Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

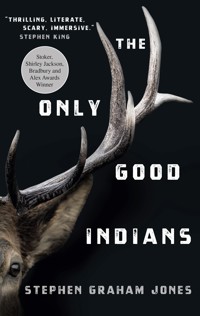

"Thrilling, literate, scary, immersive." —Stephen King The Stoker, Mark Twain American Voice in Literature, Bradbury, Locus and Alex Award-winning, NYT-bestselling gothic horror about cultural identity, the price of tradition and revenge for fans of Adam Nevill's The Ritual. Ricky, Gabe, Lewis and Cassidy are men bound to their heritage, bound by society, and trapped in the endless expanses of the landscape. Now, ten years after a fateful elk hunt, which remains a closely guarded secret between them, these men – and their children – must face a ferocious spirit that is coming for them, one at a time. A spirit which wears the faces of the ones they love, tearing a path into their homes, their families and their most sacred moments of faith. Ten years after that fateful hunt, these men are being stalked themselves. Soaked with a powerful gothic atmosphere, the endless expanses of the landscape press down on these men – and their children – as the ferocious spirit comes for them one at a time. The Only Good Indians, charts Nature's revenge on a lost generation that maybe never had a chance. Cleaved to their heritage, these parents, husbands, sons and Indians, men live on the fringes of a society that has rejected them, refusing to challenge their exile to limbo.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 448

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a review

Copyright

Dedication

Frontmatter

Williston, North Dakota

The House That Ran Red

Friday

Saturday

Monday

Tuesday

Wednesday

That Saturday

Friday

Saturday

Sunday

Monday

Tuesday

Still Tuesday

Three Dead, One Injured in Manhunt

Sweat Lodge Massacre

Friday

The Girl

Death Row

Sees Elk

Four The Old Way

Old Indian Tricks

The Sun Came Down

Shirts and Skins

Three Little Indians

Death, Too, for the Yellow Tail

Metal as Hell

This Is How You Learn To Break-Dance

Blackfeet Indian Stories

And Then There Was One

Mocassin Telegraph

It Came From The Rez

Saturday

Thanksgiving Classic

One Little Indian

Blood-Clot Boy

Where The Old Ones Go

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also Available from Titan Books

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

The Only Good Indians

Print edition ISBN: 9781789095296

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789095302

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.

144 Southwark Street, London, SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition: July 2020

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Copyright © 2020 Stephen Graham Jones. All rights reserved.

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

FOR

JIM KUHN

HE WAS A REAL HORROR FAN

This scene of terror is repeated all too often in elk country every season. Over the years, the hunters’ screams of anguish have rocked the timber.

—Don Laubach and Mark Henkel, Elk Talk

WILLISTON,NORTH DAKOTA

The headline for Richard Boss Ribs would be INDIAN MAN KILLED IN DISPUTE OUTSIDE BAR.

That’s one way to say it.

Ricky had hired on with a drilling crew over in North Dakota. Because he was the only Indian, he was Chief. Because he was new and probably temporary, he was always the one getting sent down to guide the chain. Each time he came back with all his fingers he would flash thumbs-up all around the platform to show how he was lucky, how none of this was ever going to touch him.

Ricky Boss Ribs.

He’d split from the reservation all at once, when his little brother Cheeto had overdosed in someone’s living room, the television, Ricky was told, tuned to that camera that just looks down on the IGA parking lot all the time. That was the part Ricky couldn’t stop cycling through his head: that’s the channel only the serious-old of the elders watched. It was just a running reminder how shit the reservation was, how boring, how nothing. And his little brother didn’t even watch normal television much, couldn’t sit still for it, would have been reading comic books if anything.

Instead of shuffling around the wake and standing out at the family plot up behind East Glacier, everybody parked on the logging road behind it so they’d have to come right up to the graves to turn their cars around, Ricky ran away to North Dakota. His plan was Minneapolis—he knew some cats there—but then halfway there the oil crew had been hiring, and said they liked Indians because of their built-in cold resistance. It meant they might not slip off in winter.

Ricky, sitting in the orange doghouse trailer for that interview, had nodded yeah, Blackfeet didn’t care about the cold, and no, he wouldn’t leave them shorthanded in the middle of a week. What he didn’t say was that you don’t get cold-resistant because your jackets suck, you just stop complaining about it after a while, because complaining doesn’t make you any warmer. He also didn’t say that, first paycheck, he was gone to Minneapolis, bye.

The foreman interviewing him had been thick and windburned and sort of blond, with a beard like a Brillo pad. When he’d reached across the table to shake Ricky’s hand and look him in the eye while he did it, the modern world had fallen away for a long blink and the two of them were standing in a canvas tent, the foreman in a cavalry jacket, and Ricky already had designs on that jacket’s brass buttons, wasn’t thinking at all of the paper on the table between them that he’d just made his mark on.

This had been happening more and more to him the last few months. Ever since hunting went bad last winter and right up through the interview to now, not even stopping for Cheeto dying on that couch.

Cheeto hadn’t been his born name, but he had freckles and orange hair, so it wasn’t a name he could shake, either.

Ricky wondered how the funeral had gone. He wondered if right now there was a big mulie nosing up to the chicken-wire fence around all these dead Indians. He wondered what that big mulie saw, really. If it was just waiting all of these two-leggers out.

Cheeto would have thought it was a pretty deer, Ricky figured. He had never been a kid to get up early with Ricky to be out in the trees when light broke. He hadn’t liked killing anything except beers, probably would have been vegetarian if that was an option on the rez. His orange hair put enough of a bull’s-eye on his back, though. Eating rabbit food would have just got more dumb Indians lining up to put him down.

But then he’d died on that couch anyway, not even from anybody else, just from himself, at which point Ricky figured he’d get out as well, screw it. Sure, he could be this crew’s chain monkey for a week or two. Yeah, he could sleep four to a doghouse with all these white boys, the wind rocking the trailer. No, he didn’t mind being Chief, though he knew that, had he been around back in the days of raiding and running down buffalo, he’d have been a grunt then as well. Whatever the bow-and-arrow version of a chain monkey was, that’d be Ricky Boss Ribs’s station.

When he was a kid there’d been a picture book in the library, about Heads-Smashed-In or whatever it was called—the buffalo jump, where the old-time Blackfeet ran herd after herd off the cliff. Ricky remembered that the boy selected to drape a calf robe over his shoulders and run out in front of all those buffalo, he’d been the one to win all the races the elders had put him and all the other kids in, and he’d been the one to climb all the trees the best, because you needed to be fast to run ahead of all those tons of meat, and you needed good hands to, at the last moment after sailing off the cliff, grab on to the rope the men had already left there, that would tuck you up under, safe.

What had it been like, sitting there while the buffalo flowed down through the air within arm’s reach, bellowing, their legs probably stiff because they didn’t know for sure when the ground was coming?

What had it felt like, bringing meat to the whole tribe?

They’d almost done it last Thanksgiving, him and Gabe and Lewis and Cass, they’d meant to, they were going to be those kinds of Indians for once, they had been going to show everybody in Browning that this is the way it’s done, but then the big wet snow had come in and everything had gone pretty much straight to hell, leaving Ricky out here in North Dakota like he didn’t know any better than to come in out of the cold.

Fuck it.

All he was going to hunt in Minneapolis was tacos, and a bed.

But, until then, this beer would work.

The bar was all roughnecks, wall-to-wall. No fights yet, but give it time. There was another Indian, Dakota probably, nursing a bottle in a corner by the pool tables. He’d acknowledged Ricky and Ricky had nodded back, but there was as much distance between the two of them as there was between Ricky and his crew.

More important, there was a blond waitress balancing a tray of empties between and among. Fifty sets of eyes were tracking her, easy. To Ricky she looked like the tall girl Lewis had run off to Great Falls with in July, but she’d probably already left his ass, meaning now Lewis was sitting in a bar down there just like this one, peeling the label off his beer just the same.

Ricky lifted his bottle in greeting, across all the miles.

Four beers and nine country songs later, he was standing in line for the urinal. Except the line was snaking all back down the hall already, and the last time he’d been in there there’d already been guys pissing in the trash can and the sink both. The air in there was gritty and yellow, almost crunched between Ricky’s teeth when he’d accidentally opened his mouth. It wasn’t any worse than the honeypots out at the rig, but out at the rig you could just unzip wherever, let fly.

Ricky backed out, drained his beer because cops love an Indian with a beer bottle in the great outdoors, and made to push his way out for a breath of fresh air, maybe a fence post in desperate need of watering.

At the exit the bouncer opened his meaty hand against Ricky’s chest, warned him about leaving. Something about the head count and the fire marshal.

Ricky looked past the open door to the clump of roughnecks and cowboys waiting to come in, their eyes flashing up to him but not asking for anything. It was the queue Ricky would have to mill around in to wait his turn to get back in. But it was starting to not really be his decision anymore, right? Inside of maybe ninety seconds, here, he was going to be peeing, so any way he could up the chances of being someplace where he could do that without making a mess of himself, well.

He could stand in a thirty-minute line to eyeball that blond waitress some more, sure. Ricky turned sideways to slip past the bouncer, nodding that he knew what he was doing, and already a roughneck was stepping forward to take his place.

There wasn’t even any time to stiff-leg it over beside the bar, by the steaming pile of bags the dumpsters were. Ricky just walked straight ahead, out into the sea of crew cab trucks parked more or less in rows, and on the way he unleashed almost before he could come to a stop, had to lean back from it because this was a serious fire-hose situation.

He closed his eyes from the purest pleasure he’d felt in weeks, and when he opened them, he had the feeling he wasn’t alone anymore.

He steeled himself.

Only stupid Indians brush past a bunch of hard-handed white dudes, each of them sure that seat you had in the bar, it should have, by right, been theirs. They’re cool with the Chief among them being the chain monkey, but when it comes down to who has an eyeline on the white woman, well, that’s another thing altogether, isn’t it?

Stupid, Ricky told himself. Stupid stupid stupid.

He looked ahead, to the hood he was going to hip-slide over, the bed of the truck he hoped wasn’t piled with ankle-breaking equipment, because that was his next step. A clump of white men can beat an Indian into the ground, yeah, no doubt about it, happens every weekend up here on the Hi-Line. But they have to catch his ass first.

And now that he was, by his figuring, about three fluid pounds lighter, and sobering up fast, no way was even the ex–running back of them going to hook a finger into Ricky’s shirt.

Ricky grinned a tight-lipped grin to himself and nodded for courage, dislodging all the rifles he couldn’t keep stacked up in his head, rifles that were actually behind the seat of his truck back at the site. When he’d left Browning he’d taken them all, even his uncles’ and granddad’s—they were all in the same closet by the front door—and then grabbed the gallon baggie of random shells, figuring some of them had to go to these guns.

The idea had been that he was going to need stake-money when he hit Minneapolis, and rifles turn into cash faster than just about anything. Except then he’d found work along the way. And he’d got to thinking about his uncles needing to fill their freezer for the winter.

Standing in the sprawling parking lot of the roughneck bar in North Dakota, Ricky promised to mail every one of those back. Would he have to pull the bolts, though, mail them in separate packages from the rifles, so the rifles wouldn’t really be rifles anymore?

Ricky didn’t know, but he did know that right now he wanted that pump .30-06 in his hands. To shoot if it came to that, but mostly just to swing around, the open end of the barrel leaving half-moons in cheeks and eyebrows and rib cages, the butt perfect for jaws.

He might be going down in this parking lot in a puddle of his own piss, but these grimy white boys were going to remember this Blackfeet, and think twice the next time they saw one of him walking into their bar.

If only Gabe were here. Gabe liked this kind of shit—playing cowboys and Indians in all the parking lots of the world. He’d do his stupid war whoop and just rush the hell in. It might as well have been a hundred and fifty years ago for him, every single day of his ridiculous life.

When you’re with him, though, with Gabe… Ricky narrowed his eyes, nodded to himself again for strength. To fake it anyway—to try to be like Gabe, here. When Ricky was with Gabe, he’d always want to give a whoop like that too, the kind that made it where, when he turned around to face these white boys, it’d feel like he was holding a tomahawk in his hand. It’d feel like his face was painted in harsh crumbly blacks and whites, maybe a single finger-wide line of red on the right side.

The years can just fall away, man.

“So,” Ricky said, his hands balled into fists, chest already heaving, and turned around to get this over with, his teeth clenched tight so that if he was turning around into a fist it wouldn’t rattle him too much.

But… no one?

“What the—?” Ricky said, cutting himself off because there was something, yeah.

A huge dark form, clambering over a pearly white, out-of-place 280Z.

Not a horse, either, like he’d knee-jerked into his head. Ricky had to smile. This was an elk, wasn’t it? A big meaty spike, too dumb to know this was where the people went, not the animals. It blew once through its nostrils and launched into the truck to its right, leaving the pretty sloped-down hood of that little Nissan taco’d up at the edges, stomped all down in the middle. But at least the car had been quiet about it. The truck the elk had slammed into was much more insulted, screaming its shrill alarm loud enough that the spike grabbed onto the ground with all four hooves. Instead of the twenty logical paths it could have taken away from this sound, it scrabbled up across the loud truck’s hood, fell off into the between space on the other side.

And now that drunk little elk was banging into another truck, and another.

All the alarms were going off, all the lights going back and forth.

“What is into you, man?” Ricky said to the spike, impressed.

The feeling didn’t last long. Now the spike was turned around, was barreling down an aisle between the cars, Ricky right in its path, its head down like a mature bull—

Ricky threw himself to the side, into another truck, setting off another alarm.

“You want some of me?” Ricky yelled to the elk, reaching over into the bed of a random truck. He came up with a jawless, oversized crescent wrench that would be a good enough deterrent, he figured. He hoped.

Never mind he was outweighed by a cool five hundred pounds.

Never mind that elk don’t do this.

When he heard the spike blow behind him he turned already swinging, crashing the crescent wrench’s round head into the side mirror of a tall Ford. The big Ford’s alarm screamed, flashed every light it had, and when Ricky turned around to shuffling hooves behind him, it wasn’t hooves this time, but boots.

All the roughnecks and cowboys waiting to get into the bar.

“He… he—” Ricky said, holding the wrench like a tire beater, every second truck in his immediate area flashing in pain, and showing the pounding they’d just taken. He saw it too, saw them seeing it: this Indian had got hisself mistreated in the bar, didn’t know who drove what, so he was taking it out on every truck in the parking lot.

Typical. Momentarily one of these white boys was going to say something about Ricky being off the reservation, and then what was supposed to happen could get proper-started.

Unless Ricky, say, wanted to maybe live.

He dropped the wrench into the slush, held his hand out, said, “No, no, you don’t understand—”

But they did.

When they stepped forward to put him down in time-honored fashion, Ricky turned, flopped half over the 280Z he hadn’t trashed, endured a bad moment when somebody’s reaching fingers were hooked into a belt loop, but he spun his hips hard, tore through, fell down and ahead, his hands to the ground for a few overbalanced steps. A beer bottle whipped by his head, shattered on a grille guard right in front of him, and he threw his hands up to keep his eyes safe, veered what he thought was around that truck but not enough—his hip caught the last upright of the guard, spun him around, into another truck, with another stupid alarm.

“Fuck you!” he yelled to the truck, to all the trucks, all the cowboys, just North Dakota and oil fields and America in general, and then, running hard down a lane between trucks, hitching himself ahead with more mirrors, two of them coming off in his hands, he felt a smile well up on his face, Gabe’s smile.

This is what it feels like, then.

“Yes!” Ricky screamed, the rush of adrenaline and fear sloshing up behind his eyes, crashing over his every thought. He turned around and ran backward so he could point with both hands at the roughnecks. Four steps into this big important gesture he fell out into open space, kind of like a turnrow in a plowed field, caught his left boot heel on a rock or frozen clump of bullshit grass, went sprawling.

Behind him he could see dark shapes vaulting over whole truck beds, their cowboy hats lifting with them, not coming down, just becoming part of the night.

“White boys can move…” he said to himself, less certain of all this, and pivoted, rose, was moving again, too.

When the footfalls and boot slaps were too close, close enough he couldn’t handle it, knew this was it, Ricky grabbed a fiberglass dually fender, used it to swing himself a sharp and sudden ninety degrees, into what would have been the truck’s long side, what should have been its side, but he was sliding now, he was going under, leading with the slick heels of his work boots.

This was the kind of getting away he’d learned at twelve years old, when he could slither and snake.

The truck was just tall enough for him to slide under, through the muck, his momentum carrying him halfway across. To get across the rest of the truck’s width, he reached up for a handhold, the skin of his palm and the underside of his fingers immediately smoking from the three-inch exhaust pipe.

Ricky yelped but kept moving, came up on the other side of the truck fast enough that he slammed into a beater that didn’t have an alarm. Two truck lengths ahead, the dark shapes were pulling their best one-eighty, casting left and right for the Indian.

Duck, Ricky told himself, and disappeared, ran at a crouch that felt military, like he was in a trench, like shells were flying. And they might as well be.

“There he is!” a roughneck bellowed, and his voice was far enough off that Ricky knew he was wrong, that they were about to pile onto somebody else for ten or twenty seconds, until they realized this was no Indian.

Ten trucks between him and them finally, Ricky stood to his full height to make sure it wasn’t that Dakota dude catching the heat.

“I’m right here,” Ricky said to the roughnecks, not really loud enough, then turned, stepped through the last line of trucks, out into the ditch of the narrow ribbon of blacktop that had brought him here, that ran between the bar’s parking lot and miles and miles of frozen grasslands.

So it was going to be a walking night, then. A hiding from every pair of headlights night. A cold night. Good thing I’m Indian, he told himself, sucking in to get the zipper on his jacket started. Cold doesn’t matter to Indians, does it?

He snorted a laugh, flipped the whole bar off without turning around, just an over-the-shoulder thing with his smoldering hand, then stepped up onto the faded asphalt right as a bottle burst beside his boot.

He flinched, drew in, looked behind him to the mass of shadows that were just arms and legs and crew cuts now, moving over the trucks.

They’d seen him, made his Indian silhouette out against all this pale frozen grass.

He hissed a pissed-off blast of air through his teeth, shook his head once side to side, and straight-legged it across the asphalt to see how committed they might be. They want an Indian bad enough tonight to run out into the open prairie in November, or would it be enough just to run him off?

Instead of trusting the gravel and ice of the opposite shoulder, Ricky took it at a slide, let his momentum stand him up once his boot heels caught grass, then transferred all that into a leaning-forward run that was going to have been a fall even if he hadn’t caught the top strand of fence in the gut. He flipped over easy as anything, the strand giving up its staples halfway through, just to be sure his face planted all the way into the crunchy grass on the other side.

Ricky rolled over, his face to the wash of stars spread against all the blackness, and considered that he maybe should have just stayed home, gone to Cheeto’s funeral, he maybe shouldn’t have stolen his family’s guns. He maybe should have never even left the rez at all.

He was right.

When he stood, there was a sea of green eyes staring back at him from right there, where there was just supposed to be frozen grass and distance.

It was a great herd of elk, waiting, blocking him in, and there was a great herd pressing in behind him, too, a herd of men already on the blacktop themselves, their voices rising, hands balled into fists, eyes flashing white.

INDIAN MAN KILLED IN DISPUTE OUTSIDE BAR.

That’s one way to say it.

FRIDAY

Lewis is standing in the vaulted living room of his and Peta’s new rent house, staring straight up at the spotlight over the mantel, daring it to flicker on now that he’s looking at it.

So far it only comes on with its thready glow at completely random times. Maybe in relation to some arcane and unlikely combination of light switches in the house, or maybe from the iron being plugged into a kitchen socket while the clock upstairs isn’t—or is?—plugged in. And don’t even get him started on all the possibilities between the garage door and the freezer and the floodlights aimed down at the driveway.

It’s a mystery, is what it is. But—more important—it’s a mystery he’s going to solve as a surprise for Peta, and in the time it takes her to drive down to the grocery store and back for dinner. Outside, Harley, Lewis’s malamutant, is barking steady and pitiful from being tied to the laundry line, but the barks are already getting hoarse. He’ll give it up soon enough, Lewis knows. Unhooking his collar now would be the dog training him, instead of the other way around. Not that Harley’s young enough to be trained anymore, but not like Lewis is, either. Really, Lewis imagines, he deserves some big Indian award for having made it to thirty-six without pulling into the drive-through for a burger and fries, easing away with diabetes and high blood pressure and leukemia. And he gets the rest of the trophies for having avoided all the car crashes and jail time and alcoholism on his cultural dance card. Or maybe the reward for lucking through all that—meth too, he guesses—is having been married ten years now to Peta, who doesn’t have to put up with motorcycle parts soaking in the sink, with the drips of Wolf-brand chili he always leaves between the coffee table and the couch, with the tribal junk he always tries to sneak up onto the walls of their next house.

Like he’s been doing for years, he imagines the headline on the Glacier Reporter back home: FORMER BASKETBALL STAR CAN’T EVEN HANG GRADUATION BLANKET IN OWN HOME. Never mind that it’s not because Peta draws the line at full-sized blankets, but more because he used it for padding around a free dishwasher he was bringing home a couple of years ago, and the dishwasher tumped over in the bed of the truck on the very last turn, spilled clotty rancid gunk directly into Hudson’s Bay.

Also never mind that he wasn’t exactly a basketball star, half a lifetime ago.

It’s not like anybody but him reads this mental newspaper. And tomorrow’s headline?

THE INDIAN WHO CLIMBED TOO HIGH. Full story on 12b.

Which is to say: that spotlight in the ceiling’s not coming down to him, so he’s going to have to go up to it.

Lewis finds the fourteen-foot aluminum ladder under boxes in the garage, Three Stooges it into the backyard, scrapes it through the sliding glass door he’s promised to figure out a way to lock, and sets it up under this stupid little spotlight, the one that all it’ll do if it ever works is shine straight down on the apron of bricks in front of the fireplace that Peta says is a “hearth.”

White girls know the names of everything.

It’s kind of a joke between them, since it’s how they started out. Twenty-four-year-old Peta had been sitting at a picnic table over beside the big lodge in East Glacier, and twenty-six-year-old Lewis had finally got caught mowing the same strip of grass over and over, trying to see what she was sketching.

“So you’re, what, scalping it?” she’d called out to him, full-on loud enough.

“Um,” Lewis had said back, letting the push mower die down.

She explained it wasn’t some big insult, it was just the term for cutting a lawn down low like he was doing. Lewis sat down opposite her, asked was she a backpacker or a summer girl or what, and she’d liked his hair (it was long then), he’d wanted to see all her tattoos (she was already maxed out), and within a couple weeks they were an every night kind of thing in her tent, and on the bench seat of Lewis’s truck, and pretty much all over his cousin’s living room, at least until Lewis told her he was busting out, leaving the reservation, screw this place.

How he knew Peta was a real girl was that she didn’t look around and say, but it’s so pretty or how can you or—worst—but this is your land. She took it more like a dare, Lewis thought at the time, and inside of three weeks they were a nighttime and a daytime kind of thing, living in her aunt’s basement down here in Great Falls, making a go of it. One that’s still not over somehow, maybe because of good surprises like fixing the unfixable light.

Lewis spiders up the shaky ladder and immediately has to jump it over about ten inches, to keep from getting whapped in the face by the fan hanging down on its four-foot brass pole. If he’d checked The Book of Common Sense for stunts like this—if he even knew what shelf that particular volume might be on—he imagines page one would say that before going up the ladder, consider turning off all spinny things that can break your fool nose.

Still, once he’s up higher than the fan, when he can feel the tips of the blades trying to kiss his hipbone through his jeans, his fingertips to the slanted ceiling to keep steady, he does what anybody would: looks down through this midair whirlpool, each blade slicing through the same part of the room for so long now that... that...

That they’ve carved into something?

Not just the past, but a past Lewis recognizes.

Lying on her side through the blurry clock hands of the fan is a young cow elk. Lewis can tell she’s young just from her body size—lack of filled-outness, really, and kind of just a general lankiness, a gangliness. Were he to climb down and still be able to see her with his feet on the floor, he knows that if he dug around in her mouth with a knife, there wouldn’t be any ivory. That’s how young she still is.

Because she’s dead, too, she wouldn’t care about the knife in her gums.

And Lewis knows for sure she’s dead. He knows because, ten years ago, he was the one who made her that way. Her hide is even still in the freezer in the garage, to make gloves from if Peta ever gets her tanning operation going again. The only real difference between the living room and the last time he saw this elk is that, ten years ago, she was on blood-misted snow. Now she’s on a beige, kind of dingy carpet.

Lewis leans over to get a different angle down through the fan, see her hindquarters, if that first gunshot is still there, but then he stops, makes himself come back to where he was.

Her yellow right eye… was it open before?

When it blinks Lewis lets out a little yip, completely involuntary, and flinches back, lets go of the ladder to wheel his arms for balance, and knows in that instant of weightlessness that this is it, that he’s already used all his get-out-of-the-graveyard-free coupons, that this time he’s going down, that the cornermost brick of the “hearth” is already pointing up more than usual, to crack into the back of his head.

The ladder tilts the opposite way, like it doesn’t want to be involved in anything this ugly, and all of this is in the slowest possible motion for Lewis, his head snapping as many pictures as it can on the way down, like they can stack up under him, break his fall.

One of those snapshots is Peta, standing at the light switch, a bag of groceries in her left arm.

Because she’s Peta, too, onetime college pole vaulter, high school triple-jump state champion, compulsive sprinter even now when she can make time, because she’s Peta, who’s never known a single moment of indecision in her whole life, in the next snapshot she’s already dropping that bag of groceries that was going to be dinner, and she’s somehow shriking across the living room not really to catch Lewis, that wouldn’t do any good, but to slam him hard with her shoulder on his way down, direct him away from this certain death he’s falling onto.

Her running tackle crashes him into the wall with enough force to shake the window in its frame, enough force to send the ceiling fan wobbling on its long pole, and an instant later she’s on her knees, her fingertips tracing Lewis’s face, his collarbones, and then she’s screaming that he’s stupid, he’s so, so stupid, she can’t lose him, he’s got to be more careful, he’s got to start caring about himself, he’s got to start making better decisions, please please please.

At the end she’s hitting him in the chest with the sides of her fists, real hits that really hurt. Lewis pulls her to him and she’s crying now, her heart beating hard enough for her and Lewis both.

Raining down over the two of them now—Lewis almost smiles, seeing it—is the finest washed-out brown-grey dust from the fan, which Lewis must have hit with his hand on the way down. The dust is like ash, is like confectioner’s sugar if confectioner’s sugar were made from rubbed-off human skin. It dissolves against Lewis’s lips, disappears against the wet of his open eyes.

And there are no elk in the living room with them, though he cranes his head up over Peta to be sure.

There are no elk because that elk couldn’t have been here, he tells himself. Not this far from the reservation.

It was just his guilty mind, slipping back when he wasn’t paying enough attention.

“Hey, look,” he says to the top of Peta’s blond head.

She rouses slowly, turns to the side to follow where he’s meaning.

The ceiling of the living room. That spotlight.

It’s flickering yellow.

SATURDAY

On break at work—he’s supposed to be training the new girl, Shaney—Lewis calls Cass.

“Long time, no hear,” Cass says, his reservation accent a singsong kind of pure Lewis hasn’t heard for he doesn’t know how long. In response, Lewis’s voice, smoothed down flat from only ever talking to white people, rises like it never even left. It feels unfamiliar in his mouth, in his ears, and he wonders if he’s faking it somehow.

“Had to call your dad to get your number,” he says to Cass.

“What happens when you move away for ten years, yeah?”

Lewis shifts the phone to his other ear.

“So what’s going?” Cass asks. “Not calling from jail, are you? Post office finally figure out you’re Indian, what?”

“Pretty sure they know,” Lewis says. “It’s the first checkbox.”

“Then it’s her,” Cass says with what sounds like a grin. “She finally figured out you’re Indian, enit?”

What Cass and Gabe and Ricky had told him when he was running off with Peta was that he should get his return address tattooed on his forearm, so he could get his ass shipped back home when she got tired of playing Dr. Quinn and the Red Man.

“You wish she’d figure it out,” Lewis tells Cass on the phone, turning to be sure Shaney, his shadow for the day, isn’t standing in the break room doorway soaking all this in. “She even lets me hang my Indian junk on all the walls.”

“Like Indian-Indian,” Cass says, “or Indian just because an Indian owns it?”

“I called to ask a question,” Lewis says, quieter, closer.

Of Gabe and Ricky and Cass, Cass was always the one he could dial down to “serious” easiest. Like the real him, the real and actual person, wasn’t buried as deep under attitude and jokes and bluster as it was with Ricky and Gabe.

Not that Ricky, being dead, really has a telephone number anymore.

Shit, Lewis says inside.

He hasn’t thought about Ricky for nearly ten years now. Not since he heard.

The headline flashes in his head: INDIAN MAN HAS NO ROOTS, THINKS HE’S STILL INDIAN IF HE TALKS LIKE AN INDIAN.

Lewis breathes in, covers the handset to breathe out, so Cass won’t hear it across all these miles.

“Those elk,” he says.

After a long enough time that he can be sure Cass knows exactly the elk he’s talking about, Cass says, “Yeah?”

“Do you ever…” Lewis says, still unsure how to say it, even though he ran it through his head all last night and all the way in to work. “Do you ever, you know, think about them?”

“Am I still pissed off about them?” Cass fires right back. “I see Denny on fire on the side of the road, you think I stop to piss on him?”

Denny Pease, the game warden.

“He’s still on the job?” Lewis asks.

“Running the office now,” Cass says.

“Still a hard-ass?”

“He fights for Bambi,” Cass says, like that’s still in circulation all this time later. It was what they all used to say about the game crew: anytime Man was in the forest, all the wardens’ ears perked up, and their citation books flapped open.

“Why you asking about him?” Cass says.

“Not him,” Lewis says. “Just thinking, I guess. Ten-year anniversary, I don’t know.”

“Ten years in, what, a week?” Cass says.

“Two,” Lewis says, shrugging like he doesn’t mean to have it all figured down this precise. “It was the last Saturday before Thanksgiving, wasn’t it?”

“Yeah, yeah,” Cass says. “Last day of the season…”

Lewis winces without any sound, closes his eyes tight. The way Cass dragged that last part out all suggestive, it’s the same as reminding Lewis it wasn’t the last day of the season. Just, the last day they’d been able to all get together to hunt.

But it was also, as it turned out, the last day of their season in a different way, he guesses.

He shakes his head three times like trying to clear it, and tells himself again that no way did he see that young elk on the floor of his living room.

She’s dead, she’s gone.

To pay for her, even, the day before he left with Peta, he’d taken all the packaged-up meat of her and gone door-to-door down Death Row, giving it to the elders. Because she’d come from the elders’ section—the good country saved back for them up by Duck Lake, so they could fill their freezers from the field instead of the IGA—because she’d come from there, it was all full circle and Indian, hand-delivering the meat to their doors. Never mind that Lewis couldn’t find any of his meat stamps, had to use Ricky’s little sister’s stamps. So, instead of STEAK or GROUND or ROAST, all the butcher paper the young elk was wrapped in had a black raccoon handprint on it, because that was the only one she had that wasn’t a flower or a rainbow or a heart.

But no way could that elk be coming up from thirty stew pots all this time later, walking a hundred and twenty miles south to haunt Lewis. First because elk don’t do that, but second because, in the end, her meat had got where it was meant to get, he hadn’t even done anything wrong. Not really.

“Gotta go, man,” he tells Cass. “My boss.”

“It’s Saturday,” Cass says back.

“Rain nor sleet nor weekends,” Lewis says back, and hangs up more abruptly than he means, holds the phone on its cradle for a full half minute before lifting it back.

He dials in the number Cass’s dad gave him for Gabe. It’s Gabe’s dad’s number, actually, but Cass’s dad had looked out the window, said he could see Gabe’s truck over there right now.

“Tippy’s Tacos,” Gabe says after the second ring. It’s how he always answers, wherever he is, whoever’s phone. There was never a place called that on the reservation, as far as Lewis knows.

“Two with venison,” Lewis answers back.

“Ah, Indian tacos…” Gabe says, playing along.

“And two beers,” Lewis adds.

“You must be Navajo,” Gabe says right back, “maybe a fish tribe. If you were Blackfeet, you’d want a six with that.”

“I’ve known some Navajo can flat put it away,” Lewis says, a deviation from the usual routine, like bringing it down, breaking it. For maybe five seconds Gabe doesn’t say anything, then, “Lewdog?”

“First try,” Lewis says, his face warming just to be known.

“You in jail?” Gabe asks.

“Still a comedian,” Lewis tells him.

“Among other things,” Gabe says back, then, probably to his dad, “It’s Lewis, remember him, old man?”

Lewis doesn’t hear the reply, but does hear a basketball game cranked up high enough to be blasting through the whole house.

“So what’s up?” Gabe asks when he’s back. “Need bus fare home, what? If so, I can hook you up with somebody. Little light at the moment myself.”

“Still hunting?”

“That’d be under the ‘Among Other Things’ category, wouldn’t it?” Gabe says.

Of course he’s still hunting. Denny’d have to work 24/7 to write up even half of what Gabriel Cross Guns poaches on a weekly basis, and the rangers over in Glacier would have to work even harder to find his tracks, going back and forth across the Park line, the return prints a couple hundred pounds deeper than the ones sneaking in.

“How’s Denorah?” Lewis says, because that’s where you start after this long.

Denorah’s Gabe’s daughter by Trina, Trina Trigo, has to be twelve or thirteen by now—she was walking around already when Lewis left, anyway, he’s pretty sure of that.

“My finals girl, you mean?” Gabe says, finally all the way into this call, it feels like.

“Your what?” Lewis asks all the same.

“You remember Whiteboy Curtis from Havre?” Gabe asks. Lewis can’t dredge up Whiteboy’s actual last name—something German?—but yeah, he remembers: Curtis, the baller, this naturally gifted farm kid who was born for the court. He didn’t see it all with his eyes, he felt the game through his feet like radar, and didn’t even have to think to know which way to cut. And he had that basketball on a string, one hundred percent. Only thing kept him from going college was his height, and that he insisted he was a power forward, not a stop-and-pop sharpshooter. At high school height, sure, someone just six-two could crash in, dominate as a power forward. And he had some jumps, too, could rise up and flush it—only in pregame, with a lot of setup, but still. In the end, though, he wasn’t built like Karl Malone, but like John Stockton. Just, he couldn’t accept that, had the idea he could go inside at the next level, bang his way through the bigs, not be a pinball bouncing off them. Insisting he was that power forward, he’d lost so many teeth he looked like a hockey player, last Lewis had heard. And the concussions weren’t exactly doing anything good for his short-term memory. It would have been better for the rest of his life if he’d never figured he could play.

Still?

“He had that jump shot,” Lewis says, seeing it again, the way Whiteboy Curtis would just hang and hang, wait for everyone else to sink back down before releasing the ball so perfect, his eyes laser-guiding it up and up, and, finally, in.

“Denorah’s like that,” Gabe whispers, like the best secret ever. “Just, better, man. Serious. Browning’s never seen nothing like her.”

“I should come watch her play,” Lewis says.

“You should,” Gabe says. “Just, don’t tell Trina I told you to come. Maybe don’t even talk to her. If she looks at you? She does, maybe cut your hair, change your name, jump on a ship.”

“She still out for blood?”

“Woman can hold a grudge,” Gabe says. “Got to give her that.”

“For no reason, of course,” Lewis says, leaning back on the usual lines again.

“So to what do I owe this call, Mr. Postman?” Gabe says then, being all fake formal. “I forget to put a stamp on something, what?”

“Just been a while,” Lewis says.

“It was a while eight, nine years ago,” Gabe says. “You’re talking to me, man.”

A lump forms in Lewis’s throat. He tilts his face back, closes his eyes.

“I was just remembering when Denny—”

“Fucked us permanent?” Gabe cuts in. “Yeah, something about that maybe rings a bell or two…”

“You ever been back there by Duck Lake again?” Lewis asks.

“You have to have an old-timer with you,” Gabe says. “You know that, man. How long you been gone again?”

“I mean where it happened,” Lewis says. “That drop-off place.”

“That place, that place, yeah,” Gabe says, driving a nail into Lewis’s heart. “It’s haunted, man, didn’t you know? Elk don’t go there anymore, even. I bet they even tell stories around the elk campfires, right? About what went down that day? Shit, we’re legends to them, man. The four boogeymen—the four butchers of Duck Lake.”

“Three,” Lewis says. “The three boogeymen.”

“They don’t know that,” Gabe says.

“But you really think they might remember?” Lewis asks, just hanging it all out there at last.

“Remember?” Gabe says, the smile one hundred percent there in his voice. “They’re fucking elk, man. They don’t really have campfires.”

“And we killed them all anyway, yeah?” Lewis says, blinking the heat from his eyes. looking around again for Shaney.

“What’s this about?” Gabe says then. “You still missing that crappy knife, what?”

Lewis has to strain to dial back to what Gabe’s saying: that trading post knife he’d bought, with the three or four interchangeable blades, one of them a weak little saw, for the breastbone and pelvis.

“That knife was a piece of shit,” Lewis says. “If you find it, lose it again fast, yeah?”

“Will do,” Gabe says, his voice far from the phone for a moment, basketball pouring into his end of the line. “Hey, we’re watching a—”

“I got to get gone, too,” Lewis says. “Nice hearing your dumb-ass voice again, though.”

“Shit, I should charge by the minute,” Gabe says, and ten, twenty seconds later the line’s dead again, and Lewis is standing there with his shoulder against the wall, tapping the handset into his forehead like a drumstick.

“Should I be taking notes, Blackfeet?” Shaney asks from the doorway.

Lewis hangs the phone up.

Shaney’s Crow, so calling him “Blackfeet” is this running joke, their tribes being longtime enemies.

“Something Peta said last night,” Lewis lies, always trying to be sure to remind Shaney about his wife, and then say something about her again, just to be sure. Not because he’s the ladies’ man of the USPS—there isn’t one—but because him and Shaney are the only two Indians at this station, and for the last week, ever since Shaney passed the background check and hired on, everybody’s been doing that thing they do with armchairs or end tables when they match: trying to push him and her together over in the corner, leave them there to be this perfect set.

“Something your wife said?” Shaney asks, Lewis sliding past her, leading them back to the big sorting machine. He flicks it on to continue this lesson.

“We’ve got this crap light in the living room,” he tells her. “Won’t come on when it’s supposed to. She thinks it might be a short in the wall. Was calling a guy I know who does electrician stuff on the side.”

“On the side…” Shaney repeats, and nudges an envelope this way into the sorting machine instead of that way.

Lewis tracks that fast piece of mail up into the belly of the beast and shakes his head with wonder when nothing catches, nothing crumples.

Shaney grins a mischievous grin, bites her lower lip in at the end of it.

“Next time,” she says, and hip-checks Lewis.

He rolls with it, doesn’t push back, is miles and years away.

MONDAY

Duckwalking backward on his stripped-down, double-throaty Road King that’s about to find its lope, Lewis clocks Jerry already at the edge of the post office’s parking lot, hanging his loose right hand down by the rear wheel of his custom Springer, his index and middle fingers waggling in an upside-down peace sign before they curl up into his fast fist. Lewis has no idea what it means, never rode with a real and actual gang like Jerry did in his Easy Rider youth, but it must mean something like this way or all clear or smoke ‘em if you got ‘em, because Eldon and Silas throttle in right behind him, leaving Lewis to watch the back door like always, even though where they’re headed is to Lewis’s new place way the hell over on 13th.

Pecking order’s pecking order, though, and Lewis, even though this is his fifth year slinging mail, is still the new guy. Being last, though, that means that when Shaney comes running out the side door, Lewis’s bitch seat is what she jumps onto, barely making it.

Her hands fall perfect to his hips, her front to his back, and very much right there.

“Hello?” he says, throttled down and wobbling.

“I want to see too,” she says, shaking her head and loosening her hair.

Yeah, this is exactly what Peta needs to clock pulling into the driveway.

Still, Lewis grabs the next gear, falls in line, having to goose it to stay with.

Why they’re all going to his place is because Harley, at nearly ten years old, has taken to jumping the six-foot fence like a young dog, a fact Eldon says he’ll only believe when he sees it. So, he’s going to see it. They all are, including, now, Shaney.

Third in line is Silas, on his rattletrap scrambler that’s not good past fifty, but gets kind of fun at seventy-five, if near-death experiences are your thing. Eldon, snapping at Jerry’s heels, is on his slammed bobber, which he can only swing because he lives close to the post office, can walk in if the weather’s bad, so doesn’t need to keep and insure a truck or a car. Of the four of them he’s the only one not married, too, which frees up some funds, for sure. Jerry tells him to just wait, though, it’ll happen—“They’ll drop sooner or later,” haw haw haw. At fifty-three, Jerry’s the oldest of them, and comes complete with the silver handlebar stache, freckled-bald head, ratty ponytail, and icy blue eyes.

Silas is pretty much mute, and might even have some Indian in him somewhere, Lewis thinks. Not enough to have been Chief before Lewis earned that title, but… maybe as much Indian blood as Elvis had, however much that is? Like, enough to fill up a pair of blue suede shoes? Eldon claims to be Greek and Italian both, which is maybe a joke Lewis doesn’t quite get. Jerry doesn’t claim to be anything other than in constant need of another beer.

It’s good to have found them, after losing Gabe and Cass and Ricky. Well, after having left them.

No headlines about this. It’s just the same old news as ever.

The five o’clock traffic they slip past on River all cranes a bit to keep Shaney in view ten or twenty feet longer. Meaning her button-up flannel’s probably untucked and flapping, threatening to come off altogether.

Great.

Wonderful.

Lewis shouldn’t have said anything about Harley, he knows. It would be better just to be headed home alone, to maybe sink a few free throws in the driveway before Peta’s back. But—Harley, right? He’s not just not-young, he’s actually pretty damn old for a dog his size, has been hit twice on the road, one of those by a dump truck, and he’s been shot once, in the hip. And that’s just what Lewis knows about. There’ve been snakebites and porcupines and kids with pellet guns and all the usual dog fighting that any dog’s going to get up to. No way should Harley be able to clear that fence.

No way should he even have a reason to try. Still, four times now Lewis has found him out in the road, and Peta’s found him twice.

He must be jumping, maybe scrabbling a bit to get all the way over.

And Lewis should have kept it to himself.

Except?

Thinking and thinking about the young elk who couldn’t have been on his living room floor, Harley barking it up outside, Lewis had finally made what felt like a connection between the two. Could Harley have been barking at her, at the elk? Can he see her without a spinning fan? Has she been there all along, these past ten years?

Worse, if Harley can sense her, then is that what’s been driving him over the fence? Maybe it’s not about getting