first it feels like a hug, like something I should nestle into, but then . . . then it doesn’t know when to stop, does it, Jade?

StraitJacket of course being a 1964 proto slasher, post-Psycho but very much providing a model for Psycho II nearly twenty years later. Thank you, Robert Bloch.

Sharona has it wrong about straitjackets, though. In a straitjacket, you can breathe. I know this from experience. You don’t open your wrist out on the lake and then get trusted with your own fingernails and teeth, I mean.

Where you can’t breathe, though?

In a bodybag.

When Proofrock and all what I’ve done and not done and should have done if I were smarter and better and faster and louder are collapsing in on me and there’s no air at all, then a knife finger materializes blurry and real through the foggy plastic cocooning me, it materializes and then it loops through a delicate metal tab, to zip me right in.

Sorry, Sharona.

One bullshit tool you’ve given me to work that zipper down from the backside is to write letters to someone I respect or care for, who could and would offer me a helping hand, to clamber up out of this.

Which is just a reminder that everyone I love is dead, thanks.

Sheriff Hardy. Mr. Holmes. Shooting Glasses.

I don’t know if my mom’s in that group or not.

I know my dad isn’t.

Pamela Voorhees, she’s who I should write to, isn’t she? Or maybe Ellen Ripley. Put her in a dark hallway like this one in my head and she would lock and load, call her nerves a bitch, and tell them to get away from her.

I’m no Ripley.

Instead of locking and loading, what I do for about the thousandth time since the semester started is stumble on these stupid heels and lurch to the left, ramming my shoulder into a locker.

Just when you thought it was safe to walk like an adult.

Clear the beaches, mayor, Jade’s coming through again.

God.

Letha’s right about me: I’m always hiding in the video store, wearing all my movies like armor. Never mind that Proofrock’s video store’s been closed for three years now, is pretty much a memorial for all the kids who got skinned in there, are probably still haunting it.

That’s just playing on one screen, though.

Keep moving, Jade, keep moving.

On one of the other screens, though, are the two sleepless nights the weekend of the thirteenth, when Proofrock was in a panic over Jan Jansson going missing. But then word came in that his dad, who had split, had also rented a red Mustang convertible the day before. One fast enough to drive back from Nevada or whatever state he was hiding in, one alluring enough for his only son to want to take a ride in. So all the flyers were peeled off the windows of the bank, of Dot’s, of the drugstore, and a certain excon was finally able to sleep again.

They’ll find him, everybody is assuring themselves. He’s just with his dad, having an adventure—top down, hair in the wind, not a single drive-through window being missed.

Either that or he’s a kid-shaped bargaining chip in an escalating divorce.

There’s no blades looming, though, that’s the important thing. There’s no shadows lurking, no heavy breathing, no drunk shapes suddenly standing in the doorway at two o’clock in the stupid-ass morning.

I right myself from the locker I’ve crashed into—I think it was Lee Scanlon’s, once upon a time—blink my eyes fast like trying to get the lights to come back up in this hallway, but . . . okay, seriously now: Where in the living hell is everybody?

It’s Monday, not Friday, meaning no pep rally for football. Nobody pulled the fire alarm. It’s not senior skip day, and Banner hasn’t instituted some curfew to keep everyone safe—there’s no reason to. Ghostface isn’t out there slicing and dicing. Cinnamon Baker doesn’t live here anymore. There’s no once-in-a-century blizzard spooling up: been there, done that, we’re good for ninety-six more years, thanks.

A shooter drill, maybe? We are eight thousand feet up the mountain, meaning even the guns have guns, but . . . no.

There’s a lot wrong with Proofrock, but not that, anyway.

So far.

Could it be that seventh period just started? Is that what emptied the halls out? All the students dove into their classrooms and fought for seats because they really-really wanted to learn?

Dream on, slasher girl.

A fluorescent tube of light flickers in the ceiling a body length ahead, then sputters out again. It’s not for lack of money—Letha’s bankrolling the whole district, could put her name above the front doors if she wanted.

“Excuse me?” I say up to the light, holding my books to my chest.

The light buzzes back on, holds steady.

“Fuckin A . . .” I mutter to it, and keep moving, my clacking footsteps sounding all around me, and, passing a fire extinguisher I become one hundred percent certain that Rexall’s just caught me on candid camera “engaging in profanity on school grounds,” is going to turn it in to Principal Harrison, just moved up from Golding Elementary.

He’s already not fond of my full-sleeve tats. My hair’s okay in principle, I think—long now, to my waist, and silky as everliving shit—but it’s not all black, either.

C’mon.

And I don’t wear my spider bites or my bull ring or my eyebrow stud to school anymore. Though there may be a piercing or two that are none of a principal’s business.

Sharona says I’m still trying to armor up, can’t I see that?

I tell her back that she just likes the way I was before, which is sort of a line from Return of the Living Dead III, featuring the queen of all piercing junkies—she’s no slouch with the eyeliner, either.

Well, okay, maybe I don’t say it exactly like that. But I think the hell out of it.

What I also don’t say out loud: that you just slipped, My Sharona. That bit about armoring up is pure Letha, which means the two of you talk about me and my progress, which . . . isn’t exactly the key to get me to be forthcoming?

What I did say out loud in reply to that armor line, though? Sort of on accident, sort of not?

“Jealous much?”

Where Sharona went after her high school beauty queen days, after she won the big Blonder Than Thou contest? That adult daycare called college. Where I went, twice? That finishing school for criminals called the clink, the slam, the stir. That old greybar hotel waiting at the end of every road my kind slouches down.

If you don’t armor up in there, Sharona, you never get out.

But, like you, I’ve also geared up with books, thanks. They all had to be paperback, because hardcovers can brain a girl, or get sharpened to a one-use point, but they finally added up enough to get me a degree. It’s correspondence, sure, but it was enough for Letha to strong-arm the school district she now owns into . . . this.

It’s strictly trial basis, nobody expects it to actually last, but . . . I’m trying?

And the school’s not actually dim, I can see that now. That’s just my idiot eyes, dialing the hallway down to a tunnel. The kind with a nightmare boiler room way down at the end, rushing up all around me with the first blink.

I’m still in Tina’s bodybag, I mean.

In spite of the three cigarettes I just trainsmoked back by woodshop, lighting the next off the last, praying against all hope that the nicotine would open my capillaries up enough to keep this clench from happening in my chest, in my head.

Things do not happen, I say inside. Things are made to happen.

This from John F. Kennedy, in a book I had to read twice to get it to stick enough for the test.

What JFK’s saying is that I’m doing this to myself. I didn’t walk into another panic attack. It wasn’t lying in wait for me. No, I made it happen, by allowing the bad thoughts to spool up, loop me into their spin cycle of death, my hand stabbing up like on the VHS cover of Mortuary. Once your thinking starts swirling around that chrome grate of the shower drain, good luck stopping it without cutting yourself.

Which is another thing I don’t do anymore. Or, can’t start doing again, anyway.

I can still slice into this bodybag, though.

Not with a razor, but with something almost as sharp: pharmaceuticals. After checking to be sure I’m alone, I peel two warm tablets up from the elastic waistband of the boy shorts under my long black poodle skirt, crush them between the pads of my thumb and index finger, and snort them deep into my head fast, before I can think about what I’m doing.

My theory on mood stabilizers and beta blockers and the rest of the usual suspects I’ve cycled through is that it’s stupid they have to go all the way down to the stomach only to slowly percolate back up to the brain. So I do it more direct, save them some travel time, get more bang for my buck.

And, I can take four at once and still be mostly myself, as far as anybody knows, but I already took one on my cigarette break, so.

As for what they’re supposed to dial back, make less unmanageable? Oh, I don’t know. A yachtful of one-percenters who were also parents, and I think sort of actually maybe wanted to be good members of the community, in spite of their rich asses? A lakeful of people I’ve known since before I could walk, none of whose insides I ever expected to have to see, and swim through? A video store of kids who didn’t ask to be skinned for Christmas? My mom, standing up to the scarfaced predator about to attack me, even though it was hopeless, and years too late? Mr. Holmes, sinking under the surface of the water, his fingers finally slipping from mine in a way I know I’ll never forget? Sheriff Hardy, and the way he looked back at me and nodded once before stepping into the water with his daughter?

And so many more, among and between.

I like to think that each particle of every tablet I take is just enough to cover up the memory of one of those dead people, at least for an afternoon.

Meaning they swim back up at night, yeah. Surprise.

But that’s hours later.

This is now.

With the cold heat of these last two tablets sizzling through my mucous membranes, I have to reach out for the wall on the right side to keep steady until the post-nasal drip starts like the slowest pendulum, swinging back and forth so steadily that, if I let it, if I just exercise a little mental discipline, it can even me out, it can quiet the splashing, the screams, it can let me step between these gusts of blowing snow, into a little pocket of safety.

I push off the wall with my fingertips and it’s like standing in a canoe, not a hallway, and I know I can spill over into the deep dark water at any moment, but—this in Principal Harrison’s judgmental tone—I’m already late enough as-is, don’t have time to wallow in my feelings.

So I don’t.

Sharona would never understand, but the way I finally step ahead, out of this tattered bodybag, is that I age Freddy ahead fourteen years, until he’s the snarky prof at the front of that grand classroom in Urban Legend, teaching about the babysitter and the man upstairs, about Pop Rocks and soda.

He’s completely in control up there, isn’t he?

He is.

So am I, so am I.

At least until I hear footsteps running up behind me.

In Nancy’s nightmare of a daydream, the admonishment she receives is that there’s no running in the hallway.

But there is, isn’t there?

I turn, am suddenly in a different hallway—one from 1996: a Ghostface is coming fast down the hall, slaloming from side to side with pitch-perfect goofiness, doing boogedy-boogedy hands left and right.

At first I retract into myself, clutching my books tight. It’s the day before Halloween, and even if Halloween’s functionally illegal in Proofrock, still, the rules have to sort of be off, don’t they?

But you used to walk these halls too, Jade, imagining them Slaughter High.

And these footsteps coming at you, they aren’t from 1996.

This Ghostface wasn’t even born, then.

When he makes to blast past me all anonymous, I step forward, make a fast fist around the long tail of this pull-on mask. I know how these masks work, I mean. It’s like a nun’s wimple. Just, for slasher church.

This would-be Ghostface’s head whips back, his arms even more Muppet now, but when he falls to his knees, starts sliding and leaning back, that Munch of a pale face finally comes off with a harsh snap, the mask wrapping once around my wrist and then just hanging there.

“Dwight,” I say down to this junior on his knees.

He probably thinks it’s a Dewey reference, but I’m really calling him Brad Pitt from Cutting Class. Because that’s what he’s doing.

“Um, Trent, ma’am,” he stammers, trying to peel out of the glittery Father Death robe he’s now tangled in.

Like I don’t who he is: Trent Morrison, of the Morrisons who came here with Tobias Golding and Glen Henderson, to pan Indian Creek. This great-great-whatever-grandson of miners has made it through two massacres to get this far in his academic career. And that’s after his grandparents made it through the Fire of ’64 and Camp Blood. After his parents knew better than to ever get into a car with my dad, because he was bound to go cartwheeling off the road sooner or later, trashing his face forevermore.

“And what is this?” I ask, about the mask.